Chapter 10: The Rivers of Paradise

About an hour before sunset we reached Mongyu, a small Shan village at the point where the Ledo-Stilwell Road keyed into the old Burma Road, which led up from Mandalay. This was the focal point of the last great battle of the Burma campaign. After two months of continuous fighting, the battle had finally ended on January 27, 1945, when U.S., British, and Chinese forces forced the Japanese out of Mongyu and the surrounding region between the Shweli and Salween rivers.

This made possible the way from Burma into China, and the following day the first U.S. truck convoy rolled through Mongyu, having come down the Ledo-Stilwell Road from Ledo. It then continued along to the old Burma Road, heading for Kunming, thus opening up an overland route connecting unoccupied China with the sea. I’d seen a photograph of this historic event in the administrative building at Ledo, showing the first truck passing under an archway with two arrows pointing in opposite directions, one with the words BURMA: LEDO ROAD—LEDO 478 MILES, the other reading CHINA: BURMA ROAD—KUNMING 566 MILES. We were almost halfway there, and we’d soon be crossing the border into China. I’d had a bellyful of Burma, but I feared that China might be even worse.

At the U.S. Army camp at Mongyu, we were told that thousands of Japanese soldiers were still holed up in the mountains to the south, where they were probably starving to death, since all of their supply lines were now controlled by the Allies. They were still dangerous, though, for just a couple of days before they had ambushed a Chinese patrol sent south from Mongyu, and some of these casualties were undoubtedly those I’d seen earlier in the day.

We were all assigned watches on the defense perimeter around the camp that night, because Japanese stragglers had been caught as they attempted to sneak into the base under cover of darkness, trying to find food. They were desperate and dangerous, we were warned, and soldiers on sentry duty were ordered to fire without warning at any intruders. Kachin scouts would be interspersed with those of our unit who would be on duty, one of them positioned out of sight between each pair of us.

My watch was from midnight to four in the morning, and I was awakened by the captain of the watch, in this case one of our ensigns. He then woke up my pal Tunney King, and we met the Kachin scout who would be on sentry duty with us. Without speaking, the Kachin led us out into the moonless night to relieve those who were going off their watch.

It was pitch-dark when I got up to go to my sentry post. I was armed with my carbine and .45 pistol, as was Tunney, but the Kachin bore only his lethal-looking dau, which I noticed when he positioned me and Tunney in shallow foxholes. He then crawled out into the jungle somewhere between us. I could see neither him nor Tunney, though I sensed they were not far off to my left.

The only sounds were the startling birdcalls, the rustling of the trees and underbrush when a sudden breeze blew up, and the echoing howl of a lonely jackal from deep in the menacing jungle. I’d never felt so alone and vulnerable, and I worried that any moment someone would spring on me from the surrounding darkness.

Then, about halfway through my watch, I suddenly heard someone screaming in the darkness to my left. The scream continued for a few seconds, ending in a gurgling sound before it stopped abruptly. I was stiff with terror, and I held my rifle on the ready as I stared into the darkness, waiting for someone to emerge. But I saw nothing, and when my relief took over at four o’clock I returned to our tent, where Ed was still sound asleep.

At morning chow I saw Tunney and asked him if he knew what had happened in the middle of our watch, but he said it had been too dark to see anything. He had been too terrified to go and look, just as I’d been. There was no sign of the Kachin scout who had been on sentry duty with us, and so, on reflection, I figured that he had caught a Japanese soldier sneaking into our camp and had cut his throat, in which case he would have now added another pair of severed ears to his collection. I was horrified, though I knew that if the intruder had come at me I’d have had it, and at the mere thought of it I suffered a sudden spasm in my sphincter. Fortunately, I didn’t mark my laundry, as GI slang would have it, at a moment of sudden terror, though my sphincter ached for minutes afterward. I realized then that I was a coward.

At morning chow I mentioned the incident to several of my friends, but none of them had heard anything, since they were too exhausted to even dream. Ron Foster had been told by one of our ensigns, who’d seen the corpse, that the Japanese soldier was just an unarmed, emaciated kid. Pete Echeverry laughed. “Who gives a shit? The only fuckin’ good Jap’s a dead Jap.”

I was profoundly shocked, although I’d heard that remark many times. The Japanese were the enemy and we were conditioned to hate them, and as far as we were concerned it was either kill or be killed. I’d always had a reverence for Japanese culture, beginning with the first image of Japan I ever saw, a picture of Mount Fujiyama over the hearth of our cottage in Ireland, next to a holy picture of the Blessed Virgin Mary. The first of the many travel books I’d read was Lafcadio Hearn’s Glimpses of Unfamiliar Japan. And the first opera I’d ever heard was Madame Butterfly, which Jean Caputo played for me one afternoon in Brooklyn, translating the Italian into English. I particularly recalled the beginning of act 1, scene 5—“Ancora un passo” (“One step more”)—where Cio-Cio San can be heard guiding her friends to the top of the hill, jubilantly telling them, “Over land and sea, there floats the joyful breath of spring. I am the happiest girl in Japan, or rather in the world.” And then I heard the awful scream of the boy whose throat was cut in the jungle the previous night, the last sound he made on earth before descending into Yomi-no-kuni, the Land of Darkness, the Japanese Country of Dreams, where he joined the army of the dead who would live forever, eternally young.

I said nothing about the incident to Ed, because he was struggling to keep our truck from sliding over the precipice immediately to our right.

A couple of hours’ drive from Mongyu, we crossed from Burma into China at Wanting, where there was a Chinese army border post. We had to get out of our trucks to have our ID cards and our cargo checked, which seemed to be a ridiculous formality. I handed my ID to an arrogant Chinese army captain, who shouted at me in primitive English to hand over my .45, which he obviously intended to keep for himself. I told him in English to go to hell. I knew he understood me, because he drew his pistol and pointed it at my head. One of our ensigns came along in a jeep at that moment with a Chinese major, who shouted at the captain and made him put his gun away. The ensign told me and Ed to go back to our truck and get going. We did, and as we drove past the captain I had to force myself not to give him the arm gesture that I’d learned from my Italian friends in Brooklyn.

There seemed to be nothing to see, so I took out my copy of Ledo Lifeline to find out if I’d missed anything. I learned that this had been the site of the bloodiest battle of the Salween Valley campaign, which in six weeks during the previous year had squandered the lives of seventeen thousand Chinese and fifteen thousand Japanese soldiers, all of them buried in unmarked graves at the border post between Burma and China, soaking the earth in the blood of young men.

A precipitous turn on the old Burma Road

We were now on the old Burma Road, which, even to me, seemed very different from the Ledo-Stilwell Road. Once again I consulted Ledo Lifeline to learn about this ancient thoroughfare, which for millennia had been southwest China’s only link with the outer world. Its last phase had, beginning in 1920, been constructed by some 100,000 Chinese coolies, whose unmarked graves in their hundreds line the course of the roadway, unremembered.

The Burma Road section of the Stilwell Road has a history all its own. Cutting over the Himalaya Hump, it is the newest of many communications routes developed by the Chinese during the past 4,000 years. The Burma Road started from Kunming in 1920 along the general route of an old, little-used spice, tea, and caravan trail toward Burma. By late 1939 it was opened to Wanting, a Yunnan Province border village, to which place the government of Burma had built arteries to connect with their Irrawaddy River ports of Bhamo and Rangoon and the railhead of Lashio. The course of the road is not new, for Genghis Khan and Marco Polo in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, respectively, visited places along today’s route.

Our route for the rest of that day took us along the south bank of the Shweli River and then beside one of its tributaries, as the road brought us higher and higher and higher into the mountains of Yunnan, the southwesternmost province of China, which in earlier times had been part of Tibet, along with Sichuan Province to its north.

The road was pockmarked with shell holes and flanked by the burned-out and bullet-riddled wrecks of Japanese and Allied vehicles and artillery left over from the battle that had raged down this valley the previous winter. On either side, carved out of the treeless terrain, were myriads of foxholes, trenches, machine-gun emplacements, and bunkers. And above them on the terraced hillsides were the carefully tended graves of what the Chinese call “the summoned dead,” marked by funerary urns and incense pots. There was nothing to mark the graves of the young men who were killed in the fighting along this road of death, nothing except mounds of raw earth, covering Chinese and Japanese boys alike, all of them summoned by death before their time.

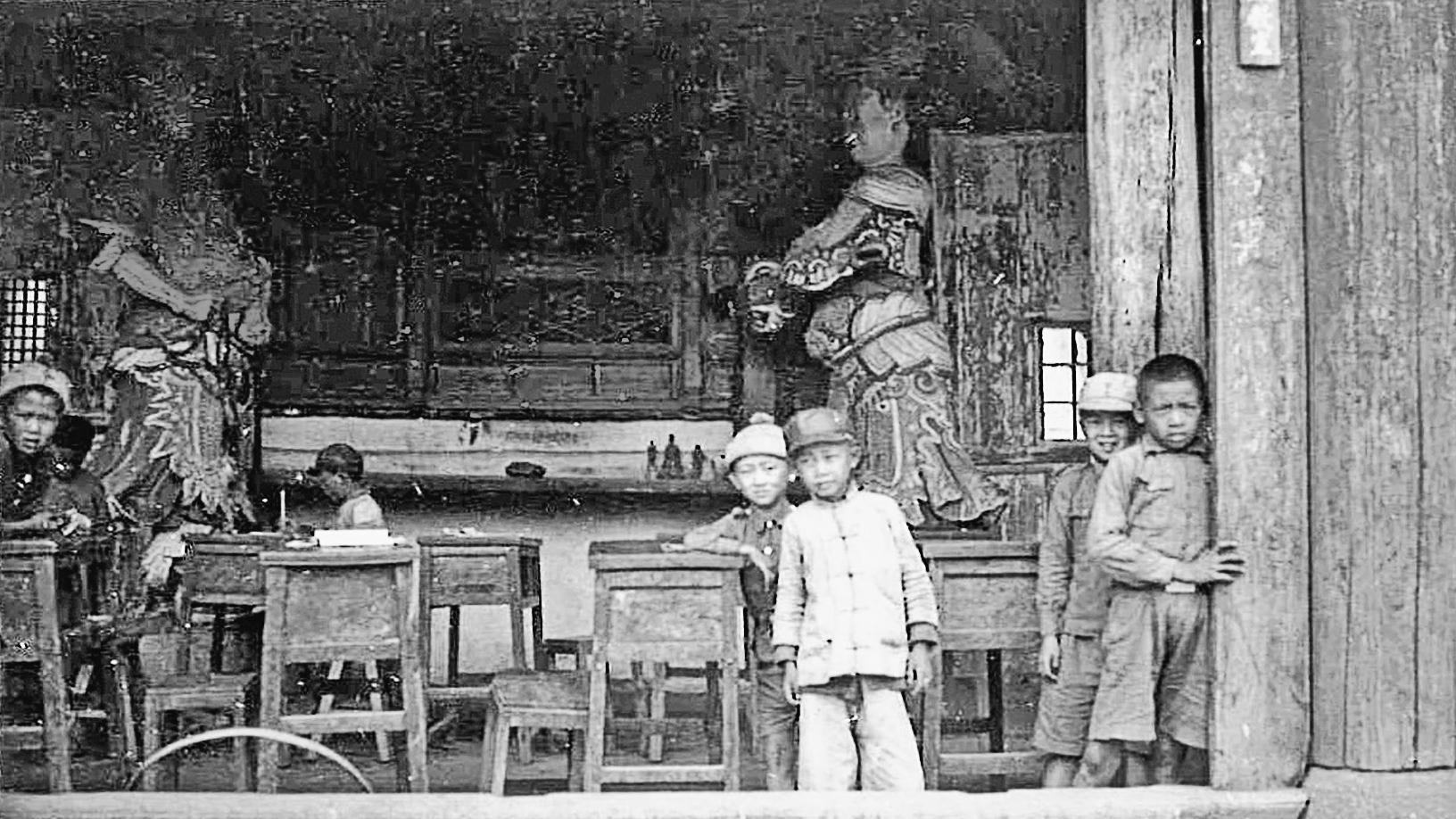

The villages through which we passed were all in ruins, but life seemed to be going on in them all the same, and in one of them I saw a class of young children being taught in a schoolroom whose walls and roof had been completely blown away. The children waved to us as we passed, while their teacher, an old man in traditional Mandarin dress with a long and wispy white beard, bowed gravely as he tried to get his students back to their lesson.

Chinese students in a partially destroyed school watching as our trucks went by

We spent the night at the bivouac station just outside Lungling, where I again consulted Ledo Lifeline, for it looked like a very interesting old Chinese town.

Lungling is a walled city on the edge of the Burma Road. The largest populated center on the road west of the Salween River, it served as the principal Jap supply outlet in the Salween country, and was captured by the Chinese in November, 1944, after a six-month battle. (Translation of Lungling: Lung = dragon, Ling = royal tomb.)

I spent an hour or so before evening mess wandering around the town, something I’d been unable to do elsewhere on our journey. I noticed that the people looked very different from the Chinese I’d seen in New York, much taller and with features somewhat resembling those of the Native American chiefs whose pictures I’d collected as a boy in chewing gum packages. I’d been told at Margherita that the people in Yunnan and Sichuan provinces were not Han Chinese, but from one or another of a score of minorities, most of them Tibetan in origin. As I recalled, the most interesting of these were the Bai, Mosuo, and Naxi, all of them matrilineal, where descent is traced through the female line rather than the male. Marriage was unknown in their communities, and women held all the power. I couldn’t wait until I told all of this to Peg, for she always said that the world would be a better place if women ruled.

I strolled through the market, where scores of itinerant peddlers—all of them women with big wicker baskets on their backs—were selling fruits and vegetables, which seemed to be in very short supply, for their baskets were virtually empty. I’d heard that famine was rampant in the surrounding countryside, and I presumed that these women were selling produce from their own little farms, though no one seemed to have any money to spend. Several of the women approached me, showing me the few pathetic things they had to sell. I was bewildered, not knowing what to do, for I would gladly have given them all the cash I had on me, which in any event was just the “funny money” we’d been given in Ledo at four hundred yen to the dollar.

Then I was confronted by a young woman with a basket of gnarled yams on her back. She said nothing, but held out two of the earth-encrusted yams for my inspection. I gave her all the money I had in the pockets of my fatigues, and she handed me the yams. We stood there for a moment, the two of us looking at each other across a cultural gulf as wide as the world itself. She was a bit taller than I was, crowned with an enormous nimbus of coarse black hair, her half-closed agate eyes gazing at me, a faint smile on her astonishingly beautiful face, mesmerizing me as if she were the goddess of the moon. Then, without a word, she turned and walked away, leaving me there with the yams, struck through the bones by her beauty. She was my wounded Amazon, sister of the one I’d seen at the Metropolitan Museum, and now she too was gone, except for the lingering memory of her serene beauty.

Nine miles farther along we passed Sungshan (Pine Mountain), the scene of yet another battle in the seeming endless war between China and Japan in this blood-drenched valley of death. Sungshan is a seven-thousand-foot promontory that had been known as the Japanese Gibraltar of the Salween. A Japanese garrison of two thousand had been exterminated here after three months of fighting on the steep slopes of the mountain. The stronghold finally fell on September 7, 1944, when Chinese engineers set off explosives that blew the top off the mountain and killed a large portion of the Japanese garrison. This was one of the most decisive battles of World War II for China, since it opened up the Burma Road for the Allies. But it was a Pyrrhic victory, taking the lives of some 7,600 Chinese soldiers and 3,000 Japanese, most of the defenders pulverized when their stronghold was blown up, reducing the garrison to the dust from which they emerged, their brief lives now a forgotten dream.

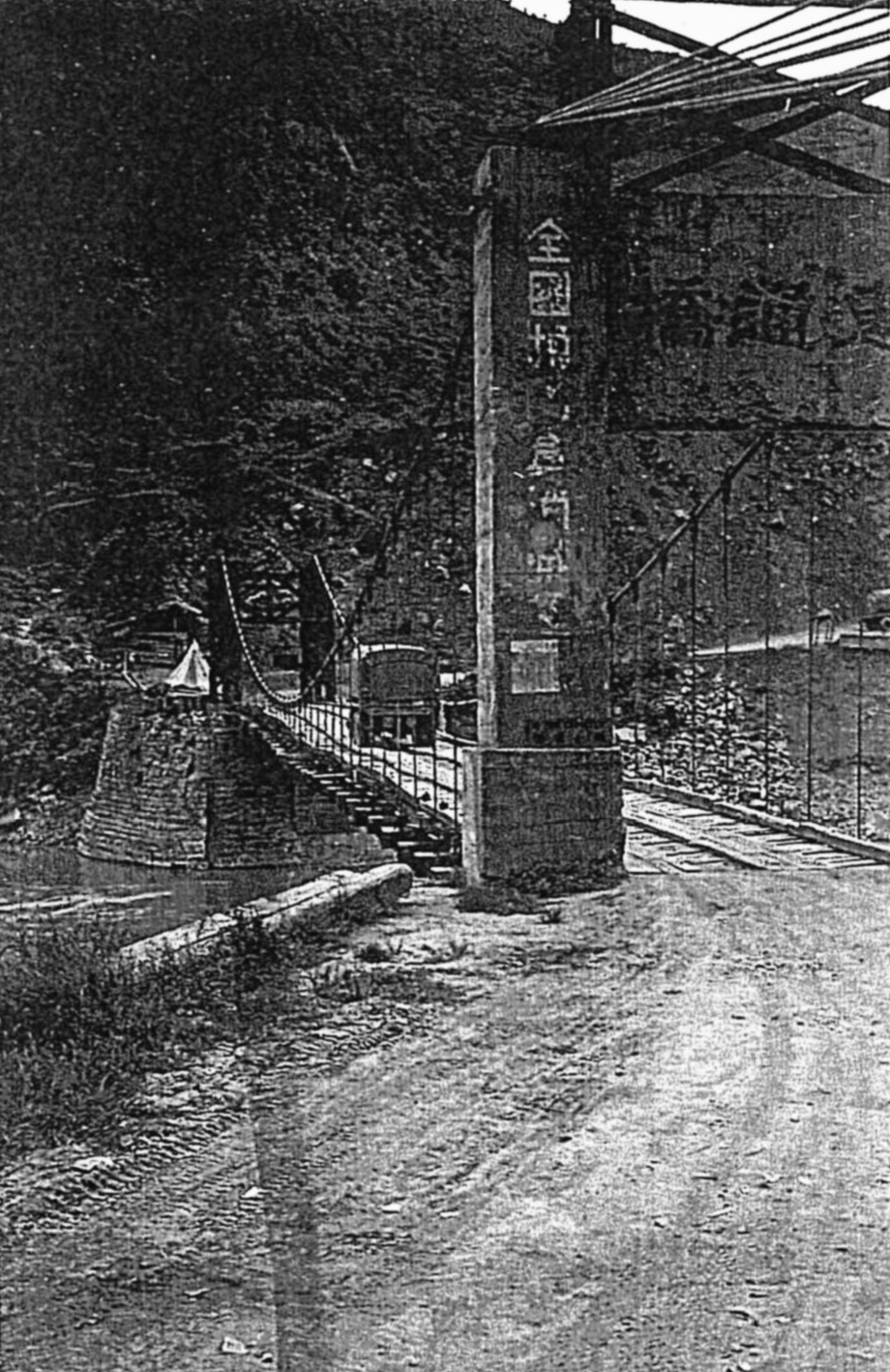

Looking down on the great gorge of the Salween, one of the Rivers of Paradise

At around noon the next day we came to the great gorge of the Salween, known in Chinese as Nu Jiang, the second of the Rivers of Paradise that we would cross.

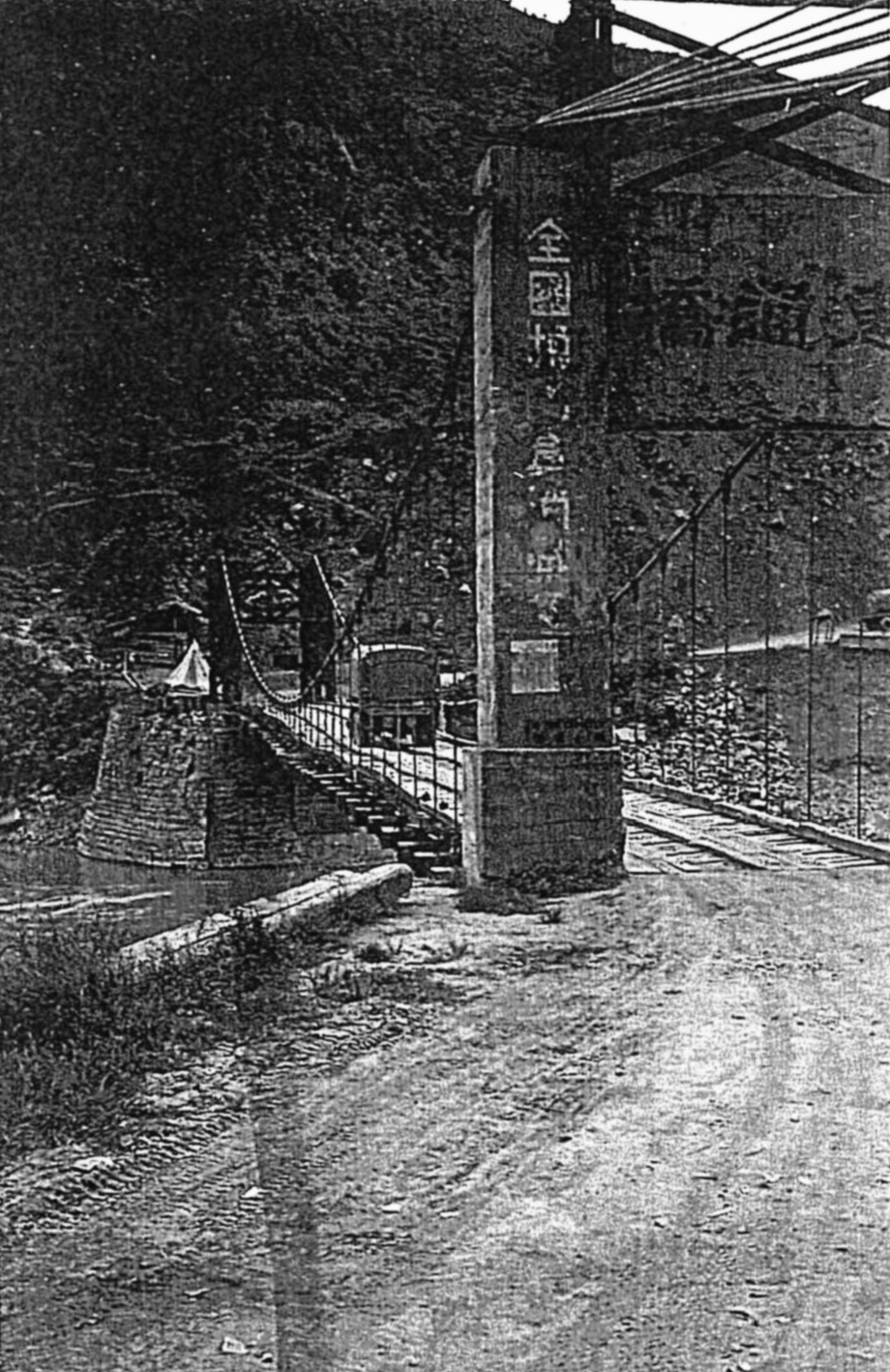

We would drive across the river on the Huitong Bridge, the lowest point on the Burma Road, at 2,960 feet above sea level. The original bridge was just a wooden catwalk on which one file of Chinese soldiers could cross at a time. This had been blown up in 1943 by American commandos to stop the Japanese from penetrating farther into Burma, effectively trapping them in the southern portion of the country. The young soldier I’d heard die a few nights ago would have been one of these unfortunate wretches.

It took us about an hour to wind our way down to the river through a succession of hairpin turns. Then, after we reached the approach to the bridge, we and the two convoys ahead of us had to wait while final repairs were made to the suspension bridge, which had been blown up by an American commando during the battle for Mongyu. (Thirty years later, at a party in Athens, I met the commando, a Greek American named Ernie Tzikagos, who told me that he almost lost his sight when the explosives he had placed on the bridge went off prematurely.)

While we waited to cross, the local children crowded around our convoy, trying to trade worthless copper coins for food. I gave one little boy a couple of my K rations and a can of fruit cocktail, and he handed me a large coin in return. I tried to give the coin back to him, but he wouldn’t take it, indicating with a wave of his hand that it was worth nothing to him. I scraped the coin clean and found that it was a Sun Yat-sen gold dollar and probably very valuable indeed. I thought to go in search of the boy to return his coin, but at that moment the convoy started up and I had to get back in our truck.

After crossing the bridge it took another hour to wind our way up around the succession of hairpin turns on the other side. When we reached the top I had an eagle’s view of the Salween, which, from my memory of the map in Ledo, I knew flowed all the way from Tibet through southwestern China and then Burma before it emptied into the Andaman Sea.

We spent that night and all the next day at the bivouac station at Paoshan, for most of the trucks were in need of repair. While Ed worked on our engine I took the opportunity to explore Paoshan, an old walled town on the southern branch of the Silk Road, which Marco Polo had passed through on his way to Kublai Khan’s summer capital at Xanadu.

The entrance to the bridge across the Salween River, August 1945

Much of the town was in ruins from the fighting that had taken place in opening up the Burma Road this past winter, and I was told by a GI at the base that there was a serious shortage of food because the Japanese had stripped the country bare and the war had disrupted the caravan trade on which this region had depended since the days of Marco Polo and before.

That evening I saw a long line of Chinese waiting outside the mess hall, and when I finished supper I learned that they were to be given what we had left on our trays. Instead of emptying our leftover food into garbage cans in the scullery, we scraped it into bowls and other containers held out by the emaciated Chinese waiting in the line, most of them old people and women with children, the young men having been taken off in Chiang Kai-shek’s army. I felt ashamed at having so little on my tray when I scraped it off into a tin can held out by a little girl, so I went through the chow line a second time and gave it all to an old woman, who took it without a word and limped away.

The mess sergeant noticed what I’d done and told me that he tried to feed everyone in the line with the food that was left over, but it was an impossible task, and he was afraid that when the U.S. Army left everyone in this region would starve to death.

I learned from Ledo Lifeline that the population of Paoshan in 1942 had been 400,000, but now it was less than half that. On May 4, 1942, the Japanese army had shelled the city heavily, killing 10,000 townspeople. Some of the shells contained germs causing cholera and bubonic plague. More than 60,000 people in the Paoshan area died of cholera in the weeks after the bombing, and thousands more succumbed to bubonic plague, which was still endemic in the region.

Looking down on the Salween River and its bridge after the crossing

The next morning we started off for Yungpin, a distance of a hundred miles, which we were told would be the most difficult stage of our journey in China, because parts of the road had been washed away by the monsoon and had not yet been fully repaired. About two-thirds of the way there we crossed a pontoon bridge over the Mekong River, which flows down from Tibet through Yunnan Province in China and then through or between Burma, Laos, Thailand, Cambodia, and Vietnam, before emptying into the South China Sea, passing Mandalay on the way.

After we crossed the Mekong, the third of the four Rivers of Paradise, the monsoon set in again and we were struck by a torrential rainstorm, which turned the road into a river of mud and washed even more of it away. By sunset there was no sign of Yungpin, though Commander Boots sent a messenger back from the head of the convoy to inform us that we didn’t have far to go. The convoy was now strung out so far that we couldn’t see the trucks at either end. With the failing light and torrent of rain our visibility was very limited. Finally word came from the commander that Yungpin was in sight. But by the time we reached the side road that led into the camp we had great difficulty finding our way through the canopy of jungle that surrounded and arched over us.

One of our ensigns was there in a jeep, waving a flashlight to draw our attention. He handed me the light and told me to stand there by the side road to direct the trucks behind us into the camp. I did as I was ordered and Ed drove off behind the ensign into the camp, though after they left I could barely see where the side road led off from the Burma Road.

The trucks behind us came along every minute or so at first, and as they approached I waved my flashlight to direct them into the camp. Then the interval between trucks became longer and longer, as I waited in mud up to my ankles, and although I was wearing my poncho I was as drenched as if I’d been swimming in my clothes. One of the trucks got stuck in the mud as it turned into the side road, though the driver did manage to maneuver it so it wasn’t blocking the way. The driver and his buddy decided to abandon the truck for the time being and walk on into the camp, locking the cab because they had stowed their weapons there.

I was already so drenched that it hardly mattered, but I thought that I’d take cover under the truck, where I would at least be out of the rain. I crawled under the tailgate and wrapped myself up in my poncho, emerging whenever I heard the roar of an approaching truck so I could wave my flashlight to direct the driver onto the camp road.

The ensign who had given me the flashlight eventually returned in his jeep and told me that there were still trucks stuck out on the road. An emergency vehicle would try to get them started, but he thought that some of them might be stuck out there for the night, though they would try to bring the men into the camp. He told me to stay at my post until told otherwise, and he would try to find someone to relieve me so I could get some chow before the mess hall closed.

About an hour later a truck appeared, and I directed it into the camp road. The driver and his buddy told me they didn’t think any more trucks would make it that night, for even our emergency vehicles were now stuck in the mud, and they offered to give me a lift into the camp. But I told them that I’d been ordered to stay at my post until relieved, so I crawled back under the truck, where I wrapped myself in my poncho and resumed my vigil.

I’m sure no other trucks arrived during the night, for although I dozed off I would have been awakened by the roar of their engines. When I did wake up I could see from under the truck that the sun was shining, though the road was still a morass of liquid mud. Then I became aware that someone standing behind the truck was nudging me with his boot, and I crawled out to find a tall black American soldier standing over me, his stripes and insignia identifying him as a top sergeant in the Army engineers. He had a big smile on his face as he looked down and helped me to my feet.

“Wake up, soldier,” he said, “the fucking war’s over!”

He told me that the U.S. Army news broadcast on the previous night had announced that the Japanese government had surrendered unconditionally earlier that day, August 15, 1945. We’d been out of touch with the rest of the world since we left Ledo, and once again I’d lost track of the days—this time on dry land rather than at sea—so I knew nothing of the events that had led up to this astounding news. The war had become a way of life, always in the background of my thoughts since my early teens. And now it was over! I felt as if the curtain had been brought down before the drama ended.

On the way into the camp, the sergeant told me that on August 6 the United States had dropped a powerful new weapon called an atom bomb on the Japanese city of Hiroshima, obliterating its center and killing a large part of its populace. Three days later, he said, an even more powerful atom bomb had destroyed Nagasaki and incinerated everyone in the city center. President Truman had demanded that the Japanese surrender unconditionally, and they had announced their submission on August 15, with the details of the formal end of hostilities to be worked out in the coming days.

I was stunned, for nothing in my past experience had prepared me for this incredible news, which seemed to mean that the war had suddenly come to an end, just as my great adventure was beginning. But by now the death and destruction and near starvation I’d seen during the past weeks, along with the unrelieved misery of our way of life, day and night, had eroded the notion that my journey was an adventure. I was deeply confused.

I remembered all of us sitting in the living room on Sunday, December 7, 1941, when we heard the news that Pearl Harbor had been bombed, on what Present Roosevelt called “a date which will live in infamy.” I had followed the progress of the U.S. forces in Europe, North Africa, the Pacific, and the Far East, hoping that I could enlist in the Navy as soon as possible, never dreaming that I would end up in China, hundreds of miles from the sea, thinking the war would never end. And now it had ended, abruptly. I didn’t know what to think.

I thought again of Cio-Cio San jubilantly telling her friend, “I am the happiest girl in Japan, or rather in the world.” And then I heard the death cry of the boy whose throat was cut at Mongyu. It was all over, except for the awful memories.

The sergeant said that the whole base was whooping it up, and he invited me to join him and his pals in their barracks. They’d collected enough booze to get them through the war, and they sure weren’t going to leave any behind. I thanked him for the invite, but I said that I had to check in with my outfit and have some chow, since I hadn’t eaten anything since the morning of the previous day.

He pointed out the mess hall, and as I started in that direction I passed a barracks where some white GIs were having a party. One of them saw me and said, “Hey, take a look at that fucking sad sack!,” drawing a big laugh at my expense, for I must have looked like a drowned rat that had been dragged through the mud.

I made my way to the mess hall, where I joined Ed and the rest of our outfit for breakfast, the first real food we’d eaten since leaving Ledo. We mustered after we left the mess, and Commander Boots told us that we would be staying in Yungpin for the rest of the day and our convoy would resume its journey the next morning. Although the government of Japan had agreed to surrender, the war was still going on, he said. The Japanese troops in the field were still a threat, and although their army had been defeated in the battle for Mongyu, there were thousands of them in the highland jungles around us who had not given up. We’d have to be on our guard at night because they were desperate for food, as I knew from my experience at Mongyu.

Ed led me to our barracks, where I showered off the mud that had caked all over my body. I was also covered with leeches from sleeping on the ground, and I had to peel them off one by one, each of them leaving a bloody welt on my skin. My “rotten crotch” was quite painful in the hot shower, the first one I’d had since we left Calcutta. I washed my only set of skivvies in the shower, for I’d ditched the rest of my underwear and my only pair of socks because they were in such foul condition. I sat outside, naked, waiting for my skivvies to dry, but there was no sun and I had to wear them still wet, putting on my mud-encrusted combat boots with exquisite care so as not to further aggravate the painful jungle rot on my ankles. Then the sun emerged from within the clouds long enough to buoy up my spirits. I was happy to be alive.

We joined a big party that was going on in the base headquarters, where everyone I spoke to, most of them black, told me that they had been in the CBI for three years or more without leave, and all they could talk about was going home. Everyone got very drunk, including the pet monkey that had become the base mascot—the second drunk monkey I’d seen in recent days. I wondered how these poor creatures would adjust to life in the jungle when the GIs left. I also wondered how the GIs themselves would adjust to normal life after years of war, death, and destruction. Most of them had left behind wives and children, as well as grandparents who had died since they left, and infant sons and daughters they knew only from the photographs they showed me.

The guys in my own outfit were much younger, virtually all of them in their late teens or early twenties. A few of them were married, and most of the rest were engaged or going steady. Pete Echeverry had been run out of his hometown by the sheriff, “just cause ah was shackin’ up with his wife. Gotta find another place to live when ah go home!”

Ed Hill was a very private person, and although we’d endured a month together in our truck I knew virtually nothing about him, other than that he was a very nice guy. Now, after he’d downed a few swigs of rye whiskey, he loosened up a bit and showed me a photo of a quite beautiful girl with long auburn hair. He said nothing, and then put the picture back in his wallet.

I didn’t have a wallet, nor did I have a photograph of anyone, not even Peg. But all of this had stirred the well of memory, as the Irish say, bringing to its surface a succession of almost forgotten images, some of them of them happy, others painful.

I was back in Brooklyn, in the playground at PS 96, around the corner from Fourteen Holy Martyrs. I’d been playing basketball with my friends, and I was taking a break, sitting with my back up against the chain-link fence. I’d just gotten a crew cut at Louie’s barbershop. He charged me only a dime, which was all the money I had, and my head felt cold in the spring breeze. Marie Nolan was standing behind me, watching the game. She’d watched me play touch football and stickball and roller skate hockey. She never said anything, but she smiled whenever I gave her a glance. She was only fifteen, two years younger than I was. She was small even for her age, but very pretty, with a big mop of curly blond hair, and she always wore a black corduroy jacket that had been handed down from her older brother. She put her hand through a gap in the fence and ran her fingers through my blond stubble. Ed Kettle saw this and laughed. “How could anyone love a head like that?” I blushed, and Marie did too. Then I said to her, “Would you go to the movies with me on Friday night?” She smiled and nodded her head, and I said, “See you at seven.” She smiled again.

During the week I earned a couple of dollars scavenging with Jimmy Anderson, and I borrowed John Mione’s sport coat. Marie’s father worked with my father in the Evergreens Cemetery, so he’d given permission for her to go out with me. It was her first date, and mine too, not counting Mary McCabe.

It was a beautiful spring evening and the few trees in Brooklyn were beginning to green, perfuming the night air. I took Marie by the hand as we crossed Bushwick Avenue even though there wasn’t a car in sight. We walked to the RKO Gates, on Broadway and Gates Avenue. The film was The White Cliffs of Dover, starring Irene Dunne and Alan Marshal, with Elizabeth Taylor in a supporting role. There was a long line for tickets, but one of my pals worked there and let us jump the queue. The minimum age for evening admission was eighteen, and minors were allowed in only with an adult. But I was tall for my age and passed, even with my crew cut, and I pretended that Marie was my kid sister, though we didn’t look at all alike. The woman selling the tickets looked me over very suspiciously, but she finally let us through. Marie and I tried to make ourselves invisible while everyone milled around in the lobby, and then we did the same when we went in to see the film, finding two seats in the middle of the theater where we wouldn’t be noticed. The newsreel had already started, and we saw British Lancaster bombers blowing Nuremburg to bits. Then, after a Tom and Jerry cartoon, The White Cliffs of Dover began.

It was a romantic tearjerker, and many of the women in the audience were dabbing at their eyes. I heard Marie sniffling too, so I put my arm around her and drew her close. She rested her head on my shoulder and I held her tightly by the hand. I was suffused with happiness, and I paid no attention to what was happening on the screen, for Marie and I were engaged in our own romance, and I wondered if she felt the same way that I did. She looked up at me and smiled.

I didn’t see Marie again until late September, at the end of my first home leave in the Navy. My leave was coming to an end, and I was walking back along Wilson Avenue toward the subway station. As I passed Decatur Street I saw Marie standing there wearing her brother’s black corduroy jacket, an early-autumn breeze ruffling her mop of blond hair, her eyes what the Irish call “a most unholy blue.” She’d heard I was home, she said, and I told her that I’d spent the whole week with my family, which was true, and neither of our families had a telephone—nor did anyone else we knew—so I had never gotten in touch with her. But there was no need to, knowing each other as we did. So I just took her by the hand and we walked together to the Wilson Avenue subway and said goodbye.

And that was the last I ever saw of Marie, for when I came home again in late spring, just before going overseas, I was told that the Nolans had moved to Long Island, and no one knew their address. Marie slowly sank into the well of memory, the deepest of wells, only coming to the surface here in the black night of southwest China.

I was back in the barracks at Yungpin. The party was over, for everyone was dead drunk or sound asleep or both. I left the barracks for a few minutes to catch some fresh air, but it was damp and humid and smelled of rotting vegetation. The only sounds were the occasional howls of jackals and the rustling of the trees and brush in the surrounding jungle when a slight breeze blew up. Then I heard the Japanese boy screaming and I fled inside, stuffing the pillow over my head to shut out the awful sound. The screaming stopped and I just lay on my cot trembling before I fell asleep and escaped my memories for a few hours.

We started off at the crack of dawn the next day, for we’d been told that there was a very long and dangerous stretch ahead of us. We would drive 121 miles to Yunnanyi, which would take us over the Quingshuillang Mountains, whose highest peaks rose to nearly nine thousand feet. By noon we were high in the mountains, snaking from one vertiginous ridge to another, with the edges of the road partially washed away by the monsoon in many places. We were making our way cautiously along the side of a steep canyon when the truck in front of us stopped so suddenly that we almost ran into it. I jumped out to see what had happened, and I saw that the second truck in front of us had skidded off the road and rolled down several hundred feet into the canyon, where it had tumbled onto its side, wheels still spinning.

I climbed down to the wreck with about a dozen others and we found the driver unconscious behind the wheel, while the other man in the truck, who’d been thrown clear, was conscious, bleeding profusely from a gash in his forehead. I recognized the driver as Coxswain John Jacob Esau, and the other man as Ensign Dawson.

We were soon joined by others from the convoy, including the two pharmacist’s mates, one of whom looked after Esau and the other Dawson. They strapped Esau in a stretcher tied to the cable of our emergency vehicle, which then winched it up to the road as we lifted it along the way. Dawson was brought up the same way, and then when they were both laid out in an ambulance it set off toward Yunnanyi, where there was a small field hospital.

When we arrived in Yunnanyi, we were told that Esau and Dawson had been sent off to Kunming in a regular ambulance with a doctor and a nurse in attendance. Dawson was stable but Esau had a fractured pelvis along with internal injuries and was in critical condition, and was being taken to the U.S. Army base hospital in Kunming.

The next day we started out for Tsuyung, the penultimate stage of our journey, a drive of eighty-three miles that brought us up onto the mile-high Yunnan Plateau, the easternmost extension of the great Tibetan Plateau. Tsuyung, at the southern tip of Lake Erhai, is the “New City” of the beautiful medieval town of Dali, which I’d read about in National Geographic, and which I could now see on the western shore of the lake directly under the majestic Cangshan Mountains, their peaks rising to nearly thirteen thousand feet. I figured we were only some two hundred miles from the snow-plumed peaks at the eastern tip of Tibet, which I’d seen from Assam and could now see again from China since our route had taken us halfway around the eastern approaches of the Roof of the World.

Here again, as in the other towns we’d passed along the Burma Road, the locals looked very different from the Chinese I knew in New York, and I was sure that most of them were from the Bai, Mosuo, and Naxi tribes. I could see a range of enormous snow-shrouded peaks to the north, which I recognized as Jade Dragon Snow Mountain, to the north of Lijiang, the regional capital, inhabited almost entirely by Naxi. Farther north, around Lake Lugu on the great bend of the Yangtze, was the home of the Mosuo, who called their domain the Kingdom of Women.

I wandered around the marketplace, which seemed to be run entirely by big strapping women with moonlike faces, regal in their bearing, though lacking the surpassing beauty of my Lost Amazon. I spoke to them in my smattering of Chinese, but they didn’t seem to understand a word I was saying. I managed to buy a couple of eggs from one of them, and that evening I boiled them in my helmet over a fire that Ed had lit outside our pup tent.

At Tsuyung the Burma Road was joined by two other roads, one from the north and the other from the south. The road from the north was the old caravan trail from Tibet, while the other was the continuation of this route down to southern Yunnan and Burma. We were told that the Chinese divisions that had been fighting in southern Burma were now being evacuated along this route before turning onto the Burma Road and heading for Kunming, marching day and night without stopping, for they had no food. Once they reached Kunming, they would be expected to march in a parade to celebrate Chiang Kai-shek’s “glorious” victory over Japan.

We set out the next morning on the last stage of our journey to Kunming, a distance of 120 miles. We found ourselves driving between two seemingly endless columns of Chinese soldiers, their rifles slung over their shoulders, who hardly glanced at us as we passed. They wore only sandals, and their tattered uniforms hung like shrouds from their emaciated bodies as they staggered along, some of them barely able to walk. Once we had to swerve to avoid a dead Chinese peasant lying faceup in the road, his body swollen and covered with flies, not even noticed by the soldiers as they marched by impassively.

It was dark by the time we reached Kunming, and as we approached the city we were met by a U.S. Army jeep that led our convoy to where we would camp for the night. Our campsite was on the edge of the airfield on the southern side of Kunming, where we set up our tents just beyond the end of the runway.

I was so exhausted that I got into my sleeping bag soon after I finished my K rations, but it took me a long time to fall asleep because of the succession of airplanes coming in to land just over our heads. The planes were still landing when I awoke at dawn, most of them C-47 transport planes that had been carrying troops and supplies over the Hump from India to China for the past three years.

Every now and then a fighter plane landed as well and taxied to our end of the runway. I went over to look at one of them and saw that the nose of its fuselage was painted to resemble a shark’s head. I recognized this as the symbol of the Flying Tigers, the 1st American Volunteer Group, which was founded in 1941 by General Claire Chennault, who commanded the Chinese air force and then later became head of the U.S. air forces in China.

I talked to the pilot after he emerged from the plane. He told me that he had just made his last flight, because now that the Japanese had surrendered he figured he and his comrades would soon be going home, although no official orders had yet been received. Like the other Flying Tigers, he had been flying combat missions for more than four years. He was sick of war and just wanted to go home and live a normal life, though he could hardly remember what normal life was like.

Commander Boots spoke to us when we mustered after morning chow at the mess hall. He’d just received word that the Japanese were going to sign a formal document of surrender aboard the battleship USS Missouri in Tokyo Bay on September 2, 1945, two days from then, and we cheered, though we’d seen only the tail end of the war. It had been enough, I thought, thinking of the road to Mongyu and the boy screaming in the jungle.

The commander said that we’d drive to a parking area in Kunming, and from there we would be taken to the main SACO base in Kunming—Camp Hank Gibbins—where we would receive orders for our individual assignments. Some of us would go on with the convoy to Chengdu in Sichuan Province, where SACO had its main headquarters, but each truck would now have only one driver, for since hostilities had ended it meant that plans would change for half of us. We would not be flown over the Hump to Calcutta to be shipped back to the United States, but otherwise, he said, the details were still uncertain.

Kunming is more than six thousand feet above sea level, rimmed by mountains on three sides, giving way to terraced hills with rice paddies whose pools were glistening in the sunlight when I looked at them early in the morning after our arrival. The high altitude made it deliciously cool, and we had to break out our foul-weather jackets before the convoy started up. We were told that we were headed for a godown, or depot, on the western outskirts of Kunming, where we would park our trucks and await further orders.

We mustered again after we parked our trucks in the godown, which looked like a caravansery I’d seen in a travelogue on Central Asia. It consisted of wooden structures with pagoda roofs surrounding a huge square crowded with oxcarts and coolies carrying enormous loads suspended from bamboo poles. Commander Boots said that most of our outfit would be put up at Camp Hank Gibbins, but due to lack of space a few of us would be temporarily housed in the main camp of the Chinese 1st Army Group, where General Tai Li’s Loyal and Patriotic Army was based. One of the ensigns read out the list, and I found that I was one of five assigned to the Chinese army base. My group reported to a lieutenant in the Chinese army, who in broken English told us to get into the back of a truck, and in a few minutes we drove off from the godown, waving goodbye to the rest of our outfit.

The Chinese army base was in the hills above Kunming, and on the approach road we passed between the same columns of ragged and emaciated soldiers I’d seen on the previous day. When we reached the base we were taken to a separate enclosure for the LPA, where the Chinese soldiers seemed healthier and better clothed than those of the regular Kuomintang army—all of them, so far as I could see, wearing American uniforms and combat boots just like our own. They were housed in tents with screens on the sides to keep out the mosquitoes that had plagued us along the Burma Road, while the soldiers in the regular army slept in overcrowded barracks.

The lieutenant assigned each of us to a tent together with a Chinese soldier who would be our interpreter while we were in the camp. My interpreter was a private in the LPA who introduced himself in very basic English as Ching Ging Too, which he wrote out for me in both English and Chinese, after which he led me to our tent, whose only furnishings were two U.S. Army–issue folding cots. He was a slender young man, about my age, taller and darker than the regular Chinese soldiers, and from his moonlike visage I figured that he was from the Naxi or one of the other tribes in the Tibetan borderlands.

Ching offered to take me to the mess hall, “but the food was pretty bad,” he said. Giving me a quick lesson in Chinese, he said that ding how meant “good” and boo how was “bad.” Then when I said “Ding how,” he laughed and replied, “Don’t ding how me, you boo how bastard,” a phrase that his American comrades in SACO had taught him.

I suggested to Ching that we use what was left of my “funny money” to buy some food and rice wine—we could have our own party to celebrate the end of the war on September 2, two days hence. He thought that was a great idea, so he got permission for us to leave the base. We bought our food and half a dozen bottles of wine in the local village. He purchased enough food to last us for at least three days, including rice cakes, Azabi beans, and “crossing the bridge” noodles, a Kunming specialty, along with a dozen slabs of baba bread.

I learned that Ching was twenty years old, a year older than I was, and that he was from a small village southwest of Kunming, under Jade Dragon Snow Mountain, where his family had a tiny farm. He had served in the LPA for two years and had fought against the Japanese in several hit-and-run guerrilla raids led by Americans in SACO.

After we ate, Ching took me for a walk around the camp and pointed out a large complex of Quonset huts in the valley below, which he identified as the Associated Universities of Southwest China. The students and faculty were from all over China, he said, and they had been moved here during the war to keep them out of the hands of the Japanese. (Twelve years later, at Princeton University, I met two Chinese physicists, Tsung-Dao Lee and Chen Ning Yang, who had just won the Nobel Prize, and I learned that both of them had graduated from the Associated Universities of Southwest China, and that they were there during my brief stay in Kunming.)

Ching said that he had hopes of going to this university when he was discharged from the army, because he dreamed of being a science teacher. But it might be a long time before he got out of the army, he said with a sigh. He explained that Tai Li would undoubtedly keep the LPA under arms even though the Japanese had now surrendered, for another war was about to begin between Chiang Kai-shek’s Kuomintang army and the Communist People’s Liberation Army (PLA) of Mao Tse-tung. He told me that Mao had spies and organizers right here in this camp, and he himself had been approached by them. (Forty years later, at Harvard, I met a prominent Chinese editor who was in the United States on a Newman Fellowship, and he told me that he had been at the Chinese army base in Kunming while I was there, spying and recruiting for Mao’s PLA.)

Ching said there was going to be a military review at the base on September 2 to mark the official Japanese surrender, and he expected that all of Kunming would join in the celebration. He suspected that things might get out of hand in town, for there would be thousands of armed soldiers on the loose and many of them would be drunk and disorderly. They had been at war since 1937, when Ching was twelve years old, so he hardly remembered what China was like in times of peace, before the killing began.

The review was held early in the afternoon of September 2 on the huge drill field of the base. Ching identified the various contingents of the LPA and of the regular Chinese nationalist army as they passed in review, led by their generals and other officers. I was hoping to catch a glimpse of General Tai Li, the commander in chief of the LPA, but Ching said that he was probably still in Chongqing along with SACO’s American commander, Admiral Milton Miles.

Toward the end of the review, Ching pointed out the women’s battalion of the LPA, and he said that many of them were from the Bai, Miao, Mosuo, and Naxi minorities in Yunnan and Sichuan provinces, some of whom I’d seen in Dali. The sight of them reminded me again of the Amazon I’d seen at the Metropolitan Museum, but whereas she had been forlorn and defeated these Chinese Amazons were triumphantly celebrating China’s victory over Japan.

After the review, which lasted all afternoon, Ching and I went back to our tent and had supper, which we washed down with the first of the half-dozen bottles of rice wine we’d bought in the village. After the first bottle of wine, Ching began to sing what he said was an old Naxi folk song, which I found quite beautiful, though I didn’t understand a word of it. When he finished he said that it was called “Waves Washing the Sand.” He translated a few lines for me, which were to the effect that time passes like the waves of the sea lapping upon the shore, and memory is the faint pattern left by the ripples on the sand, soon to be washed away.

Our party was suddenly interrupted by a burst of fireworks, and we rushed out of the tent to look at it. We could see that there were two separate fireworks displays, one on the drill field of our camp and the other in the city below, in what Ching said was the main square of Kunming. The displays lasted for about fifteen minutes, and when they ended we went back into our tent to continue our party.

Soon afterward the party was interrupted again by what we thought at first was a resumption of the fireworks, which surprised us. When we went out to see what was going on we quickly realized that it was not fireworks we were hearing, but gunfire, including bursts of machine-gun fire, sounding as if there was a battle being fought between the two sides of the camp. We went back inside the tent and took cover, for we could hear bullets whizzing over our heads. I crawled into my sleeping bag and lay down under my cot for whatever extra protection that might furnish, having brought a bottle of rice wine with me. Ching did the same, and as we sipped our wine we chatted during intervals in the gunfire until we dozed off.

When I awoke the next morning Ching was already up, and he showed me about a dozen bullet holes in the sides of our tent, some of them very close to where we had been sitting. He said that what we had heard was a fixed battle between two armies in the camp, one commanded by General Lung Han, the Yunnan warlord, who had apparently defected to Mao Tse-tung, and another led by General Tu Yu-ming, one of Chiang Kai-shek’s right-hand men. It seems, from what Ching had heard, that Chiang Kai-shek had ordered Tu Yu-ming to take control of Kunming before the Americans pulled out, and though the battle was a standoff Ching was sure that the two armies would resume fighting before long. He was right, and I later learned that the battle I’d heard was part of the prelude to the Chinese civil war.

(Julia Child, in her autobiography, wrote that she was giving a big dinner party that evening in Kunming, where she was with the staff of Lord Mountbatten, the commanding general of the Allied forces in the China-Burma-India theater. All hell seemed to have broken loose in the Chinese army base, and when shrapnel began falling in the city she was forced to call off the dinner.)

Later that morning a U.S. Army truck came with orders to take the five of us from SACO down to Camp Hank Gibbins, for it was obviously too dangerous for us to remain on the Chinese base. So Ching and I said goodbye, promising to try to get in touch with each other after we returned to our homes—but we knew that there was little likelihood that we’d ever see each other again.

Camp Hank Gibbins was in the village of Hai-ling, ten miles south of Kunming. When we arrived in the camp there were still no bunks available for the five of us, so we laid out our sleeping bags in one of the storage sheds. We mustered with the rest of our unit after chow the next morning. Commander Boots said that we could all spend the rest of the day on liberty in Kunming, and that trucks would be available to take us into town and back to the camp in the evening.

Ed and I spent the day wandering around Kunming, surrounded by curious crowds staring at us wherever we went. At one point we were walking along the main avenue when a motorcade of American jeeps and staff cars appeared, slowly making its way through the mass of humanity that blocked the way. The lead jeep stopped next to us for a moment, and I asked the GI who was driving it what was up. He said that the civilians in the staff cars were members of an American congressional delegation, who had stopped off in Kunming before going on to see Chiang Kai-shek in Chongqing.

As the motorcade drove by, the congressmen all turned to look at me and Ed, for we had on our Navy uniforms, surrounded by a sea of Chinese wearing the padded jackets that everyone in China wore in those days. I thought that the congressmen must have wondered what two American sailors were doing in this remote part of the world, hundreds of miles from the nearest ocean.

Three days later we learned that John Jacob Esau had died of his injuries in the U.S. Army hospital in Kunming. The following day we buried him on a hillside above Kunming, where a small military cemetery had been laid out for the American servicemen who had perished in Yunnan during the war. An Army chaplain conducted a brief service, then a bugler sounded Taps while a guard of honor fired a volley as his coffin was lowered into the grave. Commander Boots took the American flag that had covered the grave, and he said that he would make sure that it was delivered to Esau’s parents. I wondered how his parents would feel when they learned that their son had passed away four days after the official end of hostilities, one of the last American fatalities of World War II, buried half a world away from his home. I hardly knew him, but he seemed like a very nice guy. In his brief tribute to John Jacob Esau, Commander Boots said that he had just turned twenty-one. He, like so many others, would never grow old, deprived of life just as he had come of age.

The next day I moved into the barracks, as there were now vacancies made by those who had been flown back to Calcutta. Meanwhile, new arrivals were coming in from China and even beyond, including some SACO commandos who had been training Mongol cavalry for the LPA in the Gobi Desert and others who had made contact with Mao and his forces. Those who had been out in the field told me that a civil war in China was imminent, which I’d seen for myself just a few days before, and they were all sure that Mao would prevail over Chiang Kai-shek, for he had far greater support among the Chinese people. I guessed, however, that the congressional delegation I’d seen a couple of days before would be assuring the generalissimo that the United States was solidly behind him.

Two days later a notice was posted on the bulletin board informing us of our next assignments. I learned that I was one of a group of thirty who would be flown back to Calcutta on September 15, while all the others in the convoy, including Ed Hill, would drive the trucks on to Chengdu, starting the following day. There would be only one driver in each truck, which was why I’d been left off the list of those going on with the convoy, for Commander Boots knew I couldn’t drive. Nevertheless, I was very disappointed, for scuttlebutt had it that at Chengdu the trucks would be put on barges that would take them and their drivers down the Yangtze to Shanghai, where they would be shipped back to the States. The rumor turned out to be true, as I learned several months later when I received a postcard that my pal Ron Fuller sent to me from Shanghai.

I spent the intervening days wandering around Kunming with Ed, surrounded by crowds everywhere we went. We saw the two Tang Dynasty pagodas, the Yuantong Temple, and the Nancheng Mosque. The mosque surprised me, for I hadn’t known that there were Muslims in that part of China.

That evening I spoke to an ensign at Camp Hank Gibbins who had studied Chinese history, and he told me that the Muslims in Yunnan were Mongols, descendants of the warriors that Kublai Khan had led in his march of conquest. Marco Polo mentioned these Muslims when he passed through the city later in the thirteenth century, when it was known as Yachi, later changed to Yunnanfu, and later still to Kunming.

Around noon on September 15, I said goodbye to Ed and my other friends who were continuing with the convoy to Chengdu. We’d been through a lot together and I would miss them, particularly Ed. Although we still weren’t that close as friends, we’d been side by side constantly for two months, day and night. When I shook his hand, I knew somehow I’d never see him again.

The thirty of us who were leaving were taken in trucks to the airfield. We boarded a C-47 cargo plane, one of the famous gooney birds that had carried troops and supplies over the eastern extension of the Himalayas between China, Burma, and India. Hundreds of these planes had crashed or been shot down during the previous three years, but at least now we wouldn’t have to worry about encountering Japanese fighter planes. Still, I was very nervous when I boarded the C-47, for I’d never flown before, though I’d been fascinated by airplanes ever since I first heard of Charles Lindbergh’s solo flight across the Atlantic in the Spirit of St. Louis.

We sat on canvas bucket seats facing one another across the central aisle. The flight engineer, a young lieutenant, told us that the ride might be very rough, which was why they called flying the Hump “Operation Vomit.” He said we should put on our foul-weather jackets, because we’d be flying at a high altitude and it would be very cold; because the cabin wasn’t pressurized, we also might have trouble breathing.

The lieutenant said that we would be taking off as soon as the last passengers arrived, which puzzled me, since there were no seats left. A few minutes later a black GI from the Transportation Corps came up the ramp leading a line of five mules, which he tethered to a rope along the center aisle of the aircraft. He laughed when he saw the expressions on our faces, and said the U.S. Army was abandoning its trucks and jeeps as it pulled out of China, but not its mules, which had carried supplies and weapons all through the war and now were being taken back to the States to spend their remaining days in honorable retirement.

As soon as the mules were tethered we took off, and after a few minutes of sheer terror I relaxed and tried to enjoy the scenery, craning my neck to look out the window behind me, since the view through the window across the aisle was blocked by the hindquarters of a mule. The lieutenant pointed out some of the landmarks along the way, starting with the peak of Jade Dragon Snow Mountain, at 18,500 feet, towering off to the north within the great bend of the Yangtze, the only one of the Rivers of Paradise that I’d not crossed, but which I’d now, at least, seen. The flight engineer then pointed out the Mekong, the Salween, and the Brahmaputra, the other three Rivers of Paradise, and far to the north I could see where all four of them poured down out of the Tibetan Plateau, flowing from the Roof of the World to bring their life-giving waters to farms, tea plantations, and rice paddies all the way from China to India, as if they were indeed coming down from paradise. But I reminded myself that the countryside through which we’d passed during these past few weeks had been turned into what had literally been a hell on earth. And even now, when peace had returned to the rest of the world, war was about to resume here in this lost Eden.