Mr. Ben woke them early the next morning, as they had asked him to do, and they emerged reluctantly from sleep. It was dim in the room, and the world outside seemed gray and one-dimensional, still shadowed by night. “It looks like rain,” he said. “You better go do your fishing and then come back for breakfast. Maybe you’d better start home right after that. If that road gets much rain you’ll be in trouble.”

“Yes, sir.”

They got up and dressed silently in the living room, collected their gear, and went down to the wharf. The first streaks of color were coming into the sky, dyeing the overcast; they both felt half-awake and a little remote from the world, as though they were still dreaming. Although it had got a little warmer during the night, thin wisps of mist came off the water and thickened and trailed languidly over the Pond, giving their surroundings an unsubstantial and faintly eerie air. Neither of them spoke. Bud took the paddle and got into the stern of the boat.

“You fish,” Joey said.

Bud shook his head.

“You venched on him.”

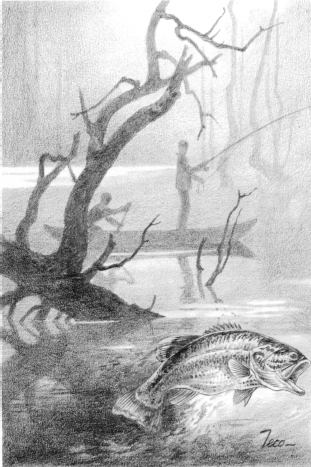

Bud shook his head again, and Joey climbed into the bow, picked up his rod, put the spotted wiggler on his line, and sat down. The seat was wet from the night’s dew and soon soaked through his trousers. They shoved off and slid silently through the trailing mist; presently the clump of cypresses materialized fragmentarily through it, Bud stopped paddling, and Joey cast. The excitement that he should have felt wasn’t in him, and he wasn’t surprised when the big bass didn’t appear. He cast mechanically several more times and laid the rod down on the bottom of the bateau. The whole thing had been an anticlimax, without savor, and he wished that he hadn’t come out. “Let’s go back,” he said.

“Okay,” Bud said, and paddled back to the wharf.

They caught the fish in the live box, strung them on a small tree branch, and took them up to the house, wrapped them in newspaper, and put them into the Model T. They cooked breakfast, ate it, and packed up. They said so little to one another that Mr. Ben looked at them searchingly several times but didn’t say anything. They had lost touch, Joey because of his scheming about the frog and Bud because he felt that something was wrong between them and couldn’t define it, and he wasn’t going to ask. They finished their packing, stowed their gear into the Model T, and shook hands with Mr. Ben.

“Maybe you’ll see the alligators next time,” he said, grinning at them. “What will I tell Charley when he comes over for breakfast?”

“Tell him I’ll … we’ll bring some dog food next time,” Joey said. “We sure thank you, Mr. Ben.”

“Yes, sir,” Bud said. “Thank you very much.”

Mr. Ben stood on the porch watching as Bud cranked the Model T, and waved as they turned the corner of the house and went out the lane. At the gate they saw Charley trotting down the road; he stopped when he saw the car, watched it come through the gate, and turned home.

* * *

They stopped at Pitmire’s store and left a fish, and after a muddy but uneventful trip got to Richmond. It began to rain as they reached the city limits, so they decided to leave their gear in the Model T until after it had stopped. Joey dropped Bud at his house, which was close to Joey’s; their parting was a quiet one.

“Thank you, Joey.”

“Okay. I’ll see you.”

“I’ll see you.”

Joey drove around the block to the alley, put the Model T in the garage, picked up the fish and walked through the long backyard to the kitchen door. The maid, Mary, a small, skinny Negress whose age no one had ever been able to guess, let him in.

“Hi, Mr. Joey. Your maw’s been worryin’ you get stuck in them roads and fall in the lake and get lost in the woods. You do any of ’em?”

“Not any,” Joey said, and put his package on the table.

“What’s that? You got fish in there? You gon’ mess up my kitchen with fish?”

“I have to clean them. One’s for Bud.”

“You ain’t goin’ do any such thing. Lawd, Lawd. Fish scales an’ fish guts … No, suh. Anybody cleans ’em I cleans ’em. You go on, now. Your ma be home presently.”

She shooed him out of the kitchen. He went into the dining room, with its big, glass-domed, fringed lamp hanging over the center of the golden oak dining table, pausing to throw the wall switch rapidly six times to see the opalescent colors of the glass. Mary stuck her head in the door.

“You quit that, you hear? You had any lunch? You better take a bath. I bet you ain’t washed your face since you been gone. You take a bath, and I fix you some lunch.”

“Okay,” he said, and went through the living room and up the stairs, into his father’s “study” at the rear of the house. It was a disorderly room crowded with overstuffed chairs, a big leather-covered couch, bookcases, a flat-topped desk, and a gun cabinet; the closet was full of outdoor clothes and fishing tackle and the desk and bookcases were piled with sporting magazines and catalogues. Joey’s father was in the insurance business, but his heart belonged to the quail, the ducks of lower Chesapeake Bay, and all fish that showed spirit. Joey rooted about until he found the Sears, Roebuck catalogue, opened it to the page showing the Kalamazoo frog, and placed it in the middle of the desk. Then he went to his own room and changed his clothes; he wet his hair, washed his face and hands with a minimum of water in the bathroom, and went downstairs again. The fish had disappeared and his lunch was ready; he sat down at the kitchen table and ate it.

He was just finishing it when his mother came in. She was a pretty woman, tall and fair; there was an air of quiet good humor about her, and she smelled good when she kissed him. She had been downtown, and had on a big flowered hat and the suit that Joey liked; her umbrella was wet. “I didn’t expect to see you so early, honey,” she said. “Are you all right?”

“Yes’m. Mr. Ben thought we’d better come back before it rained too much on the road.”

She put her umbrella in the sink. “I’m glad he thought of it. Were you polite to him?”

“Yes’m.”

“I hope you got enough to eat.”

“Yes’m.”

She glanced at Mary and shook her head with humorous resignation; she had long since given up any hope of getting more than a very bare report of his activities from him.

“I tole him to take a bath,” Mary said. “He comes in smellin’ like coal oil and smoke an’ I don’t know what, but he jus’ wet his hair an’ thought he fooled me.” She snorted.

“I don’t need a bath,” Joey said. “How could I get dirty down there, for gosh sake? We didn’t even have to wash the dishes. Mr. Ben washed them, because he had dirt in his hands and the dishwater takes it out.”

Mary cackled. “Miz Moncrief, you hear that? He been washin’ in dishwater when he wash at all. Ain’t no dishwater get very dirty from him, I reckon.”

“Take a bath, Joey.”

Joey saw that the battle was lost. “Heck,” he said and went upstairs again. He undressed, ran the tub full of water, and stretched out in it. Presently, lying quietly in the warm water, he fell into a semi-somnolent state and lived over again the excitement of the squirrel hunt and the first attacks on the bass, and moved on. In the reverie that engaged him there was nothing unpleasant like his falling-out with Bud; Bud was forgotten, and didn’t even appear. As his reverie progressed only he and the splendid things he was going to do in the future were in it; for now that he had been to the Pond without grownups and got an intimation of what it could hold for him, his reaction to the world about him was changing, or had already changed.

He fell asleep in the warm water after a while, and only waked up when his father came into the bathroom and gently shook his shoulder.

“Wake up, boy,” his father said. “You’ll drown in all that water if you’re not careful.”

“Hi, Dad. Dad, can I have a Kalamazoo frog?”

His father, tall, lean, dark-haired, and ruddy, looked at him in puzzlement. “A what frog?”

“Kalamazoo, Dad. It only costs sixty-eight cents. It kicks when you pull it.” His father still looked puzzled. Joey stood up in the tub, reached for a towel, and began to dry himself. “Wait a minute,” he said. “I’ll show you.” He finished drying himself, ran naked into the study, and came back with the catalogue. “Here,” he said. “This is it.”

His father looked at the frog, and read about it. “I couldn’t figure out what you were talking about,” he said. “Do you think it’s any good?”

“Yes, sir. Could you get it tomorrow?” He began to put on his underwear.

“Get some clean underwear.”

“Yes, sir.” He ran into his bedroom, grabbed a clean union suit from a bureau drawer, put it on, and came back to the bathroom again. His father wasn’t there, so he went into the study and found him sitting at the desk. “I can have it. Can’t I? Please, Dad?”

“What’s all the rush, Joey?”

Joey squirmed. “It’s a sort of a secret,” he said. “I want to go down again soon, and I have to have it. And a hunting license. We didn’t have hunting licenses.”

“Did you hunt?”

“Yes, sir. Mr. Pitmire said it would be all right. Mr. Ben borrowed White’s squirrel dog, and we hunted with him.”

His father regarded him for a long moment, recalling his own youth, and his estimation of the whole situation came close to the truth; he suspected a very large fish in the background, and thought he knew what was going to happen about catching it sooner or later. He didn’t want to inquire too closely, for he knew that Joey would have to work things out for himself. He remembered the secrecies, the aspirations, the fumblings, and the discoveries of his own boyhood; he wished that he could talk to Joey about these things and help him, but he knew that he could not. “All right,” he said finally. “I’ll get you the frog. It might take a few days, but you won’t be going down for another two weeks, until Thanksgiving vacation.”

“Yes, sir,” Joey said, immensely relieved. “Can I stay longer this time?”

“If you want. Did you get any squirrels or any fish?”

“Yes, sir. We got four squirrels, but the dog ate them. They don’t feed him, Mr. Ben said, so we’ll feed him next time and put the squirrels where he can’t get them. We got some fish, too. Mr. Ben’s nice, Dad.”

“Mr. Ben’s all right. You mind what he tells you.”

“Yes, sir.”

Joe Moncrief stood up, and laid his hand on Joey’s shoulder. He was a little envious of the boy, just starting out. “If you need anything else before you go, you tell me. You’d better get ready for dinner now.”

“Yes, sir. Thank you, Dad.”

“You’re welcome, friend. Maybe I can get down for a day or two while you’re there.”

“It would be fun if you could,” Joey said, and went off to his room to dress.

The time crawled by, and Joey thought it would never pass. He rode his bicycle to school, played sandlot football in the afternoons, and did a modicum of studying in the evenings; he was often dreamy and absent-minded in class. His father brought home the license and a new belt knife, and, after a few days’ delay, the frog. It was a wonderful thing, made of rubber and realistically spotted; he kept it on his bureau and tried to make it work in the bathtub. The bathtub was too short, but he got an idea of how he would have to manage it; after he got the frog the time went by at an even more reluctant pace.

He saw Bud every day; their relationship was friendly but lacked the warmth and interest in each other’s doings that it had formerly had. Although Bud mentioned the Pond several times, Joey didn’t encourage talk about it; he had decided that he wouldn’t ask Bud to go with him at Thanksgiving, and didn’t mention that he was going himself. They weren’t in each other’s houses all the time, as they had been formerly, and Joey’s mother asked him about it.

“Have you and Bud quarreled, Joey?”

“No, ma’am.”

“He’s not here any more.”

“He’s sort of busy, I reckon.”

“His mother asked me what had happened to you.”

“I’ve been sort of busy too, with my frog and everything.”

“Joey, are you sure …?”

“Yes, ma’am, I’m sure.”

“Well, that’s good. I’d better talk to his mother about your Thanksgiving trip.”

There was a silence, and Joey’s toe dug into the Brussels carpet. “Mom,” he said finally.

“Yes, Joey?”

“Mom, he …” He paused; he had almost said that it was Bud who didn’t want to go, but at the last minute decided to tell the truth. “Mom, I don’t want him to go.”

“Oh, Joey. I thought there was something. What is it, Joey? Tell me.”

“It isn’t anything,” Joey said. He didn’t want to tell her that Bud had no desire to shoot squirrels, and about the frog. It was a private thing, one of the privacies that grownups were always prying into for no reason that he could see. “Mom, it isn’t anything. It isn’t.”

“You’re sure you haven’t quarreled?”

“No, ma’am. We’re playing football together this afternoon.”

She looked at him for a moment, with love and a little melancholy, acknowledging that this mysterious masculine performance showed all too clearly how he was growing up, growing away from her. “All right,” she said. “But we’ll have to ask your father. He may not want you to go alone.”

“Okay,” Joey said, puzzled in his turn as to why it had all become so complicated. “Can I go play football now?”

“Yes,” she said. “Kiss me.”

He kissed her quickly and a little sheepishly, and went out.

He wanted to be home when his father got there, but a quarter of a mile from the lot where they played football he had a puncture in his front tire and had to walk his bicycle the rest of the way. Further tribulations caught up with him two blocks from home, in the shape of a boy named Jerry MacDonald, who was in charge of the Christmas bonfire. Practically every Richmond family kept their trash for weekly collection in wooden barrels at their back gates; and every group of neighborhood boys—“gangs” as they called themselves—stole these barrels for a month before Christmas, hoarded them somewhere, and burned them on their favorite corner for three or four days during the holidays. These fires were kept burning day and night by details who were appointed far ahead of time; parental permission for the details was obtained early; it was the most important event of the year. A gang was respected for the splendor of its fire, and the gang members sat about on boxes, set off firecrackers, and discussed matters of interest while their parents visited one another and drank eggnog and ate fruit cake. These were ancient customs, the origins of which were lost in the mists of the past.

Jerry hailed Joey from his front porch, and came down to the street. “I just finished making my list up,” he said. “You reckon you could be at the fire the night after Christmas? Early in the morning, I mean.”

“I reckon so,” Joey said. “How early?”

“From four to eight, maybe?”

“Why do I have to get up that early, for gosh sake? I’d rather be there from seven to ten.”

“You were there from seven to ten last year,” Jerry said. “You had it easy.”

“You had it easy yourself. You were there in the daytime. I bet you’re going to be there in the daytime this year, too.”

“All right, I am, but I have all the work to make up the list, don’t I?”

“I don’t think it’s fair,” Joey said, passionately, and saw his father’s car stop before the house. “I got to go.”

“You can’t go until you tell me about the fire.”

“Gosh hang it, I don’t want to get up at four o’clock in the morning.”

“The only other thing I’ve got is two turns on the last day.”

“I’ll take—” Joey began, and caught himself. He might want to go to the Pond then, he thought. It was three days after Christmas, and they might let him go by that time.

“I can’t be there then. I might go away.” He began to move his feet restlessly. “I got to go, I tell you.”

“You’ve got to take the first one, then,” Jerry said, and grinned like a possum at him.

“Okay! Okay!” Joey shouted and trotted off, pushing his bicycle, scowling, and grumbling to himself over the heaviness of his social obligations. He was still grumbling when he reached home, and then forgot the encounter in the uneasiness he felt over his coming interview with his father. He took his bicycle through the passageway beside the house and left it in the backyard and looked down at himself. His knickerbockers were dusty, his hands were grimy, and one of his long black stockings was torn, so he went in through the kitchen, up the back stairs, and changed his clothes before he went to find his father in the study. Joe Moncrief was looking through a gun catalogue and glanced up as Joey stopped in the doorway.

“Hi, Dad. Dad?”

“Hi, Joey. Come on in.”

Joey went in and stood in the middle of the floor. “Dad, did Mom tell you … I mean, I reckon you talked with her.”

“You mean about Bud?”

“Yes, sir,” Joey said in apprehension.

“What’s it all about?”

“I wanted to go by myself.”

“Why?”

His father’s eye was on him, and he knew that he would have to come up with a reason this time; he squirmed. “He just doesn’t want to shoot squirrels,” he blurted out. “He just wants to fish all the time.”

“And there’s only one Kalamazoo frog?” Joe Moncrief asked. His original estimate of the situation was working out as he had suspected it would.

Joey didn’t say a word; he looked at the floor.

“Well,” his father said, after a bad moment, “I think it’s all right. I don’t want you driving alone, though. I’ll write Ed Pitmire and have him meet you and take you over.”

Joey breathed again; a great smile appeared on his face. “Thanks, Dad,” he said. “Dad? He’ll just be for you and me, huh? I mean, if I don’t … I mean …”

Joe Moncrief smiled at him. “Sure,” he said. “Don’t rush it now. Big fish are smart. Take your time.”