It was late in the afternoon when Joey awoke, and the house was very quiet. Charley wasn’t in the room, and Joey thought that probably Mr. Ben had let him out and he had gone home. He had a dim recollection of the dog close beside him as he came into the house, and that pleased him; they were really friends, and wouldn’t have been if there had never been a fight. He lay there still a little drowsy, listening for Mr. Ben’s footfalls, but could hear nothing; probably the old man had gone out to see to his traps. He remembered them sitting on the back steps looking at the dead bobcat, slab-sided and collapsed-looking with the breath of life gone out of it, so different from itself when it had been pouncing about with a demoniacal expression in its agate eyes, full of vitality. What if it had found the otter in a trap, fast and encumbered and helpless, as the hawk had found him when he lay half stunned after he had fallen through the blow-down?

As he thought of this, of the hawk’s impersonal but pitiless eyes, he shuddered; no creature was ever free from the shadow of a violent death. Yet they didn’t dwell upon it; they went calmly about their lives and played happily when the mood was on them, like the two little flying squirrels in the dusk between the flights of hunting owls or the solitary old raccoon with the light-colored stone. The raccoon knew that there was nothing under that stone, and had known it for a long time.

As these things drifted through his mind he felt very close to the animals he had watched; not hating any of them any more took away the last barrier between them and himself. He wanted to know more about them, to share—if only as an observer—in their lives. They were as interesting and varied (and much less complicated and unaccountable) as people, and made no demands upon him. He wasn’t ready for the demands of people yet.

His mind drifted back to the fight and the things it had brought him: Charley’s trust, and the long hunt and the things that had come of it. Why, after all his plans and the long wait, when he had his enemy the otter under his gun, hadn’t he shot it instead of the hungry cat? Perhaps he should feel as though he had done a silly thing, and yet he didn’t; he felt light and free, as though the thing he had done was right. Besides, he had been a hunter, and now there was an intimation of a reluctance to hunt in him; it was a puzzling and disturbing thing.

His forehead creased as he searched for a clue to these riddles, and presently he dozed again. When he awoke it was a little past twilight, and the room was growing dark. There still wasn’t a sound in the house. He got up and walked through the living room into the kitchen, but they were dark too; Mr. Ben wasn’t about. He lit two lamps, shook up both stoves, and put more wood into them, for the house was getting cold. Mr. Ben had never been this late at his traps, and Joey began to worry about him. He wandered around the house, wondering what he ought to do; he had almost come to the decision to go down to the wharf with his flashlight and take out one of the other boats when he heard footsteps on the porch and ran into the kitchen. Mr. Ben was just coming in the back door and grinned at him.

“Turkeys!” he said. “I roosted some turkeys up near the cut-over!” He was in high spirits and thumped the three muskrats he was carrying down on the table. “Must be eight or ten of ’em. This time I bet we’ll eat turkey.”

For a moment Joey was cross at Mr. Ben for worrying him, but his relief was so great and the news so exciting that he quickly got over it. “Great day!” he said. “Eight or ten? Are they close to the water? Can I take my gun this—”

“They’re not close enough,” Mr. Ben said. “We’ll have to wait until they fly down and call them. Let’s get our dinner started. I could eat a bear.” He took off his coat and sweater and put the frying pan on the stove. “Open some of that canned hash,” he said, bustling around. “I’ll get the potatoes sliced up.” He sliced the potatoes while Joey opened the cans, dumped everything into the pan, and began to stir it around. “Gentlemen, sir,” he said, “the air was full of turkeys. It looked like bargain day.”

“I thought something had happened to you,” Joey said. “I was about to come and see. I never thought of turkeys. What will we do, Mr. Ben?”

“We’ll get up early and go back to the cut-over and hide, and when we hear them fly down we’ll call. Hand me the plates.”

Joey handed him the plates; he filled them and they took them to the table. They were both hungry and attacked their dinner, but as Joey ate he imagined the procedure as Mr. Ben had sketchily outlined it: the hiding and waiting in the dark, daybreak, the uncertainty and suspense. The more he pictured it the more exciting it became. He could hardly wait to finish his dinner; when the last mouthful was gone he went into the bedroom and brought back the new call. Looking at Mr. Ben he pushed the plunger down, and the faultless, yelping note filled the room. They grinned happily at each other.

“That’s it,” Mr. Ben said. “You couldn’t do it better if you had feathers on. That old man knew his business.” He stood up. “We’ll wash the dishes, and then you better head for bed. I’ve got to skin those rats, but I won’t be long behind you. As long as you’ve already got the clock, set it for four and wake me up.”

“Yes, sir,” Joey said, and got up to take out his own plate. He had forgotten for the time the questions that had puzzled him; he was impatient for morning to come. He was afraid that he wouldn’t be able to get to sleep, but five minutes after he had climbed into the cold bed he was dead to the world.

The morning was cold, and this was its coldest hour; there was heavy frost on the ground and the stars glittered frostily. Joey pulled his head down into his collar and watched the vapor of his breath float sluggishly upward. They were only at the wharf, and he was shivering already.

“Holy Lazarus!” Mr. Ben said, untangling the old trap chain that held the bateau. “I wish I could light the stove. Talk about Greenland’s icy mountains …”

As it had before, the chilling mist was trailing languidly over the water, and they climbed aboard the bateau and shoved off into it. For a while their progress was as cheerless as passage in Charon’s ferry across the gloomy Styx, but after a bit their exertions warmed them and their eyes grew accustomed to the darkness. Two ducks that had been sleeping on the water got up quacking and pattering across the surface, but they couldn’t see them; they were only disembodied and temporary distractions in the mist. Soon after that Mr. Ben swung the bateau, and presently they reached the other shore. Joey crawled over the bow and carried the old sashweight the length of its rope, laid it carefully on the ground, and waited for Mr. Ben to join him.

It seemed to him that they walked for miles through the frosted brush, working their way around old treetops that reached out like monstrous spiders; unseen briers came out of nowhere and raked and clung to them. Mr. Ben finally found a place that suited him. It was below the top of a little rise and, so far as Joey could see in the gloom, gave them a downhill view into a small, fairly flat and open grassy clearing. After they smoothed out a sitting place and removed everything that might crackle, Mr. Ben went off and returned with an armload of brush to which dead leaves still clung and arranged it as a low blind in front of them.

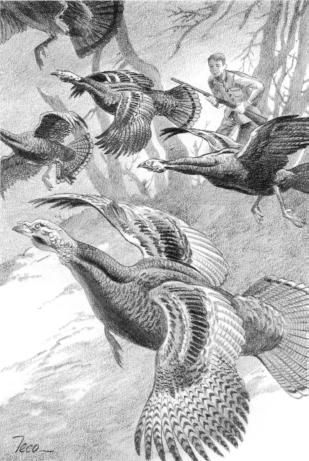

They sat down to wait. Joey could feel Mr. Ben shivering against him, and shivered in return. Dawn stole into the sky and Joey got his call out; the world about them slowly emerged from night. The woods at the edge of the cut-over grew clearer, and the frost sparkled on the brush on the higher spots as the first sunlight touched it; presently they heard the dry rattle of stiff feathers on branches as the turkeys began to launch themselves and fly down. Joey had been shivering with cold; he shivered harder now with excitement and anticipation. His hand tightened on the call, and Mr. Ben whispered, “Not yet.”

An age went by, and there was an end to the flapping; the turkeys were all down. Mr. Ben’s restraining hand was on Joey’s arm. He waited a little longer, and then whispered, “Now. Three times.”

Joey was terrified that he would do it wrong, but the call worked perfectly. There was an answer off to the right. Before Joey could push the plunger again Mr. Ben’s hand was on his arm once more, gripping harder than Mr. Ben had intended. “Wait!” he whispered. “Wait!”

Joey was nearly frantic; he wanted to call at once, to talk to the turkey that had yelped and might even now be standing indecisive and ready to turn away, close at hand in the concealing brush. The hand gripped and held and finally fell away. “Once,” Mr. Ben whispered. “No more.”

Joey called once and put the call down and picked up his gun. He remembered this time, and laid his thumb on the safety; he wasn’t going to be caught that way again. He sat frozen, staring through the little opening in the brush piled before him. One moment the clearing was empty and the next there was a big gobbler in it, a materialized lean shape, black and touched with metallic iridescence, magnificently wild and beautiful with its snaky head high and darting quickly this way and that.

“Shoot him!” Mr. Ben breathed.

Joey jumped up and, holding on the turkey’s neck between its darting head and its body, fired both barrels at once. The recoil knocked him over backwards, but as he went he saw the turkey go down. He scrambled up and hurdled the brush; the turkey was flopping wildly about, and he ran after it. Another darted out of the brush in front of him and leaped up and flew over his head, and just as he fell on his turkey he heard Mr. Ben’s gun roar.

He was first back to the blind, and then Mr. Ben came in with his bird and dropped it beside Joey’s. They grinned triumphantly at each other; they laughed in their pleasure and shook hands.

“Great day!” Joey said. “Great thundering balls of fire! We did it, Mr. Ben! We did it!” He couldn’t stop talking; he was too full of his triumph over the wariest of creatures, of relief from the awful tension and suspense. “When I saw him out there … Great day! I bet my father will sure open his eyes. I bet I’ll never forget it, Mr. Ben.”

Mr. Ben put a hand on his shoulder. “I don’t think you ever will either,” he said. “Neither will I. You ought to write your father and ask him to bring that box of bicarbonate next time he comes.” He grinned again. “Well, the prayers of the righteous availeth much, that’s for sure. As one old turkey hunter to another, I salute you, and I’d admire to have you join me for breakfast.”

After a fine leisurely breakfast they gutted the turkeys and hung them on the screened porch where their impressive appearance would surely stun any casual passer-by. When they had finished this pleasant chore and were surveying their handiwork with great satisfaction, Charley trotted into the yard.

“Now, I take it, you’ll be off after squirrels,” Mr. Ben said.

“I don’t reckon I will,” Joey said, and after he had said it was surprised. It had popped out before he thought, but as he considered it he wasn’t sorry. Somehow, he didn’t want to kill squirrels, or any four-legged thing, any more; the desire was gone. For a moment he felt a curious regret, remembering the first ones and the fierce wild excitement of it, and then he was sure. “I just don’t want to do it,” he said. “It’s funny, Mr. Ben.”

“I don’t think it is,” the old man said. “You learn about yourself as you go, and,” he went on, taking a long look back into the past, “sometimes it takes too long.”

“Yes, sir,” Joey said, missing the regret in the old man’s voice. “I reckon you thought I’d never quit going up there.”

The old man smiled. “I didn’t mind.”

“I bet you did. Last night when you were so late I worried about you, and that was only once.”

“Well, we’re even now,” Mr. Ben said. “And if you’re not going after squirrels, what are you going to do with this day so auspiciously begun?”

“I don’t know,” Joey said. He felt a little lost, as though he had come to the end of something and was waiting for whatever was going to take its place to begin. He moved restlessly inside his clothes; Mr. Ben put a hand on his shoulder, and they turned away from the turkeys and walked out onto the open part of the porch. Charley came up the steps; he pushed his nose into Joey’s hand, Joey stroked him, got four biscuits from the can, and they all sat down on the steps together for a while as Charley ate the biscuits. “I don’t know what I’ll do,” Joey went on, resting his hand on the dog’s back. “I wish Bud was here.” He stared in front of him for a long moment. “When I was waiting up on the creek I sort of got to liking all the animals, Mr. Ben. Birds are different. I reckon I can still shoot birds sometimes, but … Maybe I’m like Sharbee. I reckon I’d just like to watch them and know all about them and everything.”

Mr. Ben nodded. “You could do it, boy,” he said. “There are more people all the time and things will get crowded, and the people will want to get away from it once in a while and go places where it’s quiet and the woods still grow and the varmints still live in them. They’re going to need somebody like you to tell them about it and help run it. You can learn a lot more in college and be ready when they need you.”

Joey hadn’t begun to think that far ahead and the idea was new to him, but it sounded fine; it sounded just like the thing he wanted to do. “Great day!” he said, as the beauty of it took hold of him. “You reckon I could? You reckon my father would think it was all right?”

“I’m sure he would.”

“I’ll sure ask him.”

“I’ll ask him too,” Mr. Ben said. “You’ve got the bulge on him now with that turkey, but I’ll put in my two cents anyhow.”

Joey turned to the old man who had been so good to him and a great glow of gratitude and affection filled his heart; his smile was a little tremulous. “Thank you, Mr. Ben,” he said, and afraid that he would show too much emotion quickly stood up. “I reckon I’ll go see Horace now. That’s what I’ll do. I never did take him the books I brought.”

Mr. Ben stood up too. “You do that,” he said. “Stop for the mail on the way, and give Horace my regards.”

“I will,” Joey said. He went into the house and got the books, and with Charley beside him went out the lane. He stopped at the mailbox and found a letter from his father in it. As he walked up the road he tore it open. It read:

Dear Joey:

I’m sorry, but I’ll have to cut your vacation short. Everything’s fixed about the skyrocket, and I have to go to New York for a week and your ma’s worried about having you so far away while I’m gone. Maybe I’ll be there to get you before you get this letter, or anyhow soon after you do. Maybe I’ll bring Bud and his cousin from Atlanta with me for company on the ride. You and I can come down again before the season’s over. I bought the setter.

Love,

Dad

He folded the letter and put it in his pocket, and for once was not too cast down by the prospect of leaving the Pond. The feeling of being at a loose end that had come upon him awhile ago made it not too much of a wrench this time, and he wanted to talk to his father about the future that Mr. Ben had suggested. Besides, his father said they could come a little later; they could hunt turkeys and bring the setter and hunt quail. All this sounded exciting, and his mind was busy with it as he turned off the road and walked up White’s lane. When he was nearly to the well, he dropped the books. One of them was Peter Pan in Kensington Gardens, and he had picked it out especially because he thought the wonderful Arthur Rackham illustrations would delight Horace for a long time. It fell on its spine, and one of the plates came out and the light wind carried it through the fence.

Not remembering, Joey climbed the fence and ran after it. In the middle of the enclosure he was suddenly aware of a queer high sound and the quick pounding of hooves and looked startled around to see the mule with its yellow teeth bared and its ears laid back coming for him. He turned to run and tripped himself and fell down. It was a terrible moment; he saw the running mule come swiftly closer and couldn’t seem to move, and cried out. The mule reared, between him and the sky, and a black shape leaped over him and Charley had the mule by the nose. The mule screamed and went back on its haunches, leaped sideways screaming, and ran around the enclosure shaking its great head, whipping the dog about. When it reached the fence it reared again, flailing at the dog with its front hooves. Joey was on his feet; he ran toward them, and his wild glance finding a piece of fence rail on the other side of the fence, he scrambled over the fence and grabbed the rail and beat at the mule with it. There was a confused shouting and Sam White appeared behind the mule with a pitchfork, which he jabbed into its rump. As the mule wheeled, one of its forefeet caught Charley in the head, and he fell beside Joey and lay still.

Joey was on his knees beside the dog; the mule swung away and White climbed the fence and knelt next to the boy. It was evident to Joey that one of Charley’s forelegs was broken; there was a shallow cut on his head and his eyes were closed, but he was breathing.

“Goddamn mule!” White said. “I wish to God I could afford to shoot him. You reckon that dog’s all right, outside of bein’ knocked out?”

“It looks like his leg was broken,” Joey said, stroking Charley’s side and wishing desperately that he would open his eyes.

“Goddamn mule. We wouldn’t eat much meat, wasn’t for that dog. I reckon I better tie his leg up.”

“Isn’t there a vet?” Joey asked. “If there’s a vet you ought to take him there.”

White looked at him. “I can’t afford no vet,” he said, in a flat tone. “Not for a dog.”

“My father would pay him,” Joey said. “Please take him to the vet, Mr. White. It was my fault. I forgot about the mule and went in there and it came after me, and if it hadn’t been for Charley …” He had been surprisingly calm until then, and suddenly he began to shake. “Please take him,” he pleaded. “My father will pay anything that it costs. Mr. Ben will tell you where to send the bill.”

White stared at him for a moment, his remote eyes intent for once. “I will, then,” he said finally. “You stay here with him while I get the machine.”

He stood up and hurried to the barn; soon he came down the lane in his old Model T. He stopped it and got out, and he and Joey picked Charley up and carried him over and laid him on the floor in back. Joey wanted to go along, he was anxious to see what the vet could do, but White wouldn’t have it. “I reckon you better not,” he said and drove off.

Joey stood watching him go. He was pale and still shaking from the fright he’d had, from the feeling of being in a nightmare with the mule rearing over him and unable to move, but he wasn’t thinking of that. His mind was on Charley, hurt and still with his eyes closed and his leg dangling; maybe he was going to die, or would always be lame. Joey couldn’t stand that thought; his fists clenched and his eyes blurred with tears.

“Joey,” a voice said. “Joey?”

Joey started and looked around. Horace had come up in his little wagon, steering with one hand and turning one of the rear wheels with the other; it had been hard work to get through the sandy soil, and sweat stood out on his bulging forehead. “You aren’t hurt, are you, Joey? I heard the sounds but my mother and Odie and Claude are out getting running cedar for the florists and there was nobody to push me. Are you all right?”

“I’m all right,” Joey said, wiping his eyes. “It was Charley. The mule hurt him, and your father took him to the vet.” He had stopped shaking now. “I was bringing you the books.”

“Is Charley hurt very much?”

“I don’t know,” Joey said. The books were still scattered where he had dropped them, and he gathered them up. “He has a broken leg, I think, and he was unconscious. Oh, Horace, I hope it’s not bad.”

“I hope it’s not too. I like him. Did you like him, Joey?”

“I wanted to be friends with him and he wouldn’t be, and then I helped him get away from the otter and then he was friends. He helped me get away from the mule.”

“Helped you?” Horace asked. “Joey, did you …?”

“I dropped the books and a page blew in there and I forgot and went after it. And then the mule came after me.”

“Oh, Joey,” Horace said. “Oh, Joey. Didn’t you know, didn’t they tell you?”

“Mr. Ben told me. He said your father … he said …” He stopped in confusion.

Horace looked at the ground. “Yes,” he said, in a low, shamed tone. “That’s right. Everybody knows it. And Charley too, and …” He shook his swollen head, and when he looked up his eyes were bright with tears. “I wish it hadn’t been you, or Charley.”

Joey was greatly moved by Horace’s tears, by the boy’s melancholy life and the things that his fate had prescribed for him; he was so moved that he wanted to get down on his knees and put his arms around Horace to comfort him, as one would comfort and defend a child against the frightening shadows that lay in wait in the world. He almost did it, and then the emotional moment passed; something within him, self-conscious and masculine, held him back. It confused him for a moment, bringing a brief regret. He looked at Horace, who seemed to realize what he was feeling; they gazed at one another with rueful smiles, and Joey put the books in the wagon.

“Thank you, Joey,” Horace said. “And thank you for the books.”

“I hope you like them, Horace,” Joey said. He felt that he should go, now. “Shall I pull you back?”

Horace nodded, and Joey pulled the little wagon back to the place where he had first seen the boy.

“Will you ask your father to let us know, when he gets back?” he asked.

Horace nodded again and smiled, that smile of surpassing sweetness that Joey still remembered from the time before.

“I’ll send more books,” Joey said. “Good-by.”

“I’m glad I know you, Joey,” the boy said. “I hope you’ll be happy in your life.” He smiled again, and bowed his head; much moved, Joey stole away.

Almost three hours later, as Joey and Mr. Ben were sitting on the steps, Sam White drove in. He didn’t get out of the Model T, and they walked over to the car.

“He come to on the way,” White said. “The vet said he reckoned he’d be all right. He put a thing on his leg, and he’s goin’ to keep him a few days.”

Joey felt almost lightheaded with relief; he had been dreadfully worried. “I sure am glad,” he said. “I was afraid he was going to die, or be lame.”

“Wouldn’t have been no account lame,” White said. “I told the vet that. I told him I ain’t about to feed a lame dog, but he said it would be all right.”

He moved back in the seat, as though to start off, and Joey moved forward. “If he’s lame,” he said, “if it isn’t all right, will you give him to me? I’ll keep him if he’s lame.”

White turned and gave him a puzzled look, as though such a thing was beyond the comprehension of a sensible man. “What for?” he asked, and as Joey recoiled a little added, “If you want to do it, okay. I got to get back.” He nodded, turned the Model T around, and drove around the corner of the house.

Mr. Ben looked at Joey and shook his head; they walked back to the steps again, and paused at the bottom step.

“Mr. Ben,” Joey said. “Mr. Ben?”

“Yes, Joey?”

“I’d like right well to have Charley anyhow, whether he’s lame or not. I’d be real good to him, and he wouldn’t be hungry or get hurt or anything. I sure wish I could have him, Mr. Ben. You reckon if my father went to Mr. White …”

Mr. Ben slowly shook his head. “Sam would never sell him,” he said, “as much as he could use the money. It might take him years to find another dog as useful to him, and he knows that. Besides, I’m not sure Charley would be happy in town, as much as he likes you. He has a sort of pride in his work; it’s part of him, and he wouldn’t be the same without it.”

“But, Mr. Ben—”

“He’d be like the Indians,” Mr. Ben said. “They had a pretty hard life, but it suited them. When it was taken away from them, even if they were made more comfortable, some of them sort of fell apart and got lazy and dirty and didn’t care any more.”

“Yes, sir,” Joey said sadly, and then brightened. “But he’ll be all right. The vet said he would.”

Mr. Ben nodded, and they said no more. Now that they knew Charley would recover, and that racking anxiety was gone, their great relief brought a lassitude upon both of them.

“I reckon I better go pack up,” Joey said presently. “My father sounded like he was in a hurry.”

“I’ll lend you a hand,” Mr. Ben said.

They climbed the porch steps and went through the house and into the bedroom and slowly began to get Joey’s things together. Into their mutual lassitude a gentle pensiveness had fallen, for they were going to miss each other. Presently Joey paused in his laggard efforts and looked at the old man’s bent head; a small lump came into his throat. “I reckon I’ve been pretty lucky to have a Pond,” he said, after he’d swallowed it, and then, “I sure thank you for everything, Mr. Ben.”

“You’re welcome, Joey,” Mr. Ben said, without looking up. “I think I should be the one to thank you. Don’t let it be too long before you come back again.”

Whatever Joey was going to reply was interrupted by the rattling arrival of a car in the yard. They both got up and went to the window. The Model T was just stopping. Joe Moncrief had already seen the turkeys; he pointed at them and opened the door and jumped out. Bud and a girl, a pretty, dark-haired girl of thirteen, appeared from around the other side of the car and ran to join Joe Moncrief; they all stood pressing their noses against the screen to see the turkeys hanging from the ceiling.

The girl, Bud’s cousin, was in the shadow of the porch roof now; Joey had seen her for only a moment in the sun as she ran around the car, but it seemed to him that he saw her the same way still. A special light, a nimbus, had gathered around her and glowed upon her and set her apart. Joey was confused. Something was happening to him that had never happened before, bringing with it a tingling lightness, at once melancholy and gay, that drew him to the girl within the nimbus and made him hesitate.

“Mr. Ben,” he said, turning to the old man. “She’s pretty, Mr. Ben.”

Mr. Ben had been watching him; Mr. Ben’s face held an odd little smile. “Ah, me,” he said. “There are new problems and discoveries every day, aren’t there? But this one will be more enduring than most.” He put his hand gently on Joey’s shoulder. “Come along, pilgrim,” he said. “We’d better go outside.”