Overture:

Lotfi in the Underworld

Once upon a time I was a fledgling opera singer. Almost immediately I learned a basic tenet of my new art: things go wrong. Horribly wrong. Often. And yes, I found out the hard way. It was the mid-1950s, and I was a callow young student in the Opera Workshop at the University of California, Los Angeles. My very first major assignment was the title role of Monteverdi’s L’Orfeo. It was a big, big deal. Dr. Jan Popper, the head of the workshop, had commissioned a new English translation. The orchestra adopted period instruments — this, well before such a thing became fashionable. We would perform in front of a capacity audience at the 1,800-seat Royce Hall. And this would be the work’s local premiere.

It’s not as if I didn’t try, which is how I learned a corollary to the basic tenet: preparation won’t necessarily save you. I applied myself and studied hard. We all did. The atmosphere was electric. Rehearsals ran deep into the night as we worked on every last detail. We felt more than prepared. Then they let the audience in.

In the opening scene, Orfeo (me) sings an aria to his companions (the choristers and dancers). I moved into position and raised my prop harp. The orchestra started up. I looked into the house to see thousands of eyes looking back at me — and suddenly I couldn’t remember a damn word. I looked to my companions who all looked back at me with earnest smiles. They were acting. I was panicking. With my musical entrance fast approaching, I discovered another corollary: when things go wrong, you must “fake it ’til you make it,” as they say. I had enough presence of mind to remember that the aria was about nature so I began to sing whatever “nature” words came to mind. “Oh the water of the trees and flowering rain of the rainbow is the fawn in full bloom on the moon and the sea and the stars of the earth and the skies …” I made it to the end of the first verse. Whew, I thought. Thank God I have a whole musical interlude to remember the words to the second verse. No such luck. The second verse was almost a word-for-word reprise of the first. During the next interlude I looked around to see that my companions’ smiles were now frozen, their eyes filled with surprise and fear. The third verse approached — my last chance to get at least some of the words right. But it wound up sounding suspiciously like verses one and two. Mercifully it ended. And then I heard a startling sound: applause. Later the translator tracked me down. Here it comes, I thought. He’s going to say, “You ass! You ruined everything!” Instead he congratulated me effusively. He hadn’t even noticed! And thus I learned yet another corollary: the audience doesn’t always know when something goes wrong.

Orfeo at UCLA.

Later in that same production this corollary was reinforced. During the intermission I heard a great commotion backstage. It seemed that the soprano singing the role of Euridice had lost her voice. Dr. Popper didn’t want to announce her indisposition, feeling that it would destroy the atmosphere. So we improvised. As it happened, a member of our chorus had been studying the role all along. She had essentially been covering the part as a personal exercise, but she had become familiar with the music only, not the rather detailed staging. Needless to say, we couldn’t very well throw a costume on her and send her onstage. It was finally decided that she would sing the part from the wings, while our indisposed soprano acted. We were all unsatisfied with this proposed arrangement, fearing that it would rob the performance of much of the intimacy we had worked so hard to achieve. No, we needed to have the cover’s voice somehow sound as if it were coming from the stage. Finally we settled on something unusual: the cover would sing from beneath the stage, directly below her counterpart above. Our extraordinary coach-accompanist Natalie Limonick, score and pitch pipe in hand, assisted her every step of the way, and the indisposed Euridice lip-synced in front of the audience. Lip-syncing, of course, has become depressingly common these days, but back then it was still rare. My big third-act duet with Euridice was surreal: I looked into her eyes and watched her mouth move while the actual sound came from somewhere beneath my feet. But in this way the performance was saved.

By the final curtain I was in a fog. The whole situation seemed ridiculous. And yet we received a standing ovation. The audience was totally unaware of what had happened. Los Angeles’s major music critic wrote a positive review, noting that our Euridice seemed uncertain and lacked projection in the first act, but recovered in the third act and gave an excellent account of the role. Which brought me to yet one more corollary: critics often know less than anyone.

UCLA turned out to be my operatic boot camp. I gained a ton of experience as a singer, actor, director, designer, prop master, dramaturge, coach, and administrator. One time I put on the last act of Verdi’s Otello, in which I directed, managed the props, selected the costumes, set the furniture, designed the lighting — oh, and performed the title role, cuing the final curtain with a tilt of my head as I sang “un bacio ancora” (“one more kiss”) and embraced Desdemona. Incidentally, I had the luxury of pulling costumes from Hollywood’s iconic Western Costume. Remembering

Otello at UCLA.

that the 1947 film A Double Life included a scene in which the lead actor, Ronald Colman, portrays Shakespeare’s Othello, I went out of my way to track down that costume. It was available, and a perfect fit for me.

Like many aspiring performers I landed my first paying gigs while still a student. My partner for most of these gigs was another student and aspirant who would go on to become a legend: Carol Burnett. But for the Korean War we might never have met. One day I was working on an aria in a practice room and Irving Beckman, one of the music department coaches, burst in. “Are you a tenor?” he asked.

“I think so,” I replied.

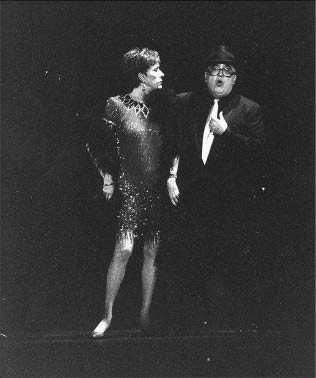

Carol Burnett and Lotfi at an AIDS fundraiser held in the War Memorial Opera House in San Francisco, reviving their UCLA-days duet from Guys and Dolls.

“We need you,” he said. It turned out that he was working on an act and his tenor had just been drafted to serve in the Korean War. I stepped in as the replacement and my partner turned out to be none other than a young and unknown Carol. It went well enough, and we were subsequently hired to sing at luncheons, lectures, and the like. Each gig paid what we considered to be a princely sum: five U.S. dollars. As far as we were concerned, we had made the big time, and goodness knows we needed the money. Our repertoire consisted mostly of numbers from great American musicals like Guys and Dolls, Call Me Madam, and Annie Get Your Gun, plus a sprinkling of opera standards. Even then she was a wonderful belter and a fabulous vocal stylist.

Carol would make television history with her long-running variety show, and part of the fun of watching was the unpredictability; those moments when she or one of her colleagues would crack up were delicious. I can personally attest that this charming quirk of the show had forerunners. During our student gigs I would often fumble lines and

Carol Burnett and Lotfi.

she would make a bit out of my goofs. If lyrics slipped my mind, for example, I might repeat what I had just sung, only to have her hold up a hand and deadpan, “You said that already, Lotfi.” It never failed to charm an audience, and often enough left me trying to stifle laughter.

She didn’t hesitate to harpoon an audience either. On one occasion we were hired to sing at a rally for Richard M. Nixon, who was campaigning for vice president. (When it came to gigs we were apolitical. All that mattered was the five dollars.) The scandal du jour was that his wife, Pat, had acquired a new mink coat. To read the papers you would have thought the very fate of American politics rested on her wardrobe. The Nixons arrived in the middle of one of our numbers and, without hesitation, Carol stopped, eyed both of them, and insinuatingly said, “Oh, Mrs. Nixon, what a lovely new coat.” Another time we were performing outdoors on campus — it was probably some sort of lunchtime event organized by the student union — and we got heckled by a bunch of drunken frat boys. One of them started up a fire extinguisher and tossed it onto the stage, where it spun in lazy circles, the squirting fluid acting as a jet. Carol moved to the edge of the stage, leaned toward them, and seductively drawled, “Boys, I knew I was hot but I didn’t know I was that hot.” It was instantly obvious that they weren’t going to win a war of words with her and they didn’t bother to press their luck, instead slinking off.

I fantasized about going on to a long career as a professional singer but, as so often happens in the theatre world, things didn’t turn out as planned. I began to veer away from performing immediately after I graduated, accepting an appointment as an associate professor in UCLA’s Music Department. And over the next few years I got a real world education — one that would help me settle my career course once and for all. It was all a wonderful case of kismet, something that I believe has shaped my entire life.

In the summer of 1958 my voice teachers, Dr. and Mrs. Fritz Zweig, asked me to accompany them on a trip to Europe as their driver. Fritz Zweig, cousin of famed writer Stefan Zweig, had been a prominent conductor in Germany, and his wife, Tilly DeGarmo, was a lyric coloratura at the Vienna and Berlin opera houses; fleeing the Nazis, they landed in California along with people like Otto Klemperer, Bruno Walter, and Lotte Lehmann. For me this trip through Europe was like a post-graduate course in history, music, and art, with Dr. Zweig as a knowledgeable professor and guide. I felt as if I were experiencing opera for the first time. There was Adriana Lecouvreur in a sumptuous production at La Scala with Magda Olivero, Giulietta Simionato, and Franco Corelli. I saw Richard Strauss’s Arabella at the Salzburg Festival with the dream cast of Lisa Della Casa, Anneliese Rothenberger, and Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau, conducted by Karl Böhm and directed by Rudolf Hartmann, a protege of Strauss. At Munich Opera, Hans Pfitzner’s Palestrina, a truly grand opera, blew my mind, with one portrayal, that of Cardinal Borromeo, standing out. Afterward I learned the name of the bass who sang it — Hans Hotter — and years later, as general director of San Francisco Opera, I would engage and direct him in the role of Schigolch in Lulu. He was close to eighty years old by then but still had tremendous energy and concentration. Working with him was a pure joy, as well as a touching illustration of how my career had come full circle.

In the summer of 1960 I participated in the young artist program run by Friedelind Wagner, granddaughter of the great composer Richard Wagner, at the Bayreuth Festival, which, among other things, gave me the opportunity to observe director Wieland Wagner in action. His Parsifal was one of the most perfect productions I had ever seen, with each element — music, drama, and visuals — creating a harmonious whole. At the end of it I was emotionally drained, and found that the sheer force of it had brought me to tears. Later that summer I assisted Dr. Herbert Graf, one of the most influential opera directors of the twentieth century, on a production of Verdi’s Otello in Venice with Mario Del Monaco and Tito Gobbi, presented in the courtyard of the Doge’s Palace. This was a world of passion and emotion quite different from Bayreuth, but thrilling in its own way.

With each of these experiences I sensed, perhaps even without fully understanding, that I was being irresistibly drawn to the life of a stage director and impresario. My métier would be to guide opera rather than to perform it. To complete my transformation I would need the mentor of a lifetime, and thankfully I found one in Dr. Graf. At his invitation I became resident director at Zurich Opera in 1960, and under his tutelage I learned my craft.

Over the course of six decades I have directed over five hundred productions and held the top leadership post at two of North America’s largest opera companies. But throughout my career, from decade to decade, at opera houses big and small, the basic tenet that I learned firsthand in L’Orfeo has remained a constant. I’ve seen mishaps, miscues, and mistakes, some funny, some painful. This book presents some of the more amusing (at least in retrospect) episodes. Certain names have been changed to protect the guilty. But otherwise every single episode is true. I was there.

To quote the great Canadian comedienne, Anna Russell, when she described the story of the Ring: “I’m not making this up, you know!”