The day dawned clear and a little warmer, and there was a boisterous northwest wind; it was roaring in the walnut trees when Joey went out on the back porch to brush his teeth and wash his face with cold water in the enamel basin. Because he hadn’t washed his face since he’d left home, he went all out and used a little soap; he felt phenomenally clean and glowing when he came back in again. Mr. Ben was busily scrambling eggs on the stove and had already cooked the bacon. He pointed to the loaf of bread on the table, and Joey cut a few slices and toasted them one at a time on a long fork over the rear eye of the stove from which Mr. Ben removed the lid.

“It’s not a very good day for squirrels,” Mr. Ben said, as they finished eating. “The wind’s making so much noise in the woods I doubt if Charley could hear them very far. He hasn’t showed up, anyhow. Maybe Sam took him off somewhere himself.”

“Yes, sir,” Joey said. Since he’d got up he’d been thinking about the head of the Pond again, and now he had a good reason to go there; he could take his gun along and still-hunt if he felt like it. He decided to go. “I reckon I’ll go up toward the head of the Pond in the bateau.”

“Keep your eyes open up there,” Mr. Ben said. “You might see some turkeys. If you want to go to Sharbee’s with me, you get back in the middle of the afternoon.”

“Yes, sir, I’d like to go.”

“Maybe you ought to take a couple of sandwiches, then you wouldn’t have to come back so soon.”

“Yes, sir,” Joey said, and set about making two sandwiches from canned corned beef. He put them into an old paper bag, got his gun and fishing gear together, and went down to the wharf. The water was rough in the wind, with a running glitter of sun on it, but Joey stayed under the lee of the northern shore and had no trouble. The trees were tossing about in the woods; it was a crisp, cool day of low humidity, with a high, clear sky, that brings a feeling of well-being with it, and Joey sang to himself as he paddled up the shore. He didn’t fish; there was enough wind under the lee of the shore to swing the bateau around if he left it to its own devices, and he saw nothing to shoot at. When he reached the head of the Pond he hugged the east shore and turned into the mouth of the stream. He was among the cypresses, and as the swamp was low and under the wind, the silence of the place settled around him.

He didn’t have to get very far in before the strange, brooding quality of his surroundings took hold of him; among the close-growing cypresses, gliding over the dark, still water was like being in another and different world. He paddled slowly and silently, listening, not wanting to break it; it seemed to him that he had left the Pond and its familiar, everyday creatures behind him, and that at any moment some unknown creature, unknown and unguessed at, would appear. He followed the winding water farther and farther into the swamp, hearing nothing but the drip from the paddle as he brought it forward and the whisper of blood in his ears.

There was more Spanish moss now, hanging gray and ghostlike from the trees and reflected on the water; no other plant in the world would have been so fitting for such a place. The feeling of almost penetrating the mystery, more intense here than in the sunny woods with Charley, had come upon him again, and at one point he wished that he could stay here forever. He had lost track of time but his subconscious was aware of the tyranny of it; finally he decided reluctantly that he would have to turn back.

He let the bateau lose its forward way and moved to the other end of it. Now that he faced in the opposite direction he realized at once that he didn’t know the way out; the waterway that had seemed so easy to follow in its winding course was now only one of several, and there was nothing to distinguish between them in all the water around him. At first he thought only that he would be late to go with Mr. Ben to see Sharbee, and then he knew he might be much later than that. The neighboring Dismal Swamp was well fixed in local legend, and now he remembered stories he had heard of men who had got lost in its gloomy recesses and never got out again, of torchlight hunts for them finally given up. He had forgotten to keep the bow of the bateau steady, and now he realized, as he watched a cypress in front of him, that it was turning slowly; he didn’t even know any more in which general direction he should be heading. The surrounding swamp, so fascinating in its difference a few minutes ago, had become a prison that held him with a remote and inimical detachment.

The strange blind panic that takes hold of people lost in the woods and makes them run in circles took hold of him, but here, surrounded by dark water and cypresses, he couldn’t run; he couldn’t engage in the violent physical action that releases the tension of the nerves and leaves the lost one sweating and exhausted but calm enough to think a little. Any violent action here would have him ramming into the trees or capsizing the bateau.

He had a few bad minutes in which panic ruled him so completely that he didn’t think of anything, but he was not given to hysterics and presently the panic began to subside. He came out of it sweating and trembling but sensible again, and assayed the situation. At best he would have to stay here until he was missed, probably at the onset of darkness, and Mr. Ben came looking for him; then a few gunshots between them would give his location and the location of his rescuer; gunshots, or even shouts, carried well around the Pond where it was so quiet. It occurred to him then that this water was flowing into the Pond, just as it was flowing out over the spillway; there must be a current, a small current but a definite one. He was excited by this thought and rather proud of himself for having it, and suddenly very hungry. He got out the sandwiches, tore off a small piece of the bag and put it in the water, and began to eat. He watched the floating paper. It moved very slowly, but it moved; by the time he had finished the first sandwich he had some idea of the direction he should be going. If there had been any wind the paper wouldn’t have been much use to him, and he realized that.

He wondered what he would have done if there had been any wind, and thought of the sun; but it was the middle of the day and the sun was overhead. He would have to wait for afternoon to use the sun. He didn’t intend to wait that long if he didn’t have to, but it was a lesson to him. He hadn’tthought of being lost before or bothering about direction, but now it would be a part of his thinking.

He waited until the paper was almost out of sight, and caught up with it and waited until it was almost out of sight again. Presently it became waterlogged and sank and he put a new piece of paper overboard, and so, by very slow stages, he came through the swamp into view of the Pond again.

He had a great feeling of triumph when he saw the open water; he wasn’t quite the same boy who had gone so heedlessly into the swamp. He was aware that he had learned something and had had a minor victory, and was very pleased. He looked back into the swamp and knew that he would go into it again and again without fear, for it was a special place to him now, and he picked up the paddle to go back to the wharf.

Before he took a stroke his eye caught a movement at the edge of the stream near the Pond, and he held the paddle motionless and watched it. There was some creature in the water; moving at the apex of a ripple it turned in and came toward him. It rolled and dove and surfaced again, frequently changing direction, seeming to play, moving with such a fluid grace that it fascinated him. It came closer, until he could make out the rather flat head and broad whiskered muzzle. Then it saw him; it stopped, looked at him for an instant, and dove so smoothly that it scarcely disturbed the water. A line of small bubbles appeared as it swam underwater past the bateau and he didn’t see it again. He was sorry that it had gone; it had been the most beautiful thing in motion that he had ever looked at. He realized belatedly that he could have shot it, but he didn’t have any regret; he was glad that he hadn’t. It had been so beautiful in action that it had been more fun to watch than to kill.

Back at the house again he found Mr. Ben waiting for him, and told about the creature he had seen. “It was so smooth and slick it hardly even made a ripple,” he concluded. “You reckon it was a muskrat, Mr. Ben?”

“It must have been an otter,” Mr. Ben said. “A muskrat has a pointed face and isn’t that pretty to watch. Otters are the prettiest swimmers of all, even prettier than seals. They’re hard citizens when they’re pushed, too. They’re rough fighters. I didn’t know there were any around; they’re rare. They’re worth twenty dollars. I’ll have to see if I can trap him.”

“Yes, sir,” Joey said, but he wasn’t sure he wanted the otter trapped. “Twenty dollars is a lot of money, but he sure was pretty.” Then he added, “Maybe you can catch him when I’m not here.”

“I’ll wait. Put your rod and gun away, and we’ll go along.”

When they had walked along the road a way Joey asked, “What are we going to Sharbee’s for, Mr. Ben?”

“I want to get some fox bait from him. He mixes up a mess of stuff that stinks like the Devil, but you put a drop or two around a trap and a fox is just bound to come in and roll in it. It works on them the same way catnip works on cats. I don’t know how Sharbee figured it out. Maybe a fox told him about it.”

Joey grinned. “Maybe he’ll tell me a few fox words.”

“Some people around here think he really could,” Mr. Ben said. “He’s the greatest hand with the varmints I ever saw, but he doesn’t say much. I think he’s more at home with animals than with people.”

Joey tried to picture the man in his mind, but he wouldn’t come clear; he was too foreign to the boy’s experience. He remained faceless and indefinite as they walked up the road.

After they had gone about a mile and a half, Mr. Ben turned off the road into a path through the woods, which they followed until they came to a small, unpainted, weathered cabin in a little clearing.

“Don’t talk too much,” Mr. Ben said as they approached it. “Sharbee’s shy, even with me.”

He knocked at the weatherbeaten door, which was hung on strips of dried leather for hinges, and a black man of medium height opened it. He was rather slight, with regular, almost aquiline features, as though some Arab strain far back in his ancestry still persisted. The irises of his eyes were pale, nearly amber, like a wild creature’s, and there was the air of a wild creature about him; he seemed ready to retreat to a place of safe concealment and watch from there. Joey found him strange and a little disturbing.

“Morning, Sharbee,” Mr. Ben said. “This is Joey. He’s staying with me, and I brought him along.”

“Mawnin’, Mr. Ben,” Sharbee said in a soft voice and ducked his head slightly to acknowledge Joey. “Y’all come in?”

“We’ll come in for a minute, thank you.”

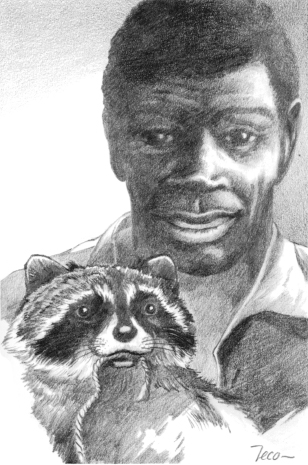

Sharbee stood aside, and Joey followed Mr. Ben in. There were two rooms in the little house; from the one they were in, which held a wood stove, an old table, and three decrepit chairs, which crowded it, Joey got a quick impression of a pitiful bareness, unpainted and as weathered as the outside. Everything had a worn cleanliness, but Joey was not accustomed to such an air of poverty. He was a little startled, but tried not to show it or to stare. They all sat down, and before a word was said, two cottontail rabbits hopped out of the other room, stopped under Sharbee’s chair, and became very still. Joey knew enough about wild rabbits to know that no one he had ever heard of had managed to tame one of them, even when they were taken from the nest before their eyes were open. He was still thinking about this impressive fact when he realized that a raccoon, with its little black highwayman’s mask, was peering at him around the corner of the door.

He had seen a tame raccoon once, from a distance, and had always longed for one; he didn’t know whether to make a gesture toward it or to sit very still.

“Y’all be quiet,” Sharbee said, as though he knew what the boy was thinking, “he come in.” He turned to Mr. Ben. “I reckon you came for the fox bait,” he said. “I got it all made up. I get it presently.” He made a chirping sound, and the raccoon ambled into the room and stopped in front of the boy.

It looked him over carefully, glanced at Sharbee, and climbed into Joey’s lap; it sat there peering questioningly into Joey’s face with its black eyes. It was such an engaging little beast and seemed so intelligent in its regard that Joey’s heart went out to it. He forgot the tales of raccoon ferocity in fights with dogs that he’d heard from his father’s coon-hunting friends; he smiled at it. The raccoon began to make a low, chuckling sound; it climbed up his arm to his shoulder, thrust its sharp little nose into his ear, and made a series of soft little puffs that tickled. Joey felt its small hands feeling around his ear and examining his hair, very deftly and softly. He couldn’t resist any longer; he raised one hand and lightly stroked its fur. The raccoon was very still for a moment; Sharbee chirped again; then the raccoon climbed down Joey’s arm, sat in his lap once more, and began to play with one of the buttons on his shirt. It was still chuckling.

“He like you,” Sharbee said, in his soft voice. “Most people pat him, he liable to bite.”

Joey cupped his hands around the animal in his lap. It was soft and warm, its busy little paws were like hands, and its dark eyes seemed friendly and full of mischief; he loved it. It was not at all what he had thought a wild animal would be like, and suddenly he wanted it very badly. “I’d sure like to have it,” he said, looking at Sharbee, and then added in a rush, “You reckon you could sell it?”

“No, sir,” Sharbee said. “I don’t reckon I could.”

“Please sell it,” Joey said. “I’ve got ten dollars saved up, and my father would give me more.” He looked at Sharbee beseechingly, entreating him; he had never wanted anything so much.

Sharbee looked at him with his odd, amber eyes, glanced quickly around the bare room, and dropped his glance to the floor. “No, sir,” he said softly. “I don’t reckon I could.”

Joey was about to speak again, to offer more money; he didn’t know where he’d get it, but he’d get it somehow. He opened his mouth to speak, but Mr. Ben forestalled him.

“Joey,” Mr. Ben said, and having got Joey’s attention, shook his head.

“Yes, sir,” Joey mumbled, and a feeling of loss, of desolation, washed over him. The raccoon suddenly ceased playing with his shirt button, looked at him with its head cocked slightly, and then climbed up to his shirt pocket and began to feel around in it with one paw, chuckling. This gesture made him want the creature so much more that it almost brought him to the point of tears. He couldn’t stay there; he picked the raccoon up, placed it gently on the floor, and went outside. He walked a little way down the path and stopped; as he stood there a feeling of protest welled up in him and the woods around him blurred a little on his sight.

He leaned against a tree and got control of himself. He was suddenly aware of his tears and then ashamed of them and wiped them roughly away, but his longing for the raccoon was undiminished. He had to have it, and Mr. Ben would have to help him. When the old man came along the path he fell in beside him. “Mr. Ben,” he said. “Mr. Ben?”

“Yes, Joey?”

“Mr. Ben, he has rabbits and everything, and he could get another coon. Why couldn’t he, Mr. Ben?”

Mr. Ben walked a few steps without saying anything. “I guess,” he said, finally, “that he loves that one. He’s pretty lonesome there alone, and poor, and not many people like him. They’re a little afraid of him, maybe, because he does things they can’t do, and because he’s different.”

“He could love another one,” Joey said, “just as easy. If you went back and said I’d give him thirty dollars …”

“We won’t do anything like that,” Mr. Ben said. “Thirty dollars would seem like all the money in the world to him, and it wouldn’t be fair. I won’t let you tempt him like that. You’ve got so much and he’s got nothing but that coon, and I won’t be a party to getting it away from him.”

Joey stopped, and Mr. Ben stopped with him. “But I want it,” Joey said, and tears of frustration threatened him again. He was angered by this; it made him feel like a wailing child, and to cover this feeling he became a little defiant. “If you won’t help me,” he said, “I’ll bring my father here and he’ll get it for me.”

Mr. Ben stood there quietly looking at him, and under the old man’s steady regard the defiance leaked out of Joey as air leaks out of a punctured balloon. He stared back at Mr. Ben for a moment and then dropped his glance; in another moment he began to squirm. The things that Mr. Ben had said, the things he had heard and ignored, came back to him now; he began to realize what Mr. Ben had meant about Sharbee having nothing in his poverty and himself having so much. He realized dimly, and for the first time, that there should be an obligation upon the fortunate of this earth. He was ashamed, and when he recalled how the old man had let him go his own way he was more ashamed still. He stared at the ground and dug into it with the toe of one shoe. He still wanted the raccoon passionately, but he knew now that he couldn’t have it and why. He looked up. “I’m sorry,” he said.

“That’s better,” Mr. Ben said, and they started to walk again. After a few steps Mr. Ben said, “I’ll ask him to get you a little one in the spring.”

“Yes, sir. Thank you, Mr. Ben. I reckon I was sort of mean, wasn’t I?”

“A little one would be better. That one grew up with Sharbee; it would want to go back to him after a while.”

“Yes, sir. I didn’t have to be as mean as that.”

“I know how much you wanted it,” Mr. Ben said. “We all want things a lot sometimes, and it twists us around a little.”

“Yes, sir,” Joey said. He almost told Mr. Ben about the bass, and decided not to; that, on top of the raccoon, wasn’t very pleasant to think about. He looked at the old man. Lantern-jawed, stooped a little, and with a three days’ growth of beard, he wasn’t a very heroic figure to the casual eye, but to Joey he had emerged considerably enlarged from the fracas just finished. Mr. Ben turned his head and looked at him; Joey smiled, and Mr. Ben smiled back. They were friends again, better friends than before, and there was a very pleasant feeling between them as they walked down the road.

After they had finished their dinner and washed the dishes Joey remembered that Odie and Claude were coming to take him coon hunting. He had never been coon hunting, and the prospect was exciting—so exciting that it didn’t occur to him that the object of the hunt was to kill the cousins of the creature that had so enthralled him only a few hours before. In his mind they were, in fact, different animals; Sharbee’s raccoon, which lived in a house, was set apart from the feral creatures of the woods. Wild things were to shoot and tame ones were to cherish, and that was the way it was.

He had taken off his hunting shoes when he got back to the house, and now he put them on again. He got out his heavy sweater, gloves, and the hat with eartabs on it and laid them on the table, and then waited impatiently. Time crawled by; it seemed as though the two boys were never coming.

“Mr. Ben,” he said, “you reckon they’ve forgotten?”

“I doubt it. Probably Sam found something for them to do. He usually does.”

More time went by and Joey wandered aimlessly about; he had almost given them up when he heard their footsteps on the porch and they came into the kitchen. Odie was carrying a lantern and Claude an ax, they were wrapped up in a weird collection of threadbare sweaters, old coats, and jackets, and both of them had stocking caps pulled down around their ears. Their eyes went first to the kitchen table and found it empty; they looked with a quick disappointment at one another and then at Joey, trying to hide their regret.

“I’m sorry there isn’t any cake,” Joey said, feeling as though he had let them down. “I couldn’t bring it on the train.”

A constraint fell upon them all, for the two boys were embarrassed that their hopes had been so noticeable and Joey realized that he had blundered badly; he had hurt a pride that he hadn’t known they had. He had looked forward to going with them; he had missed Bud as another boy to go around with, although he hadn’t admitted it consciously to himself, and they would in a measure have taken Bud’s place. Now it was revealed to him that they were different, alien, and he had no key to the difference. He stood looking at them, not knowing what to say next.

“Don’t reckon we could handle it anyhow,” Claude said suddenly in his funny deep voice. “We had a pow’ful big supper.”

“Sure did.”

Joey wanted to ask them to help him bridge the gap he had created, but he didn’t know how; he gave up. “I reckon we’d better go,” he said. “I’ll put my things on.”

They watched him as he put his good warm clothes on and slipped his flashlight into his pocket, drawing together so that they could talk in their silent, nudging language, and then they all went outside. The wind of the day had dropped and the moon was out; it was cold and clear enough for a frost, and Charley was waiting patiently at the foot of the steps. Joey surreptitiously took two dog biscuits out of the can on the porch and slipped them into a pocket; after they had passed the gate he lagged behind a little and dropped one of them, which the dog picked up and ran off into the field to eat.

They turned west off the road before they reached White’s lane and were soon in the woods; presently they came to an old road and followed it. It was narrow, growing into brush, and drifted with leaves; trees stood closely on either side of them, and the bobbing lantern held them in a wavering, coppery circle as they walked. It brought into being a mysterious, limited world, edged with great black sliding shadows and flickering points of light. Charley had disappeared; the two White boys tramped silently along and Joey could find nothing to say to them.

He wished that he could somehow break down the wall that had so suddenly erected itself between them in the kitchen, for he wanted to feel close enough to them to enjoy hunting with them occasionally; he didn’t want to hunt all the time by himself, and he knew that he wouldn’t enjoy being with them if he always felt like an outsider, as he did now.

As he walked along a step or two behind them, thinking of this, the boys stopped and pushed up their stocking caps; he stopped and pushed up the eartabs on his own. The rolling voice of Charley came to them, mellowed by distance, and they all pulled down their caps again and began to run. They scuttled wildly through the dark woods, stumbling and whipped by branches, until they arrived scratched and blown at the base of a gum tree which the dog was circling with his muzzle in the air. Joey noticed, without really thinking about it, that the dog moved away when either of the boys came near it; staying out of their kicking range was a reflex action with it. He bayed once more and the White boys suddenly began to whoop and dance about. Claude put down the lantern and turned to Joey.

“Shine him!” he shouted. “Shine him!”

Joey didn’t know what he meant. He looked up the tree and could see nothing; the lantern’s light didn’t carry upward very far, and all was blackness and moonshine above him.

“Goddamn, shine him!” Claude whooped.

“Shine him! Shine him!” Odie shouted. “Goddamn!”

Joey stared at them, stunned by the uproar; the suddenness with which they had been informed by a noisy and riotous energy baffled him. They ran up to him, and patted his pockets.

“The frawglight!” they screeched at him. “Shine him with the frawglight! Goddamn!”

At last he saw what they meant, fumbled in his pocket, found the flashlight, and pointed it upward. The bright beam cut across the gloom; it wandered about and settled on a ghostly white shape, clinging to a limb and looking down at them. Its eyes glittered pinkly in the light.

“Whooee! We got him. We got him!”

The uproar ceased as suddenly as it had begun, and Odie said into the silence, “You git him.”

There was another silence; the two White boys stared at one another, and Joey said, “It’s not a coon, is it? It doesn’t look like a coon.”

“Possum,” Odie said, and turned back to his brother. “Go git him. Hurry up.”

“I’m scairt, Odie,” Claude said.

“You git him, or I’ll bop you,” Odie said, and moved toward his brother. Claude fell back a few steps and Odie went after him; while Joey watched, puzzled and uncomprehending, the larger boy suddenly jumped at the other and gave him a punch that knocked him off his feet. He stood over him and drew back one foot to kick; the other scrambled up off the ground and ran to the base of the tree. Joey could see that he was crying now, and then Odie went up to him and hit him again.

Claude cried out in pain, and started to swarm up the trunk of the tree. He reached the lower branches and began to climb, and Joey, still appalled at what he had seen, tried to help him with the light. The boy reached the limb that had the possum on it, carefully stood up, and holding a branch above him with both hands inched out toward it. The possum grinned at him, showing sharp white teeth, and retreated toward the end of the limb.

Odie raised his voice again, shouting, “G’on out! G’on out and shake him!”

Claude inched farther out, and began to move up and down. The limb rose and fell with an accelerating rhythm; the possum started back toward him, changed its mind, and scrambled back out again. It almost fell off several times. Claude increased his efforts and Odie whooped like a lunatic and the limb gave an ominous crack. Claude’s face was white and frightened in the darting light, and Joey’s stomach crawled with apprehension for him.

The limb let go; Claude hung by his hands and managed to get back to the tree trunk. Charley seized the fallen possum with a snarl, shook it several times, and began to run around the tree with the whooping Odie after him. Claude appeared in the lantern light as though he had got down the tree by magic. They both ran after the dog and fell on him; Claude picked him up roughly by the tail, and Odie snatched the possum out of his mouth by its tail. He held the possum head down, with its head on the ground, and Claude picked up the ax, laid its handle across the possum’s neck, and stood on each side of the handle. Odie gave a mighty upward heave; there was a sharp ugly crack as the possum’s neck broke, and both boys whooped again. They looked like a pair of bedraggled minor devils at some horrid rite.

Claude stepped off the ax handle and the possum slowly rolled over as it died, grinning. The two boys stood looking down at it and became still. All of the wild energy had gone out of them, and in the coppery light their faces were a little drawn, tired and empty; their shoulders slumped and Claude’s face was smeared where he had wiped the tears off it with his dirty hands.

Joey stood in the background, staring at them in their sudden transformation and still hearing, like an echo inside his skull, the crack of the possum’s backbone. That chilling sound, the crazy kaleidoscopic scene in the flickering light, the whooping, and Odie’s sadistic thumping of his smaller brother showed him that he could never get together with them now. It was not only the incident of the cake that separated him from them; it was an entirely different way of life. The tensions that had been built up in them by their father and their lives which required the kind of outlet he had just seen were completely beyond his experience.

Odie turned to Claude. “Pick it up,” he said. “We got to go home.”