Chapter 6: Passive Solar Heating: Low-Tech, High Performance

Each day, the low-angled winter sun heats millions of buildings in the Northern Hemisphere. Streaming in through south-facing windows, the Sun’s rays warm the interiors of homes and offices. Most of this solar heating is not intentional, however. That is, most of these homes are not designed to capture the Sun’s energy. It just happens. Their south-facing windows simply allow solar energy from the low-angled winter sun to pass through them (provided the windows are not covered by curtains or blinds).

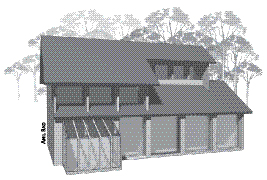

Among the legions of accidentally solar-heated homes are many intelligently designed and carefully oriented homes that intentionally capture solar energy to provide wintertime heat (Figure 6-1). These are known as passive solar homes. “Passive” refers to the fact that these buildings do not require complicated or costly mechanical systems to generate and distribute heat (though they may be needed for backup heat). A passive solar home is as low-tech as you can get. They’re inexpensive to build and easy to operate.

Fig. 6-1: This home designed by James Plagmann of HumaNature Architecture and me allows the low-angled winter sun to enter through south-facing windows.

This chapter discusses the design and construction of a passive solar home — actually any building that is heated by the Sun. These ideas generally apply to new construction. If you are retrofitting a house for passive solar, the next chapter discusses ways you can do that. Be sure to read this chapter first, however, as it provides important concepts you’ll need to know.

Passive solar design can save you thousands of dollars a year — and tens, even hundreds, of thousands of dollars — over a period of 20 to 30 years. The savings to the owner are substantial enough to pay for a child’s four-year college education!

In the following sections, I’ll introduce the basic principles of passive solar design. I will then discuss how these principles are used to create passive solar buildings.

Principles of Passive Solar Heating

Passive solar heating relies on a handful of time-tested design principles to ensure its success. Study them carefully, implement them in your building design, and you’ll be rewarded with a lifetime of free heat.

Orient to True South

First and foremost, a passive solar home must be oriented to true south (in the Northern Hemisphere). What that means is that the long axis of the home runs from east to west. This results in a rather large south-facing surface in which windows can be installed to permit the low-angled winter sun to enter.

A solar home should be oriented to true south, not magnetic south. As noted in the last chapter, true north and south are the lines of longitude that run from the North Pole to the South Pole. Magnetic south is detected by a compass, but rarely corresponds to true south.

In fact, as you can see in Figure 6-2, magnetic lines deviate substantially from true north and south. This phenomenon, discussed in Chapter 5, is referred to as magnetic declination. As illustrated, the only place where magnetic south and true south correspond in North America is near the very center of the Continent. At our educational center in east-central Missouri, for instance, magnetic south is only about one degree off from true south. Travel to St. Louis, about 70 miles east of our campus, and you’ll find that magnetic and true south line up perfectly.

Fig. 6-2: This map shows the difference between magnetic and true south.

As shown in Figure 6-2, magnetic declination west of the “zero line,” which runs through the center of the Continent, increases. If you were to design a passive solar home in east-central Kansas, the compass reading would be 5° off. Colorado would be about 10° off. But which way? Is true south east or west of magnetic south?

When designing a passive solar home located in a site west of the “zero line,” true south lies east of magnetic south. In a site in Kansas, then, magnetic south would be 5° east of magnetic south. In eastern Wyoming, central Colorado, or north central New Mexico, true south would about 10° east of magnetic south. (Take a look at the line in Figure 6-2 to confirm this assertion.) If you were siting a home in western Montana or eastern Idaho, true south would be 15° east of magnetic south.

East of the “zero line,” magnetic declination is westerly. If you are siting a home in central Florida, for instance, true south would be 5° west of magnetic south. In western Pennsylvania, true south would be 10° west of magnetic south.

Don’t forget to adjust for magnetic declination! If this detail slips your mind, your passive home will collect a lot less sunlight energy in the winter and too much in the summer, causing overheating. The goal, once again, is to orient a solar home as close to true south as possible to maximize solar gain.

Concentrate Windows on the South

Passive solar homes and businesses are really large, building-sized solar collectors. They are designed to capture the Sun’s energy and turn it into heat. Like other types of solar collectors, solar homes require a transparent surface to allow sunlight in. In the case of a solar home, the transparent surfaces are the south-facing windows. Sunlight streams through this glass (called solar glazing), warming the interior.

To ensure maximum solar gain, windows in a passive solar home are concentrated along the southern wall, where they’ll do the most good on a cold winter day. My rule of thumb is that the square footage of solar glazing should be equal to 12% to 15% of the square footage of the building (for a one-story building with a conventional ceiling height of eight or nine feet). Higher levels may be required to increase solar gain. Remember that window surface area is only the area occupied by glass, not the frames of windows. To determine the square footage of glass, designers typically multiply the window dimensions to determine total square footage, then deduct 25% to take the framing into account.

To minimize heat loss, north-facing windows should be limited to no more than 4% of the total square footage. East-facing windows are limited to 4% of the square footage of the building, and west-facing windows are limited to 2% to reduce heat gain in the summer. As an example, a 1,000-square-foot single-story building would require 120–150 square feet of south-facing glass, but no more than 40 square feet of north- and east-facing glass, and no more than 20 square feet of west-facing glass.

These rules are general design guidelines for the ideal passive solar home. Most designs violate these rules for one reason or another. If a home faces a beautiful lake on the west side, for example, an owner might want to install a few more windows on that side to take in the view. To prevent overheating, however, the owner would need to install special glass to reduce heat gain in the summer through the west-facing windows. This glass needed for these windows is known as low solar heat gain coefficient (SHGC) glass.

Create an Airtight, Energy-Efficient Building

Another key to successful passive solar design is to design and construct buildings that are airtight and superinsulated. As you learned in Chapters 3 and 4, these measures help retain heat inside a home. Because solar energy is a rather diffuse (low-concentration) form of energy, you have to use every trick in the book to gather up and retain solar heat. There’s no sense letting that hard-won solar energy escape through a leaky, poorly insulated building envelope.

For more on airtight energy-efficient design, be sure to read Chapters 3 and 4, if you haven’t already done so. If you want to learn more about insulation and air sealing, look at my book, Green Home Improvement or The Solar House: Passive Heating and Cooling. The latter provides detailed coverage of this topic. (For those who speak Chinese, there’s now a Chinese edition!)

Incorporate Thermal Mass

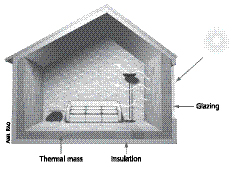

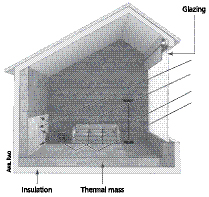

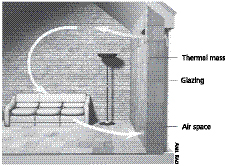

Passive solar buildings absorb sunlight during daylight hours. This heat warms the interiors, providing comfort. To heat a building at night, designers incorporate thermal mass in their buildings (Figure 6-3). Thermal mass consists of any solid masonry-type material that absorbs heat. It acts like a heat sponge, absorbing warmth during the day, then releasing it at night or on cold, cloudy days. Concrete and tile floors in solar homes and brick or stone-faced interior partition walls strategically located in a passive solar home can often be employed as thermal mass — if properly placed. They’ll release heat at night and on cloudy days if they’ve been charged by the Sun.

Fig. 6-3: This diagram shows thermal mass in a passive solar home that absorbs heat during the day, releasing it at night or on cloudy days.

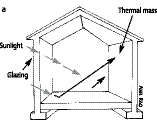

Thermal mass is generally dark-colored mass, a feature that increases its absorption capacity — but not so dark as to create hot spots. Thermal mass should be about four inches thick for optimum performance and is best located so it is directly in the path of the incoming solar radiation (Figure 6-4). This usually means that most of the thermal mass should be located on the south side of the home’s interior, near the solar glazing.

Fig. 6-4: a-c This drawing shows the optimum placement of thermal mass in the direct path of incoming solar radiation. Thermal mass located in the back walls is also vital to achieving maximum comfort.

For maximum comfort, however, thermal mass should surround the living space. That way, heat absorbed during the day will radiate from all interior wall surfaces at night, making rooms feel warmer. (Comfort is determined not just by air temperature but also by mean surface temperature of the walls — that is, the temperature of the interior wall surfaces. The warmer they are, the warmer a person will feel.)

Provide Adequate Overhang

Passive solar homes typically incorporate overhangs or eaves, at the very least, on the south side of the building. (Overhangs are a good idea in any building because they shade windows and walls in the summer and reduce the amount of rain dripping down walls.)

Overhangs shade the solar glazing in late spring, summer, and early fall, preventing buildings from overheating. Generally, passive solar homes require a two- to three-foot overhang to protect against the summer sun.

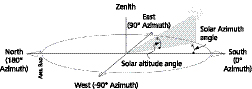

Overhangs not only protect a home from the high-angled summer sun, they are the on-off switches of passive solar homes. The overhang determines when the Sun begins to “peek” into the windows in the fall, and when it can no longer gain access in the spring. As you may recall from Chapter 5, the Sun’s path changes throughout the year from a high point in June to the low point in December (Figure 6-5). The length of the overhang determines when the Sun’s rays can enter a building.

Fig. 6-5: The Sun’s position in the sky changes throughout the year, as illustrated here. It is lowest in the winter, which is ideally suited for passive solar heating.

Passive Solar Design Options

Passive solar can be incorporated into almost any building. Even if the long axis is oriented north and south instead of east and west, windows can be placed in the south-facing walls to capture the low-angled winter sun. For the best year-round results, however, a passive solar building should be oriented to true south. Improper orientation, like orienting the long axis of a building from north to south will increase solar gain in the summer — often dramatically — which results in massive unwanted heat gain. This, in turn, results in considerable discomfort and high cooling costs. In addition, the wrong orientation dramatically reduces the potential for solar heating.

Direct Gain

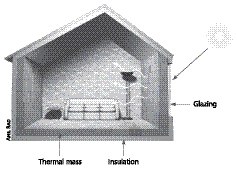

When it comes to designing a passive solar building, you have three options. The first is direct gain. As shown in Figure 6-6a, direct gain is the simplest of all passive solar design options. The building becomes a huge solar collector. South-facing windows on the building allow the Sun’s rays to enter, heating the home directly, hence its name.

Direct gain is not only the simplest passive solar design option, it is also arguably the most efficient and cost effective, for reasons that will become clear shortly.

For best results, be sure to install thick, insulated window shades or curtains over all windows — especially the solar glazing — to hold heat in at night. At night, solar glazing can get quite cold. If it isn’t covered, people sitting near the windows on cold winter nights will feel quite cold.

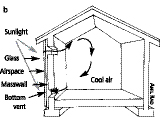

Isolated Gain — Attached Sunspaces

Another option for passive solar gain is referred to as isolated gain, and is shown in Figure 6-6b. Isolated gain, also referred to as attached sunspaces, is great for retrofits (discussed in more depth in Chapter 7). Located on the south side of homes, attached sunspaces act as solar collectors. Solar-heated air warms the sunspace and, if it’s designed properly, the adjoining rooms. In this design, then, sunlight is absorbed in a separate, or isolated, space, then transferred to the main living spaces — hence the name “isolated gain.”

Attached sunspaces can be incorporated in new building designs, but they tend to increase the cost of a building. Direct gain is far cheaper when building anew. Attached sunspaces need to be designed very carefully to achieve one’s goals. All-glass sunspaces, for instance, have a nasty habit of overheating, indeed baking, in the hot summer sun. They can even bake occupants on cold, but sunny, winter days, making the spaces virtually uninhabitable when the Sun’s shining in. They also tend to get very cold at night in winter, so they need to be closed off from the main living space to prevent it from cooling down. If you are considering this option, be sure to consult an experienced and accomplished solar designer.

Fig. 6-6 a–b: (a) In a direct gain passive solar building, sunlight enters the building through solar glazing, heating it directly. Thermal mass located in the direct path of incoming solar radiation is vital to achieving maximum comfort. Thermal mass can be located in floors and walls as shown here. (b) Isolated gain — attached sunspace.

Indirect Gain — Trombe Walls

The third option for passive solar is indirect gain. As shown in Figure 6-6c, indirect gain involves the installation of a large mass wall immediately behind windows on the south side of a building. The windows are typically two to six inches from the mass wall, no more.

Fig. 6-6 c: Indirect gain — Trombe wall.

Walls built for indirect gain are also known as thermal storage walls or Trombe walls (pronounced “trom”). Thermal storage walls are warmed by the incoming solar radiation. Heat generated in the walls migrates inward by conduction (moving from hot to cold) during the day. By the time the Sun sets, the heat has migrated to the interior of the wall. It then radiates into the adjoining rooms, warming them. Because the mass wall heats first, and because this heat is then transferred to adjoining rooms, this design is referred to as indirect gain.

Trombe walls are the invention of a French engineer by the same name. They work extremely well in all climate zones — if designed and constructed properly. (In many cases, though, they’re poorly designed and fail miserably!)

Thermal storage walls provide delayed solar gain. That is, they heat up during the day, then transfer that heat to the adjoining rooms after the Sun sets. For immediate gain, windows can be installed in the thermal mass wall, allowing sunlight to penetrate directly into the room. In addition, vents can be installed in the upper and lower portions of the wall, as shown in Figure 6-7. The vents allow room air to circulate through the space between the thermal storage wall and the glass. Sunlight warms the air, causing it to expand. As air expands, it becomes lighter. The lighter, warm air rises, then pours into the room. This creates a thermosiphon, a force that pulls cooler floor-level air through the lower vent. This cooler air is then heated by solar radiation. As long as the Sun shines, this thermal convection loop continues to circulate air from the room to the airspace between window and Trombe wall where it is heated, then back into the room. Vents can be either manually or automatically shut at night to prevent reverse air movement at night, which would cool the room down. (At night, air between the mass wall and the glass cools and sinks, and could enter the room through open lower vents. This would draw warm room air through vents at the top of the wall, where it would be cooled.)

Fig. 6-7: Heat given off by the thermal storage wall radiates into the room keeping it warm at night. A window placed in this wall would permits day lighting and daytime solar gain. Vents shown here also permit daytime heating.

Indirect gain is the rarest of all passive solar options. It has a bad reputation in the solar industry, but my experience is that it works well — actually, it works extremely well — if it is designed correctly. I’ve inspected several homes in which it wasn’t working, and in each case the homeowner had made an egregious mistake by installing sheet rock over the inside surface of the mass wall, screwing it onto furring strips. The layer of drywall blocks heat flow from the mass wall into the interior.

Thermal storage walls require heftier foundations to support their weight, so plan accordingly. If designed and built correctly, though, they should provide years of maintenance-free comfort. They’re especially well suited to home offices occupied during daylight hours. The mass walls block out much of the incoming solar radiation, preventing overheating and glare on computer screens. They’re also great in bedrooms for people who like to sleep in dark rooms at night. If dark window shades are installed, the room can be made extremely dark.

Next Steps

Passive solar homes incorporate these design ideas that allow them to collect and store solar energy to heat homes during the day and night — and during cloudy periods. There is much more to passive solar design than I’ve covered here, but this provides the basics. I urge readers to study the topic in more detail either by attending workshops on passive solar design (like those I offer through The Evergreen Institute) or by reading more books and articles on the subject. Further study will help you better appreciate this design strategy. You may also want to take a look at my book, The Solar House: Passive Heating and Cooling. It is written for the general reader — you don’t have to be an engineer to understand the material.

Conclusion

Passive solar can be incorporated into any building design. No matter what your tastes are, you can easily incorporate passive solar, creating a home that is attractive and very economical to live in.

Passive solar heating is an intelligent choice in building design. It provides free heat — often an amazing amount of free heat — for the life of a building, which could potentially save owners hundreds of thousands of dollars in fuel bills. How much heat you can obtain from the Sun depends on the amount of sunshine available in your area and your attention to the principles of passive solar design, especially proper orientation, window placement, quality of windows, air sealing, and insulation. The more faithfully you follow the design guidelines, the greater your solar gain.

Even in the least sunny climates in the United States, it’s possible to obtain 40% to 50% of your heat from the Sun. In sunnier climates, with careful design, 80% is a reasonable goal. Such efforts will not only help you save money, they’ll help you dramatically reduce your carbon footprint.

Passive design also ensures a much cooler home in the summer. Proper orientation, window allocation, air sealing, insulation, overhang, and thermal mass — all key principles of passive solar design — also help keep a home much cooler during the dog days of summer. Dollars or Euros invested in passive solar therefore pay double dividends.

It typically costs nothing more, or at best only a tiny bit more, to build a superefficient passive solar home that stays warm in the winter and cool in the summer. The question isn’t “Why should you build a passive solar home?” but “Why wouldn’t you?”