CHAPTER 43

Attacks on a Night School

According to the Communist way of thinking, not only should Socialist Party offices and unions be attacked, but anything that had anything to do with them, even a night school for young working-class people.

From the early twenties on in Warsaw, the Yugnt-Bund Tsukunft had been sponsoring night schools for young workers. Up until 1926, there were five such night schools, with several hundred students attending. To prevent the schools from being harassed by the police, Tsukunft created a special Educational Association called Veker (Awakener) as the legal body in charge of the schools. Pedagogically these night schools were associated with TSYSHO and even met in their schoolrooms. The two largest and most stable Tsukunft night schools were on Nowolipki 68 and Mila 51. These two night schools were very popular among the Warsaw Jewish young working people. These Jewish working class youths, who had never attended any kind of elementary school—they had to go to work as children—not only benefited from the general education being presented, but also from the broader cultural activities offered. And most importantly, they found a warm, comradely atmosphere. Two important cultural institutions developed from these night schools: The Tsukunft Chorus, under the direction of Yoysef Glatshteyn (killed by the Nazis), and the Dramatic Group, under the direction of M. Perenson (now in New York). The night schools were open to any Jewish young person and were also an important source of new recruits for Tsukunft. Hundreds of young people came to the Bund youth organization because of the night schools. The Communists couldn’t tolerate this. They began to harass our night schools.

They had started the harassments before, but in the beginning of the school year of 1929–1930 they put particular pressure on the night school on Miła 15, which lay in the very heart of Warsaw’s Jewish poverty. They would stand at the gate of the school and grab the students as they entered. They would break into the school facility itself, coming into the classrooms in the middle of a lesson and shouting, catcalling, etc. It went so far as throwing rocks at ten in the evening at the teachers and the students, who were going home. It became frightening for the young people to go home alone after class. Even the instructors had to be accompanied home by our militia. Mothers and fathers, older brothers and sisters, used to come in the evening to accompany the children home. Many students, although they were already working during the day, were still children of only 12–13 years of age. We had to call up our militia more and more often to drive the Communists away. The Communists began bringing their goons; there was hardly a night there wasn’t a fight at the night school.

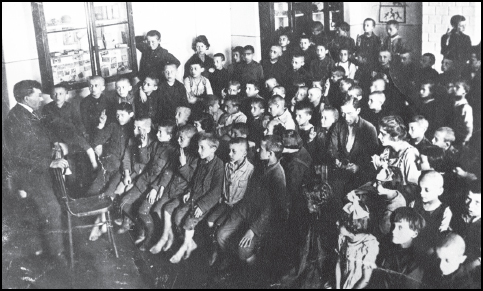

Figure 68. First school in Yiddish in Poland. Warsaw 1919. Leading class discussion, Shloyme Gilinski, founder and head of the school (later, Director of the Bund’s Medem Sanitarium. Notice children barefooted, too poor to own a pair of shoes and with heads shaved to rid them of lice. From the Archives of the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research, New York.

Once, at the beginning of winter 1930, when the youngsters were already sitting at their desks and quietly doing their lessons, rocks started flying into the classrooms through the windows—the school at 51 Miła was on the ground floor, so the windows faced the street. In a few moments the classrooms were full of rocks and broken glass. A few dozen windows were broken and several students hurt. There was panic in the school. The lessons were interrupted. The party Secretariat was called immediately and a group of Militiamen came, but met with no one. The Communists had already fled. From then on things were peaceful at the school. The Communists understood what kind of retribution awaited them for such a piece of work, and they no longer appeared at the school.

But the attack on the night school on Miła 51 was but child’s play compared to what the Communists did next.

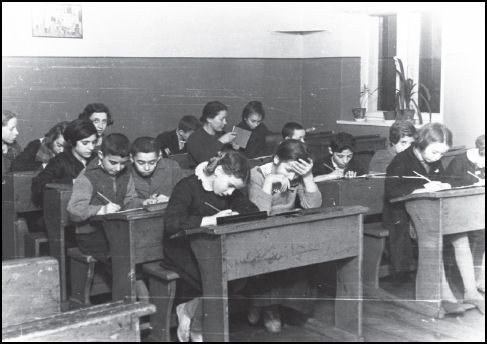

Figure 69. A class in a TSYSHO school, c. 1930. From the Archives of the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research, New York.

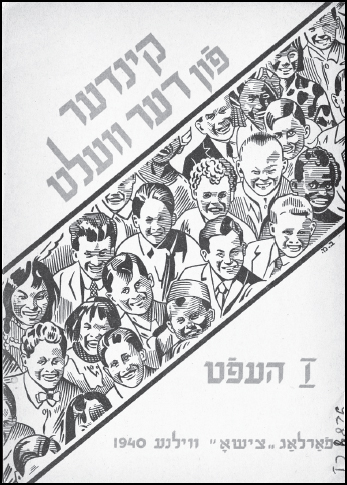

Figure 70. Students of the Michalewicz School in Bialystok, named after Beynish Michalewicz, Bundist leader and writer. From the Archives of the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research, New York.