The Exposed Unmentionables

The question most frequently asked of me is, “Which singer did you enjoy working with the most?” I have difficulty answering, as there were so many greats. The second most-asked question is, “Which singer did you enjoy working with the least?” This I have no trouble answering, though the very thought instantly causes a migraine and barely controllable shudders. It pains me even to type the answer, but here it is: Franco Bonisolli.

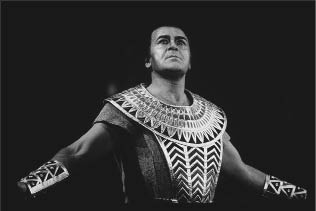

Let me start by saying that I liked Franco quite a bit — at first. When he was coming up he was a fine lyric tenor, and I delighted in directing him in lighter roles, like Alfredo in La Traviata, Ernesto in Don Pasquale, and the title role of Faust. He was also tall, lithe, and handsome — the very picture of the ardent young lover he often portrayed. In those days he seemed poised to follow in the footsteps of Alfredo Kraus, and with a little prudence he probably could have done just that. But something happened. Instead of being content with his natural vocal endowment, he insisted on pushing himself into bigger repertoire. Apparently, size mattered to Franco. The more he pushed, the crazier he got. Even his appearance changed. He bulked up a bit and his face got harder and more chiselled. It was like he had turned from Jekyll to Hyde. Franco had always been proud of his looks, but with his transformation he became insufferable. I never met anyone — male or female — who was more vain. I’m convinced that Franco’s mania was an acute case of Domingo-itis: he thought he could have Plácido’s glorious career by singing the same repertoire, but it simply wasn’t suited to his voice. Franco even knew it, though it didn’t seem to bother him too much. He once told me, “Domingo’s voice may be better than mine, but my legs are more beautiful.” Not for nothing did he earn the nickname Il Pazzo (The Madman). To borrow a quote from Anna Russell, “He had resonance where his brain ought to have been.”

Mugging to the audience is considered bad form in the theatre world, but Franco held it as something of a virtue — maybe even an art. During one performance of Il Trovatore at the Vienna Staatsoper he held the climactic high note of “Di quella pira” for so long that the curtain actually came down on him while he was still singing. That didn’t trouble Franco: at the last second he dove under the curtain and continued to hold the note, milking the applause for all it was worth. Plenty of people loved his antics — I think they saw his behavior as a kind of joke — but professional musicians winced. A few years later at an orchestra rehearsal of Aida at San Francisco Opera, Franco so egregiously indulged his habit of holding high notes that his co-star, Leontyne Price, walked offstage. “Ciao, Leontyne,” Franco called after her.

“Ciao my ass,” Leontyne yelled back. She spoke for all of us.

Add to this his legendary temper. He once appeared as Calàf in Turandot at the Verona Arena, and the tradition there is that Calàf repeats his major aria “Nessun dorma.” Before the performance Franco told conductor Anton Guadagno that he wasn’t feeling up to it, and they agreed to omit the repeat. However, during the performance Franco changed his mind and decided he wanted to do it after all. Obviously there was no way Guadagno could have known this, and so he went on as previously arranged. Franco couldn’t have been more offended if Guadagno had insulted the memory of his saintly mother. After the performance Franco burst into Guadagno’s dressing room and screamed at him mercilessly. The maestro was of diminutive stature and Franco easily towered over him. Adding injury to insult, Franco grabbed the cowering Guadagno by his coat, shook him, hung him on a hook in the dressing room, and stomped out. The maestro hung there until his cries attracted the attention of passersby.

Franco Bonisolli in Aida, 1984.

Photo by Ron Scherl.

Il Pazzo was in fine form in 1971 when I worked with him on my production of Manon, filmed at the Geneva Grand Theatre for French television. At the outset Franco made it clear that he had a serious problem, something that could prevent him from going on at all. A difference of artistic opinion? No. A feud with a castmate? No. The problem: his costume pants were not tight enough. And, apparently, it was not a problem that was easily fixed. Over and over he would try on the offending garment, only to let out a Grecian cry of “Tighter! Tighter!” The costumers worked overtime to make the pants ever more snug, but still Franco wasn’t satisfied. When his cries subsided I figured the matter was settled. It turns out that he had resorted to taking matters into his own hands. As we shot the dramatic last scene, which is set on the desolate road to Le Havre, I noticed that he didn’t look quite right. He’s supposed to be dishevelled and desperate but Franco’s look could only be described as indecent. The camera zoomed in to reveal that he had abandoned his costume pants altogether in favour of a pair of ballet tights — probably one size too small, and flesh-coloured to boot. As he wore nothing underneath, little was left to the imagination. We halted filming and I rushed to the stage. “Franco, your legs are fabulous,” I said, “But you shouldn’t be so proud of the rest.” He grumbled, but poured himself into his costume pants and we resumed shooting.

There was a darker side to his shenanigans. During that same filming, Franco kept delaying the difficult Saint-Sulpice scene. We jumped around, filming every other bit of the opera, with Franco offering one excuse after another: it was too late, it was too early, he was tired, the wind was blowing from the wrong direction. Finally, with nothing left to film, Franco looked me straight in the eye and said he couldn’t film Saint-Sulpice at all unless he got an additional 150,000 francs, which translated into roughly $30,000 at the time. We couldn’t simply omit the scene; with the aria “Ah! Fuyez, douce image” and the duet “N’est-ce plus ma main?” it is arguably the best part of the whole opera. The producers were over a barrel. They gave in to Franco, but told him he would never again appear on French television. He never did.

What an awful character. Still, in an odd way I do owe Franco for one thing: once you’ve worked with him, you’re ready for anybody.