2

2

2

2

The current climate of broken politics goes well beyond issues like the debt limit and spending. The problems are much deeper and broader, inside Congress, in the relations between Congress and the president, in campaigns, and in the coarsened, divided, and tribal political culture. But the problems did not emerge overnight. Some of their roots go back to major societal shifts in the 1960s; others are far more recent. But as we witnessed ourselves, none of the roots have been more important than developments set in motion in the election of 1978.

In 1978, the two of us formed an affiliation with the American Enterprise Institute (AEI) to create an entity we called “The Congress Project” to track Congress as an institution through an era of change. During the previous decade, both the House and Senate had undergone significant reforms in their internal rules and procedures, opening things up to more public scrutiny and to a role for more rank-and-file members as the seniority system was shaken. New-style members less tied to the status quo were elected, new politics were evident in campaigns and the country, and Congress was evolving in ways that demanded serious analysis.

We started the Congress Project in the midst of the 1978 midterm campaign—a seminal one, as it turned out. A group called the National Conservative Political Action Committee, or NCPAC, founded three years earlier by activists John Terry Dolan, Charles Black, and Roger Stone, emerged as a major force in the campaign, financing an independent spending campaign against liberal Democrats like Senators Dick Clark of Iowa and Tom McIntyre of New Hampshire. NCPAC produced a barrage of negative ads and passed out flyers at places like churches in an effort that ultimately brought down both candidates. One memorable flyer accused Clark, a supporter of abortion rights, of being a baby killer. By today’s standards, NCPAC’s campaigns were comparatively mild, but they were significant as the first example of what would soon become common on both ends of the political spectrum: nationalized, highly ideological, independent-expenditure campaigns.

Our first program at AEI recruited a small group of the freshman representatives that year to participate in regular, off-the-record dinners during their first term in the House. The idea was to allow them to talk candidly about their immersion in the legislative process and the political dynamics of the House. We sought members who would in some ways be representative of the body, but who also had potential, based on their backgrounds and campaigns, to be serious players in the years ahead. Among that group were Newt Gingrich, Dick Cheney, and Geraldine Ferraro. From the first session, it was Gingrich, a history professor at a small Georgia college who had twice run unsuccessfully for the House before he finally won, who stood out among the rest for his self-assurance and strategy, already fully articulated, for achieving a Republican majority in the House.1

Though he came to be viewed as a quintessential “movement conservative”—and that is the way he characterized himself during his 2012 presidential run—in those days Gingrich was much more flexible than ideologically rigid. He supported increased government funding in areas where he had a strong personal affinity, like science and health research. The Democrats had controlled the House that Gingrich entered for twenty-four years, and he believed that the great advantages conferred by incumbent status made a race-by-race approach to winning a majority for his party a losing one. How, Gingrich wondered, could the minority party overcome the seemingly paradoxical situation in which people hated the Congress but loved their own congressman?2 The strategy he settled on would bring him to power but have a devastating impact on the institution he ultimately led.

What was Gingrich’s strategy? He was both passionate about his goals and coldly analytical in his means. The core strategy was to destroy the institution in order to save it, to so intensify public hatred of Congress that voters would buy into the notion of the need for sweeping change and throw the majority bums out. His method? To unite his Republicans in refusing to cooperate with Democrats in committee and on the floor, while publicly attacking them as a permanent majority presiding over and benefiting from a thoroughly corrupt institution. Most of Gingrich’s colleagues in our dinner group, both Democrats and Republicans, were deeply unsettled by his description of that strategy, a sentiment many of his fellow Republicans shared over the next several years. One exception: Dick Cheney, an establishment Republican who quickly moved up in leadership ranks in the House, but who sympathized with Gingrich and his approach, and developed an enduring friendship with him.

After Ronald Reagan was elected president in 1980, the ranks of Gingrich’s insurgents were reinforced, opening the door for him to form the Conservative Opportunity Society (COS), an informal group of frustrated minority lawmakers. They set out to create an alternative power structure to that of Minority Leader Bob Michel of Illinois, who had worked well with his counterpart, Speaker Thomas P. O’Neill. COS was abetted by a Democratic majority that had grown complacent and arrogant. In a proto-insurgency movement, COS and its supporters used politically motivated amendments and overheated, hyperbolic rhetoric to poke and agitate Democratic leaders. They responded, as Gingrich anticipated, by overreacting, shutting off Republican amendments, and using or misusing the gavel to avoid embarrassing votes. Along the way, they radicalized even moderate Republicans who had been content to work within the system as minor partners.

Perhaps the seminal moment of this campaign of agitation came in the spring of 1984. In the back story, the House had a tradition of “special orders,” evening hours after the official business was done when members could reserve time to read speeches that would appear in the Congressional Record, even though they generally delivered them to an empty chamber. Usually, these speeches involved mundane and relatively unimportant things, such as allowing lawmakers to praise constituents. But the potential for political exploitation of evening hours changed markedly in March 1979, just three months after Gingrich took office, when C-SPAN launched its gavel-to-gavel coverage of House proceedings. Under House rules, cameras were put in fixed positions trained on speakers, with no camera operators panning the chamber. Ironically, the rules were intended to prevent political exploitation of the televised proceedings.

What Gingrich realized was that the fixed cameras meant C-SPAN viewers had no idea the speakers in the evening sessions were in fact addressing empty seats in the chamber. Although the C-SPAN audiences were not enormous, it was still an opportunity to reach the most politically involved voters. Gingrich and his allies began a regular process of reserving time in the evening, and a small group of lawmakers engaged in colloquies that attacked Democrats for opposing school prayer, being soft on Communism, and being corrupt. Gingrich called Democrats “blind to communism” and threatened to file charges against ten Democrats who had sent a warm letter to Nicaraguan leftist leader Daniel Ortega. In the favored technique, the lawmaker speaking turned as if he were addressing Democrats in the chamber, and the lack of response made it appear as if those in the audience either accepted the charges or were unwilling or unable to counter them.

This procedure went on for months, and in early May 1984, Speaker O’Neill decided it was time to retaliate by ordering C-SPAN cameras to pan the chamber during these special orders, showing the empty seats in the chamber. O’Neill also attacked Gingrich for impugning the patriotism of Democrats. On May 14, Gingrich took to the floor of the House and, with O’Neill in the chair, accused the Speaker not only of violating the rules, but of using words that came “all too close to resembling a McCarthyism of the Left.”

A Los Angeles Times reporter recounted what followed:

[T]he venerable Speaker exploded. “You deliberately stood in that well before an empty House, and challenged these people, and challenged their patriotism,” O’Neill thundered, “and it is the lowest thing that I’ve seen in my 32 years in Congress.” Gingrich’s predecessor as whip, Rep. Trent Lott (R-Miss.) immediately sprang from his seat. In the supposedly decorous House, members are barred from launching personal attacks against one another on the floor, a rule about which Gingrich had pirouetted with near-gymnastic skill. The presiding officer had no choice and ruled in Lott’s favor. The confrontation with O’Neill was big news, and Gingrich announced, “I am now a famous person.”3

That episode added to Democrats’ rage, which in turn led them to clamp down harder on Republicans, creating even more partisan hard feelings. The explosion with O’Neill was no accident. In a 1984 profile of Gingrich, a veteran reporter wrote:

I watched him [Gingrich] give a speech to a group of conservative activists. “The number one fact about the news media,” he told them, “is they love fights.” For months, he explained, he had been giving “organized, systematic, researched, one-hour lectures. Did CBS rush in and ask if they could tape one of my one-hour lectures? No. But the minute Tip O’Neill attacked me, he and I got 90 seconds at the close of all three network news shows. You have to give them confrontations. When you give them confrontations, you get attention; when you get attention, you can educate.”4

Gingrich wasn’t done. In 1988, he attacked O’Neill’s successor, Jim Wright, with a relentless barrage of ethics charges, mostly based on newspaper reports that Wright had improper associations with savings and loan officials and other business leaders. Initially, the House brushed the charges aside, until another event triggered a new populist explosion that put Wright and the majority Democrats in the House largely on the defensive. In 1989, members of Congress voted a substantial pay raise for themselves and other top officials. This vote was the result of a broad bipartisan leadership agreement, with support from outgoing President Reagan, incoming President George H. W. Bush, and congressional leaders of both parties, including Gingrich (who soon after Bush ascended to the presidency had been elected House Minority Whip to replace Dick Cheney). The result was a firestorm of criticism largely directed at the Democratic leadership and Speaker Wright, already tainted by the ethics charges. Although Gingrich had supported the pay raise, that fact did not stop him from turning on Wright and the Democrats, blaming the majority for the pay raise decision.

Shortly after the pay raise, the Democrats experienced the full fury of the populist reaction. Arriving in a group at Washington’s Union Station, bound for their annual party retreat at the Greenbrier, a resort in West Virginia, they were met by a crowd of protestors angrily denouncing the pay raise. Many House Democrats, feeling under siege, huddled together on the train ride blaming Wright, who they viewed as having done nothing to counter the attacks, for their plight. When the entourage arrived at the Greenbrier, they found network news reporters set up on the lawn, doing their stand-up reports from “the posh Greenbrier resort,” the worst possible image for embattled lawmakers.

Wright had lost support of his own party, and before the year was out, the House ethics committee charged him with a series of relatively minor offenses, including improper bulk sales of his book to interest groups seeking his favor. If in an earlier era the result would have been a reprimand, in this atmosphere there was no way Wright could stay as Speaker without irreparable damage to his party and the House. He resigned on May 31, 1989, further reinforcing the public’s image of Congress as corrupt. Wright’s farewell address from the House floor decried what he called the “mindless cannibalism” that had overtaken Congress, referring not so subtly to the campaign against him led by Newt Gingrich.

A new and vastly exaggerated media focus on a fat and perk-laden Congress filled with members living luxurious lives got new traction with a scandal in 1992 over the House bank. For many decades, the House had maintained an internal bank that deposited members’ paychecks temporarily until they were transferred to other accounts. Lawmakers could draw against their pay via House bank checks, and many had multiple overdrafts. Since the only money in the bank was from the pay of all lawmakers, the overdrafts were not misusing taxpayer money, but the idea that members of Congress could overdraw their accounts in ways that average voters could not caused further outrage. Ironically, that Gingrich himself had twenty-two overdrafts didn’t seem to matter.5

A group of Gingrich allies calling themselves the “Gang of Seven” seized on the bank scandal to take Gingrich’s confrontational tactics to new levels. Its ringleaders were Rick Santorum of Pennsylvania; John Boehner of Ohio, then only in his second year as a member; and Jim Nussle of Iowa. Their most memorable moment came when Nussle put a brown paper bag over his head while on the House floor, proclaiming that he was ashamed to be a member of Congress. The C-SPAN footage was repeated over and over on network newscasts. Gingrich’s goal of causing voters to feel enough disgust at the entire Congress that they would throw out the majority was within reach; he attained it a little more than two years later.

In 1992, the electorate, reacting to a poor economy, brought in a Democratic president for the first time in twelve years, with continuing Democratic majorities in both houses of Congress. This scenario was ideal for Gingrich, as it allowed him to capitalize on his party’s frustration at being out of power at both ends of Pennsylvania Avenue for the first time in twelve years; he was able to convince his party to vote en masse against major Clinton initiatives. Gingrich in effect convinced Republicans to act like a parliamentary minority; even in areas where some GOP members might have agreed with Democrats or wanted to bargain with them, they united in opposition, daring the majority to find votes only from within their own ranks. When Clinton could not keep the congressional Democrats united, it resulted in embarrassing and damaging policy delays and, on his signature health-care reform plan, spectacular failure, along with a deepening sense among voters of a broken political system. That sense was just what Gingrich and his allies wanted to cultivate.

As the 1994 midterm elections approached, Gingrich toured the country recruiting congressional candidates to run against incumbent Democrats and to pursue relentlessly the charge that Congress was corrupt and needed to be blown up to change things. He provided candidates with speeches and language echoing his own themes of rampant corruption in Washington and a House rotten to the core. This tactic included a memo that instructed them to use certain words when talking about the Democratic enemy: betray, bizarre, decay, anti-flag, anti-family, pathetic, lie, cheat, radical, sick, traitors, and more.6 It worked more spectacularly than he could have imagined. The midterm brought huge Republican gains—fifty-two seats—and its first majority in the House in forty years. Following the resignation of Republican Minority Leader Bob Michel, Gingrich, the Republican Whip and universally acknowledged heir apparent, was elected Speaker of the House. It had taken Gingrich sixteen years to realize his objective of a House Republican majority, but his original strategy to gain power by attacking his adversaries and delegitimizing the Congress left a lasting mark on American politics.

The seventy-three freshmen in the class of 1994, nearly a third of the Republican majority, were strong Gingrich loyalists who not only shared his disdain for Congress as an institution but believed it more deeply than he did, and who added their own conservative populist distrust of leaders and leadership. Freshman gadflies like Joe Scarborough of Florida, J. D. Hayworth of Arizona, Helen Chenoweth of Idaho, and Mark Neumann of Wisconsin were fiery and uncompromising. Scarborough and John Shadegg of Arizona, along with a handful of allies, sharply chastised Gingrich for liking earmarks and big spending; Gingrich in return called them “jihadists.”7 Neumann, the only freshman appointed to the Appropriations Committee, insisted on bucking the leaders and promoting his own budget, while voting regularly against the committee leaders. (In 1997, he committed party apostasy by voting “present” for Speaker, meaning he was openly refusing to cast his ballot for Gingrich.) At the urging of Gingrich and other leaders, most left their families in their districts and spent as little time in Washington as possible. Some, like Mark Sanford of South Carolina, eschewed a Washington residence and slept in their offices, as a mark of their determination not to be captured by the evil Capitol culture.

Gingrich wanted to establish the House almost as a parallel government, challenging the president and his policy initiatives—and his very ability to shape the agenda—at every turn. Believing that Clinton was soft and would cave to pressure, enabling the House Republicans to move from winning an election for Congress to taking effective charge of the government and implementing a sweeping policy revolution, he confronted Clinton and challenged established policies at every turn. Most of his efforts centered on issues in the Contract with America, the conservative pledge he and Republican candidates had run on in the 1994 election, that included elements like a balanced budget amendment, a tough crime package, and term limits for members of Congress. The business community, which had benefited from clean air rules, repelled his early attempt to erase existing environmental regulations.

Most of the congressional challenge to Clinton came over budget-related matters, as the House Republicans tried to use the threat of a breach in the debt limit and of shutdowns in major parts of the government to bludgeon the president into accepting their demands to cut spending and cut regulations and taxes. A series of threats and confrontations culminated at the end of the Speaker’s first year in two government shutdowns, which backfired on Gingrich and his party. To his credit, Gingrich saw that his overreach and hubris threatened his majority’s ability to win a second term; he was still popular enough to convince his colleagues to pivot and work with the president and to have sufficient accomplishments to mollify voters, even if it meant burnishing Clinton’s status at the same time.

A new, if brief, period of bipartisan cooperation followed in 1996 on welfare and modest health reform that helped Clinton win reelection and Gingrich to lead his party to a second consecutive term in the majority, albeit with a smaller margin. But the bitterness and rancor he had triggered in his time in the minority blew back against him as he approached his second term as speaker. Democrats brought a slew of ethics charges against Gingrich, including some stunningly similar to the charges that Gingrich had brought against Jim Wright nine years earlier. His speakership hung in the balance, but unlike Wright, he managed to hold on, in a deal that included a reprimand by the House for claiming tax-exempt status for a college course that was used for political purposes, and for repeatedly misleading the House and its ethics investigators, and a $300,000 fine.

Two years later, it was a different matter. His reign as Speaker, which had been both consequential and troubled, ended ignominiously in the heat of the Republican effort to impeach President Clinton. In spite of strong public sentiment against forcing Clinton from office for his misbehavior in the Monica Lewinsky affair, Gingrich orchestrated a last-minute advertising blitz to make the impeachment debate an electoral liability for the Democrats in the 1998 midterm elections. The effort backfired, the Democrats won five seats (reversing the historic pattern of midterm seat losses by the president’s party), and pressure built within his party caucus for Gingrich to resign.

Gingrich left with barely a whimper, but remained a visible figure in both political and policy circles by building an extensive network of advocacy organizations. By the time he ran for president in 2011, he had evolved fully from the pragmatic, relatively nonideological though intensely ambitious new member of Congress who first plotted to take majority control of the Congress, to what now passes for a conventional right-wing populist, abandoning long-held positions on health-care reform and cap-and-trade, for example, to cater to the new Tea Party–driven forces that have co-opted the GOP.

Gingrich deserves a dubious kind of credit for many of the elements that have produced the current state of politics. He crystalized the approach of crafting a cohesive, parliamentary-style minority party and using it as a battering ram to stymie and damage a president of the other party. By moving to paint with a broad brush his own institution as elitist, corrupt, and arrogant, he undermined basic public trust in Congress and government, reducing the institution’s credibility over a long period. His attacks on partisan adversaries in the White House and Congress created a norm in which colleagues with different views became mortal enemies. In nationalizing congressional elections, he helped invent the modern permanent campaign, allowing electoral goals to dominate policy ones; the use of overheated rhetoric and ethics charges as political weapons; and the take-no-prisoner politics of confrontation and obstruction that have become the new normal. Many members of the House freshman class of 1994, and others who were Gingrich allies like Rick Santorum, ultimately moved to the Senate, taking the norms they had inculcated in the House to the previously more restrained Senate and helping to move its culture in a more confrontational and obstructive direction.8

Of course, the dynamic was not entirely one-sided. The tit-for-tat exchanges on ethics cut both ways. If Gingrich had mastered the extensive use of character assaults for political ends, the Democrats took the confrontation over judicial nominations to a new level with their brutal attacks on Robert Bork in 1987. This in turn enraged conservatives nationally and particularly in the Senate, leading to an endless cycle of confrontation over judicial nominees.9 But one has to look back to Gingrich as the singular political figure who set the tone that followed.

If Gingrich and his allies set the table for today’s dysfunction, with more than a dollop of help from his adversaries, they were not operating in a vacuum. The seeds of the partisan divide had been planted much earlier, and its roots are deep and strong.

Partisan polarization is undeniably the central and most problematic feature of contemporary American politics. Political parties today are more internally unified and ideologically distinctive than they have been in over a century. This pattern is most evident in the Congress, state legislatures, and other bastions of elite politics, where the ideological divide is wide and where deep and abiding partisan conflict is the norm. But it also reaches the activist stratum of the parties and into the arena of mass politics, as voters increasingly sort themselves by ideology into either the Democratic or Republican Party and view politicians, public issues, and even facts and objective conditions through distinctly partisan lenses.

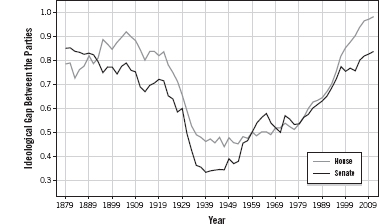

Scholars have amply measured and established the sharp increase in polarization over the last three decades. We can see it in roll call voting patterns in the House and Senate. As Figure 2-110 shows, the period from the end of Reconstruction through the first decade of the twentieth century was also a deeply partisan one, reflecting divisions on issues like farming and whether the United States should rely on the gold or silver standard for its money. Earlier periods in American history also experienced sharp partisan conflict—from battles over federalism in the early decades of the republic to slavery in the 1850s.11 But for most of the past century, the parties were less internally unified and ideologically distinctive, and more coalitions in Congress cut across parties than is the case today. All the evidence on parties in government in recent years points to very high unity within and sharp ideological and policy differences between the two major parties. As National Journal reported in its study of roll call voting in the 111th Congress, for the first time in modern history, in both the House and Senate, the most conservative Democrat is slightly more liberal than the most liberal Republican. This is another way of saying that the degree of overlap between the parties in Congress is zero.12

Figure 2-1 Party Polarization, 1879–2010:

Ideological Gap Between the Parties.

Similar patterns are apparent among party activists of all sorts—delegates to national party conventions, local opinion leaders, issue advocates, donors, and participants in nominating caucuses and primaries. All increasingly share the ideological perspective and issue positions of their party’s elected officials.13

Contrary to the impression left by many stories in the press, members of the public have also been caught up in partisan polarization, although this varies a good deal by their degree of attachment to one of the parties, their level of information about politics and public affairs, and whether they vote. The general public surely remains less interested and engaged in public affairs, less ideological, and more instinctively pragmatic and open to compromise than the political class.14 Hot-button social issues of transcendent importance to activists, such as abortion and same-sex marriage, seldom register high on the list of priorities for the broad public. The style and tone of partisan debate is often unsettling to ordinary citizens. But as a number of scholars have demonstrated,15 critical segments of the general public have been pulled in the same directions as political elites. Voters are more ideologically polarized than nonvoters. More educated, informed, and engaged voters are more polarized than less educated, informed, and engaged voters. Those voters who identify themselves as independents without leaning toward one of the parties (less than 10 percent of the electorate) are mostly bereft of any ideological framework or well-defined issue positions, unlike those who identify or lean toward a party. But active and engaged Democrats and Republicans view the political world through such sharply different lenses—with different perceptions of reality—that their worldviews reinforce the polarization of their elected representatives.

What caused the party polarization? It would be nice if we could boil it down to a single root cause. The pundits’ favorite cause, in spite of impressive evidence to the contrary,16 is the gerrymandering of legislative districts. Redistricting does matter somewhat. It contributes to party polarization by systematically shaping more safe districts for each party, thereby helping to create homogeneous echo chambers, to make party primaries the only real threat to representatives, and to enhance the power of the small number of activist ideologues who dominate in primaries. But that impact is relatively minor and marginal. A recounting of recent history (buttressed by a good deal of scholarly research) reveals that polarization has multiple roots and that those roots are entwined and run deep.17

The story begins with the fissures in the Democratic Party’s New Deal coalition that were evident in the 1960s, with an initial weakening of the party’s stronghold in the South, the rise of the counterculture, and opposition to the war in Vietnam. The 1964 presidential campaign of Barry Goldwater initiated a long-term struggle among Republican activists to develop a more distinctly conservative party agenda. While Goldwater got trounced in the election, he did win (in addition to his home state of Arizona) five Southern states, aided by his outspoken support of states’ rights. The five states included Alabama, Mississippi, and South Carolina for the first Republican victory since Reconstruction, and Georgia for the first time ever.

This was followed by the passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, which, along with the ongoing economic development in the South, began to break the hegemony of conservative whites that had allowed the Democrats to dominate the region for many decades. The Supreme Court’s 1973 abortion decision in Roe v. Wade galvanized a pro-life movement that years later would form the core of the Republican Party’s largest and most reliable constituency, the religious conservatives. California’s tax-limiting Proposition 13 in 1978 and the emergence of Ronald Reagan on the national political scene gave the Republican Party a more distinctive economic platform. As president, Reagan vigorously challenged the Soviet Union, adding national security to the set of issues dividing the parties.

Party realignment in the South—fueled by the developments associated with race, religious fundamentalism, economic development, and patriotism—led to a sharp decline in the number of conservative Democrats serving in Congress and an increase in the number of conservative Republicans. In 1980, conservative Democrats made up at least a third of the party; the numbers regularly declined, until they reached roughly 10 percent of the party in 2011. At the same time, the remaining Southern Democrats consisted largely of liberals (mostly minorities). The shift was accelerated by the redistricting coalitions that developed between Republicans and African Americans eager to increase their numbers in Congress by creating majority-minority districts. For Republicans, this meant “packing” Democrats into safe urban districts, giving the GOP more opportunities to win swing suburban seats, while minorities got more representation in districts that had substantial majorities of African-American voters. Those forces alone accounted for most of the increased ideological polarization between the parties in Congress.

The change in the South was enhanced as well by changing migration patterns, as more senior citizens moved to the Sunbelt from colder climes. The late congressional scholar Nelson Polsby noted that the increase in air conditioning, which meant that people could tolerate the oppressive summers in the South, enhanced this trend.18 As Republican-oriented senior citizens, who came of age before the New Deal, moved South, the regions they left, including New England and the rest of the Northeast, lost a sizable portion of their Republican voting base, endangering the mostly moderate and liberal Republicans who had historically won in those areas.

Parallel changes occurred on the West Coast, which had been a bastion of moderate Republicanism via lawmakers like Mark Hatfield of Oregon and Tom Kuchel of California. But the movement of Asians and Mexican Americans into states like California, Washington, and Oregon, along with others who were drawn to the environmentally conscious and socially moderate atmosphere on the West Coast, turned those states from the 1960s through the 1980s into reliably Democratic strongholds, even as they contributed to the demise of moderate Republicans in Congress.

As these developments played out over time, Democrats in Congress became more homogeneous and drifted left, Republicans became more homogeneous and veered sharply right, and party platforms became more distinctive. The realigning process initiated in the South and then extended to the rest of the country was further fueled by the increasingly distinctive positions that the national parties and their presidential candidates took on a number of salient social and economic issues. Those recruited to Congress (or motivated to run on their own) were more ideologically in tune with their fellow partisans, congressional leaders were given the authority to aggressively promote their party’s agenda and message, interest groups increasingly aligned themselves with one party or the other, network news lost audience share and was challenged by more partisan cable news and talk radio, and voters across the country gradually adjusted their party attachments to fit their ideological views.19

At the same time, voters were making residential decisions that reinforced the ideological sorting already under way.20 Citizens were drawn to neighborhoods, counties, states, and regions where others shared their values and interests. This ideological sorting, geographic mobility, and more consistent party-line voting produced many areas that were dominated by a single party at the municipal, county, and state levels, and in state legislative and congressional districts. Contrary to then Illinois state senator Barack Obama’s demurral at the 2004 National Democratic Convention in Boston, the portrait of a red and blue nation had some considerable basis in reality. In turn, the increasing partisan homogeneity of political jurisdictions, exacerbated in legislative districts by redistricting practices, diminished electoral competition and reinforced the polarizing dynamic between political elites and voters.

There is another element in this dynamic that has contributed mightily to the amplification of dysfunction—the fact that 1994 brought with it not just the first Republican House in forty years, but also a new era of toss-up elections with party control at stake. Polarized parties raised the stakes of each election by enlarging the consequences of a change in party control. If there had been a shift in party control when we first came to Washington in 1969, it would have meant a move from one figurative forty-yard line to the other. Now it means a move from one goalpost to the opposite twenty-five yard line, or vice versa.

The Republican Party, especially after taking the majority in 1995, honed its political machine to boost both electoral and legislative prospects. Both parties, seeing higher stakes, changed their fund-raising strategies to put a high priority on redistributing resources from the many safe districts to the few remaining competitive ones, effectively involving all members in the larger campaign to retain or achieve majority status. Regular order in the legislative process—the set of rules, practices, and norms designed to ensure a reasonable level of deliberation and fair play in committee, on the floor, and in conference—was often sacrificed for political expediency.21 That meant, among other things, constraining debates and amendments, and the virtual demise of the conference committees traditionally used to work out the differences between the House and Senate to allow leaders to shape bills behind closed doors. The most egregious case remains the outrageous three-hour vote in 2003 in the wee hours of the morning, violating numerous House rules and norms, to pass the Medicare prescription drug bill.

The election in 2000 of the first unified Republican government since 1952—but with the president elected by a minority of popular votes in the most controversial election in more than a century, a fifty-fifty Senate, a slender majority in the House, and efforts to jam through serious policy on party lines—further hardened party divisions in Congress. The return of a unified Democratic government in 2008 with the election of President Barack Obama significantly extended and intensified the war between the parties. The Republicans’ smashing victory in the 2010 midterm elections, after two elections in 2006 and 2008 that were “waves” in favor of Democrats, produced yet another jump in the level of partisan polarization in the House, setting the stage for the debt ceiling fiasco that has come to exemplify the current dysfunctional politics.

There is no doubt that greater ideological agreement among members in both parties was a prerequisite to an increase in partisanship in Congress. Congressional scholars call it “conditional party government.”22 Like-minded party members representing more homogeneous constituencies are willing to delegate authority to their leaders to advance their collective electoral interests, putting a premium on strategic partisan team play. Building and maintaining each party’s reputation dictate against splitting the difference in policy terms. It’s better to have an issue than a bill, to shape the party’s brand name and highlight party differences.23 The extent of change toward tribalism is clear when party line voting spills over to issues with no discernable ideological content and where liberal and conservative positions are impossible to identify.24

It is traditional that those in the American media intent on showing their lack of bias frequently report to their viewers and readers that both sides are equally guilty of partisan misbehavior. Journalistic traditions notwithstanding, reality is very different. The center of gravity within the Republican Party has shifted sharply to the right. Its legendary moderate legislators in the House and Senate are virtually extinct. To be sure, a sizable number of the Republicans in Congress are center-right or right-center, rather than right-right. But the insurgent right wing regularly drowns them out. The post-McGovern Democratic Party, while losing the bulk of its conservative Dixiecrat contingent, has retained a more diverse constituency base, and since the Clinton presidency, has hewed to the center-left, with an emphasis on the center, on issues ranging from welfare reform to health policy.

Anyone who has reviewed the voluminous literature on the intellectual and organizational developments within the conservative movement and Republican Party since the 1970s will find that an unremarkable assertion.25 The conservative critique of the Great Society social welfare programs and of the regulatory state, the mobilization of the Christian right, and the development of supply-side economics set the policy plate of the modern Republican Party. Over the course of the last three decades, the GOP has become the reflexive champion of lower taxes, reductions in the size and scope of the federal government, deregulation, and the public promotion of a religious and cultural conservatism. The striking changes in the nature of the Republican Party over the past fifty years are especially well documented in the book by political historian Geoffrey Kabaservice, Rule and Ruin: The Downfall of Moderation and the Destruction of the Republican Party, From Eisenhower to the Tea Party. He notes, “movement conservatism finally succeeded in silencing, co-opting, repelling, or expelling nearly every competing strain of Republicanism from the party, to the extent that the terms ‘liberal Republican’ or ‘moderate Republican’ have practically become oxymorons.”26

Republican presidents Eisenhower and Nixon and congressional leaders such as Senators Everett Dirksen, Hugh Scott, Howard Baker, and Bob Dole, and Representatives Gerald Ford, John Rhodes, and Bob Michel, pragmatic institutional figures who found ways to work within the system and focused on solving problems, are unimaginable in the present context. President Reagan ushered in the new Republican Party but governed pragmatically. The steps he took in office, as well as those the two Bush presidents took, were so far outside the policy and procedural bounds of the contemporary GOP that none of them could likely win a Republican presidential nomination today without disavowing their own actions. Reagan was a serial violator of what we could call “Axiom One” for today’s GOP, the no-tax-increase pledge: he followed his tax cuts of 1981 with tax increases in nearly every subsequent year of his presidency.27 George H. W. Bush agreed to a 1990 deficit-reduction package that included tax increases and budget process reforms, turning back significant congressional Republican opposition (led by Newt Gingrich) along the way. And in more recent years, conservatives turned sharply against George W. Bush’s advocacy of broad immigration reform (a violation of “Axiom Two”), expansion of government in health care and education (Oops! There goes “Axiom Three”), and steps to deal with the financial meltdown. That legacy, and Barack Obama’s election and extraordinary measures to limit the damage from the financial crisis and deep recession, prompted the formation of a right-wing populist Tea Party movement, which the Republican establishment subsequently embraced.

Chuck Hagel, the former Republican Senator from Nebraska, echoed just these points in an August 2011 interview with the Financial Times. Hagel called his party “irresponsible” and said he was “disgusted” by the antics of the Republicans over the debt ceiling:

The irresponsible actions of my party, the Republican Party over this were astounding. I’d never seen anything like this in my lifetime. . . . I was very disappointed. I was very disgusted in how this played out in Washington, this debt ceiling debate. It was an astounding lack of responsible leadership by many in the Republican Party, and I say that as a Republican. . . . I think the Republican Party is captive to political movements that are very ideological, that are very narrow. I’ve never seen so much intolerance as I see today in American politics.28

A veteran Republican congressional staffer, Mike Lofgren, wrote a long and anguished essay/diatribe in 2011 about why he ended his career on the Hill after nearly thirty years. His essay was filled with observations and broadsides like the following:

It should have been evident to clear-eyed observers that the Republican Party is becoming less and less like a traditional political party in a representative democracy and becoming more like an apocalyptic cult, or one of the intensely ideological authoritarian parties of 20th century Europe.

He added,

The only thing that can keep the Senate functioning is collegiality and good faith. During periods of political consensus, for instance, the World War II and early post-war eras, the Senate was a “high functioning” institution: filibusters were rare and the body was legislatively productive. Now, one can no more picture the current Senate producing the original Medicare Act than the old Supreme Soviet having legislated the Bill of Rights.

Far from being a rarity, virtually every bill, every nominee for Senate confirmation and every routine procedural motion is now subject to a Republican filibuster. Under the circumstances, it is no wonder that Washington is gridlocked: legislating has now become war minus the shooting, something one could have observed 80 years ago in the Reichstag of the Weimar Republic. As Hannah Arendt observed, a disciplined minority of totalitarians can use the instruments of democratic government to undermine democracy itself.

And then this observation:

A couple of years ago, a Republican committee staff director told me candidly (and proudly) what the method was to all this obstruction and disruption. Should Republicans succeed in obstructing the Senate from doing its job, it would further lower Congress’s generic favorability rating among the American people. By sabotaging the reputation of an institution of government, the party that is programmatically against government would come out the relative winner.29

Lofgren’s frustration may make him more prone to hyperbole than other old-school Republicans—but his observations hit home with many of them, as they do with us.

The GOP’s nearly unanimous pledge, in writing, not to increase taxes under any circumstance is perhaps the best indicator and most consequential component of its ideological thrust. Grover Norquist, president of Americans for Tax Reform and the man who fashioned the “Taxpayer Protection Pledge” to which Republicans pay fealty, has become a legendary power broker in the party. At the same time, its rank-and-file voters endorse the broader strategy the party elites have adopted, eschewing compromise to solve problems and insisting on sticking to principle even if it leads to gridlock.30

The Democrats under the presidencies of Clinton and Obama, by contrast, have become the more status-quo oriented, centrist protectors of government, willing to revamp programs and trim retirement and health benefits in order to maintain the government’s central commitments in the face of fiscal pressures and global economic challenges.31 And rank-and-file Democrats (along with self-identified Independents) favor compromise to solve problems over deadlock.32

The contrast plays out in a number of striking ways. One simple indicator is this: More than 70 percent of Republicans in the electorate identify themselves as conservative or very conservative, while only 40 percent of rank-and-file Democrats call themselves liberal or very liberal.33 This difference at the level of mass politics is reflected in the ideological composition of the two parties in government. George W. Bush pushed through his signature tax cuts and Iraq war authorization with substantial Democratic support, while unwavering Republican opposition nearly torpedoed Barack Obama’s health-care and financial reform legislation. When Democrats are in the majority, their greater ideological diversity combined with the unified opposition of Republicans induces the majority party to negotiate within its ranks, producing policies on health reform and climate change that not long ago would have attracted the support of at least a dozen Senate Republicans and thirty to forty House Republicans. Now? Zero in either chamber.

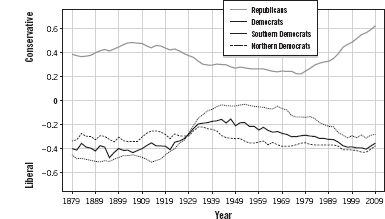

The phenomenon is even clearer when we look at roll call voting averages for parties on the same liberal-conservative dimension over time. Since the late 1970s, Republicans have moved much more sharply in a conservative direction than did Democrats in a liberal direction. And the change that occurred among Democrats was mostly within their Southern contingent—the demise of Dixiecrat conservatives and the election of minorities. Democratic representatives outside the South barely moved at all. (See Figure 2-2 for voting averages.34) The 2010 election dramatically increased the conservative tilt of the House Republicans. Nearly 80 percent of the freshmen Republicans in the 112th Congress would have been in the right wing of the party in the 111th Congress.35

Figure 2-2 Liberal-Conservative Voting Averages in the

House of Representatives 1879–2010.

Another indicator of the rightward shift of Republicans in Congress is the size of the House GOP’s right-wing caucus, the Republican Study Committee, or RSC. Paul Weyrich and other conservative activists created the committee in 1973 as an informal group to pull the center-right party much further to the right; it had only 10 to 20 percent of Republican representatives as members as recently as the 1980s, a small fringe group. In the 112th Congress, the RSC had 166 members, or nearly seven-tenths of the caucus.

Relative ideological shifts between the two parties account for much, but not all of the asymmetric polarization. Part of their divergence stems from factors beyond ideology. As we discussed at the beginning of this chapter, the most important of these are side effects of the long and ultimately successful guerilla war that Newt Gingrich fashioned and led to end the hegemonic Democratic control of the House and national policy making. Other important factors are the rise of the new media and the culture of which it became an essential part, as well as the changing role of money and politics.

As population shifts occurred and helped to trigger partisan and ideological movements, communications in the U.S. and the world were revolutionized, with dramatic implications for political discourse.36 The media world in which we grew up in the 1950s was dominated by three television networks, which captured more than 70 percent of Americans as a regular viewing audience. A healthy majority relied on their news divisions, and especially the nightly news shows, as their primary source of information. Without remote controls, most Americans were passive consumers of that news. Second in line were newspapers. Most metropolitan areas had at least two and often more. While the editorial pages of the newspapers often had distinct party leanings, the news pages usually bent over backward to report news objectively, avoiding rumor or hearsay and relying on facts (with the exception of celebrity gossip columns in the tabloids).

Contrast that with the current situation. With the remarkable telecommunications revolution, there has been a veritable explosion of media. Adam Thierer of the Progress and Freedom Foundation pointed out in 2010 that there were almost 600 cable television channels, over 2,200 broadcast television stations, more than 13,000 over-the-air radio stations, over 20,000 magazines, and over 276,000 books published annually. As of December 2010, there were 255 million websites, and over 110 million domain names ending in .com, .net, and .org, and there were over 266 million Internet users in North America alone.37

Thierer also observed in early 2010:

There are an estimated 26 million blogs on the Inter net. YouTube reports that 20 hours of video are uploaded to the site every minute, and 1 billion videos are served up daily by YouTube, or 12.2 billion videos viewed per month. For video hosting site Hulu, as of Nov. 2009, 924 million videos were viewed per month in the U.S. Developers have created over 140,000 Apps for the Apple iPhone and iPod and iPad and made them available in the Apple App Store. Customers in 77 countries can choose apps in 20 categories, and users have downloaded over three billion apps since its [the iPhone’s] inception in July 2008.38

The plethora of channels, websites, and other information options has fragmented audiences and radically changed media business models. The fragmentation also applies to attention spans. In 1950, the average weekly usage of a TV set was just over thirty hours, and the time per channel was twelve hours. By 2005, weekly TV set usage was up to nearly sixty hours, but time per channel was down to three hours. In the old days, the network news shows viewed themselves (and viewers deemed them so) as a public trust, were not required to be separate cost centers for their networks, and provided, along with newspapers and newsreels, a common set of facts and core of information that were widely shared.

Now, network news divisions have cut back dramatically on their news personnel and range of coverage as their share of viewers has declined to a tiny fraction of past numbers, and they rank far down as people’s primary sources of information. The nightly news shows do provide a kind of headline service for viewers, but with more soft news about entertainment, lifestyle, and sports and with fewer in-depth pieces or extended interviews with sources. Local broadcast stations have found significant success with local news, but not of the political variety. Coverage of local elections or local politicians has declined dramatically.39

Cable news networks now compete with broadcast networks for news viewership. While their number of viewers remain less than the broadcast news channels, their business models enable them to be potentially more profitable. In 2010, Fox News returned a net profit of $700 million, more than the profits of the three network news divisions combined,40 and one-fifth of Newscorp’s total profits, despite the fact that Fox nightly news shows get around two million viewers, compared to the twenty million combined for the three network nightly newscasts. At the same time, broadcast news divisions are struggling and go through regular layoffs and cutbacks in domestic and international bureaus and of news personnel.

The Fox business model is based on securing and maintaining a loyal audience of conservatives eager to hear the same message presented in different ways by different hosts over and over again. MSNBC has adopted the Fox model on the left, in a milder form (especially in the daytime). CNN has tried multiple business models, but has settled on having regular showdowns pitting either a bedrock liberal against a bedrock conservative or a reliable spinner for Democrats against a Republican counterpart. For viewers, there is reinforcement that the only dialogue in the country is between polarized left and right, and that the alternative is cynical public relations with no convictions at all. The new business models and audiences are challenging the old notion that Americans can share a common set of facts and then debate options.

Pew Research Center studies have found that the audiences for Fox, CNN, and MSNBC are sharply different when it comes to partisan identity and ideology.41 Another survey also noted differences between Fox viewers and the general public on attitudes and facts: “When compared against the general population, Fox News viewers are significantly less likely to believe that [President] Obama was born in the US, and that one of the most important problems facing the US is leadership. . . . Fox viewers are significantly less optimistic about the country’s direction.”42 There is little doubt that Fox News is at least partly responsible for the asymmetric polarization that is now such a prominent feature of U.S. politics.

Newspapers, of course, are struggling even more than television networks. For years, polls showing declining readership among young generations forebode declining circulation. Because of waning ad revenues, especially from the bread-and-butter classified ads now supplanted by Craigslist and other online services like it, many newspapers have folded or merged with others for survival, creating more one-newspaper towns. Even more than networks, newspapers have reduced reporting corps and folded bureaus. One result has been the sharply reduced oversight of political figures and policy makers, and thus fewer checks and balances on their behavior.

America has gone back to the future with the new and prominent role of partisan media, just as in much of the nineteenth century but with far more reach, resonance, and scope than at any earlier period. The Fox News model—combative, partisan, sharp-edged—is the most successful business model by far in television news.

With the increased competition for eyeballs and readers, all media have become more focused on sensationalism and extremism, on infotainment over information, and, in the process, the culture has coarsened. No lie is too extreme to be published, aired, and repeated, with little or no repercussion for its perpetrator. The audiences that hear them repeatedly believe the lies, Obama’s birthplace a prime example. A late-September 2011 Winthrop University survey of South Carolina Republicans found that 36 percent of those polled believed that the president was probably or definitely born outside the United States, a drop of only 5 percent from 41 percent in April, before the official release of his long-form birth certificate.43 Barraged with media reports, including blogs and viral e-mails, and already convinced through years of messaging, these voters are inured to factual information. A world in which substantial numbers of Americans believe that the duly elected president of the United States is not legitimate is a world in which political compromise becomes substantially more difficult.

In a fragmented television and radio world of intense competition for eyeballs and eardrums sensationalism trumps sensible centrism. The lawmakers who get attention and airtime are the extreme and outrageous ones. For lawmakers, then, the new role models are people like Joe Wilson, Michele Bachmann, and Alan Grayson, the first two still in Congress. Outrageous comments result in celebrity status, huge fund-raising advantages, and more media exposure. Mild behavior or political centrism gets no such reward.

In addition to lawmakers, the bombastic and blustering figures in the political culture—the Ann Coulters, Michael Moores, and Erick Ericksons—are rewarded with huge book sales and cable jobs. Coulter’s book titles range from Godless to Slander to Guilty to Demonic to Treason, all about liberals in America. The language is not conducive to debate and deliberation, but is now guaranteed to bring spots on the best-seller lists and huge lecture fees. Periodically, Coulter will say something so offensive and outrageous, or so wrong, that cable networks pledge to stop putting her on the air. That moratorium lasts, on average, for a few months, until the ratings drive in the new age overcomes the shame of showcasing a grenade-throwing extremist.

Beyond the bombast driven by the new media models, there are other sources of inflammatory rhetoric and misinformation, from tweets to blogs to viral e-mails. A good and persistent example of the latter is an e-mail that keeps circulating and being forwarded in bulk despite major efforts to debunk it. It reads in part:

No one has been able to explain to me why young men and women serve in the U.S. Military for 20 years, risking their lives protecting freedom, and only get 50% of their pay. While politicians hold their political positions in the safe confines of the capital, protected by these same men and women, and receive full pay retirement after serving one term.

Monday on Fox news they learned that the staffers of Congress family members are exempt from having to pay back student loans. . . .

For too long we have been too complacent about the workings of Congress. Many citizens had no idea that members of Congress could retire with the same pay after only one term, that they specifically exempted themselves from many of the laws they have passed (such as being exempt from any fear of prosecution for sexual harassment) while ordinary citizens must live under those laws. The latest is to exempt themselves from the Healthcare Reform . . . in all of its forms.44

In reality, all the “facts” in the e-mail are wrong. Here’s a Congressional Research Service report on pensions:

Congressional pensions, like those of other federal employees, are financed through a combination of employee and employer contributions. . . . Members of Congress are eligible for a pension at age 62 if they have completed at least five years of service. Members are eligible for a pension at age 50 if they have completed 20 years of service, or at any age after completing 25 years of service. The amount of the pension depends on years of service and the average of the highest three years of salary. By law, the starting amount of a Member’s retirement annuity may not exceed 80% of his or her final salary.

As of October 1, 2006, 413 retired Members of Congress were receiving federal pensions based fully or in part on their congressional service. Of this number, 290 had retired under [the Civil Service Retirement System] and were receiving an average annual pension of $60,972. A total of 123 Members had retired with service under both CSRS and [the Federal Employees Retirement System] or with service under FERS only. Their average annual pension was $35,952 in 2006.45

On the Fox News assertion about student loans, this from factcheck.org (responding to dozens of inquiries):

Are members of Congress exempt from repaying student loans?

Are members’ families exempt from having to pay back student loans?

Are children of members of Congress exempted from repaying their student loans?

Do congressional staffers have to pay back their student loans?

The answers are: no, no, no and yes—although some full-time congressional staffers participate in a student loan repayment program that helps pay back a portion of student loans. No more than $60,000 in the House and $40,000 in the Senate can be forgiven and only if the employee stays on the job for several years.46

The assertion that members of Congress are exempt from the provisions of the Affordable Care Act is also false. Members of Congress are subject under the health-care reform law to the same mandate as others to purchase insurance, and their plans must have the same minimum standards of benefits that other insurance plans will have to meet. Members of Congress currently have no gold-plated free plan, but the same insurance options that most other federal employees have, and they do not get it free. They have a generous subsidy for their premiums, but no more generous (and, compared to many businesses or professions, less generous) than standard employer-provided subsidies throughout the country.47

This e-mail is a new political version of an urban legend, but with serious consequences. Former Senator Robert Bennett (R-Utah) has reported that a Tea Party activist who challenged Bennett’s renomination to the Senate (he was blocked from even running for reelection as a Republican in 2010) said he was motivated to run by that e-mail. The exaggerated views of politicians reinforced here enhance the anti-politician populism that fueled the Tea Party movement. In the new age and the new culture, the negative and false charges are made rapidly and are hard to counter or erase. They also make rational discourse in campaigns and in Congress more difficult and vastly more expensive.

Viral e-mails and word-of-mouth campaigns are expanding sharply, mostly aimed at false facts about political adversaries. As the Washington Post’s Paul Farhi notes in an article titled, “The e-mail rumor mill is run by conservatives,” they are overwhelmingly coming from the right and are aimed at President Obama and other liberals—and they are powerful:

Grass-roots whisper campaigns such as these predate the invention of the “send” button, of course. No one needed a Facebook page or an e-mail account to spread the word about Thomas Jefferson’s secret love child or Grover Cleveland’s out-of-wedlock offspring (both won elections despite the stories, which in Jefferson’s case were very likely true).

But it has become a truism that in their modern, Internet-driven form, these persistent narratives spread far faster and run deeper than ever. And they share an unexpected trait: Most of the time, Democrats (or liberals) are the ones under attack. Yes, George W. Bush had some whoppers told about him—such as his alleged scoffing that the French “don’t have a word for ‘entrepreneur’”—but when it comes to generating and sustaining specious and shocking stories, there’s no contest. The majority of the junk comes from the right, aimed at the left.

We’re not talking here about verifiably inaccurate statements from the mouths of politicians and party leaders. There’s plenty of that from all sides. And almost all of those statements are out in the open, where they get called out relatively quickly by the opposition or the mainstream media.

Instead, it’s the sub rosa campaigns of vilification, the can-you-believe-this beauts that land periodically in your inbox from a trusted friend or relative amid the noise of every political season.

This sort of buzz occurs out of earshot of the news media. It gains rapid and broad circulation by being passed from hand to hand, from friend to relative to co-worker. Its power and credibility come from its source. . . .

Of the 79 chain e-mails about national politics deemed false by PolitiFact since 2007, only four were aimed at Republicans. Almost all of the rest concern Obama or other Democrats. The claims range from daffy (the White House renaming Christmas trees as “holiday trees”) to serious (the health-care law granting all illegal immigrants free care).48

The impact of all this is to reinforce tribal divisions, while enhancing a climate where facts are no longer driving debate and deliberation, nor are they shared by the larger public.

Author Robert Kaiser struck a chord when he titled his recent book So Damn Much Money.49 American elections are awash in money, politicians devote an inordinate amount of their time dialing for dollars, and campaign fund-raising is now considered a normal part of the lobbying process.

Kaiser’s book was mostly about lobbying. In a city where much of the business is about divvying up over $3 trillion in federal spending and carving out tax breaks from over $2 trillion in revenues, the money spent on influencing those decisions has mushroomed, and the money that lobbyists and their associates make has become almost mind-boggling. The corruption that Kaiser describes—direct and indirect, from literal or near bribes and the trading of favors to the insidious corruption of the revolving door, where lawmakers and other public officials leave office and become highly paid lobbyists asking for favors from their former colleagues and using their expertise to influence the passage and implementation of laws and regulations—has moved from a chronic problem to an acute one. It was dampened a bit after the uproar of the Jack Abramoff–Tom DeLay era that ended with Abramoff’s conviction and DeLay’s departure from Congress in 2006, or perhaps more accurately, in 2010 with the conviction of Kevin Ring, one of Abramoff’s associates, over a series of bribes and lavish perks provided to lawmakers and staff in return for legislative benefits. But the money in Washington and the problems of the revolving door have barely abated and, with the new era of campaign finance since the Supreme Court’s Citizens United decision, have in many ways become shockingly worse.

In 2011, Jack Abramoff himself came out of exile as a repentant sinner and talked openly about the corrupt system in Washington, vividly describing the depth of rot. On November 6, 2011, Abramoff appeared on 60 Minutes and described how he had corrupted congressional staffers:

When we would become friendly with an office and they were important to us, and the chief of staff was a competent person, I would say or my staff would say to him or her at some point, “You know, when you’re done working on the Hill, we’d very much like you to consider coming to work for us.” Now the moment I said that to them or any of our staff said that to ’em, that was it. We owned them. And what does that mean? Every request from our office, every request of our clients, everything that we want, they’re gonna do. And not only that, they’re gonna think of things we can’t think of to do.50

While Abramoff was caught and served prison time, the fundamentals of the system he described have not changed. If other lobbyists do not operate with his flamboyance, the system awash in money still operates as it did in 2006. One vivid example is “Newt, Inc.,” the name observers of Newt Gingrich coined after he left Congress. The industrious Gingrich created a web of for-profit and not-for-profit groups that garnered nearly $150 million in fees from a wide array of businesses and trade associations. Newt’s influence-for-hire operation included the now well-publicized $1.6 million to $1.8 million from Freddie Mac to legitimize its efforts with House Republicans, and over $30 million from health-care-related organizations. Gingrich said he did no lobbying, but of course, it’s hard to figure out what his clients were buying other than access to policy makers.

To be sure, money has long played a problematic role in American democracy. Reconciling the tension between economic inequality and political equality, while preserving the constitutional guarantee of free speech, is no easy task. A healthy democracy with open and competitive elections requires ample resources for candidates to be heard and voters to garner the information they need to make considered decisions. This country has regulated campaign finance for over a century, though often with weak and porous statutes and grossly inadequate means of enforcement.51 A major increase in recent decades in the demand for and supply of money in politics directly exacerbates dysfunctional politics by threatening the independence and integrity of policy makers and by reinforcing partisan polarization.

The first flows from the inadequate measures to limit the source and size of contributions to candidates and parties. Prohibitions on corporate contributions in federal elections were enacted early in the twentieth century; these were extended to direct spending as well as contributions from corporations and unions in the 1940s. Violations of these laws by the Committee to Reelect the President in the 1972 election led to the passage of a more ambitious regulatory regime that added contribution limits, public funding of presidential campaigns, and more effective public disclosure.

By the 1990s, parties found ways of raising so-called soft money—unlimited contributions from corporations, unions, and individuals ostensibly used for purposes other than influencing federal elections. The availability of these unrestricted sources of campaign funds created increased opportunities for inappropriate pressure and conflicts of interest if not outright extortion or bribery between public officials and private interests.

Stories of politicians using elaborate inducements to raise huge sums of soft money from big donors (including sleepovers in the Lincoln Bedroom and—literally—menus of intimate access to key committee chairs in Congress or top party leaders based on levels of soft money contributions) led to a drive for major reform. It was intensified by the growing impact of “independent” outside and party ads, financed by soft money from individuals, corporations, and unions, using a loophole in the regulations that allowed unlimited funds for so-called “issue ads.” The ads did not say explicitly “elect” or “defeat” a candidate, but in every other respect were aimed at voters in a district or state to influence the election outcomes.

The Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act (known widely as the McCain-Feingold Act), passed in 2002, was designed to prohibit party soft money and to bring electioneering communications (those campaign ads parading as issue ads) under the contribution and disclosure restrictions of the law. The Supreme Court upheld it in 2003, in McConnell v. Federal Election Commission.

That law worked as intended, until it was overwhelmed by a series of Supreme Court decisions, which, in combination with a lax Federal Election Commission and increasingly brazen entrepreneurs pushing the boundaries of the law beyond recognition, have created the political equivalent of a new Wild West. Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission, decided by a 5–4 majority in 2010, was the centerpiece of the Court’s recent deregulatory juggernaut to overturn decades of law and precedent. In a breathtaking breach of judicial norms dealing with cases and controversies and legal precedents, the Court ruled that corporations and unions were free to make unlimited independent expenditures in elections for public office. Step back for a moment and look at the trajectory of this case.52 The plaintiff, Citizens United (a conservative group), narrowly challenged a provision of the 2002 Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act to enable in this situation unlimited corporate advertising funding for a “documentary” film called Hillary: The Movie. The film was unabashedly designed to derail Hillary Rodham Clinton’s campaign for president. Citizens United wanted only an “as applied” exception for their documentary, which they believed did not meet the standard of “electioneering communications” in the law. They explicitly did not raise the larger question of overturning the ban on corporate spending in federal campaigns.

The Justices heard the case on that basis, but Chief Justice John Roberts, with support from his allies on the Court, decided unilaterally to raise the broader issue of whether a prohibition on corporations’ independent expenditures was constitutional, and he demanded a rehearing. That 5–4 ruling overturned decades of established doctrine, throwing the world of campaign finance into turmoil and demonstrating a troubling new approach to governance by the Supreme Court. The willingness to do something dramatic and highly controversial on a 5–4 vote, underscoring the pattern set in 2000 by the 5–4 highly charged decision that decided the outcome of the presidential election, Bush v. Gore, was accompanied by what we believe was a reckless approach to jurisprudence.

The sweep and scope of the decision was especially disturbing, given what Chief Justice nominee Roberts had vowed at his confirmation hearings in front of the Senate Judiciary Committee in September 2005. In his opening statement, he said:

Judges and justices are servants of the law, not the other way around. They make sure everybody plays by the rules. But it is a limited role. Nobody ever went to a ball game to see the umpire. Judges have to have the humility to recognize that they operate within a system of precedents, shaped by other judges equally striving to live up to the judicial oath. . . . I will remember that it is my job to call balls and strikes and not to pitch or bat.

I do think that it is a jolt to the legal system when you overrule a precedent. . . . It is not enough that you may think the prior decision was wrongly decided. . . . The role of the judge is limited; the judge is to decide the cases before them; they’re not to legislate; they’re not to execute the laws.

Now add the comments Roberts made a year later at the Georgetown University Law Center commencement: “The broader the agreement among the justices, the more likely it is that the decision is on the narrowest possible ground.” He added: “If it is not necessary to decide more to dispose of a case, in my view it is necessary not to decide more.”53

Judges and Congresses in the past had carefully considered the cases overturned and the laws struck down in Citizens United, including in the McConnell decision barely six years earlier. Only one thing had changed—the political and ideological complexion of the Supreme Court brought on in particular by the retirement of Sandra Day O’Connor. Had O’Connor not retired, Citizens United either would not have been broadened or would have been decided 5–4 the other way.

Justice Anthony Kennedy, who drew on reasoning that struck pragmatic observers of money and politics as bizarre, authored the Citizens United decision. He equated money with speech and equated corporations, which have the one goal of making money, with individual citizens, who have many goals and motives in their lives, including making a better society, protecting their children and grandchildren and future generations, and so on. And, as legal scholar Richard Hasen recently noted, Kennedy added gratuitously in the decision his flat statement: “We now conclude that independent expenditures, including those made by corporations, do not give rise to corruption or the appearance of corruption.”54 That statement, belied by the everyday experience of politicians and lobbyists throughout Washington, has opened the floodgates to even more money in politics, and more corruption.

It has also resulted in a substantial infection of judicial elections—something Kennedy, in an earlier opinion (Caperton v. A.T. Massey Coal) had decried, saying (ironically, given his reasoning in Citizens United) that independent expenditures could corrupt judges and courts. A new report by the Brennan Center at New York University looking at judicial elections in 2009–2010 noted: “Nearly 40% of all funds spent on state high court races came from just 10 groups, including national special interest groups and political parties; nearly 1/3 of all funds spent on state high court elections came from non-candidate groups ($11.5 million out of $38 million in 2009-10); and, though outside groups paid for only 40% of total ads, they were responsible for 3 in 4 attack ads.”55

Sure enough, in the wake of Citizens United, political operatives stepped in with creative ways to push the envelope and use huge sums of money both to influence campaigns and to shape legislative outcomes, and to brazenly evade the disclosure requirements for donors that were upheld by the Supreme Court. In one particularly egregious example, former Bush adviser Karl Rove and former Republican National Committee chair Ed Gillespie created two political organizations called American Crossroads. The first, under Section 527 of the Internal Revenue Code, was required to disclose its donors. But the ever-creative Rove also launched a second group, American Crossroads GPS, this one a 501(c)4 under the tax code designed for nonprofit social welfare advocacy organizations. The important thing about these groups is that they don’t have to disclose donors. The second group raised $5.1 million in June 2010 alone, with a goal of reaching $50 million for that election, and according to media accounts, succeeded in its fund-raising because it tapped into sources that did not want to be identified. The “concept paper” describing for potential donors the reasons to support American Crossroads GPS said the group will conduct “in-depth research on congressional expense account abuses,” to blame Democrats for “failed border controls” and to frame the BP oil spill as “Obama’s Katrina.”56

It is impossible to imagine that American Crossroads GPS has any purpose other than electing Republican candidates while keeping the fat-cat donor names hidden from public view. As Politico reporter Ken Vogel noted, Rove created the spinoff group so donors wouldn’t have to be publicly associated with him.57

Rove is not the only political operative seizing on this loophole in IRS regulations to do aggressive partisan campaigning. In February 2010, former Senator Norm Coleman formed a 501(c)4 “action tank” called the American Action Network, which spent a large sum of money in 2010 on attack ads hitting Governor Charlie Crist, who ran as an Independent in the Florida Senate race, and Senator Patty Murray (D-Wash.) in her campaign. Its sister 501(c)3, called American Action Forum, is its “think tank.” Not surprisingly, unions and other liberal and Democratic groups have followed suit, creating a money arms race to attract anonymous large donors.