An Offer I Couldn't Refuse

Comic operas are often described as confections, and in this regard Donizetti’s The Daughter of the Regiment is nothing less than a soufflé. As with its edible counterpart, the required ingredients include sweetness, a gentle touch, and a dollop of froth. There is no room in the recipe for concrete shoes, hit jobs, or Tommy guns in violin cases. Alas, I can’t help but associate mobster clichés with this lightest of light-hearted operas. There is a reason.

For many years soprano Beverly Sills reigned as America’s very own diva. Down-to-earth, smart, and vivacious, she fit the bill perfectly. Plus, she was one of the first opera singers to build a major career at home rather than in Europe. Through appearances on television programs, such as The Tonight Show with Johnny Carson, Beverly helped a whole generation of Americans to fall in love with opera.

Unsurprisingly, every opera company wanted her. In the early 1970s, one of her signature roles was Marie, the titular character of The Daughter of the Regiment, and I was engaged to create a new production specifically to showcase her talents. The plot is pure high-calorie fluff. Marie, presumed to be an orphan, is raised by a regiment of soldiers. Sassy and tomboyish, she falls in love with young Tonio, but her plans to marry him are nearly derailed by the aged and fastidious Marquise of Birkenfeld (her long-lost aunt, later revealed to be her long-lost mother). As so often happens in opera, love wins out in the end. In order to appeal to as broad an audience as possible, we presented it in an English translation rather than the original French.

I got Beni Montresor to design a set that looked like a children’s cutout book — whimsical, colourful, and just plain fun. It was also very practical, all sliding flats and drops, and easy to transport. I believe the entire construction budget was a whopping $15,000. For the staging, I worked with Beverly on a characterization à la Lucille Ball — an operatic version of “America’s favourite redhead.”

This Daughter became a major hit, selling out houses from coast to coast. Our lovely set travelled endlessly to cities both big and small; in fact, it ultimately died of exhaustion and had to be rebuilt. We surrounded Beverly with a fine supporting cast that didn’t vary much from city to city. It was such a smash in San Diego that a picture of Beverly as Marie made the cover of the local telephone book.

In 1973 we landed at the Philadelphia Lyric Opera Company. For this engagement there would be a few notable changes. To begin with, it would be recorded for radio broadcast, which sounds quaint today but was quite a big deal back then. For the occasion, the company wanted to present it in French instead of English translation. And they wanted to make a few alterations to the cast. There was nothing unusual about any of this.

I was living in Europe at the time, and the singers arrived before I did. That was fine: they could use the time to rehearse the music alone. The moment I entered the venue, the venerable Academy of Music, I could sense something was out of whack. I ran into Beverly in the hallway and we had a huggy-huggy kissy-kissy moment. “How are the music rehearsals going?” I asked casually.

Her big smile and bright eyes narrowed. “You’ll see,” she said slyly.

Strange, I thought, as she continued on her way. I knew her well enough to know that this enigmatic look held an enormous amount of meaning.

I began to run into some of the other cast members. “You’ll see,” said Fernando Corena, a famous Swiss-French buffo specialist who had been engaged to play Sulpice, the sergeant in charge of the regiment. Then he laughed and hurried away.

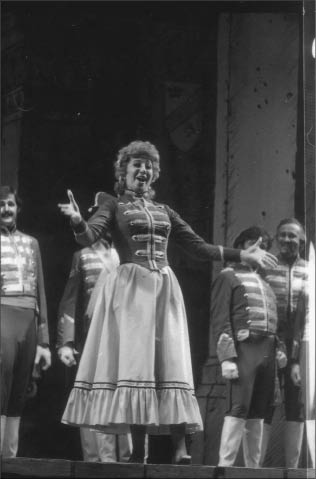

Beverly Sills in The Daughter of the Regiment, 1974.

Photo by Carolyn Mason Jones.

Next I cornered Enrico Di Giuseppe, our young Tonio. He opened his mouth as if to say something, then gave me a wan smile and shook his head. Now I was getting desperate to figure out what was afoot. I needed information other than odd looks and “you’ll see.”

Our first staging rehearsal was later that day, and I decided to start by running dialogue, which was especially important since we were performing in the original French. My cast trickled in, all old friends. But there was an odd feeling in the air, as if everyone was in on the joke except for me. Suddenly the door opened and in glided a stunning young lady. Statuesque, brunette, and barely of legal drinking age, she sported a slinky dress and an exquisite mink coat with matching mink hat. She could have been a model on her way to a photo shoot in Milan. My jaw dropped an inch or two. I wonder what role she’s doing? I said to myself.

This young lady — let’s call her Miss Connie — walked right up to me and thrust out her hand. “Mr. Mansouri,” she drawled, in the most extraordinarily contrived accent dripping with faux sophistication, “I understand you’re the stage director. I’m playing the Marquise.” I took her hand as if I was touching a space alien. “The … the Marquise?” I stammered. She nodded. “As in Marie’s mother?” Another nod. “Oh —” I said, trailing off.

Now understand this: the Marquise is Marie’s mother, a lady of advanced age. A funny old battle-axe, if you’ll pardon the phrase. She is invariably played by a fine character singer, typically one with major comedic chops who’s been around the block a few times. For most of our productions we had engaged the great Muriel Greenspon. I began to wonder where she might be.

Coming to, I realized I was still holding Miss Connie’s delicate, manicured hand. “Well, you’ve played this role before,” I said probingly.

“No, I haven’t,” she responded flatly.

My heart began to sink. “Do you speak French by chance?” I asked.

“No, I’ve never spoken French in my life,” she replied.

“Right,” I murmured. “OK, everyone, let’s sit down.”

I turned to face my otherwise veteran cast, all of them looking at me with what can only be termed bemusement. The collective thought balloon over their heads read, “Got the full picture now, Lotfi? So what are you going to do?” I put on a brave face and proceeded with the rehearsal. After all, anything is possible in the theatre. Maybe she has talents I don’t see, I thought.

We sat around a table to run the dialogue, with my veterans sailing through the lines as if they were native-born speakers. They had established a bubbly pace, milking the beauty of the language and timing the jokes wonderfully. Then we got to Miss Connie and everything stopped cold. She couldn’t pronounce even the first few words. But that didn’t stop her from trying. The very picture of concentration, she held the script just a few inches from her face and laboriously chewed each syllable. “OH … MOAN … CHERRY …” she droned, the words pulled out like taffy. It’s one thing to stumble over dialogue but this was outright butchery, like someone doing a parody of French. Interestingly, her ignorance of the language didn’t seem to bother her in the least.

It was taking her minutes to get through single sentences. With all the nonchalance I could muster I said, “Why don’t we do music.” As we moved to the piano I had a private moment with Miss Connie. “Perhaps we can arrange to have you work the dialogue with someone,” I told her.

“I have worked the dialogue with someone,” she replied.

As the accompanist launched into one of Miss Connie’s scenes, I silently pleaded, For the love of God, at least be able to sing. Well, the good news was that she could, in fact, sing. The bad news was that she was a soprano. Did I mention that the Marquise is a role for a mezzo-soprano? I began to sweat bullets. Rehearsal ended early that day. My veterans exited, the same bemused looks on their faces.

I rushed to the office of Anton Guadagno, the company’s music director, as well as the conductor for the production. “We have a major problem,” I said, speaking quickly. “Miss Connie is a beautiful young lady, but this is simply not the role for her. First of all, she’s a soprano! More importantly, you don’t want to embarrass Beverly by having her mother played by someone who looks like her daughter. Wrong voice, wrong look. And the French! This is a major production, and you are setting us up for disaster!”

In these pages I will readily confess to occasions when I’ve handled delicate situations by resorting to the shovelling of what might be termed offensive animal byproducts. Perhaps you are familiar with the phrase, “I’ve heard it so often I could set it to music.” Well, in my world the “shovelling” was so commonplace that I had literally set it to music in my head. The featured lyrics are “and the farmer hauled another load away.” And the jaunty tune, which, alas, is imperfectly communicated by the written word, is something very much in the vein of a children’s song.

On this occasion I found myself regaled by the tune. “Oh, Lotfi! I know you can make it work. You’re a genius! If there’s anyone who can turn this into a triumph, it’s you. And furthermore —” About this moment the music began in my head: “And the farmer hauled another load away …”

I wasn’t getting anywhere with Guadagno so I decided to reason with Miss Connie. Over lunch I tried to be as gentle as possible; she didn’t let me get very far.

“My dear, you’re such a beautiful young lady. Far too young to be playing such an old lady.”

“Oh, there’s makeup.”

“You’re a soprano.”

“I know I’m a soprano.”

“Yes, well the role is for a mezzo-soprano. And then there’s the French.”

“I told you, I worked with someone on it.”

“I’m not sure this is the best role for you.”

“Well, they told me I could do it.”

That was the end of that. I went back to Guadagno, only to be treated to an encore of “And the farmer hauled another load away …” this time modulated up a step and at a faster tempo.

After a few days of brutal rehearsals, and with time running out, I decided to change my strategy. Fortunately I had acquired some useful information and I intended to employ it to my advantage. I sat Miss Connie down and said, “Look, this simply isn’t going to work for you.” Before she could respond I whispered conspiratorially, “You know, I’ve just found out that they’re doing La Traviata next season. Now that’s the show for you! You would make a perfect Violetta. I can’t imagine anyone better suited to the role. You’d look so stunning in the gowns!” I did plenty of shovelling of my own before finally offering, “This role, the Marquise, it’s just going to end up as a humiliation.”

She managed to work herself into somewhere between a huff and a pout. Finally she agreed with me, saying, “This is a terrible thing. I’m very embarrassed.” Then, barely maintaining her affected accent, she added darkly, “Somebody should have told me.”

I happily delivered the news to Guadagno. Looking as if I had killed someone, he said, “There’s just one small matter, Lotfi. Miss Connie has a sponsor, you see. We’ll need to have a meeting with him.”

“Wonderful,” I beamed, thinking that the sponsor must be a voice teacher, or a patron of some kind. “I’d be happy to explain everything.” A meeting was scheduled for the next morning.

I breezed in sporting my best Persian-cat smile, utterly confident that I could handle the situation. It was like a lamb walking into an abattoir. Guadagno sat behind his desk, eyes cast down, nearly trembling. Miss Connie, once again dressed in her mink coat and hat, posed on a chair, legs crossed, hands folded on her lap, the very picture of wounded pride. There was someone else too, an odd presence. At first I could only sense him. He was like a black hole, and everyone in the room was gravitating toward him. It was something out of a Fellini film, a silent moment filled with a meaning that was about to be revealed.

Mr. Black Hole shifted, suddenly coming into view: a sinister figure sitting almost completely still with his face hidden by shadows, a camel-hair coat draped over his shoulders. His gaze locked on to me as he slowly and deliberately began to turn the fedora in his hands. If I didn’t know better, I would have guessed that he had been sent over from Central Casting to play the heavy in a film from the 1930s or 40s. He looked like a type tailor-made for Humphrey Bogart, Sheldon Leonard, or George Raft.

We all experience moments of supreme clarity. In an instant, we see things for what they actually are. The light bulb goes off. The smoke clears. The Buddha sits, enlightened. I had just such a moment with Mr. Black Hole. And my brain responded appropriately. Oh shit, I thought.

There was no formal introduction, and I knew better than to ask for one. I sat. It was not my opera company so I waited for Guadagno to make some kind of preliminary remarks. No such luck. After a tense minute or so, he muttered, “Well, Lotfi?” That was it. The ball was now in my court. As much as I suddenly wanted to, I couldn’t back down. It would have destroyed our lovely bonbon of a production. I had to take one for the team.

Once again I broke out my shovel. Human speech normally includes pauses and other such nuances, but these flew out of the window as I opened my mouth. “I understand you want to help this young lady with her career she is beautiful so lovely so young the role is for an old lady it’s in French she doesn’t speak French she has an absolutely lovely voice so lovely but she is a soprano not a mezzo unfortunately this role is not right for her.” I kept it up, expecting to be cut off at any moment.

Throughout my entire song and dance Mr. Black Hole looked at me from under his rather substantial eyebrows and continued to play with his hat. I had never known a picture of such calm to provoke such fear. When I paused to gasp for air he squared his shoulders ever so slightly, touched his chin, and in a low, raspy voice said, “Sumbahdy shoulda tol’ her.” That was all. There was no discussion. Just those few words hanging in the air.

As he and Miss Connie made to leave, I tried to end with something positive. “Look,” I said, “I understand they’re doing La Traviata next year …” Tears formed in Guadagno’s eyes as I outlined the potential for Miss Connie’s future work with the company.

The Godfather had just hit the cinemas a few months earlier, and of course I had seen it. The next morning, when I woke up in my hotel room bed, I was abnormally relieved by the absence of a bloody horse head. As I entered the theatre I once again ran into Beverly in the hallway. Without a word she took my head in both hands, and kissed me on both cheeks. Much later I told her all about the meeting with Mr. Black Hole and she nearly fainted from laughter. For the moment, though, we gave each other a knowing look and then rushed to get Muriel Greenspon on the phone. She was available and, as she lived in New York City, she was able to get on a train to Philadelphia in time for that afternoon’s rehearsal.

There was one last surprise. It turned out that Mr. Black Hole had purchased 750 tickets in advance. Who could have guessed that Miss Connie had so many fans? He returned every single one for a refund. It didn’t really matter. With Beverly as our star we still sold out every performance.