Finale:

Lotfi's Song

Things went right far more often than they went wrong. But even if the opposite were true, I wouldn’t have traded a minute of my life in opera for anything. Mishaps, miscues, mistakes — all become minor when I recall the joys, revelations, and pleasures. And, frankly, opera, or any high art, can accommodate a little madness. Maybe it’s even necessary. The higher the art, the greater the stakes. If it were all perfection, we might just go stark raving from too much beauty.

Often enough I was in heaven. No, Valhalla. There I dwelt among operatic gods and goddesses: artists who gave me moments to treasure, each one an equally joyous memory. I cannot recount the madness without also paying tribute. Here, in no particular order, are some of the gods and goddesses who were closest to my heart, and who I would like to salute.

Graziella Sciutti must have been whispering in Mozart’s ear as he wrote his operas. Or so I used to tell her, so pitch-perfect were her portrayals of the great composer’s “na-na” roles like Susanna, Zerlina, and Despina.

Motivating a characterization is a key skill for any performer, but no one used it to better effect than Inge Borkh. Her Elektra was all the more tragic because every aspect of her performance — subtle, detailed, and devastating — left no doubt as to the ultimate outcome.

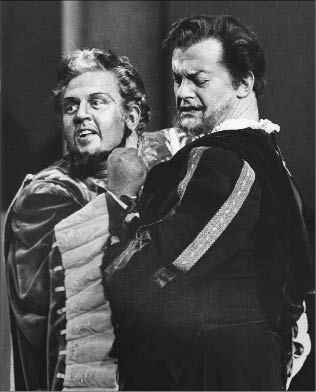

Plácido Domingo and Lotfi.

Photo by Jonathan Clark.

Tatiana Troyanos excelled in wildly diverse roles, including Eboli in Don Carlo, Dorabella, and the Composer in Ariadne auf Naxos. But even more notably, whenever the curtain went up she plunged into each moment so thoroughly that she became a taut wire, a source of pure electricity. And it was infectious: when she walked onstage everyone brightened.

It’s not a good idea to erect statues to living people, but an exception can be made for Plácido Domingo. With his voluminous memory, extraordinary concentration, and unbelievable longevity, he stands unequalled. But what was always most impressive to me was his ability to find the truth of his portrayals almost entirely by instinct. Why am I speaking of him in the past tense! He is still active today — busier, in fact, than many singers half his age.

Disciplined and un-neurotic, Johanna Meier confounded the worst stereotypes of the prima donna. She delivered performances of such consistent excellence that many took her for granted. Though brilliant in roles like Tosca and Minnie in La Fanciulla del West, she didn’t hesitate to tackle Isolde at my suggestion, not just rising to the occasion but soaring to it. I found that I actually had to encourage a bit of egotism on her part, essentially giving her an excuse to be even greater than she already was.

Charming, scheming, and yet lovable old men — Dulcamara, Gianni Schicchi, Don Alfonso, and the like — are portrayed by a special breed of singer: the buffo. Renato Capecchi, Paolo Montarsolo, and Sesto Bruscantini were my very favourites of this breed. Each was part of a long and distinguished tradition, and yet each was unique.

There’s a good way to be obsessive and a bad way: Nicola Rossi-Lemeni was obsessive in the best way. It’s unsurprising, therefore, that he could effectively span intense emotions, from childlike wonder as Don Quichotte to true insanity as the title character in Wozzeck. He was also capable of turning his mania inside out to become riotously funny in buffo roles. Blessed with the soul of a poet, he would often stop in the middle of a walk to recite verses. It wasn’t a hallucination: the muse had invaded him, and his companion of the moment simply had to wait it out.

Elizabeth Söderström was perhaps the most intelligent singer I ever worked with — her ability to speak ten languages fluently was just the tip of the iceberg — but what impressed me most was her authenticity. She simply couldn’t do anything superficially, not even a soufflé like The Merry Widow. Without vanity to get in the way of judgment, she enjoyed a well-paced and lengthy career that logically started with Mozart and ended with Janáček.

While no slouch when it came to sheer vocal power, Tito Gobbi was a master of the mezza voce. As Iago, he was able to sing “Sogno, era la notte” in a chilling, insinuating whisper that was more frightening than any full-throttle approach. In fact, he could accomplish more with a single word than other singers could in an entire aria, as I witnessed when I worked with him on Simon Boccanegra: in the crucial moment, when he acknowledges his daughter with a simple “figlia,” time stood still.

Donald Gramm was generally considered to be a connoisseur’s artist. I think the reason he wasn’t more appreciated in his own time is that back then Americans believed only Europeans could be great opera artists; some singers even adopted more European-sounding names in order to be taken more seriously. But Donald was an all-American who boasted classic old-world skills. Sophisticated without being conceited, he was unrivalled in roles such as Henry VIII in Anna Bolena and a truly evil Doctor in Wozzeck.

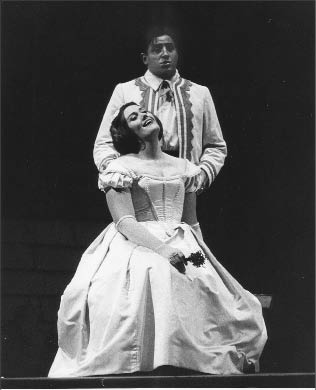

Leontyne Price in Il Trovatore, 1981.

Photo by David Powers.

James McCracken and Tito Gobbi in Otello, 1964.

Photo by Carolyn Mason Jones.

Maureen Forrester was one of Canada’s better-kept secrets. Mostly active as a concert artist, she nevertheless challenged herself with new and difficult roles, like Klytaemnestra in Elektra, Brangäne in Tristan und Isolde, and the Prioress in The Dialogues of the Carmelites. Consistency was her hallmark: her performances were predictably terrific.

Though Ragnar Ulfung started out in lead Italian roles like the Duke in Rigoletto, Cavaradossi in Tosca, and Gustavo in Un Ballo in Maschera, it never was the best fit. Ultimately he became a master of niche roles like Tom Rakewell, Mime, and even Koko in The Mikado. To me, he stands out for his theatricality and exceptional dignity.

For sheer visceral thrills, Jon Vickers tops my list. I couldn’t say his sound was particularly beautiful, but it was virile and tonally distinctive. I will forever have the sound of his Florestan in my head.

Leontyne Price had a voice like lava: molten, smooth, often fiery, and always unquenchable. Apropos, I will always associate her with the sizzling red dress she was wearing when I saw her perform Bess (with her then-husband William Warfield as Porgy). I was still a student at the time, but one look at how she filled out that dress and I thought, I want to be part of this thing called opera.

No one was more generous to me in so many different ways than James McCracken. Onstage and off, he had to give, give, give. It was simply his nature. I appreciated that he was unabashedly sentimental as well.

All of the conductors in my Valhalla taught me specific works or styles in ways that would forever influence how I heard opera. Otto Klemperer, as mercurial as he was majestic, introduced me to Fidelio, though he nearly drove me crazy in the process. I learned Pelléas et Mélisande from Ernest Ansermet, who had learned it from Debussy himself. It was my privilege to introduce U.S. audiences to the fiery, prodigiously talented Valery Gergiev, collaborating with him on several great Russian operas that helped spark a resurgence of interest in that repertoire. And Charles Mackerras, as decent a human being as I’ve ever known, defined Janáček and Strauss for me.

I would like to single out four designers as well, each representative of different aesthetics. Thierry Bosquet was a master of a mostly bygone approach that favoured beauty for beauty’s sake, such as characterized the belle époque. Several of the productions that he created for me, including Louise and Pelléas et Mélisande, were akin to living paintings. In the many productions he designed for me at Zurich Opera, Max Rothlisberger unfailingly let the particular opera dictate the look — a refreshing contrast to many a designer’s penchant for cultivating an idiosyncratic style that reflected more on them than on the opera itself. Beni Montresor specialized in magical fairy tale productions of works like Esclarmonde — never anything realistic, but always something fantastic and crowd-pleasing. And no one was more skilled with avant-garde designs, above all incorporating the use of projections, than Günther Schneider-Siemssen.

Unsurprisingly, all of these gods and goddesses had certain traits in common. In terms of personality, all were intensely dedicated. Most were remarkably down to earth, and quite a few were unusually hard on themselves. All possessed remarkable range, adept at both comedy and tragedy, capable of extremes of lightness and darkness. All lived their assignments fully, imbuing them with every shade of humanity. Most importantly, all were capable of achieving an ideal marriage of music and drama, resulting in intense veracity — the genuine emotional, intellectual, and spiritual reality of the moment. This was true music-theatre.

Their artistry was my education. I didn’t really know Elektra until I worked with Borkh; her triumphal dance at the opera’s end, which went from near-paralysis to superhuman frenzy, is burned into my brain. Scarpia had always been something of a two-dimensional villain to me until I saw Gobbi tap depths of sadism and lust that made the character simultaneously disturbing and irresistible. “Verdi soprano” was just another term to me until I heard Leontyne. From my trio of Italian buffo masters I learned that comedy is always based on truth and never artificial, requiring immense discipline and mastery of the text. The whole essential concept of song starting from nothingness was made crystal clear to me when I heard Vickers pour out “Gott! welch’ Dunkel hier!” My conductors were critical to pressing the boundaries of what was possible with an orchestra, and championing forgotten composers and works.

Furthermore, my gods and goddesses wove themselves nobly into the fabric of the operatic tradition, inheriting from the masters who came before them and passing the torch to those who came after them. Take Sciutti, for example. After she retired from the stage, I invited her to direct at San Francisco Opera, and to instruct our resident artists on the finer points of Mozart style. Among those young singers were Anna Netrebko and John Relyea, two artists of a new generation who I count as incipient members of my personal Valhalla. When Söderström retired the roles of Emilia in The Makropulos Case and the Marschallin in Der Rosenkavalier from her repertoire, I asked her to co-direct those works with me in order to pass on her knowledge to younger artists. Those performances are among the most bittersweet in my memory: a brilliant interpreter lived on, and, more importantly, a brilliant interpretation was passed from one artist to another.

Anna Netrebko and John Relyea in Le Nozze di Figaro, 1998.

Photo by Larry Merkle.

Finally, I have to single out the one artist who meant more to me than any other. She stands apart here as she did for me in real life. One last story.

“Oh, dear. You want me to fall to the floor?” Joan Sutherland fixed me with what I thought was a baleful eye. As I fumbled for a response, I couldn’t help but think that I had committed a major faux pas. Joan was one of the greatest sopranos in the world, and here I was suggesting — meekly, I had thought — that she should let her celebrated self collapse onto the stage. Normally I wouldn’t have dared, but I felt the dramatic exigency of the moment demanded it.

“Well,” I said, backpedalling quickly, “uh … How about … Why don’t you lean into the arms of your mother instead?” motioning toward the nearby Dorothy Cole.

Joan drilled me with her eyes before replying in her broad Australian accent, “No! Listen, Lotfi, why don’t you insist I fall to the floor as you damn well know I should do!” With that, I began to fall in love with her.

Later in that same production, I went head over heels. This was my very first show at San Francisco Opera — the year was 1963 — and I was still relatively green. General Director Kurt Herbert Adler hovered in the wings, smoking his pipe, and waiting for the chance to meddle. As I was staging a scene involving Joan and the chorus, he walked up and began to tell me what to do. Joan stopped him with that famous stare and said, “Mr. Adler, this happens to be Mr. Mansouri’s production. And by the way, don’t smoke onstage.” She was one of the very few people who could have kicked Adler off the stage, and she did it for me.

Joan, I thought, I think this is the beginning of a beautiful friendship. It was.

Over the course of the next few decades, I would direct her in multiple productions of nine operas: Anna Bolena, Die Fledermaus, Esclarmonde, Hamlet, Les Huguenots, Lucrezia Borgia, The Merry Widow, Norma, and La Sonnambula. All told, she worked with me more than any other stage director. Part of it was coincidental — work in opera long enough and you cross paths with people over and over. But once it became known that she was comfortable with me, I think companies went out of their way to put us together. Eventually, we knew each other so well that we could practically read each other’s mind. Staging her became one of the most joyful experiences of my entire life.

Joan Sutherland and Renato Cioni in La Sonnambula, 1963.

Photo by Pete Peters.

Joan had a glorious career because she took good advice and managed to marry someone, Richard Bonynge, who was capable of giving it. In pushing Joan to perfection, Richard was knowledgeable (his personal collection of original handwritten scores is legendary), demanding, and even something of a Svengali. Their stories have been well-documented elsewhere, and I don’t need to repeat highlights here. What is worth mentioning is how they did it together.

My comfortable working relationship with Joan eventually became a real-world friendship. It can be hard for anyone to find meaningful intimacy, but it’s all the harder in the theatre, with all of the coming and going. Her modesty was astounding: while a great singer, she was never a grande dame. The woman behind the stunningly successful opera singer was a warm and down-to-earth person — a mother, grandmother, and loyal friend.

Our closeness was probably the deciding factor in making possible one of my fondest memories of her as an artist. When I was general director of the Canadian Opera Company, one of my dreams was to have her do Ophélie in Hamlet. My staff thought that I was on the moon. Ophélie is a teenage girl. Joan was nearly sixty years old. When I first mentioned it to her she demurred, saying, “Oh, Lotfi! I’m a granny!”

But I was determined. “Joan,” I countered, “you know, when these glamorous movie stars got older — people like Marlene Dietrich and Lana Turner — they still played younger characters. They just put a little gauze over the camera lens.”

Giving me her famous stare, she retorted, “My dear, for me they’d need burlap.”

She could sing the part of course — she had already recorded it, though she had never done it live — but she was self-conscious about looking the part. It wasn’t a matter of vanity. She was concerned for the audience, that her as Ophélie would strain dramatic credulity. I practically had to seduce her. It came down to making her feel comfortable while creating something believable for the audience. Meanwhile, many of my colleagues tried to change my mind. Too old, they said. They all seemed to have the image of Jean Simmons from the Olivier film in their heads. But I couldn’t shake the thought of seeing her sing the mad scene in front of a packed house. Eventually Joan agreed, and I scheduled Hamlet for our 1985 season.

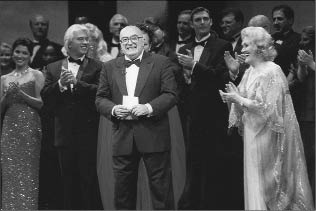

Lotfi’s farewell as the General Director of SFO, with Anna Netrebko, Dmitri Hvorostovsky, and Joan Sutherland.

Photo by Robert Cahen.

The O’Keefe Centre, Toronto’s opera house at the time, could seat over three thousand people. Each and every performance was sold out. I commissioned a production that put her in the best light possible and staged her with supreme delicacy. For the mad scene, she glided through a bucolic setting of rushes, weaving ethereal sonorities of madness and pain. At the climactic moment, she landed perfectly on a stratospheric note and held it for an eternity as she walked into the lake built into the back of our set. What followed was one of those magical silences that opera lovers live for: realizing that they had experienced something of almost supernatural beauty and heartbreak, everyone froze, not daring even to breathe. And then, after moments of unbearable suspense, everyone exploded in delirious applause that I thought would never end. It was about as cathartic a moment as I ever experienced. Joan was pleased, but also relieved: all she wanted was a good experience for the audience.

The next day I made a point of tracking down my doubtful colleagues. “You see?” I told them. “That’s why I wanted Joan.” When all was said and done, she wouldn’t have done the production for professional reasons alone. She took a chance because we were friends. And I’ve never been more grateful for anything.

Even in retirement, Joan continued to do me favours, appearing at galas, leading master classes for young artists, and the like. Every time we got together felt like old home week. My friendship with Joan was another instance of kismet — unexpected, endlessly gratifying, and unflagging. Astounding, like the woman herself.

When I retired, Joan and Richard sent a lovely gift: a framed picture from our very first production together when we were young and foolish, the 1963 La Sonnambula at San Francisco Opera. The inscription reads:

If only there had been more like you! You brought great joy into our lives. Every one of the many productions we did together is stamped on our memory. We have wonderful memories of times spent with you and Midge and hope we may still spend happy hours together.

The gods and goddesses of my Valhalla gave me visceral pleasure, touched my heart, expanded my mind, nourished my soul. There are so many other artists I want to salute. Alas, for me to do justice to all of them I would need another book. Instead, let me say that in my heart I remember and treasure each one of them, and that I am thankful for what we shared.

Names on the page can only go so far in communicating what I experienced. Nevertheless, let them epitomize the breadth of magnificence I enjoyed. Let them reflect the long line of operatic greatness, one that started well before my time and, God willing, one that will continue long after I’m gone. As long as opera exists, let there be beauty such as I have known. Perhaps even a little madness.

And so it seems only fitting that now I want to sing. I want to sing to honour those with whom I worked. I want to sing to express gratitude for my career. I want to sing to celebrate opera.