Chapter 4 - Boxer and Smokey

The railway bridge creaked and whined as the steam trains shunted backwards and forwards all day. The trains went to the turntable to turn around further down the track. On the subject of this old turntable, I had a narrow escape one day as I was climbing underneath it, picking up bits of coal for my campfire - only a little, just enough to keep the campfire going. Anyway, while I was under the turntable, a train came along to turn around and go back up the track to carry on shunting. I was stuck - and I mean stuck - under the turntable, which heaved and groaned because of the weight of the train. I couldn’t get out anywhere! The red-hot steam poured all over me, I was beetroot red for days on end, which taught me a lesson for the future.

We also played sometimes on the river bridge. We were not supposed to really as the bridge was wide and the river deep. My mum and dad were always telling me to keep away as there were spikes on the river bottom left behind by bridge workers. We would play chicken on the river bridge, hanging from the sleepers in a row as the train approached with red-hot steam pouring out. We stood the pain of the steam all over our bodies for as long as we could. The one who dropped into the river last was the winner.

A short wind blew my baggy hand-me-down trousers as I walked. I hated having to wear my cousin Tom’s cast-offs. I felt it was my turn to have brand-new trousers.

I continued along the riverbank, making my way towards the brickyard. Although the site was disused, the brick dust still blew in circles with leaves from a nearby oak tree. Away from the brickyard entrance gates, I would creep through a gap in the barbed-wired fence. Old bricks and stinging nettles make the trek heavy-going.

In temper, I swiped the nettles with my willow stick, but with my bare arms uncovered the nettles won the day, leaving me with painful bumps.

The old brick kilns, standing empty, told a story of how things were changing because of the war. The men that used to work the kilns were now fighting for our country in faraway places. Before the war, the men used to sing all day, happy in their work. Laughing and smiling they used to be, there in the brickyard, before war came. When I was very young, my dad once took me there with him. I watched the bricks being taken out of the kiln and loaded on to trucks. The bricks were a green colour before they went into the kilns. It was great fun to watch the finished bricks being fetched out of the kilns (three of them in a row). They were huge dome-shaped buildings made of corrugated sheets. Inside were huge blocks which heated up the kiln to cook the bricks, so my dad told me.

Apart from the sound of the dust and leaves still chasing in circles, there was now but an eerie stillness. Venturing to the entrance of the nearest kiln, I stood motionless, looking inside. The far end was dark and spooky and gave the shudders to my small frame.

I was just about to leave the kiln entrance when I heard a sound coming from the far end inside. I went outside to see if I could see anything from the back or from the side of the kiln. Out of the top of the kiln I could see a finger of smoke. Something or someone must be inside. I went to the front of the kiln again to listen further. The brickyard was surrounded by trees. I wondered if something might be watching me from there. An old tap next to the kiln broke the silence as I stood motionless. It made a gurgling sound for a short time and then it stopped; then it started again. Someone or something had been using it and hadn’t turned it off properly - but who? Silence again made me think it might have been just my imagination.

About to walk away, I heard for definite the muffled sounds of something in the kiln. Stealthily and gingerly I crept to where the sounds were coming from. In total darkness, and with both arms outstretched in front of me, I began to feel as best I could with my feet for potholes or broken bricks. As I fumbled in the dark, I suddenly remembered picking up a book of matches from the roadside earlier that morning. My trouser pocket had several holes, but luckily the matches were still there.

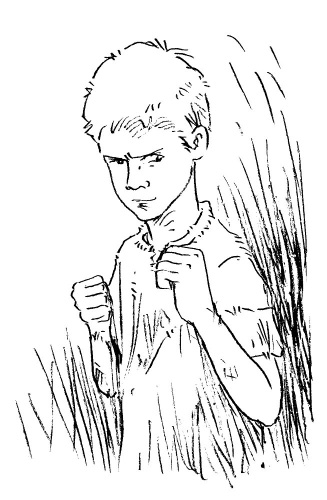

The burst of the ignited match forced me to stand rigid with fear. The light drenched the corner of the kiln to reveal a boy standing in the staunch position of a boxer, hands clenched and ready to fight.

“OK, OK, matey. What do you want and what are you doing here?” said the boy as the match flickered away, bringing total darkness again.

“I - I’m sorry,” I said, by now my teeth starting to chatter with fear. “I didn’t mean to disturb you.” I fumbled further for a new match. “H-have you got a candle, please?” I said, still shaking.

“A bloody candle is no good without a bloody match, is it?” said the boy.

I held out my hand with the book of matches waving in the darkness. “Here you are,” I said to him.

He snatched the matches from my hand and lit the candle.

“Why, you’re only a sprat of a thing,” said the boy with a look of contempt as he lit the candle. “One punch and you would be down.” He came closer to me, shoving his face into mine; he was but an inch away. “Any yap from you and you’ll get this fist straight in your gob - get it?”

I felt like crying, but held back for fear of further abuse.

“Why do you shout and scream?” I said, by now plucking up some courage. Adrenaline now began pumping in my body. “And, in any case, I’m only a little shorter than you. Not only that,” - I surged forward towards the boy - “I might just punch you one first!” I drew my right fist backwards. “My dad was an army boxing champion.” By now I held my left hand up as well as the right. “He showed me a lot and I might just use some of it on you!”

“Calm down, sprat,” said the boy as he tipped the candle to drip hot wax on to the top of an old orange box so he could stand the candle upright. He waited until the wax had dried and the candle was firm.

“Sit down there, sprat,” he continued as he brought forward another wooden orange box for me to sit on.

“My name is Matty, not sprat,” I retorted with some contempt.

“Yeah, OK, Matty,” the boy responded, giving a couple of nods.

“What’s your name?”

The boy moved uncomfortably on the makeshift chair.

“I,” - he looked over towards me, then back towards the floor - “I don’t have a name.”

“Everyone’s got a name.” I moved closer to the boy. “You just cannot have no name.” I moved closer still.

“I ain’t got a bloody name!”

The candlelight showed a trickle of tear from his eye.

“Without a name, how can you be anyone?” I said, very concerned.

Yes, yes, I ain’t nobody - OK, clever clogs.”

The boy stood up, shaking his head and running his hands through his thick, unkempt mousy-coloured hair. I moved back to where I had been standing, looking at the ground for a moment in deep thought. I suddenly sprang to attention.

“I can call you Boxer!”

“Call me what you want,” the boy replied.

“No - really,” I replied with some jubilance. “I think that’s a great name.”

The lad moved behind me, and, turning to follow his direction, I swivelled on the orange box.

“You looked like a boxer when I first set eyes on you. I thought you must box for a boxing club of some sort.”

The boy looked at me sideways and then square in my face.

I started to look around the kiln.

“There’s smoke coming out of the chimney, Boxer. I couldn’t see where it was coming from when I looked around earlier.”

“That’s my little oven,” he said proudly. “I can just about make my bread.”

“Bread?”

“Yes, bread!” he replied sharply, glaring with his big blue eyes. “Me and little Smokey have to live on something - not like you city bods. You have it all done for you.”

“Who is little Smokey, Boxer?” By now I was beginning to get worried about the set-up there. Who was Boxer? Where did he come from? He looked a strange boy in his funny, old, dark, ragged clothes. And what about this Smokey geezer?

“Look over to the corner, and what do you see?”

He was smiling as we both looked together.

“Oooh,” I said, moving closer to what I could now see was a miniature table. There on one side was a miniature knife and fork, and on the opposite side was a larger knife and fork. I was gobsmacked, I can tell you.

“Tell me more, Boxer,” I said, moving closer to see better.

“Little Smokey is a mouse.” Boxer was standing beside me now. “He’s been my only friend in this place. He was nearly dead when I found him. He couldn’t fetch any food because his back legs were shot. Poor little mite just lay there - I had to help him.”

“What did you do, Boxer? How could you help him?”

“I found an old brown bottle which had a tube inside. ‘Eye-drops’ the bottle said. Anyway, I fed him with milk through the tube. I just gave him a tiny weeny drop at a time till he came through.”

“Gawd, that is wonderful.” I said, giving a few taps on Boxer’s shoulder in admiration.

“What about the knife and fork, though, Boxer?” I asked, picking them up to take a better look.

“I found an old broken saw blade and small file,” he said, picking up the miniatures and giving them a blow and a polish with an old hanky he had. “It took ages to make them.”

“They’re super-duper, Boxer - made so perfect, just like real ones.”

Just then, I heard a squeaking noise coming from the far corner of the kiln.

“Stand still and meet little Smokey,” said Boxer with his finger over his lips as a sign to hush.

He placed a few breadcrumbs on the spot where the miniature knife and fork were, and up the legs of the makeshift table ran the little white mouse. Stopping for a moment, he sat down on his back legs to have a good look around. His little pink nose quivered as he sniffed in all directions before going to his place between the knife and fork.

“Sometimes,” said Boxer as quietly as possible, “I can go right up to him and have a little natter before he decides to go.” Boxer smiled proudly.

We decided to go and sit down on the makeshift seats, leaving little Smokey to his supper of Boxer’s bread.

“How did you make the bread, then, Boxer?”

I thought the whole thing wonderful as he explained in detail his friendship with Smokey.

“I make for the cornfield over yonder,” he said, pointing towards the field, “then put the corn in this bowl here.” He lifted up an old metal bowl he had found in the corner. “Bash all the corn in the bowl till it turns to flour, blow away all of the ears, then mix it with water from that old tap outside.” I followed him over to a small oven in the corner of the kiln. “Then I place it inside this old oven over here till cooked - a nice brown colour, I might add.”

“What about yeast?”

“What’s yeast?”

“Oh, it doesn’t matter,” I replied.