INTERLUDE: THE PENSACOLA CAMPAIGN

The local remnants of the Spanish Empire in North America were trapped among the devils. Americans threatened Florida from the north, Britain controlled the seas, and the defeated Creeks were an unpredictable factor.

Jackson was painfully aware of the British use of Pensacola as a base. He arrived in Mobile on August 27, 1814, amid rumors of a major British offensive on the Gulf Coast. Many Americans along the frontier saw Florida, the remnant of the Spanish Empire in North America, as rightfully American territory. This had already resulted in the Patriot’s War, a brief occupation of parts of East Florida in 1812. Spanish sales of munitions to the Red Sticks, and British use of Pensacola and smaller Florida ports as bases further enraged the Americans, but Governor Gonzalez Manrique was unable to resist the threat of a superior British force. The local British land commander, Major Edward Nicolls of the Royal Marines, discovered that many of the locals – including British merchants – were sympathetic to the Americans. He alienated Spanish and British citizens by seizing property and recruiting their slaves as soldiers.

|

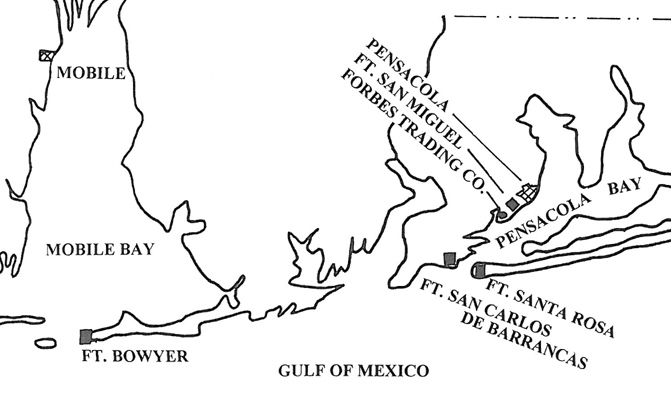

DAILY LIFE IN CAMP, THE PENSACOLA CAMPAIGN

Jackson, without authorization from Washington, attacked and captured Spanish Pensacola on November 7, 1814, disrupting both British use of the port as a base to supply the hostile Red Sticks, and British plans for land assaults on Mobile and New Orleans. In the foreground a Tennessee militiaman and a Choctaw scout perform camp chores – clothing repairs, casting lead shot, and making tinder for starting fires by heating cloth in a metal can. In the background Army regulars help train other militiamen, a major task for the regular soldiers under Jackson’s command. Military knowledge for both regulars and militia was gained largely from manuals like the one the officer is holding. In the foreground are typical camp items: provision barrels used for temporary storage, a personal effects chest, and a camp lantern. The tent fly to provide shelter from rain and sun would have been quite a luxury for the ill-equipped militia. |

PENSACOLA CAMPAIGN

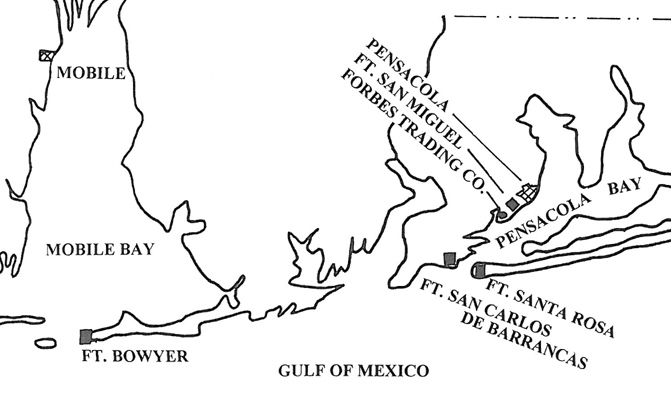

Without authorization, Jackson attacked the Spanish port of Pensacola, which was being used by the British to re-supply the Red Sticks. The British and their allies abandoned the small city, and in the retreat British troops looted the large British Forbes Trading Company facility, leading the company to support the Americans with intelligence and material aid. Ironically, the British destruction of the forts prompted Jackson to take his entire army to defend New Orleans. The initial attack on American positions at Ft Bowyer failed.

Nicolls also attempted to recruit Jean Lafitte and his Baratarian privateers. Lafitte forwarded a copy of a letter that detailed British plans for an attack on New Orleans to the governor of Louisiana, with an appeal for a pardon for his men.14

Nicolls and the naval commander of the expedition chose to first attempt the capture of Mobile. Tiny Fort Bowyer guarded the approach to the city. On September 13, 1814, the fort, garrisoned by US Army regulars, withstood a coordinated land and naval attack. The British land force retreated to Pensacola.

Jackson received no reply to his demands that Governor Manrique prevent the British from using Pensacola. He called up more militia and assembled a force of 520 Army regulars, 750 Choctaw and Chickasaw, and 1,200 militia and volunteers. Billy and the Deacon joined up with a group of dismounted cavalrymen from Colonel William Russell’s Volunteer Mounted Gunmen.

The Spanish garrison at Pensacola consisted of about 500 dispirited troops. In the face of American demands for the surrender of the city, Manrique vacillated, but on November 2 called for aid. The British naval commander refused to land his sailors, but Major Nicolls decided to fight for the small city.

The militiamen marched south from Fort Montgomery on the Alabama River through the sandy pine forests. Billy was awakened before dawn on November 6.

“Up, boys,” said the sergeant. “We’re goin’ to see the Spaniards.” The men ate a cold meal of hardtack and water.

At sunrise they set off with a detachment of Army regulars and three mounted officers. Crude cabins in the pine forest stood empty, the entire countryside seemed abandoned. But there were prints of moccasin-shod feet everywhere.

The path widened to a crude road, and the low buildings of Pensacola came into view. “Ain’t much of a town,” observed Billy. An officer laughed. “Biggest town around here. It’s got two streets.”

The officer unrolled a white cloth, and the mounted men rode out of the tree line. A puff of white smoke appeared near the edge of the town, and a musket ball whirred overhead. A ragged volley caused the officers to spur their horses back toward the shelter of the trees.

“Lieutenant,” ordered the senior officer, “go and inform General Jackson what has transpired. We will wait near that last crossroad.” Jackson soon appeared, visibly enraged. A captured Spanish soldier was sent into the town to offer terms of surrender, which were refused.

That night in camp outside the town, the militia and Choctaw molded balls and performed last-minute chores. Just before dark the captain assembled his company to provide last-minute instructions.

To avoid the British naval guns, Jackson kept a diversionary force near the bay, and in the predawn hours of November 7, marched his force through the scrub forest to the east side of the town. The assault was made by four columns, three of militia and one of Choctaw.

Billy’s company followed the regulars who would spearhead the attack. A Spanish cannon sited in the street at the edge of town got off one round, which went wide of the column. Billy pulled his weapon to full cock and fired at the town. Grabbing his tomahawk from his belt, he ran at the defenders with a blood-curdling scream. The Royal Marines operating the cannon abandoned it when the Spanish troops around them bolted.

The regular soldiers advanced at the double-quick, militia in a loose line on the flanks. Billy noticed a gaudily dressed Spanish officer running about in confusion with a white flag, and one of the American officers gave the order to cease fire.

The battle for Pensacola was over within minutes. The British fell back into Fort Barrancas, saved by the confusion that accompanied the Spanish surrender. The next day they boarded ships, blowing up the forts, carrying off slaves and property, and taking 200 unwilling black Spanish troops into forced labor.

Jackson received intelligence that the British would launch their long-planned assault on New Orleans. With the forts destroyed, Jackson abandoned Pensacola and set out for Louisiana.