Two Gentlemen in Verona

In spite of all of my maddening experiences in Italy, I always approached my work in that esteemed nation with optimism. Opera was born in Italy, after all. It’s just that often enough it didn’t take long for “hope springs eternal” to become “abandon hope all ye who enter here.” On one especially memorable occasion at least I didn’t suffer alone.

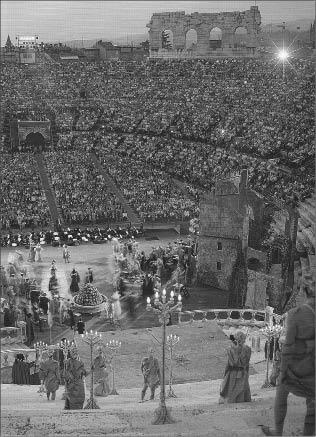

In 1995 the Arena di Verona Opera Festival invited me to create a production of Rigoletto to launch the season. An amphitheatre constructed by the Romans in 30 A.D., the Arena was first used for popular theatre during the Renaissance, and opera has been a fixture there since the early twentieth century. It is truly a venue like no other. The stage takes up one end of the oval-shaped playing field, with the surrounding bowl area often used for additional scenery. Currently it can accommodate an audience of 15,000 — almost four times the capacity of the Metropolitan Opera House, America’s largest. And yet the acoustics are crystalline. Attending opera at the Arena can be magical. Making opera there is another matter.

For my Rigoletto, the superb cast included Paolo Gavanelli in the title role and Ramón Vargas as the Duke. Nello Santi was the conductor, and I had my choice of designer. I wanted someone who could really take advantage of the Arena’s idiosyncrasies. Producing in the Arena is not like producing in a conventional opera house. To begin with, there is the obvious: it’s outdoors. The stage is sprawling. Attendance is huge, and the challenge is to create visuals that can be appreciated by someone in the farthest seat. A lot of directors go for something over the top. I sympathize. It’s hard to resist filling the immense space with every conceivable kind of frill. Franco Zeffirelli was especially prone to excess. One of his productions, as I recall, had such a complicated scene change that there was a ninety-minute intermission between acts one and two. Plenty of time to find your way to one of the surrounding osterias for a bottle or three of wine.

I decided to ask Günther Schneider-Siemssen to join me. More than a splendid designer, Günther was also a stagecraft pioneer. One of his innovations was the use of projections, something that he developed while working with conductor Herbert von Karajan. When it came to producing at the Arena, I had a feeling I would benefit from Günther’s ability to think outside the box — or inside the bowl, as it were. Also, it didn’t hurt that I got along with him well.

The Festival’s director, Mauro Trombetta, insisted that I arrive six weeks prior to opening night. Anywhere else in the world this would be welcome news. Six weeks for an opera director is an absolute luxury; there is time for very fine preparation. In Italy, however, a six-week rehearsal period invariably means the following: during the first two weeks, you will do practically nothing; during the following two weeks, you will stage bits of this and that with the chorus and perhaps a few comprimario (supporting) artists; during the last two weeks, the principal artists will finally arrive and you will stage the entire show in a mad rush of twenty-hour days. But I knew this going in. I took care to reserve a nice apartment overlooking the Adige River and rented a car.

On day one of my six-week “rehearsal period” I called the rehearsal department. “What is today’s schedule?”

“Oh, maestro, we are so sorry but the chorus has been granted a special day off in honour of the birth of Cangrande the Second’s great-great-great-great-great-great-great-great-great grandson. Please forgive us.”

“Don’t worry about it.”

Instead of rehearsing, I jumped into my car and explored the many vineyards surrounding Lake Garda, liberally sampling the regional wines.

The next morning, I called the rehearsal department. “What is today’s schedule?”

“Oh, maestro, we are so sorry. The key to the rehearsal studio has been misplaced, and the locksmith’s mother is quite ill and so he is making an emergency novena. Please forgive us.”

“Don’t worry about it.

Instead of rehearsing, I went off to the hilltop town of Asolo, a stunningly beautiful place where conductor Arturo Toscanini had a summer villa. After checking out the grounds, I planted myself on the veranda of the opulent Hotel Villa Cipriani where I passed the afternoon eating figs and prosciutto.

The next morning, I called the rehearsal department. “What is today’s schedule?”

“Oh, maestro, we are so sorry. The baritone’s spleen has an inflammation. Please forgive us.”

“Don’t worry about it.”

Instead of rehearsing, I went to Vincenza to tour the Teatro Olimpico, an eerily beautiful Renaissance theatre that is renowned for its permanent trompe-l’œil scenery — the oldest surviving set in existence. For the first few weeks I called in every day and each time I ended up enjoying “Lotfi time” instead of rehearsing. Among other things, I got quite an eye-opening education on the many local villas designed by Palladio.

Finally we got down to business. Günther’s design was both beautiful and nimble — out of necessity. In Rigoletto changes of location happen quickly. The first act lasts a scant sixteen minutes; if I asked the audience to then endure a ninety-minute intermission I would likely be run out of town. Günther addressed this by creating a series of four periaktos — three-sided structures, each about ten feet wide by twenty feet tall, with each side illustrated as a different location. This meant that with a simple turn of the periaktos we would have one of three settings: a garden, a salon, or an alley. These could even be mixed and matched: one side of the stage could be set indoors in the salon, and the other side could be set outdoors in an adjoining alley, and so forth. Scene shifts would be brilliantly fleet. But Günther didn’t stop there. To help illustrate mood and environment, he planned original projections to overlay onto the surrounding bowl area. This was especially useful for creating the storm called for in the last act. I had been wondering how we would pull this off, but Günther was way ahead of me. His projections would effectively evoke rolling clouds, sleet, and lightning. He even somehow talked the Festival into buying twelve state-of-the-art PANI projectors.

Günther’s plan presumed that this part of the bowl wouldn’t be filled with bodies. Some shows sold so well that every part of the bowl — even the area around the stage that offered limited views — would be needed to accommodate spectators. But according to Trombetta, Rigoletto was one of those shows that never sold terribly well. “The cheap seats will be vacant,” he told us. “Do whatever you want.” Perfect, we said.

We carefully placed the periaktos on the stage. It was essential that they be in just the right spot because our projections would be aimed over them at a specific angle. All we needed was time to set the twelve PANI projectors. Of course, this couldn’t be done during the day. Such sophisticated projections had to be plotted in the darkest of dark, which was roughly 10:00 p.m. to 5:00 a.m. Over the course of our precious rehearsal nights in the Arena we spent every minute of available darkness focusing them in the bowl area. Even a millimetre made a difference and Günther, a bit of a fanatic, worked with surgical precision. Meanwhile, I finally had the whole cast available to me. Working frantically, we somehow got everything staged. The dress rehearsal, for a blessed change, went beautifully. Alas, the old stage adage is: “Bad dress rehearsal, good opening.” And all too often the reverse is true. I began to worry.

It turned out that Mr. Trombetta was quite mistaken about Rigoletto. Opening night sold out, and they quickly started to sell the “cheap seats” that we were told would be empty. Unfortunately, all you could see from these seats was the back of our periaktos. Günther and I arrived at the Arena dressed up in our tuxedos to an unusually solicitous Trombetta. “Oh, Maestro Mansouri! Maestro Siemssen! We are sold out! Can you believe it?” After a round of beaming back and forth he got down to business. “Your sets — they’re blocking the view,” he said. “Could you move them just a little? The poor patrons on the sides, they can’t see anything.” With a sinking feeling, I carefully explained how this was impossible. The periaktos had been positioned perfectly, down to the millimetre. Moving them even a little would skew our carefully plotted projections.

Rigoletto at the Arena di Verona.

“Move anything and you may as well have no lighting at all,” I said, my exasperation building.

Trombetta went to Günther who gave an altogether more incisive response. “Scheiss theater! Scheiss theater!” (“Shit theatre! Shit theatre!”), Günther screamed.

Trombetta appeared to relent and our performance started. The people in the cheap seats, of course, couldn’t see a damn thing. Italian audiences are notoriously vocal, and as the first act progressed they began to moan and growl. Then they started their signature move: at the Arena, when they don’t like something, they take an empty wine bottle and let it roll down the ancient stone steps. Given the Arena’s exceptional acoustics not a single clink or clank goes unheard.

After Act One Trombetta bypassed Günther and me and ordered the stagehands to shift our periaktos twenty feet upstage — directly into the path of our projections, which now became surreal, like one of those late Picasso nightmare scenes. Günther was absolutely livid. When I left him, his shouts of “Scheiss theater!” were echoing through the colonnades of the Arena. As for me, I washed my hands of everything and made my way to a nearby osteria where I ordered a double scotch. So much work gone to waste.

Apparently, the audience liked the performance well enough. Toward the end my assistant tracked me down. “Maestro, you must come for your curtain call.” But by that point my next double scotch was more important to me. I waved him off. Mentally, I was already on the plane back home. As for poor Günther, ever the meticulous professional, he was on the verge of requiring hospitalization. It seemed that the only words remaining in his vocabulary were “Scheiss theater.” I did drop in on the cast party. Trombetta was very pleased with how things had gone. “Maestro,” I told him, “I have an idea. Directors, designers, rehearsals — why bother with them? Just wait for opening night and put up whatever set pieces you can find. Think of how much you’d save!”

I don’t think he got my point.