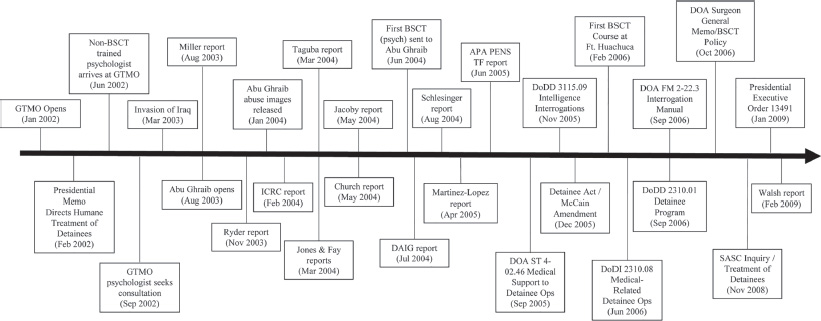

Figure 11.1. Chronology of BSCT-related events, investigations, and regulations

Whatever you do, you need courage. Whatever course you decide upon, there is always someone to tell you that you are wrong.

—Ralph Waldo Emerson

Interrogation is an inherently psychological endeavor, and there is nothing unethical in psychological support to interrogation, not by law enforcement, the intelligence community, or the military. The setting in which such activities take place is also not a matter of ethics unless such conditions are demonstrably in violation of U.S. law or supporting the mistreatment of individuals under U.S. custody. Despite this admonition, the greatest ethics-related lightning rod associated with operational psychology is its support to interrogation (specifically, its connection to a handful of psychologists who were involved with events immediately following 9/11). In this chapter I will provide a description of how psychological support to military interrogations can be, and has been, conducted ethically and effectively.

Law enforcement personnel often interrogate criminal suspects in the standard course of their investigations. These interrogations (also referred to as investigative interviews or inquiries) may involve coercive tactics, including intimidation, lying to suspects, and other pressures (Kalbeitzer, 2009). Despite this coercion, these tactics have been deemed legal by U.S. courts (Melton, Petrila, Poythress, & Slobogin, 2007). The reason for this may, in part, be due to the provision of a suspect’s rights to access legal counsel and to remain silent under questioning (Miranda v. Arizona, 1966). These rights, authorized by a ruling of the U.S. Supreme Court (1966), can also be waived by suspects voluntarily.

Psychologists working for law enforcement agencies routinely provide consultation to interrogation and investigative interviewing. In fact, psychologists have applied their knowledge of behavioral science to this challenging environment for decades (IACP, 2016; Reese, 1995; Reese & Horn, 1988). Their efforts have often centered on aiding investigations, enhancing investigative inquiry, and injecting behavioral science into the investigative process (Corey, 2012; Ewing & Gelles, 2003; Fein, 2006, 2009). This work has resulted in rapport-based approaches largely supplanting coercive methods as the norm. Operational psychologists have been successful in dispelling myths and misperceptions about what works, and what doesn’t, when it comes to different forms of investigative inquiry (Fein, 2006, 2009; Kassin, 2014; Loftus, 2011; Porter, Rose, & Dilley, 2016; Vrij, Mann, & Leal, 2013). Psychologists practicing in this arena have also made significant contributions to the assessment of deception and the reliability and credibility of suspect statements (Morgan, Rabinowitz, Hilts, Weller, & Coric, 2013; Sabourin, 2007), threat detection (Gelles, Sasaki-Swindle, & Palarea, 2006), and hostage negotiations (Porter et al., 2016; Rowe, Gelles, & Palarea, 2006).

The military rests its authority to detain and interrogate non-U.S. persons (identified as potential terrorist threats) on the Authorization for Use of Military Force (AUMF; U.S. Congress, 2001). The AUMF is informed by the Law of War, and it is affirmed by the National Defense Authorization Act (U.S. Congress, 2012). The Supreme Court (see Hamdi v. Rumsfeld, 2004) confirmed this authorization as did the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia. This is an important acknowledgment since some critics of operational psychology have alleged that persons under U.S. military detention have been held in violation of the law. The U.S. Supreme Court has determined this to be untrue. Moreover, the Court has determined that facilities and conditions present at Guantanamo Bay Naval Base (GTMO) are in keeping with our obligations to the United Nations Charter. In 2009, President Obama issued Executive Order 13491, affirming as much and reissuing our nation’s commitment to prohibiting torture and other cruel, inhuman, and degrading treatment (DoJ, 2012). Furthermore, he directed the use of only those interrogation techniques set forth in the Army Field Manual (DoA, 2006a) and other authorized federal law enforcement techniques. This was a reaffirmation of what had previously been in place under the McCain Amendment (Detainee Act of 2005; U.S. Congress, 2005). At the same time, the Military Commissions Act of 2009 passed with wide bipartisan support (U.S. Congress, 2014). This legislation further levied legal requirements on military commissions to ensure all legal proceedings supported a presumption of innocence; reasonable-doubt burdens of proof; the right to counsel of their choosing; representation if unable to afford such counsel; and the rights to compel witnesses, present evidence, and appeal (DoJ, 2012). While not identical to protections afforded under Miranda, these provisions are similar in many substantive ways.

It is not my intention to re-hash the past nor to re-assert arguments that have already been made (see Dunivin, Banks, Staal, & Stephenson, 2011; Greene & Banks, 2009). However, some historical context is instructive, and setting the record straight can be valuable in so far as it helps inform our way forward. To this end, a brief review of the facts and chronology of events has been provided.

In the early days following 9/11, two contracted Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) psychologists helped design a program of harsh interrogation, including waterboarding, that was not in keeping with the nation’s moral compass nor the profession’s ethical standards of conduct (Mitchell & Harlow, 2016; SASC, 2008). In addition, two military psychologists (both clinicians) were pressed into service as would-be interrogation consultants at Guantanamo Bay. These two clinicians had no prior training and limited supervision and consultation as behavioral science consultants (BSCTs). Neither had ever worked in an operational capacity. At the time, there was no Department of Defense (DoD) instruction guiding their roles or responsibilities, and there was no formal training program to prepare them (SASC, 2008; Staal, 2017, 2018). Their actions have been widely criticized and mischaracterized in the common press and literature (James, 2008; Risen, 2014). As evidence of their protestation and thoughtfulness, this first “BSCT” team drafted a preliminary BSCT policy. While their inclusion of many SERE-like training elements and coercive methods has been heavily criticized, they also added the following overarching caveat:

Experts in the field of interrogation indicate the most effective interrogation strategy is a rapport-building approach. Interrogation techniques that rely on physical or adverse consequences are likely to garner inaccurate information and create an increased level of resistance… . There is no evidence that the level of fear or discomfort evoked by a given technique has any consistent correlation to the volume or quality of information obtained… . The interrogation tools outlined could affect the short term and/or long term physical and/or mental health of the detainee. Physical and/or emotional harm from the above techniques may emerge months or even years after their use. It is impossible to determine if a particular strategy will cause irreversible harm if employed. (SASC, 2008, p. 52)

When this memo was received by the army’s senior operational psychologist, he wrote back to the GTMO BSCT team, “My strong recommendation is that you do not use physical pressures…[If GTMO does decide to use them] you are taking a substantial risk, with very limited potential benefit” (SASC, 2008, p. 53). The BSCT team was then provided with arguments and supportive research illustrating how such pressures are designed to build resistance, not remove it.

These passages and references have been provided to readers in the hope that they provide both historical context and a better understanding of the intent and position adopted by operational psychologists concerning BSCT activities and conduct. Critics prefer to see these events in black and white, with the benefit of hindsight, and through a contemporary lens. The paths set before thoughtful and ethical professionals are often less well defined when experienced in the moment. It is by this second criterion that we as a profession judge the reasonableness of action, not the former (APA, 2017).

Despite these regrettable, yet verifiable facts, many have portrayed these events differently. Fear mongering, innuendo, suspicion, and a well-resourced mis-information campaign have promoted the notion that military psychologists were torturing detainees, or at least complicit in such acts. Furthermore, it has been suggested that such behavior was systemic and widespread (Bloche & Marks, 2005; Kalbeitzer, 2009; Lifton, 2004; Marks, 2005; Mayer, 2005). A formal ethics complaint was leveled against this BSCT, and the facts of his case were reviewed by the APA’s ethics office, who concluded that no sanctioning or administrative action was appropriate (Eidelson, 2015). It has been argued that military psychologists, due to their intractable dual agency dilemmas, and their requirement to blindly follow orders, are unable to act with moral autonomy and resist pressures from the military and the CIA, resulting in unethical and immoral decision making (Arrigo, Eidelson, & Bennett, 2012; LoCicero, 2017). This is a gross misrepresentation of the truth, yet it persists to this day.

Prior to the events of 9/11, military psychologists, as uniformed service members, were obligated to comply with various government regulations related to the treatment of detainees under U.S. custody. The Geneva Conventions (Common Article III) is one such example (ICRC, 1949), while army regulation 190–8 (DOA, 1997) is another such document. Both direct the humane treatment of all detained persons within U.S. custody. The Law of Land Warfare (DoDD, 5100.77, 1998), the Law of Armed Conflict (FM 27–10, DOA, 1956), and even the military’s Army Field Manual (FM 34–52) for interrogation also make clear this provision (DOA, 1992). Psychologists also were able to find guidance from the APA’s Ethics Code and other statutes and standards as licensed professionals. Furthermore, immediately following 9/11, President Bush, as advised by the Department of Justice, issued a White House memorandum (POTUS, 2002) directing that al Qaida and Taliban detainees be treated humanely and in a manner in keeping with the Geneva Conventions.

Following the tragedy of Abu Ghraib and the surfacing of other abuse allegations, a series of independent investigations were launched, each named for its investigating officer. Although a thorough exposition of these various investigations is not possible here, I will provide a summary of any that references BSCT activities.

The Church Report, commissioned by the secretary of defense, was directed to explore allegations of detainee abuse (DoD, 2004a). The report provides a brief overview of BSCT duties, comparing them to forensic consultation. Church specifies that BSCT personnel are not involved with detainee medical care and do not have access to detainee records. Church’s investigation reports an episode during which an operational psychologist, working as a BSCT, suspected detainee abuse. According to the report, the BSCT reported his concerns, recommended the interrogation be stopped, and sought medical care for the detainee (DoD, 2004a, p. 367).

The Schlesinger Report, also directed by the secretary of defense, established an independent investigative body to review detainee abuse allegations and findings from previous reports (DoD, 2004b). While this report does not detail BSCT activities or conduct per se, it does include an extensive discussion regarding the psychological research related to detainee abuse risks. Included in the report are lessons learned from Zimbardo’s Stanford Prison study, Bandura’s moral disengagement research, and other relevant behavioral science literature (Bandura, 1986; Zimbardo, 1971).

In May 2004, the Office of the Inspector General for the DoD directed an investigation of alleged detainee abuse, to include a review of previous investigations. Although this report provides limited details regarding the work of BSCTs, it does recommend the development of a BSCT policy and training program (indicating that there was none at that time). Furthermore, it recommends that more senior psychologists serve in this capacity (DoD, 2004c).

The Martinez-Lopez Report provides the greatest detail regarding BSCT activities. This report was directed by the surgeon general of the army, intended to review military medicine’s role with detainee operations. The report indicates that BSCTs provided consultation to assist the military in conducting safe, legal, ethical, and effective interrogation and detainee operations. Moreover, it concludes, “There is no indication that BSCT personnel participated in abusive interrogation practices” (DOA, 2005, Section VII, 18–17, p. 102). The report further recommends that “the DoD should develop well-defined doctrine and policy for the use of BSCT personnel. A training program for BSCT personnel should be implemented to address the specific duties” (DOA, 2005, p. 8). The report characterizes BSCT activities as similar to forensic consultation: offering opinions on character and personality, assessing dangerousness in detainees, and providing consultation on camp organization and procedures. The report clarifies that BSCT personnel “observed interrogations but were not active participants in the interrogation process” (DOA, 2005, p. 103). This report also highlights one instance in which a military BSCT member reported an allegation of abuse to his chain of command. The following excerpt captures the general assessment of BSCT activities between 2003 and 2005.

There is clear evidence that BSCT personnel took appropriate action and reported any questionable activities when observed. BSCT personnel served as protectors, much like safety officers to ensure the health and welfare of the detainee under interrogation. In reviewing interrogation plans with the ability to halt interrogations at any time, BSCT personnel provide the oversight and checks and balances in the interrogation process. (DOA, 2005, Section VII, 18–21, p. 106)

In summation, these various independent reports found many shortcomings with the DoD’s interrogation and detention operations; however, BSCT activities or conduct was not one of them. In no instance were BSCTs cited as being involved in abusive activities; on the contrary, the tendency was to highlight their presence and involvement in positive and supportive terms. This was in stark contrast to the review and critique of other interrogation and detention services. In other words, it stands to reason that if there had been inappropriate conduct by BSCT personnel, this would have been reported. Other such misconduct or shortcomings were identified in these reports accordingly. There is no reason that BSCTs would represent an exception.

In the wake of the detainee abuse revelations (and the many investigations that followed), a number of positive developments emerged: (1) a formal training program for BSCTs was created in 2006 (Staal, 2017), (2) an army medical policy was established (DOA, 2006b), (3) strict local policies were adopted, (4) a DoD instruction detailing BSCT roles and responsibilities was published (DoD, 2006), and (5) unequivocal guidance from the U.S. government was secured (U.S. Congress, 2005). These events were also the catalyst for an APA task force addressing ethical issues in operational psychology practiced within national security settings (APA PENS TF, 2005).

Figure 11.1 provides a highlight of these events in chronological sequence.

Due to the upheaval and confusion created by the APA’s Hoffman Report (APA, 2015), members of the APA voted to prohibit military psychologists from providing medical and mental healthcare to detainees in addition to prohibiting their support to any national security interrogations. Justification for these decisions was based on the false assertion that U.S. detention facilities were not compliant with U.S. law or international treaty. Ironically, the opposite has been demonstrated and determined by the Supreme Court, the president of the United States, and the Department of Defense. Nonetheless, the APA’s actions to prohibit psychologists from supporting detainees are in direct violation of Common Article III of the Geneva Conventions. According to U.N. treaty and U.S. law, detaining powers are compelled to provide medical and mental healthcare to persons under their custody. Thus, the APA’s actions have made detainees less protected now than they were prior to the prohibition, and they have advocated a breech in established international law and treaty as opposed to supporting it. An attempt was recently made to reinstate support for this obligation, proposed by the Society for Military Psychology (APA’s Division 19); however, the APA’s Council of Representatives has remained unsupportive (APA, 2018). The APA’s reaction to the Hoffman Report has been characterized as “knee-jerk” and “misinformed” by others outside the controversy (Porter et al., 2016).

As stated previously, psychological consultation to law enforcement, intelligence, and military interrogations is not new. However, this support to military interrogation and detention activities was uncommon and infrequent prior to 9/11. Psychologists’ work in this area quickly demonstrated utility in the eyes of intelligence and law enforcement professionals. There was a desire to increase the quality of inquiry by interrogators and investigators, and psychologists, as experts in human behavior, learning, and communication, were naturally seen as ideal for the task. This recognition was paired with a sense of great urgency to prevent abuse in the wake of the revelations coming out of Abu Ghraib prison in Iraq. Although Milgram’s compliance research, Zimbardo’s famous Stanford prison study, and Bandura’s work on moral disengagement and behavioral drift should have provided us with sufficient warning, the tragic images that began to surface from overseas facilities proved otherwise (Bandura, 1986; Milgram, 1963; Zimbardo, 1971).

These two factors, the perceived value in pairing psychologists with investigative teams along with psychologists’ unique appreciation for risk mitigation and behavioral drift, fueled the desire to employ BSCTs throughout the military’s interrogation and detention architecture. Following the initial employment of untrained clinicians into the BSCT role, there was a recognition that formal training and guidance for psychologists employed as BSCTs were needed. In response, the DoD published several key documents: (1) an overarching directive governing how interrogations are to be conducted (including reference to BSCT support), DoD Intelligence Interrogations, Detainee Debriefings, and Tactical Questioning (DoD 3115.09, 2005), (2) a regulation detailing medical activities as they relate to military interrogation and detention operations (Department of Defense Instruction (DODI) 2310.08 Medical Program Support for Detainee Operations (DoD, 2006), and (3) a Department of the Army Medical Command Memorandum specifying the BSCT mission, roles, and responsibilities, U.S. Army’s Medical Command Policy Memo 06–029 (DOA, 2006b). These documents were immediately adopted as mandatory guidance for all DoD medical personnel (including psychologists working as BSCTs). For the first time, military members had proper guidance regarding the application of behavioral science to interrogation and detention operations. There hasn’t been a single documented allegation of misconduct lodged against a military BSCT operating under these governing documents.

Synchronized with the drafting of the DoD’s guidance, senior psychologists with experience in ethics, military psychology, and the BSCT mission began designing the first formal BSCT training course. In February 2006, the first BSCT training class was held at Ft. Huachuca, Arizona (the home of Army Intelligence). Over the intervening months, the training program was expanded and refined, becoming a three-week in-residence course, recognized by the DoD and made mandatory for any and all psychologists assigned to a BSCT mission prior to their deployment. Over the course of the last decade, scores of psychologists have successfully completed this training and have provided safe, legal, ethical, and effective support to military interrogation and detention operations.

The Army Field Manual (FM 2–23.3) operationally defines interrogation as,

the process of questioning a source to obtain the maximum amount of usable information. The goal of any interrogation is to obtain reliable information in a lawful manner, in a minimum amount of time, and to satisfy intelligence requirements. (DoA, 2006a, p. 8)

According to DoD doctrine, BSCs (the psychologist-member of the BSCT) are chartered to “make psychological assessments of the character, personality, social interactions, and other behavioral characteristics of interrogation subjects, and to advise authorized personnel performing lawful interrogations regarding such assessments” (DoDD 3115.09, 2005, Section 3.4.3.3). The overarching mission of a BSCT is to provide psychological expertise and consultation in order to assist the military in conducting safe, legal, ethical, and effective detention operations, intelligence interrogations, and detainee debriefing operations (DoA OTSG/MEDCOM Policy Memo 06–029, 2006). This mission is composed of two complementary objectives:

Psychologists do not conduct or direct interrogations. This has been a common misperception among detractors. DoDI 2310.08 makes it very clear, “BSCs may observe, but shall not conduct or direct, interrogations” (DoD, 2006, Section E2.1.2). BSC psychologists provide training to interrogators and investigators on active listening, communication, and cultural sensitivity. In addition, BSCs are focused on environmental considerations that may impede the process, and “BSCs may advise command authorities on detention facility environment, organization and functions, ways to improve detainee operations, and compliance with applicable standards concerning detainee operations” (DoD, 2006, Section E2.1.4). The role of psychologists who consult to national security or defense interrogations is similar to that of a psychologist working in law enforcement. Police psychologists observe interrogations and investigative interviews, provide feedback and consultation to law enforcement personnel, may be involved in the training of investigators, conduct direct and indirect assessments of informants and suspects, and perform psychological autopsies of victims (Corey, 2012; IACP, 2016; Kitaeff, 2011; Reese & Horn, 1988).

Following allegations of abuse and requests from Human Rights First, Human Rights Watch, the American Civil Liberties Union, and Amnesty International, President Obama, by executive order, directed an investigation and review of interrogation and detention operations at GTMO in 2009 (known as The Walsh Report). The following descriptions of BSCT activities appeared in the investigative report:

Behavioral Science Consultant Team (BSCT) personnel may observe interrogations, but may not conduct them or be present in the interrogation room. The BSCT advises interrogators in a manner similar to psychologists assisting in criminal investigations, but does not plan, conduct or direct interrogations. The BSCT also serves as yet another oversight mechanism; responsible for observing interrogators for “drift” in their personalities or interrogation practices that may tend toward unauthorized interrogation behavior. (DoD, 2009, p. 62)

As already mentioned, employment of psychologists in this manner was not without controversy, and several concerns were raised immediately by critics: (1) Psychologists have a duty to do no harm, isn’t this a contradiction to their role? (2) Psychologists shouldn’t use medical or mental health information to exploit others. (3) BSC psychologists are in an impossible dual agency role (navigating both medical and operational masters). (4) The power of the situation is too great for psychologists; they will be unable to speak out against abuses. I have provided a brief response to address each of these concerns next.

Critics have suggested that psychologists should never do harm. However, this position is overly simplistic. Grisso (2001) has aptly noted that psychologists often must do harm but do so ethically. They breach confidentiality, triage medical necessity, conduct research that may manipulate or deceive, report individuals to state agencies that may result in lengthy prison terms, and render testimony that separates parents and children. The APA Ethics Code does not place a premium on our obligations to individuals over and above our obligations to society and Standard 3.04 of the APA Ethics Code acknowledges that at times psychologists will cause harm. Our ethical obligation is to mitigate harm where it is reasonably possible to do so.

In anticipation of this concern, the DoA was clear and unequivocal in its guidance, “BSCs are psychologists … not assigned to clinical practice functions, but to provide consultative services to support authorized law enforcement or intelligence activities, including detention and related intelligence, interrogation, and detainee debriefing operations” (DoA, 2006). As such, BSCs are assigned to a different chain of command in order to separate them from their medical and mental health counterparts who work on behalf of the detainee’s medical treatment team. Access to medical records, mental health histories, and related information is restricted to prevent individuals (to include BSCs) from using such information inappropriately.

Opponents of operational psychology argue that resolution of dualities is both necessary and often impossible, and the BSC role is provided as one such example. It should be noted that according to the APA Ethics Code, dual relationships are not inherently unethical and may or may not require resolution. Much has been written about addressing these dualities in military psychology (Jeffrey, 1989; Jeffrey, Rankin, & Jeffrey, 1992; Johnson, 1995, 2008; Johnson, Ralph, & Johnson, 2005; Kennedy & Johnson, 2009; Staal & King, 2000). Anecdotal evidence suggests that potential conflicts are rarely unresolvable when ethics are concerned, and the military has generally proven itself to be adaptive in responding to ethical concerns by psychologists when raised. There is nothing unique to the dual agency challenges as a BSC that do not exist elsewhere for any military psychologist or organizational consultant. Navigating third-party consultation, where the organization is the identified client as opposed to the subject of the psychologist’s services, always represents challenges but rarely results in conflicts that aren’t sufficiently resolved.

Some have suggested that when psychologists work as BSCs, they face military organizational pressures that cause them to abandon their ethical obligations. This is simply false. It should be noted that these risks are no greater for operational psychologists or BSCs than they are for clinicians working within the military or embedded organizational civilian counterparts. Mark Fallon (2017), in his book, Unjustifiable Means: The Inside Story of How the CIA, Pentagon, and US Government Conspired to Torture, and Paul Lauritzen (2013), in his book, The Ethics of Interrogation: Professional Responsibility in an Age of Terror, chronicle the actions of Dr. Michael Gelles, former chief operational psychologist at Naval Criminal Investigative Service (NCIS) during his visit to GTMO in 2002. Dr. Gelles reported his concerns about potential abuse to the NCIS director and Office of Legal Counsel. His assessment of the situation and decision to report was a result of his experience as an operational psychologist and his having worked in support of interrogations. Dr. Gelles, a former naval officer, was working for the DoD in a third-party consultative role. All the dynamics were present that critics suggest would prohibit his ability to speak out as an autonomous moral agent, yet he did so without hesitation.

Psychologists attending military BSCT training complete a three-week in-residence course at Ft. Huachuca, Arizona. In addition, there is a distance-learning requirement that is completed prior to arrival to the course. Class sizes are small to facilitate a positive instructor-to-student ratio and to facilitate individual mentoring relationships between would-be BSCTs and the course cadre. Psychologists are provided with an initial overview of the coursework, the BSCT mission, roles, and responsibilities and an introduction to the facilities and theaters in which they will conduct their work. Ethical and moral concerns are addressed early and often throughout the course. A legal expert and an ethicist are brought in as part of the training to facilitate discussions of applicable psychological and medical ethics, U.S. and international law, a review of the Geneva Conventions, the McCain Amendment, relevant Supreme Court rulings, and DoD regulations and instructions. Two days are spent reviewing and discussing these critical, foundational issues in addition to what the APA Ethics Code and related policies promote.

Members of different faith and culture traditions are included to sensitize psychologists to their unique perspectives. Experts in cultural history, ethnic, tribal, and sectarian divisions, and current socio-political issues relevant to the regions considered, are also part of the curriculum. Contemporary perspectives on terrorism and insurgency are reviewed and discussed. Cadre are selected for the recency of their experience as well as depth of knowledge. Feedback from recently serving BSCTs and facility staff is also incorporated into the training. A panel of interrogators and intelligence professionals who have recently returned from theaters of conflict are included as well. In addition, BSCT students learn about various intelligence collection methods, the use of interpreters, and information security.

Relevant research is reviewed concerning investigative inquiry, methods toward building rapport, cross-cultural awareness, the effects of stress on memory and recall, and common reactions to captivity (Alison, Alison, Noone, Elntib, & Christiansen, 2013; Goodman-Delahunty & Howes, 2016; Meissner, Oleszkiewicz, Surmon-Böhr, & Alison, 2017). Studies in compliance, moral disengagement, behavioral drift, and risk management are also reviewed (Bandura, 1986; Milgram, 1963; Zimbardo, 1971). Various perspectives from law enforcement, criminal investigation, and intelligence communities are considered. Myths and misperceptions about deception detection as well as what the research literature says about educing information are addressed (Fein, 2006, 2009; Morgan et al., 2013; Sabourin, 2007). Research in the areas of organizational behavior, social psychology, and principles of persuasion and influence is discussed and illustrated with real-world applied examples. Research findings concerning the risk of false confession and bias in decision making are highlighted.

Finally, several days are devoted to role-playing with interrogators, detention facility staff, and interpreters. Students are exposed to well-accepted models of consultation and are given ample time to exercise these models under the supervision of trained BSCs and other cadre. The course provides a safe environment for students to explore their concerns, try out novel skills, and gradually develop a sufficient degree of mastery in observation and consultation to interrogation. Toward the end of the course, BSCTs are encouraged to discuss any reservations or ethical concerns about their participation in the mission. As a culminating exercise, students draft an after action report (AAR), providing the cadre and course director with information to improve the course and to address specific concerns that may not have been brought up during normal classroom discussions.

A great deal of effort and resources have been extended to ensure the professionalism of the BSCT cadre, to enhance the quality and depth of the course curriculum, and to address ethical concerns and sensitivities surrounding the role of psychologists as BSCTs (Staal, 2017).

Psychology has a role to play in all areas of human endeavor. Interrogation and detention operations are no exception. The promotion of safety, compliance with the law, ethical standards that raise professional conduct, and ensuring the effectiveness of our efforts are all worthwhile objectives for psychology to support. BSCT psychologists share these goals in their support to law enforcement, intelligence, and military investigations. It is unfortunate, and deeply troubling that needless and near-sighted prohibitions have been levied against the psychologist’s ability to support lawful interrogations. The absence of psychology to human challenges is not the answer. On the contrary, such a move is counter to the mission of psychology as stated in the APA’s Ethics Code, “to improve the condition of individuals, organizations, and society” (APA, 2017, p. 3)

Alison, L. J., Alison, E., Noone, G., Elntib, S., & Christiansen, P. (2013). Why tough tactics fail and rapport gets results: Observing Rapport-Based Interpersonal Techniques (ORBIT) to generate useful information from terrorists. Psychology, Public Policy and Law, 19, 411–431. doi.org/10.1037/a0034564

American Psychological Association. (2005). Report of the American Psychological Association presidential task force on psychological ethics and national security. Washington, DC: Author.

American Psychological Association. (2015). Independent review relating to APA ethics guidelines, national security interrogations, and torture. Sidley Austin, LLP (David Hoffman). Washington, DC: Author.

American Psychological Association. (2017). Ethical principles of psychologists and code of conduct. American Psychologist, 71, 900.

American Psychological Association. (2018). APA rejects proposal expanding role of military psychologists to treat detainees in all settings. Retrieved from https://www.apa.org/news/press/releases/2018/08/military-psychologists-detainees

Arrigo, J. M., Eidelson, R. J., & Bennett, R. (2012). Psychology under fire: Adversarial operational psychology and psychological ethics. Peace and Conflict: Journal of Peace Psychology, 18(4), 384–400.

Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundation of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Bloche, M. G., & Marks, J. H. (2005). Doctors and interrogators at Guantanamo Bay. New England Journal of Medicine, 353, 6–8.

Corey, D. M. (2012). Core legal knowledge in police & public safety psychology. Paper presented at the American Board of Professional Psychology Summer Workshop Series, Boston, MA, July 11, 2012.

Department of Defense. (1998). DoD Law of War Program (DoDD 5100.77). Washington, DC: Author.

Department of Defense. (2004a). The Church report. Office of the Secretary of the Department of Defense. Washington, DC: Author.

Department of Defense. (2004b). The independent panel to review DoD detention operations (The Schlesinger report). Office of the Secretary of the Department of Defense. Washington, DC: Author.

Department of Defense. (2004c). Review of DoD-directed investigations of detainee abuse. Office of the Inspector General of the Department of Defense. Washington, D: Author.

Department of Defense. (2005). DoD intelligence interrogations, detainee debriefings, and tactical questioning (DoDD 3115.09). Washington, DC: Author.

Department of Defense. (2006). Department of Defense Instruction 2310.08: Medical program support for detainee operations. Washington, DC: Author.

Department of Defense. (2009). Review of department compliance with president’s executive order on detainee conditions of confinement (The Walsh report). Washington, DC: Author.

Department of Justice. (2012). Report on U.S. detention policy. Consolidated and Further Continuing Appropriations Act, 2012, Pub. L. No. 11 2–55. Washington, DC: Author.

Department of the Army. (1956). The law of land warfare, FM 27–10. Washington, DC: Author.

Department of the Army. (1992). Army field manual (FM 34–52) intelligence interrogation. Washington, DC: Author.

Department of the Army. (1997). U.S. Army regulation 190-8 enemy prisoners of war, retained personnel, civilian internees and other detainees. Washington, DC: Author.

Department of the Army. (2005). Final report: Assessment of detainee medical operations for OEF, GTMO, and OIF. Martinez-Lopez report, Office of the Surgeon General. Washington, DC: Author.

Department of the Army. (2006a). Field manual (FM) 2–23.3, intelligence interrogation. Washington, DC: Author.

Department of the Army. (2006b). OTSG/MEDCOM policy memo 06–029: Behavioral science consultation policy. Washington, DC: Author.

Dunivin, D., Banks, L. M., Staal, M. A., & Stephenson, J. (2011). Interrogation and debriefing operations: Ethical considerations. In C. Kennedy and T. Williams (Eds.), Ethical practice in operational psychology. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Eidelson, R. J. (2015). “No cause for action”: Revisiting the ethics case of Dr. John Leso. Journal of Social and Political Psychology, 3(1), 198–212.

Ewing, C. P., & Gelles, M. G. (2003). Ethical concerns in forensic consultation concerning national safety and security. Journal of Threat Assessment, 2, 95–107.

Fallon, M. (2017). Unjustifiable means: The inside story of how the CIA, Pentagon, and US government conspired to torture. New York: Regan Arts.

Fein, R. (2006). Educing information: Science and art in interrogation—Foundations for the future (Intelligence Science Board Study on Educing Information Phase 1 report). Washington, DC: National Military Intelligence College Press.

Fein, R. (2009). Intelligence interviewing: Teaching papers and case studies (Intelligence Science Board Study). Washington, DC: National Military Intelligence College Press.

Gelles, M. G., Sasaki-Swindle, K., & Palarea, R. E. (2006). Threat assessment: A partnership between law enforcement and mental health. Journal of Threat Assessment, 2, 55–66.

Goodman-Delahunty, J., & Howes, L. (2016). Social persuasion to develop rapport in high-stakes interviews: Qualitative analyses of Asian-Pacific practices. Policing and Society: An International Journal of Research and Policy, 26, 270–290.

Greene, C., & Banks, M. (2009). Ethical guideline evolution in psychological support to interrogation operations. Consulting Psychology Journal: Practice and Research, 61(1), 25–32.

Grisso, T. (2001). Reply to Shafer: Doing harm ethically. Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry Law, 29, 457–60.

International Association of Chiefs of Police. (2016). Consulting police psychologist guidelines. San Diego, CA: International Association of Chiefs of Police.

International Committee of the Red Cross. (1949). Geneva Convention relative to the protection of civilian persons in time of war (Fourth Geneva Convention), August 12, 1949, 75 UNTS 287. Retrieved from https://www.refworld.org/docid/3ae6b36d2.html

James, L. E. (2008). Fixing hell: An army psychologist confronts Abu Ghraib. New York: Grand Central Publishing.

Jeffrey, T. B. (1989). Issues regarding confidentiality for military psychologists. Military Psychology, 1, 49–56.

Jeffrey, T. B., Rankin, R. J., & Jeffrey, L. K. (1992). In service of two masters: The ethical–legal dilemma faced by military psychologists. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 16, 385–397.

Johnson, W. B. (1995). Perennial ethical quandaries in military psychology: Toward American Psychological Association & Department of Defense collaboration. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 26, 281–287.

Johnson, W. B. (2008). Top ethical challenges for military clinical psychologists. Military Psychology, 20, 49–62.

Johnson, W. B., Ralph, J., & Johnson, S. J. (2005). Managing multiple roles in embedded environments: The case of aircraft carrier psychology. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 36, 73–81.

Kalbeitzer, R. (2009). Psychologists and interrogations: Ethical dilemmas in times of war. Ethics & Behavior, 9(2), 156–168.

Kassin, S. M. (2014). False confessions: Causes, consequences, and implications for reform. Policy Insight from the Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 1, 112–121.

Kennedy, C. H., & Johnson, W. B. (2009). Mixed agency in military psychology: Applying the American Psychological Association ethics code. Psychological Services, 6(1), 22–31.

Kitaeff, J. (2011). Handbook of police psychology. New York: Routledge.

Lauritzen, P. (2013). The ethics of interrogation: Professional responsibility in an age of terror. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press.

Lifton, R. J. (2004). Doctors and torture. New England Journal of Medicine, 351, 415–416.

LoCicero, A. (2017). Military psychologist: An oxymoron. In C. E. Stout (Ed.), Terrorism, political violence, and extremism: New psychology to understand, face, and defuse the threat (pp. 309–329). Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO.

Loftus, E. F. (2011). Intelligence gathering post-9/11. American Psychologist, 66, 532–541.

Marks, J. H. (2005). Doctors of interrogation. Hastings Center Report, 35, 17–22.

Mayer, J. (2005). The experiment. The New Yorker. Retrieved from http://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2005/07/11/the-experiment-3

Meissner, C. A., Oleszkiewicz, S., Surmon-Böhr, F., & Alison, L. J. (2017). Developing an evidence-based perspective on interrogation: A review of the U.S. government’s High-Value Detainee Interrogation Group Research Program. Psychology, Public Policy, and Law, 23, 438–437.

Melton, G. B., Petrila, J., Poythress, N. G., & Slobogin, C. (2007). Psychological evaluations for the courts (3rd ed.). New York: Guilford.

Milgram, S. (1963). Behavioral study of obedience. Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 67, 371–378.

Mitchell, J. E., & Harlow, B. (2016). Enhanced interrogation: Inside the minds and motives of the Islamic terrorists who are trying to destroy America. New York: Crown Forum.

Morgan, C. A., Rabinowitz, Y. G., Hilts, D., Weller, C. E., & Coric, V. (2013). Efficacy of modified cognitive interviewing, compared to human judgments in detecting deception related to bio-threat activities. Journal of Strategic Security, 6, 100–119.

Porter, S., Rose, K., & Dilley, T. (2016). Enhanced interrogations: The expanding roles of psychology in police investigations in Canada. Canadian Psychology, 57(1), 35–43.

President of the United States. (2002). Human treatment of Al Qaida and Taliban detainees. White House Memo, Washington, DC: Author.

Reese, J. T. (1995). A history of police psychological services. In M. I. Kurke & E. M. Serivner (Eds.), Police psychology into the 21st century (pp. 31–44). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Reese, J. T., & Horn, T. (1988). Police psychology: Operational assistance. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Justice, Federal Bureau of Investigations.

Risen, J. (2014). Pay any price: Greed, power and endless war. New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

Rowe, K. L., Gelles, M. G., & Palarea, R. E. (2006). Crisis and hostage negotiations. In C. H. Kennedy & E. A. Zillmer (Eds.), Military psychology: Clinical and operational applications (pp. 310–330). New York: Guilford.

Sabourin, M. (2007). The assessment of credibility: An analysis of truth and deception in a multiethnic environment. Canadian Psychology, 48(1), 24–31.Senate Armed Services Committee. (2008). Inquiry into the treatment of detainees in U.S. custody. Washington, DC: Author.

Staal, M. A. (2017). Behavioral science consultation to interrogation and detention activities: Science, ethics & operations. A paper presented at the annual meeting of the American Psychological Association, Washington, D.C.

Staal, M. A. (2018). Applied psychology under attack: A response to the Brookline principles. Peace and Conflict: Journal of Peace Psychology, 24(4), 439–447.

Staal, M. A., & King, R. E. (2000). Managing a dual relationship environment: The ethics of military psychology. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 31, 698–705.

United States Congress. (2001). Authorization for use of military force. 50 USC 1541, Public Law 107–40. U.S. 107th Congress, joint resolution. Washington, DC: Author.

United States Congress. (2005). Detainee Treatment Act. Public Law 109–148, div. A, tit. X, §§ 1001–1006, 119 Statute 2680, 2739–44. Washington, DC: Author.

United States Congress. (2012). National defense authorization act. Public Law 112–81, as amended through P.L. 115–91, enacted December 12, 2017. Washington, DC: Author.

United States Congress. (2014). The Military Commissions Act of 2009 (MCA 2009): Overview and legal issues. Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service.

United States Supreme Court. (1966). Miranda v. Arizona. 384 U.S. 436. Retrieved from https://www.loc.gov/item/usrep384436

United States Supreme Court. (2004). Hamdi et al. v. Rumsfeld, Secretary of Defense, et al. Retrieved from https://www.supremecourt.gov/opinions/03pdf/03-6696.pdf

Vrij, A., Mann, S., & Leal, S. (2013). Deception traits in psychological interviewing. Journal of Police and Criminal Psychology, 28, 115–126.

Zimbardo, P. G. (1971). The power and pathology of imprisonment. Congressional Record. (Serial No. 15, October 25, 1971). Hearings before Subcommittee No. 3 of the Committee on the Judiciary, House of Representatives, 92d Congress. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office.