Chapter Thirteen

The Nervous Years

ELECTRICITY AND THE CELL STRUCTURE: 1974–76

Life, as I had come to know it, had made me nervous.

Lou Reed

Lou was terrific at putting together a collaborative relationship, but as soon as it succeeded, he had to subvert it. This need to demolish collaboration, his Achilles’ heel, would soon find its way into his relationships with Steve and Dennis Katz. The Katz brothers had been responsible for maneuvering him onto the international rock charts. Now Lou would pay them back.

As a Jewish man of the fifties, Lou knew that the best way to upset Dennis Katz would be to taunt him for his interest in Nazi memorabilia, and that the best way to taunt him was to flaunt Nazi paraphernalia himself. To accomplish this new affront, Lou had his hairdresser shave off his locks and on the left and right sides of his skull chisel, into his new military crew cut, Iron Crosses that bore an unmistakable likeness to Nazi swastikas.

“Dennis and Lou did have a fall-out when Lewis appeared with those Nazi crosses in his hair,” recalled Barbara Falk, who made Lou wear a hat whenever they went out. “We were worried when we first saw him like that, but what can you do? Lewis is such an extremist.” At times, Lou’s bizarre behavior and street-creep image broadened to such infantile and comic-strip proportions that people laughed at him, whether he wanted them to or not.

Lester Bangs had a friend working as a busboy at Max’s Kansas City: “The guy called me up one day. ‘Your boy was in again last night … Jesus, he looks like an insect … or like something that belongs in an intensive-care ward … almost no flesh on the bones, all the flesh that’s there’s sort of dead and sallow and hanging, his eyes are always darting all over the place, his skull is shaved and you can see the pallor under the bristles, it looks like he’s got iron plates implanted in his head.’”

One reason for Lou’s extreme acting out was his frustration about having to fulfill his promise to RCA to deliver the two promised commercial albums—Rock ’n’ Roll Animal and Sally Can’t Dance. With Steve Katz once again to produce, RCA was sure they’d have a winning product. Yet in their plans and profit–loss calculations, they failed to factor in Lou’s seething ire. In spring 1974, as soon as Lou started work on Sally Can’t Dance, his resentment spilled out.

“I slept through Sally Can’t Dance,” Reed boasted. “I did the vocals in one take, in twenty minutes, and then it was good-bye. They’d make a suggestion and I’d say, ‘Oh, all right.’ I just can’t write songs you can dance to. I sound terrible, but I was singing about the worst shit in the world.”

Lou felt Sally Can’t Dance was a mistake and that RCA had him up against a wall. As he saw it, the company heads were in cahoots with the Katz brothers to milk him for what he was still good for. Worse, they were trying to make him sound like Elton John! While halfheartedly fulfilling their expectations, Lou desperately held on to his identity. “Sally Can’t Dance … with all the junk in there, it’s still Lou Reed.”

According to Steve Katz, Lou spent the majority of his studio time in the bathroom. Katz was becoming increasingly impatient. One weekend when Lou was staying at Katz’s house in Westchester, Steve “accidently” walked into the bathroom and caught Lou injecting methedrine. Like his brother Dennis, Steve genuinely liked and respected Lou, but began to see that drugs were taking a toll on him. Even though Lou would regularly stop taking speed to clean out his system and follow a rigorous course of diet and exercise, his personality and work were being negatively affected. “We all loved him and understood him and tried to help him. But he simply refused to be there. The drugs were becoming just too much for me to deal with.”

To make matters worse Lou was so desperate for money he constantly hit up friends for cab fares and restaurant bills. His behavior was surprising for a man who had two international albums and a single on the charts. The truth was that Lou’s separation from Heller, divorce from Bettye, drug bills, and profligate spending habits had wiped him out. Never one to tackle financial matters like an accountant, Lou blamed the man who was handling his money, Dennis Katz. As Barbara Falk saw it: “Lou would say, ‘Dennis doesn’t get it and he’s got to have all the money.’ And then he became even more paranoid, there was a conspiracy to manipulate him and his money—full-blown!

“By then Dennis saw the handwriting on the wall, because that last year [1974–75] he was very particular about everything. And I remember when Dennis negotiated the publishing agreement with RCA where it was a lot of money, and they got twenty percent, then there were taxes, and there was very little left for Lou. The man had no real assets.”

Steve Katz had always taken a supportive attitude toward Lou, but he could not supply him with the creative foil that Cale, Warhol, Bowie, and Ezrin had. Steve echoed Blue Weaver: “As an artist, Lou was not totally there. He had to be propped up like a baby with things done for him and around him.”

Nobody could escape Lou’s wrath. Not content with savaging his manager, his producer, and his musicians, Lou dragged Nico into his circle of torment. Back in 1973, Lou had told Nico that Berlin was about her. She responded so favorably that she reignited Lou’s passion. When he showed friends an affectionate five-page scrawled letter from the Parisian foghorn, Lou’s face split into a shit-eating grin as he raved that Nico’s albums Desertshore and The Marble Index and her live version of “The End” were “incredible.” Nico was not only a real star but a whole galaxy unto herself.

Now, a year later, Lou announced that he would produce an album of his songs by Nico. No sooner had this obsessive notion taken root than Lou threw the whole operation into high gear and dispatched a ticket to the poor, spooked-out Nico. Since last seeing Lou, the former beauty had become a penniless junkie who clung to remnants of the 1960s philosophy. In March 1974, inflamed once again by the notion that the Prince of Stories would rescue her from oblivion, Nico found herself strapped into a jumbo jet high over the Atlantic clutching her harmonium, her candles, and her drugs.

In an uncharacteristic move, the moody Lou invited the hapless chanteuse to stay with him in his pied-à-terre on East 52nd Street. She set her few belongings among his two electric clocks, each of which told a different wrong time, his stacks of electronic equipment (Lou was an early and avid fan of video games), his signed Delmore Schwartz volumes, his first editions of Raymond Chandler, from which he constantly quoted and appropriated words, his pints of coffee ice cream and cartons of Marlboros, and, of course, his supply of liquid amphetamine.

No sooner had Lou gotten Nico established in his spot than he embarked upon the task of dismantling her personality. His first act of cruelty was to deny her access to his amphetamine while letting her know how well supplied he was. She was tortured by a blissed-out Lou from whom she received a kind of contact withdrawal. When he had the wan diva just where he wanted her, trembling and in tears, he allowed her to have a tiny taste of his medication while he sat back and watched her dissolve.

To add to his amusement, Lou made a point of filling his apartment with a motley assortment of people: inarticulate and exhausted engineers lay sprawled across the furniture in various states of ugly-snoring sleep; eager young journalists astonished to be in the company of two living legends. According to Nico’s blurred account of the three days she spent holed up with Lou, her final exit was precipitated by Lou’s torturing her one too many times. Having been raped as a child amid the ruins of Berlin by a sergeant in the U.S. army, she lived in fear of male violence. She fled the chic doorman building, Lou’s meanness, and any chance of being with Lou again. In her three-day stopover, Lou had succeeded in bringing her to her once proud knees and, having done so, evidenced a total lack of interest in her for the rest of her short life. He not only avoided producing a single track by her, but he refused to write or give her any more songs. The Lou Reed–Nico debacle marked a decisive turning point in her career, which plunged downward from its already low point.

Lou’s harsh treatment of Nico occasioned at least one furious phone call from Cale, who harbored the Nico episode as a bone of contention between them throughout the decade. “Right through the seventies I hoped Lou would write her another song like ‘All Tomorrow’s Parties,’ ‘Femme Fatale,’ or ‘I’ll Be Your Mirror,’ but he never did,” Cale said. “I’d tell him I was working with Nico on her new LP, whichever it was, and he’d just say, ‘Really?’—nothing more, not a flicker of interest. He could have written wonderful songs for her. It’s a shame and I regret it very much.”

In April, seeking friendship elsewhere, Lou took a trip to Amsterdam to visit the brother and sister he had befriended the previous year and collect an Edison award for Berlin. However, he returned in three days, his anger and frustration flashing on dangerous levels. He had, he told one friend bitterly, made another mistake.

With Nico gone, Lou turned his attention to Barbara Hodes. Barbara had lived with him intermittently since early 1974, but she had known him since 1966. A sexy, intelligent woman in the fashion business, she offered him loyalty and support and was much closer to his level mentally than Bettye had been. He never forgot how she had sought him out during his 1971 exile and encouraged him to make a comeback.

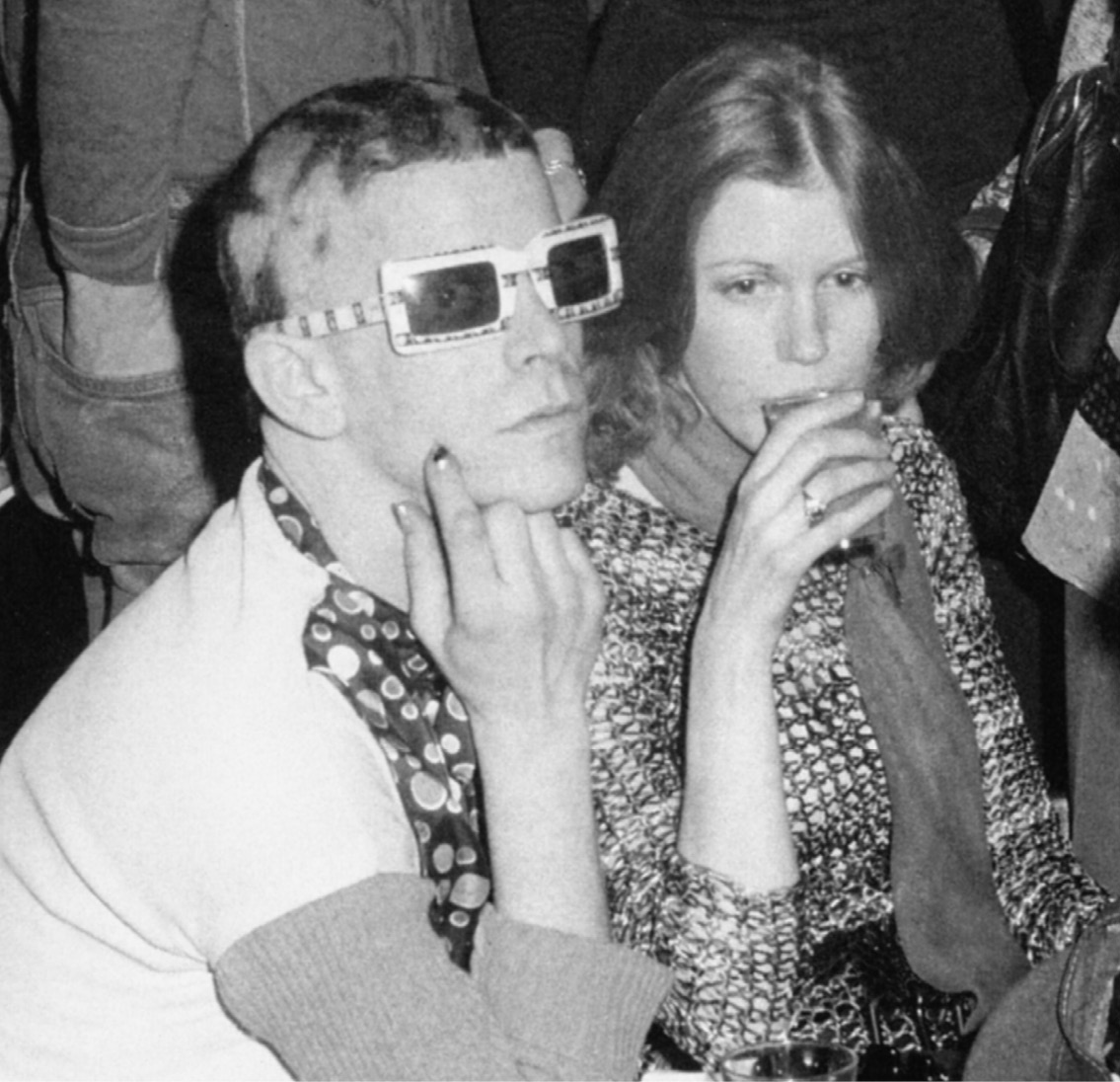

Lou with Barbara Hodes in New York, 1974. (Bob Gruen)

Lou brought the full force of his personality to the rock-and-roll stage that year, the only place he could really unleash himself. In May and June, accompanied by an entourage of twenty-four people, including Hodes, Reed embarked on a tour of Europe that took him through Sweden, Denmark, the Netherlands, Britain, Belgium, France, and back to Britain. The climax of each show was Lou’s rendition of “Heroin,” to which he now added a theatrical twist. Extracting a syringe from his pants pocket and lashing the microphone chord around his skinny arm, he mimed the ritual of injecting the deadly poison. Although this was an act, Reed made it so convincing that some press people vomited. Others feared for his life. The image of a skeletal, peroxide-blond Lou Reed shooting up onstage became one of the emblematic images of rock and roll in the early 1970s.

“Lou Reed is the guy that gave dignity and poetry and rock and roll to smack, speed, homosexuality, sadomasochism, murder, misogyny, stumblebum passivity, and suicide, and then proceeded to belie all his achievements and return to the mire by turning the whole thing into a bad joke,” wrote Lester Bangs in his most famous definition of his hero and bête noire. “Lou Reed is bound to be the best rock-and-roll star in America for the next five years, at least,” wrote one addled, if accurate, devotee in Philadelphia’s underground weekly, The Disturbed Drummer.

Having alienated Nico and Barbara, Lou desperately needed a companion who could keep pace with him as the pace quickened. Like his mentor Lenny Bruce, Lou had a little-boy side to his character who was frightened of being left alone lest he inadvertently do himself, or the building, harm. In fact, throughout the most dangerous years of his life, Lou would be alone only when he prowled the streets at dawn looking for an angry fix.

That autumn, back in New York, Lou met a tall, exotic drag-queen hairdresser from Philadelphia named Rachel (née Tommy). Rachel, a stunning half-Mexican Indian raised in reformatories, prisons, and on the streets, would become his nursemaid and muse through the mid-seventies.

“It was in a late-night club in Greenwich Village,” Reed later rhapsodized to Mick Rock. “I’d been up for days as usual, and everything was at the superreal, glowing stage. I walked in and there was this amazing person, this incredible head kind of vibrating out of it all. Rachel was wearing this amazing makeup and dress and was absolutely in a different world to anyone in the place. Eventually I spoke and she came home with me. I rapped for hours and hours, while Rachel just sat there looking at me, saying nothing. At the time I was living with a lady and I kind of wanted us all three to live together, but somehow it was too heavy for her. Rachel just stayed on and the girl moved out. Rachel was completely disinterested in who I was and what I did. Nothing could impress her. He’d hardly heard my music and didn’t like it all that much when he did.”

“I thought Rachel was a mermaid,” Lou wrote in a poem, “The Chemical Man.” “Fins on Second Avenue. Will these pills bring relief. I am the chemical man.” “Imagine,” urged Steve Katz, “a woman in a man’s body, getting by as a juvenile delinquent. Understanding Rachel was a question of understanding a person’s orientation. I found her wonderful, and very quiet. That whole thing about, was Lou a homosexual, was he straight? … Rachel was physically gorgeous for any sex. Straight men were coming on to her all the time.”

From Shelley Albin through Nico, Bettye, and Barbara Hodes, Lou maintained a pattern of dating blonde-haired women with theatrical personalities. Rachel introduced an abrupt change. Not only was this a guy—very evidently a guy when he would stay up for a couple of days, forget to shave, and be drinking—but Rachel’s coloring was dark and brooding. What Rachel had in common with her predecessors was a complete acceptance of Lou Reed across the board, an adoration of the little boy in him, and, most important of all, stamina. “I enjoy being around Rachel, that’s all there is to it,” Lou explained. “Whatever it is I need, Rachel seems to supply it, at the least we’re equal.”

According to Bob Jones, “Lou was having a sexual relationship with Rachel. Rachel would come out of the bedroom with just a wrap around her and Lou would have just come out. They slept in the same bed, Rachel slept naked in the bed. Speed is the biggest aphrodisiac. Also, you can go for hours. It is very tactile and very erotic. You make out for two hours without coming, and you want to fuck daily. So I think Lou was having sex. There was never any talk about having sex, but it would be inconceivable that he would go three weeks without sex. In fact, it would be inconceivable to go a week without sex. Inconceivable.”

With Rachel around, Lou never had to be alone. She did not speak much, but when she did, she put it across. Lou knew how to use her and benefited enormously from the relationship. “I think Andy’s fascination with drag queens was behind Lou’s interest in Rachel,” said one close friend. “The thing that Lou comically got wrong was that Rachel wasn’t a Warhol drag-queen type. The Warhol drag queens had a feminine side, or a drag-queen side. Rachel was sort of Native American, there was a very stone-faced-Indian aspect to Rachel. Rachel didn’t really have a woman’s attitude.”

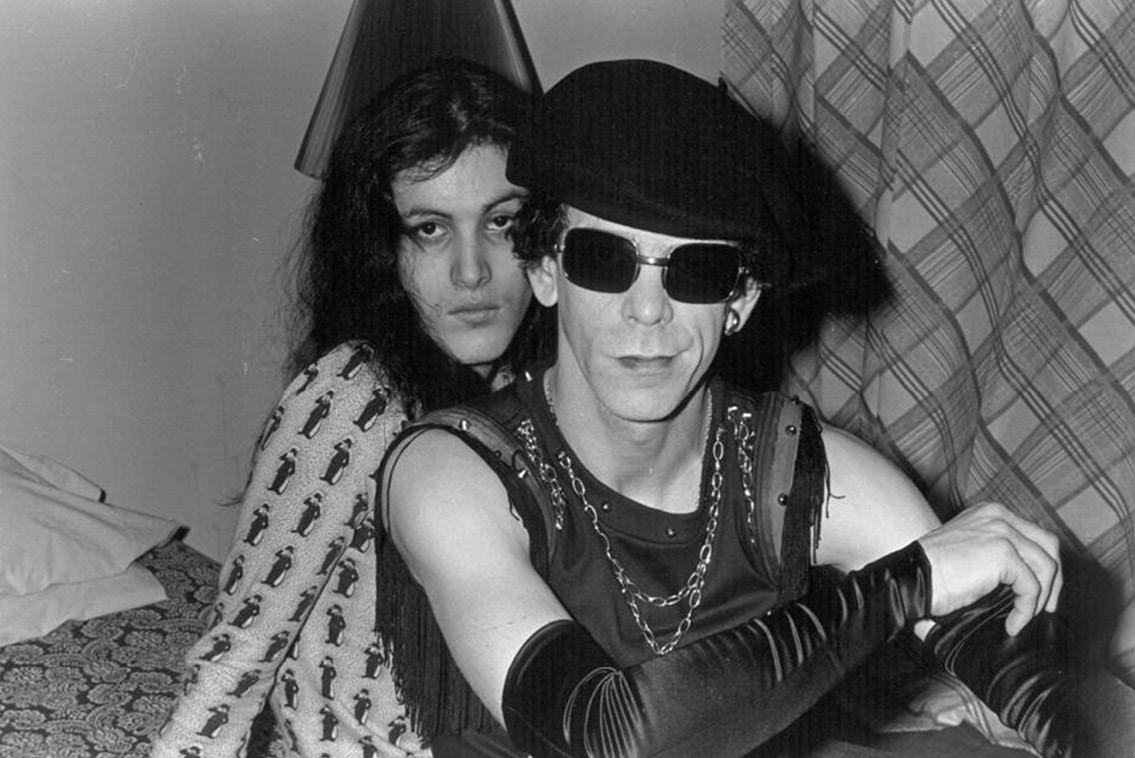

Mick Rock took a photograph that captured their relationship: clad in matching black leather, tottering on pencil-thin legs, the couple embrace. Lou in front faces the camera with a stoned smile on his face, Rachel, with a black hank of hair to her shoulder blades, supports him with a look of serene passion, her hands cupped possessively over his cock and balls.

Those who met Rachel found a tall, sweet person with a stoic nature. “In my experience of Lou,” longtime friend Dave Hickey wrote, “all these supposed digressions from the ‘norm’ were just bullshit. Anyway, if you took that much speed for that many years, you don’t know what the hell you are. Physically, you cannot get an erection. Whenever he’d start talking about his prowess, I’d know for sure he wasn’t getting it up, and therefore going to extremes. Psychologically I don’t think he’s oriented one way or the other. But he had the brilliance to dip in and out of deviance and play with it, make an illusion of it.”

Lou with Rachel, his muse from Metal Machine Music through Take No Prisoners and the subject of Coney Island Baby, 1975. (Gerard Malanga)

However, Lou’s sexual preferences had become important to his fans. Reed’s roadies were constantly asked if their leader was bi. “Bi? The fucker’s quad!” one joked in a bon mot that bounced around the rock world.

One observer believed some of his more outrageous behavior was a deliberate ploy to boost his hard-edge image. Commented Hickey, “He was careful to observe all the feedback the ‘Lou Reed persona’ got in the press. He read an enormous amount of magazines. He knew he was carrying the weight of his image of the Velvet Underground; he knew Lou Reed had to be Lou Reed. If Lou Reed is supposed to take drugs and have a weird sex life—well, then, it has to be.”

When Sally Can’t Dance was released in August 1974, it got a lot of press. “Lou is adept at figuring out new ways to shit on people,” wrote Robert Christgau in the Voice. “I mean, what else are we to make of this grotesque hodgepodge of soul horns, flash guitar, deadpan song-speech, and indifferent rhymes? I don’t know, and Lou probably doesn’t either—even as he shits on us, he can’t staunch his own cleverness. So the hodgepodge produces juxtapositions that are funny and interesting, the title tune is as deadly accurate as it is simply mean-spirited, and ‘Billy’ is simply moving, indifferent rhymes and all. B +.”

“‘Billy’ is unusual even for unusual Lou,” wrote Paul Williams in the SoHo Weekly News. “It’s a ballad about an old school friend and what became of him—and, by extension, about what became of Lou as well. It works. This album, with ‘Kill Your Sons’ and ‘Billy,’ is among other things an acknowledgement of Lou’s middle-class Long Island roots.”

In an open letter in Hit Parader, Richard Robinson revealed an unlooked-for empathy, calling Katz’s production “admirable” and telling Lou that it was “the closest thing you’ve been to being heard in some time.” But Robinson regretted Sally’s lack of depth, energy, and rock-and-roll craziness, which had him virtually unable to distinguish one track from another.

As if to mock everything Lou stood for, Sally Can’t Dance became Reed’s biggest-selling album internationally and stayed on the charts for fourteen weeks, becoming the only American Top Ten LP of his career.

With Sally’s success, Lou became even more disillusioned with the charade his career had become, exhibiting a new level of raw self-loathing. During interviews at the time, Reed either went into Warholian catatonia or degenerated into verbal war. Lou’s cynicism reached its zenith when he said to Danny Fields in Gig magazine, “This is fantastic—the worse I am, the more it sells. If I wasn’t on the record at all next time around, it would probably go to number one.”

After the album came out, Lou denigrated it, the musicians, and the producer. However, as Katz pointed out, Lou would work with some of them for years. According to Lou, “Sally Can’t Dance wasn’t a parody, that was what was happening. It was produced in the slimiest way possible. I like leakage. I wish all the Dolbys were just ripped out of the studio. I’ve spent more time getting rid of all that fucking shit. I hate that album. Sally Can’t Dance is tedious. Could you imagine putting out Sally Can’t Dance with your name on it? Dyeing my hair and all that shit? That’s what they wanted, that’s what they got. Sally Can’t Dance went into the Top Ten without a single, and I said, ‘Ah, what a piece of shit.’ … I like the old Velvets records. I don’t like Lou Reed records.”

Reed attempted to justify the animosity he generated with a Warholian protestation of innocence. “I’m passive and people just don’t understand that. They talk and I just sit and I don’t react and that makes them uncomfortable. I just empty myself out so what people see is a projection of their own needs.”

Lou retreated into his private world, finding refuge and solace in his relationship with Rachel and the group of addicts who centered around Ed Lister. Bob Jones, his only fan in the group, spent a lot of time with Lou in 1975, becoming Lou’s on-again, off-again drug supplier as well as playmate throughout the long, hard summer: “One of my biggest clients right away was Lou. I would get prescriptions from Lister, from Turtle, from Rita, from Marty, and I had a network of pharmacies I would go to. And another thing that was always difficult was getting syringes, I used to be the big syringe man. You had to go to the Upper West Side for syringes. You’d go to a drugstore and buy them by the box.”

Standard practice for the group was to shoot up first thing in the morning and then at some other point late in the day. The shots were so strong as to he considered lethal by conventional medical standards. A forged prescription of Desoxyn, for example, would consist of a bottle of one hundred yellow pills, of the highest (15-mg) potency. The ordinary recommended dosage, adjusted of course to meet the needs of the individual, was fifteen to twenty-five milligrams orally per day. The Lister amphetamine circle, on the other hand, would habitually use ten to twenty 15-mg pills at once and inject them directly into the bloodstream. These men were not messing about.

In order to inject the prescription pills, the amphetamine group prepared an intravenous solution. Essentially they put the pills in a pan on the stove and boiled them. The water would rapidly turn yellow from the drug released from the tablets, as much as three hundred milligrams of methamphetamine hydrochloride. The water could then be drawn into a syringe for injection into a vein.

The effects of such intense speed consumption were severe. “It was enough to take the top of your head off,” remarked Bob Jones. The shots explained Reed’s often temperamental states of being. “We never ate,” stated Bob Jones. “We were very, very wired. Everyone’s weight went right down. Lou weighed nothing. I lost forty pounds. And we never slept. The effect of having no REM, rapid eye movement sleep, was that we were deprived of dreams. So we would literally go for months without dreaming. The effect of this is that we would begin to have dreams in our waking state, which accounts for the paranoia and the delusionary style of the amphetamine addict.”

The first soaking of the pills produced a dark yellow in the water, representing a strong dose. When for one reason or another, the Lister group became low on pills—which happened a few times in the two years Reed was involved—they would pour more water on the used pills, in what they called a second soak. The result would be a faint yellowing of the water. Shooting this diluted mixture produced a weaker effect and a limited amphetamine high. It was enough, however, to hold them for a few hours while they went looking for more pills.

When amphetamine could not be found, members of the Lister group would convince themselves that putting sixty twice-used pills in a tube and boiling them up would result in some small amount of speed. However, the third soaking of pills failed to yellow the water. Deceiving themselves into believing that there was some speed in there, they would end up shooting water into their veins. Of course, impurities would go into their veins along with the water, which wasn’t such a good idea.

“What would happen,” Jones explained, “was that your temperature would go through the roof almost immediately, within five minutes; you would feel a strange aching in your body and the next thing you’d know is your temperature would be about one hundred and three. You’d be drenched in sweat and in terrible, terrible pain in all of your joints. Appalling pain. And you would take your clothes off because it was too painful to keep them on and lie down on the bed racked with shivers and diarrhea and agony, drenched in sweat. That was called a bone crusher. You would lie there with your knees drawn up to your chest and retch and cry out in pain. And this would go on for five or six hours. At the end of Lou’s involvement with the amphetamine scene, this happened three or four times in a studio. He’d get a bone crusher and couldn’t record. It was hopeless.”

Jones believed that the drug created the fodder for Lou’s songs, and the drug lifestyle was the ideal atmosphere for Lou’s work. After taking their shots, Reed and Jones would often sit around the former’s apartment. “There was nothing but drugs at Lou’s place,” Jones recalled. “There was never any eating. I guess in the course of time I gravitated towards Lou because I was interested in the way he spent his time in between shooting up, which was more interesting than what the rest of the group was doing. He was an international star at the time, it must have been hard to maintain his humility. Especially if you’re whacked out on drugs all the time. There would be acts of friendship, but Lou was very selfish. Lou probably had a few real relationships which would fulfill some kind of purpose. And I think in a funny sort of way the relationship he had with Rachel was a symbolic relationship. The relationship I had with him didn’t really exist except in the supplying him with drugs and with a pair of ears to listen to his speed rap about music and the drug world and crime. And someone who shared his interest in Warhol and was literate. There was a lot of strung-out, camp talk.”

The two devoted a lot of time to listening to music and discussing their ideas of what was interesting about a particular piece. Lou showed Jones, who was an intelligent sounding board, the new, speed-induced lyrics he was working on, and he would also play the songs in draft. Lou was constantly playing, trying out songs, playing little riffs, and working the words into the music. He was extremely prolific and experimented with all sorts of different styles. On one occasion he recorded a whole cassette tape of Bob Dylan parodies. Lou also incorporated many of his experiences on the speed scene into songs of his “criminal” period. “If you analyze them, all of those songs on Coney Island Baby and Rock and Roll Heart are about this little crowd and its comings and goings,” reported Jones. “Having an attitude was a big thing for Lou. Attitude was the sort of drug equivalent of what is called in the black world ‘signifying.’ Talking from the sides of your mouth.”

According to Jones, Lou’s social life outside this speed scene was limited. Although he was seeing some people in the music business, such as the singer Robert Palmer, his peculiar habits and long, erratic hours made it difficult for many friends to relate. He’d see guitarists, who’d come around and be moronic. He was very interested. They’d talk about music. He’d get interviewed and go into diatribes about lawyers. Outside of that, he’d see Rotten Rita, a real character from Warhol’s novel A, an account of twenty-four hours at the Factory with Lou talking about desoxyn. “Rita was about six foot two, a hundred and ninety pounds,” recalled Jones. “He lived under the elevated subway tracks in Queens in an absolutely terrible apartment. He had recently gotten out of jail in Bermuda, which he loved, and he had tapes of himself singing opera there. He was very wild, campy, and lonely. A very funny, potentially quite dangerous character, but at the same time quite sweet. You felt that he could tip a little bit and be capable of murder. And it was that side of him that was appealing to Lou. He was very much an outré camp figure who loved Callas; there was a lot of talk of Callas, there was a lot of playing of Callas albums, always opera, opera. He also became one of the main dealers.”

For Lou, one of the appealing aspects of such large doses of amphetamine was the effect it had on making the most horrible, chilling experiences, as well as horrible, chilling people, interesting. This accounted for his attraction, for example, to Lister and some of the other characters on the scene, like Rotten. For a writer and rock star, faced with a constant assault of painful experiences such as the chaos of touring, as well as the ever-present need for new material, the drug was an effective tool. According to Bob Jones, “There seems to be some kind of deprivation of the normal blocks against certain kinds of interest in the macabre. I became fascinated with the police, for example; it was a fascination Lou and I shared. There was a big police book that I bought at Barnes and Noble about gunshot wounds. And it showed in color people who had put shotguns in their mouths and pulled the trigger. It showed people cut up, shot, all kinds of wounds. You’d see their brains spilling out all over the place. And it was very much that attitude that Lou was involved in at the time and that I became involved in, and I think understood as he did. It was that kind of erotic fascination with death.”

Despite the drug’s seeming ability to open new vistas of creativity, in reality it was wearing him out. As his health deteriorated, his mental state and professional responsibilities suffered. Lester Bangs noted that “Lou’s sallow skin was almost as whitish yellow as his hair, his whole face and frame so transcendentally emaciated—he had indeed become a specter. His eyes were rusty, like two copper coins.”

A salesman in a record store in Cambridge, Massachusetts, described the people who were buying Lou Reed records: “You get like these twenty-eight-year-old straight divorcee types, asking for Transformer and The Velvet Underground, but the amazing thing is that suddenly there’s all these fourteen-year-olds, coming in all wide-eyed: ‘Hey, uh, do you have any Lou Reed records?’”

In retrospect, while rejecting his two most commercial RCA albums, Lou insisted that he made them in order to get the Velvet Underground albums back into print, claiming, “I kept going with Rock ’n’ Roll Animal because it did what it was supposed to do. It got MGM to repackage all those Velvet things, and it got the 1969 Live album out.”

That September, the double Velvet Underground album 1969 Live was released in the U.S. at the same time as several other Velvet Underground compilations were released in Europe. Patti Smith, on the verge of her entrance into the rock world as the high priestess of punk, but then still just a dog of a rock writer, reviewed the album in Creem, finding it oppressive and likable.

By releasing his commercial solo albums, Lou was able to service the audience who had come with him out of the sixties as well as the crazed and dazed younger fans who were now attending his concerts like hyenas in droves.

In retrospect, Lou was responsible for keeping the VU music alive by recording his albums and by pressing his former bandmates to release the music. His strategy was successful. Sterling Morrison, who had cut himself off from the music world, recalled with some annoyance that in early 1974 he began getting calls from Steve Sesnick: “And I thought, ‘What is this bullshit?’ Then Lou even called. Apparently his lawyer had told him to turn on the charm. They wanted me to sign the release for the 1969 Velvet Underground Live album. I did not want it released. There is a certain clean feeling that comes from not dealing with the people you’d have to, to collect royalties on anything like that. And I’d listened to the tapes and I thought, ‘Oh, man! I can’t see this selling ten copies!’ Musically I much preferred Live at Max’s Kansas City—it has much more energy. I said I was not going along with it. Then Steve Sesnick finally convinced me. I signed the release for a pittance because he told me he needed the money. I’m sure he was in cahoots with Lou in some strange way.”

Maureen Tucker got a phone call at work explaining that Lou wanted to put this album out, but that they all had to sign, giving their consent: “And we had to sign for like, two hundred dollars, or something. I said, ‘No, no, I won’t sign for two hundred dollars, what do you mean, two hundred dollars?’ Then some agent type was calling me at work like mad: ‘Well, how about three?’ So I said, ‘What, are you crazy? I broke my ass for seven years for three hundred dollars? Go to hell.’ Sterling and I held out for more. We said we’re not signing for anything less than fifteen hundred, which even then was stupid—fifteen hundred dollars, which we foolishly signed for.”

***

If Lou’s London period climaxed with recording Berlin, Lou’s Rock ’n’ Roll Animal period climaxed in his autumn–winter 1974 tour of the U.S. “He was very big in New York, New Jersey, Los Angeles, and part of the Midwest,” recalled the ever-faithful Barbara Falk. Rachel, listed as his “baby-sitter,” accompanied Lou on the tour. To dramatize his self- destructive motif, Lou kept “Heroin” in the tour repertoire, playing it for all it was worth. In a San Francisco column in Melody Maker of December 7, 1974, Todd Tolces described a “gory Guignol” before five thousand raving fans. Lou “pulled a hypodermic needle out of his boot … as the crowd erupted into cheers and calls for, ‘Kill, kill!’ he tied off with the microphone cord, bringing up his vein. As the writer ran for the gentlemen’s toilet, Lou handed the syringe to a howling fan.”

No one could be certain what had really happened, but the image lingered on and added fuel to the talk that these were Reed’s final shows, that he would be unlikely to live beyond Christmas. For even if he wasn’t. actually shooting onstage, he was shooting up somewhere, and the drugs and lifestyle were killing him.

In the mid-seventies, Lou was hitting the zeitgeist smack on the nose day after day. Although at home Lou was still the sentimental little boy who liked nothing more than to play with his dog, onstage he appeared as ugly, violent, vicious, and stupid as the confused times seemed to call for. “The Stanley Theater was the perfect setting for rock’s king of decadence—Lou Reed—and he knocked them dead last night,” wrote Peter Bishop in Andy Warhol’s hometown, Pittsburgh. “Once he got onstage, the crowd already standing on the seats applauding, he proved himself a star, embellishing the glitter-language lyrics with a choreographic blend of go-go, jitterbug, free-form, and street-fighting moves that threatened to shake the painted-on jeans from his scrawny hips. And how the audience loved it when he made the raunchy lyrics of ‘Walk on the Wild Side’ even raunchier. This song and Reed himself are definite vestiges of the decadent movement of the late 1800s, and how Oscar Wilde and Aubrey Beardsley would have loved to hear and illustrate that song. He gives you more than your money’s worth of music and show; he’s what rock and roll is all about.”

In Cleveland, RCA got September 13 proclaimed Lou Reed Day. A couple of weeks later RCA proclaimed Lou Reed Impact Day in New York, where Lou played shows at the Felt Forum.

Lou was not often able to receive backstage guests after his shows because he was more often than not so profoundly moved by the emotional impact of the music and audience that Barbara would find him alone in his dressing room, unable to face anyone but her, sobbing uncontrollably. As Barbara described it:

“He’d be wrung out, drenched, shaking, and sometimes crying from sheer release of all this pent-up emotion. Especially if it was a good audience. Or if there was a really bad audience and he’d be upset that there wasn’t anybody there. It was a physical and emotional release. After a while I would leave him alone to help pack up, and then he wouldn’t want to leave. And he’d talk about it—he’d say, ‘Did you see these moves or that step?’ I think he fancied himself a good dancer, but he was terrible. He was best with just the cigarette.

“Other stars admired him greatly. He never came out and said it, but I think he was touched when they found him pretty nifty. I’ll never forget Mick Jagger crouching down behind the amps at the Felt Forum so he didn’t detract from Lou’s performance. I would bring him little glasses of champagne. Mick wanted to come right back into the dressing room and tell him how fabulous he was.

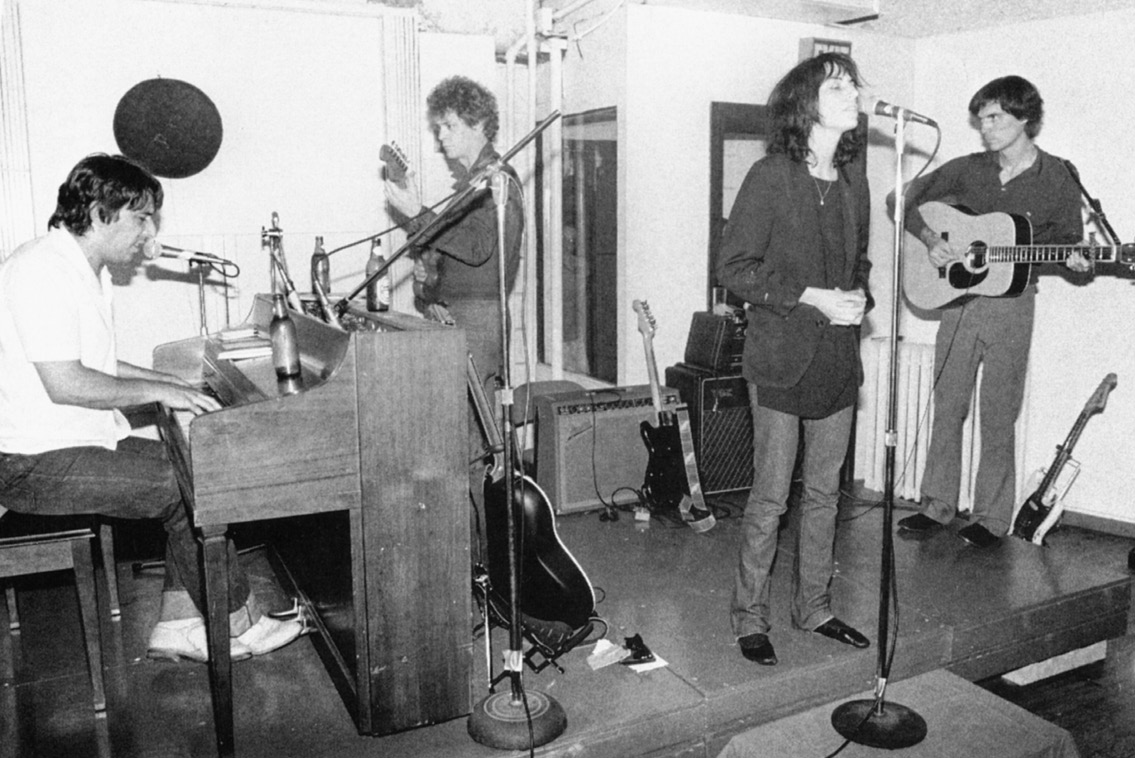

Mirror, mirror on the wall … Lou Reed gazes at his alter ego, 1975. (Gerard Malanga)

“At the end of the year, he was more erratic. Dennis suggested that he go to his own doctor. Lou looked up to him so much that he trotted off. I can’t imagine his doing this for anyone else. The doctor reported that Lou had … slightly elevated cholesterol. Ha! Lou never let Dennis forget this. His idea of a real doctor, of course, was the notorious Dr. Feelgood. Sometimes he’d be waiting on that doctor’s step at six a.m.” By the end of 1974, many sixties rock icons had moved into the mainstream. On December 13, for instance, former Beatle George Harrison had lunch with President Ford in the White House. Lou determined to defuse any attempt on the part of the record company or the critics to classify Lou Reed in the middle of the road.

***

In January 1975, he went into a New York studio with a stripped-down band and recorded the seeds of the raunchy Coney Island Baby—“Kicks,” “Coney Island Baby,” “She’s My Best Friend,” and “Downtown Dirt”—in four days. Dennis Katz told Lou flatly there was no way this music could be released. The songs were too raw, too negative. “Dirt,” for one was an obvious and brutal put-down of Katz. As a result, Coney Island Baby was temporarily shelved and Katz sent Lou back on the road, telling him he was broke. It looked like an insensitive move. Sending the unstable, overloaded Reed on an international tour was likely to push him over an edge he had been teetering on all year. Behind him lay a crumbling relationship with Dennis Katz, and the slithering Rock-’n’-Roll Animal himself, whose skin he was painfully shedding. Reed was desperate to find a new image that would free him from the prison of glam rock. But, for the time being, the only reality that Lou could hold on to apart from his music was Rachel.

Accompanied by Rachel, the loyal Falk, and a surprise addition to the band, Doug Yule, Reed launched this tour in Italy. The country, unbeknown to Lou, was in political turmoil. On February 13, a Dada-influenced gang called Masters of Creative Situations disrupted his first concert in Milan. As Falk explained, “These riots had nothing to do with Lou; they just chose our arena as their battle site, because there were so many people there. The fascists and the communists were trying to influence the elections, so they threw tear gas at the stage. The riot police were all over the place with big shields.” Throwing bolts and screwdrivers at the band, the rioters leaped onstage and denounced Reed as a “decadent dirty Jew.” Lou left the stage in tears. He refused to proceed.

Barbara canceled the next show in Bologna and took him to Switzerland. Once he was in a neutral country, Lou demanded that somebody from the Katz team fly over to consult with him. Both Katz brothers declined the invitation. However, the bushy-eyed manager of David Bowie, Tony DeFries, who had been trying to manage Lou since 1972, jumped on a plane and went in their stead. “We were holed up in this very modern hotel in Switzerland,” Falk recalled, “and Lou called DeFries. Lou said Dennis should have been there, Daddy should have held my hand. Dennis was furious when DeFries came to Switzerland, that Lou would even consider talking to DeFries.”

However, when DeFries arrived in Switzerland, Lou holed up in his Zurich cocoon hotel suite and refused even to have a cup of coffee with Tony in the lobby. The unfazed DeFries flew back to New York without so much as clapping eyes on Reed. He’d made his point, and both Reed and Katz knew that he was serious.

From then on, the tour grew rapidly worse. The next concert was also aborted, the promoter claiming Reed had a nervous breakdown. Another riot ensued. In France, a fan jumped onstage and pulled a knife. In England, a fan bit him on the bum. But the final straw was when Dennis suddenly yanked Barbara Falk off the tour, replacing her with an antique car mechanic named Alec. Lou went ballistic. First, he smashed up Coca-Cola bottles and stuffed the shards of glass in the hapless road manager’s pockets, and Alec cut his hand. Then, taking a page from Elvis Presley’s tour guide, Lou smashed up an RCA car that did not meet his requirements. Barbara Falk returned:

“Things were starting to go sour. Lou was having convulsions from the speed. Speed is insidious, and the personality changes are radical. Lou would go from being a nice Jewish boy from Long Island to a paranoid maniac. He would have hallucinations about intricate Machiavellian plots working against him. That’s why he was always suing—when in doubt, litigate. Other occasions merited more violence. He took his reviews very seriously and sometimes wanted to kill the writers, no matter how much they adored him. Fortunately a member of his family was around to help me.” His favorite cousin, Judy, who was traveling in Europe, joined him for a few shows, helping Lou through the ritual of preparing for his nightly performance. “He listened to her because he was going through a difficult time,” said Barbara. “She said he’d listen to a strong woman. I remember shoving Valiums down him. Like all drug freaks, he felt he had complete control over the drug. In my experience, no matter how intelligent or visionary a person might be in other parts of his life, no matter how intimate his knowledge of the drug’s effects, he still thinks he’s stronger. And Lou had a much larger ego than your average speed freak.”

Barbara had put the fear of God into the band about carrying drugs since they were bound to be strip-searched as they crossed borders daily. But “Europe, of course, is famous for easy prescriptions, so Lou would go to a different speed doctor in every country,” she recalled. “He truly believed in it! He was forever proselytizing, trying to get me to take some. On tour he’d actually go to medical bookstores, he’d literally carry around written justification for amphetamine. Not only that, but he knew how to pronounce it correctly, in every language.”

Despite his protestations, it was not a healthy life. He often stayed up for days at a time. In Europe that winter, as a result of clinical fatigue, he collapsed in convulsions on several occasions.

***

At the beginning of March 1975, Lou returned to the U.S. in time for the release of Lou Reed Live, a second album culled from the December 1973 shows that produced Rock ’n’ Roll Animal. Lou Reed Live was yet another commercial success, reaching No. 62 on the LP charts, where it hovered for several months. “Satellite of Love,” “Sad Song,” and “Vicious” placed him in the mainstream of rock between Elton John and the Rolling Stones. On the live album, Lou insisted that the producers keep the clear hollow ring of a youth’s voice screaming out from the bleachers, “Lou Reed sucks!” at the very end of the second side.

The trilogy of Rock ’n’ Roll Animal, Sally Can’t Dance, and Lou Reed Live vaulted Lou from the hesitant commercial start of the early seventies to the rock mountaintop. His distinct following of the most mentally disturbed people in each country gave him a higher profile than he might otherwise have had. Lou Reed fans were loud, nasty, and exhibitionistic. “During the U.S. tour, mutual hostility rose in waves during some shows. The standard audience expression,” according to Janet Macoska in the Cleveland Commuter, “was one of stunned boredom, hands barely holding up nodding heads … And Lou, half the time, had no idea what he was supposed to be singing.” But by the time he reached Detroit, then home turf of Lester Bangs, he had once again managed to focus his rage; Lester thought the show was superb.

At this midway point in the decade, Lou’s famed interview slugfest with the writer Lester Bangs in Creem magazine reached its climax. “I always thought when Lou was being interviewed by Lester Bangs was the peak of his career,” said the cartoonist John Holmstrom. “Lou hated Lester. They really hated each other. Lester had a love–hate thing. Lou just had the hate.” “Bangs attempted to place rock within a cultural framework, pointing out its similarities to everything from Dada to Jack Kerouac,” wrote critic Kyle Tucker. “For a critic like Bangs, Andy Warhol was as much of an aesthetic signpost as the Beatles; an understanding of Lou Reed, the Velvet Underground founder, was impossible without discussing Brecht’s alienation effect.”

Ever since the Velvet Underground played San Diego in 1968, Bangs had set himself up as the conscience of Lou Reed and the Velvet Underground. After celebrating the Velvets during their last two years, he had remained true to them through the first half of the seventies, writing obsessively about their influence and keeping tabs on the activities of Cale, Nico, and Reed. But when he met Reed during the U.S. tour, Bangs wrote, “Lou Reed is a completely depraved pervert and pathetic death dwarf and everything else you want to think he is.”

“See, this to me is what rock journalists do, they rip off, make fun of musicians … y’know, and sell to morons,” responded Reed in an interview. “Written by morons for morons … The best way to get anything publicized is to tell Lester, ‘Please don’t print that.’ And he’ll print it. The very best way is to let him overhear something accidently on purpose.” Asked, “Did you read the story Lester Bangs did on you?” Lou replied, “Oh, yeah. We both worked on it very hard. He thinks he won the last time, but that was only because I let him think that. He’s the best PR agent I have. The worse things he writes about me, the better it is. If he ever started writing good things about me … it would be like the kiss of death. I mean, everyone has turned the old Velvet thing into much more than it ever was.”

From then on, Reed’s American concerts received critical raves. “Both Mr. Reed’s concerts and his records have been up-and-down affairs over the last couple of years, and in that context Saturday night at the Felt Forum must be counted as a success,” wrote John Rockwell in the New York Times on April 28. “His singing was as tuneless as ever, but the phrasing remains gripping, and his backing quartet strikes a nice balance between professionalism and the out-of-tune raunch of his Warhol days. But in a large measure the risk has gone. Mr. Reed has made himself into a rock star—a strange, weird rock star, to be sure, but a rock star nonetheless. Still, in the old days he gave promise of something more daring, if more lonely.”

As the graph of his record sales rose, however, Lou’s emotional state plummeted. The break with Bettye, the rejection of Berlin, the struggle with the Katz brothers, the riot-torn tour, and the success of Lou Reed Live, another album he professed to loathe, reduced him to a fried geek. Meanwhile, the more he stumbled, the less capable he became of performing, the more audiences goaded him to fall. Pinned by the spotlight to the stage, he began to portray himself as rock’s next sacrificial victim. He claimed that Bowie had told him “that ‘Rock ’n’ Roll Suicide’ (on Ziggy Stardust) was written for me.” Asked how it felt to be voted second only to Keith Richards in a Who Will be the Next Rock ’n’ Roll Casualty in a recent magazine poll, Lou exclaimed, “Oh really, that’s fabulous. It’s a real honor to be voted after Keith. He’s a real rock ’n’ roll star.”

Great rock stars often have the ability to respond to the very worst situation by performing at the top of their game. Lou was one such animal. With everything against him by the time he returned to New York, Reed was delivering a gripping set. “He was such a romantic figure at that point,” said Bob Jones. “He was as good as you could be. He was very much a Rimbaud figure.”

“By far his greatest work was composed when he was on drugs,” pointed out Glenn O’Brien. “But who is successful using amphetamine over a long period of time?”

In the spring of 1975, after three years of relentless, amphetamine-fueled touring behind his most commercially successful albums, Reed faced a new contractual demand from his product- and profit-hungry record company, RCA: he had to deliver a new studio album. The “product” Lou came up with this time was way beyond anything any of his fans could have contemplated in their wildest expectations. A screeching cacophony of feedback and electronic noise that lasted for sixty-four minutes, it was called Metal Machine Music.

“As soon as he came walking into my office, I could see this guy was not too well connected with reality,” recalled an RCA representative to whom the lot fell to steer Reed through this production. “If he was a person walking in off the street with this shit, I woulda threw him out. But I hadda handle him with kid gloves, because he was an artist in whom the company had a long-term commitment. He’s not my artist, I couldn’t get his hackles up, I couldn’t tell him it was just a buncha shit.”

The only thing the RCA executives knew about Lou was that Lou’s last three albums—Sally Can’t Dance, Rock ’n’ Roll Animal, and Lou Reed Live—had been moneymakers. The company had high hopes that he would deliver another. Consequently, in a series of meetings about Metal Machine Music, they let Lou walk all over them. After talking the RCA people into presenting this highly unusual product, Lou told friends he had had to run to the men’s room to explode with adolescent laughter. “I told him it was a ‘violent assault on the senses,’” continued the RCA executive. “Jesus Christ, it was fuckin’ torture music! There was a few interesting cadences, but he was ready to read anything into anything I said. I led him to believe it was not too bad a work, because I couldn’t commit myself. I said, ‘I’m gonna put it out on the Red Seal label,’ and then I gave him a lot of classical records in the hope that he’d write better stuff next time.”

Everybody at the company was horrified by Lou’s new weirdness. One marketing executive, Frank O’Donnell, recalled, “About twenty of us were seated around a vast mahogany conference table for a monthly new-release album meeting. The A-and-R representative at the meeting put on the tape and the room was filled with this bizarre noise. Everyone was looking at everyone else; people were saying, ‘What the hell is that?’ Somebody voiced that question and the answer came back, ‘That’s Lou Reed’s new album, Metal Machine Music. His contract says we’ve got to put it out.’

“One day a middle-aged, very conservatively dressed and coiffed executive secretary asked me what I knew about ‘this recording artist Lou Reed.’ I told her, ‘Well, I know he was involved with Andy Warhol and the Velvet Underground. One of his songs is called “Heroin,” so I believe he has a pretty big following in the drug culture. He’s kind of in the David Bowie groove—you know, eye makeup and lipstick and all that, so the homosexuals like him. His brand of rock and roll is pretty wild … why do you ask?’ The lady looked side to side, warily. Then, sotto voce, she said, ‘He’s my nephew. But if you don’t tell, I won’t tell.’”

The company had wanted to issue Metal Machine Music on the Red Seal classical label, but Lou demurred, arguing that the venue was pretentious. Instead, they disguised the platter within a record sleeve showing Lou looking extracool onstage, clearly suggesting that this was his Blonde on Blonde. Included on the jacket was a list of the equipment putatively utilized in the recording, along with a bunch of supposed scientific symbols that Lou had copied out of a stereo magazine. “I made up the equipment on the back of the album,” he later said, laughing hysterically. “It’s all bullshit.” After much gnashing of teeth and pulling of hair on the part of RCA’s top brass, the album was released in July 1975. Those not prepared for what lurked beneath the cover of Metal Machine Music were in for a big surprise. According to Lou, “They were supposed to put out a disclaimer—“Warning: no vocals. Best cut: none. Sounds like: static on a car radio’”—but did not. The double album, subtitled “An Electronic Instrumental Composition,” was mixed so that each side was exactly 16:01 in length—except that side four was pressed so the final groove would stick, repeating grating static screeches over and over until the needle was rapidly removed from the record by the hapless client.

Reed presented the album as a grand artistic statement, claiming that he had spent six years composing it, weaving classical and poetic themes into the noise. If one listened attentively, he promised, one could hear a number of classical themes making their way in and out of the feedback fury. “That record was the closest I’ve ever come to perfection,” he stated. “It’s the only record I know that attacks the listener. Even when it gets to the end of the last side, it still won’t stop. You have to get up and remove it yourself. It’s impossible to even think when the thing is on. It destroys you. You can’t complete a thought. You can’t even comprehend what it’s doing to you. You’re literally driven to take the miserable thing off. You can’t control that record.”

“I could take Hendrix,” he told Lester Bangs. “Hendrix was one of the greatest guitar players, but I was better. If people don’t realize how much fun it is listening to Metal Machine Music, let ’em go smoke their fucking marijuana, which is just bad acid anyway, and we’ve already been through that and forgotten it. I don’t make records for fucking flower children.”

Asked Lester, “Speaking of fucking, Lou—do you ever fuck to Metal Machine Music?” “I never fuck,” Lou shot back. “I haven’t had it up in so long I can’t remember when the last time was.” On another occasion when a fellow musician offered Lou access to his girlfriend, Reed claimed, “I’m a musician, man. I haven’t gotten it up in seventeen years.”

For the most part, the press’s and the public’s reaction to Metal Machine Music was a combination of outrage and contempt. Rolling Stone voted it the worst album of the year. Even John Rockwell, who had been a champion of Reed’s since Berlin, delicately questioned its release. “One would like to see rock stars take the risk to stretch their art in ways that might jeopardize the affection of their fans,” he wrote. “But one can’t help fearing that in this instance, Mr. Reed may have gone farther than his audience will willingly follow.” Lou, for his part, was of the opinion that Metal Machine Music would be the perfect sound track for the cult horror flick The Texas Chainsaw Massacre. And he may well have been right.

(NB: As an aficionado of movies, Lou listed as one of his favorite films of all time The Ruling Class, starring Peter O’Toole as a man who thinks he is Jesus Christ. Any serious fan of Reed’s should make a point of seeing this film as an excellent example of Reed’s self-image.)

Lou anticipated a strong reaction from his fans. He insisted, “I put out Metal Machine Music precisely to put a stop to all of it. It was a giant fuck-you. I wanted to clear the air and get rid of all those fucking assholes who show up at the show and yell ‘Vicious’ and ‘Walk on the Wild Side.’ It wasn’t ill-advised at all. It did what it was supposed to do. I really believed in it also. That could be ill-advised, I suppose, but I just think it’s one of the most remarkable pieces of music ever done by anybody, anywhere. In time, it will prove itself.”

To anyone who would listen he said, “Metal Machine Music is probably one of the best things I ever did, and I’ve been thinking about doing it ever since I’ve been listening to La Monte Young” (whose name Lou misspelled on the back of the album). “That album should have sold for $79.99,” he snapped to another astonished scribe. “If they think it’s a rip-off, yeah, and I’ll rip them off some more. I’m not gonna apologize to anybody! They should be grateful I put that fucking thing out, and if they don’t like it, they can go eat rat shit. I make records for me.”

The record, which would soon come to be seen as the ultimate conceptual punk album and the progenitor of New York punk rock, harkened back to the work of La Monte Young and the Velvet Underground’s experimental track “Loop” (1966). “The key word was “control,”” Lou concluded in Metal Machine Music’s liner notes.

In a conscious effort to present Metal Machine Music as a composition, Reed not only left the individual sides untitled, but offered a parody of classical liner notes. His first piece of published prose since his essay “No One Waved Goodbye,” the Metal Machine Music “Notation” was a combination of arrogance, bluster, and inadvertent confessional. The writing was punk. Its subject shifted from Reed’s complaints about the tedium of most heavy metal, through the symmetrical genius of his creation, to puns on his album titles, to insights about the gap between drug “professionals” and “those for whom the needle is no more than a toothbrush.” It noted, “No one I know has listened to it all the way through including myself … I love and adore it. I’m sorry, but not especially, if it turns you off … Most of you won’t like this, and I don’t blame you at all. It’s not meant for you.”

In the end, almost one hundred thousand copies sold. “The classical reviews were fabulous,” Lou reported.

In August, leaving his critics and fans with an unpleasant ringing in their ears, Reed went on another grueling tour of Japan and Australia. Every tour has a theme. This one was called the Get Down with Your Bad Self Tour. “In Japan, they greeted me by blaring the fucking thing [Metal Machine Music] at top volume in the airport,” he claimed or hallucinated. Nobody in his entourage had any memory of this incident.

What they do remember is a press conference at the airport immediately following the grueling thirty-hour flight from New York to Sydney at which Lou rivaled the mid-sixties Dylan in repartee:

PRESS: It says in this press release that you lie to the press. Is that true?

LOU: No.

PRESS: Would you describe yourself as a decadent person?

LOU: No.

PRESS: Well then, what?

LOU: Average.

PRESS: Is your antisocial posture part of your show-business attitude?

LOU: Antisocial?

PRESS: Well, you seem very withdrawn. Do you like meeting people?

LOU: Some.

PRESS: Do you like talking to us?

LOU: I don’t know you.

PRESS: Would it be correct to call your music gutter rock?

LOU: Oh, yeah.

Joining the tour on bass was Doug Yule, back with Lou since the Sally Can’t Dance sessions. “When we traveled as the VU, we traveled as a group,” Doug recalled. “But here he and Rachel traveled together—they were like the VIPs—and everybody else traveled behind. It was nice, it was fun. He was a little more mercurial.”

In fact, much distance had come between Reed and the rest of his entourage, including the ever-present Barbara Falk. Unfortunately, this was not an altogether healthy change, resulting in one of the few times Lou was incapable of overcoming his drug-induced exhaustion to make it to a show. “I once saw him consume fifteen straight tequilas—doubles!—in a drinking contest with a drummer in New Zealand,” recalled Barbara. “And then he walked away.”

“In New Zealand he couldn’t perform,” said Doug Yule. “So there was an announcement that Lou wasn’t going to play but the band was going to play. Anyone who wanted their money back could have their money back. We went out and played and I sang. The audience liked it a lot. But it was not an attempt [as had been reported] to present it as if I were Lou, nor were the people told I was Lou.”

Meanwhile, in a series of frantic phone calls between New Zealand and New York, Reed was given the impression that Katz was rapidly moving to take control of his finances and tie up his recordings. The first casualty of this escalating battle was Barbara Falk. Exhausted after three years of baby-sitting Lou on twenty-four-hours-a-day call, she left the tour after Lou accused her one too many times of being in cahoots with Katz to cheat him. “Our last tour of Australia is what did it,” stated Barbara Falk. “I was exhausted—this was mid-’75, and we’d been pushing very hard, all over the U.S. and Europe, behind Sally Can’t Dance. My routine of being the bookkeeper, the bouncer, and big mama wasn’t covering the gaps. It all really started with Metal Machine Music, an album I didn’t particularly like. I didn’t tell him this, but I didn’t praise it to the skies, either. Before this I was his biggest fan and strongest support, always convincing him that he was the cult musical figure of the century to be cherished and protected. But as I said, the instant the stroking stopped—and he noticed instantly that I wasn’t carrying around the reviews of the album and passing them out to strangers on the street—he got progressively more nasty. It was awful at the end, and I had to abstain and just leave. I got on a plane and got out of Australia.”

Extremely agitated by thoughts of betrayal, Lou was unable to go on with the tour. Returning to New York, he found himself, as it were, back at square one. While he had been touring, Dennis Katz had marshaled his chess pieces and presented Reed with what amounted to a checkmate. According to Reed, Dennis Katz’s office had cut off his support payments. He discovered that he no longer had an apartment or money in the bank, then was informed that he was $600,000 in debt to his record company. Furthermore, RCA did not intend to proceed with his next album as planned.

Lou believed that the only way to face a storm was to drive right through its center at breakneck speed. Approaching RCA president Ken Glancy, Lou talked him into supporting him long enough to come up with a commercial album. Glancy, who knew Reed personally and believed in him in the same way that Katz once had, agreed to put him up in a suite at the Gramercy Park Hotel, an establishment that had seen better days but now exuded a louche charm as home for traveling rock bands and European tourists.

Lou was comfortable there. RCA picked up his room and restaurant bills and gave him $15 per day in cash. The hotel’s restaurant had the air of a department store and served bland food, but the bar pulsed with cute groupies waiting for the appearance of any rock star. While Lou was there, Dylan’s entourage was using it as a base for their Rolling Thunder tour and invited Lou to join them. He had to decline the offer.

The pecuniary difficulties strengthened the bond between Lou and Rachel. According to Lou, Rachel weathered hard times because she was “a street kid and very tough underneath it all.” They also had a lot of fun together. Lou never tired of shocking people. One day a maid came into their suite unaware that they, Mr. and Mrs. Reed, were in bed. When she saw “Mrs. Reed” lying uncovered and naked, displaying an unexpected appendage, she gave a little cry and fled. Lou, who was awake and witnessed her shock, was in stitches for days over the sighting.

The sparse setup at the hotel helped Lou focus singularly on Coney Island Baby. In between writing songs and recording, he met with his lawyers to discuss his three lawsuits against the Katz brothers. For entertainment, he listened to tapes of the comedian Richard Pryor and held court. In between Lou’s raps, Rachel and assorted visitors whiled away the hours playing Monopoly. During his stay at the hotel, a friend brought a grateful Lou a copy of the manuscript of Lou’s book of poems, All the Pretty People, that he wanted to get published. He had mislaid the collection during his recent move.

***

Coney Island Baby was first recorded from October 18 to 25. RCA was very hopeful. “They said, you can do anything you want so long as it’s not Metal Machine Music,” Lou sneered. He entered the studio with Steve Katz again as coproducer and a full complement of new musicians.

It wasn’t long, however, before Steve found Lou impossible to work with. And, stonewalled by Reed’s amphetamine abuse, he quit. “There was no other way. Each day a new head trip. Finally I said to him, right in front of all the musicians who’d gone through this, ‘I give up! If you’re gonna play these games, I know you’re gonna outwit me. I’m just your producer. I acknowledge that you’re much smarter than I am—there’s no point in playing these games.’” Asked “What’s better than sex?” that week, Lou replied, “Facts!”

Steve recalled, “The drugs had taken over and things were completely crazy. I felt that Lou was, at the time, out of his mind. So I had to stop the sessions. I had someone in authority at RCA come to the studio and verify that I could not make an album with the artist—that was that.”

During the recording of the album, Lou was so enmeshed in lawsuits with the Katz brothers it is amazing that he was able to concentrate on his work as well as he did. He thrived on conflict.

When Lester Bangs asked, “What do you think that the sense of guilt manifested in most of your songs has to do with being Jewish?” Lou snapped, “I don’t know anyone Jewish.” But he went out of his way to make anti-Semitic remarks about Dennis Katz, telling one astonished interviewer, “I’ve got that kike by the balls. If you ever wondered why they have noses like pigs, now you know. They’re pigs. Whaddaya expect?” The lyrics to “Dirt” refer to someone who said shit tasted good for money. “I was specifically referring to my manager-lawyer at the time,” Reed explained.

Reed and Katz sued each other for breach of contract. “There was a suit and a countersuit,” Falk explained. “And by then, according to Dennis, it was black-and-white—Lou was a jerk and Lou was a … and don’t even mention his name. This artiste he had extolled. And then Lou called me. He even asked me to manage him. I said, ‘You don’t want me to manage you.’ I said, ‘Lou, I will always tell the truth. I know that you feel hard done by, and in some ways you were, but I don’t know if it was illegal. There may be things I don’t know about. If you want to know anything, I’ll tell you.’ And I had a meeting with his lawyer at the time. And he was in my face with his finger. and blah blah blah. I said, ‘I’ll be glad to tell you anything you want to know.’ But he was trying to say that Lou was drugged-out half the time and didn’t know what he was signing away and he was taken advantage of. But I said Lou was very bright and it was my impression that he was aware of what was going on.”

Several years later, in an attempt to redeem himself before the eyes of the public, Lou published in Punk magazine the defendants’ memorandum of laws concerning his suit with Steve Katz and Anxiety Productions. It read in part:

The relationship between an artist and his chosen producer is an intimate employer–employee relationship. The shocking bitterness and personal animosity with which Katz, the employee, regards Reed, the employer, is written in bold letters throughout Katz’s Affidavit. For example, he calls Reed:

—confused, self-destructive and immersed in the drug culture (Katz Aff. p. 16)

—an irresponsible drug-induced musical meanderer (p. 17)

—financially irresponsible (p. 20)

Reed was convinced serious errors had been made. “I went over things with a microscope and found it so interesting. I’ve got three lawsuits going,” he attested. “Everything from misrepresentation to fraud and back again. The management I had then had me in a cocoon in paranoia: when you’re ripping somebody off that much, you don’t want them outside talking to people.”

“I was a bit erratic before,” he admitted. “You get tired of fighting with people sometimes. And to avoid going through all of that, I mastered the art of recording known as ‘capture the spontaneous moment and leave it at that.’ Coney Island Baby is like that. You go into the studio with zero, write it on the spot, and make the lyrics up as the tape’s running and that’s it. What I wanna get on my records, since everyone else is so slick and dull, is that moment.”

In October at the club of the moment, Ashley’s, on Lower Fifth Avenue, Lou met the man who would help bring Coney Island Baby to fruition. Godfrey Diamond, a talented young engineer in his early twenties, would become his next producer. Diamond admitted that he “really wasn’t a huge fan of his up to that point. I guess I was too young. But I really loved the banana album and Transformer. ‘Satellite of Love’ was a work of art.” Diamond returned to the Gramercy Park Hotel with Reed that night to listen to his new songs: “One thing that really impressed me is that he always goes for the tough edge, the risky stuff. I thought he was a real warrior, with such courage.”

Around five o’clock on the morning of the day Reed and Godfrey finished Coney Island Baby, Lou took Diamond over to Danny Fields’s apartment for an immediate judgment. Fields had become the critic and authority on the downtown music scene, and Lou regularly sought his opinion. As soon as they got there, they plugged in the record and took a seat in Fields’s living room. To Diamond’s dismay Danny pulled out a newspaper and appeared to be engrossed in it. Lou whispered to him that Danny always did this so you could not see the expression on his face while he listened to your record. After a tense (for Diamond) forty-five minutes, Fields snapped shut his paper and declared, “Great! Not one bad song.” They stayed there until 8 a.m. when Diamond had to go to work.

All that remained was for Mick Rock to do a photo session for the cover, and Lou had completed one of his finer solo recordings. RCA was as pleased with the results as he was.

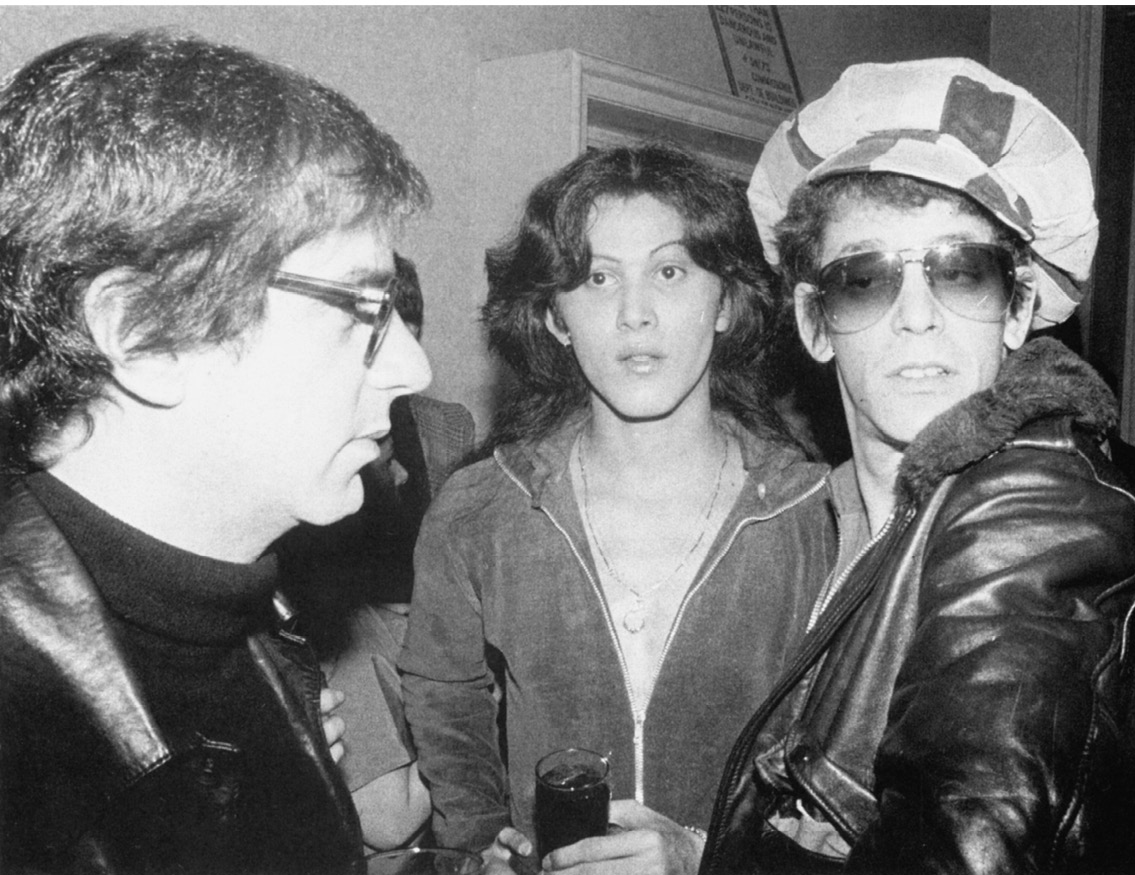

Danny Fields with Lou and Rachel in New York, 1976. (Bob Gruen)

As soon as Lou completed Coney Island Baby, like a musician on tour well oiled after playing six weeks of dates, he went straight into another project equally dear to his heart. Andy Warhol, who was in 1975 at the height of his game once again, had just published his best book, The Philosophy of Andy Warhol. It was full of advice about how to tackle the very problems that most beset Lou. Inscribing a photocopy of the proofs to his old disciple with “Honey, from Andy,” Warhol seduced the prolific Reed into writing an album of songs based on the book for a projected Broadway show. It was a dry run of sorts for Songs for Drella, Reed’s posthumous homage to Warhol, which he would release in 1990. According to Bob Jones, “Lou used to talk at great length about Andy and how Andy was somehow the ultimate figure of idealization. I remember Lou telling me that Andy was the strongest man that he’d ever met—physically. That he could leap over buildings in a single bound. He was absolutely crazed about it. He said Andy had arms like steel. For Lou, Andy was also, I remember him saying, like Aristotle. Like Aristotle and Leonardo and Andy. I remember a conversation in which I said surely you don’t think Andy is as great as Leonardo. And Lou said, ‘Absolutely, much greater than Leonardo, much more interesting and smarter.’”

“I see him all the time,” Lou explained. “I’ve talked to him more than probably anyone I’ve ever talked to. He showed me how to save a lot of time.”

Jones went to the Factory with Lou once when they were both speeding: “I remember sitting on the table and having Bob Colacello making fun of Lou in a catty way. And Fred Hughes coming around and Lou disappearing into the back with Andy. Coney Island Baby had just come out and he was bringing Andy a copy.

“Andy was a little bothered by him. They had had hard times together, had difficulties and arguments. Lou was pretending a greater closeness to Andy than those who were around Andy had so that Lou’s attitude was, “I’m closer to Andy than you would ever be, Bob or Fred.” And actually Bob and Fred resented that and were condescending about Lou. But Andy wanted to keep his distance from Lou.”

Lou wrote his adaptation of Andy Warhol’s Philosophy overnight. “I was so surprised,” Warhol admitted. “He just came over the next day and had it all done.” “I played the songs for Andy,” Lou explained. “He was fascinated but horrified. I think they kind of scared him.”

***

In many ways, in his Rock ’n’ Roll Animal incarnation Lou was more completely the controlled self he wanted to be. During this period he reached his artistic maturity and was able to best collaborate with the differing selves he had picked up along the way. “Realism was the key, the records were letters, real letters from me to certain other people who had and still have basically no music, be it verbal or instrumental, to listen to,” he wrote in the liner notes to Metal Machine Music.

Describing heavy-metal music, he wrote it was “diffuse, obtuse, weak, boring and ultimately an embarrassment.” Responding to criticism about ethnic or racial slurs in his lyrics (he actually backed off from including “I Wanna Be Black” in the collection Sally Can’t Dance for fear of a backlash), Reed snapped at one trembling interviewer, “What’s wrong with cheap, dirty jokes? Fuck you, I never said I was tasteful. I am not tasteful.”

***

At the beginning of 1976, Lou made a definitive break from his recent past. He no longer relied upon Katz to steer him through the twisted path to international superstardom. He no longer looked to Warhol for approbation and permission to be Lou Reed. Now, instead of hiring a new manager for the seventies, as so many of his peers were doing, he elected instead to hire a booking agent to oversee his increasingly profitable touring career, one Johnny Podell. Wrote Reed chronicler Peter Doggett: “Fast-talking, all skin and bone and at that time in his life very fond of cocaine, Podell was a man of the streets, and Lou adopted him as the latest in a succession of bosom buddies–comminglers, just as he had done Katz, Heller, Sesnick, and Warhol before him. At Ashley’s, the music biz bar and restaurant on Fifth Avenue at 13th Street where Lou and Podell hung out with their friends, the regulars quipped that their business relationship was ‘a marriage made in the emergency ward!’”

Having, for all intents and purposes, rid himself of Dennis Katz—although their lawsuits would rage on for two years—Lou, in the enthusiasm of the moment, proceeded to talk up John Podell to the press. “I’m not unmanageable,” he said. “Not true. It’s just that I’ve never hit on the right people before. John Podell, my new man, is great. He got an MA in business psychology at twenty-one, and he’s as good at practice as he is at theory. He doesn’t handle my money, I’ve got all new people to do that, but he gets all the rest together. It’s a whole new show now on that front. Anyone who was connected with me on a business level before is out. My accountants, lawyers, record-company manager, his brother quote producer—all out. With Johnny you’ve got a tiger by the tail. He’s ready to go. The product is there. I like that. I’m the product and I call myself the product. Much better than being called an artist—that means they’re fucking you, they think you don’t know from shit. This time I’m doing it for real, because it seems that’s what’s supposed to happen.”

Around the beginning of 1976, Lou’s new status was made evident when he moved with Rachel and the new addition to their family, a dachshund named the Baron, into a furnished Upper East Side apartment building on 52nd Street a few doors down from the reclusive Greta Garbo. Although Lou did not make much of his famous neighbour, choosing to play the connection down, all his so-called two-bit friends were soon referring to Lou’s new nest as “the Garbo apartment.” “He lived for a time near Greta Garbo in an apartment in a high-rise with a doorman,” recalled Bob Jones. “To me it seemed very glamorous—actually it was two rooms. But there was always the drug addict’s lifestyle. There was nothing in the fridge except coffee ice cream. There were records in boxes and things, but that was it.” The apartment fit the Lou Reed mold, furnished with electronic equipment, guitars, stacks of tapes, and a few personal items, such as the plastic plant that he insisted on watering.

“Lou was then wearing the A-head’s uniform,” Jones noted. “When you went out of the apartment, the uniform was quite set—it was a white T-shirt tucked into blue jeans worn with a belt. Boots or shoes, black. A cap of some sort. And very tight, a black leather jacket.

“Lou was getting into gay porn magazines. I remember having the same kind of interest in them as I did in the gory police stuff. It was not erotic to me but I was looking at another world. Because it was forbidden it was interesting—fascinating.”

Lou’s new dog, the Baron, bore a resemblance to Seymour. Lou, admitting that “underneath it all I’m just a sentimentalist,” expressed the same kind of gentle, obsessive feelings toward him. “The Baron is a miniature dachshund with a forceful personality,” noted a friend who visited Reed that January. “He justifies his name by his great ability to corner great chunks of the apartment in which he resides, and subjects all those who enter, including his co-inhabitants, to the random exhibition of his caprices. Mr. Reed, one of his co-inhabitants, is enamored of him. They have an excellent relationship based on Mr. Reed’s acceptance of his menial role in the Baron’s life.”

Reed explained, “I’m here to feed him, walk him, act as chief thrower of chaseable objects and general dog’s body—what an apt description! At first it was difficult, but now that I have learned the wisdom of the Baron’s way, all is well. He’s a total exhibitionist. This morning he displayed a full stem for us, the disgusting little beast.”

When Lou wasn’t in the studio, rehearsing for a tour, or voyaging around the city in search of characters or materials, he spent his time at home, writing songs, playing music, and receiving a stream of visitors ranging from his drug dealers through recording engineers and journalists to guitar players and assorted drug buddies. Ed Lister and Bob Jones would go around to see him and shoot speed. Lou was constantly worried that the police would come to his place looking for Lister—and on one occasion they did, because Lister had left a stolen car in Lou’s parking space.