Chapter Fourteen

The Master of Psychopathic Insolence

1977–78

His credentials are unshakable.

John Rockwell, New York Times, March 13, 1978

“Lou Reed’s angry reaction to his glitter years serves as the perfect dividing point between the early 1970s and the late part of the decade,” Mark Edwards wrote in the London Sunday Times. “Annoyed at the travesty of his original self that he had become, he released Metal Machine Music. It’s an hour of white noise. There is no music on it. Just distortion. Coming out in 1975, it neatly signaled the end of glam as a whole, while the emphasis of the record on nasty, angry, unmusical noise heralded the punk explosion that was to erupt the following year,” Edwards concluded.

1975 was indeed a pivotal year in rock. The glitter scene died. Punk was born. Springsteen arrived. Dylan was reborn. Lou Reed was super-aware of the change. In fact, no single band and no single performer benefited from punk as much as the Velvet Underground and, in particular, Lou Reed.

When punk rock’s New York headquarters, CBGB on the Bowery, opened its doors at the end of 1973, the NY rock scene was mostly populated by touring superstars. The only remnants of the rock underground were the dying New York Dolls and the Berlin-era Lou Reed. Reed’s raw reports from the underbelly of the city were an inspiration that helped open the way for punk rock. Fragments of, among others, the Ramones, Blondie, Television, and Talking Heads began to coalesce as early as 1974. According to M. C. Kostek in the VU Handbook, “Brian Eno’s quip about how not many people bought the Velvet Underground and Nico album but of those who did, everyone went out and formed a band, carried much truth. Many of the most creative people in rock music from the seventies—the Stooges, New York Dolls, Patti Smith, Television, Pere Ubu, Ramones, Richard Hell, Jonathan Richman, Roxy Music, David Bowie, Buzzcocks, Talking Heads, Wire, Cabaret Voltaire, and Eno himself strongly reflect and validate the Velvets’ massive musical influence.”

By the final months of 1975, however, while Lou was recording Coney Island Baby, two powerful streams of rock were surging forward, threatening to leave him in their wake. In the mainstream, Bob Dylan was going through a resurrection, touring with his Rolling Thunder Review and recording his next album, Desire, which would go to No. 1 around the world. David Bowie had, in collaboration with John Lennon, his first No. 1 American single, “Fame.” The new boy, Bruce Springsteen, was simultaneously on the covers of Time and Newsweek. In left field, all the leading punk bands were poised to make the enormous impact they would soon have. Coney Island Baby and Rock and Roll Heart offered little competition to Springsteen’s Born to Run, Patti Smith’s Horses, or the Ramones’ The Ramones. Where was Lou’s place in all of this?

It wasn’t until John Holmstrom’s Punk magazine came along in New York in January 1976, pulling the disparate music of the punk groups together, showcasing them as if they were major stars, that punk could be looked upon as a movement. Holmstrom put Lou on the cover of Punk’s first issue. It was Holmstrom’s view that Reed’s independent spirit, enthusiasm, and dedication to passion made him the ultimate punk rocker. “If you were going to do a rock-and-roll time line, Lou’s there for every decade,” he pointed out. “From doo-wop to garage rock to psychedelic to glitter to disco to punk rock and beyond it later to alternative rock and to sober-rock.” His cover portrait captured Lou’s chemical-insect persona as perfectly as the cover of Coney Island Baby, released the same month, put across his chameleonlike MC role.

Everybody, it suddenly appeared, owed something to Lou Reed. Consequently, in the second half of the seventies when his career could well have taken the nosedive it was in the midst of, Lou was picked and held up by, in particular, Bangs, Meltzer, Holmstrom, Rockwell, Jon Savage, Charles Shaar Murray, Nick Kent, etc.

It was during a visit to CBGB to see the Ramones just before Thanksgiving in November 1975 that Reed had the pivotal encounter that launched him onto the cover of Punk. Only twenty or thirty people were in attendance that night, but the rank, dark little room crackled with the exhilaration of rock in the making.

Sitting at a candlelit table with, of all people, Richard Robinson, Lou was approached by two raw, loony-looking Connecticut teenagers, Holmstrom and the magazine’s resident punk, Legs McNeil, who would shortly become the Johnny Carson and Ed McMahon of the punk scene. “Hey, you!” they accosted him. “You’re going to do an interview with us!” Lou, who was on one of this three-day cruises through the underbelly of the city, watching the parade of geeks and freaks pass before him, fell right into his part, giving one of his best interviews without thinking about it. Lou enjoyed talking to interviewers because they gave him a gloss on what was going on in the rock scene, but later claimed to have no recollection of this particular incident. Holmstrom commented, “He wasn’t getting too many people to talk to him who liked Metal Machine. Danny Fields was there and Legs met Danny, and everybody went nuts because Lou Reed was there that night.” To Legs McNeil, the Ramones’ performance was the most moving thing he had ever seen in his life: “The Ramones came out in these black leather jackets. They looked so stunning. They counted off, then each one started playing a different song. Their self-hatred was just amazing, they were so pissed off.” After taking in the Ramones’ fifteen-minute set, Lou spent the next two hours sparring vigorously with the two punk kids and Punk’s British correspondent Mary Harron.

Lou apparently enjoyed the show.

PUNK: Do you like the Ramones?

LOU REED: Oh, they’re fantastic!

PUNK: Have you seen anyone else that you like?

REED: Television. I like Television. I think Tom Verlaine’s really nice.

PUNK: Do you like Patti Smith?

REED: Oh, yeah, yeah.

PUNK: How about Bruce Springsteen?

REED: Oh, I love him.

PUNK: You do?

REED: He’s one of us.

PUNK: Thank you.

REED: He’s a shit—what are you talking about, what kind of stupid question is that?

PUNK: O.K.

REED: I mean, do I ask you what you like? Why does anyone give a fuck what I like?

PUNK: Well, you’re a rock star!

REED: Oh … I keep forgetting. Why, do you like Springsteen?

PUNK: No, I think he’s a piece of shit.

REED: He’s great at what he does … It’s not to my taste, y’know, he’s from New Jersey … I’m very, y’know, partial to New York groups, y’know … Springsteen’s already finished, isn’t he? I mean, isn’t he a has-been?

PUNK: I feel he’s a has-been.

REED: Isn’t Springsteen already over-the-hill? I mean—isn’t everybody saying that they constructed him because they needed a rock star? … I mean … Already, like, groups are coming out and they’re saying they’re the new Bruce Springsteen, which is really … He was only popular for a week.

Holmstrom couldn’t believe Lou was talking like this on tape. Legs, however, was not so easily won over. During a long discussion of Metal Machine Music and the record business, he started squirming in his seat like an impatient child. “I thought Lou was boring as hell,” he remarked. “I was an eighteen-year-old guy, I didn’t want to talk about art and the record company. I wanted to talk about cheeseburgers, that’s all we had in common. I knew he was like so cool, and I was kind of like, we are not worthy, Lou. But, you knew whatever you did this guy was going to think you were an asshole. He was just too cool.

“Lou has this vibe of not being anyone. The guy just seems completely threatened by everything. But he’s so good, you know, it’s funny, because the punk way to appreciate people is to make fun of them. Like Tish and Snooky used to have a song and it was sung to the tune of ‘Sweet Jane.’ The refrain was ‘Lou Reed’ instead of ‘Sweet Jane.’ ‘Lou Reed’ … then they had all these funny lyrics. So I was paying tribute to him, but I didn’t think Lou appreciated it.”

Halfway through the interview Legs jumped in.

LEGS: Did you ever hear the Dictators’ lyrics—what they said about you?

REED: I hope it’s nothing bad.

PUNK: Yeah—“I think Lou Reed is a creep.”

REED: That’s funny—because when I ran into one of them, he was slobbering all over me saying, “Hey—I hope you don’t mind what we say about you.” And I just pat him on the head—y’know, nice doggie, nice doggie.

Mary Harron, mouth agape, sat through the sparring match with Holmstrom and McNeil. What impressed her most about the hysterically whacked-out interview is the extent to which Lou really looked down on them and how stupid he made them all feel. Out in the street after the interview, she recalled, “John was jumping up and down yelling, ‘We got our cover! We got our cover!’ But Legs flipped out, screaming, ‘Who does fucking Lou Reed think he fucking is?’” Legs felt as if his soul had been taken: “I felt that meeting with Lou, somehow we had been corrupted forever. You felt it in some emotional, stark way. I mean Lou always seemed like he wanted to go darker than sex, murder, mutilation, further. And you always got the feeling that you were definitely an idiot around him. I didn’t want to sit at his feet that night. I didn’t like him. He didn’t seem like a nice guy. I mean, I wouldn’t want to hang out with him.”

Holmstrom, on the other hand, was in a trance, totally persuaded that putting Reed on the cover of their first issue was the most exciting choice possible. “I saw Metal Machine Music as the beginning of the punk-rock movement,” he said. “It was the ultimate punk-rock album. It was the greatest punk statement ever made. It was fuck you to the record company and everyone who bought it. It was, ‘This is what I want to do the way I want to do it.’ How can you get more punk than that? It was more punk than the Sex Pistols, the Ramones, everything that came out afterward. I think he meant it that way, and we treated it that way.”

Punk #1, containing the interview and a glowing review of Metal Machine Music, was published in January 1976, the same month Coney Island Baby came out. It had a terrific impact. Danny Fields praised Holmstrom in the SoHo Weekly News for “inventing a new interview form.” “Instead of a photo, the cover was a wickedly accurate cartoon of Reed as metal man: the feature inside was not typeset but told in fumetti,” wrote the British rock historian Jon Savage. “The surrounding artwork is as important as Reed’s insults: when the interviewers follow Reed down the block, there they are in cartoons. The effect was both immediate and distanced, a formal innovation on a par with Mad magazine or the Ramones’ own manipulations.”

According to John Holmstrom, Lou was impressed. “He said, ‘I barely remember doing the interview and there I am on the cover of this thing.’ He thought it had the whole image thing perfect. I was just knocked out because I was this twenty-year-old kid. And here was this guy who I’d pay seven fifty to see live gushing over my magazine when he hated everything in the world. It just blew me away.” In retrospect, Holmstrom reflected, “Metal Machine Music almost ended his career. He could have become another forgotten Elton John kind of person if we hadn’t put him on the cover. Instead, he became the godfather of punk and it resurrected his career.”

“People who think I got something out of Metal Machine, monetarily or otherwise, should have another think coming,” countered Reed. “All it accomplished was negative. It’ll be that much harder for Coney Island Baby to prove itself. A lot of people got turned off, and I am so happy to lose the people who got turned off. You have no idea. It just clears the air. That’s the end of it. If anybody wanted Coney Island Baby, it was going to be my way.”

Rock-star ranks had swelled by the mid-seventies to such unmanageable proportions that it was hard to know how to distinguish one from another. The cover of Punk picked Lou Reed out of the international swamp and placed him squarely in the vanguard, as a heroic figurehead. The new magazine brought Lou into the forefront of the punk world. Soon Lou was pouring advice into the ears of Tom Verlaine of Television and David Byrne of Talking Heads—mostly about getting a lawyer. But it was Lou’s presence more than anything else that turned everybody on. He went to CBGB in his uniform shades and black leather jacket with Rachel. They sat at a table and listened to the music like everybody else. Lou didn’t grandstand and was obviously enjoying himself. When he saw Patti Smith playing “Real Good Time Together” at CBGB, he was genuinely thrilled, clapping with glee and telling everybody at his table that he had written the song. Johnny Ramone remembered how many of them really began to feel something was happening when Lou started coming to the club.

James Walcott, writing in the Village Voice, had a particularly astute view of Lou’s presence at CBGB:

“Where Lou Reed used to stare death down (particularly in the black-blooded Berlin), he now christens random violence. Small wonder, then, that his conversation ripples with offhand brutality: though he probably couldn’t open a package of Twinkies without his hands trembling, he enjoys babbling threats of violence. One night, when a girl at CBGB clapped loudly (and out of beat) to a Television song, Reed threatened to knock “the cunt’s head off”; she blithely ignored him, and he finally got up and left. No one takes his bluster seriously; I even know women who find his steely bitterness sexy.

“This walking crystallization of cankerous cynicism possesses such legendary anticharisma that there’s something princely about him, something perversely impressive.”

Cale scoffed at the comparisons between the punk bands and the VU: “Everybody’s talking about this band the Velvet Underground influencing this and that. They’re even saying Talking Heads are reminiscent of the Velvet Underground, which has absolutely nothing to do with what we sounded like. And many of these people making these assessments and writing these reviews never saw us live. All they’ve got to go by are live reissues by Lou Reed, that kind of narcissistic nepotism. He just regenerates the same material over and over again, in different form. Lou has his whole life sorted out now. He’s become the Jewish businessman we always knew he was.”

The parallels between Reed’s and Cale’s careers through the seventies reveal just how important image is in rock. As a body of work, John’s solo albums are arguably superior to Lou’s. As Lester Bangs pointed out, “‘Fear’ and ‘Gun’ on John Cale’s Fear are the kind of cuts Lou Reed could be writing now if his imagination had not short-circuited. Unlike much of Reed’s recent work, the music of John Cale is never thin nor euphemized nor needlessly lurid. It is the kind of music that does the Velvet Underground tradition proud, and that’s something to live up to.” Cale’s influence on punk—he produced among other notable works Patti Smith’s first and greatest album, Horses—was arguably stronger than Reed’s. Yet once they went solo, Lou’s image was always stronger than John’s.

But the direct influence of Lou Reed and the Velvet Underground on the punk-rock movement was exemplified by their prominent positions in record charts compiled in fanzines in Britain. Though these charts did not reflect the tastes of mainstream rock-and-roll audiences, they established Reed’s and the Velvet Underground’s popularity with the punk-rock audience. For example, the second issue of Ripped and Torn (January 1977), one of the most widely circulated British punk fanzines, gave “Foggy Notion” by the Velvet Underground the No. 5 position on its singles chart. The same fanzine’s album chart listed six entries (including the No. 1 position) for Lou Reed and/or the Velvet Underground and included every Velvet Underground record.

***

One and a half years later, in the autumn of 1977, Lou prepared to record his godfather-of-punk album. Lou, who in his solo career had made an intense study of recording techniques and become something of an authority on the subject, had discovered a binaural recording process created in Germany by one Manfred Schunke. Schunke used computer-designed models of the average human head. The detail was as precise as possible down to the size, shape, and bone structure of the ear canal. Microphones fit in each ear so theoretically what they recorded would be exactly what a human being sitting in the position the head was placed in would actually hear.

“I had written these songs on the spot in Germany,” Lou said. “I tried to teach them to the band really quick. The audience didn’t understand a word of English—like most of my audience. They’re fucked-up assholes, what difference does it make? Can they count from one to ten?”

Street Hassle was originally recorded at live shows in Munich, Wiesbaden, and Ludwigshafen, Germany. Lou brought the live tapes back to New York for overdubbing and mixing. In what looked like an extremely perverse move, he chose Richard Robinson as his producer. Several of the songs were dated. “Dirt” and “Leave Me Alone” came from the 1975 Coney Island Baby sessions. “Real Good Time Together” hailed from the Velvets’ final years. The title piece, one of the most riveting songs of Lou’s solo career, was written in three parts, “Waltzing Matilda,” “Street Hassle,” and “Slip Away.”

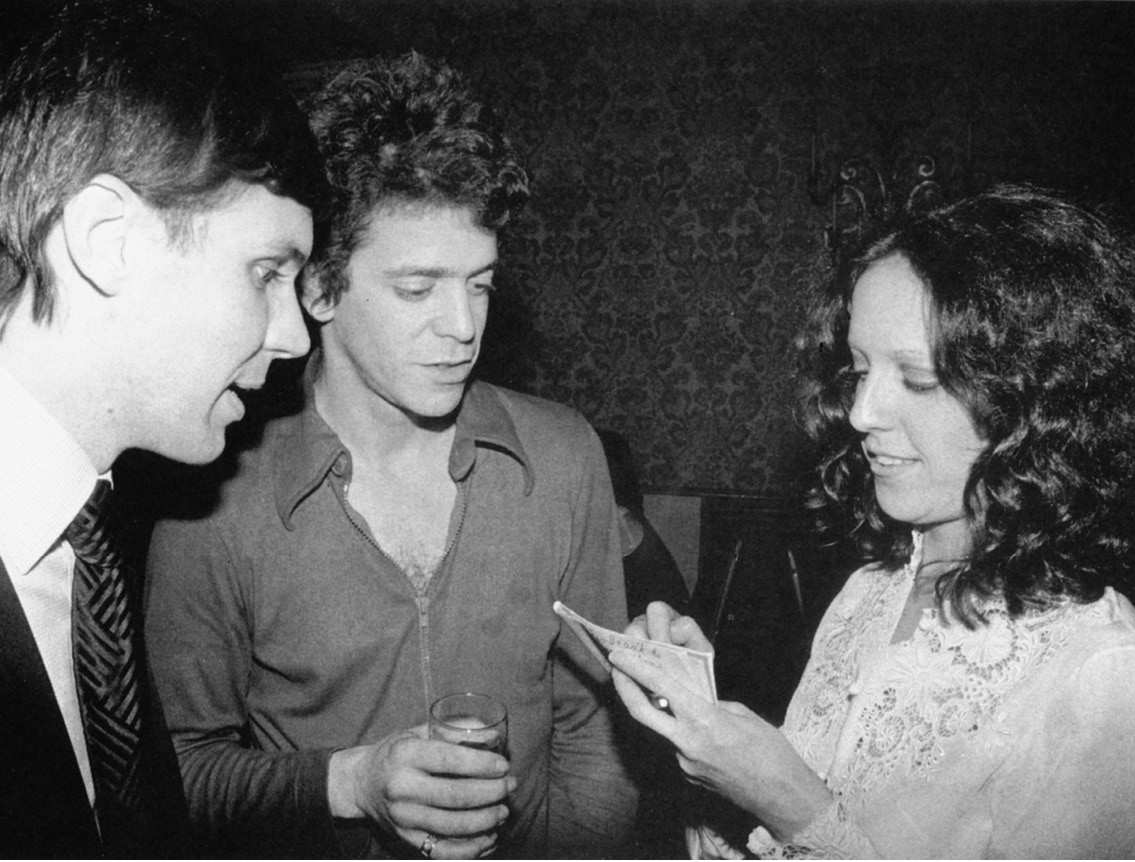

Richard Robinson and Lisa Robinson with Lou Reed, New York, 1976. (Bob Gruen)

Needless to say, all was not copacetic in the studio. Lou’s father–son relationship with Clive Davis would come to a head during the Street Hassle sessions.

After hearing an early version of the last section of “Street Hassle,” Davis suggested Reed make the two-minute track longer. Although Lou accepted Clive’s advice (“I wrote the lyrics for ‘Street Hassle’ out from beginning to end in about as long as it took to physically write it on paper”), he later complained of “being betrayed by all the evil people around me! The original producer [Richard Robinson] had walked out, I’d had to change studios because we had a fight there—and then Clive Davis came in and told me I should make a new record and throw this one away. But the record came out, and I wasn’t crazy. They were just stupid. The head of Arista was stupid.”

Making albums allowed Lou to be the Sylvester Stallone of rock, both directing and starring in the works. “Some people make movies of people who interest them,” Reed was quoted in an Arista press release. “Andy Warhol has been doing it for years … Actually, I do it with my songs.”

Displaying what he had learned from Warhol, Raymond Chandler, and Delmore Schwartz, Lou wrote a vivid story with short, neo-Céline-like sentences. The song, which ends the cycle about Rachel that began with “Coney Island Baby,” laments the end of their relationship. As Bob Jones, who was also at the end of his relationship with Lou, said, “At a certain point the only way to be around Lou was to be secondary to Lou, and you either had to become an acolyte—which was a role that I don’t think Lou would allow one to continue—or say good-bye. It would very much be part of the attitude of the time that one would say good-bye in a cynical way and be tough and rough about it.”

One of the many nuggets in “Street Hassle” came from the unexpected contribution of Bruce Springsteen, who sang a few intense lines in the center of the piece. “He was in the studio below, and for that little passage I’d written I thought he’d be just perfect, because I tend to screw those things up,” Reed recounted. “Like ‘I Found a Reason,’ it is my best recitation, but I just couldn’t resist that ‘Walking hand in hand with myself’ part. I’m too much of a smart-ass. But I knew Bruce would do it seriously, because he really is of the street. Springsteen is all right, he gets my seal of approval. I think he’s groovy.”

The most striking thing about Lou’s relationship with Rachel was how long it lasted, particularly considering that they spent virtually all of their time together. Unlike his relationships with previous girlfriends and his wife, Lou did not immediately try to push Rachel to an edge. Whether this was because he knew how much he needed her or because Rachel’s personality was able to absorb Lou’s blows without flinching, there’s no question that from late 1974 through 1977, Rachel was a mainstay of Reed’s life. And her personality permeates the albums from Coney Island Baby, a paean to Rachel that put Lou squarely on the map as the poet laureate of the gay world in New York in the seventies, to Street Hassle, which documents the sad conclusion to their affair.

The breakdown started somewhere in 1977. A friend visited Lou one afternoon that spring to find him alone and brooding over Rachel’s disappearance. Speaking in the tone of a bereaved lover out of a broken-hearts novel, Lou was in despair and blaming himself for the break, crying plaintively that he would do anything to get her back. He was about to go on tour and remarked wistfully that they could have had such a ball together, but now everything was in doubt.

Two days later Lou got a phone call instructing him to go to a downtown bar where a surprise awaited him. Hastening to the specified location, Lou walked in to find Rachel sitting at the bar with open arms and a sweet smile. In such moments, Lou was the most romantic of men. He swept her off her feet again and they did have a ball on the subsequent tour. But in such intense relationships, once a crack like that appears, there is little chance of real recovery.

Although he clearly regretted it, by early 1978 Lou and Rachel were having a trial separation. Again, quite uncharacteristically, when Lou did break up with Rachel, rather than closing her out of his life with a slammed door, Reed admitted that he still had strong feelings about her and missed her. Ultimately, the relationship probably suffered more than anything else from writer’s syndrome. When a writer makes use of his mate for his material, he risks losing the indefinable essence of their connection. Rachel should be remembered in the saga of Lou Reed as the muse who helped give birth to his finest work of the mid-seventies.

***

The first half of the seventies had been a prolific time for Lou Reed. He produced six studio albums and completed a book of poems, All the Pretty People. “They have a certain progression,” Lou explained. “From the start they got rougher and harder and tougher until it’s just out and out vicious, doesn’t rhyme, and has no punctuation, it’s just vicious and vulgar.” Largely through the auspices of Gerard Malanga, who remained Reed’s astute connection to the poetry world despite Lou’s rejection of his friendship and criticism of him in print for getting the poems published, several poems were published in literary magazines, ranging from the prestigious Paris Review through Unmuzzled Ox to underground publications like the Coldspring Journal. In late 1977, shortly after he finished work on Street Hassle, Lou won a prize for “The Slide” published in the Coldspring Journal, as one of the year’s five best new poets from the American Literary Council of Little Magazines. He attended the ceremony at the Gotham Book Mart in New York and was given the award by Senator Eugene McCarthy. Lou wondered if McCarthy read his poems about S&M, noting, “He was taller than he seemed on TV.”

Street Hassle was released in February 1978 at the commercial height of the new wave and marketed as a grand statement from the man who invented punk. It received more press than anything Reed had done before, garnering reviews from Time to Punk. It took him to the pinnacle of his career as reviewers around the world praised it to the skies. “I’m right in step with the market,” he said in Creem the week the album came out. “The album is enormously commercial.”

An article in the NME in 1993 looked back at this period:

“Signs of his rejuvenation were most vividly apparent on his 1978 tour de force Street Hassle, an uncompromising howl of self-lacerating disgust and poisonous venom that against all odds turned out to be one of the major albums of the late seventies. The title track ranks with anything on the more celebrated New York, Songs for Drella, or Magic and Loss. In its final heartbreaking conclusion, Lou sounds exposed and vulnerable and hurt beyond words. “Street Hassle” takes you to the edge and leaves you there—darkness below, no lights in heaven above.”

“I keep hedging my bet, instead of saying that’s really me, but that is me, as much as you can get on record,” Reed elucidated. “I use my moods. I get into one of these dark, melancholy things and I just milk it for everything I can. I know I’ll be out of it soon and I won’t be looking at things the same way. For every dark mood, I also have a euphoric opposite.”

Lou did a series of interviews, including an outstanding one with Allan Jones for a British magazine, Melody Maker, in which he put himself in perspective:

“The Velvet Underground were banned from the radio. I’m still being banned. And for exactly the same reasons. Maybe they don’t like Jewish faggots … No. It’s what they think I stand for they don’t like. They don’t want their kid sitting around masturbating to some rock-and-roll record—probably one of mine. They don’t want their kid ever to know he can snort coke or get a blow job at school or fuck his sister up the ass. They never have. But how seriously can you take it? So they won’t play me on the radio. What’s the radio? Who’s the radio run by? Who’s it played for? With or without the radio I’m still dangerous to parents.”

When another interviewer, the kid who had arranged Reed’s first solo gig in the U.S. in 1972, Billy Altman, noted, “One thing that disturbs people about your music is its lack of what might be called a moral stance,” Lou shrugged in disdain, saying, “They’re not heterosexual concerns running through that song. I don’t make a deal of it, but when I mention a pronoun, its gender is all-important. It’s just that my gay people don’t lisp. They’re not any more affected than the straight world. They just are.”

“Street Hassle is the best album I’ve done,” he told another journalist. “Coney Island Baby was a good one, but I was under siege. Berlin was Berlin, Rock and Roll Heart is good compared to the rest of the shit that’s going around. As opposed to Street Hassle, they’re all babies. If you wanna make adult rock records, you gotta take care of all the people along the way. And it’s not child’s play. You’re talking about managers, accountants, you’re talking about the lowest level of human beings. Street Hassle is me on the line. And I’m talking to them one to one.”

In the second half of March 1978, Reed played a five-night residency at the Bottom Line in New York with his favorite mid-seventies combo, the Everyman Band. Susan Shapiro described the shows in the Village Voice:

“Onstage he’s puckish, like Chaplin, like the cover of Coney Island Baby, a live highlight. He moves like a go-go gymnast, awkwardly, authentically, uncorrupted by vanity. He’s singing ‘I Wanna Be Black,’ but it’s playful, a lie to tell the truth. ‘Satellite of Love’ and ‘Lisa Says’ top one another. The force is with him and he’s maybe taking ‘yes’ for an answer. Wallace Stevens has nailed him, ‘under every “no” lay a passion for “yes” that had never been broken.’ Then he’s given them the whammy, ‘Dirt.’”

“People are always looking for a voice that works,” noted Henry Edwards. “It took him years to find a strong performing voice. It was in him and he didn’t let it out. Because he was so busy playing the faux junkie. I was amazed when I went to the Bottom Line in 1978 and he really was a rock-and-roller.”

Andy Warhol wrote in his diary: “Lou was late coming out, but then he did and I was proud of him. For once, finally, he’s himself, he’s not copying anybody. Finally he’s got his own style. Now everything he does works. It took years and Lou just kept on working. He’s very good now, he’s changed a lot.”

“Andy always understood where I’m coming from,” Reed responded. “He also said to me that work is the most important thing in a man’s life and I believe him. My work is my yoga. It empties me out. Years ago he said I was to be to music what he was to visual arts. The man’s amazing. You can’t define it, but it’s happening just the way he said it would.” The shows were recorded for a live album to be called Take No Prisoners. Reed noted, “We called it Take No Prisoners because we were doing a quite phenomenal booking in a tiny hotel in Quebec, where they’d normally have a little dance band. I dunno what we were doing there, but … All of a sudden this drunk guy sitting alone at the front shouts, “Lou, take no prisoners, Lou!” and then he took his head and smashed it as hard as he could to the drumbeat. We saw him doing it and we were taking bets that that man would never move again. But he got up and bam bam on the table! And that was only halfway through. What was gonna be the encore? He might cut his arm off!”

The fastest mouth in rock and roll combined his Method-acting, stream-of-consciousness spontaneity, and Lenny Bruce-style wit to make a record unlike any other. The songs became background to the monologues—slapping down members of the audience, reeling off a succession of slick one-liners, throwing darts at Patti Smith or Andy Warhol, playing out every lyric for its full sexual innuendo.

As Reed recalled, “It is a comedy album. Lou Reed talks and talks and talks. Lou Reed, songwriter, is dried-up—ran out of inspiration … Would you buy a used guitar from Peter Frampton?” Reed saved his most acidic bile for rock critics—notably John Rockwell of the New York Times and Robert Christgau of the Village Voice. “Who needs them to tell you what to think?” he railed before lecturing his audience.

Lou’s outbursts on Take No Prisoners reveal a Lou Reed who is autonomous because he can talk back to himself. “What are you complaining about, asshole?” he asks himself, answering, “I just play the guitar.” Later he quips, apropos of a literary reference, “for those who still read,” then turns on himself, snapping, “What a snotty remark.”

Despite the hatchet for a tongue with which he chopped Christgau and his ilk, Lou in fact continued to relate to journalists around the world as if they were his best—no, his only—friends. Bert van der Kamp recalled, “In 1978, at the end of the interview, he said to me, ‘It’s always nice to talk to you, you’re such a good friend.’ And I said to him, ‘Why did you act like you didn’t know me?’ and he said, ‘Well, I wanted to be sure it was you.’”

Lou kept in touch with Punk’s John Holmstrom, but Reed was a tough man to have as a fan. “I would run into him occasionally, but he was very down on the magazine after we did him,” John recalled. “He’d say, ‘Oh, you blew it, it’s not as good as it used to be.’ And he was right. He was always drifting away from us, then drifting towards us.”

When Punk held its award ceremonies in October 1978, Reed was nominated for the Punk Rock Hall of Fame Award. Lou accepted the invitation to attend the ceremonies. As John recalled the night:

“We thought we were going out of business and we wanted to have a party and go out in style. A day or two before our party, Nancy Spungen was found dead. So New York went nuts. It was a crazy time and all the insanity focused on our event, because we were the punk event happening at the moment. TV crews came down and wanted to interview all the punk-rock stars about Sid and Nancy, and nobody wanted anything to do with this because people were shocked and horrified by what had happened.

“The media were always more interested in promoting those aspects of punk. They could have said, for example, that Lou was a great artist who expressed himself differently. But they had to focus on the ridiculous, shaving Iron Crosses in the side of his head. Which to us was not the point. Punk to us was more the attitude: you do what you want artistically and any other way, lifestyle-related, and screw you. Not that you have a tawdry or decadent lifestyle and get nasty about it. It was more like the ultimate individual against perversion.”

What had been intended as a humorous ceremony deteriorated into a horror show owing to the hysterical intervention of the local press. The audience started breaking the furniture and throwing it at the stage and booing.

Legs McNeil remembered “Lou laughing a lot. We gave him an award. I don’t know what for. I’m sure it was really amateurish and stupid. It was the Punk Awards!” But Holmstrom saw a different reaction: “Lou accepted the Hall of Fame award. But he wouldn’t come up onstage, he just took it and walked out. We had a big falling out over the awards ceremony. It was a disaster, it was horrible. Before the thing he had said, ‘If you embarrass me, I’ll never speak to you again.’ And he was embarrassed. That was the last time he ever talked to me.”