Intermission:

A Potpourri of Madness

In order to salvage a performance of Wagner’s The Flying Dutchman, I had to put someone’s personal salvation on hold. Fifteen minutes before curtain, the mother of the soprano portraying Senta barged into San Francisco’s War Memorial Opera House in order to save her daughter’s soul. A fundamentalist Christian, she believed that opera singers were under some kind of satanic influence. With the stage manager counting down the minutes to the curtain, she sequestered her daughter in a dressing room, quoting from the Bible and rocking like a true believer at a revival meeting. I didn’t have time to argue about the purported satanic inclinations of opera singers — and besides, my own experiences had left me suspicious of more than a few. Instead, I managed to convince the mother that God was so great that he could patiently wait one day. The curtain went up ten minutes late, but the soprano did go on. The next day the headline read, “SOPRANO FINDS GOD IN A SAN FRANCISCO OPERA DRESSING ROOM.”

Whenever I worked with Carol Neblett, she would always get close to me and look intensely into my eyes. I came to really appreciate her attentiveness, thinking, “Gee, that’s fabulous, she’s really interested in what I’m saying.” Until one day I realized that what she was really interested in was her own image reflected in my eyeglasses.

For the prompter, being holed up in a tiny box downstage centre means being in the thick of things but also occasionally in the line of fire. Prompters have to be able to deal with unexpected things coming their way, from errant props to broken bits of sets and costumes. There’s simply no place to hide. Not to mention the whole “show must go on” thing. One prompter, however, earned a gold medal for going above and beyond the call of duty. It happened during a production of La Fanciulla del West. I had not one, not two, but three horses onstage, and I suppose the law of averages made what happened inevitable. In performance one of the horses let loose with a revolting torrent, and the liquid streamed with unnerving precision directly toward the prompter’s box. The prompter, quite aware of his fate, calmly moistened a finger and traced a perimeter around the opening of the box. Perhaps it worked to deflect some of the torrent, perhaps not. I never had the heart to ask him.

In 1978 I created a new production of The Merry Widow for Joan Sutherland that toured throughout her native Australia. The set featured sumptuous belle époque furniture, including several overstuffed ottomans. While rehearsing a particularly complicated scene shift, the ottomans inadvertently got left behind. Exasperated, I yelled, “We can’t continue! The poufs are still on the stage! Get the poufs off the stage!” Half of the male choristers exited. Joan collapsed into such hysterical laughter that our rehearsal came to a grinding halt for a good ten minutes. And someone pulled me aside to explain that in Australia the word “pouf” had a slang meaning that I was unaware of …

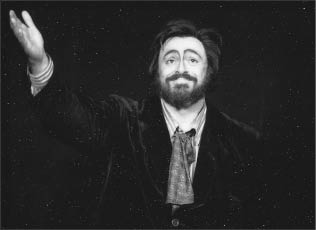

The mere sound of Luciano Pavarotti’s voice once prevented a mob scene. In the middle of a performance of La Bohème at San Francisco Opera an earthquake struck. I was standing in the wings, and the force of the temblor nearly knocked me off my feet. It happened to coincide with the conclusion of Mimì’s aria “Donde lieta,” after which there is a written silence that is broken by the tenor starting the concluding quartet. Unease began to ripple through the house and people began to make for the doors. Luciano, unaware of what had happened, walked to the prompter’s box and asked what the hell was going on. The prompter looked at him calmly and said, “Nothing. Sing! Sing!” So he did, starting the quartet with “Dunque è propio finita.” At the sound of his voice the patrons stopped in their tracks, looked back at the stage, and silently began to return to their seats. The palpable sense was, “If Pavarotti is singing, then things are all right.” The next day the local newspaper ran an article titled, “TENOR SAVES AUDIENCE FROM PANIC.”

Luciano Pavarotti in La Bohème, 1988.

Photo by Larry Merkle.

Innovating the use of projected translations in the opera house (Supertitles to some, Surtitles to others) is one of the proudest achievements of my career. But there is an art to the translating. Take the librettos of Hugo von Hofmannsthal: the writing is delicate and poetic, and the translations must be likewise. Librettos by Lorenzo da Ponte are unusually clever, and it takes effort to maintain their level of sophistication while communicating the humor in a way that modern audiences can appreciate. On the other hand, something simpler or melodramatic — many Verdi operas, for example — don’t require as much refinement. In other words, you always want just the right shade of meaning. And when things go wrong, it can be painfully obvious.

Tosca, in the first act of the eponymous opera, finds her lover, Cavaradossi, painting an image of the Virgin Mary. Coquettishly, she asks that he make the Virgin’s eye colour match her own. “Make the eyes dark,” would be a good translation. What one audience in Houston saw projected was, “Give her two black eyes.” The subsequent laughter prompted the Tosca, soprano Eva Marton, to stomp offstage. She demanded — and got — the titles turned off for the next performance.

When doing Die Fledermaus, Joan Sutherland once decided that since her character, Rosalinde, is impersonating a Hungarian when singing her showpiece number, the “Czárdás,” she would learn that difficult aria in Hungarian. She and her prompter Susan Webb worked tirelessly until they got it just right. Joan brought the house down every night. However, San Francisco’s preeminent music critic, who often disparaged her, blithely wrote in his review to the effect of, “As usual with Sutherland’s diction, she might as well have sung the Czardas in Hungarian.” He had no clue.

On top of the linguistic challenge, conductor Richard Bonynge added a number of cadenzas. Adding cadenzas to cadenzas is sort of like adding a banana split to a chocolate cake — it sounds delicious, but it can also be too much. Joan was just the person to pull it off though. And I figured, as long as we’re going this far, let’s go all the way. I asked her to add choreography to the cadenzas. “Lotfi, are you crazy?” she said incredulously. “Dancing and singing it at the same time? You must be joking.” Then, trouper that she was, she went ahead and did it.

W.C. Fields is purported to have remarked, “Never work with animals or children,” presumably because of the potential for being upstaged. This philosophy, at least in Gwyneth Jones’s view, extended to reptiles. She once essayed the title role of Elektra at San Francisco Opera, with tenor James King as Aegisth. The director, Andrei Serban, decided that Aegisth would manifest his decadence by having a live snake on him at all times. Oh, great, I thought. Just where the hell am I going to dig up a snake? Fortunately, one of our young resident artists happened to have a pet python — in all seriousness named Monty — that he graciously allowed us to use. Now I only had to worry about the sight of a python wrapped around James King’s million-dollar throat.

During rehearsals Gwyneth was all over the place, constantly upstaging James. Finally he had suffered enough. “Gwyneth!” he yelled. “Would you stand still? I’ve only got a few lines in this damn opera and you’re pulling focus!”

She looked at him intensely and replied, “But, Jimmy, you’ve got the snake!”

When I was directing at San Francisco Opera in the 1970s I was often called on to do interviews, appearances, and the like. Things were a bit more informal in those days, and one of the junior members of the public relations staff, a good-looking young man, would ferry me around in his personal automobile. It was always something of an adventure because he drove a tiny Volkswagen that was always filthy and filled with junk. One year I arrived to find him gone. “What happened to the nice young man?” I asked.

“I don’t think we’ll be seeing him again,” came the reply. “His writing has been getting a lot of attention. Have you heard of Tales of the City?” My informal chauffeur had been the then-unknown Armistead Maupin.

•

In a perverse way, I think superstar conductors may be responsible for an unfortunate trend in the classical music world: the rise of the arrogant, yet utterly incompetent, conductor. The problem is that a great like Leonard Bernstein or Gustavo Dudamel makes it look easy. And so a conductor of lesser talent (but greater ego) comes to believe that it is easy. I once worked with a conductor who believed he could conduct like Bernstein if, like his idol, he wore turtleneck sweaters and came to rehearsals with a towel draped around his neck.

Singers especially, with a dozen things on their minds at any given moment, need to feel as if they can rely on the conductor. The cardinal sin is being erratic with the beat. Alessandro Siciliani was notorious for this, constantly and inexplicably changing tempos and leaving singers hung out to dry. In 1984 when we were teamed up for La Rondine at New York City Opera, he was in particularly egregious form. Speeding up and slowing down almost literally from measure to measure, he drove the singers to distraction. It got so bad that at the dress rehearsal in front of an invited audience, Barry McCauley, an otherwise calm and professional tenor, yelled, “Goddamn it, make up your mind!” I tried to address this in private with Siciliani, only to run into a wall of arrogance. To borrow a baseball analogy, he was one of those guys who was born on third base — his father ran La Scala for many years — and believed he had hit a triple. “Lotfi, io sono spontano!” he crowed, waving his hand dismissively.

“Lovely,” I responded. “How would you feel if the singers were also ‘spontaneous,’ and paid no attention to you?”

Another cardinal sin is repeating a number in performance without prior agreement. It is an additional burden on the singers, for one thing, but it also sets a dangerous precedent: every other conductor feels they have to do it in order to show that they’re successful, and every audience demands it even if they don’t really want it. Singers become pawns in a game of one-upmanship. And yes, Siciliani was guilty of this as well. On the opening night of La Rondine, the second act concertante got a terrific ovation. Mugging to the audience, he repeated the whole thing. How nice for him. But he didn’t bother to consider that the music is vocally taxing and the singers weren’t prepared for it. They did make it through — barely — and it put them on edge for the rest of the evening. Beverly Sills, City Opera’s general director, was livid and the next day signs were conspicuously posted backstage: No Encores Are Permitted. By this point, though, the newspapers had mentioned the encore and audiences at subsequent performances wanted one for themselves. Siciliani responded to over-exuberant applause by facing the house and crossing his wrists in dramatic fashion. “My hands are tied,” is what he was indicating. The sheer gall irritated the singers, the crew, the orchestra — anyone who wasn’t Siciliani. When I saw his wrist theatrics, I thought, Give me some rope and I’ll do the job myself.

Renata Scotto and Lotfi.

Singers, as I’ve noted elsewhere in these pages, have nightmares about not knowing their roles. Directors have nightmares too — about singers. Specifically those singers who think they know everything, refuse to take direction, and are only out for themselves. Here is my version of the dreaded dream. Mind you, I’ve suffered it on several occasions, each time awaking in the middle of it: covered in cold sweat. It starts with a particularly frightening setting; a problematic opera house, for example. Oh, let’s just say La Scala. To add to the chaos, let’s make it a new production, because these always entail a slew of technical teething pains. Next we’ll need a difficult opera with many roles, all of them juicy enough to invite narcissism. Verdi’s sprawling Don Carlo comes to mind. If you’re not familiar with the work, a true story from the performance annals should shed some light: in a live performance, two big name singers — Franco Corelli and Boris Christoff — butted heads so often and so furiously that they started an actual sword fight during the auto-da-fé and had to be carried offstage. So, to sum up, our nightmare show is a new production of Don Carlo at La Scala. We may as well add labour strikes, corrupt officials, heckling audiences, power outages, overflowing toilets, and a few run-over puppies. At last we arrive at the lowest rung of hell where we meet the cast: Renata Scotto as Elisabetta, Fiorenza Cossotto as Eboli, Renato Bruson as Posa, Boris Christoff as Philippe, Ivo Vinco as the Grand Inquisitor, and the Lebanese tenor José Cura in the title role. And finally, just to obliterate even the slightest possibility of sweet sleep, to ensure that the Sandman pulls up stakes and makes for the hills, put conductor Alessandro Siciliani in the orchestra pit and have the whole thing reviewed by critics from San Francisco’s major newspapers, circa 1997.

The sheer horror of this scenario might not be readily apparent or understandable. If you doubt that such noted figures could inspire such terror may I simply say that you wouldn’t have wanted to be in my shoes — at least not without a pair of asbestos loafers.