Expensive medicines are always good: if not for the patient, at least for the druggist.

—RUSSIAN PROVERB

“Could you say that again?” Heather managed to croak weakly.1 What she thought she heard had so stunned her that she was surprised she could produce any sound at all. Robin, the benefits manager, hesitated a moment before replying. “I said that despite the changes to the insurance plan, your medication costs will continue to be covered. However, there is a deductible, and you will be responsible for the out-of-pocket costs of your medication until the deductible is met.”

“And the deductible is $2,500?” demanded Heather incredulously. Not waiting for an answer, she continued, “So I have to pay for my meds until I have bought $2,500 worth?”

“Yes.”

Heather, thirty-five, knew she should be angry. And scared. “But the truth is, it just didn’t sink in for a while. I was in shock. I had walked into the HR conference room for what I thought would be a routine benefits meeting and I was going to leave not knowing how I would pay for my pills. I felt clueless and confused. But I knew I needed my medication.” Her medication is called Mysoline, and Heather needs it to function because she suffers from epilepsy. She is also a strong, vibrant woman who runs half-marathons, volunteers at a food bank, and holds down a high-energy position as a publicist for a small New York City publisher.

But she well remembers being a delicate child beset by allergies and racked by frequent seizures until a doctor finally discovered that Mysoline quelled them without triggering her numerous sensitivities. For twenty-four years she has never missed a pill or a doctor’s appointment, and she has been rewarded with a seizure-free life.

Suddenly, Heather felt that she couldn’t leave the meeting without pressing her case. “You can’t do this to me. Twenty-five hundred dollars—I don’t—how many people have that kind of money lying around? I can’t afford this. You’re putting my health in danger, I cannot function without Mysoline.” The benefits manager began to repeat the new policy, but Heather interrupted her. “I understood what you said. Did you hear what I said? Without my pills, I will have seizures. I can’t work. I can’t function.” Swallowing, she fell silent for a moment before pleading, “Please don’t do this to me.” Uncomfortable, Robin stared at the sheaf of papers before her, fingering them as if the answer were written there somewhere. “I am afraid …” she began, but didn’t finish.

Instead, she looked into Heather’s eyes. “Heather, my hands are tied. We have to cut costs, and we don’t want to lay anyone off. This is the best we can do. Can’t you borrow the money?” Heather looked down and shook her head back and forth, not trusting her voice.

“Does anyone else have questions?” Robin asked the room. “No? Well, feel free to call me for a meeting if you need more information.” As the group filed out of the room, Robin turned to Heather, who was still sitting silently. “Let’s go to my office. I think we can arrange a loan with liberal terms. I’ll do what I can to help you get through this.”

After receiving the bad news in January 2008, Heather quickly discovered that area pharmacies sold the 250 mg Mysoline tablets she needs only in a three-month supply, for $1,200, which she had to borrow. After that, she ordered a one-month bottle online. But

Suddenly, I couldn’t find the formulation I needed online, or anywhere else. I called a woman at the insurance company, MedCo, and she was great, very helpful. She would find a pharmacy in the New York City area that carried it, call to tell me, and I would drive over and buy up all they had because I was so afraid of running out. Once I drove to Oceanside in Queens to buy it, then to a pharmacy in Howard Beach where they said they had ordered it for me but I had to buy the entire bottle at $700, which I did and finally satisfied the $2,500 deductible. But one day in June I called MedCo and they could not find a pharmacy that carried it anywhere. I called the drug’s maker in California and the representative informed me in a casual voice that they had stopped manufacturing it and he didn’t know if or when it would be back on the shelves. He said it like he was saying “It’s sunny outside.” He also said something about it being off-patent or the patent changing hands; I was so nervous, I don’t remember. I asked, “What am I supposed to do? I need it,” and he said airily, “Oh, there must be a generic.” No, he didn’t know the name. No, he didn’t know where I could get it. No details or advice: that was it.

Now I was really scared. I couldn’t take just any anticonvulsant: I’m allergic to Dilantin and can’t take phenobarbital. Mysoline allows me to function: without it, I would be seizing. What if there wasn’t a generic? If there was one, what if some “inert” ingredient in the generic triggered an allergy?

Mysoline is branded but off-patent. Heather’s doctor found that there is a generic version, but warned that she wasn’t out of the woods yet. “My doctor is convinced that Mysoline is superior to primidone, the generic version, and he was concerned that the generic could cause me trouble or work less efficiently. He says that generics have quality issues and are not always the same as the branded versions.”

Heather’s doctor is correct in saying that generics and patented medications can differ. Generic medications can be made and sold without patent protection because the formulation of the generic drug may be patented, but its active ingredient is not, opening the door to equivalent formulations and market competition that usually reduces the U.S. price dramatically, by at least 20 percent. Although generics must be “bioequivalent,” with the same active ingredients and exerting the same effects, the “identical” description used by the FDA to describe generic versions of drugs is more a legal label than a scientific one, because generics can diverge from patented drugs in their dosages, administration, and even formulations. In Heather’s case, her doctor performed repeated blood tests and found that the generic worked for her, fortunately without triggering any of her allergies.

“Then,” Heather recalled, “in the summer of 2009, the company called to tell me that the medication would be back on the shelves in mid-July. I was glad to get it, but I resent the indifference that the drug maker and my employer showed toward my life and health.” Although Heather suffered no physical harm from her ordeal, it has changed her outlook. “This wasn’t elective; this was a necessity, and I was shaken to think that my medical lifeline could be snatched away just like that. I don’t think I’ll ever see drug companies the same way again.”

Mysoline, Heather’s medical lifeline, is not a novel “blockbuster”—usually defined as a drug with annual revenues of over $1 billion. Mysoline is not even very profitable despite its substantial price tag, because relatively few people buy it. It is an unfashionable drug introduced in 1950 by a company that is now known as AstraZeneca, and it is now used by a small minority of people with epilepsy. In the decades since Mysoline’s advent, it has been surpassed by many more modern anticonvulsives, although it is less toxic and triggers fewer side effects than most newer drugs. Doctors long ago fell out of the habit of prescribing it, and most who take it are older people who resist changing a medication that works for them or people who, like Heather, cannot tolerate the contemporary drugs.

It went off-patent a long time ago and several drug makers have manufactured and distributed generic forms of the drug that compete with Mysoline for its shrinking market. By 2009, Valeant was making Mysoline in the 250 mg formulation Heather needs; it had vanished from store shelves in 2008 after its previous maker determined that it failed to meet “certain commercial criteria.”2 It simply wasn’t profitable enough.

But its sudden, unannounced withdrawal had put Heather and others who depend on it at risk for more than isolated seizures: as its label clearly warns, abruptly discontinuing Mysoline can cause status epilepticus, a life-threatening condition in which the person’s body is racked by repeated, frequent seizures that can kill.

At first blush, one may be tempted to brush aside complaints about profit-driven marketing decisions and argue that a nongovernmental for-profit company has the right to abandon any product that fails to meet its commercial criteria. Ours is an unapologetically capitalist society, and “profit” is not a dirty word. Pharmaceutical corporations are entitled to profit by patents on medications that help us live longer, happier lives—and by other kinds of medications, if they can legally sell them. But Dr. Eva C. Winkler, an oncologist and expert in the organizational ethics of health care, points out that there are ethical and legal limits to profit making in health-care settings. “In a healthcare organization, competence is ensured by setting high standards, promoting continuing professional development, tying incentives to quality of care rather than to costs alone [italics mine], and ensuring adequate staffing.”3 Heather’s situation dramatizes the toxic economy and ethical morass that sometimes result from exploiting patents that are key to health rather than placing quality of care ahead of profits.

In the absence of sufficient countervailing factors, the weighing of profits over patient welfare has generated a host of such real, not philosophical, American nightmares. They arise partly because the U.S. government allows drug companies to set prices without the regulation and controls employed by some countries, such as Brazil and Canada.

Happily married and with three children aged six to eleven, John Colacci thought of himself as a blessed man. He was supported by an extended family, many friends, and a can-do attitude as he stood before a packed ballroom at a 2001 colorectal-cancer fund-raiser in Toronto. There, he quoted Eleanor Roosevelt: “Yesterday is history; tomorrow is a mystery. Today is the gift: That’s why it is called ‘the present.’ ”

The fund-raiser was held to raise money to offset the considerable medical expenses of cancer patients like himself. “None of us knows for sure how long we have to live,” he continued, “but we always have a choice how we spend our time in the present moment.” In 2004, however, Colacci learned that he was running out of time: the Avastin he had been taking since his cancer recurrence had stopped working, and the statistics gave him just 4.6 months to live.

As he anxiously researched his treatment options, Colacci learned that Erbitux, a last-ditch medication for metastatic colorectal cancer, existed, but not for him. (If Erbitux sounds familiar, this is because it is the drug that led to Martha Stewart’s jailing over insider trading in 2004: ImClone, the biotechnology company that developed it, was founded by her friend Sam Waksal.) Erbitux helps many cancer patients who do not respond to other medications,4 but Bristol-Myers Squibb (BMS) had decided not to launch the drug in Canada because it could not charge a high-enough price there.

In 2004, Erbitux cost $17,000 a month, making it one of the most expensive cancer drugs. Moreover, it treats colorectal cancer, which strikes 106,000 Americans a year. But it was not the costliest cancer drug by a long shot: Zevalin treatments for an unusual type of lymphoma cost $24,000 a month. By contrast, the Avastin that Colacci had been taking was a relative bargain at C$4,000 a month.5

BMS decided to shun the Canadian market, which has long been a thorn in the side of the drug industry because it flatly refuses to pay top dollar for the pharmaceuticals it buys to distribute through its governmental health services. Instead, its Patented Medicine Prices Review Board assesses a drug’s cost in Germany, France, Italy, Sweden, Switzerland, the United Kingdom, and the United States, then applies a formula to ensure that Canada pays something near the list’s median. For many years, this strategy guaranteed that Canadians’ medications cost less than those in most other affluent Western nations, including the United States.

Recently, however, drug makers have reacted by playing hardball and refusing to sell their medications in Canada at all—in essence, holding Canadian patients hostage for a higher price. Because Erbitux was protected by patent, no other company could legally offer it for sale without a license from BMS, leaving patients like Colacci without access to the drug.

So Colacci turned to the United States. During the Erbitux standoff, Canada spent $208,125 within a year in order for him to cross the border and undergo weekly treatments with the U.S.-licensed drug at the Roswell Park Cancer Institute in Amherst, New York. Colacci was lucky: some other Canadians had to pay similar sums out of pocket.

Was the drug effective? “I got fabulous results from it,” Colacci, forty-three, exulted in 2008. “It literally melted it [the tumor] away.”

Bristol-Myers Squibb finally relented and decided to sell Erbitux to Canadians at their government’s price—a hefty $56,000 for the average course of therapy—high, but considerably lower than what the Canadian government had paid for Colacci’s U.S. drugs, and lower than what we pay in the United States. However, E. Richard Gold, director of McGill University’s Centre for Intellectual Property Policy, sees this less as a happy ending than a cautionary tale. “Both the Commissioner of Patents and the Competition Bureau should be prepared to step in to prevent such abusive behavior in the future.”

John Colacci died surrounded by his family on Thursday, June 18, 2009, at the age of forty-four. Was the Erbitux worth the astronomical price? Perhaps a better question is, “Why did it cost $208,000?” This is not an isolated case: cancer medications tend to be very expensive, and there are eight such medicines for which Americans pay more than $200,000 annually, as well as three others that cost in excess of $350,000 a year.6 A slew of other cancer drugs are just as expensive per dose, but they are typically taken for less than a year and so never top the annual price tag of the other medications. Some common but relatively pricey medicines include Lipitor, which lowers blood cholesterol and costs $1,500 a year, and the schizophrenia drug Zyprexa, which costs $7,000 a year.

Why do our medications cost so much—too much—and how can we change this sorry situation?

Pharmaceutical companies, principally represented by PhRMA, the Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America, don’t deny that their prices are high: pharmaceutical firms claim that high prices are necessary to recoup their gigantic investments in developing patented medicines. Defending and profiting from their patents, they argue, is also necessary to protect their investment. After the USPTO issues patents for a company’s medicines, genes, cell lines, genetically tailored animals, or other medically valuable inventions, the company can realize profits only by exploiting that exclusive patent. Companies also say they depend upon profits to provide funds that underwrite additional research and more medicines, so that research into new cures would grind to a halt if prices were lowered.

The companies add that they need their patents to protect their huge investment in research and development from interloping competitors who, were it not for patents, could simply reverse-engineer, reformulate, and offer the medications for sale on the cheap because they would not be saddled with the considerable expenses involved in research, development, and FDA-required clinical testing.7

Thus, drug makers offer rationales for prohibitive pricing, claiming that they need to charge high prices in order to fund the risky, expensive, and lengthy business of bringing medications to market that fight important diseases while extending the lives and alleviating the sufferings of Americans. As PhRMA states on its website:

It takes about 10–15 years to develop one new medicine from the time it is discovered to when it is available for treating patients. The average cost to research and develop each successful drug is estimated to be $800 million to $1 billion [italics mine]. This number includes the cost of the thousands of failures: For every 5,000–10,000 compounds that enter the research and development (R&D) pipeline, ultimately only one receives approval.… Success takes immense resources.8

The $800 million figure quickly became ubiquitous, cited even in a 2010 entry on the World Records Academy website:

MOST EXPENSIVE MEDICINE—

WORLD RECORD SET BY SOLIRIS

CHESHIRE, CT, USA—Soliris, a drug made by Alexion Pharmaceuticals, which is given intravenously to treat a rare disorder [paroxysymal nocturnal hemoglobinuria] in which the immune system destroys the red blood cells at night, costs $409,500 a year—setting the world record for the most expensive medicine.…

Alexion spokesman Irving Adler said the high price of Soliris reflects several factors, “including an $800 million investment to develop the drug,” as well as a 15-year investment of time.…

Last year Soliris sales were $295 million. Since Alexion started selling Soliris two years ago, its stock price is up 130%.9

(Moreover, in 2009 PhRMA agreed with an upward revision of the estimated cost of bringing a new drug to market, to between $1.3 billion and $1.7 billion. The study methodology was very similar to that of the 2001 study and shared its flaws, which are detailed below.)10

Does it really cost more than $800 million to create a new drug? In 2001, Joseph A. DiMasi, now director of economic analyses at the Tufts University Center for the Study of Drug Development, partnered with the University of Rochester to calculate the answer: each new drug for the U.S. market takes twelve to fifteen years and costs $802 million,11 a price that has doubled since 1987.12

The Tufts study was based on a survey of ten pharmaceutical companies and on information supplied by PhRMA. The confidential data provided by the companies to Tufts included several categories of research expenditures used to calculate the cost of bringing a single drug to market. These included the costs of research and the profits the drug makers could have realized by investing their money elsewhere than drug design and testing.13

PhRMA praised DiMasi’s study and verified the accuracy of its findings, constantly citing the $802 million figure—often rounded down to $800 million—in its publications and in interviews that defended high drug prices. But Clay O’Dell, a spokesperson for the Generic Pharmaceutical Association, was less impressed: “The methodology of this study is suspect. It ignores the fact that some of the drug development costs are tax deductible, and that some of the research is subsidized by the government through the National Institutes of Health.” In fact, a U.S. government study just the year before had determined that a new drug took from ten to twelve years to come to market, at a cost of $359 million—less than half that alleged by the Tufts study.14

From the beginning, independent expert analysts had wished to scrutinize the study’s data, but they went unexamined by outsiders for nearly a year because the Tufts analysts did not release the data on which the authors relied. The individual pharmaceutical companies that had supplied data insisted that their numbers were proprietary—industry secrets—and successfully fought their release to these independent evaluators.

Over the next year, the $800 million figure remained unchallenged as analysts unsuccessfully sought to force the release of the proprietary data on which it was based. During this time the report’s numbers were widely accepted and had gained currency among the public as well: a surprising number of people can cite the $800 million estimate.

Drug makers certainly can—the gargantuan price tag forms the backbone of their rationale for high prices. The industry complains that R&D is so very risky that only one in a thousand candidate drugs ultimately finds its way to pharmacy shelves and profitability. Because most medications fall by the wayside during research and development, industry earnings must cover the cost of these failed drugs as well as that of the relative few that become profitable.

The DiMasi report also claims that conducting clinical trials, which generate up to 70 percent of the high R&D bill, costs $282 million per new drug.15 But this figure far exceeds that arrived at by the Congressional Research Service, and it also outstrips the 29 percent figure in PhRMA’s own 1999 survey.16 However, the purportedly high cost of clinical trials not only feeds the purported $800-million-per-drug price tag, it gives the industry a useful basis for lobbying the FDA to ease and speed up the drug-approval process.

The drug companies marry the claims of the hefty price of a new drug to a warning that if they do not earn enough to recoup the staggering price of drug development, the pipeline of needed new drugs for major medical problems will dry up and the American public will face a dearth of the medicines that keep us alive and healthy. Industry analysts argue that because a patent confers a twenty-year monopoly from the date of application and a new medication takes as long as fifteen years to develop, test, and bring to market, the company that holds the medication patent has as little as five years to exploit that patent and recoup these stratospheric costs, to say nothing of earning a profit.

These claims are studded with factual and logical flaws that cause a dramatic overestimation of medications costs. Many of these issues are detailed in financial writer Merrill Goozner’s revelatory book The $800 Million Pill: The Truth Behind the Cost of New Drugs.

Among the flaws in the Tufts study:

Instead of a broadly representative sampling of drugs, the Tufts study confined itself to pricing a narrow, atypically expensive selection of drugs that it called “self-originated new chemical entities.” These are more commonly called “new molecular entities,” or NMEs, and they are the rarest type of medication in that they represent a completely novel treatment for disease, rather than a “retread” of existing medications. Over the twelve-year period preceding the Tufts study, only 42 percent of new drugs were NMEs, and only about twenty-six such drugs enter the global market each year.17

By contrast, most drugs that appear on the U.S. market today are slightly modified versions of existing drugs, popularly called “me too” or “copycat” drugs. They are created by tweaking the molecular structure of FDA-approved drugs to produce a closely related drug with similar effects. Or the “new” drug is chemically unchanged but released on the market in a different strength, or reformulated as extended-release pills, syrups, or inhalants. Alternatively, medicines are paired with other drugs, as when Claritin was combined with the decongestant pseudoephedrine to create Claritin-D, which does double duty by treating people who suffer from allergies and colds. A drug may also be turned to novel uses, as when Prozac was “repurposed” as Sarafem for menstrual symptoms. All win fresh patents for the firm and are sold as expensive “new” drugs.

Such doppelgänger drugs rarely meet a new medical need: they are routes to obtaining new patents or other monopolies on existing drugs, and, unlike NMEs, they are familiar, predictable, and relatively cheap to formulate and test.

But NMEs are much more difficult to discover, formulate, and test than are the “copycat” drugs that have come to flood the market, so they are also the most expensive. This leads us to the next of the study’s distortions.

Not only did the Tufts calculation include only the atypical, expensive NMEs, it focused on the rarest, costliest kind—the drugs whose development and testing costs are borne wholly by the pharmaceutical industry. Not one of the sixty-eight drugs in the study was developed with any kind of government financial support, which is very unusual.

Government-funded academic researchers are usually responsible for the discovery and innovation that the pharmaceutical industry has capitalized. The early development costs of most drugs are borne by the government, which subsidizes university and other public research through grants. Biotechnology companies tend to develop the university’s government-supported drug discoveries, and then the biotechs partner with or are purchased by large pharmaceutical companies. Thus the drug firms acquire the medication and the patent without paying for the taxpayer-subsidized research.

Dennis Slamon of UCLA discovered Herceptin, which staves off breast cancer recurrence; Craig Jordan of Northwestern University developed tamoxifen, also for breast cancer, and Brian J. Druker of Oregon Health and Science University shepherded kinase inhibitors, which offer tailored, focused attacks on cancer cells rather than the more diffuse attacks that also ravage healthy tissue. One such kinase inhibitor, Gleevec, is the most effective cancer treatment for chronic myeloid leukemia, a surgical strike that was developed in academia. Entire families of essential medications, such as protease inhibitors for HIV/AIDS, were discovered and initially developed in academia, not in corporate laboratories.

During the period of the Tufts study, the U.S. government spent close to $10 billion supporting the academic development of drugs, twice as much as industry did.

DiMasi found that the average price of developing an atypical NME drug without any government support totaled approximately $400 million. But he then added an additional charge that more than doubled the figure, to $802 million. That charge is the “opportunity cost.”

John Stuart Mill introduced the concept of an opportunity cost as the cost of what one surrenders in one direction in order to pursue an investment in another. Investing in one arena, such as drug design, precludes spending those funds elsewhere, so you lose the benefits posed by the other opportunity. If, for example, I use $10 to buy a movie ticket instead of depositing the cash in a savings account, the opportunity cost is the interest I would have earned from the $10. If I wait a few years to apply the opportunity cost, the interest rate will increase its value. If I wait long enough to calculate it, the value of the interest on that $10 in forsworn savings will double it to $20. The fact that I also could have doubled it in an hour by playing bingo cannot enter into the calculations, because although there may be more than one alternative way to spend the funds in question, warns Goozner, the opportunity cost is always the value of one choice, not all of them.

Similarly, if a pharmaceutical company spends, say, $240 million developing a new drug instead of banking the funds, the opportunity cost is the interest it would have earned had it made that deposit. Or the opportunity cost can be the dividends the firm would have earned had it bought stock in Starbucks instead. Or it can be the warm sense of altruism, elevated self-esteem, and glowing corporate image the firm would have basked in had it donated the same funds to global hunger relief, because an opportunity cost needn’t be limited to money. But in this case concerning drug-development costs, money is what is at stake.18

In their study, the Tufts analysts decided that the opportunity cost was the loss of the investment income that drug makers could earn if they invested their funds instead of dedicating them to the search for new drugs. This cost is usually assessed some time after the research is complete, with interest. Because DiMasi included opportunity costs and added them only some time later, after they had accrued value with interest, the value of the opportunity costs approximately doubled his estimate of drug-development costs.

Although the accounting firm Ernst & Young validated this cost for the Tufts team, Goozner points out that applying the opportunity cost contradicts generally accepted accounting practices. For a drug company, drug research is not an investment; it is a business expense. If drug companies invested their resources in Starbucks or in global hunger eradication instead of drug design, they would no longer be drug companies. Expending resources on drug design and marketing is not an option for a drug company; it is a necessity.

This means that, for tax purposes, the expenditure on drug design is a business deduction, not an investment. Opportunity costs simply do not apply, and most independent drug-firm studies recognize this. In fact, only two of the seven studies that the Tufts report references include an opportunity cost. This cost does not properly apply here, and it should not have been part of these calculations, slashing the $802 million price tag roughly in half, to $403 million.

Pharmaceutical companies receive more tax deductions than any other industry: in fact, after tax benefits are applied, the real expense to the industry of each R&D dollar spent is only $0.66.19 When these tax breaks are applied to the per-drug cost calculations, the cost is further reduced, from $403 million to $240 million.20

By DiMasi’s own estimates, the cost of conducting clinical trials of drug candidates constitutes 70 percent of the cost of bringing a new drug to market. But this is only because clinical trials conducted by the drug industry carry an unusually high price tag, much higher than comparable ones conducted by the government.21

The National Institute of Allergies and Infectious Diseases, or NIAID, for example, spent $1.5 billion to conduct 1,700 clinical trials between 1992 and 2001. The agency had to pay for the studies and also for the treatment, care, and testing of one hundred thousand volunteers. The Government Accounting Office found that the average extra cost of maintaining a patient in their clinical trials of an experimental therapy was only $750 more than maintaining him on standard therapy.

In clinical trials conducted by private industry, however, the average additional cost was $2500. This inflation leads some analysts to cry “foul” and to wonder why drug firms pay so much more for clinical trials.

Moreover, a strange practice inflates the cumulative cost of the drug industry’s clinical trials. Pharmaceutical companies claim that they must spend a great deal of money to test candidate drugs for FDA approval, but many of the medications in their clinical trials do not require testing or approval, because they have already been FDA-approved for the indication in question. A CenterWatch study determined that in 2000, the industry spent $1.5 billion on clinical trials of drugs that had already been approved.

Why? Because industry’s clinical trials include “seeding” trials, in which pharmaceutical sales representatives induce doctors to prescribe a drug to a large number of patients. The resulting data are collected and exhaustively mined by the company for any positive results that can be used in marketing, advertising, and “physician education” about the product.

Similarly, in “switching” trials, large numbers of doctors are induced to change their patients to another medication—that of the company conducting the trial—and the data are scrutinized for any impressive-sounding results. Seeding and switching studies are not conducted for FDA approval, but in order to increase the marketing, visibility, and sales of medications. These clinical trial data are used by sales representatives in persuading doctors to use the drugs, to replace other firms’ drugs with the one being studied, or to use the tested drug for a different indication. Such trials often lack a control group, are sloppily designed, or otherwise fail to meet FDA standards, but they are useful for spurring sales.22

Bristol-Myers Squibb, for example, like many other major firms, produced an FDA-approved statin drug (also known as an HMG-CoA reductase inhibitor). Statin drugs include Mevacor, Lipitor, Zocor, Pravachol, Lescol, and Crestor, which reduce blood cholesterol, a waxy substance that is associated with heart attacks, stroke, and other cardiovascular diseases.23 BMS amassed clinical data from seeding and switching trials to convince doctors that its statin drug works better than Merck’s, even though the BMS drug lowered cholesterol less. BMS spent tens of millions of dollars and emerged with data that might not have stood up to FDA review but was invaluable for pitches to doctors, public relations, press conferences, marketing—and for inflating the average R&D cost.

Appalled, the editors of thirteen medical journals united to write a New England Journal of Medicine editorial that condemned this practice.24 “Patients participate in clinical trials largely for altruistic reasons, that is, to advance the standard of care,” it read. “In the light of that truth, the use of clinical trials primarily for marketing in our view makes a mockery of clinical investigation and is a misuse of a powerful tool.”25

Such seeding and switching trials should not have been included in the price of bringing a drug to pharmacy shelves.

Thus, Goozner calculates that even when it includes the inflated costs of irrelevant clinical trials and of atypically expensive industry-generated NMEs, the corrected cost of bringing a pill to market, using PhRMA’s own data, falls to $240 million—“not chump change, but not $800 million, either.”

What did other analysts find when they examined the Tufts study? The Global Alliance for TB Drug Development (TB Alliance), a Swiss-based network dedicated to providing needed drugs to the developing world, estimated the cost of a new drug at $150 million to $240 million—identical to the Goozner-corrected $240 million estimate above.

In December 2001, the Health Research Group of the Ralph Nader–founded Public Citizen made a calculation of drug-development costs that utilized a different methodology. It used PhRMA’s data, but added all the R&D costs expended by pharmaceutical companies over a similar period in the 1990s and divided it by the number of new drugs that won FDA approval and reached the market during that period. Public Citizen arrived at a figure of $110 million.26 After tax deductions, this fell to $71 million, although the average R&D costs for NMEs were higher: $150 million. Not only is Public Citizen’s $150 million figure within the TB Alliance’s $150-million-to-$240-million range, but, observed Goozner, “If the industry-funded academic economists at Tufts had factored out the half of industry research that is more properly categorized as corporate waste, their numbers would have been similar to that of the Global Alliance.” (See “Rx Markup,” below.)

Rx Markup: Cost to Bring a New Drug to Market

So the Public Citizen, Merrill Goozner, and TB Alliance accountings of R&D costs for new drugs brought to market between 1994 and 2000, based on PhRMA’s own data, range from $71 million to $150 million ($240 million for the atypical NMEs).

And the $800 million figure so widely touted by drug companies? “This is just a thinly disguised advertisement for the pharmaceutical industry to justify continued price-gouging,” Public Citizen’s Dr. Sidney M. Wolfe told the New York Times.27

The high drug price tags are not just a U.S. problem. In the poorest regions of developing countries such as India, where two-thirds of the populace earn less than $2 a day, people who need expensive cancer drugs such as Avastin and Erbitux simply die. In fact, most branded Western drugs are out of their reach. A poignant 2009 New York Times essay, by my friend and breast cancer survivor Katherine Russell Rich, documents how in poor Indian villages oncologists are all but nonexistent.

Rich accompanies a local doctor to visit a woman dying from ovarian cancer and is shocked when the doctor urges the indigent woman to take heart from Rich’s recovery, which came only after expensive cancer medications, diligent medical monitoring, and a hellish $250,000 bone-marrow transplant.

“Look at her [Katherine Rich]. She has had cancer, and she is not crying. She is happy and hale.” The woman’s eyes widened. I felt my jaw tighten. She pulled herself out of bed. “Thank you,” she whispered, bowing gratitude on shaky legs, beaming at our connection, at this solid proof of hope, and it was as if I’d been socked. All this time, I’d thought what I’d had was miraculous luck, but in this plain white room, the knowledge came, inescapable: miracles are limited by place.

“If you smile, you heal faster,” Dr. Aggrawal told the patient. Away from her room, he said simply, “If you get cancer here, you die.” And her? Too advanced, he said. He brightened. “If you make a patient smile, you make them healthy,” he chimed. So cruel, I thought, breathless with anger. Then I saw. That’s what he had: words.

Most inhabitants of developing countries have little or no access to the cheaper drugs that Americans take as a matter of course (such as painkillers, vaccines, and antibiotics), so they die of ailments that are routinely avoided or treated in the United States.

These deaths are directly related to patent protection, because were the patent holders willing to allow licensing of low-cost or generic versions of their protected medications, which they do only rarely, more people would live.

In the United States, generic medications can often cheaply substitute for those medicines with expired patents. Generic medications are cheaper bioequivalent drugs that act in the body in substantially the same way as the branded medication, with blood levels close to that produced by the branded medication.28 The FDA considers that they have the same safety, efficacy, and manner of use and administration. Because the patent has expired, competition is possible, which tends to dramatically lower the price of generics in the United States.

Generic drugs are not the answer for developing countries, however. There are fewer drug manufacturers competing for these markets, and generics are often sold by the same corporation that sells the brand-name medications. This means that when generics are available, they tend not to be as cheap in the developing world as they are in the United States.

India had long been a traditional source of cheap drugs because its industrial tradition is coupled with a patent system that until recently issued monopolies on the various processes of making medications but did not recognize patents on the drugs’ components. So Indian firms reverse-engineered expensive branded drugs, then manufactured and sold them cheaply to the nations of the developing world. But World Trade Organization–brokered agreements have forced India to respect the Western patents it once flouted, and it is now legally blocked from reproducing cheap versions of many medicines.

The patent-mediated pricing crisis in developing countries is far more extensive and dramatic than in industrialized Western nations and Japan—the countries that pharmaceutical companies call home. Medication-access crises in the developing world are fed by complex political and cultural factors, so its struggle for drug access usually is treated as peculiar to the developing world.

However, medications that are priced beyond the ability of the populace to pay can also be viewed on a spectrum that encompasses the developed as well as the developing world. The crisis in the Third World is the same as our own domestic crisis in drug affordability because it shares the same cause: the determination of pharmaceutical manufacturers to maximize profits from their patents, regardless of patients’ ability to pay.

In contrast to our nation’s policies, some developing nations have not shrunk from their versions of “march-in” solutions. “March-in” or “step-in” powers are those wielded by governments when they intervene to, in effect, overrule a patent. Governments sometimes sweep a patent aside, refusing to recognize the monopoly in order to guarantee their citizens’ access to a needed drug. They issue a “compulsory license” that allows a company other than the patent holder to market cheaper versions of the medication, as, for example, Brazil did when it marched in to give its poor citizens with HIV and AIDS free access to lifesaving antiretroviral and other drugs.

Despite our much higher annual income, Americans, like citizens of the developing world, are increasingly unable to afford our medications. A 2010 Harvard Medical School study, the largest such ever performed, found that one in five prescriptions are never filled, and “affordability” topped the list of reasons why as given by doctors.29 Little wonder: according to a report by the University of Minnesota’s Stephen Schondelmeyer, PharmD, PhD, drug prices rose 27.6 percent between 2005 and 2009.30

Because health insurance is tied to employment in the United States, the recent double-digit gains in unemployment have created a new army of the uninsured. Data show us that a recession leaves people out of the workforce for longer than usual, during which time residual health benefits expire. Some of the unemployed may extend their health insurance through the Consolidated Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act, or COBRA, but this program requires the newly unemployed to pay at least the entire cost (up to 102 percent) of the premium to their former employer. COBRA is expensive and is likely to be one of the first lingering perquisites of employment to be abandoned in favor of staples such as housing and food. Even for those who can afford to maintain the benefits, it is temporary, expiring after eighteen months. But the recent surge of U.S. unemployment is only the latest challenge: medication prices have been rising beyond the reach of Americans for a long time.

Even those who are still employed have lost the level of health benefits they enjoyed a decade ago. As Heather, whose story opened this chapter, discovered to her dismay, companies with their eyes on the bottom line are forcing employees to shoulder an increasing proportion of their health-care insurance and costs, including medication costs. In 1999, a worker’s contribution to health insurance premiums averaged $1,543; by 2000, it had more than doubled, to $3,515.31 (See “Average Annual Health Insurance Premiums,” below.) Health insurers shift the responsibility for expensive care through plans that require employees to pay a large portion of their premiums or higher deductibles or to fund their own care through “health accounts” that are easily emptied by serious illness. (See “Percentage of Covered Workers,” this page.)

Small businesses constitute 95 percent of U.S. firms and are the most likely to offer their employees very limited insurance or none at all. Those who have no health insurance are likely to be the working poor who can least afford to pay for their own maintenance medications for high blood pressure or diabetes. They are unable to shoulder the medication costs associated with catastrophic illnesses such as cancer or stroke. Yet some very small businesses cannot afford to offer health insurance, especially when a single employee’s catastrophic illness could bankrupt the company.

As Heather’s case illustrates, even those fortunate enough to retain a job with health benefits have no guarantee that they can procure expensive lifesaving medications when they need them.

In 2009, the public “town hall” meetings around President Obama’s health-care-reform proposals drew thousands of people who shared horror stories of being financially ruined by medical costs or of being dropped by their insurers on some pretext when they developed a medical need. Such stories have become a commonplace of television and newspaper reports.

PhRMA has addressed the anxiety over drug affordability on its website, which offers a pie graph illustrating that “retail medication costs” represent only 10 percent of all health-care costs, according to an industry-supported report. To determine the significance of this cost estimate, one must know how a “retail medication” is defined, because medication costs are not confined to private expenditures by patients at pharmacies: medications are obtained during hospitalization, in nursing homes, and from in-hospital pharmacies, so perhaps medication accounts for well more than the 10 percent of health-care costs cited here. The site doesn’t divulge their roles in the overall figure. What’s more, the graph fails to acknowledge that the percentage of health-care costs ascribed to medications is escalating rapidly. In 2000, the $121.8 billion spent on retail medications accounted for only 9.4 percent of total health-care expenditures, but the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services calculated that the annual increase of retail medication expenditures is now 15 percent.32

Frankly, though, the invocation of such percentages is simply misdirection, just as the magician’s flourish draws one’s eyes away from the meaningful action. The 10 percent figure means little because health care of all types is far too expensive in the United States, where our total health-care expenditure reaches $1.3 trillion: what percentage of this unimaginable sum goes to medications is beside the point. At $130 billion, it is immense, and it is beyond our ability to pay.

We might be tempted to think that we have already expended the funds for these health-care costs, so that we obviously can pay for them. But this perspective fails to take into account that funds spent on expensive medication means funds diverted from other essential health services. Moreover, we are no longer able to cover even critical medication costs: despite the massive expenditures we have made, many medication needs are going unmet, even those that are promised by designated government programs. To illustrate this, let’s take the example of the federally funded but state-administered AIDS Drug Assistance Program (ADAP), which was established to provide expensive antiretroviral drugs to HIV-positive Americans who need them to live but cannot afford them.

Without reliable access to the medications, which cost an average of $12,000 a year, people with HIV are more likely to develop full-blown AIDS, to transmit the virus to their children or sexual partners, to require much more expensive hospitalizations and treatment, and to die. But ADAP funds are now depleted with regularity, and we have had to resort to rationing care.

Some states have had to open ADAP waiting lists, for example, to limit the drugs that are provided, or even to close the ADAP program to new enrollees.33 In September 2009, there were 157 people on the waiting list for ADAP; by September 2010, the waiting lists had ballooned to 3,337 people who were without the HIV medications they needed and could not get them from ADAP.34

For underinsured, HIV-infected people, the high prices of antiretroviral medications and the ADAP waiting lists have created a national crazy quilt of risk, with most HIV-infected people in some states getting the medications they need, while those in other states are more likely to die without treatment—or to require very expensive hospital intervention to treat opportunistic infections that could have been more economically—and humanely—prevented by ADAP meds. The expenditures we make in overpriced medicines mean that we cannot cover other, perhaps more important and efficient ways of protecting health.

In the end, what matters is not the percentage of health-care costs that medications represent but the percentage of Americans who cannot afford their out-of-control medication prices. This is not just a problem for the elderly, because according to Washington, D.C.’s nonpartisan Center for Studying Health System Change, 13.9 percent of people under age sixty-five could not afford their prescriptions in 2009—up from 10.3 percent in 2003. This means that costs forced about thirty-six million employment-age adults and their children to go without prescription drugs in 2009, nearly twelve million more than in 2003.35

The inability to afford medications challenges the middle class and the poor, the employed and the unemployed, and young and older Americans alike. But older people are especially vulnerable. When Medicare was enacted in 1966, well before passage of the Bayh-Dole Act, medications were inexpensive because private companies could not patent the fruits of government-sponsored university medical research and so could not enforce the monopolies that enable stratospheric drug pricing. And in those halcyon times, we have seen that some researchers chose not to patent their drug discoveries. No Medicare provision to cover the cheap prescription medications was thought necessary.

Today the medications for the chronic ailments that plague older Americans are quite expensive. The aging are caught between the Scylla of fixed income and the Charybdis of rising health issues that multiply with aging—such as diabetes, osteoporosis, cancers, and prostate disease. Forty-two percent of the elderly take four or more drugs.36

Their ability to stave off catastrophic ailments such as heart disease and stroke depends upon their affording prescriptions of hypertension pills, blood glucose, beta-blockers, and other preventative medications. They are not alone: recent studies suggest that the financial need to forgo necessary medications afflicts as many as half of all Americans. About half (49 percent) of the respondents to a July 2009 Kaiser Health Foundation survey cited cost as the reason they had taken risky steps such as skipping pills or letting prescriptions go unfilled.

One of every three said that the inability to afford medications had forced them to “rely on home remedies or over-the-counter drugs instead of seeing a doctor,” and one of every five said that cost had kept them from filling a prescription for a medicine. In addition, one of every seven Americans reported skipping a dose of medicine or cutting pills in half to make their medications last longer.37 No reports tell us how many, out of pride, do not admit to their doctors or to pollsters that they cannot afford to fill their prescriptions and so leave clinics as unprotected against catastrophic illness as when they arrived. (See “Half Put Off Care Due to Cost,” this page.)

It’s not surprising, then, that 94 percent of Americans in a 2009 Harvard/Kaiser Family Foundation poll think that drug costs are unreasonable.38 However, pharmaceutical corporations do not rely upon the court of public opinion to secure their pricing structures against political assault. Instead, the industry takes its case directly to lawmakers, deploying 1,544 lobbyists. In 2009, pharmaceuticals and health product lobbying totaled $263,377,975,39 and PhRMA’s share alone was $26,150,520.40 Through the lobbyists, pharmaceutical companies defend the high cost of prescription drugs as essential to recoup and subsidize research expenses and obtain special protections against unwanted controls and price constraints. Even more troubling, fully half of these health-care lobbyists are former government officials, cutting deals with their erstwhile colleagues for the industry’s benefits and special protections.

To this end, the drug industry’s lobbyists fight against the expansion of generic drug use and against proposals to allow the importation of cheaper drugs from Canada, both of which would help break its monopoly on some expensive drugs. Corporations also lobbied against lawmakers’ attempt to ease the plight of the elderly by adding a prescription drug benefit to Medicare.41 This is a battle that PhRMA would seem to have lost when health-care reform supplemented Medicare with just such a prescription benefit, yet in a surprising turnabout, the industry was a powerful and vocal champion of the Obama administration’s health-care reform.

On March 23, 2010, President Obama signed the historic Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act into law. The Obama administration’s brand of health-care reform is a brilliant piece of legislation that demolished several tenacious barriers to health-care access. It also recognizes governmental responsibility by providing access to the health-care system outside the private sector, by uncoupling health insurance from employment, and by providing mandatory coverage for the forty million Americans who currently lack it.

Health-care reform, most key tenets of which take effect in 2014, recognizes Americans’ personal responsibility as well, levying fines on people who neglect to obtain health insurance, for example (although this requirement to obtain health insurance may not survive legal challenges that were brought in 2010).

Corporate responsibility is also necessary. One critical step in that direction was achieved in a provision of the bill that eliminates the “pre-existing condition” as a criterion to deny or delay insurance coverage. This move clearly favors the needs of patients over the desire of insurance companies to curtail their costs. The provision extends coverage to higher-risk patients with known diseases that are likely to result in greater health-care expenditures. The law also prohibits lifetime limits on insuring health care, provides for covering children on family plans until age twenty-six, not nineteen, and expands access for low-income patients by subsidizing an additional sixteen million people who are added to the government’s Medicaid health insurance program. Coverage of abortion, that perennial political football, is prohibited.

The bill was fought by health insurers and their lobbyists through America’s Health Insurance Plans, a national association that represents 1,300 health insurance companies that cover more than two hundred million Americans.

But the pharmaceutical industry, which had similarly fought the Clinton administration tooth and nail when it attempted sweeping reforms in the early 1990s, lavished $100 million in marketing, television advertising, and grassroots organizing to promote the Obama administration’s reforms. Why?

Perhaps because, while President Obama’s reforms are sweeping and laudable, they are not perfect, in that they fail to regulate pharmaceutical drugs, eschewing the price controls and tightened federal regulation that the industry feared most.42 Even though the federal government is the nation’s largest purchaser of medications, through Medicaid, that agency consistently fails to use its purchasing clout to negotiate a better price, or even to import cheaper medications from Canada. In fact, Congress passed bewildering legislation in 2007 that expressly forbids Medicaid, the government, private retailers, and even private citizens from buying cheaper supplies of U.S. drugs from foreign sources—a tactic called reimportation.43

For example, a U.S. pharmacy may not purchase Canadian Prozac even though the drug costs 53 percent less there and is manufactured in the same plant. Law enforcement often looks the other way when private citizens buy small amounts of their drugs abroad—often capped at ninety days’ worth. Yet the rejection of price controls means a windfall for U.S. drug makers.

And it means a lost opportunity for the rest of us, because the Congressional Budget Office estimates that price controls that were proposed in 2003 would have saved the government $19 billion over the following decade, and private citizens would have saved $80 billion more. It is easy to see how; we’ve already seen why Canadian drugs are much cheaper than our versions, but the trend is global: for example, the same dosage of Nexium, a common heartburn remedy, costs $36 in Spain but $424 in the United States.44

Meanwhile, as noted above, the federal government provides subsidies and research-and-development funds to university researchers that allow pharmaceutical firms to produce these very drugs much more cheaply than they otherwise could. Finally, the expansion of medical insurance and access to care for tens of millions of Americans translates into tens of billions of dollars in earnings to drug makers as more people flock to doctors’ offices and leave with prescriptions for the industry’s products. According to a Huffington Post estimate, industry insiders expect health-care reform to boost new pharmaceutical-industry profits by more than $137 billion.45

All this makes the pharmaceutical makers, not the American people, the biggest beneficiary of health-care reform, which explains the industry’s heavy spending on reform’s behalf. Companies such as Johnson & Johnson, Pfizer, and Merck enjoy profits that averaged between $2 billion and $10 billion in 2008, making pharmaceuticals, as we’ve seen, the nation’s third-most-profitable industry, while the health insurance industry ranks a distant twenty-eighth. Yet the latter is heavily controlled by reform, and the former’s pricing and other business practices remain largely unregulated.

What do we, the medical consumers, receive for inflated drug prices, untouched by health-care reform? PhRMA’s website trumpets the value we are getting for our money, pointing to our longer life expectancy and reminding us that it has leaped more than thirty years since 1900, when the average U.S. life span was forty-seven years. (U.S. life expectancy dipped slightly in 2010, however.) And indeed, within the past century the drug industry has produced medicines that have transformed our lives by taming killers. Diabetes and childhood leukemia have been transfigured from death sentences into survivable illnesses. Better treatments for heart disease have contributed seven years to the average U.S. life span, and cancer treatments have extended it by 2.4 months, according to Roberto Ferrari, president of the European Society of Cardiology.46

Medications have freed sufferers of serious mental ailments from institutionalization, allowing them to become happy, stable, and productive members of society. Antirejection medications have permitted the development of surgical transplantation that allows patients to survive with new hearts, livers, and kidneys. The list goes on.

PhRMA reminds us that without pharmaceutical companies’ ingenuity and long years of arduous and expensive research, development, and testing, we would still be at the mercy of infectious killers such as tuberculosis, syphilis, and smallpox.47 This is true. Much of the medical innovation it refers to, however, is quite old and predates the post-1980 commercialization of research. More recent innovation has not addressed the major life span challenges such as producing an HIV vaccine, addressing the problem of drug-resistant antibiotics, or giving us medications that address the consistent health challenges faced by most of the world.

PhRMA does not, for example, discuss the fact that a baby girl born today in Japan, an industrialized nation that is home to 20 percent of the world’s fifty largest pharmaceutical companies, can expect eighty-five years of life, but a girl born the same day in Sierra Leone, where the average annual income is $139 and medications are hard to come by, can expect only thirty-six years. Fully ninety cents of every dollar expended on medical research is lavished on conditions that cause only 10 percent of “the global burden of disease.”48

The industry’s stirring commercials feature earnest young researchers who recount how the ailments of family members or cherished patients sent them on a personal mission to save others from a medical killer. Soaring anthems trumpet the company’s humanitarian mission of ameliorating human health at home and abroad.

Yet pharmaceutical companies seem driven by motives that they decline to trumpet, for the drug industry does far more than recoup its costs: its annual sales of $400–600 billion speak for themselves, eloquently announcing that pharmaceutical makers are living large. The industry’s profits, nearly 10 percent of its gross income, exceeded $65.2 billion in 2008 alone.49

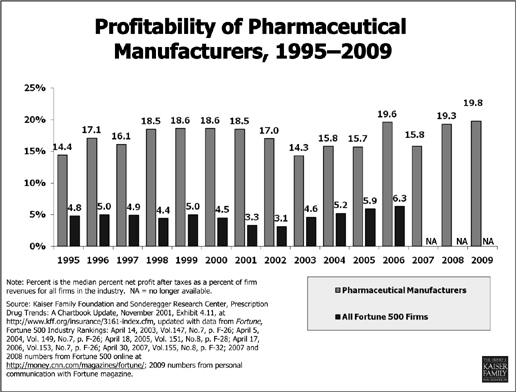

For approximately twenty years pharmaceutical companies enjoyed the highest profits of any U.S. industry. In 2002 the combined profits for the ten drug companies in the Fortune 500 ($35.9 billion) exceeded the profits of the other 490 businesses put together ($33.7 billion).50 (See “Profitability of Pharmaceutical Manufacturers,” below.)

If the R&D costs are so high, and if, as the PhRMA site claims, five to ten thousand candidate drugs are investigated for every one that ultimately finds its way to the medicine cabinet, how can an industry burdened with such astronomical costs see any profit, to say nothing of having become the most profitable industry on the planet?

It’s simple. Drug companies don’t pay for most of their R&D—you do. University research is typically subsidized by your tax dollars. Whether the university researcher partners with the corporation, whether she starts a biotechnology company that the corporation buys, or whether the corporation enters into a contract directly with a department of the university, the result is the same. The corporations market, sell, and profit from a patent that is the product of largely taxpayer-funded university research.

Generics are often hailed as the key to taming high medication prices. After the patent expires for a medication’s active ingredient, it can no longer sell licenses or extract royalties, and other companies are free to manufacture it without engaging in the extensive testing that the FDA requires for the approval of new drugs. The FDA instead requires only an Abbreviated New Drug Application, or ANDA, for generic versions that are simple, rapid, and far less expensive. A generics manufacturer can begin this truncated approval and testing process before the patent actually expires without legally infringing on the patent, so that it can begin selling the cheaper generic version the day after the brand-name patent expires.

This makes generic medications much cheaper to produce, and these savings are usually passed on to customers, especially in the United States. The availability of generic versions of branded drugs has sometimes eased patients’ difficulty in paying for them.

Pharmaceutical makers have historically opposed generic medications because of the competition from these low-priced drugs. But more recently, they’ve pursued other strategies to reduce the competition from generic versions. The rivalry between generics and brand-name manufacturers has been marked by conspiracies that violate antitrust laws.

For example, the Drug Price Competition and Patent Term Restoration Act of 1984, popularly known as the Hatch-Waxman Act, grants 180 days of market monopoly to the generic manufacturer that is first to file an ANDA for a generic version of a brand-name drug.51 However, in 2006 the Department of Justice charged Bristol-Myers Squibb and generics maker Apotex with conspiring to violate the Hatch-Waxman Act by agreeing that Apotex would delay bringing clopidogrel, the generic version of the blood thinner Plavix,52 to market. This left the field free for BMS and its high prices, effectively extending BMS’s monopoly on the drug beyond the legal limit.53 In return, BMS agreed to share the resulting profits with Apotex. Both companies stood to increase their earnings, but Americans continued to pay inflated prices.

The Department of Justice filed criminal charges against BMS and one of its officers, Dr. Andrew G. Bodner. Both BMS and Bodner admitted lying and pled guilty, resulting in a $1 million fine for the firm and two years’ probation for Bodner. There are many other similar cases where pharmaceutical companies have been accused of skirting the law to continue profiting from patents. These include the 2009 complaint that Solvay paid generic drug makers Watson and Par to delay generic competition to Solvay’s best-selling branded testosterone-replacement drug, AndroGel, whose 2007 sales topped $400 million.54 In 2004, Warner Chilcott agreed to pay Barr $20 million if Barr delayed entering its generic version of the very profitable Ovcon 35 oral contraceptive for five years, and a 2001 complaint alleged that Hoechst Marion Roussel Inc. paid generics maker Andrx millions of dollars to delay bringing to market a competitive generic alternative to the hypertension and angina drug Cardizem CD.55 Such cases resulted in fines, probation, or consent agreements in which drug makers admitted to wrongdoing.

Moreover, a 2010 Federal Trade Commission report, “Overview of FTC Antitrust Actions in Pharmaceutical Services and Products,” describes 104 such legal actions it has undertaken,56 mostly between patent holders and generics companies that were trying to maintain monopolies on drugs whose patents had legally expired or that had otherwise conspired to evade or to delay lowered generic pricing.57

Are such “pay for delay” arrangements between pharmaceutical houses to delay generic manufacturing legal? As recently as 2010, one analysis stated that “The Circuit Courts are split. While the Sixth Circuit agrees with the FTC that reverse payment settlements are per se violations of the antitrust laws, … the more recent wave of decisions in the Second, Eleventh and Federal Circuit Courts of Appeals have held reverse payments to be acceptable restrictions within the exclusionary scope of patents.”58

Drug makers often complain of a limited time to exploit their patents, but they do have remedies, because they use a variety of legal strategies to extend the period during which they can capitalize on their monopolies. Drug firms call these strategies for maximizing their monopolies “life-cycle management” or “evergreening,” on which they expend a great deal of creativity and lobbying to stave off laws that might enforce or tighten patent expiration.

Patents usually grant twenty years of exclusivity but typical patent extensions of five to fourteen years are granted to cover the periods of FDA-mandated testing59 and certain other conditions.60

Patent life management strategies include patenting polymorphs, which are simply new physical forms of the medication—in powders, pills, extended-release, capsule, gel, topical tablet, or liquid versions, or using different solvents. These may involve minor changes in dosage strength, but they needn’t do so to buy the company varying amounts of extra time to exploit its monopoly.

Chemical tweaking of drug compounds pays off in new patentable drugs as well. For example, some active ingredients exist in “left-handed” and “right-handed” forms—chemically different structures that are mirror images of each other. These are called enantiomers, which the USPTO recognizes as separate inventions. Although enantiomers may have different biological effects, they can be similar enough for one to be patented for the same use after the patent on the other has run out.

Moreover, creative industry chemists are not limited to patenting the right- or left-handed versions of these drugs. An equal mixture of the two forms, called a racemic mixture, can be patented in addition to the right- and left-handed enantiomers.61

The antidepressant drugs Lexapro and Celexa, for example, are differently “handed” versions of the same molecule. Lexapro contains only the left-handed version (S-citalopram), and Celexa is a racemic mixture of equal parts of the left- and right-handed versions (S-citalopram and R-citalopram). Yet each was awarded its own patent. If only one version of the drug is active, then separating it into a drug with the racemic mixture and another drug consisting only of the active enantiomer, as the maker of Lexapro and Celexa did, imparts no clinical benefit to the patient and may dilute its action, but it benefits the company by providing it with another twenty-year patent for the same medication.62

In order to win a new patent, the drug company need only show the USPTO that its proposed “new” drug is marginally better than the old one. This is easier than it sounds, because scrutinizing the various components of a clinical trial will often reveal some subgroup or application where a medicine pulls slightly ahead of its very similar competitor.

Take the popular heartburn medication Prilosec, which is a racemic mixture of two enantiomers. This blockbuster drug earned AstraZeneca $26 billion and was cryptically popularized in early direct-to-consumer advertisements as the “purple pill.” As Prilosec’s 2001 patent expiration date loomed, AstraZeneca tested a single enantiomer of Prilosec, which it dubbed Nexium, and found that its activity was similar to Prilosec’s. Testing Prilosec against its alter ego showed that for one uncommon condition, erosive esophagitis (a condition in which areas of the esophageal lining are inflamed and ulcerated, often by chronic acid reflux), Nexium worked slightly better. Nexium was awarded a patent to become the second-generation “purple pill,” sold at a similarly high price to unwitting patients who did not realize that the nearly identical Prilosec was now off-patent and available as a cheap OTC pill at the same pharmacies where they filled their pricey Nexium prescriptions.

The only demonstrated differences between the two were a barely perceptible difference in effectiveness for an uncommon complication of gastric reflux—and an enforceable patent.63 The Wall Street Journal observed: “The Prilosec pattern, repeated across the pharmaceutical industry, goes a long way to explain why the nation’s prescription drug bill is rising an estimated 17 percent a year even as general inflation is quiescent.”64

The selling of copycat or “me too” drugs did not begin with modern drug design. In The $800 Million Pill, Goozner writes of how they were already common in 1960 when Senator Estes Kefauver of Tennessee held hearings to probe the extent of copycat drugs.

Kefauver pressed the former head of research at E.J. Squibb to estimate how much corporate drug research was driven by the desire to come up with me-too drugs. The retired executive replied that “more than half is in that category. And I should point out that with many of these products it is clear while they are on the drawing board that they promise no utility. They promise sales.”65

Today, these patented products of questionable utility—doppelgänger medicines in various physical forms and tweaked chemical structures—require very little in the way of development and minimal testing, yet they are not sold at low prices. Other me-toos include combining two medications into a dual pill such as Pfizer’s Caduet, which is a patented combination of Norvasc (amlodipine besylate) and Lipitor (atorvastatin calcium), a “statin” drug used to protect the heart by reducing low-density lipoprotein or “bad” cholesterol while raising high-density lipoprotein or “good” cholesterol levels. Similarly, BiDil is a patented combination of isosorbide dinitrite and hydralazine, two generic medications for the treatment of congestive heart failure. “Repurposing” a drug for new uses is a practice so widespread that 84 percent of the fifty top-selling pharmaceuticals in 2004 were approved for additional indications after their first licensing.66 And, under the pediatric exclusivity section of the Food and Drug Administration’s Modernization Act of 1997, testing a medicine for use in children adds six months to its patent’s life, allowing it to be sold to both children and adults under extended patent protection. Claritin’s six-month extension in patent life meant an additional $1 billion in earnings for Schering-Plough. Both FDA medical evaluators and patent officers complain they are under pressure to approve such measures and patents based on them.67

The “patent cluster” is another useful patent-extension tactic. A company keen to hold on to a blockbuster drug’s expiring patent may file dozens or even hundreds of closely related new patent applications, often of dubious merit, to confuse and intimidate potential generics firms and to maintain its monopoly. Drug firms have taken out as many as 1,300 patents across the European Union for a single drug.68 Pharmaceutical companies have recently begun teaming up with generics manufacturers to make out-of-court settlements that delay the market entry of cheap generic versions of expensive branded drugs.

So we return to the key question: If research and development costs are more often borne by the government than by large drug firms and if these companies deftly employ various stratagems to ward off patent expiration—and do all this so well that their profits consistently place them at the global corporate apex—why do medications cost so much?

The prices are high because the structure of the U.S. patent system leaves us no choice but to meet their demands.

It is no accident that the highest drug prices are for the most serious illnesses. The highest drug prices reflect not R&D costs, but rather what desperately sick patients are willing and able to pay to stay alive. Erbitux costs less in Canada than in the United States simply because Canadians struck a hard bargain when they contracted to pay less than the $208,000 U.S. price tag for John Colacci’s treatment. Consider also the cost of treatment with the breast cancer drug Herceptin (trastuzumab), which is $35,000 a year. Herceptin was produced by twenty years of research at several universities and was largely financed, as is usual, by federal funds. When it was ready for market, Genentech obtained a patent via the Bayh-Dole Act. Yet Genentech justified its price by explaining that it had cost $150–200 million to develop the drug—costs that were, of course, largely borne by taxpayer-subsidized university research, not by Genentech. Roche, which acquired Genentech,69 now generates $2 billion a year from Herceptin sales although it did not invest in its R&D costs: this $2 billion, then, reflects not Herceptin’s R&D costs but what cancer patients are able to pay to stay alive.

The United States does not pressure drug companies to lower their prices, and individual patients like Heather and John Colacci lack the clout to negotiate them, but one private U.S. industry does wield enough power to force the negotiation of lower medication prices—pharmacy benefit managers, or PBMs.70

PBMs such as CVS Caremark and MedCo Health Solutions manage the medication-benefits portion of health insurance for 210 million Americans. They are hired by most health insurers for corporations and for the government, including large insurance plans such as Medicare. PBMs also procure drug prices for other organizations that provide health insurance to their members. The leverage provided by their vast base of insurees enables the PBMs to force drug makers to accept lower prices. Mark Merritt of the Pharmaceutical Care Management Association, the major PBM group, told the Wall Street Journal that “one of the great services PBMs provide is to play drug companies off one another and get big discounts on drugs.”71

PBMs often are expected to retain part of the difference between the regular price and the negotiated price of the drugs as compensation, but because PBM–drug company negotiations are conducted in closed-door meetings, their clients cannot know the size of the difference between the price the PBM wrangles from the pharmaceutical firm and the price it extracts from the insured. Therefore, secrecy surrounds the savings the PBM retains and how much is passed on to employers and consumers. (See “Pharmacy Benefit Managers,” below.)

Pharmacy Benefit Managers (PBMs) Control the

U.S. Prescription Drug Market

Critics such as former New York congressman Anthony Weiner called for greater transparency. Weiner protested that the secrecy hides the fact that too little of the savings reaped by PBMs are passed on to the employers and the insured. But Merritt disagrees: “The thing that drives prices down is competition, not this kind of transparency which tends to help suppliers keep prices higher.” Representative Weiner drafted provisions for an early version of the 2010 health-care reform bill that would require accounting to “cut down on inside deals that benefit only the PBMs and the drug companies,”72 but the provision did not appear in the final bill.

Employers and insurers seem to be increasingly distancing themselves from PBMs. McDonald’s and IBM are among the sixty major U.S. employers that spend more than $4.9 billion on medications annually, and they are calling on PBMs for greater transparency.

Consider, too, the corporations’ claims that they focus on producing the lifesaving medications that prolong our lives and promote our health. To bolster this claim, they point to such triumphs as the polio vaccine and new antibiotics and take credit for the U.S. life span’s growing nearly thirty years within a century as well as for the control of many once-fatal diseases.

At PhRMA’s 2009 annual meeting in San Antonio, its then-CEO Billy Tauzin (a former congressman who was key in getting the pharma-friendly Medicare Prescription Drug Bill passed), declared: “You have called for a war against cancer to find the cures that, in our lifetimes, will put an end to cancer, just as we once managed to put polio behind us.” Without the industry’s willingness to invest heavily and to take huge risks, drug makers claim, our children would still be crippled or dying en masse from diseases like polio.73 However, the polio vaccine was never patented and was subsidized by the March of Dimes, not private industry, so it doesn’t make the best argument for PhRMA’s monopolistic drug-research framework.

More important, penicillin, which was found to tame syphilis, and antibiotics against tuberculosis were developed in the 1940s. Drug makers no longer focus primarily on medications that target current health crises; those days seem far behind us.

And although TB has enjoyed a disturbing renaissance due to burgeoning antibiotic resistance, drug makers have given us precious little to fight it. As the existing antibiotics lose their effectiveness because of disease resistance, nothing has emerged to take their place. Similarly, cures for childhood leukemia are important success stories, but they are old ones. When it comes to the contemporary mass killers and cripplers of Americans, the industry has offered us too little against AIDS, hepatitis C, and other contemporary scourges.