Chapter Eleven

The Transformation from Freeport Lou to Frankenstein

1971–73

My direction had always been rock and roll—I saw it as a life force. My goal is to play Vegas … be a lounge act … be like Eddie Fisher … get divorced … have a scandal … go bankrupt … end up in Moscow, marry Connie Stevens, and read about myself in the National Enquirer.

Lou Reed

Chubby, shaggy-haired, twenty-nine-year-old Lou presented himself to British customs officers at Heathrow Airport as a musician on December 28, 1971. He did not look anything like a rock star, let alone the glitter rocker who would soon be the world-famous standard-bearer of a new movement. For a man whose image at the Factory had been pencil-thin behind sunglasses and black leather, being fat was the most blatant sign of an ambivalence to the task at hand.

Reed and his entourage checked into what was London’s most popular hotel for top-of-the-line rock stars, the Inn on the Park. An ultramodern American-style hotel, it was located on the same block as the London Hilton, overlooking Hyde Park. Throughout January, Lou and Bettye and Richard and Lisa lived in a world of their own focused on the making of the solo album and little else. Lou would walk around with Richard on one arm and Bettye on the other, introducing them to people as “my boyfriend and my girlfriend.” The threesome might have made a brilliant collaboration, but as it turned out, Bettye did not have the mind or strength to be Lou’s partner, and Richard was no John Cale.

Lou had often used the image of a chess game to describe his career. One of his daring moves on the board now was to record in London instead of New York. The decision made sense: In London he could avoid the prying eyes of RCA executives and get out from under the union pressure to use RCA’s New York studios. Yet, for a man who was proud of being a control freak he was taking an enormous risk in choosing to work in a scenario he knew nothing about and therefore could not easily manipulate.

Reed’s strategy of starting his campaign in London was smart in other ways as well. It would have been a mistake to launch his return in America, where his association with Warhol and the Velvet Underground was the kiss of death. He was also better known in Britain than in the United States. His work was highly appreciated in Britain, and the new generation of rock stars, spearheaded by Bowie, welcomed him like a hero. In London, where the atmosphere was tolerant, Lou was free to explore his sexual identity. England had a history of fondness for eccentrics and cross-dressers, who often played starring roles in music halls and pantomime. Lou would feel free to stretch the boundaries of convention in his music. Apart from refreshing himself by changing the backdrop, Lou chose to record in London because it was the most receptive city for rock experimentors. London studios were on the cutting edge and British producers and engineers appeared more willing to translate musicians’ ideas in a collaborative way. Given the many factors pointing to success, Lou’s arrival in London was as well placed, and played, as his entrance into the Factory six years earlier.

These factors did not, however, work in Lou’s favor. Despite five years of experience and a fifteen-month furlough to get ready for this step, Lou was ill prepared for his first solo recording sessions. Instead of showing up with a powerful collection of new works with which to stake his claim on the 1970s, Lou brought in unreleased VU tracks and castoffs from other projects. Surrounded by yes-men, Lou got no word of protest. The people working with him were more like enablers than collaborators.

His musicians, for one, were a lackluster group chosen for him by RCA. When Lou arrived in the studio, unpacked his guitar, and turned toward the microphone, he was astonished to discover, peering at him from behind their instruments, a (by Velvet Underground standards) B-list band: Rick Wakeman and Tony Kaye, two keyboard players from the progressive band Yes; Caleb Quaye from Elton John’s band; as well as Steve Howe and Paul Keough on guitars, Les Hurdle and Brian Odgers on bass, and Clem Cattini on drums. These men were orthodox professionals who knew how to play their instruments, but, as session musicians, they brought little spirit to the music. Lou found it difficult to work up a rapport with them. As a result, Reed, once described by John Cale as “a wild man on the guitar,” did not play a single note on his first solo album. Throughout the Velvets’ reign, his guitar had been an extension of himself. Now, that third arm was amputated.

Lou didn’t seem to care. As long as he could bark orders to a quiescent band, he was satisfied: “Making a really good record is very, very difficult and it’s a matter of control. If you don’t have the right musicians and you don’t have the right engineer, it’s very hard. But you have to start someplace. The situation is not always one where you can call the shots or even half the shots. I didn’t particularly know any musicians so it didn’t matter who you got. If they played what I told them to play, then it might be okay, and if they didn’t, then it wouldn’t.”

While Lou was sleepwalking through the recording sessions, Robinson was floundering at the control panel. Having scant experience as a producer, Robinson was confused by some of the more sophisticated British technology. Giving the impression that everything was under control, he assured Katz’s assistant, Barbara Falk, in a letter that month, “We are into technical cutting stages. As far as I can tell it is the best album I’ve done to date. Lou is in ecstasy.” Gerard Malanga, who visited Lou at his hotel near the end of the session, found him quiet and content in the encouraging presence of Lisa Robinson, who played the Warhol role in the collaboration, flattering Lou and assuring him that everything was “Great!” Lou, though, must have noticed that everything was not as cool as the Robinsons thought because he kept telling Richard, “This isn’t the way the record is supposed to sound, the album is not defined enough.” The truth, one observer noted, was that “he had not quite settled on a voice.”

“A lot of what I do is intuitive,” Reed said about making the album. “I just go where it takes me and I don’t question it.” This admission about his lack of direction, combined with the weak, raw material of the album, cried out for a strong collaborator. However, Lou avowed, “I’m not consulting anybody this time, it’s a solo effort with my producer, Richard Robinson.” He felt confident that “this was the closest realization to what I heard in my head that I ever did. It was a real rock-and-roll album.”

Just how ambivalent Reed felt about his solo career was emphasized near the end of the month when John Cale came to London and invited Lou to join him and Nico in Paris to perform at the Bataclan Club on January 29. Lou, who hated rehearsing, not only agreed to play with them, but spent two days going over the material with John in London. Richard Robinson videotaped Lou and John rehearsing, making music that ranked among their best collaborations. As one critic, James Walcott, described it: “Reed’s monochromatic voice, and Cale’s mournful viola, mixed with the dirgeful lyrics and the colorless bleakness of the video image turned a casual rehearsal into a drama of luminous melancholia. What was blurry before became indelibly vivid, and the Reed/Cale harlequinade melted away so that one could truly feel their power as prodigies of transfiguration. Listening to the Velvets, you may have been alone but you were never stranded.”

Lou also rehearsed for a whole day with Nico in Paris. The nightclub show, filmed for French television, was one of his happier experiences. Performing in a small, smoke-filled venue with his former soul mates, Lou took off on a few solo flights in the tradition of the nightclub greats. He noted later, “I always wanted to do a song like on the album Berlin that’s like a Barbra Streisand kind of thing. A real nightclub torch thing. Like, if you were Frank Sinatra [whom Lou greatly admired], you’d loosen your tie and light a cigarette. And when I was in Paris, that’s how I performed it. I didn’t play at all. I had John play the piano and I sat on a stool with my legs crossed. And during the instrumental break I lit a cigarette and I puffed it and said, ‘It was paradise. It was heaven. It was really bliss.’ I was just doing that Billie Holiday trip. Her phrasing, I mean that’s singing. I think [he said in one of the more perceptive comments of his career] I’m acting.”

Lou was so moved by the experience with Cale and Nico that he suggested the three of them get back together, but they turned him down. At the time, Nico had already released three solo albums with great critical success, and Cale had made real headway as a producer and solo artist on among others The Stooges’ first album in 1969. At the time, they both appeared to be in a stronger position than Lewis.

During January 1972 Reed had lived inside a bubble—waited on hand and foot in a luxurious hotel at the center of a circle whose sole reason to be there was he—doing what he liked best: writing, singing, and recording. As soon as he returned to New York on January 30, however, the bubble burst.

Dennis Katz was appalled by how bad the album was. “The production did not come out the way I’d anticipated it,” Katz explained. “It was much too sparse.” Everybody in Reed’s New York management organization agreed with Katz. “What are we doing wasting our time!” the salespeople at RCA screamed at Katz. “They made it clear that they were disappointed in Lou,” he recalled. “They rejected the direction—and specifically the production—of the first album.”

Listening to the album now, one can understand their concern. Whereas the record, titled simply Lou Reed, contained a number of fine songs such as “Lisa Says” and “Ocean,” the performance and the production paled considerably in relation to anything Lou had previously released. Part of the problem was purely technical. Years later, when Reed remastered several tracks from Lou Reed for the 1992 boxed set Between Thought and Expression, he discovered the album had not been recorded in Dolby, but Dolby decoded, which robbed it of its high frequencies.

Technological mistakes aside, the album’s artistic weakness arose from the fact that most of the songs were outtakes from VU albums that had sounded a lot better when Lou played them with the VU. The outstanding example is an outtake from Loaded, “Ocean,” on which John Cale had played backup in 1970 at Steve Sesnick’s invitation. The Loaded version, with Cale on organ and Lou in full command of an eerie and vibrant voice, was magisterial. The version on Lou Reed was dead by comparison. It was like comparing Janis Joplin singing “Bobby McGee” to Kris Kristofferson. Lou was very influenced by whomever he played with, and his inability to collaborate with people who were as good as or better than he had produced painfully obvious results on the album. In essence, the taut sound of Lou’s songs on Loaded was obscured by the wrong musicians and poor production on Lou Reed.

Lou Reed almost destroyed Lou Reed’s solo career before he got off the ground. The rock world was changing rapidly, and a lot of money was at stake for record companies, who were forced to make fast and merciless judgments. RCA’s executives were so dismayed by the poor quality of Lou Reed they considered canceling his second album. Matters were made even worse by the fact that, for the cover, Lou insisted they use an illustration of a bird next to a jeweled egg by the artist who did the covers of Raymond Chandler books.

Back in New York, Lou found himself in a confusing place with nobody he could really talk to. Money was tight. Lou and Bettye squeezed into a cubiclelike studio apartment on Manhattan’s Upper East Side on 78th Street, popularly known as the airline-stewardess ghetto. Lou was trying on different disguises. “His life with Bettye and his apartment seemed to provide a kind of domestic security that Lou needed to sustain him in his transition from cult-group figure to solo artist,” reported his friend Ed McCormack, who edited Fusion, a magazine that had recently published a number of Reed’s poems. Ed remembered Lou, accompanied by a nervous, battered-looking Bettye, sitting in his apartment at midnight wearing a pair of sunglasses, keeping his fears at bay by bolting down copious quantities of booze.

“He had the most horrible apartment,” recalled Glenn O’Brien, another writer Lou socialized with. “With shag carpeting going up the walls and really bad furniture. And Lou was boozing really heavy. He was a little bit more together, he didn’t seem so pathetic, but he must have been doing a lot of booze and pills. He was the first person I ever saw who was really shaky like that, having double Bloody Marys at noon. The first time I met Bettye she had a black eye. She was cute, but I remember her always having a black eye.”

The album was to be released in May, by which time it was Lou’s job to put together a band and tour the U.S. Lou faced the near impossible question: What musicians do you hire to play with when you’ve played in one of the greatest rock-and-roll bands of all time? Lou’s answer was to choose an unknown and unacclaimed band whose name, the Tots, said everything you needed to know about them. Not only were they pedestrian musicians, they were ugly and asexual. But the Tots provided Lou with exactly what he wanted—an unshared spotlight. No member of the band would question orders or arrangements, Lou would have total control. He also figured that teaching them his repertoire would be simple since the majority of his songs were repetitions and variations and stemmed off three, basic chords. Lou introduced the Tots as a great young and unknown band.

The ensemble made a nervous debut at the Millard Fillmore Room of the University of Buffalo. Lou’s performance was uptight, rigid, and tentative, according to Billy Altman, the student who arranged the show. Togged out in black leather trousers and jacket, Lou’s halo of ringlets hovered around a face covered by a layer of clown-white Pan-Cake makeup, lipstick and eye shadow. Having abandoned his guitar, Lou found himself thrust into the spotlight without the stage moves that are a crucial part of the lead singer’s repertoire. Lou seemed trapped between personalities. At one moment he seemed to be copying Mick Jagger, then suddenly he looked like Jerry Lewis. When Altman, who had published a glowing review of the concert in the local paper, visited him the following day, Lou was curt, the five minutes they spent together excruciating. Despite proclaiming that he would never commit suicide because he was “in control,” Lou was impressed by the suicide that month of the British actor George Sanders, who left a note explaining, “I’m so bored.”

In May, when the album Lou Reed and two singles, “Goin’ Down”/“I Can’t Stand It” and “Walk and Talk It”/“Wild Child,” were released, Dennis Katz’s worst fears were realized. Initially Lou Reed sold around seven thousand copies, an embarrassing result in an industry where fifty thousand to one hundred thousand was considered reasonable.

It was a telling moment for the Robinsons and their collective. Lou was the mascot of the New York underground, whose inhabitants would have benefited from his success. Loyal critics like Donald Lyons gushed in Interview magazine that Lou was “a classic romantic—the smell of his work is the smell of Baudelaire’s Paris—grappling, tempted, and sometimes happy, always human. It’s a wonderful album.” Robert Christgau gave it a B+ in the Village Voice, but added that it was “hard to know what to make of this. Certainly it’s less committed—less rhythmically monolithic and staunchly weird—than the Velvets. Not that Reed is shying away from rock and roll or the demimonde. But when I’m feeling contrary he sounds, not just ‘decadent,’ but jaded, fagged out.” “Edith Piaf he ain’t,” admitted the disappointed Lester Bangs.

Most reviewers lambasted the work. “The comeback album—the resurrection of [record company’s label] ‘The Phantom Rock’ itself—was one of the more disappointing releases of 1972,” wrote the leading British rock critic Nick Kent, in the New Musical Express. “Reed’s songwriting style has deteriorated—his dalliance with whimsical little love ballads are at best mildly amusing, at worst quite embarrassing, and always out of context.”

Lou expressed a desire to kill Kent, but his defense of the album was lukewarm. “There’s just too many things wrong with it,” he lamented. “I was in dandy form and so was everybody else. I’m just aware of all the things that are missing and all the things that shouldn’t have been there.” Nobody was willing to die for it and nobody claimed to be more upset than Sterling Morrison. “I really felt sad,” he recalled. “I thought, ‘Oh, man, you have blown it!’ He used to be one of the great rock vocalists, but either his voice had seriously deteriorated or he can’t or won’t sing anymore.” John Cale explained that the lyric about hiring a vet Lou sang at the end of “Berlin” was deadly serious. He noted that Lou would often get passionate about something everybody else found funny, then be highly offended by their laughter. But, particularly in light of the bad production of Velvets’ leftovers, he found the album lame.

To make matters worse, no sooner had Lou come rushing out of the gate with his first individual effort than he was unhorsed by the same hurdle the Beatles had come up against when they went solo—the specter of previous work. In Reed’s case the invidious comparison between his earlier and current work was made painfully obvious when his last night with the Velvet Underground at Max’s was released the same month. Live at Max’s Kansas City enjoyed better reviews and sales than Lou Reed.

***

At this awful juncture, Lou put into play one of the elements that would always set him apart from the pack. When in trouble, he had an ability to charm and attract powerful people who believed in and were willing to go to bat for him. Dennis Katz, Lou’s lawyer during the first half of 1972, was now leaving RCA and began to make overtures to become Lou’s manager. Katz’s offer coincided with increasingly tumultuous relations between Reed and Fred Heller, with whom Reed had an explosive personality conflict. Bettye also complained about Fred pushing her around at Lou’s shows. When Lou told Fred he was going to be replaced by Dennis, a lawsuit ensued, from which Lou extricated himself at considerable financial cost.

Lou now seized upon Dennis as a father figure, even though the two were roughly the same age. Poised, literate, happily married, and devoted to his career, Dennis represented a guiding strength. Lou would often visit him at his home in Chappaqua. Everyone around the two recalled with awe a friendship in which Lou initially never contradicted or challenged Dennis.

“I think Dennis liked the fact that Lou needed him and depended on him,” said Katz’s assistant Barbara Falk. “He really thought that Lou was fantastic. David [Bowie] was just starting to take off at RCA right after Dennis left. Now Dennis swung totally to Lou. I remember Dennis’s wife saying that Lou was so much better than David Bowie, he wasn’t all the frills and glitter and he was stark and black, he was the street poet. Being of the literary bent, one of the things that attracted Dennis to rock artists were their lyrics.

“Dennis started getting more interested in Lou, and when David Bowie expressed an interest in producing Lou, Dennis got even more involved. Dennis got more protective and there was more contact and a relationship developed. Lou’s father came up to the office and wanted an accounting or reporting—because Lou had had problems with the guy who came before. He was a quiet, nondescript, businesslike fellow. He came on his own and he and Dennis went to lunch across the street. Mr. Reed was concerned and Dennis was trying to assure him that Lou was finally in good hands.”

Considering that Dennis was so different from Lou, the strength of their bond was surprising. Falk described Katz as a bookish homebody: “He was very home-oriented and private, he didn’t like to go out at night, he wasn’t your typical rock-and-roller. He collected autographs and first editions. And he was very, very literary in his interests. That part of Lou interested Dennis, the fact that he had been published in the Paris Review, and the fact that they both read, which very few people in the rock world did. So they developed this strange relationship where they were both fascinated by each other’s lifestyle and they kidded each other about them and joked and put each other down.”

Lou loved the fact that Dennis was eccentric. He found that it was cool. He said, “He’s not like all the other guys, he’s got something in here.” And there was this strange symbiosis between them. They got along really well, but then I could never picture Lou staying overnight in Chappaqua—with his hours … But he used to stay over in this really nice house. And Dennis got up at seven, he fell asleep at eleven o’clock. I can also remember going out with the two of them to some gay bar and Dennis refused to go to the men’s room. He was fastidious. When they got along, they were a funny pair. And Dennis was always a placater and a builder-upper. He was articulate and he could speak to Lou. He would get frustrated with Lou, but, let’s face it, everybody would get frustrated with Lou. But Dennis always tried to make sure that Lou was aware of everything going on financially.”

During the time that Lou was befriending Katz, Andy Warhol also approached him with a job offer. Thriving in a dramatic period of his comeback from the 1968 attempted assassination, the artist asked Reed to write some songs for a Broadway musical to be produced by Warhol and Yves Saint Laurent. Lou recalled, “Andy said, ‘Why don’t you write a song called “Vicious”?’ I said, ‘Well, Andy, what kind of vicious?’ ‘Oh, you know, like I hit you with a flower.’ And I wrote it down, literally. Because I kept a notebook in those days. I used it for poetry and things people said.” Lou also wrote two other songs that along with “Vicious” would appear on his second solo album, Transformer: “New York Telephone Conversation” and “Make Up.”

Despite the support of these two men, Lou might have limped along indefinitely had it not been for the emergence of a new rock movement that swept him up in its vitality and high drama. Nineteen seventy-two had marked the entrance of glitter rock, which released sexual forces as potent as those let loose by the British pop explosion of 1964. In glam or glitter rock, male stars smashed open gender barriers by copying costumes and styles of camp 1930s film and stage icons. The results strained Lupe Velez and Mae West through a pastiche of drag queens and characters from the Warhol films Flesh, Trash, and Heat. Riding high on a creative wave brought on by the new gay liberation movement, glitter rockers—whether straight or gay—wore jewelry, makeup, high-heeled platform shoes, and sequined outfits. Yet, despite the feminine trappings, these rockers acted just as macho and adolescent as performers like the Rolling Stones, strutting and preening like little red roosters. Exemplified in England by David Bowie with his 1971 album Hunky Dory and hit single “Changes,” and in the U.S. by Alice Cooper, who had just released his album Killer, glitter rock changed rock’s look and sound, blowing open the doors for a number of new groups and movements.

Reed would have been hard-pressed to compete had he too not donned an attention-getting image. But he didn’t want to lose his hard edge or stoop to offering crass entertainment in the style of Alice Cooper. Lou hated Cooper’s glitzy outfits and goofy stage histrionics, which included wrapping a snake around his neck and spattering himself with blood. David Bowie’s smarter cooler demeanor appealed more to Lou. With his paler-than-pale skin, sensitive eyes, and floppy hair, Bowie looked appropriately androgynous. In Bowie, Reed would find a collaborator as important as Warhol—only much more commercial. And though at times losing sight of the thin line separating person from persona, Reed, like Bowie, would become a master of the seventies pageant.

In the summer of 1972, when Bowie returned to London from his triumphant American tour, bathed in the success of The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust (which had come out in June), he proposed to RCA that he produce Reed’s second album.

“David was very smart,” noted his wife, Angie. “He’d been evaluating the market for his work, calculating his moves, and monitoring his competition. And the only really serious competition in his market niche, he’d concluded, consisted of Lou Reed and—maybe—lggy Pop. So what did David do? He co-opted them. He brought them into his circle. He talked them up in interviews, spreading their legend in Britain.” David (who had included a musical tribute to the Velvets on Hunky Dory) saw Lou as “the most important writer in rock and roll in the world.”

According to Dennis Katz, RCA was receptive. “They had a lot of faith in Bowie because he co-produced both Hunky Dory and Ziggy Stardust with Ken Scott. So they were then willing to take another shot at a Reed album—assuming David was working with Lou.”

Tony Zanetta attended “another bar-mitzvah dinner” for David Bowie and Lou in New York at which they started talking about doing Transformer. Plans were made fast. David was still touring and planning on coming back to New York in September. They decided to record in July and August. “They wanted to work with Lou because they didn’t like the first album and didn’t think that it was what he should be doing,” said Tony Zanetta. “But it was a sensitive issue because of Richard Robinson.”

Lou’s decision to have Bowie produce his next album was a shock to Robinson, who had been the only member of Lou’s entourage to question Bowie’s motives in January. Richard had taken it for granted that he would be producing Lou’s second album, especially since Lou had told one interviewer, “Richard had the same goals I had. We knew we wanted the album to come out this way. We had it all plotted out before we even went to London.” But once Lou became aware that Richard’s involvement threatened to doom him to oblivion, he agreed to cut him from the team. “The Robinsons were rather possessive of Lou,” Glenn O’Brien recalled. “They had a big problem because they thought he should have been eternally grateful to Richard for giving him his big break.”

The Robinsons felt that they had brought Lou out of retirement and saw the move as the ultimate betrayal. When Richard was informed over the phone from Katz’s office that his services would no longer be required, he screamed that Lou was an “aging queen.”

“I can understand it,” said Barbara Falk. “Richard thought, ‘I brought him in, and it was my thing, and nobody wanted him, and part of my deal was that I would continue on …” He thought he had an understanding. Lisa actually didn’t speak to the Bowies for some time because of that—it was a big rift. Lou looked on her as the high priestess of the current rock scene. After the breach when they weren’t speaking, he’d say, ‘They’re little pop people,’ but he probably still read her religiously.”

Lou suddenly found himself closed out of Lisa’s collective. “I still love Richard,” Lou groaned to Ed McCormack, “but I’m not so sure he loves me anymore. But then, I wouldn’t really know what people think of me. I hardly see anyone anymore. There are dear friends who I no longer see, not because I don’t love them, but because I can no longer be a part of that whole hip scene. These nights I hardly go out at all, except down to the liquor store to buy another fifth.

“Sometimes I have this horrible nightmare that I’m not really what I think I am … That I’m just a completely decadent egoist … Do you have any idea what it’s like to be in my shoes?”

***

When Lou had left the VU, he had realized he did not want to be the kind of rock star Sesnick saw him as—a Beatle or a Monkee. David had shown him a way to be a star and carry his bisexuality as a weapon rather than a burden. When Lou flew to London in July for the August recording sessions, he immersed himself in the role with the glee he had felt as a newcomer at the Factory.

“Writing songs is like making a play and you give yourself the lead part,” Reed said in an interview about working with Bowie. “And you write yourself the best lines that you could. And you’re your own director. And they’re short plays. And you get to play all kinds of different characters. It’s fun. I write through the eyes of somebody else. I’m always checking out people I know I’m going to write songs about. Then I become them. That’s why when I’m not doing that, I’m kind of empty. I don’t have a personality of my own. I just pick up other people’s personalities. I mean seriously, if I’m around someone who has a gesture that’s typical of them, if I’m around them for more than an hour, I’ll start doing it. And if I really like it, I’ll keep it until I meet someone else who has something else. But I don’t have anything myself.”

Lou was dazzled by David, one of his brightest disciples. Lou was also mesmerized by David’s management machine and deft manipulation of his press and fans. For a few weeks, Reed soaked up elements of the character and influence of his charismatic friend, adding them to his own, evolving day to day. “I had a lot of fun,” Reed recalled, “and I think David did. He seemed quick and facile. I was isolated. Why were people talking about him so much? What did he do that I could learn? A lot of it reminded me of when I was with Warhol.”

The two of them cruised London’s seamy side. “Lou loved Soho, especially at night,” Bowie said. “He thought it was quaint compared to New York. He liked it because he could have a good time and still be safe. It was all drunks and tramps and whores and strip clubs and after-hours bars, but no one was going to mug you or beat you up. It was very twilight.”

By the time Lou and David got to hang out with each other that summer, Bowie had been praising Lou Reed to the sky for years. Now it was Lou’s turn to be bowled over by David and his Warhol-like world in the high-powered, fast-moving London rock scene.

“David is a seductive person and that is his MO,” explained Tony Zanetta. “And he used that with Lou because he wanted something from Lou. He looks you right in the eye and no one exists but you. But that’s only for a few minutes. We all went for it and I’m sure Lou did. And I’m sure Lou was ignored—not out of lack of interest, but because David was so busy. David was interested in Lou, but he wanted everybody. That’s what Ziggy was.”

Very few artists are capable of the generosity David Bowie extended to Lou Reed in the summer of 1972. As proof of his devotion, Bowie invited Reed to guest-star at his headlining show at the Royal Festival Hall on July 8, a benefit for Friends of the Earth. At the end of the set David brought Lou Reed, dressed in black, onstage to perform “White Light/White Heat,” “I’m Waiting for the Man,” and “Sweet Jane.”

After Bowie introduced Lou to British audiences, he held a day of press interviews at the top-of-the-line Dorchester Hotel, to publicize their music and images. It was at this moment that Lou Reed minced officially into glitter rock, entering in his Bowie-influenced Phantom of Rock persona, made-up and sparkling in Bowie’s designer’s jumpsuit, six-inch platforms, and black nail polish. With studied deliberation, the Phantom deposited his two cents into the gay-liberation kitty by tottering across La Bowie’s suite and firmly planting a kiss on David’s mouth. Then, announcing that Bowie, “a genius,” would be producing his next album, Lou withdrew. “People like Lou and I are probably predicting the end of an era, and I mean that catastrophically,” Bowie pontificated. “Any society that allows people like Lou and me to become rampant is pretty well lost. We’re both very mixed-up, paranoid people—absolute walking messes. I don’t really know what we’re doing. If we’re the spearhead of anything, we’re not necessarily the spearhead of anything good.”

Bowie then put himself at Reed’s disposal, offering to help in any way he could, instructing his wife, for example, to find Lou and Bettye a flat. David’s entourage was centered around his wife, Angie, and his guitar player, Mick Ronson. This triumvirate did everything they could to make Lou and Bettye comfortable in London. However, according to Zanetta, “Lou was pawned off on Angie; she was the human contact who would take care of things David didn’t want to deal with. And Lou was one of those things. I don’t know how involved David was with the record—I think it was mostly Ronson. He had a lot of things going on, gigs, touring, shows coming up, and recording. And the Mott the Hoople thing.”

Angela Bowie, who vividly remembered, “We felt extra special, intensely alive, incredibly alert,” was amused by Lou. “David introduced us and we shook hands, kind of … Lou’s greeting was a rather odd cross between a dead trout and a paranoid butterfly. My first clear impression of him was of a man of honor bound to act as fey and inhuman as he could. He was wearing heavy mascara and jet-black lipstick with matching nail polish, plus a tight little Errol-Flynn-as-Robin-Hood body shirt that must have lit up every queen for acres around him.”

Though they had very little money, Lou and Bettye moved into a furnished duplex in the posh London suburb of Wimbledon. Bowie was rehearsing for an upcoming tour, recording a new album of his own, and constantly working for greater international success, but took time to introduce Lou to people who would be useful to him. One contact, the writer and photographer Mick Rock, became Lou’s long-term friend. Everyone in Bowie’s set thought that Mick was brilliant and loved his work. “Mick,” one commented, “was a lot of fun because he was in the ozone.” In fact, Mick Rock was the perfect receiver for Lou Reed. Full of the good humor of the working-class Englishman straight out of a Charles Dickens novel, Rock possessed a mind that worked as fast as a camera, a charm that made people around him feel alive and at ease, and a detailed knowledge of Lou’s work. He became Reed’s primary social connection in London during the first half of the 1970s.

“Reed was staying in Wimbledon, a smart suburb of London favored by businessmen, film stars, and respectable hoodlums, and hating it there,” Mick revealed of his first visit to Reed. “A prowler, he needed the rootless, strung-out city for stimulation. Echoes of Baudelaire. A poet of pavement and splintered nerves. His psyche was fragile, withdrawn and nurtured on gin and mascara.”

Though he may have been uncomfortable in Wimbledon, Lou’s entrée into London’s rock world gave him a revitalized belief in himself. “People always come to me,” he told Mick Rock. “They have to because I have the power on them. I mean, they can’t stand me sitting here for too long doing nothing. Or they can’t take what I have to say. I like to make believe I’m a gun. I calculate. I look for a spot where I can really do it. Then they suddenly know I’m really a person.”

Not that he always had such a high opinion of himself. Later he would tell Mick, “I’m so dull really. That’s why I don’t write about myself. That’s why I need other people. I need New York City to feed off. The actual state of things.”

“Of the world?” Mick asked.

“No, just me. Fuck the world. I’m not interested in my problems or attitudes, ’cause other people’s are so much funnier.”

A week after the Dorchester press conference, Lou and the Tots set out on their first British tour with a show at the Kings Cross Sound in London. “When I saw Reed perform in London in the summer of 1972, the influence of Bowie’s theatrical, sexually ambiguous aesthetic was apparent; Lou wore black eye makeup, black lipstick, and a black velvet suit with rhinestone trimmings,” wrote one of Lou’s most intelligent chroniclers, Ellen Willis. “The album Transformer referred directly and explicitly to gay life and transvestism. The subject matter was not new, but Reed’s attitude toward it was—he was now openly identifying with a subculture he had always viewed obliquely, from a protective, ironic distance.”

Lou was criticized for copying Bowie. “I did three or four shows like that, and then it was back to leather,” he commented after the tour. “We were just kidding around—I’m not into makeup.” These tentative forays into the glam scene were merely the beginning, however. The new, rude Lou Reed relished being grabbed onstage by both girls and boys.

Though audiences in Britain soaked up Lou’s act, it was clear that he would have to work up some new songs to match it. The press was often critical of his material. “I’d rearranged my old songs just like Dylan and slowed some of them down, and the press branded the new versions as travesties of the originals,” Lou protested. “They’re my songs; surely I can do what I like with them. And I like them slower now.”

Although he was accused of aping David Bowie in his appearance and stage act, Lou continued putting the finishing touches on the Phantom of Rock. “I’m not going in the same direction as David,” Lou insisted. “He’s into the mime thing and that’s not me at all. I know I have a good hard-rock act, I just wanted to try doing something more—to push it right over the edge. I wanted to try that heavy eye makeup and dance about a bit. And how could anyone say I was letting my guitarist upstage me? He was doing it on my instructions. I told him to get up and wiggle his ass about and he did. Anyway, I’ve done it all now and stopped it. We all stand still and I don’t wear makeup anymore.” As an afterthought he added lugubriously, “They don’t want me to have any fun.”

***

Rock-and-roll records are born out of tension. By the time Bowie and Ronson took Reed into Trident Studios in August to record Transformer, which would turn Lou from an underground cult figure into a rock star, the collaboration was pitched on the edge it needed. On the one side was the authentic rock-and-roll animal Lou Reed. Fast, nervous, New York uptight, Lenny Bruce-like, sarcastic, hard, aggressive. On the other was the sensitive, high-strung Bowie, articulate, exotic, and strong, but not as sharp or hard as Lou. He was more of a dreamer. Between them stood the sturdy Mick Ronson—Ronno to his friends—from the shipbuilding town of Hull. Ronson could neither understand a word Lou said nor make his own densely crafted argot communicable to the wired little weasel. Lou seemed at times to be cracking up over convoluted private jokes told in another language altogether. Yet Ronno was the glue that cemented the three disparate figures to each other. “Ronson’s nasally electric guitar, which he played through a half-closed wa-wa pedal, provided Transformer with its instantly identifiable matrix,” wrote Jon Levin. “The underrated Ronson provided the string and brass arrangements, as well as the all-important piano parts, from the languid arpeggios of ‘Perfect Day’ and ‘Satellite of Love’ to the comedic ‘New York Telephone Conversation.’ Lyrics aside, the music is almost perfect: Herbie Flowers’s acoustic bass, acoustic guitars, a muffled electric, and jazzy brushes on the drums, all supported by Ronson’s subtle, chillingly simple violin arrangements. Reed has credited coproducer Ronson with making the greatest contribution to the completion of Transformer.”

The impact of Transformer’s sexual content has been forgotten. It is hard to conjure up the shock resulting from David Bowie’s confession of bisexuality in the Melody Maker interview of January 1972. The news catapulted Bowie into the front ranks of sexual role model for a generation or two as Ziggy Stardust (inspired by Warhol’s cast of the play Pork). He became an icon anyone could lust for. When David took his Ziggy Stardust act into the Rainbow, a huge former cinema in London, on August 19, Lou described the show as “the greatest thing I’ve ever seen.”

Bowie made bisexuality extremely hip, and Reed—who had sung lyrics such as “sucking on my ding-dong” as early as 1966—felt comfortable with the glam scene. In 1972, the lines “We’re coming out. Out of our closets, out on the street” (from “Make Up”) weren’t simply a camp gesture, but were associated with the Gay Liberation Front’s campaigning slogan—a rare political statement from the normally apolitical Reed.

The album had its rough edges and raw patches in the making. All three men were under a lot of pressure when they laid down its tracks. Bowie and Ronson, who were also recording with Mott the Hoople, were due to play concerts that month in London and New York. Their time was split between rehearsing and recording. For Reed, whose career depended on the outcome, every moment in the studio was vital. The fast, furious, drug-induced pace of their collaboration would have a lot to do with the album’s ultimate success.

David was characteristically modest about his intentions: “All that I can do is make a few definitions on some of the concepts of some of the songs and help arrange things the way Lou wants them. I’m just trying to do exactly as Lou wants.” Bowie was at the core of the production; it was his encouragement, like Warhol’s, that brought Reed to the fore as a solo artist.

Bowie, who was more fascinated by Warhol than Reed, pulled out of Lou’s nervous head a series of vignettes about the artist’s life that were worthy of Reed’s greatest role models—Raymond Chandler, Nelson Algren, and Jean Genet. Bowie got him to sing them at the top of his form. Enjoying himself, Reed was able to invent different attitudes and personalities for the album that found their way into the songs “Vicious” and “Walk on the Wild Side.” “I always thought it would be kinda fun to introduce people to characters they maybe hadn’t met before, or hadn’t wanted to meet, y’know,” Lou joked. “The kind of people you sometimes see at parties but don’t dare approach. That’s one of the motivations for me writing all those songs in the first place.”

“Last time they were all love songs,” he snapped, “this time they’re all hate songs.” Reed would play Bowie and Ronson the bare bones of the song, and together they would craft its eventual setting. Bowie and Ronson were attuned to what Lou’s songs needed, and their arrangements reinforced his material.

Whereas Cale had drawn together the lyrics of “Heroin” and all the great songs on the first album, that task now fell to Ronson. Ronson wrapped the lyrics in confident, sparring music that leaped out of the speakers and grabbed you around the throat, just as the Velvets’ music had. “Mick Ronson was really instrumental in doing the album,” one observer confided.

Ronson described their approach: “We are concentrating on the feeling rather than the technical side of the music. He’s an interesting person, but I never know what he’s thinking. However, as long as we can reach him musically, it’s all right.” Reed’s reaction to the collaboration with Bowie and Ronson was ecstatic. “Transformer is easily my best-produced album,” he exclaimed. “Together as a team they’re terrific.” “Transformer was a very beautiful album that David did out of love for Lou,” concluded Bowie’s friend Cherry Vanilla. “What you have to worry about is insanity,” Lou mused to friends later. “All the people I’ve known who were fabulous have either died or flipped or gone to India, Nepal, and studied and gave it all up, y’know, the whole trip. Either that, or else they concentrated it on one focal point, which is what I’m doing, which is what I think David is doing.”

Though Lou and David managed to create a brilliant mix, they attempted to outdo each other in performing the roles of “tortured, creative artists.” Angie Bowie, who frequently visited the studio, was often confronted with the sight of David curled into a fetal ball beneath the toilet bowl in deep depression, or Reedian tantrums so violent that she fled the studio before their velocity blew her out of the room. These throwbacks to childhood did not, however, faze the musical partners. Whenever David retreated to the john, Lou claimed he knew exactly how David felt and insisted that nobody disturb him. David in turn often talked Lou out of deep depressions. “David Bowie’s very clever. We found we had a lot of things in common. He learned how to be hip. Associating with me brought his name out to a lot more people. He’s very good in the studio. In a manner of speaking he produced an album for me.”

When Lou entered David’s world, the British charts had been dominated by Marc Bolan’s T. Rex, Gary Glitter, Slade, Alice Cooper, The Sweet, and Elton John. When Transformer was recorded and mixed, the single biggest star in the U.K. was David Bowie.

Whereas Reed’s first solo album was a jumble of material the Velvets never recorded and patchy love songs, Transformer was much more of a unified whole. Its subject, introduced by the album’s hit single, “Walk on the Wild Side,” was the world of Andy Warhol after the 1968 attempt on his life as detailed in “Andy’s Chest,” and in particular the polymorphous sexuality of the early seventies in Warhol’s films Trash and Heat.

Despite brief euphoric moments Lou had experienced during the making of Transformer, the album’s release marked the end of the Bowie–Reed collaboration. “Once that album was done, I don’t remember David ever mentioning Lou,” said Zanetra. “Or wanting to go see Lou or wanting Lou to come see this. David was always hot and cold with people. I think he was always intimidated by Lou. Because Lou was sharp and David wasn’t. David never pursued Lou the way he pursued lggy. He would come and go with Lou.”

In October, Lou and the Tots toured Britain. Lou’s Bowie-influenced stage act, combined with his new material, propelled him into the pop limelight. Dressed, as one observer put it, “in leather and charisma,” he delivered a series of devastating performances to rapt audiences. “I’m the biggest joker in the business,” he said. “But there’s something behind every joke.”

After the tour, and before Lou left London, Mick Rock did a photo session with him that would supply Lou with his first successful solo publicity image. Lou had always had an image problem. The VU had a glowering, grungy glamour that had not meshed that well with mass rock audiences. Lou and Mick came up with a brilliant solution. Combining his love for science fiction and horror and mixing it with his electroshock experiences, in Mick Rock’s cover photo for Transformer, Reed turned himself into a rock-and-roll Frankenstein.

In the photograph, the Lou Reed who had previously worn the black jeans, T-shirt, and rumpled corduroy jacket of a man uninterested in frills and stripped for heavy action, now appeared in the guise of a bisexual glitter rocker. Lou’s face was painted with a mask of deathly white Pan-Cake, and he stared past the camera with haunted eyes underlined by black kohl. Black lipstick delineated his new Cupid’s-bow mouth. His dyed jet-black hair was shaped in a stylish semi-Afro similar to Marc Bolan’s. Dressed from head to foot in a black jumpsuit, he also spotted black nail polish. This powerful image so matched the era it was hijacked by Tim Curry, who put it to use in his starring role in the 1975 cult musical and film The Rocky Horror Picture Show. It would shortly lead Reed to the peak of his commercial career.

***

When Dennis Katz and the people at RCA heard Transformer, they celebrated their decision to entrust Reed’s future to David Bowie. Convinced it would be a success and even yield a hit single, they prepared the way for its release and a subsequent tour by the artist. The album, with the seminal cover photo by Mick Rock, came out in November 1972.

Transformer was an enormous success and opened up a new world for Lou Reed. “Both lyrically and musically, Transformer was less intellectual and more pop than Reed’s work with the Velvet Underground,” wrote Ellen Willis, who originally gave the album a poor review. “At first I thought it was disappointingly conventional, lacking in the Velvets’ subtlety. That judgment turned out to be a joke on me; Transformer is easy to take as medicine that tastes like honey and kicks you in the throat. Take a song like ‘Perfect Day,’ a lovely, soft ode to an idyll in the park … or is it? But the album’s deceptively ordinary surface had commercial appeal, which was no doubt part of the point.”

To promote their hot new star, RCA came up with a clever label. They dubbed Lou Reed the Phantom of Rock. Ironically, this epithet underlined Lou’s greatest weakness: He had fashioned himself in the image of what his English fans imagined he was—a sexy wolverine, homosexual junkie hustler, and advocate of S&M. However, Andy Warhol, a man with a telling eye for these things, pointed out, “When John Cale and Lou were in the Velvets, they really had style. But when Lou went solo, he got bad and was copying people.” The figure he presented to the public didn’t really exist.

Bowie had insisted that RCA release “Walk on the Wild Side” as a single—against Lou’s wishes. Reed was sure it would be banned on the radio and didn’t want to repeat the pattern of media neglect he had experienced with the great Velvets albums that were never heard on the radio. Fortunately, Lou relented, and as the record company predicted, the single began to climb the charts, peaking at No. 16 on the U.S. charts in late winter of 1973.

However, somewhat to Reed’s chagrin, both in the U.K. and the U.S. the Bowie–Ronson influence was given more credit than Lou for the success of the work. “Thanks to their intelligence and taste,” Tim Jurgens wrote in Fusion, “Lou Reed has found the perfect accompaniment to such flights of fancy that he’s been lacking since John Cale went his own way.” And the Village Voice noted that “you can cut the atmosphere surrounding each song with a knife … and the clue to this album’s appeal lies in … a mix that has a chance of startling the listener and touching our common humanity.”

The album rode the wave of gay liberation and the sexual awakening of the early seventies, so Lou became a mascot of the burgeoning gay community. “What I’ve always thought is that I’m doing rock and roll in drag,” he stated. “If you just listen to the songs cursorily, they come off like rock and roll, but if you really pay attention, then they are in a way the quintessence of the rock-and-roll song, except they’re not rock and roll.”

Referring to another song, “Make Up,” he commented, “The gay life at the moment is not that great. I wanted to write a song which made it terrific, something that you’d enjoy. But I know if I do that, I’ll be accused of being a fag; but that’s all right, it doesn’t matter. I like those people, and I don’t like what’s going down, and I wanted to make it happy.”

Not everyone bought this new act quite so unquestioningly. When Transformer was released in the U.S., Lisa Robinson got everybody in her writers’ collective to give it a negative review. “As long as he played ball with Lisa and Richard, everybody supported him,” recalled Henry Edwards. “But if you pull the reviews of Transformer, you have a little story, because she single-handedly turned the press against him. And she got everyone to pan his album, including me. And that’s a good story, I think. No one thought at that moment he had a future. Everyone thought that he was a pop artifact to be manipulated—he was almost a golden oldie in a very short period of time. And he was desperate … I do feel guilty about writing a bad review of his album for the Times. I did what everybody else did—we fucked the album.”

“What’s the matter with Lou Reed? Transformer is terrible—lame, pseudodecadent lyrics, lame, pseudo-something-or-other-singing, and a just plain lame band,” wrote Ellen Willis in The New Yorker. “Part of Reed’s problem is that he needs a band he can interact with, a band that will give him some direction, as the Velvets did, instead of simply backing him up—in other words, not just a band but a group.”

Andy Warhol was quick to realize that “Walk on the Wild Side” was the single strongest piece of publicity he could use for his trilogy of films starring various drag queens and Joe Dallesandro—Flesh, Heat, and Trash. “Walk on the Wild Side” would become the No. 1 jukebox hit in America in 1973, and every time it played in a restaurant or bar or came wafting out of an apartment or car, it reminded everybody that Warhol’s movies were playing nearby. Warhol was happy about that, but it reminded him that Lou had now twice tapped into the Factory for material—where was the money Lou owed him from the first album? Thus, while embracing Lou publicly in his democracy of success, Andy harbored a hard-boiled resentment.

***

Lou was traveling too fast to notice. The year 1973 proved a momentous one in Reed’s professional and personal life. As Transformer sales mounted—it would take six months to peak—Dennis Katz and the RCA machine swung into action, sending Lou out on a seemingly endless tour that winter. In January, at his first New York solo show at Alice Tully Hall, wearing black leather jeans and jacket, he was, by all accounts, electrifying.

In February, to everyone’s surprise, the sexually ambiguous Reed, who thought of himself as a knight, who believed in pretty princesses and sparrows, married the woman another part of him looked upon as a Stepford wife. It was, he would later say, a pessimistic act. David Bowie was married, Mick Jagger was married. Maybe, Lou figured, it was the hip thing to do. “Yes, he’s got the princess; she’s Jewish, she likes making homey things,” noted one skeptical friend. “He needed a companion tucked away to be there when he needed them, but Bettye really didn’t understand him at all. He needed a person he could joust with, and ultimately Bettye really couldn’t play the game. She’d be very boring. That’s why he always ended up hitting her. He would never hit anybody who would smack him back.”

Katz soon added to Reed’s team his assistant Barbara Falk, who would be Lou’s road manager through the mid-seventies and the indispensable member of his support team. In those days it was unusual for a woman to have such a powerful role, and Barbara suffered from both the macho businessmen who ran the rock-concert scene and Lou’s wife, who was understandably jealous of another woman usurping her role as Lou’s baby-sitter. However, Barbara Falk, who possessed seemingly unlimited energy and a tough sense of humor, found herself enjoying the wild ride that was Lou’s life in those intense, successful years.

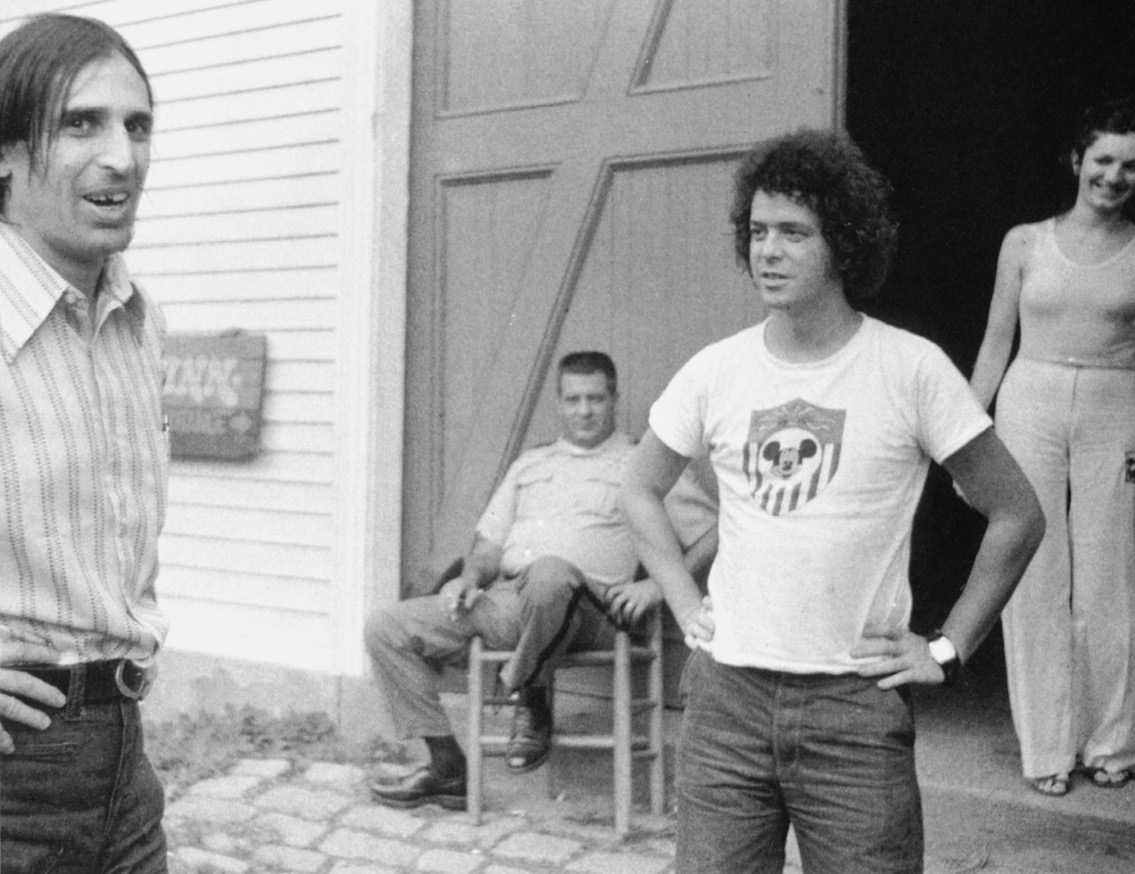

Mickey Ruskin visiting Lou Reed and Barbara Falk prior to Lou’s concert at the Music Inn, Lennox, in the Massachusetts Berkshires where Mickey maintained a country home. Summer, 1973. (Gerard Malanga)

In 1973, Lou and his band played three to five concerts a week, for fees ranging from $6,000 to $7,000. Dennis Katz took 20 percent off the top. William Morris took 10 percent off the top. Barbara Falk, who collected and distributed the money, recalled that she was paying twelve people per diems of $100 per week: “There must have been money owed—rehearsal money to be paid. Guitars. It never seemed to me that there was enough. I used to do these budgets. There were as many expenses as there were receipts, and then some. Rent-a-cars or limos, hotels. In Europe and Asia, sometimes the promoter would pay hotels and cars; in Australia, we would get maybe $5,000 a gig. They paid flights. I never got paid all my salary. Then there was the accountant and the IRS. The accountant dealt with them; we never put money aside for them. And Lou could spend a lot on the road. I was doling it out, very petty cash. He’d come up to me with his hand full of receipts. I used to have Lou sign things like, ‘Before money is paid to Lou, such and such amounts must be paid to Transformer, Inc.’ He read what was written and he could usually quote it back to me. I remember thinking of Lou that it was so sad that here was this guy with records and fans and all this, and he was living in this little sublet of a place with rented furniture … And coffee ice cream.”

To begin with, she genuinely adored Lou, who had a great sense of humor. He joked a lot. With a gift for mimicry, he would make fun of politicians, audiences, promoters, record-company people, and deejays. All were targets. She also quickly learned to get along with and respect Bettye, who was so obviously devoted to Lou. Transformer kept them pinned to the road for the next four months. By March 1973, Lou had reached a peak of success with his barnstorming tours turning into chaotic rock events. Although he had never possessed the charisma of Bowie or Jagger, Reed played a great rock-and-roll show. Above all, despite the chaos, the pressures, and the tight budgets, they all managed for the most part to have fun.

During one performance at Buffalo on March 24, Reed was bitten on the bum by a fan screaming, “Leather!” “America seems to breed real animals,” Lou said afterward, laughing.

“The glitter people know where I’m at, the gay people know where I’m at,” he explained. “I make songs up for them; I was doing things like that in ’66 except people were a lot more uptight then.” Barbara’s favorite memory of the Transformer tour was Lou’s being arrested onstage in Miami for singing “sucking on my ding-dong” while tapping the helmets of the policemen guarding the front of the stage with his microphone. As Lou was led away by a big cop with a serious expression intoning, “This man is going to jail,” Lou could barely control his hysterical laughter.

The zenith of Lou’s commercial success came between April and June of 1973 when Transformer and its single “Walk on the Wild Side” peaked, first in the U.S., then on the U.K. charts. Lou Reed was finally a pop star, but as the initial excitement of success waned, Reed considered the cost of stardom. Ever since Transformer, Lou’s audiences had come to expect the “son of Andy Warhol,” a manufactured cartoon character Reed had never been comfortable with, but had nonetheless used to resurrect his flagging career. He was trapped in the Bowie-inspired Phantom persona, and much of his celebrity was tempered by comparisons between the two.

“It did what it was supposed to,” stated the Phantom of Rock. “Like I say, I wanted to get popular so I could be the biggest schlock around, and I turned out really big schlock, because my shit’s better than other people’s diamonds. But it’s really boring being the best show in town. I took it as far as I could possibly go and then o-u-t.”