All that is necessary for evil to triumph is for good men to do nothing.

—Edmund Burke

Interrogation practices in the United States have long relied on customary knowledge—experiential-based knowledge uninformed by behavioral science (Hartwig, Meissner, & Semel, 2014). This reality was highlighted in a multiyear review of interrogation training and practice by the U.S. Intelligence Science Board (ISB) that described contemporary interrogation methods as lacking an evidence base (Fein, 2006) and called for the development of a research program to study ethical, science-based interrogation practices.

The ISB study advocated for what became the research program of the High-Value Detainee Interrogation Group (HIG), an interagency body founded by Executive Order 13491 in 2009 “to get the best intelligence possible based on scientifically proven methods and consistent with the Army Field Manual” (White House press briefing, August 24, 2009). A core responsibility of the HIG is “to study the comparative effectiveness of interrogation approaches and techniques, with the goal of identifying the existing techniques that are most effective and developing new lawful techniques to improve intelligence interrogations” (U.S. Department of Justice, Task Force on Interrogations and Transfer Policies, 2009).

Since it began operations in January 2010, the HIG research program has served as the center for advancing the science and practice of interview and interrogation within the U.S. government (for a review, see Meissner, Oleszkiewicz, Surmon-Böhr, & Alison, 2017). The program has taken a translational approach, supporting experimental research in the laboratory (e.g., Davis, Soref, Villalobos, & Mikulincer, 2016; Evans et al., 2013; Leins, Fisher, Pludwinsky, Robertson, & Mueller, 2014) and field observations and surveys of interrogation professionals regarding current practices (e.g., Alison, Alison, Noone, Elntib, & Christiansen, 2013; Kelly, Miller, & Redlich, 2015; Russano, Narchet, Kleinman, & Meissner, 2014). A priority of the HIG research program has been to test the efficacy of science-based interview methods under real-world conditions1 (Fallon & Brandon, in press). Such efficacy studies require collaborative partnerships that include practitioners who conduct interviews, researchers with expertise in the science of interviewing, and resources via government sponsorship. One such partnership—involving the HIG, the Air Force Office of Special Investigations (AFOSI), Roger Williams University (RWU), and Iowa State University (ISU)—is described here.

The HIG research program—which supports exclusively unclassified social and behavioral science research and adheres to international laws and U.S. federal code (45 CFR 46) pertaining to the protection of human subjects—has produced nearly 200 publications in peer-reviewed scientific journals on topics such as the role of rapport and information-gathering approaches (e.g., Alison et al., 2013; Evans et al., 2013), priming (e.g., Davis et al., 2016; Dawson & Hartwig, 2017; Dawson, Hartwig, Brimbal, & Denisenkov, 2017), interpreter-facilitated interviewing (e.g., Dhami, Goodman-Delahunty, Desai, 2017; Ewens et al., 2016; Houston, Russano, & Ricks, 2017), evaluation of the 2006 Army Field Manual interrogation approaches (e.g., Duke, Wood, Magee, & Escobar, 2018; Evans et al., 2014), cognitive approaches to credibility assessment (e.g., Vrij, Fisher, & Blank, 2017), the cognitive interview (e.g., Leins et al., 2014), evidence presentation (e.g., Luke et al., 2013), the Scharff Technique (e.g., Granhag, Oleszkiewicz, Strömwall, & Kleinman, 2015), error management in interviews (e.g., Oostinga, Giebels, & Taylor, 2018), ethics (e.g., Hartwig, Luke, & Skerker, 2017), language and cultural/ethnicity effects (Hwang & Matsumoto, 2014; Hwang, Matusmoto, & Sandoval, 2016), and sensemaking (Richardson, Taylor, Snook, Conchie, & Bennell, 2014). The HIG also has sponsored several studies on teaching the science-based methods to law enforcement and intelligence practitioners (e.g., Luke et al., 2016; Oleszkiewicz, Granhag, & Kleinman, 2017; Vrij, Leal, Mann, Vernham, & Brankaert, 2015).

The HIG training program was preceded by a two-year effort by HIG research program personnel to convey relevant behavioral science to HIG interrogators and analysts. At the invitation of the HIG, renowned psychologists traveled to Washington, D.C., to present brief lectures on topics such as stereotypes, the impact of isolation, and the science of teams. One- and two-day seminars were provided on the cognitive interview (Fisher & Geiselman, 1992), Strategic Use of Evidence (Hartwig, Granhag, Strömwall, & Kronkvist, 2006), principles of persuasion (Cialdini, 2001), and the Scharff Technique (Oleszkiewicz, Granhag, & Montecinos, 2014). In addition, the research team arranged for one-hour weekly meetings with the interrogators and analysts to review relevant psychological findings (e.g., social influence and principles of memory). While more than 100 hours of such seminars had been offered by December 2011, the research team found that this effort fell short of the intended objective as mission constraints limited practitioner attendance. In addition, while many practitioners found the training of real interest, they did not yet grasp the connection to their work.

A meeting was convened in mid-2012 to discuss how to proceed. Individuals with experience in interrogation training for U.S. military personnel and others with expertise in training UK police officers on the PEACE method (CPTU, 1992a, 1992b) provided advice. Two overarching themes emerged: (1) the training had to be relevant to the needs of the practitioners and (2) research scientists with no operational experience lacked the credibility necessary to maintain practitioners’ engagement. Fortunately, several practitioners with sufficient knowledge of the literature were available to serve as primary instructors of science-based methods. And rather than a scientist-practitioner model (e.g., Belar, 2000; Shapiro, 2002), the HIG adopted a joint (scientist+practitioner) model in which instruction was offered by practitioners who understood the science together with scientists who understood the challenges of the practice.2

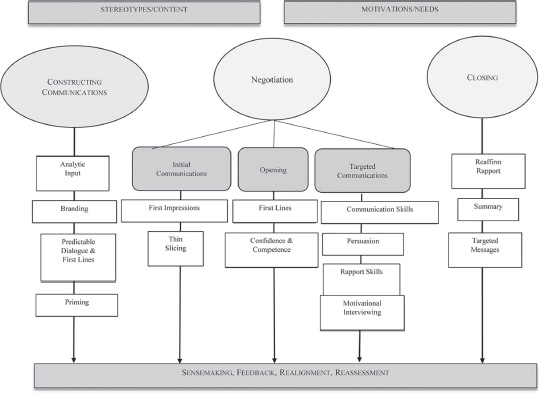

An initial training course was built on a framework previously developed to train hostage negotiators (Wells, 2014, 2015; Wells, Taylor & Giebals, 2013). The first phase of the framework (shown in Figure 12.1) includes such actions as deliberate planning, consideration of the negotiator’s “brand” (i.e., how he or she is perceived by the hostage taker), thoughtful scripting of the first words the negotiator will say to the subject and anticipation of what he or she might say in return, and how the interaction might be subtly influenced by verbal (Davis et al., 2016; Dawson, Hartwig, & Brimbal, 2015) or contextual (Dawson et al., 2017) priming. The negotiation itself was partitioned into initial communications, building on impression management (Leary & Kowalski, 1990) and “thin slicing” (Ambady & Rosenthal, 1992); opening, which was about initial dialogue and displaying confidence and competence (Cuddy, Fiske, & Glick, 2008), and targeted communication involving the use of persuasion tactics (Cialdini, 2001), building rapport (Rogers, 1951), and deploying components of motivational interviewing (MI; Miller & Rollnick, 1991, 2002). Ending or closing a negotiation required reaffirming rapport, summarizing what had been accomplished, and continuing with targeted messaging to further the negotiator’s position.

This framework was broadened to include both HIG program research findings and several decades of behavioral science specifically relevant to an interrogation, including memory-related issues (memory retrieval effects, including misinformation effects [e.g., Loftus & Zanni, 1975] and false memories [Loftus, 1979]), methods of eliciting a narrative (Fisher & Geiselman, 1992), and cognition-based approaches to assessing the validity of a narrative (Vrij et al., 2017; for a more detailed description of this HIG framework, see Brandon, Wells, & Seale, 2017).

The first course offered by the HIG in November 2012 was three and one-half weeks long. It included simulated interviews at the end of each week where students practiced the methods they had learned. Experts in adult learning assisted in creating support materials and providing feedback to the instructors on teaching skills. The students included HIG personnel who would benefit from understanding science-based methods.

The course subsequently was shortened to one week and offered several times a year to HIG staff as well as to those with whom the HIG might partner in the field (e.g., DoD interrogators, FBI agents, and members of local law enforcement agencies serving on federal counterterrorism task forces). The in-house training was soon augmented by courses taught at locations around the country. As of October 2017, the HIG had trained individuals from more than 50 U.S. government agencies, including more than 800 interrogation professionals, analysts, and interpreters in 2017 alone (Remarks of FBI Director Christopher Wray, 2017). The HIG offered this course at no cost to participants, and demand for the training grew beyond what could be supported.

Concurrent with the one-week course offering, the HIG research team continued to invite researchers to brief the HIG on their research findings. Using a “Research to Practice” (R2P) model, the HIG research and training teams worked with the scientists to ensure their presentations were accessible to HIG practitioners. These R2Ps provided a venue for more in-depth instruction on some of the topics introduced in the one-week course, such as Strategic Use of Evidence (Hartwig et al., 2005), the Scharff Technique (Granhag et al., 2015), the cognitive interview (Fisher & Geiselman, 1992), cognition-based credibility assessment (Vrij et al., 2017), and cross-cultural negotiation (Gelfand & Dyer, 2000). Over time, aspects of these R2Ps were incorporated into the HIG’s one-week course.

Having researchers supplement the instructor staff not only enhanced the value of the training, but it also offered researchers an opportunity for exposure to the practitioners. The operations of the HIG are classified, and almost all the participants in the HIG core course and the R2Ps worked in classified settings. Given that HIG scientists generally did not have a security clearance, the wall between science and practice was substantial and had an unfortunate effect: practitioners were unable to describe their operational challenges in detail nor were they able to share how the methods drawn from research were being employed in the field.3 However, in the R2P setting, the practitioners were able to share their challenges without providing classified details, and the researchers were able to participate in the unclassified simulated interrogation scenarios where their methods were employed. In the end, researchers also came away from an R2P with a better understanding of the operational context, which helped generate ideas for further research.

By 2015, the HIG one-week course had been redesigned to include more of the HIG-sponsored research findings, but this led to a difficulty in balancing the materials and skills to be presented with what could be reasonably assimilated in a single week (the period of time available given operational requirements). The final framework for the HIG course is shown in Figure 12.2 (redrawn from Brandon et al., 2017). As can be seen, this framework also began with preparation and analysis and then proceeded to instruction on active listening (Royce, 2005; Wells et al., 2013) and how to identify and mitigate resistance. The interview methods were rapport-based (e.g., Alison, et al., 2013), and situated in best practices for information elicitation (e.g., Fisher & Geiselman, 1992), using open-ended questioning tactics and credibility assessment (e.g., Vrij, 2000). The framework also contained modules that introduced topics for which more advanced (R2P) training was available, including the aforementioned Strategic Use of Evidence and cognitive interview.

The participants strongly advocated for a longer course, while adult learning advisors concurred that too many topics were covered. At the same time, the framework represented many specialized research domains with minimal cross-domain collaboration, and this complexity made it difficult for practitioners (and researchers) to grasp how the processes interacted.

The National Security Council, Department of Justice, and Congress provide oversight for the HIG (High-Value Detainee Interrogation Group, 2015), and it is reasonable for representatives of these bodies to inquire about the utility of the HIG methods in the field. Until 2016, the only evidence was anecdotal from trained practitioners, which was archived and, in some instances, reported in the press (e.g., Kolker, 2016). The HIG research team made a concerted effort to help the oversight agencies understand the inherent challenges in answering their question empirically, the problems associated with notoriously unreliable self-reporting (e.g., Nisbett & Wilson, 1977), the obstacles arising from reporting about HIG operations (which are classified), and the prohibitions against research involving detainees.

Still, the HIG research program had set a goal to conduct efficacy studies of the field applications of HIG research and the methods taught in the one-week course. Until 2015, however, this was not possible. First, although initially offered in an unclassified setting, the one-week course came to require a SECRET-level security clearance, not because the content of the course was classified but because participants felt they were unable to share their operational experiences in an unclassified setting. In addition, many course participants came from military or intelligence communities that did not provide those outside their own agencies with access to interviews conducted by their personnel. Third, DoD policy (DoD Instruction 3216.02, Protection of Human Subjects and Adherence to Ethical Standards in DoD-Supported Research) prohibits any kind of research on detainees, as defined in DoD Directive 2310.01E (Reference (p)). Finally, HIG research personnel lacked the resources required to conduct an efficacy study on its own. Under these conditions, it was clear that partnerships were needed. One such opportunity presented itself when a federal investigative agency charged with mitigating sexual assaults within the U.S. military sought to enhance its interviewing model to better serve that mission.

The DoD conducted its first in-depth survey on sexual harassment in 1988 (Task Force Report, 2004), followed by similar studies conducted by an array of government agencies. In 2004, in response to reports of an increasing number of sexual assaults, then-secretary of defense Donald Rumsfeld directed a review of the DoD process for the treatment and care of victims of sexual assault in the military services (DoD Memorandum, 2004). The Sexual Assault Response and Prevention Office (SARPO) was established (DoD Instruction, 2013) to ensure that each service complied with DoD-wide policies, including standards and training for healthcare personnel, options for reporting sexual assault, and eligibility standards for healthcare providers to perform sexual assault forensic examinations (DoD Instruction).

According to a 2016 report, 6,083 complaints had been filed in 2015. Of those, 1,500 involved a victim who reported an assault, asked for healthcare and victim support services, but refused to participate in any criminal investigation (Tilghman, 2016). Of the 4,584 cases where victims were willing to participate in a prosecution, 770 were dismissed by commanders who determined insufficient evidence existed to pursue the case. Of the 543 cases that eventually went to court-martial, 130 resulted in not-guilty verdicts. Of those that were convicted at court-martial, 161 resulted in charges unrelated to assault, while only 254 cases (4% of complaints filed) resulted in a service member being convicted of a sexual assault–related offense (Tilghman, 2016).

The Air Force Office of Special Investigations (AFOSI) provides criminal investigation and counterintelligence services to commanders throughout the air force. To preserve its investigative independence, the agency reports to the inspector general of the air force. AFOSI operates worldwide from over 250 field units, with 2,000 military and civilian credentialed special agents, 1,000 professional and military staff who provide operational support, and 400 air force reservists (each category including officers and enlisted personnel). All new special agent recruits go through an 11-week, entry-level training course at the Federal Law Enforcement Training Center (FLETC) in Glynco, Georgia, followed by an 8-week advanced course that is AFOSI-specific.

All agents begin their careers as criminal investigators before specializing in other mission areas (e.g., counterintelligence). They gain experience interviewing victims, witnesses, sources, and subjects (suspects) for a broad range of criminal investigations, including sex offenses (approximately 49% of AFOSI criminal cases in 2017); drug violations (35%); death investigations (7%) and crimes against persons, property, or society (9%). Each type of investigation requires relationship-building, adaptive communication, and effective interviewing skills.

AFOSI has long utilized specially trained psychologists as consultants. The Behavioral Sciences Directorate consists of a multidisciplinary team of psychologists and behavioral science experts who provide direct consultation to criminal investigations, counterintelligence operations, counterterrorism, special agent-training, assessment and selection, operational performance, and personnel resilience. In recent years, its role in agent-training has grown significantly and includes topics in nearly every aspect of investigations and operations, most notably in the areas of sex crimes investigations, eyewitness memory, victimology, investigative decision making, influence, and advanced interviewing techniques. AFOSI psychologists have maintained a strong standing within the agency as subject matter experts, in part due to their reputation for applying the latest scientific research and evidence-based methods when supporting complex investigative questions.

As DoD was addressing the need to improve its sexual assault prevention and response processes, AFOSI recognized it needed to improve its method for interviewing victims, using a rapport-based approach that would increase the quantity and quality of information obtained. The agency also recognized it needed to better educate its investigators on sexual assault matters, including gaining a greater understanding of victim experiences, memory, cognitive biases, stereotypes, and trauma. AFOSI looked to its psychologists to find the best interview method and to help develop a new advanced Sex Crimes Investigations Training Program (SCITP). After exhaustive research and consultation with experts, the cognitive interview (Fisher & Geiselman, 1992) was selected as the agency’s method for interviewing victims of sexual assault, and this was incorporated into the two-week course from its inception in 2012.

AFOSI investigators consistently reported that the cognitive interview improved the effectiveness of their sexual assault investigations, a view supported by compelling case examples and anecdotes that illustrated successful investigative outcomes. No structured data was collected, however, to empirically assess improved effectiveness. Nonetheless, the reported successes led some AFOSI agents to begin using the technique with other victims and witnesses. One of the most significant effects of the method’s reported success with victim interviews was a greater openness among senior agency leadership and field agents alike to explore new techniques. AFOSI’s public commitment in 2012 to support evidence-based methods, reinforced by the success of the cognitive interview with victims and witnesses, opened the door to the next logical step forward. Specifically, AFOSI psychologists began to challenge the effectiveness of traditional confrontational law enforcement methods for interviewing suspects as compared to rapport-based, non-confrontational methods such as the cognitive interview. This evidence-based focus led AFOSI to approach the HIG and propose a training-research partnership.

The HIG convened a two-day meeting with AFOSI and several HIG-sponsored researchers and experienced practitioners in the summer of 2014 to articulate the requirements of AFOSI agents and discuss the protocols and logistics of data collection. The plan that emerged after subsequent reviews at both the HIG and AFOSI called for four 1-week courses to be offered over a period of several months to 120 AFOSI agents, with each attendee providing one pre- and one post-training video recording of a suspect interview they had conducted. These records would be assessed for whether the agent used the science-based or traditional methods and for the impact of those methods of information collection.

A primary concern of both parties was data protection. The plan that was adopted—which would ensure the efficacy study research team would not be privy to any personally identifiable information (PII)—entailed a process whereby AFOSI would have the video recordings of agents’ interviews transcribed, with all PII and sensitive information removed. These transcripts then served as the data for the research team. Following proper procedure, human subjects research protocols for the project were submitted to and approved by both university institutional review boards (IRBs) and the FBI’s IRB.

At the request of AFOSI, the one-week HIG course was modified somewhat to allow for greater emphasis on the cognitive interview (the framework used in the course is shown in Figure 12.3). Given that AFOSI agents most often interview air force personnel, less emphasis was placed on persuasion tactics as the command structure leads the subject to be cooperative, even if not altogether truthful. A modified version of rapport-based questioning tactics (Alison et al., 2013) and sensemaking (Taylor, 2002) was emphasized as methods to develop cooperation and deal with resistance. In addition to the cognitive interview, methods of credibility assessment were included, such as eliciting verifiable facts (e.g., Nahari & Vrij, 2014), asking unanticipated questions (e.g., Vrij et al., 2009), imposing cognitive load (Vrij, Mann, & Fisher, 2012), using a model statement as a demonstration of level of detail (Leal, Vrij, Warmelink, Vernham & Fisher, 2015), and eliciting within-statement and evidence-statement inconsistencies and discrepancies with the Strategic Use of Evidence (SUE) technique (Hartwig et al. 2005).

HIG research personnel also participated in the courses, providing instruction, coaching practical exercises, and mentoring. Additional AFOSI psychologists (some of whom were teaching the cognitive interview in the AFOSI’s advanced Sex Crimes Investigation Training Program) were also present. The training itself included two or three practical exercises each day, as well as a full-day interview simulation on the final day.

The instructors found the AFOSI agents receptive despite the fact that the material being presented was often contrary to their previous training, which was a Reid-type model of accusatory and confrontational interviewing (see Meissner, Kelly, & Woestehoff, 2015). There were always a few attendees who were reluctant to engage, but the course schedule included strategically planned exercises that were persuasive. One was an observation challenge that involved an individual (one not associated with the course) who would briefly enter the classroom and engage with the instructor. This interruption was surreptitiously video recorded for later referral during a discussion on memory and the importance of eliciting a detailed narrative. Most of the agents—who viewed themselves as “expert witnesses”—incorrectly reported many of the salient details about this staged event. This experience frequently promoted a more open-minded reception and encouraged a more collegial relationship between instructors and the previously resistant students.

A sample of 69 interrogations from 51 different investigators were eventually submitted for analysis. Fifty of the interrogations were conducted prior to training, while 19 were conducted post-training. Eighteen investigators were represented with a complete pre- and post-training set of interviews. In all cases the transcripts were anonymized prior to providing them to the research team for analysis. All coders received extensive training on the science-based interviewing and interrogation methods presented during the course, as well as on traditional accusatorial interrogation methods (Inbau, 2013). Coders were introduced to each element of the training by reviewing materials that described the approaches and discussing key constructs with the lead researchers. Sample interviews were then used to facilitate application of the material and to align coders with respect to the items they would be evaluating. Appropriate steps were taken to establish acceptable levels of interrater reliability.

Coders evaluated each transcript for the use of Reid-like accusatorial approaches, active listening skills, investigator talking time, cognitive interview techniques, and rapport-based techniques. Transcripts were also coded for perceived MI rapport (i.e., empathy, autonomy, evocation, adaptation, acceptance), the presence of suspect counter-interrogation strategies (e.g., monosyllabic responses, silence, rehearsed responses), and relevant outcome measures that included suspect cooperativeness, the amount of information disclosure (level of detail, forthcomingness, completeness), and whether the subject provided incriminating statements (including full confessions and partial admissions). Analysis of the results controlled for both course iteration and variance, attributable to interrogators over time.

Compared to pre-training, investigators increased their use of active listening skills, d = 1.15 [0.59, 1.71], and cognitive interviewing techniques, d = 1.62 [1.03, 2.22]. This is consistent with finding a significant increase in perceived MI rapport, d = 0.90 [0.35, 1.45], and a significant decrease in investigator talking time, d = 0.49 [0.04, 0.94], from pre- to post-training. However, there were no training effects on the use of rapport-based tactics, evidence presentation strategies, or accusatorial techniques (Russano, Meissner, Atkinson, & Dianiska, 2017).

With respect to the effects of training on key outcome variables, no differences in suspect counter-interrogation strategies were observed. Conversely, there was a significant increase in observed rapport with the subject, d = 0.90 [0.35, 1.45]; a marginally significant increase in suspect cooperativeness, d = 0.48 [-0.05, 1.02], p = .07; and a significant increase in information disclosure, d = 0.92 [0.37, 1.47], from pre- to post-training. Although not reaching conventional significance levels, the likelihood of a suspect providing a full confession increased from 30 percent to 47 percent post-training.

To understand the relationships between interviewing methods, perceived MI rapport, and cooperation and information gain, a mediational path model that controlled for the training effects noted earlier was proposed. Overall, the model provided a good fit to the data and accounted for 41 percent of the variance in cooperation-resistance, and 48 percent of the variance in information gain. As shown in Figure 12.4, active listening skills, cognitive interviewing techniques, and rapport-based tactics both directly increased perceived MI rapport and indirectly increased information elicitation via cooperation. Perceived MI rapport directly increased suspect cooperation, and cooperation directly predicted increased information gain. The positive effects and expected relationships between interview techniques, perceived rapport, and ultimately cooperation and information disclosure confirmed the scientific efficacy of the tactics in an operational context.

In contrast to these positive effects of the science-based model, the use of accusatorial techniques increased suspects’ use of counter-interrogation strategies, which reduced cooperation and, indirectly, information gain. While the training was not designed to encourage the disuse of accusatorial tactics, the modeling data suggests accusatorial tactics run counter to the goals of a successful interrogation. These results are consistent with data obtained from interrogations in notably different contexts (e.g., homicide interrogations [Kelly et al., 2015] and criminal interviews of terrorist suspects [Alison et al., 2013, 2014]), where interview approaches broadly described as rapport-based and information-gathering were shown to increase cooperation and, in turn, the amount of information yielded by the subjects. The pattern also is consistent with experimental assessments comparing information-gathering and accusatorial tactics (Evans et al., 2013; Meissner et al., 2014; Meissner, Russano, & Atkinson, 2017).

This effort provided a unique opportunity to demonstrate that the HIG framework was making a positive difference: training resulted in an increased use of science-based interview methods, and the use of science-based interview methods resulted in increased information yield. The HIG had been mandated to compare the effectiveness of interrogation approaches and develop “new lawful techniques to improve intelligence interrogations” (U.S. Department of Justice, Task Force on Interrogations and Transfer Policies, 2009), and the partnership with AFOSI was viewed as a step toward fulfilling that requirement. In addition, despite administrative challenges, the effectiveness of the HIG/AFOSI partnership enabled the HIG research program to prioritize additional similar efforts, some of which began in 2017 with the Los Angeles Police Department (which had been supporting HIG research since 2013; see Kelly et al., 2015), the Tempe Police Department, the Department of Homeland Security Immigration & Customs Enforcement, and the New York City Police Department.

By the end of 2015, AFOSI began modifying some of the content of existing advanced courses for agents, incorporating components of the HIG/AFOSI course. The advanced general crimes investigations course (AGCIC), for example, added the cognitive interview and blocks on rapport-based tactics, eyewitness memory, and dispelling misconceptions about credibility assessment (Davis, 2018). AGCIC was the first AFOSI-taught course to teach a rapport-based (versus theme-based) method for interviewing suspects. In January 2017, all of AFOSI Training Academy instructors at FLETC were trained in the HIG framework. The AFOSI Academy immediately began development of a new two-week cognitive interviews and interrogations course—first presented in December 2017—which expanded on the HIG/AFOSI course to include more extensive practical exercises that involved realistic scenarios with actual eyewitnesses (Davis, 2018). Concurrently, the Academy began incorporating some of the material into the curriculum of AFOSI’s basic course and added the cognitive interview as the method for interviewing victims and witnesses. In May 2018, AFOSI conducted a curriculum review of the basic course and made the decision to replace the FLETC 5-Step method with the model introduced by the HIG/AFOSI partnership. This will require significant changes to training content, but AFOSI expects to begin training the model to new agents by 2019.

Data acquisition. One of the practical challenges of this project was the procurement of suspect interrogations recordings. Not all AFOSI investigators regularly conducted interrogations. Some interrogations did not fit the research criteria, and some investigators did not immediately archive their video records. Also, several of the recordings presented transcription difficulties because the interview was conducted in a foreign language or was of poor audio quality. As a result, the research team had fewer transcripts than planned, which limited what could be inferred from the data.

Consistency across courses. Given that the one-week course was offered over a series of months (September and November 2014, and February and March 2015), the instructors felt obliged to revise the course based on experiences with prior iterations and as their having grown more familiar with the AFOSI mission. A discussion of customary interrogation tactics, such as those taught at the Reid school (Inbau, 2013), was added after the first iteration. There were also changes in the composition of the support staff—to include AFOSI psychologists and HIG-sponsored researchers—across the courses. Many of these individuals acted as coaches during the practical exercises, so these changes likely influenced the instruction across iterations. While such variance was less than optimal, the research team was able to control for the various course iterations in their analysis of the data, and it was the collective judgment of the HIG/AFOSI team that providing the best possible instruction was more important than a strict adherence to a research protocol.

Training limitations. Not all AFOSI agents attended the course. In many instances, a single agent would attend the training from a field office with multiple agents assigned. This meant the trained agent would return to an office where traditional interview methods remained the standard and the agent could not deploy the team-based HIG model. Given this challenge—and the inherent restraints of one-time training (Salas, Tannenbaum, Kraiger, & Smith-Jentsch, 2012)—it would have been more effective to train both field agents and their supervisors, and to also provide follow-on mentoring to sustain buy-in from senior management.

It’s not an intelligence interview. The HIG’s primary collection requirements focus on intelligence rather than criminal justice. Some within the Intelligence Community have questioned the usefulness of studying criminal interrogations to better understand intelligence interrogations. The differences between these contexts has been described elsewhere (Evans, Meissner, Brandon, Russano, & Kleinman, 2010), and while there are significant differences, both maintain the goal of eliciting cooperation and information. The primary goal of the HIG/AFOSI training was to enhance information yield, not elicit confessions. The argument was made to trainees that information gain should be the primary goal of an interrogation, and even where a confession is offered, additional information to support the admission will further advance the investigation (e.g., Davis & Leo, 2006).

Scientist+practitioner. Changing the content and culture of criminal and intelligence interrogation/interview training is a slow process given the diversity and complexity of practitioners, who range from well-trained intelligence officers to uniformed patrol officers. One aspect of the training model that proved consistently effective was an instructor cadre that offered the synergy of experienced practitioners with a strong knowledge of the science alongside scientists with experience working with intelligence and law enforcement professionals. Moreover, speaking with a single, evidence-based “voice” added a strong measure of credibility that ultimately earned the respect of the trainees. In short, the multidisciplinary, scientist+practitioner model worked well to bridge the divide between the researcher and practitioner communities.

AFOSI Fact Sheet. (2018). Retrieved from http://www.osi.af.mil/About/Fact-Sheets/Display/Article/349945/air-force-office-of-special-investigations/

Alison, L., Alison, E., Noone, G., Elntib, S., & Christiansen, P. (2013). Why tough tactics fail and rapport gets results: Observing Rapport-Based Interpersonal Techniques (ORBIT) to generate useful information from terrorists. Psychology, Public Policy, and Law, 19, 411–431. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0034564

Alison, L., Alison, E., Noone, G., Elntib, S., Waring, S., & Christiansen, P. (2014). The efficacy of rapport-based techniques for minimizing counter-interrogation tactics amongst a field sample of terrorists. Psychology, Public Policy, and Law, 20, 421–430. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/law0000021

Ambady, N., & Rosenthal, R. (1992). Thin slices of expressive behavior as predictors of interpersonal consequences: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 111, 256–274.

Belar, C. D. (2000). Scientist-practitioner ≠ science + practice: Boulder is bolder. American Psychologist 55(2), 249–250.

Brandon, S. E., Wells, S., & Seale, C. (2017). Science-based interrogations: Eliciting information. Journal of Investigative Psychology and Offender Profiling, 15(2). https://doi.org/10.1002/jip.1496

Cialdini, R. B. (2001). Influence: Science and practice (3rd ed.). Boston, MA: Pearson Education.

CPTU (Central Planning and Training Unit). (1992a). A guide to interviewing. Harrogate, UK: Home Office.

CPTU (Central Planning and Training Unit). (1992b). The Interviewer’s rule book. Harrogate, UK: Home Office.

Cuddy, A. J., Fiske, S. T., & Glick, P. (2008). Warmth and competence as universal dimensions of social perception: The stereotype content model and the BIAS map. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 40, 61–149.

Davis, B. J. (2018). No detail too small. AFOSI evolves interviewing practices to effectively gain better information. Airman (April 9). Retrieved from http://airman.dodlive.mil/2018/04/09/no-detail-too-small/

Davis, D., & Leo, R. (2006). Strategies for preventing false confessions and their consequences. In M. Kebbell & G. Davies (Eds.), Practical psychology for forensic investigations and prosecutions (pp. 121–149). Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons Ltd.

Davis, D., Soref, A., Villalobos, J. G., & Mikulincer, M. (2016). Priming states of mind can affect disclosure of threatening self-information: Effects of self-affirmation, mortality salience, and attachment orientations. Law and Human Behavior, 40, 351–361. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/lhb0000184

Dawson, E., & Hartwig, M. (2017). Rethinking the interview room: Promoting disclosure and rapport through priming. Polygraph, 46(2), 132–145.

Dawson, E., Hartwig, M., & Brimbal, L. (2015). Interviewing to elicit information: Using priming to promote disclosure. Law and Human Behavior, 39, 443–450. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/lhb0000136

Dawson, E., Hartwig, M., Brimbal, L., & Denisenkov, P. (2017). A room with a view: Setting influences information disclosure in investigative interviews. Law and Human Behavior. 41(4), 333–343. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/lhb0000244

Dhami, M. K., Goodman-Delahunty, J., & Desai, S. (2017). Development of an information sheet providing rapport advice for interpreters in police interviews. Police Practice and Research, 18(3), 291–305.

DoD Instruction. (2013). Sexual Assault Prevent and Response (SABR) Program Procedures (March 28, 213). Department of Defense, Washington DC.

DoD Memorandum. (2004). Memorandum for the Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense (Force Health Protection and Readiness), Feb. 10, 2004. Under Secretary of Dense, Pentagon, Washington, DC.

Duke, M. C., Wood, J. M., Magee, J., & Escobar, H. (2018). The effectiveness of army field manual interrogation approaches for educing information and building rapport. Law and Human Behavior, 42, 442–437. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/lhb0000299

Evans, J. R., Houston, K. A., Meissner, C. A., Ross, A. B., LaBianca, J. R., Woestehoff, S. A., & Kleinman, S. M. (2014). An empirical evaluation of intelligence-gathering interrogation techniques from the United States Army field manual. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 28, 867–875. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/acp.3065

Evans, J. R., Meissner, C. A., Brandon, S. E., Russano, M. B., & Kleinman, S. M. (2010). Criminal versus HUMINT interrogations: The importance of psychological science to improving interrogative practice. The Journal of Psychiatry & Law, 38(1–2), 215–249.

Evans, J. R., Meissner, C. A., Ross, A. B., Houston, K. A., Russano, M. B., & Horgan, A. J. (2013). Obtaining guilty knowledge in human intelligence interrogations: Comparing accusatorial and information-gathering approaches with a novel experimental paradigm. Journal of Applied Research in Memory & Cognition, 2, 83–88.

Ewens, S., Vrij, A., Leal, S., Mann, S., Jo, E., & Fisher, R. P. (2016). The effect of interpreters on eliciting information, cues to deceit and rapport. Legal and Criminological Psychology, 21(2), 286–304.

Fallon, M., & Brandon, S. E. (in press). The HIG Project: the road to scientific research on interrogation. In S. J. Barela, M. Fallon, G. Gaggioli, & J. D. Ohlin (Eds.), Interrogation and torture: Research on efficacy and its integration with morality and legality. Bethesda, MD: Oxford University Press.

Fein, R. (2006). Introduction. In educing information: Interrogation: Science and art. Intelligence Science Board Phase 1 Report (pp. 1–6). Washington, DC: National Intelligence College Press.

Fisher, R. P., & Geiselman, R. E. (1992). Memory-enhancing techniques in investigative interviewing: The Cognitive interview. Springfield, IL: C.C. Thomas.

Gelfand, M., & Dyer, N. (2000). A cultural perspective on negotiation: Progress, pitfalls, and prospects. Applied Psychology, 49(1), 62–99.

Granhag, P. A., Oleszkiewicz, S., Strömwall, L. A., & Kleinman, S. M. (2015). Eliciting intelligence with the Scharff technique: Interviewing more and less cooperative and capable sources. Psychology, Public Policy, and Law, 21, 100–110. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/law0000030

Hartwig, M., Granhag, P. A., Strömwall, L. A., & Kronkvist, O. (2006). Strategic use of evidence during police interviews: When training to detect deception works. Law and Human Behavior, 30, 603–619.

Hartwig, M., Granhag, P. A., Strömwall, L. A., & Vrij, A. (2005). Detecting deception via strategic disclosure of evidence. Law and Human Behavior, 29(4), 469–484.

Hartwig, M., Luke, T. J., & Skerker, M. (2017). Ethical perspectives on interrogation: An analysis of contemporary techniques. In J. Jacobs & J. Jackson (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of criminal justice ethics (pp. 326–347). New York: Routledge.

Hartwig, M., Meissner, C. A., & Semel, M. D. (2014). Human intelligence interviewing and interrogation: Assessing the challenges of developing an ethical, evidence-based approach. In R. Bull (Ed.), Investigative interviewing (pp. 209–228). New York: Springer. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4614-9642-7_11

High-Value Detainee Interrogation Group. (2015). Retrieved from https://www.fbi.gov/about/leadership-and-structure/national-security-branch/high-value-detainee-interrogation-group

Houston, K. A., Russano, M. B., & Ricks, E. P. (2017). “Any friend of yours is a friend of mine”: Investigating the utilization of an interpreter in an investigative interview. Psychology, Crime & Law, 23(5), 413–426.

Hwang, H. C., & Matsumoto, D. (2014). Sender ethnicity differences in lie detection accuracy and confidence. GSTF Journal of Law and Social Sciences, 3, 15–19. http://dx.doi.org/10.7603/s40741-014-0001-6

Hwang, H. C., Matsumoto, D., & Sandoval, V. (2016). Linguistic cues of deception across multiple language groups in a mock crime context. Journal of Investigative Psychology and Offender Profiling, 13, 56–69. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/jip.1442

Inbau, F. E. (2013). Essentials of the Reid technique. Burlington MA: Jones & Bartlett Publishers.

Kelly, C. E., Miller, J. C., & Redlich, A. D. (2015). The dynamic nature of interrogation. Law and Human Behavior, 40, 295–309.

Kolker, R. (2016). A severed head, two cops, and the radical future of interrogation. Wired Magazine, May 24, 2018. Retrieved from https://www.wired.com/2016/05/how-to-interrogate-suspects/

Leal, S., Vrij, A., Warmelink, L., Vernham, Z., & Fisher, R. P. (2015). You cannot hide your telephone lies: Providing a model statement as an aid to detect deception in insurance telephone calls. Legal and Criminological Psychology, 20(1), 129–146.

Leary, M. R., & Kowalski, R. M. (1990). Impression management: A literature review and two-component model. Psychological Bulletin, 107(1), 34–47.

Leins, D., Fisher, R. P., Pludwinsky, L., Robertson, B., & Mueller, D. H. (2014). Interview protocols to facilitate human intelligence sources’ recollections of meetings. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 28, 926–935. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/acp.3041

Loftus, E. F. (1979). The malleability of human memory. American Scientist, 67, 312—320.

Loftus, E. R., & Zanni, G. (1975). Eyewitness testimony: The influence of the wording of a question. Bulletin of the Psychonomic Society, 5, 86–88.

Luke, T. J., Hartwig, M., Brimbal, L., Chan, G., Jordan, S., Joseph, E., … Granhag, P. A. (2013). Interviewing to elicit cues to deception: Improving strategic use of evidence with general-to-specific framing of evidence. Journal of Police and Criminal Psychology, 28, 54–62. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11896-012-9113-7

Luke, T. J., Hartwig, M., Joseph, E., Brimbal, L., Chan, G., Dawson, E., … & Granhag, P. A. (2016). Training in the strategic use of evidence technique: Improving deception detection accuracy of American law enforcement officers. Journal of Police and Criminal Psychology, 31, 270–278. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11896-015-9187-0

Meissner, C. A., Kelly, C. E., & Woestehoff, S. A. (2015). Improving the effectiveness of suspect interrogations. Annual Review of Law & Social Sciences, 11, 211–233. doi: 10.1146/annurev-lawsocsci-120814–121657

Meissner, C. A., Oleszkiewicz, S., Surmon-Böhr, F., & Alison, L. J. (2017). Developing an evidence-based perspective on interrogation: A review of the U.S. government’s High-Value Detainee Interrogation Group Research Program. Psychology, Public Policy, and Law, 23, 438–437.

Meissner, C. A., Redlich, A. D., Michael, S. W., Evans, J. R., Camilletti, C. R., Bhatt, S., & Brandon, S. (2014). Accusatorial and information-gathering interrogation methods and their effects on true and false confessions: A meta-analysis review. Journal of Experimental Criminology, 10(4), 459–486. doi:10.1007/s11292–014–9207.6

Meissner, C. A., Russano, M. B., & Atkinson, D. (2017, January). Science-based methods of interrogation: A training evaluation and field assessment. Paper presented at the Society for Applied Research in Memory & Cognition Conference, Sydney, Australia.

Miller, W. R., & Rollnick, S. (1991). Motivational interviewing: Preparing people to change addictive behavior. New York: Guilford Press.

Miller, W. R., & Rollnick, S. (2002). Motivational interviewing: Preparing people for change (2nd ed.). New York: Guilford Press.

Nahari, G., & Vrij, A. (2014). Can I borrow your alibi? The applicability of the verifiability approach to the case of an alibi witness. Journal of Applied Research in Memory and Cognition, 3, 89–94.

Nisbett, R. E., & Wilson, T. D. (1977). Telling more than we can know: Verbal reports on mental processes. Psychological Review, 84(3), 231–259.

Oleszkiewicz, S., Granhag, P. A., & Cancino Montecinos, S. (2014). The Scharff-technique: Eliciting intelligence from human sources. Law and Human Behavior, 38(5), 478–489.

Oleszkiewicz, S., Granhag, P. A., & Kleinman, S. M. (2017). Eliciting information from human sources: Training handlers in the Scharff technique. Legal and Criminological Psychology. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/lcrp.12108

Oostinga, M., Giebels, E., & Taylor, P. J. (2018). “An error is feedback”: The experience of communication error management in crisis negotiations. Police Practice and Research, 19(1), 17–30. DOI: 10.1080/15614263.2017.13 26007

Remarks of FBI Director Christopher Wray. (2017). HIG: Using science and research to combat national security threats. Seventh annual HIG Research Symposium. United States Institute of Peace, Washington, DC. Retrieved from https://www.fbi.gov/news/speeches/hig-using-science-and-research-to-combat-national-security-threats

Richardson, B. H., Taylor, P. J., Snook, B., Conchie, S. M., & Bennell, C. (2014). Language style matching and police interrogation outcomes. Law and Human Behavior, 38, 357–366. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/ lhb0000077

Rogers, C. (1951). Client-centered therapy. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin.

Royce, T. (2005). The negotiator and the bomber: Analyzing the critical role of active listening in crisis negotiation. Negotiation Journal, 21, 5–27. DOI: 10.1111/j.1571-.2005.00045.x

Russano, M. B., Meissner, C. A., Atkinson, D., & Dianiska, R. E. (2017, March). Training science-based methods of interrogation with Air Force Office of Special Investigations. Paper presented at the American Psychology-Law Society Conference, Seattle, WA.

Russano, M. B., Narchet, F. M., Kleinman, S. M., & Meissner, C. A. (2014). Structured interviews of experienced intelligence and military interrogators. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 28, 847–859. doi: 10.1002/acp.3069

Salas, E., Tannenbaum, Scott I., Kraiger, K., & Smith-Jentsch, K. A. (2012). The science of training and development in organizations: What matters in practice. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 13(2), 74–101. DOI: 10.1177/1529100612436661

Shapiro, D. (2002). Renewing the scientist-practitioner model. PSYCHOLOGIST-LEICESTER, 15(5), 232–235.

Task Force Report on Care for Victims of Sexual Assault. (2004). Retrieved from http://www.sapr.mil/public/docs/reports/task-force-report-for-care-of-victims-of-sa-2004.pdf

Taylor, P. (2002). A cylindrical model of communication behavior in crisis negotiation. Human Communication Research, 28, 7–48.

Tilghman, A. (2016). Military sex assault: Just 4 percent of complains result in convictions. Military Times, May 5, 2016. Retrieved from https://www.militarytimes.com/veterans/2016/05/05/military-sex-assault-just-4-percent-of-complaints-result-in-convictions/

U.S. Department of Justice, Task Force on Interrogations and Transfer Policies. (2009). Special task force on interrogations and transfer policies issues its recommendations to the president. Retrieved from https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/special-task-force-interrogations-and-transfer-policies-issues-its-recommendations-president

Vrij, A. (2000). Detecting lies and deceit: The psychology of lying and implications for professional practice. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons LTD.

Vrij, A., Fisher, R., & Blank, H. (2017). A cognitive approach to lie detection: A meta-analysis. Legal and Criminological Psychology, 22, 1–21. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/lcrp.12088

Vrij, A., Leal, S., Granhag, P., Mann, S., Fisher, R., Hillman, J., & Sperry, K. (2009). Outsmarting the liars: The benefit of asking unanticipated questions. Law and Human Behavior, 33, 159–166.

Vrij, A., Leal, S., Mann, S., & Fisher, R. (2012). Imposing cognitive load to elicit cues to deceit: Inducing the reverse order technique naturally. Psychology, Crime, & Law, 18, 579–594.

Vrij, A., Leal, S., Mann, S., Vernham, Z., & Brankaert, F. (2015). Translating theory into practice: Evaluating a cognitive lie detection training workshop. Journal of Applied Research in Memory and Cognition, 4(2), 110–120.

Vrij, A., Meissner, C. A., Fisher, R. P., Kassin, S. M., Morgan, C. A., III, & Kleinman, S. M. (2017). Psychological perspectives on interrogation. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 12(6), 927–955.

Wells, S. (2014). What communication skills are effective in dealing with antagonistic situations: A tale of two halves? Unpublished thesis, Lancaster University, UK.

Wells, S. (2015). Hostage negotiation and communication skills in a terrorist environment. In J. Pearse (Ed.), Investigating terrorism: Current political, legal, and psychological issues (pp. 144–167). New York: Wiley-Blackwell.

Wells, S., Taylor P., & Giebels, E. (2013). Crisis negotiation: From suicide to terrorism intervention. In M. Olekalns & W. Adair (Eds.), Handbook of negotiation research (pp. 473–498). Melbourne: Edward Elgar Publishing.

White House Press Briefing. (2009). Press briefing by deputy press secretary Bill Burton. Oaks Bluffs, MA. Retrieved from http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/index.php?pid=86562.