Chapter 10: Energy-Efficient Backup Heat

The goal of this book is to familiarize readers who want to increase their reliance on solar energy for heating with their options, to even help readers find ways to utilize the Sun’s energy to produce nearly 100% of the heat they need for their homes or businesses. Although your home or business can be heated entirely by clean, renewable solar energy, it’s easier to achieve this goal when starting from scratch. When retrofitting a building, your options are limited, and heating the building entirely with solar energy is much more difficult. In such cases, you’ll likely need a backup heating system.

If you are retrofitting an existing building with solar, your existing heating system could become your backup heat source — playing second fiddle to the energy-efficiency measures you incorporate and the passive solar, solar hot air, or solar hot water system you install. If your heater is old and inefficient and therefore in need of replacement, you may want to consider installing a new, more energy-efficient unit.

If you are building a new energy-efficient solar home from scratch, you’ll want to install an energy-efficient backup system — if for no other reason than to comply with the local building code. Building codes require backup heating to prevent pipes from freezing.

This chapter explores energy-efficient backup heating system options for new and existing homes, including energy-efficient furnaces and boilers.

Home Heating Basics

The vast majority of homes in North America are heated by the combustion of fossil fuels — natural gas, propane, or fuel oil — or by electricity, which, of course, is generated by coal-fired power plants, natural gas plants, or nuclear power plants. The vast majority of homes in North America are equipped with forced-air heating systems. They’re the least expensive of all mechanical heating systems to install, hence their popularity. Unfortunately, they tend to be the least efficient of all your choices.

Conventional (Low-Efficiency) Furnaces

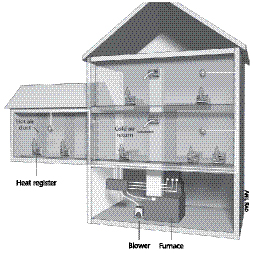

In forced-air heating systems, hot air produced by the furnace is distributed through the home by a large fan, known as a blower. The blower propels the heated air through an extensive duct system that supplies heated air to each room (Figure 10-1). Cool room air then returns to the furnace for reheating by a separate set of ducts, known as the cold air return ducts. (Ducts in forced-air systems are notoriously leaky, so it is a good idea to have yours tested and seal the leaks with mastic, a white gooey paste that provides the best, and longest-lasting seal.)

Fig. 10-1: Heat generated by the furnace is distributed through a duct system.

Furnaces are usually installed in a basement, or less commonly in a utility room or a well-vented closet. Gas furnaces contain a combustion chamber where natural gas or propane is burned. The burner may be ignited by a pilot light, a small flame that burns 24 hours a day, or by an electronic ignition, which provides a spark to ignite the fuel when heat is required. (The latter is more efficient.)

In a conventional furnace, referred to as a natural-draft furnace, heat produced inside the combustion chamber is transferred to cool air flowing over its heat exchanger. The blower propels the newly heated air through the supply ducts to the rooms. Cool air then flows back to the furnace through the return duct system.

Combustion gases that contain potentially lethal pollutants are vented from the combustion chamber to the outdoors through a flue pipe. As the hot gases rise, they create a partial vacuum in the combustion chamber. This draws room air into the fire, ensuring a continuous supply of the oxygen needed for proper combustion. The rise of hot air through the flue, together with the inflow of room air, is known as draft. (Draft is created by convection.)

Conventional natural-draft furnaces have been the mainstay of the heating industry for decades, but they are the least efficient of all furnaces on the market. Those manufactured before 1992 have efficiencies below 78%. Many old furnaces are only 55% to 65% efficient. Translated, that means that they convert only 55% to 65% of the fuel they burn into heat. The rest is wasted. If you were buying bananas at the same efficiency, you’d buy ten, then throw five and a half to six and a half away as soon as you got home.

High-Efficiency Furnaces

Fortunately, numerous manufacturers now produce high-efficiency furnaces for use with forced-air heating systems (Figure 10-2). The higher the efficiency, the more heat you get per unit of fuel that’s burned in the furnace. High-efficiency furnaces not only produce and deliver a lot more heat from the fuel they burn than older models, they save an enormous amount of money over the long-term.

Fig. 10-2:High-Efficiency Furnace.

Most high-efficiency gas furnaces are referred to as induced-draft models. That means that they contain a low-wattage electric fan that draws air from outside the home into the combustion chamber — rather than drawing air “naturally” from inside the home, as in older, natural-draft furnaces. The fan also propels exhaust gases from the combustion chamber out of the house via the flue pipe.

Induced-draft furnaces are equipped with more efficient heat exchangers and electronic ignitions, which eliminate the need for a standing pilot light. Both devices increase operating efficiency. Many high-efficiency furnaces contain controls that allow the blower to continue to blow hot air over the heat exchanger after the thermostat shuts the furnace down. This enables the blower to strip more heat from the heat exchanger and internal components of the furnace, increasing the efficiency of the furnace even more.

The most efficient gas furnaces on the market today are known as condensing furnaces. These furnaces contain a second heat exchanger that extracts heat from the exhaust gases — heat that would normally be lost as it escapes through the flue. By extracting heat from these gases, the heat exchanger cools the gases until the moisture (water) contained in the gases condenses. The condensation of water vapor from air also — almost mysteriously — releases heat. Condensing furnaces capture this heat as well and distribute it throughout the building as needed. Because so much heat is removed by the heat exchangers in condensing furnaces, waste gases can be vented through plastic pipe. When the furnace is operating, the flue pipe is barely warm to the touch. The moisture removed from the exhaust gases, however, must be drained into a nearby floor drain.

Both condensing and non-condensing furnaces are equipped with sealed combustion chambers. This feature prevents dangerous exhaust gases, such as carbon monoxide and nitrogen dioxide, from entering room air. Installing an energy-efficient furnace or replacing an old gas furnace with a superefficient model, therefore, will not only save you money, it could improve indoor air quality in your home.

When shopping for a new furnace, contact local installers for advice. If they’re reputable, they’ll tell you which models are the most efficient and reliable. You can also look on the Energy Star website for Energy Star-qualified models. An Energy Star label on a furnace ensures that it is among the most efficient on the market. Still, shop carefully. Among this elite group of furnaces you can still find considerable variation in energy efficiency. In other words, some Energy Star furnaces are a lot more efficient than others.

Furnace efficiencies are listed as annual fuel utilization efficiency, or AFUE, for short. They range from 83% to 99%. As a rule, the induced-draft furnaces have efficiencies in the 80% range, and induced-draft condensing furnaces are higher — in the 90% range — with some as high as 99%. Be wary of brand new models. It’s best to install a furnace that’s been on the market for at least four or five years — just to be sure that the bugs, if any, have been worked out. Check out the warranty very carefully. Deal with a company that’s been in the business for at least five years, preferably more.

To view a list of Energy Star-qualified furnaces, visit the Energy Star website (www.energystar.gov), and click on “Products,” then “Heating and Cooling,” and “Furnaces.” Be sure to check out the product lists.

If you can’t afford a new furnace, you should consider modifying your existing furnace to improve its efficiency. To learn how, read the Department of Energy’s Consumer’s Guide at their Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy website at: www.eere.energy.gov/.

High-Efficiency Oil Furnaces

Fuel oil is one of many products extracted from crude oil or petroleum. Fuel oil is not anywhere near as thick as crude oil. It’s more like diesel fuel.

Fuel oil is burned in furnaces in many parts of the United States — notably the Northeast, the Northwest, and the central states. Fuel oil is injected into the furnace’s combustion chamber through a nozzle that produces a fine spray of tiny droplets.

If you have an oil furnace manufactured prior to 1992, chances are it’s quite inefficient — possibly only 50% to 60% efficient. In contrast, newer Energy Star-qualified oil furnaces have efficiencies in the 83% to 86% range. Even more efficient are condensing oil furnaces, which are about 95% efficient. Although condensing models are more efficient, they’re not very common and are often not recommended, mainly because fuel oil contains many chemical contaminants (such as sulfur) — far more than are found in natural gas or propane. These contaminants condense out and produce a fairly corrosive liquid that can damage the internal components of a furnace.

Although sealed combustion chambers are common in high-efficiency gas furnaces, very few high-efficiency oil furnaces come with this feature. The reason is that cold outside air drawn into the combustion chamber in an oil furnace reduces combustion efficiency. It can also impair ignition.

Because oil furnaces are not usually equipped with sealed combustion chambers, carbon monoxide can leak into room air. Carbon monoxide is a colorless, odorless, poisonous gas that can kill people and animals when present in high concentrations. It is therefore a good idea to install a carbon monoxide detector or two if you heat with an oil furnace. One detector is recommended for every floor, in a location where they can be heard, especially near the master bedroom. Check building code requirements to be certain you have the right number and they’re in the correct location.

Conventional Boilers andHydronic Heating Systems

If your home is heated by a radiant floor or baseboard hot water system, heat is generated by a boiler (so named because it boils water). The heated water is then circulated through pipes, supplying heat to in-floor, baseboard hot water, or other types of radiators (heat exchangers). These systems are referred to as hydronic heating systems.

Boilers are typically located in basements or utility rooms, just like furnaces. Also like furnaces, they typically burn natural gas, propane, or heating oil. The combustion of fossil fuels in a boiler heats water that is circulated in pipes surrounding the combustion chamber. In some cases, electricity is used to generate heat, although electric heat can be quite expensive.

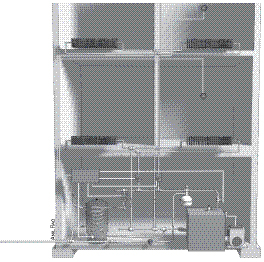

In homes with radiant floor systems, also known as in-floor heating, hot water generated by the boiler is pumped through pipes beneath the finished floor — either in a concrete slab or under wood flooring or tile (Figure 10-3). Heat is released and absorbed by the floor, which warms up, radiating heat into the rooms.

Fig. 10-3: Radiant Floor Heating System.

In homes equipped with baseboard hot water systems, water is circulated throughout the house to baseboard radiators. These devices are heat exchangers that release heat into the rooms in which they are located (Figure 10-4). Installed along the base of walls, they contain a series of aluminum fins attached to a copper pipe that runs the length of the unit. Heat flowing through the copper pipe flows into the fins, which dramatically increase the surface area for heat exchange. The heat then radiates into the rooms. The fins also heat the air above them. Air heated by the fins expands, becomes lighter, then rises, moving via convection through the rooms of a house.

Fig. 10-4: Baseboard Hot Water System.

In-floor and baseboard heating systems are inherently more efficient than forced hot air systems and therefore more cost effective. Their efficiency stems from the fact that forced-air heating systems tend to pressurize the interior of buildings, that is, increase pressure due to the flow of hot air into rooms via the duct system. Pressuring the interior forces air out through tiny leaks in the building envelope.

Energy-Efficient Boilers

If you are building a new home or considering upgrading your existing boiler, be sure to study the many energy-efficient boilers now on the market. Most modern boilers can achieve combustion efficiencies in the 85% to 90% range. Some are as high as 92% to 95%.

If you can’t afford a new boiler, you may want to consider an efficiency upgrade for your existing boiler. You can learn more about upgrades by reading DOE’s Consumer’s Guide on their Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy website at www.eere.energy.gov.) Your first upgrade, however, should be insulating the pipe that distributes the heat.

In an effort to boost the efficiency of a gas-fired boiler, manufacturers now typically include an electronic ignition, eliminating the standing pilot light. Electronic ignitions produce a spark that ignites the burner when heat is required. High-efficiency boilers are also designed to burn fuels more efficiently and extract more heat from combustion gases. These features mean more heat per BTU of fuel burned.

Like energy-efficient furnaces, energy-efficient boilers come with sealed combustion chambers where gas or oil burns. Replacement air comes from the outdoors, not from room air. A small fan draws air into the combustion chamber and forces the exhaust gas out through the flue. (These are known as induced-draft boilers.) This design reduces the amount of dangerous — and potentially lethal — pollutants entering a building. Sealed combustion chambers also reduce the amount of air infiltration through leaks in the building envelope. This natural influx replaces air lost through the flue. (As room air enters the combustion chamber of a furnace or boiler and then escapes through the flue with combustion waste products, it depressurizes a building. Outside air is then drawn into the home to replace air lost through the flue.) Sealed combustion chambers reduce air leakage through the building envelope that occurs with natural draft furnaces.

To check out your options, call several local HVAC professionals for recommendations; obtain their literature, and study it carefully. I recommend buying high-efficiency models that have been on the market for a while, and hiring installers who have been in the business for a while, too. Check the Better Business Bureau for complaints. Hire an installer who has a proven track record — with high customer satisfaction — and who provides a good warranty on the furnace and his or her work. To learn more about your options, check out Energy Star’s website (www.energystar.gov). Click on “Heating and Cooling” under products, then click on “Boilers” for a consumer product list. This site contains an enormous amount of information and can be confusing at first, so take your time. Study your options very carefully. Take notes. Learn as much as you can before you contact an installer, so you know what they are talking about.

Shopping for a New Furnace or Boiler

When shopping for an energy-efficient furnace or boiler, remember that quality costs more. You may end up paying $500 to $1,000 more for a high-efficiency model. However, that investment could save you a substantial amount of money over the long-term. You can usually offset the higher initial cost within a few years through lower heat bills. After this period, the savings from a new furnace essentially becomes a source of income.

Remember, too, that the higher upfront investment also provides a hedge against rising fuel costs. To calculate your cost savings, you can use the Savings Calculator on the Energy Star website. You can also calculate the return on investment via the cost calculator on the website of the American Council for an Energy-Efficient Economy (www.aceee.org).

When considering a new energy-efficient furnace or boiler, be sure to look into state and local tax incentives or rebates from local utilities. Many incentives are available to homeowners that will help reduce the higher initial cost of a more efficient furnace. To check out incentives in your area, call your utility or the state energy office or ask local installers. You can also find information on the Database on State Incentives for Renewables and Efficiency at www.dsireusa.org. Installers should be able to provide information on incentives, but always check with other sources or even an accountant to be sure you’ve got it right.

When buying a new furnace or boiler, be sure that the system is properly sized to your home, especially if you have retrofitted your home for energy efficiency. HVAC contractors have a tendency to oversize furnaces and boilers. According to the DOE, heating systems in new American homes are often two or three times larger than required.

Unfortunately, oversized furnaces and boilers cycle on and off more frequently than properly sized systems. This, in turn, results in less-efficient operation. (It takes a little time for a furnace to reach maximum efficiency, so if it is cycling on and off, it runs at peak efficiency less often.) Start-ups also require more fuel. All of these factors result in more fuel consumption — which may offset efficiency gains. As a rule, a heating system should be no more than 25% larger than the calculated heat requirement.

Be sure to hire a highly reputable HVAC contractor — one who is capable of installing the equipment and doing a good job, but also of accurately calculating your heat demand. Be sure they take into account energy-efficiency measures you’ve incorporated, especially weatherization efforts and your solar system. After your new boiler or furnace is in place, be sure to follow maintenance recommendations and hire a professional to periodically inspect and maintain your system.

Call several reliable installers in your area to see what kinds of systems they offer, and what they recommend. You can find a contractor by searching the Yellow Pages or, better yet, ask a general contractor you trust for recommendations.

What about a Heat Pump for Backup?

With growing awareness of the dangers of global warming and the continually rising cost of home heating fuels, many people are considering heat pumps — sometimes as a backup to solar heating options. As you shop, you will find two choices: ground-source and air-source heat pumps.

Heat pumps are devices that use refrigeration technology to extract heat from the environment. Extracted heat is then transferred into a building.

Heat pumps can remove heat from the air surrounding a building — an air-source heat pump — or from the ground — a ground-source heat pump. Ground-source heat pumps are typically referred to as geothermal systems (Figure 10-5). Heat extracted from the air or the ground is distributed through a building either through ducts in a forced-air system, or through pipes in radiant floor or hot water baseboard systems.

In geothermal systems (i.e., ground-source heat pumps), pipes are buried in the ground either vertically or horizontally. A pump circulates a fluid through the pipes, which absorbs heat from the Earth. In many locations the ground below the frost line remains a constant 50° F, plus or minus a few degrees year round. (The warmer your average annual temperature, the warmer the temperature of the soil beneath your feet.)

Fig. 10-5: This geothermal system captures heat from the ground (geothermal heat) to heat a home. It can also be run in reverse to cool a home during the summer.

In air-source heat pumps, heat is drawn directly from the air outside a building — even on a cold winter day. The heat is then distributed through a building via ducts or pipes, as in other heating systems. Air-source heat pumps are able to extract heat from the environment on cold winter days because the refrigerant in the pump is colder than the air temperature. Heat moves from the slightly warmer outside air to the colder refrigerant. So, whenever the outside air is warmer than the refrigerant flowing through the pump, the latter will pick up heat.

The equipment in both geothermal and air-source heat pumps is powered by electricity. However, for every unit of electricity a geothermal system consumes during operation, it produces about four units of heat. (In contrast, an electric heater produces only one unit of heat for every unit of electricity it consumes.) Air-source heat pumps are slightly less efficient. For every unit of electricity they consume, they produce about three units of heat, give or take a little.

Because they operate on electricity, heat pumps require no combustion of fossil fuel. This eliminates the risk of combustion gases such as carbon monoxide seeping into a house and results in healthier indoor air. It also reduces the chances of a fire.

Heat pumps can also be used to cool buildings in the summer. When run in reverse, these systems extract heat from a building and deposit it either into the air, if you have an air-source heat pump, or the ground, in the case of a geothermal system. In addition, some of the heat from a heat pump can be used to heat water for in-home use. As a result, heat pumps serve three purposes: they heat buildings in the winter, they cool buildings in the summer, and they provide hot water year round.

Air-source and ground-source heat pumps can replace conventional furnaces and boilers in existing homes. They tie into existing heating distribution systems. If you are building a new home, consider installing a heat pump. Air-source heat pumps are typically installed in milder climates, although at least two manufacturers (Mitsubishi and Fujitsu) now produce units for use in pretty cold climates. Check with local installers to see if air-source heat pumps work in your area. Geothermal systems (ground-source heat pumps) are typically installed in colder climates.

So, should you install a heat pump to provide backup heat?

While heat pumps are more efficient and cleaner than conventional furnaces and boilers, geothermal systems cost more to install — about 25% to 100% more than a high-efficiency boiler or furnace (depending on location, local labor costs, and difficulty of the installation). Even so, they can save a substantial amount of money over the long-term. Air-source heat pumps are fairly economical to install and provide excellent savings, but may not be appropriate in extremely cold climates.

The higher cost of a geothermal system is due to the extensive excavation and/or drilling required to lay the heat-absorbing pipes in the ground. For new construction, this can be done before the finish grading is completed. Installation in an existing yard, especially a small one, is often more difficult and considerably more expensive. Pipes may need to be installed vertically to a depth of 200 feet. This requires a drill rig. Getting a drill rig into a backyard in an urban or suburban setting may be difficult or impossible. In such cases, a solar hot water system may be more economical, provided there’s sufficient Sun-bathed roof area for installation of the collectors.

Be sure that your new system is properly sized to your home, that is, it takes into account all the measures you’ve incorporated to increase your home’s energy efficiency, such as adding insulation and caulking air leaks in outside walls. As just mentioned, contractors tend to oversize heating systems, which results in lower operating efficiencies of heat pumps.

When shopping for a heat pump, look for an Energy Star-qualified model. Although a bit more expensive, the difference in initial cost will be offset by lower energy bills. To calculate your return on investment, visit www.aceee.org.

If you dramatically reduce heating requirements through air sealing and insulation and provide a significant amount of space heat via one of the solar technologies discussed in this book, a heat pump may not be worth the substantial investment. Why invest in a $20,000–$50,000 geothermal system to provide a couple hundred dollars worth of heat over the winter? You might be better off installing a smaller, energy-efficient furnace or boiler or an air-source heat pump.

If you still want a heat pump, research the various products and compare their performance. You can locate a heat pump installer in the Yellow Pages or by logging on to www.natex.org or www.acca.org. Ask for references and call them. Be sure to check with the Better Business Bureau to see if there have been any complaints against an installer before you sign a contract.

Fig. 10-6: Outdoor unit of an air-source heat pump that heats and cools my office and classroom at the Evergreen Institute.

Fig. 10-7:This photo shows the indoor unit of an air source heat pump. They are mounted on walls in rooms you want to heat or cool

Conclusion

We’ve now explored energy-efficiency measures, the major solar home heating technologies, and backup heating systems. As I’ve mentioned many times, the first step to heating your home with solar energy is efficiency: air sealing. The second is upgrading the insulation.

After sealing up and insulating your home, you have several options to pick from: passive solar, solar hot air, and solar hot water systems. You’ll need to assess each option carefully.

Passive solar is ideal for new homes — provided they are oriented to true south. This design can provide free heat for life at little, if any, additional cost. They also help maintain cooler temperatures in the summer.

Passive solar retrofits are possible, provided there’s plenty of south-facing wall that can be “opened up” by installing windows, or solarized by installing an attached sunspace. Don’t forget to include passive solar if you are building an addition onto an existing home or business.

Solar hot air systems work well, too, and require less structural modification of an existing home than a passive solar retrofit. Solar hot air collectors can be mounted on the south-facing walls of a building or on racks on the ground and oriented to ensure maximum solar gain.

Solar hot water systems (thermal systems) are ideal in applications in which the south-facing walls are shaded and therefore not amenable to passive solar or solar hot air systems. Of course, you need to have room on a sunny roof to install solar hot water collectors and room in your house to install the large solar storage tank. Solar collectors can also be installed on the ground next to a building and oriented for maximum solar gain.

All these technologies offer a very decent return on investment on their own, but they may also qualify for financial incentives, including tax credits and rebates. Financial incentives such as these lower the initial cost and make your investment in solar even more profitable.

Combined with energy-efficiency measures and an energy-efficient backup heating system, solar home heating systems can help save you money — a substantial amount of money — and dramatically reduce your environmental footprint, creating a greener world for the benefit of present and future generations and the millions of species that share planet Earth with us.