Ed Pitmire’s driving technique was simple; he pulled the throttle lever all the way down when he started to go somewhere and never touched it again until he arrived. The engine roared, knocked, and rattled, the mud flew and the car swayed, bucked, and did its best to hurl its passengers over the semi-opaque windshield or over the side. Joey hung on to anything he could reach and enjoyed himself. Pitmire presided over the uproar with an Olympian calm, with most of his attention on the woods; once he stopped, reached down for the shotgun beside him, blasted away at a squirrel, jumped out and retrieved it, threw it in the back of the Model T, and drove on. Occasionally he would shout something unintelligible and Joey would shout back affirmatively.

They tore across the spillway, roared up the hill, turned in the gate, and stopped behind the house. Pitmire killed the engine; the silence was like the silence on the first day of creation, profound and almost unbelievable. Joey looked around, delighted to be back. Mr. Ben came out of the house, and as he walked toward the car Joey reached into the back and came up with the package his mother had given him.

“Hi, Mr. Ben,” he said, handing him the package. “My mother sent you this.”

Mr. Ben grinned and opened the package; a dark blue sweater, heavy and warm, was in it. “Why, thank you, Joey,” he said, pleased. “It’s real nice to be remembered. I’ll write your mother a letter. Come in awhile, Ed. I’ve got something that will pass for coffee.”

“I’ve got to get back,” Pitmire said. “Some people are doin’ their shoppin’ today and Liza don’t feel so good. I’ll help you unload.” He got out of the car and hoisted a big can out of the back. “I didn’t know you’d gone in the dog business.”

“Dog business?”

“Got twenty-five pounds of Spratt’s dog biscuits in here. Mr. Moncrief had me get it.”

“Oh,” Mr. Ben said, and grinned again. “Joey and I went into partnership awhile back. Just put it on the porch.” The three of them unloaded the car, piling a small mountain of food and gear on the porch, and Pitmire waved at them and left, almost taking the corner of the house with him. As they listened to his headlong progress down the hill Mr. Ben shook his head. “He’s wasted around here,” he said. “The Roman chariot races could have charged extra to see him.”

“Yes, sir,” Joey said. “It was a pretty wild ride, but we got here. I reckon I better put the things away.” He began to carry the things in and stow them. When he unpacked the frog, he took it into the living room and showed it to Mr. Ben.

“It just might work,” Mr. Ben said, examining it. “Nobody’s thrown anything like it at that fish before, that I know of. You wait until almost sundown, and then try it.” He handed it back. “You’ve a visitor outside.”

Joey went to the porch window; Charley was sitting near the bottom of the steps, looking at the kitchen door. “Great day!” Joey said, vastly pleased. “He knows I’m here.” He went out, and when he got to the bottom of the steps extended his hand. “Come here, Charley. Come see me, boy.”

The dog cocked his head; his tail stirred a little, but he remained where he was. Joey’s disappointment showed in his face; he stood there for a moment and then recalled the dog biscuits. The can was still on the porch and he went back and got two square, thick biscuits out of it; returning to the foot of the steps he held one of them out and spoke to the dog again. Charley licked his chops hungrily but didn’t move; only his eyes showed how much he wanted the biscuit. Joey was puzzled; he had never seen a hungry dog act in such a fashion, and didn’t know what to do next.

“Put it on the ground,” Mr. Ben said from the porch. “Nobody ever handed him anything before. If they did, likely it was to get him close enough to kick.”

Joey dropped the two biscuits on the ground and joined Mr. Ben on the porch. As soon as he was there Charley got up and came over to the biscuits, bolted them, and sat down again.

“Take him one, now,” Mr. Ben said, “but don’t try to get too close to him.”

Joey did as advised. Charley watched him approach, and half stood up to move away. Joey squatted down and extended his arm full length. The dog looked at him for a moment, ready to jump aside, and then stretched his head forward and took the biscuit daintily in his teeth; then he moved off a little and ate it.

Joey returned to the porch; he was disturbed by what he had seen. “Mr. Ben,” he said, “how could they treat him so mean that he acts like that? They’re cruel to him.”

“They’re not really cruel,” Mr. Ben said. “Or they don’t mean to be. It’s just the way they are with animals; lots of country people are like that. An animal to them is sort of like a machine or a plow or a shovel. If it does something they don’t think it should they bat it one. Besides that, Sam White’s got such a nasty temper sometimes he’s rougher than most. He’s got a mule over there he’s pounded so much it’ll turn around and kill him one of these days. Don’t you ever get near it.”

“No, sir.”

“You remember that. That mule’s smart. He stores up all the whacks he’s had, and he waits for one real good chance to get even. He knows he’s not going to get more than one. He hates the whole human race. You stay away from him.”

“Yes, sir, I will. Charley did take the biscuit from me, though. Maybe he’s beginning to know I like him.”

“You take it slow and easy with him. He’ll come to you presently.”

“Yes, sir. I reckon I’ll go squirrel hunting now.” He went into the house, put his gun together, and changed into his hunting clothes. The bedroom, bare but clean, was chilly; it would get colder all winter, and Joey wondered fleetingly whether he would be comfortable in the bed without Bud to help him warm it up. Now that Bud wasn’t there he missed him, but he didn’t dwell on this or even acknowledge it. His mind was too full of anticipation, of killing squirrels and being there and free to do as he wished. He went outside and whistled to Charley and started off for the woods.

The dog came after him as before, and moved out ahead of him when he came to the trees. He knew what he was about now; it wasn’t like the first time, when neither he nor Bud knew what they were supposed to do. When he paused to listen for Charley’s voice, the woods around him, so silent and still, suddenly seemed to be full of a brooding mystery; a feeling came over him that the woods withheld from him, just beyond the compass of his eyes and ears, a secret that he couldn’t penetrate. It was like standing before a closed door and not knowing how to open it. This was a feeling that he was going to have again and again when he was alone: a waiting and a reaching-out to know and be merged with the mystery, an exaltation and a yearning. Many woodsmen have had it and are only completely happy when they are lost from the outside world and on the edge of it. It drove the mountain men of the early American West into the silence and loneliness of the Rockies and still sends its acolytes far into wild places where they can be alone.

When the dog began to bay in the distance Joey, who had been standing in a trancelike immobility, shook his head and stood for a moment collecting himself. He was a little shaken by his first exposure to an experience as mystical and moving as the experience of religion, or the more universal but equally mysterious one of falling in love with one woman. To put it simply, he had fallen in love with the woods; like every lover, he would make many fumbling mistakes before he understood his love.

He found Charley at the base of a very tall cypress near the water. The squirrel was curled around the tip of the trunk, and seemed halfway to Heaven. In Joey’s mind it was already in his game pocket; he raised his gun and shot, but the squirrel didn’t move. It was so high and its hide was so tough that the shot didn’t penetrate it.

Joey had a rather hazy notion of the range of his gun, and he couldn’t believe his eyes. He shot again. The squirrel was stung and stirred a little, but stayed where it was. Joey fired at it twice more. Finally he realized that he just couldn’t reach it, and gave up. He called Charley, but Charley sat with his eyes on the squirrel and refused to leave it. Joey couldn’t move him and presently went off, and then the dog gave up in his turn and ran away to hunt again.

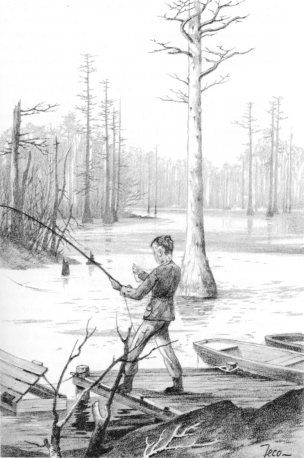

Their erratic course, during which Joey killed three squirrels with great expenditure of ammunition, took them the length of the Pond to the head of it where the country flattened out into a big swamp. The dark, slow branches of the stream that fed the Pond meandered through it and cypresses grew thickly in the water, many of them bearded with long gray streamers of Spanish moss. It was a dim and ghostly place, featureless and silent. Joey had never been into it, but as he skirted the edge and looked down the dim, watery aisles between the cypresses he determined to come back in the bateau and explore it. It was the wildest-looking place he had found so far; it looked as though no one had ever been in it, and he wanted to penetrate it and move about and see what was there.

The prospect was exciting, and as he thought about it he decided that he had killed enough squirrels for the day; besides, the afternoon was getting on and his mind turned toward the bass. He didn’t know where Charley was, but he whistled and yelled for him, waited a little while, and went back; when he reached the house the dog was waiting for him in the yard. Mr. Ben was on the porch, he had apparently been out on the Pond, seeing to his traps, and had three muskrats that he was skinning. “Any luck?” he asked.

“Yes, sir. I got three.” He watched as Mr. Ben made three careful cuts around the muskrat’s tail and working from them turned the animal’s skin inside out over its head without cutting again except for the legs. “Gosh,” he said. “Isn’t that something? Mr. Ben, how did Charley know I’d quit? I was up there calling him and he just came home.”

Mr. Ben got up and went and picked up a flat board, about as thick as a shingle and narrowed toward one end. He put the skin over this so that it was stretched a little, and hung the board up in the screened part of the porch for the skin to dry. “I don’t know how he figures it out,” he said, coming back and starting on another muskrat. He threw the skinned one to Charley. “Some people eat muskrats,” he went on, “but I’m not hungry enough yet. Maybe we’d better ask Sharbee how he knows. Charley I mean. I have to go see him pretty soon, and you can go along and ask him.”

“Who is Sharbee, Mr. Ben?”

“His name’s not really Sharbee. It’s Shaw B. Atkinson, but everybody calls him Sharbee. He’s an old black man who lives back in the woods, up the road a way. If anybody knows how an animal knows anything, Sharbee’s the one. You just wait and see.”

“Yes, sir. You reckon I have time to skin my squirrels before I go out on the Pond?”

“I think so.”

Joey took the squirrels out of his game pocket, picked one out, laid it on the porch, and took out his new belt knife. So far, so good; but he didn’t know what to do next. He turned the squirrel over and over, and finally, seeming to recall that one started to skin animals (with the exception of muskrats) by cutting a slit along the belly, made a tentative slice at it. The skin was tough and had apparently been put on the beast with glue; he hacked and sawed and made a mess of it. Finally, covered with blood, hair, and confusion, he looked up and found Mr. Ben quietly laughing at him.

“I’m not very good,” he said.

“Give me one of the others,” Mr. Ben said, “and watch.”

Mr. Ben took the squirrel and made a slit on each side of the tail and cut through the tailbone. Then he stood on the tail, and taking the squirrel by its hind legs gave a steady pull. The squirrel peeled out of its skin like a man peels out of a sweater, leaving only a little skin over the shoulder, head, and chest which Mr. Ben peeled off over its head. Then he gutted it. “A nice young one,” he said. “We can eat it for breakfast. Give me the other one and I’ll skin that. You better go fishing.”

“Yes, sir,” Joey said, and handed over the other squirrel. He had watched Mr. Ben’s expert performance with great interest and wanted to try it himself, but the sun was pretty well down. He went into the house, put his gun in the corner of the living room, and went into the bedroom and put his casting rod together and tied the frog to the end of the line. Suddenly, as soon as he had finished all this, he began to tremble. He was at last about to try the fish; everything was ready; now that the long-awaited moment had come he had an attack of buck fever. He was deathly afraid that he would do something wrong and ruin his chances to catch the bass for all time to come, and he wished that Bud was with him for support. When he realized he was wishing this he stopped trembling, and suddenly was ashamed of himself for his scheming and the way he had treated Bud.

These various emotions, coming all together, confused him; he laid the rod down on the bed and his face grew hot. For a moment he stood there indecisively, almost making up his mind not to go. He felt mean and sneaky and cheap, wanting to catch the fish and not to catch it. Tears came to his eyes and he rubbed them away angrily and said, “Gosh hang it!” Then he picked up the rod and ran out of the house, past Mr. Ben busy at his skinning, and down the path to the wharf.

He got into the bateau and cast loose and paddled across the Pond. The western shore on his right, one of the short sides, was deeply shadowed now by the hill behind it. The breeze had dropped with the sun, and the long length of the Pond, stretching away on his left, was still, without a ripple. He stopped paddling and cast the frog, jerking the rod tip a little to see if it would kick. It kicked perfectly, and he wound it in and put the rod back on the bottom of the bateau. He began paddling again; he felt that everything was right, but got no satisfaction from the feeling. It was not as he had anticipated it, at all.

When he got to the right distance from the cypresses he carefully swung the bateau, put the paddle down silently, stood up, and made his cast. It was perfect. He began to reel in, jerking the rod tip just enough. The frog had moved only six feet before there was an eruption of water so loud and spectacular in the silence that he jumped and almost lost his footing; he jerked the tip up and was fast to the bass.

A swift, wild thrill of triumph scorched through him, so intense that he forgot everything else, and then he was too busy to think for a while. The bass was crafty and full of power; it made one long blind rush, burst out of the water, shook its head savagely, and went to the bottom. Joey couldn’t move it; he was terrified that it had tangled him around a sunken tree. He had read somewhere that when a fish did that, the way to stir it up was to keep a tight line and tap smartly on the rod, so now he drew his belt knife and rapped on the rod repeatedly, and the shocks traveling down the line got the fish into motion again. It ran toward him and, having got some slack, surfaced and threw its head about to shake out the hook. Joey frantically wound in line, almost weeping with anxiety, until he got rid of the slack, and then played the fish until it was exhausted and came in belly side up beside the bateau.

It was a very large bass, and must have weighed between twelve and thirteen pounds. Joey had to lay down his rod and use both hands on the landing net; the bass filled the live box, and after he had got the hook out of its jaw he sat down and stared at it. He was shaking from the excitement and the fear of losing it that had been in him, and now that he had it safely in the box he felt deflated and empty; the emotions that had confused him in the bedroom descended upon him again. He thought of Bud and his own maneuverings, the page torn out of the catalogue, and his face grew hot with shame. He got up stiffly, like a boy retreating from a fight, measured the length and depth of the fish with the paddle and cut notches on the paddle handle with his belt knife; then he scooped up the fish in the net and dumped it over the side. He didn’t even watch it lie for a moment in the water and then swim wearily away. He sat down and dropped his head into his hands and drummed his feet on the bottom of the bateau and wept.

They had squirrels for dinner; they were young, tender, and sweet, and Mr. Ben showed Joey how to make lyonnaise potatoes. Joey was quiet and subdued, for the affair of the bass had worn him out. When he had returned from the Pond Mr. Ben had taken one look at him and asked no questions, and Joey hadn’t volunteered any information. He was grateful to Mr. Ben for not talking about it.

They picked the small squirrel bones and took care of the dishes in companionable silence and went back into the living room and sat down by the stove. Mr. Ben filled his pipe and lit it, got out a pad, an old pen, and a bottle of ink, and wrote Joey’s mother a letter in a fine copperplate hand. When he had sealed the letter he looked at Joey and saw him nodding in his chair. “Maybe you’d better go to bed,” he said. “You’re tired.”

Joey’s head came up. “It’ll be cold in there.”

“We’ll get you a brick,” Mr. Ben said. “I meant to get one for myself.” He went out and returned with two bricks, which he placed on the flat top of the stove. “Soon as they get hot enough we can turn in.”

“Yes, sir,” Joey said, and sat looking sleepily at the two bricks on the top of the stove. “You ever killed a turkey, Mr. Ben?”

“Why, I’ve killed a couple. But that Hosiah Burt, that your father bought the place from … gentlemen, sir, he used to slay ’em. He’d find out where they were using, and he’d go there and just stand still for hours if he had to and wait for them to come to where he was. He’d get up against a tree and never move his feet or much of anything else. He’d stand there and move his head slow, looking this way and that, and if they didn’t come his way that day, they’d do it the next or the day after that, or sooner or later. He practically turned into a tree, and that’s what it takes. A turkey’s got the sharpest eyes of anything; one little movement and they’re gone.”

“Yes, sir,” Joey said dutifully. Warm and half asleep, his drowsy mind pictured Hosiah Burt, who Mr. Ben had once said was a tall man with a beard, immobile as a statue flattened against an oak or a beech while a flock of turkeys fed through the woods toward him. Somehow Hosiah faded and Joey took his place; the beautiful birds, slim, wild, dark, gleaming with a shifting iridescence, came toward him scratching and pecking in the fallen leaves. One little movement, Joey knew, and they’d be gone, and he was still as a stone. They came closer, and then they were within range. An old gobbler, a great heavy bird with a long beard hanging from his chest, suddenly threw up his head suspiciously and Joey exploded into action. “Bang!” he shouted.

He and Mr. Ben both jumped in their chairs; both of them almost upset.

“Great day, boy,” Mr. Ben said, when they had righted themselves, “you took five years off my life.” He began to laugh. “I was talking about turkeys, and then …”

“I shot a big gobbler,” Joey said, shamefaced. “I reckon I was dreaming, Mr. Ben. I’m sorry I scared you.”

“I don’t mind being shot if you got him. There’s no eating like a turkey, and I haven’t had one for a long time.” He got up and went upstairs, and when he returned he had a little thin-sided box with him. He sat down and scraped the chalked lid of the box across the top of one of the sides. A series of short, clear, yelping sounds filled the room, and Joey’s hair stirred on his neck. He had heard domesticated turkeys make the same sounds, but this was wilder and more plaintive; it was a wild turkey itself. He stared at the box in fascination, and Mr. Ben said, “If you ever break up a bunch of turkeys, don’t run around and shoot just to be shooting. Don’t shoot unless you get one in range. If you don’t, keep quiet and come right back here and get me. When a bunch gets broken up they want to get together again, and they stand around and call. You get me, and we’ll go and see if we can call one up.”

“Yes, sir,” Joey said. “I sure will. Could I see the call, Mr. Ben?”

Mr. Bend handed it over. Joey was all thumbs with it, and couldn’t get a sound that had any resemblance to a turkey. Mr. Ben grinned at him. “Takes practice,” he said. “You can work on it now and then.” He took the box back and put it on the mantel behind the stove. “You’re too tired to be any good at it now.” He leaned over and spat on one of the bricks. It sizzled, and he nodded his head and got up and found an old newspaper in the kitchen cabinet and brought it back into the living room. He reached behind the stove and brought out a wooden instrument that looked like a big pair of pliers, picked up a brick with it, and, laying half the newspaper on the floor, put the brick on it and wrapped it up. “There, now,” he said. “Go and put that in your bed and jump in after it.”

Joey remembered the sizzle. “Won’t the paper burn?” he asked. “It’s awful hot.”

“It probably will be scorched brown by morning, but it won’t burn. I’ve been doing it for years.”

Joey picked up the brick. It was so hot that he had to run into the bedroom with it. He put it into the bed, came back, and undressed and put his flannel pajamas on. “Good night, Mr. Ben,” he said.

“Pleasant dreams. Oh, I almost forgot. Odie and Claude want you to go coon hunting tomorrow night. Want to go?”

“Yes, sir,” Joey said, and went back to the bedroom again and crawled into bed. The brick was wonderfully comforting; he pushed it around with his feet until all the cold, dank places were warm, and then brought it back to within a few inches of his stomach. It was like a little stove, and as drowsiness overtook him he thought of the turkeys again and then the bass; but this time it was something that had happened long ago, and somehow the meanness had been cleansed.