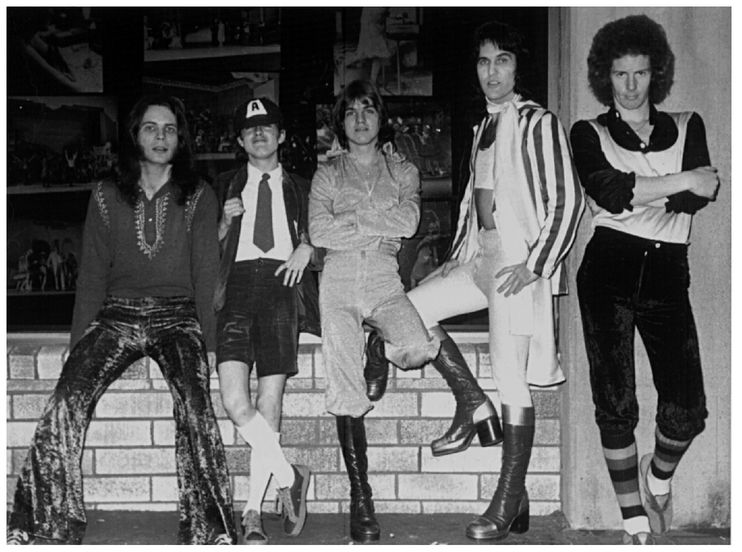

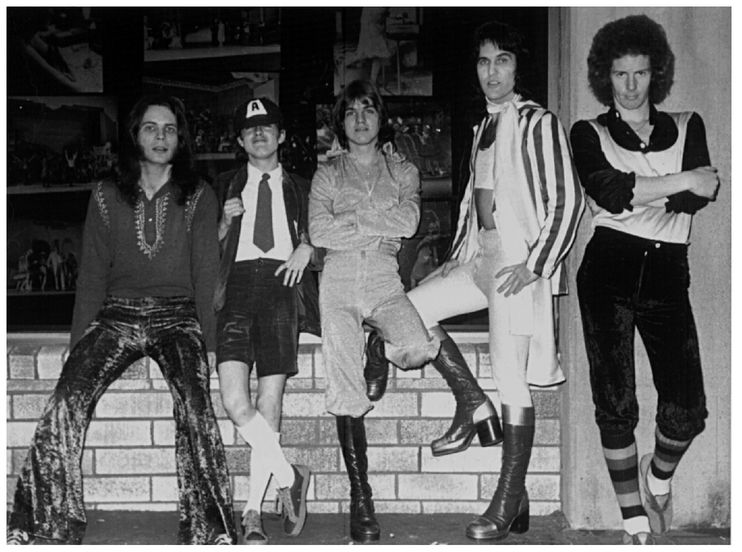

AC/DC’s first photo session, July 7, 1974, outside Her Majesty’s Theatre in Sydney. Left to right: Rob Bailey, Angus Young, Malcolm Young, Dave Evans, Peter Clack. (Philip Morris)

8. THE YOUNGS

Where the water sparkles on the harbor, in the wash of the Bridge and the Opera House, Sydney is one of the postcard prettiest cities in the world. But the daily reality for most Sydneysiders is a massive suburban sprawl. Crawling along Parramatta Road in a gritty carbon-monoxide haze, you are confronted by the bleak brick-veneer vista that is Sydney’s dreaded western suburbs.

The west is commonly decried as a cultural wasteland. But that’s the exclusive opinion of the snobbish arbiters of taste who believe that art doesn’t exist outside institutions, and don’t understand art that does. The first artistic language of suburbia is rock’n’roll, and Sydney’s western suburbs have a long and impressive rock’n’roll tradition.

When William and Margaret Young and their six children emigrated to Australia from Glasgow, Scotland in 1963, it was here in the western suburbs that they landed and settled. George was 15 (born November 6, 1947); Malcolm was ten (January 6, 1953); Angus eight (March 31, 1955). The rock’n’roll scene was already thriving.

“Me dad couldn’t get work up in Scotland,” Angus later told Sounds, “he found it impossible to support a family of our size, so he decided to try his luck downunder.”

Like others straight off the boat, the Youngs were ushered into a hostel—at Villawood—where they would stay until they found suitable accommodation for themselves. “It was like a prison camp,” Malcolm later told Spunky, “all these old tin shacks.”

The Young family was fairly musical in an amateurish sort of way, as George once put it. It was the boys’ older sister, Margaret, who was largely responsible for turning the boys onto rock’n’roll; in fact, she was the one who gave AC/DC their name and put Angus in the school uniform. After the Second World War British seaports like Liverpool and Glasgow were on a direct shipping route to the United States. As rock’n’roll lore has it, Mersey-beat itself was inspired by the American music—R&B, blues and hillbilly records—which came ashore there. In Glasgow, Margaret was listening to Chuck Berry, Little Richard and Fats Domino even before they were stars.

Alex, the oldest Young boy, went into music professionally as a saxophonist in Emile Ford’s Checkmates. He left home before the family emigrated, to join the Big Six, whose claim to fame was that they backed Tony Sheridan after the Beatles walked out on him. The Beatles connection was strengthened when Alex went on to join Grapefruit, a lesser light on the Beatles’ own Apple label.

George Young was a promising schoolboy soccer player—an interest common among Scots, and one certainly shared by brother Malcolm—but he was keener still on music. Although the Youngs spent barely three weeks at Villawood before they moved into a place of their own down the road in Burwood, George managed in that time to hook up with the best part of a band. His cohorts numbered an Englishman and two Dutchmen: frontman Stevie Wright, who was lured away from surfsters Chris Langdon and the Langdells; guitarist Harry Vanda, formerly of Holland’s premier instrumental combo the Starfighters; and bassist Dick Diamond.

Burwood, with its wide boulevards and solid, free-standing red-brick Federation homes, might almost have seemed posh to working-class Scots. Indeed, today it is becoming gentrified. But in the sixties, it was a rough and ready neighborhood of “new Australians,” which would play host to violent meetings of rival gangs down at the station on Saturday nights. If the rough streets of Glasgow weren’t indoctrination enough for the Young boys, this was a fine finishing school.

Burwood also boasted a thriving garage band scene. “Every new English kid that arrived brought all the latest things with him,” remembers native Peter Noble, who played with Brits in a band called Clapham Junction.

George’s nascent band found a drummer, Englishman Snowy Fleet, then resident at the East Hills Migrant Hostel. Fleet was a Liverpudlian and at 24 was much older and more experienced than his new bandmates. He had come out to Australia with his wife and child after walking away from a choice gig with the Mojos, who would go on to join Beatles manager Brian Epstein’s stable and produce the classic 1964 hit “Everything’s Alright.” Snowy would name the band the Easybeats and initially manage it, too.

The Easybeats are generally acknowledged as the first truly original Australian rock’n’roll band, but the irony is that its individual members were hardly Australian at all. Still, the band was immediately and passionately embraced in Australia as “our own.” Their first proper gig was in late 1964 at an inner-Sydney joint called Beatle Village. From there, they leapt and bounded to the top of the charts.

The Easybeats looked good and sounded good. They dressed sharp, which gave them greater sex appeal than their closest Australian rivals, most of whom looked like civil servants. What’s more, they could both play and write rock’n’roll. And Little Stevie was a livewire showman.

After signing a management deal with erstwhile north shore realtor Mike Vaughan, the band was introduced to Ted Albert, a friend of the highflying Vaughan who was in music publishing. Albert, a budding producer with an ear for the future in beat music, was the middle of three sons of Sir Alexis Albert, whose father Jacques Albert had founded J Albert & Son, the oldest independent music publishing house in Australia. With interests in radio and film, too, Alberts was estimated in the 1990s to have a total worth of more than $45 million.

Jacques Albert had migrated to Australia from Switzerland in 1884 and set up shop as a music publisher. Immediate success with a single product called The Boomerang Songbook laid the foundations of the family fortune. Turnover was maintained as Alberts picked up Australian rights to an impressive array of song catalogues.

Ted Albert was 26 when Beatlemania hit in 1963, and he got caught up in it. He wanted a Beatles of his own. Initially, he had headhunted the already successful Billy Thorpe and the Aztecs to work with his newly-formed Alberts Productions. But when Mike Vaughan invited him down to have a look at the new group he was representing, Ted, in his own words, almost broke his neck getting a contract drawn up. The Easybeats, after all, did what no other Australian band did—they wrote their own material. To a publisher this is obviously important.

Ted immediately took the band into the old 2UW Radio Theatre (the family owned the station) to cut demos. A debut single, “For My Woman,” was released in March 1965 through Parlophone, and while it wasn’t a hit, it was encouragement enough to Ted to get any sort of reaction to original material. Two months later the Easybeats’ second single, “She’s So Fine,” shot to number one, and dragged the forgotten first single into the top five as well. “Easyfever” took hold; only Normie Rowe could compete with the group for the title of premier Australian pop attraction.

The Easybeats went on to produce an incredible run of hits, and cut three albums before they left Australia in July 1966 for London, then the Mecca of the pop world.

With the rise of the Easybeats, Alberts Productions also established itself as a force in the fledgling Australian music industry. George Young would later praise the urbane Ted Albert as a man who, self-taught in the art of recording rock’n’roll, “knew as much about feel and balls in a track as anyone I’ve ever met . . . and had a very good ear for picking the right songs.”

Ted applied his instincts to running Alberts, and was rewarded with a string of hits for Billy Thorpe and the Aztecs as well as the Easybeats. Dirtier, uglier R&B merchants like the Throb and the Missing Links fared less well commercially, but left a lasting impact.

When Ted followed the Easybeats overseas, Alberts wound down operations in Australia, at least temporarily. On the international scene, the Easybeats scored immediately, and massively, with the mod anthem “Friday On My Mind”—then spent the next three years falling apart in the search for a follow-up.

Manager Mike Vaughan was out of his depth overseas. It reached a point, in 1967, where the band was signed “exclusively” to several record companies around the world, which left them hamstrung. All this experience gave George the bitter wisdom he would later apply to AC/DC’s career.

Artistically too, as George would later regret, the Easybeats strayed off the track, or were led astray. The band progressed through two very distinct cycles, in Australia and then overseas, both of which began and ended with rock’n’roll, but in between went very wayward. Initially, in Australia, flushed with their first success, the band indulged itself and tried to be clever. Whilst the resulting songs like “Wedding Ring” and “Sad and Lonely and Blue” were still hits, albeit minor ones, George at least claims to have derived much greater satisfaction out of the band’s subsequent return to rock’n’roll with songs like “Women” and “Sorry.”

By the time “Sorry” reached number one in Australia in November 1966, the Easybeats were ensconced in the studio in London with Who/ Kinks producer Shel Talmy, cutting “Friday on My Mind.” “Friday on My Mind” followed “Sorry” into the number one position in Australia a mere month later, and eventually, after a few false starts, made top ten in Britain and top 20 in America, not to mention hitting very big all across Europe, especially in Germany.

But “Friday on My Mind” would prove to be both a blessing and a curse, as big hits sometimes are for bands. Despite the layers of businessmen who siphoned off much of the Easybeats’ earnings, it was certainly a meal ticket for Harry Vanda and George Young, at least, since they had written the song. It also made George aware of the value of the often overlooked European market.

Contrary to all the evidence which suggests it seldom works, record companies inevitably want a band to produce a clone follow-up to consolidate the success of a first hit. To an artist, this sort of pressure is like a red rag to a bull. George and Harry, who by now had taken complete creative control of the Easybeats, would do anything but repeat themselves, or anything close. So the band’s singles that followed “Friday on My Mind” were all over the shop, a grab bag of psychedelic dabblings which only sporadically attained the vitality of their earlier work. It wasn’t until late 1968 with “Good Times,” a raging slab of rock’n’roll (successfully revived in Australia in 1988 by INXS and Jimmy Barnes), that George and Harry perhaps realized they’d been cutting off their nose to spite their face.

The lesson in all of this for George, which he would pass on in no uncertain terms to his eager little brothers, was that you must stay true to your roots.

“Good Times” came too late. By then, the public didn’t know who or what the Easybeats were, and the band themselves no longer shared the sense of unity they had when they all lived out of each other’s pockets. George and Harry had become estranged from the rest of the band, spending all their time together in the studio and refusing to tour at any length. Eventually they moved into their own four-track studio-flat in London.

The band was on its last legs—broke, and with drugs beginning to eat away at it. Stevie Wright began the downward spiral that would lead to the heroin addiction which would blight his life for many years.

The last album that bore the Easybeats’ name, Friends, was barely that. A ragtag collection of demos recorded by Harry and George, with only Stevie otherwise appearing on a few of the tracks, it did, however, yield the Easybeats’ last minor hit, the good-rocking “St Louis.”

On the strength of that, the band managed to get it together sufficiently to tour Australia in the spring of 1969, when they were supported by the Valentines. It would be their last hurrah. At tour’s end, Harry and George headed straight back to their London studio lair. Word was that the band had finally broken up.

Back in London, Harry and George picked up where they had left off. The next three years were like one long lost weekend as they worked at establishing themselves as an all-round production team, spotting talent, and writing and recording. They sold a few songs and produced a record or two, but nothing world-beating. Little wonder then that Ted Albert—who kept up an ongoing game of chess with George by telephone—was able to lure them back to Australia in 1973.

Spurred by success with a young pop singer-songwriter, Englishman Ted Mulry, Alberts was reborn in the new decade as a record label in its own right. Mulry’s first single “Julie” was a minor hit. His second “Falling in Love Again,” penned by none other than Harry and George, and released for Christmas 1970, was a smash.

The signing that consolidated Alberts’ comeback was John Paul Young. Englishman Simon Napier-Bell, former manager of the Yardbirds, among other, more dubious, distinctions (he later managed Wham!) was then working at Alberts on a kind of exchange program. He was looking for a singer to match with another of Harry and George’s demos which was lying around, a song called “Pasadena.” Cut with John Paul Young, it hit just outside the top ten in April 1972.

At that point, Ted promised Harry and George the world, or at least that he would build them a studio, and that they could run it as they chose. Harry and George, in return, promised to get down to some serious work.

AC/DC has always been Malcolm Young’s band—and it still is. Malcolm formed the band in the first place, and even as Angus has gradually assumed the role of front man, Malcolm was always the driving force—the primary writer, and the one to whom the last word in the band belonged. And while Angus has come to share much of the songwriting load with Malcolm, the pair’s equal, if silent partner in the band has always been big brother George. Having already been around the block with the Easybeats, suffering shortcomings and rip-offs, George was embittered, and in many ways AC/DC would be his revenge. AC/DC would achieve what the Easybeats couldn’t—control of their own destiny, and sustained success.

George was much more than merely AC/DC’s coproducer—it was he who honed the band’s sound and songs into a coherent, commercially viable entity. But George’s brilliance was that he never tried to polish a turd. Where less incisive record producers would have tried to iron out AC/DC’s rough edges and tart up the sound, all George ever aimed to do was harness that power, give it shape and direction.

As George’s crowning achievement, AC/DC also marked the inauguration of a dynasty in Australian rock’n’roll, one whose influence is still pervasive. It is felt not just in the success of AC/DC, but also in the seminal influence AC/DC exert all over the world, and in the other work George and Harry have done as part of the Alberts Productions axis. In the mid-seventies, Alberts produced an unprecedented string of hits for artists like Stevie Wright (by then a solo artist), John Paul Young, and the Ted Mulry Gang. Perhaps more importantly still, George and Harry’s production work for such bands as Rose Tattoo and the Angels virtually defined the unique Australian rock genre which grew out of the thriving pub circuit.

George Young lived at home in Burwood—when he wasn’t on the road—right up until he went overseas in 1966. Growing up in his slipstream, it was almost inevitable that Malcolm and Angus would follow him into rock’n’roll. Angus would later recall: “One day George was a 16-year-old kid sitting on his bed playing guitar, the next day he was worshipped by the whole country. I was going to school at the time—or rather, trying not to go to school—and I was very impressed. He was getting all the girls.”

As Angus has testified, there was always a guitar around the Youngs’ house. Nevertheless, as Malcolm told Glenn A. Baker, “We didn’t get much encouragement. Dad was still asking George when he was going to get a proper job. The Easybeats weren’t making much money in England by the end and I don’t think the family liked the drug thing that was happening in rock by that time.” But music was an irresistible force, and the two brothers picked up as much by osmosis as they did from old records by Muddy Waters, Ike and Tina Turner, Little Richard, Chuck Berry, the Who, the Stones or the Yardbirds.

Both Malcolm and Angus attended nearby Ashfield Boys High, a school notorious for its toughness. Malcolm told Spunky, “Because we were little guys, everyone kept pushing us around, and we had to fight or get beat up.”

The boys’ father insisted they get a trade no matter what, so when Malcolm left school at 15 he started work as an apprentice fitter. At the time, Sydney’s inner west was buzzing with music. The powerful Nova agency, which had handled Fraternity, had its offices in Ashfield, and the specter of new local bands like Sherbet, Blackfeather and the Flying Circus loomed large. Malcolm jammed around in mates’ bedrooms and garages.

In 1971, when he was working as a sewing machine maintenance man for Berlei, who make the bras, Malcolm met a band presumptuously called the Velvet Underground, who had just moved to nearby Regents Park. They were looking for a guitarist, and Malcolm got the gig.

The Velvet Underground had formed in Newcastle, a steel town on the New South Wales coast, in 1967. With a repertoire based around material by the Doors and Jefferson Airplane, they became top dogs on the local dance circuit. When front man Steve Phillipson threw in the towel, the band relocated to Sydney. Finding the guitarist they sought in Malcolm—they knew he was the brother of George Young, although Malcolm didn’t play up the fact—they experimented with vocalists until they settled on Andy Imlah, who was poached off a nondescript local outfit called Elm Tree.

The band was picked up for representation by Dal Myles (now a newsreader on Sydney television), who constituted Nova’s sole rival. Thus the Velvet Underground became popular on Sydney’s suburban dance circuit, where they would often share the bill with another one of Myles’ clients, erstwhile Alberts solo artist Ted Mulry, who was then using the aforementioned Elm Tree as a backing band. Like the Valentines, Elm Tree had started life with two lead vocalists—a young sheet-metal worker by the name of John Paul Young sharing the spotlight with Andy Imlah—but the band was left in the lurch after Imlah went off to join the Velvet Underground.

Malcolm already knew Ted Mulry through George, who’d met him at the 1970 Tokyo Song Festival where Mulry’s “Falling in Love Again” was unveiled.

TED MULRY: “When I came back from Japan, it was around Christmas, and George was home for Christmas, and he said, What are you doing for Christmas? I said, I dunno, whatever; he said, Well, New Year’s Eve, we’re having a do at the folks’ place, come around. So I said, Alright. And you can imagine! You go along with your guitar, and they’re all musicians, and you have a few drinks . . . The funny thing was, I was the only non-Scot there, there wasn’t even any other Englishmen, and you couldn’t understand a word they were saying! But what a ball! We had a big singsong, and you’d get everything out, somebody had a squeeze-box, and there was a mouth organ, the bass would come out, guitars. It was great.”

With the Velvet Underground gigging busily, Malcolm threw in his job and became a professional musician like the rest of the band. He would never work a day job again.

The young Angus was allowed to go out and see his brother play—and he would sit wide-eyed at the front of stage—as long as he was brought straight home. But the Velvet Underground were pretty well-behaved anyway. They would go back to Burwood after gigs to drink Ovaltine.

“We used to go round to pick Malcolm up,” recalls Velvet Underground drummer Herm Kovac. “The first time, this little punk skinhead answered the door. It was Angus. I hid behind Les [the guitarist] ; in those days you’d hear about the skinheads down at Burwood Station, Strathfield Station. Shaved head he had, big boots. He said, Eh, come in ’ere. So we follow him into his room, he straps on his SG, jumps on the bed, and goes off on this exhibition, running over the dressing table, showing off, couldn’t play any chords, just lead, and when he finishes he says, Whaddya reckon? You had to say, Pretty good, Angus. Every time you’d go there you’d have to go through this same ritual.”

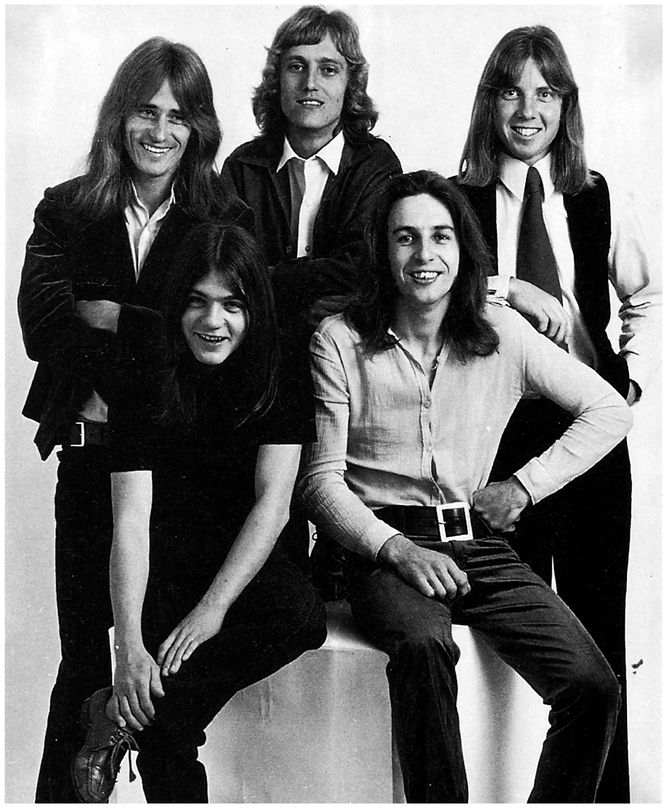

Malcolm Young’s first real band, the unapologetically named Velvet Underground, ca. 1972. L-R: Herm Kovac, Malcolm, Andy Imlah, Michael Szchefswick, and Les Hall. Both Kovac and Hall went on to play in the Ted Mulry Gang, AC/DC’s Alberts labelmates. (courtesy Herm Kovac)

The Velvet Underground were writing a few songs of their own, but their set was still mainly covers—the Stones’ “Can You Hear Me Knockin’?” and “Brown Sugar,” and T Rex songs.

HERM KOVAC: “Malcolm never had guitar heroes. You know, when you’re a teenager you have pin-ups on the wall. Malcolm and Angus never had any pictures on their bedroom wall. The one guitarist who was Malcolm’s hero, who he did have a picture of on the wall, was the guy you’d least expect—Marc Bolan. Malcolm made us do about six T Rex songs. I said, I hate ’em, they all sound the same. But Malcolm loved Marc Bolan. Mind you, the picture he had of him was tiny!”

Ted Mulry had been the first to cut a version of George and Harry’s “Pasadena,” but Simon Napier-Bell was convinced there was a hit in it yet, and so he asked the Velvet Underground to do it. They demurred. They were a rock band, they protested, and “Pasadena” was pop schlock, even if it was one of Malcolm’s brother’s songs. The Velvet Underground in turn suggested that maybe “Mungy” Young, Elm Tree’s other singer, would be well suited to the song. John Paul Young was thus launched on his own career.

With the dissolution of Elm Tree now complete, Ted Mulry, who was still producing hits as a solo artist, needed a new backing band, and so he became something of a double-act with the Velvet Underground. The Velvet Underground would open the show, and then play behind Ted for his set. But Malcolm was getting itchy fingers. He wanted to go off and get something of his own together. Late in 1972, then, the Velvet Underground folded. The rest of the band, plus Ted, transmuted into the Ted Mulry Gang.

HERM KOVAC: “When Malcolm left Velvet Underground, the reason he left was that Deep Purple had come out then, and he wanted to play all Deep Purple-type stuff. The rest of us weren’t really into that. So he went and tried it, couldn’t get any gigs, and then the early AC/DC played Beatles songs and all that, just to get work.”

At around the same time Malcolm was starting to get something of his own together, George and Harry finally arrived back in Australia for good. But though they went back to work for Ted Albert, they did so with a guardedness that would become part of their trademark.

Chris Gilbey joined Alberts around the same time, at the start of 1973. Gilbey, a Londoner who had played in small-time bands in the sixties before moving to the other side of the desk, arrived in Australia via South Africa.

CHRIS GILBEY: “Ted had been giving George and Harry a retainer even when they were in England. They came back and I didn’t meet them for quite some time. Ted would have these meetings with them. I was doing—I don’t know what I was doing!—George and Harry were mysteriously making this record at EMI.”

The record George and Harry were mysteriously making was the legendary Marcus Hook Roll Band album, Tales of Old Granddaddy, now a highly-prized collector’s item. This project provided Malcolm and Angus with their blooding in the recording studio, and it was an experience that had a profound effect on Malcolm in particular.

The Marcus Hook Roll Band had its genesis during George and Harry’s final days in England, when a friend called Wally Allen, then working as an engineer for EMI at Abbey Road, got them into the studio to cut a few tracks just for fun. George and Harry returned to Australia soon after, and it wasn’t until EMI’s American affiliate Capitol Records contacted them that they even remembered doing the sessions. Capitol was hot for a track called “Natural Man,” and wanted more. “It was a free trip for Wally who wanted to see Bondi Beach,” George told Glenn A. Baker, “so he scored a ticket and came.

“We went into EMI Sydney for a month and Wally supplied all the booze. We had Harry, myself and my kid brothers Malcolm and Angus. We all got rotten [drunk], except for Angus, who was too young.

“That was the first thing Malcolm and Angus did before AC/DC. We didn’t take it very seriously, so we thought we’d include them to give them an idea of what recording was all about.”

And indeed, Malcolm’s eyes were opened by the experience. Tales of Old Granddaddy not only distanced George and Harry from the Easybeats, drawing them closer to forming Flash and the Pan—the mysterious duo persona with which they would later have Australian and European hits like “Walking in the Rain” and “Hey, St Peter”—it also betrayed seeds of the AC/DC style that was to come. One cut, “Quick Reaction,” was pure riff-driven AC/DC.

Malcolm wasn’t impressed by the fact that the recording process was so piecemeal, so separated, with everything overdubbed and multitracked. That wasn’t the way real rock’n’roll operated. In his view, real rock’n’roll was played by a band, together, as a band. All this technology was obscuring the point of the exercise.

Disillusioned, Malcolm went home and threw his Deep Purple albums in the bin. They were phonies. Not like Chuck Berry, or the Rolling Stones, who were the real thing, who could do it for real, without hiding behind studio trickery. The band Malcolm was getting together would be a rock’n’roll band. It was going to be glam, to be sure, because sequins and makeup were de rigueur at the time, but it would still be rock’n’roll. The idea would prove visionary.

1973, after all, was not a great time for rock’n’roll. It was a mark of the immaturity of the business in Australia that the spirit of glory year 1971 was allowed to dissipate. Even Billy Thorpe, the movement’s spearhead, couldn’t maintain his momentum after that ill-fated trip to England in 1972.

By 1973, the scene was split down the middle. “Commercial” music had taken over the charts. Any new “progressive” bands had to rely on the live circuit to survive. With the arrival of American-style programming, radio had adopted rigidly conservative formats.

The two biggest Australian albums in 1973 both belonged to Brian Cadd, whose Americanisms segued smoothly onto radio playlists. Sherbet, who had won the last ever Battle of the Sounds, the year after Fraternity, were rapidly establishing themselves as teen heart-throbs.

A second wave of bands stormed Melbourne’s “underground” ballrooms, discos and pubs, and the scene was admittedly expanding. But beyond gigs in Adelaide and (to a lesser extent) Sydney, there was nowhere else to go.

Technology was improving, but the talent lagged behind. When Michael Gudinski formed Mushroom Records in 1973, it struggled initially because it lacked genuinely first-rate bands.

The best band of the day was Lobby Loyde’s Coloured Balls, but—typically—they were marginalized and ultimately defeated. Loyde had built on the foundation he’d laid with the Aztecs, and taken it to a logical conclusion. The most profound legacy Billy Thorpe left to Australian rock’n’roll was probably his blithely confrontational attitude, and though the Coloured Balls inherited that tradition, volume for its own sake wasn’t their weapon—they favored blazing dynamism, aggression and finesse. Echoes of this sound can be heard in Australian rock’n’roll to this day, but in 1973, complete with their tough, sharpie image, the Coloured Balls were resisted by the hippies who ran Melbourne music as much as by audiences.

In Sydney in 1973, the new rising band was teenybopper rocker outfit Hush. Sherbet dominated the national scene. It was enough to make Malcolm Young puke.

AC/DC, named by Margaret Young after a warning sign she noticed on her sewing machine, coalesced around the end of 1973, with a line-up comprising Malcolm, Angus, singer Dave Evans, bassist Larry Van Kriedt (a Dutchman, like Harry Vanda) and veteran drummer Colin Burgess (formerly of the Masters Apprentices).

15-year-old Angus had only just left school, which he’d hated. He had started work as a compositor (for porn magazine Ribald, or so he claims), and he wasn’t automatically included in the band. Throughout his last year at school, Angus never had a guitar out of his hands. He would run home and run straight out again to go and jam with his mates. He wouldn’t even change out of his school uniform; it was this image of him, wielding his axe, that inspired Margaret to suggest he take it on stage. Angus was putting together a band of his own called Tantrum when Malcolm asked him to fill the gap in AC/DC where keyboards wouldn’t fit.

Dave Evans, whom Malcolm had met through the Velvet Underground, had obtained his position in the new band more because of the way he looked than the way he sang. He was not a good singer at all, in fact, but Malcolm wanted glitter—he himself dressed like a sort of space cowboy—and Evans had that in spades. As a performer, he was a shameless exhibitionist.

Still unnamed, the band played its debut show in the middle of the bill at a venue on Sydney’s southern beaches, a converted cinema called The Last Picture Show. They played their first show as AC/DC at Chequers, in the city, on New Year’s Eve 1973. No record exists of this show other than Angus’s colorized recollection: “We had been together about two weeks. We had to get up and blast away. From the word go it went great. Everyone thought we were a pack of loonies—you know, who’s been feeding them kids bananas?”

The band’s repertoire at that time consisted of Rolling Stones, Beatles and Chuck Berry songs, maybe some Free, plus a few old blues numbers and a couple of tentative originals.

“I could never sit down with a record and copy it,” said Angus later. “Malcolm had a better ear for analyzing and dissecting. I thought, he could pick it up and I can whip it off him . . . It’s still the same way, I think!”

By April, the rhythm section consisted of Rob Bailey (bass) and Peter Clack (drums). Bailey and Clack had grown as a unit out of Flake, a band that first hit during the radio ban with a version of Trinity’s version of the Band’s version of Dylan’s “Wheels on Fire.” They passed an audition held at George’s new place in well-heeled suburban Epping, and it was this settled line-up that would soon go into the studio to cut a debut single. Angus was wearing a Zorro suit, and the band was holding down a residency at the Hampton Court Hotel in Kings Cross as well as gigging around on the suburban dance circuit.

Harry and George, meantime, were ensconced at EMI with their old Easybeats cohort Stevie Wright, who had been dredged out of the dual indignity of heroin addiction and the cast of Jesus Christ Superstar. Malcolm contributed guitar at these sessions too.

In June, what was probably the first ever press notice of AC/DC appeared in Go-Set. The news article stressed the band’s youth, which it was putting to its advantage. “Most of the groups in Australia are getting on rather than getting it on,” Malcolm sneered, “out of touch with the kids that go to suburban dances.”

The piece also reveals as a lie that AC/DC were innocent of the sexual connotations of their name. Malcolm points out that it refers to electricity, “but if people want to think we’re five camp guys, then that’s okay by us.”

Even Molly Meldrum, Australian music’s foremost apologist, once described early 1974 as its “lowest ebb.” But this was only the lull before the storm, a storm precipitated by the comeback of George, Harry and Stevie with the monumental “Evie,” the first single off Hard Road, the album they’d finished recording.

CHRIS GILBEY: “Everybody had a sense of—it was post-hippie—we’ve decided we don’t want to drop out, we’re going to drop in and make it really work. Of course, the wonderful thing was that the Albert family had this tremendous cash base, so they could afford to play at being the record business in a way no other indy could.”

In its full three-part form, “Evie” was over 14 minutes long, but even so it crashed through the radio barrier on its release in June, and went on to become one of the biggest Australian hits of the year.

If the Easybeats ever had a homecoming, it was the now legendary free show at the Sydney Opera House in June, which had Stevie fronting a band that included not only Harry and George, but also Malcolm. A crowd of 10,000 had to content itself with the sound from a PA system set up on the Opera House steps, since there was no room left in the theater itself. It was typical of the obstinately forward-thinking George that not a single Easybeats oldie was played that night.

AC/DC played that night too. Go-Set commented, “AC/DC opened the show and showed they’re a force to be reckoned with. They play rock’n’roll intelligently, adding their own ideas to sure crowd-pleasers like ‘Heartbreak Hotel,’ ‘No Particular Place to Go’ and ‘Shake, Rattle & Roll.’”

Praising Angus and Malcolm’s dual guitar attack, whilst comparing Dave Evans to David Cassidy, the review concluded that the band “looked great and sounded great. Their material is part original and will undoubtedly prove popular as the band gets about a little more.”

If family ties had given AC/DC a kick-start, George had to let them find their own way from there. Even if he was always looking over their shoulder. When the band was approached by Dennis Laughlin with a management offer, George gave the nod. Laughlin, of course, was the former Sherbet front man and Nova agent who, by 1974, was operating as a lone wolf on Sydney’s southern beaches, running a gig in an old cinema in Cronulla called The Last Picture Show. He always had an eye for the main chance, and he certainly saw a chance in AC/DC. Laughlin grew up around Burwood too, though it was perhaps more important to George that he was a fellow Scot. Laughlin vowed that he would get the band out on the road—beyond Sydney—where a lucrative circuit awaited.

It was apparent by this time that Dave Evans had to be replaced. His onstage antics had become an embarrassment. “We used to kick him [Evans] off stage,” Angus recalled, “and me and Malcolm would just jam on boogies and old Chuck Berry songs, and the band would go down better without him.” Malcolm and Angus had contemplated getting rid of him for some time, but both John Paul Young and future Alberts two-hit-wonder William Shakespeare had declined their offer of the job.

The band was desperately looking out for a new front man when Dennis Laughlin scored them the support spot on the August tour by Lou Reed. Reed was then at the height of his junkie-faggot phase, and AC/DC, with their ambiguous moniker and coy debut single, “Can I Sit Next to You, Girl?,” must have seemed perfectly suited to the bill. And hey, weren’t they George Young’s little brothers? It was in the blood, wasn’t it?

As unremarkable as “Can I Sit Next to You, Girl?” was, it became a minor hit in Perth and Adelaide. As a result, Laughlin was able to arrange gigs there, as well as in Melbourne (then still very much the Australian pop capital), in addition to the Lou Reed shows.

After playing the last show of the tour with Reed in Adelaide, AC/DC played a couple of pub gigs of their own, and then went on to Perth for a six-week season at the city’s top disco, Beethovens, as support act for famous transvestite Carlotta.

Bon saw the band in Adelaide. He was unaware of the strings that had been pulled behind his back. He had recovered sufficiently from his bike accident to be getting around, and was doing odd jobs for Vince, painting his office, putting up posters, driving visiting bands (among other things, Vince was helping a new young band called Orange become Cold Chisel). In touch with George Young, Vince booked AC/DC into Adelaide.

VINCE: “George told me, We need a new singer, and I said, Well, what about Bon? George said, But I heard he had an accident. I said, He’s alright now, and he wants to leave Fraternity, they’re too serious for him. He said, ‘Well, why don’t you suggest it to Malcolm and Angus?’ So I did, and they said, ‘Your old mate? He’s too old!’ I said, ‘He could rock your arse off.’

“I said to Bon, You want to go and check out this AC/DC. He said, Arrgh, they’re just a gimmick band. Anyway, we went out to the Pooraka, went backstage, and I remember Angus said, So you reckon you can rock the arse off us? Bon said, You young kids? You bet! And they said, Well, let’s see, and they arranged a rehearsal at Bruce’s place.”

ROB BAILEY: “Bon and Uncle turned up, and they were like regulars after that. Bon must have seen the opportunity, thought, This is for me, and set about to woo Angus and Malcolm. After gigs, Angus and Malcolm would disappear with Bon. Bon wasn’t silly, he knew where to hit.”

The popular myth that Bon had first been employed by AC/DC as their driver—a myth propagated by the band itself as much as anyone—must have had its origins here, as Bon played host to Malcolm and Angus, all of them getting around in the old Holden Bon had recently bought for $90.

“I knew their manager,” Bon himself said later in the film Let There Be Rock. “I’d never seen the band before, I’d never even heard of AC/DC, and their manager said, Just stand here, and the band comes on in two minutes, and there’s this little guy, in a school uniform, going crazy, and I laughed.”

“I took the opportunity to explain to them how much better I was than the drongo they had singing for them,” Bon said on another occasion. “So they gave me a chance to prove it, and there I was.”

Angus, Malcolm and Laughlin went down to the cellar where an aggregation consisting of Bon, Bruce Howe, guitarist Mauri Berg, John Freeman and Uncle were half-arsedly rehearsing. These other guys, though, were unaware that what was going on was virtually an audition for Bon.

BRUCE HOWE: “Angus and Malcolm picked up guitars and started playing and I started playing bass, and I thought, Fuck me dead, these guys are just so together, with their rhythms, each other; they were almost telepathic. It was one of the best impromptu musical buzzes I’d had in ages.”

Bon pulled out all the stops. Laughlin offered him the job on the spot. Bon said he’d think about it while the band was in Perth.

Bon was torn. He went down to the docks and, gazing out over the sea, mulled over everything—Irene, Fraternity, AC/DC. The easiest decision to make was that he didn’t want to spend the rest of his life as a working stiff. Next, he wanted out of Fraternity, despite the ties. And he wanted in with AC/DC. He knew it could work. It had worked for Alex Harvey, one of his heroes. The great Scottish rocker was already past thirty when he finally broke through, thanks to a new young backing band.

The hard part was Irene. Bon had never given up hope that his marriage might yet be resurrected, and he didn’t want to abandon that possibility. But in the end, he knew he had to. As Irene put it: “I was ready to settle down. Bon still wanted to be famous.”

BRUCE: “He wanted to do it, but he wanted to do it unencumbered by emotional baggage. Bon knew, because he’d done it before, you’ve got to be in a position where there’s no wives, no children, you’ve just got to be able to get up and take the opportunities as they come.”

After a few weeks in Perth, Dave Evans took to calling in sick. He was drinking a lot. Dennis Laughlin, who himself would occasionally fill in for Evans, rang Bon to reiterate the offer. Bon rang back later to say he’d do it. The band would be passing through Adelaide on their way back to Sydney anyway, so they could get together then. Evans was sent packing. He went on only to enjoy fifteen seconds of fame in 1976, fronting Rabbit on their immortal “Too Much Rock’n’roll.” Bon got up with AC/DC for the first time at the Pooraka.

“The only rehearsal we had was just sitting around an hour before the gig, pulling out every rock’n’roll song we knew,” Angus said. “When we finally got there Bon downed about two bottles of bourbon with dope, coke, speed, and says, Right, I’m ready, and he was too. He was fighting fit. There was this immediate transformation and he was running around with his wife’s knickers on, yelling at the audience. It was a magic moment. He said it made him feel young again.”

VINCE: “The next day, Bon came around to my office, and said, Whaddya reckon? I said, Well, you know, I like them. I think they’re great and I think they’re going to be big. I asked him, Why? He said, Because I’m going to join them. I said, When are you leaving? He said, Today.”

DENNIS LAUGHLIN: “I went round and picked Bon up at his place with Irene. And that was it, that was the end of the marriage too.”

VINCE: “He just packed his bags. He came around with them in the car, he came around to say goodbye, and he wound down the window and said, Seeya later. And that was that.”