3

3

3

3

If the debt ceiling mess were the only example of a political system gone wild, it would be easy to say either that it was an anomaly or that the inherent messiness of a disputatious political process—one built around, as the late constitutional scholar Edward Corwin put it, “an invitation to struggle” among and across the branches—makes such showdowns inevitable.1 But the current situation is different. If the politics of partisan confrontation, parliamentary-style maneuvering, and hostage taking has been building since the late 1970s, it has become far more the norm than the exception since Barack Obama’s election. In 2009–2010, when the Democrats controlled the House and Senate as well as the White House, it was all about drawing sharp partisan lines in the dust, with no Republican votes available for any major legislative initiative, save the three Senate Republicans who voted early on for the economic stimulus in return for major concessions to each of them. Since then, the focus has been on Republican unwillingness to cooperate or work with the president except under duress or in an area, like that of free trade agreements with Colombia, Panama, and South Korea, that had long been GOP goals.

In the case of the third prong of the Eric Cantor strategy we outlined in Chapter 1—the continuing resolution standoff for fiscal 2012—Cantor demanded for the first time offsets from other social programs to pay for emergency disaster-relief spending after Hurricane Irene and other natural disasters. At a time when people across the Northeast were confronting mortal threats and devastating personal losses, Cantor and his allies piled on additional anxiety over whether the government was going to help them out or divert their disaster aid to other regions. At the same time, Republicans upped the hostage ante, since paying directly and immediately for disaster relief would mean cutting critical programs like food safety and health research, which had already been hit with budget cutbacks in the fiscal 2011 budget.

Even more troubling was a spat over the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) in the summer of 2011. John Mica, the Republican chairman of the House Transportation and Infrastructure Committee, issued a set of nonnegotiable demands to senators during negotiations over a long-stalled reauthorization of the FAA.2 For many months, lawmakers had regularly extended FAA authority temporarily while they negotiated their differences. Mica, though, insisted that he would no longer keep the agency operating in the absence of an agreement. He would kill any reauthorization unless Democrats in the Senate agreed to reverse a ruling permitting FAA employees to bargain in the same way as other federal employee unions and shut off subsidies to small airports, the latter having especially dire consequences for the key negotiating senators, Jay Rockefeller of West Virginia and Max Baucus of Montana.

There was a case to be made that the subsidies to small and sparsely used airports were an unnecessary use of taxpayer dollars. But Mica’s efforts were not aimed at all such airports, only those in his rival counterparts’ states. At the same time, Mica spurned efforts to compromise on airport subsidies, since they did not include the union bargaining part of his wish list.

When Senate Democrats wouldn’t accede to his demands, Mica refused to continue authorizing the agency and let the House adjourn without action. Again, the consequences to American citizens were considerable. Major parts of the FAA were shut down for several weeks, putting thousands of workers on furlough and requiring airplane inspectors to work without pay and cover their own travel expenses out of pocket in order to keep airplanes safe and flying. Around 24,000 construction workers lost their jobs, with many thousands of other jobs directly and indirectly lost, causing untold suffering and halting work at the peak period for construction of airport facilities, runways, hangars, and other operations. The urgently needed new generation of computerized air-traffic control lost critical weeks of development, and the FAA could not collect airfare taxes for several weeks, costing the federal treasury some $300 million. The savings Mica insisted upon by ending the subsidies to the small airports was a small fraction of that amount.

Ultimately, Senate Democrats accepted a short-term provision giving Mica some of what he wanted, but that was reversed under intense public and media pressure after the House returned and Mica gave in. But for weeks, one individual’s “my way or the highway” pique, framed in part as a fiscal conservative’s demand to cut out wasteful subsidies to underutilized rural airports, caused economic havoc way out of proportion to the magnitude of the problem and leading to a major increase in the deficit, instead of a consensual approach to reducing the subsidies. A somewhat chastened Mica, hurt by the wave of criticism, said defensively that he had just been trying to end business as usual. But if ending business as usual in Washington means adding to the debt and causing economic and social disruption in order to force a tiny sum in savings, it is not a desirable route to take.

In the past, tough negotiators who played hardball had a basic respect for their opponents and some sensitivity to the consequences of their tactics. They did not try gleefully to embarrass their counterparts in the other body or the other party to score political points, or push so far that the collateral damage of their actions truly hurt large numbers of Americans. Add to that the cynical exploitation of the rules to demolish the regular order in Congress and to damage policy deliberation in the service of the permanent campaign. That problem starts with the abuse of Rule XXII, the filibuster rule.3

The Senate is a slow-moving institution at its core, one that bends over backward to accommodate its one hundred oversized egos. Where the House is built around collective action, with rules to expedite it, the Senate is built around individual actors, with much of its ability to act requiring unanimous consent. Respect for the individual is one thing, but in recent years, the Senate has increasingly seen individual senators hold their colleagues and the larger government hostage to their whims and will. More and more, senators have blocked bills and nominations by the informal practice of the “hold,” basically an individual senator’s notification to the leadership in writing that he or she will object to consideration of a bill or nomination.

Because the individualized Senate operates mostly via unanimous consent to schedule and expedite its business, this practice has a significant effect. (The larger and more disciplined House operates by majority vote.) If any one senator denies that unanimous consent, it requires the majority leader to jump through many hoops and take much precious time to slate a bill or move to confirm a nominee. In past decades, when a senator invoked a hold to deny unanimous consent, the common practice was to allow an absent senator to delay deliberation on the bill or nomination until he or she could be there for the debate or vote, or to allow an unprepared senator to have the time to muster his or her arguments to debate on the floor, meaning a delay of a week or two. Holds, however, have morphed into indefinite or permanent vetoes, often done secretly, with members of each party using nominations as hostages to extract concessions from the executive branch.

We have seen outrageous examples of individual pique holding up dozens or hundreds of nominations. For example, in May 2003, then Senator Larry Craig of Idaho, trying to bludgeon the Air Force into stationing four cargo planes in his state, anonymously blocked all Air Force promotions for months until investigative reporters unmasked his secret hold. In February 2010, Senator Richard Shelby of Alabama put a blanket hold on all White House nominations for executive positions (over seventy were pending at the time) in order to get two earmarks worth tens of billions of dollars fast-tracked for his state. Before eventual confirmation, President Obama’s nomination for Commerce Secretary, California utility and energy executive John Bryson, was held up for months despite his sterling qualifications by a succession of Senate Republicans, leaving the Commerce Department leader less at a critical time. These tactics were not unprecedented. Democratic Leader Harry Reid in 2004 openly held up a number of appointments (he exempted military and judicial nominees) in order to get his nominee to the Nuclear Regulatory Commission approved. But blanket holds have become much more frequent and disruptive in the last several years.

The hold is in effect a threat to filibuster a bill or nomination. And the filibuster, the infamous process that requires a supermajority to overcome an intense minority in the Senate, can have profound implications for the ability to govern and to make policy. Here, the minority party’s sharply expanded use of the hold as a political tactic to delay and block action by the majority has transformed the Senate, especially over the past four years.

It is now ingrained as conventional wisdom that the filibuster and unlimited debate either are in the Constitution or have long been an integral part of the Senate. That assumption is wrong. The framers of the Constitution did not establish the basis for unlimited debate in the Senate, but senators introduced it in the first decade of the nineteenth century. The first Senates had the same provision as the House of Representatives, to allow a simple majority to stop debate and move to a vote, something called in parliamentary parlance “moving the previous question.”4

In an unintended quirk that changed history, Vice President Aaron Burr, in his 1805 farewell address to the Senate, suggested that it clean up its rule book, eliminating duplicative and extraneous rules, among them the previous-question motion. The Senate had no intention of allowing unlimited debate, but from that point on, any senator could take to the floor and hold it as long as he or she could stay there. It was several decades before any senator took advantage of the quirk, and even after, the move to block action by debating nonstop was rare.5 The lack of any rule or process to limit debate lasted until 1917, when a filibuster over efforts to rearm America in preparation for World War I by just five senators—an angry President Woodrow Wilson called them “a little band of willful men”—endangered American preparedness. That led to a backlash and a new rule allowing cloture—stopping the debate—if two-thirds of senators voting agreed. (The rule, XXII, stayed more or less intact until the 1970s, when the number required to stop the debate was reduced to sixty senators.)

Filibusters and their sister element, cloture motions to end debate and move to a vote, were extremely rare events after the advent of Rule XXII, but they carried with them an almost romantic notion of the power of individuals who feel intensely about an issue to grab the attention of the Senate and the country. Of course, the embodiment of that sentiment came in the 1939 movie Mr. Smith Goes to Washington, when Jimmy Stewart seized the Senate floor and spoke until hoarse and then until he collapsed, all in the name of ending the power of a corrupt political boss from his unnamed state.

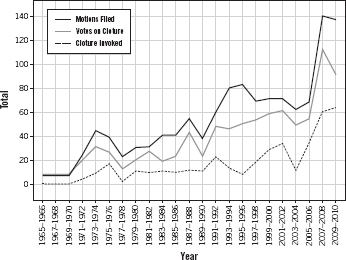

“Mr. Smith” was thoroughly fictional, and in the real world, attempts at filibuster and formal responses to them—meaning actual cloture motions to shut off debate—remained relatively rare, even during the civil rights era of the 1950s and 1960s. The number of cloture motions did increase after that, mostly because a handful of individual conservative senators, especially Democrat James Allen of Alabama and Republican Jesse Helms of North Carolina, seeing the role of Southern conservatives as a bloc decline, began to use more creative ways to gain leverage. This included finding ways to extend debate after a filibuster was invoked by offering hundreds of amendments and insisting on a vote on each. Still, even with Allen remaining active until his death in 1978, the average number of cloture motions filed in a given month was less than two; it increased to around three a month in the 1980s, jumped a bit in the 1990s during the Clinton presidency, and then leveled off in the early Bush years. But starting in 2006, this number spiked dramatically and even more with the election of Barack Obama.6 In the 110th Congress, 2007–2008, and in the 111th Congress, the number of cloture motions filed when the Senate was in session was on the order of two a week! (See Figure 3-1 for the number of motions from 1965 through 2010.)

The sharp jump in cloture motions came in response to the increasingly routine use of the filibuster. No longer is it just a tool of last resort, used only in rare cases when a minority with a strong belief on an issue of major importance attempts to bring the process to a screeching halt to focus public attention on its grievances. When Southern Democrats filibustered civil rights bills, they wanted to show their constituents and the broader American public why they were standing on the tracks to prevent the civil rights train from advancing and, in their view, destroying their way of life.

Now, since 2006, but especially since Obama’s inauguration in 2009, the filibuster is more often a stealth weapon, which minority Republicans use not to highlight an important national issue but to delay and obstruct quietly on nearly all matters, including routine and widely supported ones. It is fair to say that this pervasive use of the filibuster has never before happened in the history of the Senate.7

There’s no doubt that the increase in cloture motions is a two-way street, reflecting changes by both parties. The minority has moved to erect a filibuster bar for nearly everything. The majority has moved preemptively to cut off delays by invoking cloture at the start of the process, prior to any negotiations with the minority over the terms of debate, and to avoid politically charged amendments that might put some of their members in a difficult position back home by limiting the minority’s ability to offer amendments.8

Figure 3-1 Cloture Motions in the Senate, 1965–2010.

Invoking cloture means that sixty senators vote to stop debate and move to a resolution of the underlying bill or nomination (albeit after an additional sizable delay of at least thirty hours for additional debate). You might think that there would be a cloture motion only if a matter were so contentious that it deeply divided the Senate. But the increase in cloture motions in the past five years has been matched by an increase in their rate of success. Senators threatened filibusters or imposed holds on measures that were in fact not deeply contentious and controversial, but that easily passed the bar of sixty votes without any Mr. Smith–style filibustering on the floor. This is more evidence that senators have distorted a practice designed for rare use—to let a minority of any sort have its say in matters of great national significance—to serve other purposes. One purpose is rank obstruction, to use as much precious time as possible on the floor of the Senate to retard progress on business the majority wants to conduct, and to make everything look contentious and messy so that voters will react against the majority and against the policies the senators do manage to enact. These increased incentives for obstruction in the policy-making process are intimately tied to the intense competition for control of Congress and the White House.9

Consider three examples from the 111th Congress. The first is H.R. 3548, the Worker, Homeownership, and Business Assistance Act of 2009, pushed by the Obama administration and Senate Democrats, which moved to extend unemployment benefits during the deep recession. There was no opposition in the Senate to this bill; it would ultimately pass 98–0 in November 2009. But before then, minority Republicans mounted two filibusters, both on the motion to proceed to debate the bill and on its final passage. Each filibuster took two days before the Senate could bring up the cloture motion, and then another thirty hours each for postcloture debate. The senators adopted the first cloture motion 87–13; the second, 97–1.10 A bill that should have zipped through in a day or two at most took four weeks, including seven days of floor time, to be enacted.

Then there was the case of another slam dunk, H.R. 627, the Credit Cardholders’ Bill of Rights Act. Its purpose was, among other things, to limit usurious interest rates and exorbitant hidden charges. This bill ended up with only one cloture vote, after the filibuster on the motion to proceed was withdrawn. The cloture motion on passage of the bill sailed through on a vote of 92–2, and the bill passed by a 90–5 vote.11 But again, the clog in the process due to the filibuster threats and Rule XXII meant weeks of delay and seven days of floor time.

Our final example is the Fraud Enforcement and Recovery Act, S. 386, designed to increase criminal penalties for mortgage and securities fraud, among others. Once again, another futile filibuster, with cloture successfully invoked on final passage. The vote on the cloture motion was 84–4, on final passage, 92–4. This act took six days of floor time.12

These three noncontroversial bills passed with overwhelming majorities. A mere decade ago, they would have taken a grand total of three or four days to pass, including amendments. Now they take twenty days of precious and limited floor time, with the largest portion spent not on debating the merits of the bills or working intensively to improve them via substantive amendments, but on making action or progress on other bills more cumbersome and difficult. Because Rule XXII allows thirty hours of debate after cloture is successful, and because the rule does not require senators to actually be on the floor debating, Republicans have been able to insist on using the full thirty hours just to draw things out, not to debate a relevant issue. During those thirty hours, nothing of substance happens. Often, it’s just a mind-numbing calling of the roll after a senator notes the absence of a quorum—over and over again. This fits neither the intent of the rule nor the long-standing norms of the institution about what to do once a side has lost in votes on the floor—namely, accept defeat and move on to the next issue.

In another unfortunate use of the filibuster, senators have increasingly employed it to cripple presidents’ ability to fill executive and judicial branch positions.

Consider President Obama’s nomination of Judge Barbara Milano Keenan to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit. Judge Keenan’s qualifications were impeccable; as a judge on Virginia’s Supreme Court, she was widely praised. But her confirmation in March 2011 was subject to a filibuster and a cloture motion that passed 99–0, followed by a similar 99–0 confirmation vote. In the case of Judge Keenan, her confirmation occurred a full 169 days after her nomination, and 124 days after the Judiciary Committee unanimously reported her nomination to the floor.13 By our estimate, a process that the Senate could have handled in a few weeks, from formal nomination to committee hearing to confirmation, took almost half a year and wasted dozens of hours of floor time.

At least Judge Keenan’s nomination eventually made it to the floor. Senators have increasingly used holds, their ability to block consideration of a nominee indefinitely, as a broader partisan weapon to keep presidents from filling key positions, including many qualified and usually noncontroversial nominees.14 Here the focus, and damage, has been mainly on appellate judicial nominations (numbering roughly twenty-five to fifty per Congress) and the 400 or so Senate-confirmed senior positions in cabinet departments and executive agencies (excluding ambassadors) that serve at the pleasure of the president. In the case of the former, the confirmation process since the Clinton era has become increasingly prolonged and contentious. The confirmation rate of presidential circuit court appointments has plummeted from above 90 percent in the late 1970s and early 1980s to around 50 percent in recent years.

A particularly acrimonious confrontation over the delay by Democrats of several of President George W. Bush’s judicial nominations in 2005 led then Majority Leader Bill Frist to threaten use of the so-called “nuclear option”—a ruling from the chair sustained by a simple majority of senators to establish that the Constitution required the Senate to vote up or down on every judicial nomination (effectively, cloture by simple majority). Before the arrival of Frist’s deadline for breaking the impasse, a group of fourteen senators (seven Democrats and seven Republicans) reached an informal pact to oppose Frist’s “reform-by-ruling” while denying Democrats the ability to filibuster several of the pending nominations. This defused the immediate situation but did little to alter the long-run trajectory of the judicial confirmation process.

In earlier decades, senators almost always gave great leeway to presidents in picking judges, with disputes being the exception, not the rule, and most nominees being chosen because of experience and qualifications and with less regard for ideological purity. The Supreme Court through most of the twentieth century, up through the 1960s and into the 1970s, had many members who had served in elective office. Many, like Earl Warren or Hugo Black, had not been judges before their appointments. Often, as with Warren, their judicial opinions were in no way predictable from their previous jobs or statements. But as the political process became more polarized in the 1970s, 1980s, and beyond, judicial appointments also became more ideological and polarized, and more choices for the Supreme Court were appeals court judges, who had a lengthy record that made their likely opinions predictable going forward.

Lifetime appointments and the new, highly ideological stakes provided senators ample incentives to use holds and silent filibusters to prevent a majority of their colleagues from acting on judicial nominations, both to block those with different ideologies and to keep slots vacant until the presidency moves into their party’s hands. Along the way, judicial confirmations have become increasingly politicized, and delays in confirming appellate judges have led to increased vacancy rates that have produced longer case-processing times and growing caseloads per judge on federal dockets.

The process became acute when Republican majorities in the Senate during the Clinton presidency blocked not just liberals but moderate nominees for judicial posts. Democrats applied it in turn, albeit less aggressively, during the Bush presidency. But the process ratcheted up again with President Obama, and the conflict over appellate judges began to spill over to district court appointments, which are beginning to produce similarly low rates of confirmation. The current administration worsened its own problem with inexplicable delays at the beginning of Obama’s presidency in nominating candidates to fill a large number of judicial vacancies. But the senators’ aggressive move to use the hold and threat of filibuster to keep judicial vacancies open, with the hope that the slots will be available for the next president to fill, is the key phenomenon here.

Even more disconcerting has been the distortion of the confirmation process for executive nominees; the more it has become a political weapon, the less effectively presidents have been able to staff their administrations and run the government. As political scientist G. Calvin Mackenzie testified to the Senate Rules Committee in 2011, “We have in Washington today a presidential appointment process that is a less efficient and less effective mechanism for staffing the senior levels of government than its counter parts in any other industrialized democracy.”15 Some of the problem rests with administrations’ increasingly sclerotic nomination process. In an effort to do more thorough background checks to avoid ethical embarrassments, they are taking much more time vetting potential nominees before formally choosing them.

But the trends over the last four administrations place an increasing responsibility for delays on the Senate. The average time the Senate took to confirm nominees in the first year of new administrations has steadily increased (from 51.5 days under George H. W. Bush to 60.8 days under Barack Obama), while the percentage of presidential nominations it confirmed by the end of the first year declined (from 80.1 percent under George H. W. Bush to 64.4 percent under Barack Obama).16 These discouraging statistics actually understate the problem. The Senate usually confirms cabinet secretaries within a couple of weeks, while taking on average almost three months for top non-cabinet agency officials. The Senate has subjected some nominees to much more extended delays, leaving critical positions unfilled for much or all of a president’s first year in office. The effects reverberate: citizens offering to serve their country, often at significant personal and financial cost, are forced to put their personal lives on hold for many months. With the stress this puts on their careers, marriages, and children, will really talented people remain willing to subject themselves to such indignity? The government that we want to be more effective is crippled. Some cabinet secretaries have to manage with only skeleton senior staffs; a number, in office temporarily through recess appointments, have lacked the empowerment that comes with Senate confirmation. Recent administrations have many horror stories associated with the absence of timely confirmation of its top executives. And again, the amount of wasted time that the Senate could spend doing more productive things boggles the mind.

As Jonathan Cohn of The New Republic put it,

True, the constitution gives the Senate the power to “advise and consent” on executive branch appointments. And from the early days of the republic through the end of the 19th Century, the Senate and president fought regularly over the precise boundaries of that power—most famously when the Reconstruction Congress passed a law forbidding then President Andrew Johnson from removing a cabinet official without congressional permission. It was his decision to flout that law that drew impeachment and, very nearly, his removal from office.

But since that time the Senate has deferred more to the president on appointments, partly on the theory that a modern society needs a president who could staff the executive branch with like-minded officials. Although senators have frequently raised substantive and ideological objections to nominees, explicitly or implicitly, they did not engage in such wholesale, blanket opposition to appointments based (explicitly or even implicitly) on governing philosophy. As the Senate’s own website confirms, the Senate voted down nominations “only in the most blatant instances of unsuitability.” The obvious exception has been judicial appointments. But even those have increased dramatically in the last few years and, besides, those are lifetime appointments to an entirely separate branch of government.

What makes this ideological policing even more pernicious is the fact that it’s policing by a minority.17

A few recent examples drive home the cost of this folly. In mid- to late 2009, in the midst of the financial meltdown when critical decisions had to be made on the implementation of the Troubled Asset Relief Program (TARP), the Treasury Department had nominees for a slew of high-ranking policy positions twisting in the wind awaiting Senate confirmation. Treasury Secretary Tim Geithner had no deputy secretary, undersecretary for international affairs, undersecretary for domestic finance, assistant secretary for tax policy, assistant secretary for financial markets, assistant secretary for financial stability, and assistant secretary for legislative affairs. And the Senate has delayed other economy-related positions, some for as long as a year or more, at a time when the economy continues to struggle. Testifying in 2011 before the Senate Banking Committee, Sheila Bair, the outgoing chairwoman of the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC), a key figure in the ongoing banking crisis, warned of significant risk to the financial system posed by the failure to approve qualified candidates for posts at the FDIC, Treasury, and Federal Housing Finance Agency—not to mention the new Consumer Financial Protection Bureau.

Early in the Obama administration, there was a long list of other critical positions with urgent responsibilities that waited for months without a vote in the Senate to fill them. They included the commissioner of U.S. Customs and Border Protection, director of the Transportation Security Administration, head of the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, and director of the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (more about this later). While in some of these instances, the delays occurred for legitimate reasons, in the overwhelming majority, they came down to either ideological and partisan battles in the Senate or the personal agendas and vendettas of individual senators. In every instance, the senators ignored the need to put people in place to run agencies and solve national problems.

Currently, because most holds remain secret at the request of individual senators, there is no foolproof way we can discern how many nominations are subject to holds. We can, however, examine the list of nominations that committees have approved and placed on the Senate executive calendar. We presume that absent a hold or other signal of a filibuster, the Majority Leader will move expeditiously to call up these nominations. Not long ago, it was rare that nominees would linger on the list of pending confirmation for days, weeks, and months. On Memorial Day, 2002, during George W. Bush’s administration, thirteen nominations were pending on the executive calendar. Eight years later, under Obama, the number was 108.18

Republicans’ efforts in the tacit cause of partisan rivalry to block the confirmation of nominees—to embarrass the president and hobble his ability to run the executive branch—are troubling enough. But the new strategy has an additional, even more disturbing element: blocking nominations, even while acknowledging the competence and integrity of the nominees, to prevent the legitimate implementation of laws on the books. In many cases, if no person is running an agency charged with enforcing a law, the agency can’t easily implement or enforce the law; career bureaucrats are reluctant to make critical decisions without the imprimatur of the presidential appointee who should be running the agency. We call this—together with other tactics, including repeal of just-enacted statutes, coordinated challenges to their constitutionality, and denial of funds for implementation—the new nullification, in reference to the pre–Civil War theory in Southern states that a state could ignore or nullify a federal law it unilaterally viewed as unconstitutional.

President Obama’s nomination of Donald Berwick to run the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, the agency primarily responsible for implementing the Affordable Care Act, or health-care reform, may have started the trend. While some during Berwick’s confirmation hearing made charges questioning his judgment in such areas as the effectiveness of Britain’s health-care system, no one questioned his qualifications or integrity. But Republican Senate leaders threatened to filibuster his nomination, forcing President Obama to make Berwick a recess appointee with a limited term and with significantly limited clout compared to Senate-confirmed administrators. A widely respected scholar and practitioner whose career had been focused on ways to reduce health-care costs without harming patients, Berwick was a nearly ideal choice for the job. There is no plausible reason for the threats of filibuster other than the Republicans’ attempt to hobble the new health-care program. When Berwick announced his resignation right before the end of his recess appointment, the Daily Caller, a conservative website, wrote, “Earlier this year, 42 Republican senators promised to block Berwick’s confirmation. Their success in preventing Berwick’s appointment represents another blow to the president’s health care law—Berwick was an important actor in introducing its reforms.”19 The result has effectively retarded or bollixed up the implementation of a law enacted by elected officials.

The blocking strategy continued with Peter Diamond, a Nobel Prize–winning economist at MIT, nominated for a seat on the Federal Reserve Board, who was also stymied by a party-led filibuster. Then, even more troubling, the Senate Republican leaders declared that they would block confirmation of any nominee, no matter how distinguished or qualified, to head the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) created by the Dodd-Frank financial regulation reform act, unless the administration agreed to change the structure of the agency specified in the law. Having lost that legislative battle when the Dodd-Frank bill was enacted, they now insisted that a key provision be altered before they would allow the CFPB to exercise its statutory authority. Republicans used the threat of filibuster to block Elizabeth Warren, a Harvard Law School professor and the intellectual parent of the CFPB, from consideration for the position. So President Obama turned to Richard Cordray, a former Ohio attorney general. At his confirmation hearing in July 2011, Republicans on the Senate Banking Committee praised his background, character, qualifications, and family, before making it abundantly clear that he would not be confirmed because they do not like the law. Then, adopting and expanding a practice initiated by Majority Leader Reid at the end of the Bush administration, Republicans refused to allow the Congress to recess at the end of 2011. They insisted on a series of “pro forma” sessions every three days, with only a single member present, to deny the president the ability to make any recess appointments. President Obama, drawing on legal advice first offered by the Office of Legal Counsel in the Bush administration and reinforced by his own legal advisors, insisted that his constitutional authority to make recess appointments could not be abrogated by such means and appointed Cordray to head the CFPB, albeit with a shorter duration and lesser legitimacy than a regular Senate confirmation would provide.

Whether lawmakers like or dislike laws, they are under oath to carry them out. They can move, under their Article 1 powers, to repeal the laws, amend the laws, or even cut off funding for them, subject to the checks and balances otherwise in the Constitution. And, of course, they are free to run in the next election against those laws. But to use the hold and filibuster to undermine laws on the books from being implemented is an underhanded tactic, one reflecting, in our view, the increasing dysfunction of a parliamentary-style minority party distorting the rules and norms of the Senate to accomplish its ideological and partisan ends.

Holds, filibusters, and other delay and obstruction tactics have been around since the beginning of the republic. But as we look at the panoply of tactics and techniques for throwing wrenches and grenades into the regular order of the policy process, which the new and old media’s outside agitation encourages and even incites, we do not see business as usual. The target is no longer an individual judge or cabinet member hated for a real or imagined ideological leaning. The pathologies we’ve identified, old and new, provide incontrovertible evidence of people who have become more loyal to party than to country. As a result, the political system has become grievously hobbled at a time when the country faces unusually serious challenges and grave threats.

The single-minded focus on scoring political points over solving problems, escalating over the last several decades, has reached a level of such intensity and bitterness that the government seems incapable of taking and sustaining public decisions responsive to the existential challenges facing the country. The public may still revere the Constitution and support the system of government that it shaped, but this is more a measure of patriotism—love of country and pride in being an American—than of satisfaction with how it is working in practice. All of the boastful talk of American exceptionalism cannot obscure the growing sense that the country is squandering its economic future and putting itself at risk because of an inability to govern effectively. This is a time of immense economic peril, with the global economy at risk, sustained unemployment that can hollow out the work force in the future, a lack of any long-term fiscal policy that can be enacted, and the need for action in areas from climate change to immigration.

We believe a fundamental problem is the mismatch between parliamentary-style political parties—ideologically polarized, internally unified, vehemently oppositional, and politically strategic—that has emerged in recent years and a separation-of-powers system that makes it extremely difficult for majorities to work their will. Students of comparative politics have demonstrated that the American policy-making system of checks and balances and separation of powers has more structural impediments to action than any other major democracy.20 Now there are additional incentives for obstruction in that policy-making process. Witness the Republicans’ immense electoral success in 2010 after voting in unison against virtually every Obama initiative and priority, and making each vote and enactment contentious and excruciating, followed by major efforts to delegitimize the result. And because of the partisan nature of much of the media and the reflexive tendency of many in the mainstream press to use false equivalence to explain outcomes, it becomes much easier for a minority, in this case the Republicans, to use filibusters, holds, and other techniques to obstruct. The status quo bias of the constitutional system becomes magnified under dysfunction and creates a take-no-prisoners political dynamic that gives new meaning to the late Daniel Patrick Moynihan’s concept of “defining deviancy down.”21

The dysfunction that arises from the incompatibility of the U.S. constitutional system with parliamentary-type parties is compounded by the asymmetric polarization of those parties. Today’s Republican Party, as we noted at the beginning of the book, is an insurgent outlier. It has become ideologically extreme; contemptuous of the inherited social and economic policy regime; scornful of compromise; unpersuaded by conventional understanding of facts, evidence, and science; and dismissive of the legitimacy of its political opposition, all but declaring war on the government. The Democratic Party, while no paragon of civic virtue, is more ideologically centered and diverse, protective of the government’s role as it developed over the course of the last century, open to incremental changes in policy fashioned through bargaining with the Republicans, and less disposed to or adept at take-no-prisoners conflict between the parties. This asymmetry between the parties, which journalists and scholars often brush aside or whitewash in a quest for “balance,” constitutes a huge obstacle to effective governance.

Bringing the Republican Party back into the mainstream of American politics and policy and return to a more regular, problem-solving orientation for both parties would go a long way toward reducing the dysfunctionality of American politics. Yet it would not magically return America and the American political system to a golden era. The other changes we have begun to outline, including the profound changes in the mass media, the coarsening of American culture, the populist distrust of nearly all leaders except those in the military, and the insidious and destructive role of money in politics and policy making, would still be in place, making problem solving all the more vexing. As we continue to analyze the impact of this dysfunction, we will focus on new ways to ameliorate these broader problems as well.