CHAPTER 46

Krochmalna Street

Krochmalna Street was for a long time a Communist stronghold. In those days the street was called “Little Moscow” and “The Kremlin.” If a well-known Bundist walked through the street, they would yell after him “Bundist Krupnik” (Bundist Barley Soup). This was the Communist epithet for the Bund. It was supposed to mean that the Bund was concerned only about the material needs of the workers, and not for “higher” things, for the “revolution.” Communist terror ran rampant on the street. Bundist members handing out or posting flyers were beaten and driven from Krochmalna. Bundist posters were immediately torn down or not permitted to be posted at all.

Krochmalna was also long known as a stronghold of the underworld; this also prevented the spread of a Bundist influence in the area.

Krochmalna had a reputation in Warsaw as—for as long as I can remember—one of the poorest, most densely populated, and dirtiest streets in Warsaw. The walls of the houses (the houses were, in fact, large, with large courtyards) were deteriorating and dank. The street was narrow, and in many corners the sun never reached, the mud there never drying from one year to the next. The whole street, with its decaying, dark walls, with its mud, and gloomy people, was like a kind of black hole.

Krochmalna was encircled by large marketplaces: the “Gościnny Dwór” (later this marketplace was called “Welopole”); Gnojna Street, where Janusz’s market courtyard was located (a large marketplace at the end of Gnojna and Krochmalna), with many wholesalers of foodstuffs; and Mirowski Square, the center of fruit commerce. As a result, Krochmalna did not have many skilled workers, but mostly poor tradesmen at the surrounding marketplaces, and porters and teamsters, with stations there.

In addition, various people with uncertain means of livelihood lived on Krochmalna, along with criminal elements. What percentage of the residents were criminal types it is hard to say, but they ruled the street—especially the infamous “pletsl” (“little place” or square), a four-cornered square at Krochmalna 7 and 9. That was their “kingdom,” their chief exchange.

Another street of poverty was Smocza Street, but how great was the difference between Krochmalna and Smocza! Smocza was a lot cleaner, mostly inhabited by skilled workers who belonged to unions and to the Bund. Many of the children from Smocza were students in our secular Yiddish schools that were concentrated in that neighborhood. They belonged to SKIF, to Tsukunft, or to other progressive youth organizations. The Smocza neighborhood was a center of Jewish organized labor. Despite its poverty, the street was lively and happy.

Two centers of Warsaw Jewish poverty—but how different!

The Bund did not give up on Krochmalna Street. After the parliamentary elections of 1922, we made a concerted effort to lift the street out of its social and moral abyss. The Bund created a special commission for the Krochmalna region whose job it was to broaden the Bund’s influence there. A secular Yiddish school was opened at Krochmalna 36. It was an immediate success. The children who attended the new secular Yiddish TSYSHO school began bringing home new cultural outlooks and manners that slowly began influencing their homes, not least of which, it should be mentioned, was washing your hands before eating, something they brought home from school. Through the children, the school became a cultural factor in the homes of Krochmalna. The schools also had an influence on the homes directly, through parental meetings and teacher visits to the students’ homes. A large number of the children were recruited by SKIF, and these new SKIFists brought home new songs, quite different from the ones that used to be sung on Krochmalna. They dragged their parents to cultural evenings the Bund or the Kultur-Lige organized. In short, dos redele hot zikh ibergedreyt (literally, “the little wheel had turned over,” i.e., “things changed”) and the children were teaching their parents and becoming the bearers of culture in their homes.

The party also worked through the unions. A number of the members of the Meat Workers Union and of the Transport Workers Union, as well as of other of our unions, lived in the neighborhood of Krochmalna. Through them we started spreading Bundist literature and recruiting readers for the Folkstsaytung. At special party meetings of Bundists from the neighborhood, the difficulties surrounding our work on Krochmalna Street were continually discussed. Also our youth group, Tsukunft, organized several circles of Krochmalna young people and created a special Krochmalna section.

When the work of the Bund, Tsukunft, and SKIF had taken root, the Bund rented an office at 14 Grzybowska Street, very close to Krochmalna, and established a club there for the SKIFists, Tsukinftists, and adult Bundists of the neighborhood. The Warsaw Committee of the Bund appointed a special delegate for the activities of this new region, Comrade Abrasza Blum, one of the leaders of the wartime underground Bund and later hero of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising.1 Tsukunft delegated a person who was one of the rarest and finest individuals—Yankele Mendelson. Khayim Ejno led the SKIF work. A group of our women comrades decorated the club, making it more attractive and remaining on duty in the evenings. Especially active in this work were the comrades and students Dina Berman (the daughter of Leybetshke Berman, now Dina Mlotek, living in New York), and the Tsukunftist Yentl Bergman (active in the Warsaw Ghetto; she perished there), and many others.

In time Krochmalna became a Bundist stronghold. We overcame the dominance and terror of the Communists. The power of the underworld was broken, and in the end the Bund was the main force in the whole neighborhood. In the municipal elections of 1938 the Bund won two out of the three seats from this neighborhood. Also the whole surrounding region, like the other electoral regions in Jewish Warsaw, became, in its majority, Bundist.

The Krochmalna neighborhood was exceptional with its unique types. It is worthwhile telling about some of them.

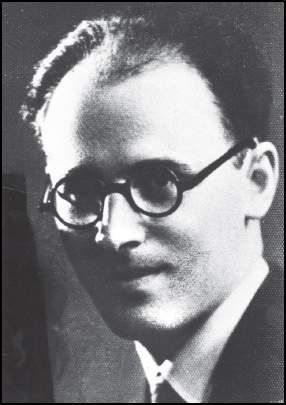

Figure 82. Abrashe Blum, Bund hero of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising, shot dead by Gestapo, summer of 1943. From the Archives of the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research, New York.

Figure 83. Warsaw Tsukunftists on a hike to a Bund camp in Gabin, Poland, 1938. From the Archives of the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research, New York.

Note

1.Blum, Abrasza (1905–1943): By profession, a structural engineer. Beginning in 1930, a director of the Folkstsaytung. In September 1939, participated in the defense of Warsaw, helping to organize all-Jewish detachments. When Warsaw fell, most of the Bund’s senior leadership evacuated the city: they were too well-known; the leadership of the party fell to the Youth-Bund Tsukunftists. Abrasza worked in the ghetto brush factory, 1942–1943. He was Bund representative to the Jewish Fighting Organization (ZOB). Escaped the burning ghetto through the sewers, hiding in the apartment of the Bund courier, Władka. The janitor reported him to the Gestapo. Abrasza escaped through the window on a rope made from bedsheets, but broke his legs in the fall from the third story; captured and murdered by the Gestapo in 1943.—MZ