Chapter 5: Understanding Solar Energy

Now that you know the most important things you need to do to prepare your home for a solar heating system, we can turn our attention to the source of energy you’ll be tapping: the Sun. In this chapter, I’ll explore the Sun and solar energy, providing you with the information you need to understand to get the most out of a solar home heating system.

Understanding Solar Radiation

The Sun lies in the center of our solar system, approximately 93 million miles from Earth. Composed primarily of hydrogen and small amounts of helium, the Sun is a massive fusion reactor. In the Sun’s core, intense pressure and heat force hydrogen atoms to unite, or fuse, creating slightly larger helium atoms. In this process, immense amounts of energy are released; this energy migrates to the surface of the Sun and then radiates out into space, primarily as light and heat.

A small portion of this light and heat streaming through space strikes the Earth, warming and lighting our planet, and fueling aquatic and terrestrial ecosystems. According to French energy expert, Jean-Marc Jancovici, “the solar energy received each year by the Earth is roughly … 10,000 times the total energy consumed by humanity.” To replace all the oil, coal, gas, and uranium currently used to power human society with solar energy, we’d need to capture a mere 0.01% of the energy of the sunlight striking Earth each day.

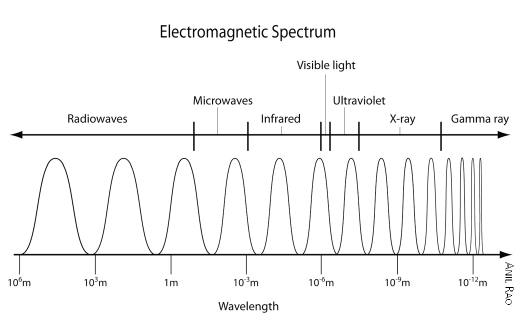

The Sun’s output is known as solar radiation. As shown in Figure 5-1, solar radiation ranges from high-energy, short-wavelength gamma rays to low-energy, long-wave radiation known as radio waves. In between these extremes, starting from the short-wave end of the spectrum are x-rays, ultraviolet radiation, visible light, and heat (infrared radiation).

While the Sun releases numerous forms of energy, most of it (about 40%) is infrared radiation (heat) and visible light (about 55%). Traveling at 186,000 miles per second, solar energy takes 8.3 minutes to make its 93 million mile journey from the Sun to the Earth. Solar radiation travels virtually unimpeded through space until it encounters Earth’s atmosphere. In the outer portion of the atmosphere (a region known as the stratosphere) ozone molecules (O3) absorb much (99%) of the incoming ultraviolet radiation, dramatically reducing our exposure to this potentially harmful form of solar radiation. As sunlight passes through the lower portion of the atmosphere (the troposphere), it encounters clouds, water vapor, and dust. These may either absorb some of the Sun’s rays or reflect them back into space, reducing the amount of sunlight striking Earth’s surface. Absorbed solar radiation in the visible range is converted into heat.

Solar heating systems — including passive solar homes, solar hot air systems, and solar hot water systems — capture the energy contained in the visible and lower end of the infrared portions of the spectrum, known as near-infrared radiation (Figure 5-1).

Fig. 5-1: The top bar shows the wavelengths of the different forms of radiation emitted by the Sun. The lower bar shows the visible and near-infrared portions of the spectrum — the portion that provides us with the energy we use to heat our homes. Much of the ultraviolet radiation is blocked by window glass.

Irradiance

The amount of solar radiation striking a square meter of Earth’s atmosphere or Earth’s surface is known as irradiance. It is measured in watts per square meter (W/m2). Solar irradiance measured just before it enters the Earth’s atmosphere is about 1,366 W/m2. On a clear day, nearly 30% of the Sun’s radiant energy is either absorbed and converted into heat or reflected by dust and water vapor back into outer space. By the time the incoming solar radiation reaches a solar collector on a roof, the incoming solar radiation is reduced to about 1,000 W/m2.

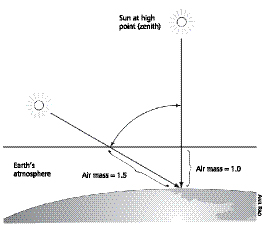

Solar irradiance varies during daylight hours at any given site. At night, solar irradiance is zero. As the Sun rises, irradiance increases, peaking around noon. From noon until sunset, irradiance slowly decreases, falling once again to zero at night. These changes in irradiance are determined by the angle of the Sun’s rays, which changes continuously as the Earth rotates on its axis. The angle at which the Sun’s rays strike Earth affects both the energy density (Figure 5-2) and the amount of atmosphere through which sunlight must travel to reach Earth’s surface (Figure 5-3). Both affect the daily output of solar heating systems.

Energy Density

As shown in Figure 5-2, low-angled sunlight delivers much less energy per square meter than high-angled sunlight. Low-angled sun thus has a lower energy density. The lower the density, the lower the irradiance. Early in the morning, then, irradiance is low. As the Sun makes its way across the sky, however, it beams down more directly onto Earth’s surface. This increases the energy density and irradiance. A passive solar home or solar collector installed for space heating will therefore gain more solar energy as the day progresses toward noon (and slightly after noon).

Fig. 5-2: Surfaces perpendicular to incoming solar radiation absorb more solar energy than surfaces not perpendicular. This has many important implications when it comes to mounting solar collectors.

Irradiance is also influenced by the amount of atmosphere through which the sunlight passes, as shown in Figure 5-3. The more atmosphere through which sunlight passes, the more filtering occurs. The more filtering, the less sunlight makes it to Earth. The less sunlight, the lower the irradiance. Solar space-heating systems must be oriented to capture as much sunlight as possible during this period of lowest irradiance — that is, during the heating season, when the Sun is low in the sky.

Fig. 5-3: Early and late in the day, sunlight passes through more atmosphere. This reduces irradiance. Maximum irradiance occurs when the Sun’s rays pass through the least amount of atmosphere, that is, at solar noon (halfway between sunrise and sunset). Three fourths of a solar space-heating system’s output occurs between 9 am and 3 pm each day.

Irradiation

Irradiance is an important measurement, but what most solar installers need to know is irradiance over time — that is, the amount of energy that will strike a solar collector or enter a passive solar home in a 24-hour period. Irradiance over a period of time is referred to as solar irradiation. It’s expressed as watts per square meter striking Earth’s surface (or a PV module) for some specified period of time — usually an hour or a day. Hourly irradiation is expressed as watt- hours per square meter. (Remember watt-hours and kilowatt-hours discussed in Chapter 2?) For example, solar radiation of 500 watts of solar energy striking a square meter for an hour is 500 watt-hours per square meter. Solar radiation of 1,000 watts per square meter over two hours is 2,000 watt-hours per square meter. To determine watt-hours, simply multiply watts per square meter by hours.

To help keep irradiance and irradiation straight, you can think of irradiance as a measure of instantaneous power (measured in watts). Irradiance is therefore a rate.

Irradiation, on the other hand, is a measure of power during some specified period of time and is, therefore, a measure of energy. It is a quantity.

Teachers help students keep the terms irradiance and irradiation straight by likening irradiance to the speed of a car. Like irradiance, speed is an instantaneous measurement. It simply tells us how fast a car is moving at a particular moment. Irradiation is akin to the distance a vehicle travels. Distance, of course, is determined by multiplying the speed of a vehicle by the time it travels at a given speed. In a car, the longer you travel, the greater the distance you’ll cover. In solar energy, irradiation increases with time.

Figure 5-4 illustrates the concepts graphically. In this diagram, irradiance is the single black line in the graph — the number of watts per square meter that strike a surface at any moment in time. The area under the curve is solar irradiation — the total solar irradiance over time. In this graph, it’s the irradiance occurring in a day. Solar irradiation is useful in sizing all types of solar systems.

Fig. 5-4: This graph shows solar irradiation, watts per square meter, and irradiation in watts per square meter in a day. Irradiation is the area under the curve.

The Sun and the Earth:Understanding the Relationships

Now that you understand irradiance and irradiation, let’s examine the geometric relationships between the Earth and Sun. An understanding of the ever-changing relationship between the Earth and the Sun helps you understand how passive solar systems work and the best position (orientation and angle) for a solar hot water or solar hot air collector.

Day Length and Altitude Angle:The Earth’s Tilt and Orbit Around the Sun

As you learned in grade school, the Earth orbits around the Sun, completing its path every 365 days (Figure 5-5).

As shown in Figure 5-6, the Earth’s axis is tilted 23.5°. The Earth maintains this angle as it orbits around the Sun. Look carefully at Figure 5-5 to see that the angle remains fixed —almost as if Earth were attached to a wire attached to a fixed point in outer space. Because Earth’s tilt remains constant, the Northern Hemisphere is tilted away from the Sun during its winter (Figure 5-5). As a result, the Sun’s rays enter and pass through Earth’s atmosphere at a very low angle. Sunlight penetrating at a low angle passes through more atmosphere, where it is absorbed or scattered by dust and water vapor, as shown in Figure 5-3. This, in turn, reduces irradiance, reducing solar gain by all solar systems.

Fig. 5-5: Note that Earth is closest to the Sun in the winter in the Northern Hemisphere, but the Northern Hemisphere is tilted away from the Sun, so the Sun’s rays penetrate the atmosphere at a low angle.

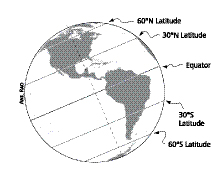

Irradiance is also lowered because the density of sunlight striking Earth’s surface is reduced when it strikes a surface at an angle. As shown in Figure 5-2, a surface perpendicular to the Sun’s rays absorbs more solar energy than one that’s tilted away from it. As a result, low-angled winter sunlight delivers much less energy per square meter of surface in the winter than it does during summer. During the winter in the Northern Hemisphere, most of the Sun’s rays fall on the Southern Hemisphere.

Solar gain is also reduced in the winter because days are shorter — that is, there are fewer hours of daylight. Day length is determined by the angle of the Earth in relation to the Sun.

Fig. 5-6: The Earth is tilted on its axis of rotation, a simple fact with profound implications.

In the summer in the Northern Hemisphere, the Earth is tilted toward the Sun, as shown in Figures 5-5 and 5-7. This results in several key changes. One of them is that the Sun is positioned higher in the sky. As a result, sunlight streaming onto the Northern Hemisphere passes through less atmosphere, which reduces absorption and scattering. This, in turn, increases solar irradiance. Because a surface perpendicular to the Sun’s rays absorbs more solar energy than one that’s tilted away from it, the Northern Hemisphere intercepts more energy during the summer. Put another way, high-angled Sun delivers much more energy per square meter of surface area than in the winter. Moreover, days are longer in the summer.

Fig. 5-7: Note that during the summer, the Northern Hemisphere is bathed in sunlight. The Sun’s rays enter at a steep angle. In the winter, the Sun’s rays enter at a low angle.

Keep these facts in mind as you read about the three solar home heating options I’ll be covering: passive solar, solar hot air, and solar hot water. They’re crucial concepts one must know to optimize the performance of each system.

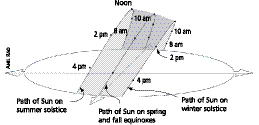

Figure 5-8 shows the position of the Sun as it “moves” across the sky during different times of the year as a result of the changing relationship between the Earth and the Sun. As just discussed, the Sun “carves” a high path across the summer sky. It reaches its highest arc on June 21, the longest day of the year, also known as the summer solstice. Figure 5-8 also shows that the lowest arc occurs on December 21, the shortest day of the year. This is the winter solstice.

Fig. 5-8: This drawing shows the path of the Sun across the sky during the year. Solar hot water systems are designed to capture solar energy throughout the year because they produce both hot water and solar space-heating. Solar hot air collectors and passive solar homes are designed to capture sunlight energy only during the heating season — late fall, winter, and early spring.

For curious readers, the English word solstice comes from the Latin solstitum, which comes from sol for Sun and ìsunî and -stitium, meaning a stoppage. The summer and winter solstices are those days when the Sun halts its upward and downward “journey.”

The angle between the Sun and the horizon at any time during the day is referred to as the altitude angle. As shown in Figure 5-8, the altitude angle decreases from the summer solstice to the winter solstice. After the winter solstice, however, the altitude angle increases, growing a little each day, until the summer solstice returns. Day length changes along with altitude angle, decreasing for six months from the summer solstice to the winter solstice, then increasing until the summer solstice arrives once again.

The midpoints in the six-month cycles between the summer and winter solstices are known as equinoxes. The word equinox is derived from the Latin words aequus (equal) and nox (night). On the equinoxes, the hours of daylight are nearly equal to the hours of darkness. The spring equinox occurs around March 20, and the fall equinox occurs around September 22. These dates mark the beginning of spring and fall, respectively.

As just noted, the altitude angle of the Sun is determined seasonally by the angle of the Earth in relation to the Sun. The altitude angle is also determined daily by the rotation of the Earth on its axis. As seen in Figure 5-8, the altitude angle increases between sunrise and noon, then decreases to zero once again at sunset.

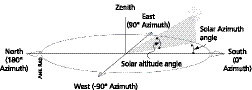

The Sun’s position in the sky relative to a fixed point, such as a solar hot water system collector, also changes by the minute. Solar installers locate the Sun’s position in the sky in relation to a fixed point by using the azimuth angle. As illustrated in Figure 5-9, true south is assigned a value of 0°. East is +90° and west is -90°. North is 180°. The angle between the Sun and 0° south (the reference point) is known as the solar azimuth angle. If the Sun is east of south, the azimuth angle falls in the range of 0 to +180°; if it is west of south, it falls between 0 and -180°. Like altitude angle, azimuth angle changes as a result of the Earth’s rotation.