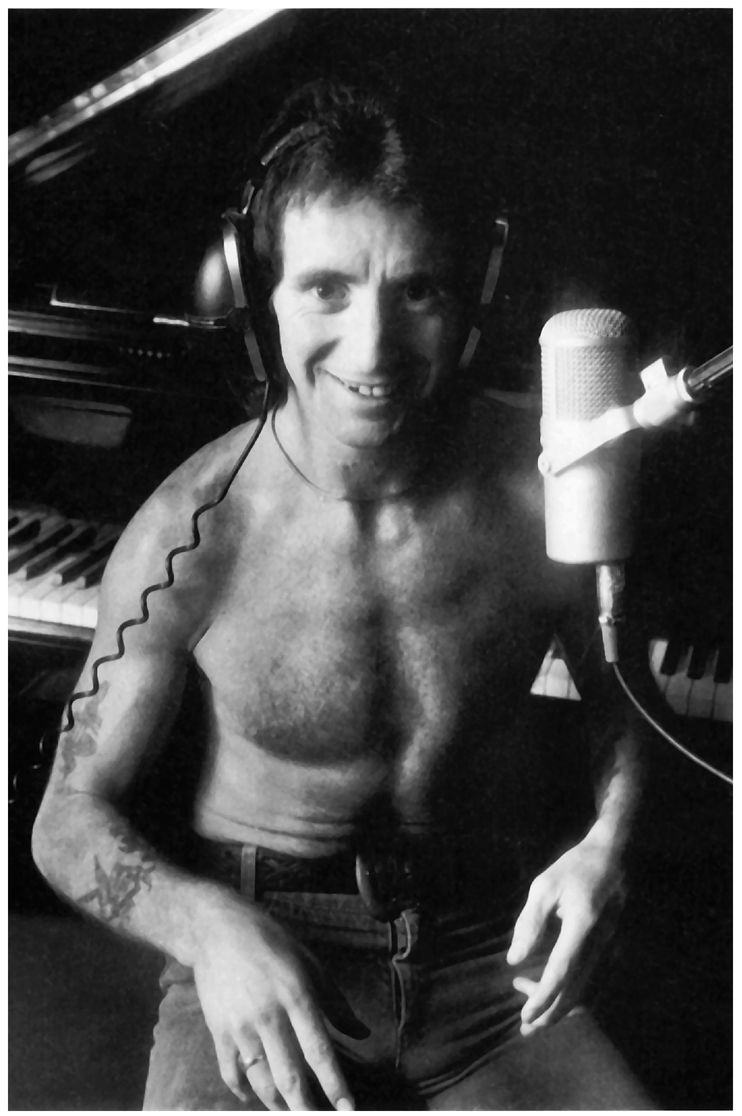

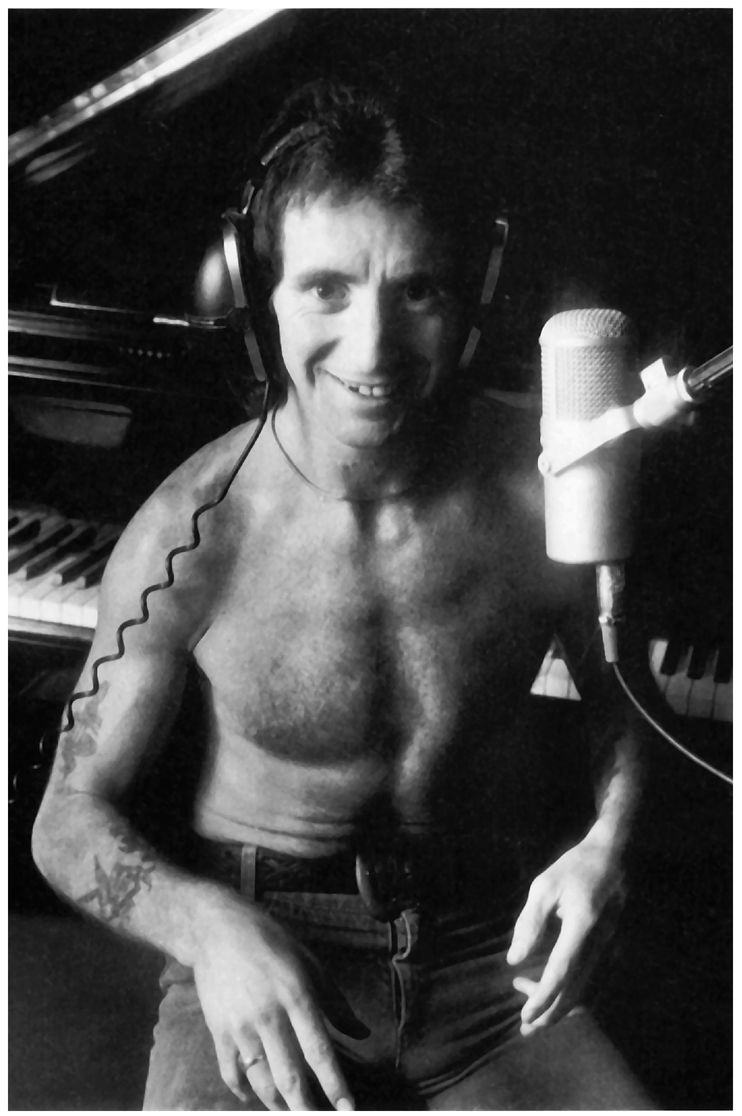

In the studio at Alberts, March 1976, during the recording of Dirty Deeds Done Dirt Cheap. (Philip Morris)

10. SYDNEY

“The Lifesaver was an ungilded palace of rock’n’rolling, easy-going degeneracy,” Anthony O’Grady wrote in RAM of the venue which in the second half of the seventies was “the most prestigious place in Sydney for top and soon-to-be top Australian bands.”

“And if no one could exactly remember the details the next day—like exactly how or why they ended up in bed with Mandrax Margaret, Amphetamine Annie or Tom, Dick or Harry from the band, well, no blame on either side for the oblivion of the night before. In fact, the bed-hop after the bop caused the place to be nicknamed the Wifeswapper.”

Sydney’s scene at the time was very different to Melbourne’s. In the early eighties, as its pub circuit flourished, Sydney superseded Melbourne as the center of rock’n’roll in Australia, but in 1975 rock’n’roll was only just taking root in Sydney.

Initially, while the Youngs went back to Burwood, the rest of the band and crew stayed at the Squire Inn at Bondi Junction. Everyone was happy, not least of all because they were in the studio, recording the new album. Coral Browning was on the case in England. Bon was happy just to be away from Melbourne, free to lick his wounds. Of course, it didn’t help that directly across the road from the Squire Inn stood the Lifesaver (this was before both buildings was demolished to make way for a shopping center and car park).

The Bondi Lifesaver is as much a part of Australian rock lore as the Largs Pier, Sunbury or the TF Much Ballroom. Though it had faded by 1979, in 1975 it was a hotbed, its glory years just beginning.

“It was the sort of place where you’d be there three nights a week, even if there wasn’t always bands on,” said Helen Carter, a longtime regular. “It was a bar-restaurant, with music, which meant that you would get there at six, and didn’t leave until two.”

With his room across the road, Bon made a virtual office out of the Lifesaver, where the band also played on occasion. He was able to enjoy his celebrity, because Sydney was now for AC/DC what it had earlier been for the Valentines—less hysterical, less aggravating than Melbourne. Obviously Bon hadn’t learned his lesson about jailbait, though, because he took up with the 16-year-old Helen Carter. But then, the gorgeous young Helen wasn’t a fraction of the trouble Judy King had been.

Helen, who grew up in Bondi, had been going to pubs since she was 13 or 14, and she was a smart kid. She would later form the postpunk agit-rock band Do-Re-Mi, who scored in 1985 with the feminist anthem “Man Overboard.”

HELEN CARTER: “I saw AC/DC at the Lifesaver—I must have seen them a couple of times—and I just decided one night, I wanted to meet Bon, I wanted to talk to him about what was going on. I guess I thought that sex would be part of it, but I can’t say honestly that I didn’t think I wouldn’t like to sleep with him. So I just walked up one night, and it was quite late, I had to go, so he said, Well, I’ll ring you tomorrow. I thought, Sure . . .

“Anyway, he rings up, and I was at work, so he came and visited me where I worked, at a jeans shop, and he took me out for lunch, so you know, he was courteous I suppose. He always had that, a gentlemanly manner.

“He said, Come up to the gig tonight. So I went up and I saw the gig, and I don’t remember exactly what happened, but I know that night we ended up going back to the hotel and I stayed there. And I stayed there quite a lot; and when they went to the Sebel, I stayed there a lot too.

“When they were staying in this Bondi Junction place, they were all in one room. Bon had the double bed because he was the oldest. Everyone else had single beds. But we would sleep together, with everybody else in the room. That kind of irked me a bit, because it was something I felt slightly embarrassed about, but he understood that, and certainly never forced me to do anything I didn’t want to.

“He was incredibly gentle. He realized I’d never seen any of this stuff before—not that it was so outrageous, there was a lot of drinking, but there wasn’t any drugs.

“The boys in the band—the singer in a lot of bands is frequently apart, you’re not actually involved in the equipment or anything like that. Bon very much kept to himself. It was almost as if there was an invisible wall. The boys in the band pretty much did their own thing. But he loved them.

“He was a really hilarious person too; he was really very funny. Cheeky. He would do all sorts of things just to amuse himself and me. He had a very stable view. And he was meticulous, the way he dressed and groomed. Very plain—sleeveless shirt, a pair of jeans—but always perfectly laundered. Belt, studs . . . that was it, that was the uniform. And he always washed his hair. Dried it properly. He was very proud of his hair. He wasn’t just the archetypal grub rock’n’roller.”

Bon and Helen hung out. They went dancing, Helen lurching on her clogs, at Ruffles disco, which was on the roof of the Squire. And they went to the Lifesaver, across the road. Sometimes AC/DC played there; other times it was bands like Dragon, Buffalo, Cold Chisel or the Ted Mulry Gang.

HELEN: “The stuff that used to go on in that backstage room at the Lifesaver! The room was minute, and they always had the most unbelievable groupies, the loyalty was unbelievable. Not so much a lot of girls, but regular. One in particular, I just couldn’t believe what she would do. People would have sex with this girl, in the dressing room. This was a normal thing. Not just blow-jobs either, but penetration, actual fucking.

“You’d just be standing there trying to hold a normal conversation, and Bon would turn his back and say, Don’t look. The girl would just lift her dress and they’d start doing it. You’d think it couldn’t have been any fun for anybody.

“I guess for Bon, that was part of the reason why he tried to set an example. Although, God, you couldn’t have got a worse role model for drinking. I saw him drunk a lot, but he never lost control. He was actually a big sooky drunk, like some people get, just subdued, you know. Not at all violent. He would rather have a nice soft relationship. He wasn’t a wild man lovemaker or anything; to a certain degree that wasn’t the only thing on his mind either, despite his songs, which are all just sex or rock’n’roll.

“He loved women, he used to love the attention of women, he loved to have lots of them around. I can say this now and it’s probably crap because I look at that sort of behavior and think, Well . . . but you see, the difference was, he didn’t treat anybody like shit. Even then, when I was 16 and pretty naive myself, if there was any of that we-just-fuck-’em-and-dump ’em attitude, I would have thought, Oh, that’s not very nice. But there was none of that.

“Bon would say, Look, if I seem a bit strange sometimes, don’t get upset, talk to me about it later. It was obvious even then he was aware there was some kind of public persona that he had to uphold as soon as he stepped outside his hotel room. But in private, he used to say things like . . . You know, he always used to wear those sleeveless vests, and he’d stand in front of the mirror in the hotel room flexing his muscles. I’d be just sort of sitting there looking at him. He’d say, Do you think it looks good? You know, he was as vain as any other man I’ve ever known. And I’d say, Sure. He said, You know, I buy them two sizes too small so it makes my muscles look bigger. He was really crucially and sometimes a bit embarrassedly aware of what was expected of him, or what he thought was part of the performance, even though he was very sincere about it.

“What I’m saying is, he was a professional.”

AC/DC started to make an impression in Sydney, attracting much the same sort of disenchanted kids they had done in Melbourne. Hurstville Rock, a no-alcohol dance held every Saturday night in the local Civic Hall, became a stronghold gig. One witness recalls, “When AC/DC played it was always huge. You could stand in the middle of the dance floor, and it would be bouncing up and down.

“There used to be this thing between the Westie rockers, who’d come because they liked AC/DC, and everybody else, because we thought AC/DC belonged to us. The audience was mainly surfies, you know. Thongs, jeans, Hawaiian shirts. All these underage people would sneak in, there was no grog allowed but there was always plenty going round. And joints—that was where I got stoned for the first time. People would just pass joints around! You’d get drunk, stoned and you’d chat up girls. AC/DC were great.”

Tireless roadwork was drilling the band into a lean, mean rock’n’roll machine. Malcolm told RAM (before he virtually stopped talking to the press altogether): “We used to worry about playing what was on the album—we used to play spot on—note for note off the album. But the people weren’t getting off on it. Then George said, Don’t play the songs, play to the people.”

Bon was also taking his role as songwriter more seriously.

HELEN: “The thing about Bon was that he really did think a lot about what he was doing. He took it very seriously. He was a very meticulous person. So as a writer, he wouldn’t just blurt stuff out. It would be very thought out.

“Bon would leave his lyric notebooks lying around, and I was fascinated by the way he would always write in capital letters. He’d have everything really neatly written out.

“And I think he found writing not an easy thing. Angus and Malcolm used to write a lot of music; they’d just sit down and jam and come up with stuff. So there was a constant flow of material being put to Bon, to write, and I think in some ways that was quite a pressure for him.”

The band spent every spare moment during July at Alberts, mostly through the night. To Malcolm and Angus it was just like being back home. George was there, running the show with Harry, his redoubtable partner. Also there, as general trouble-shooter, was Sammy Horsburgh, the former Easybeats tour manager who married Margaret Young.

MARK EVANS: “It had a real family atmosphere. The Youngs are real Scottish working class, really good strong family, you know, staunch. Very hard though. Every time I’d go round there—and we used to play a lot of cards, after gigs, we used to play poker—there’s seven brothers, and every time one or two or three or four of them would be punching the shit out of each other. Every time, without fail, someone would be having a brawl!”

The old Boomerang House on King Street in central Sydney, where Alberts studio was then located, was owned by the Alberts family. It had housed radio station 2UW, which the family also owned. Alberts Music was also there, though the studio wasn’t built until 1975. That was Studio One; other studios were added over the next few years.

With a bare brick wall adjoining it, Studio One looked more like a squat than anything at the cutting edge of technology. And it wasn’t that, either.

EVANS: “It was very small—we used to record in the side room, had two Marshall stacks and bass-rig, pointing towards the wall and miked up, and in what used to be the kitchen, drums in there—everything put down at once, generally the fire was in the first couple of takes.”

What Alberts had that money can’t buy was a vibe, an ambience. In recording studios, the vibe is something that goes down on tape—that’s why it’s so important. Alberts had a vibe merely because of the presence of George and Harry, astute manipulators of studio psychopolitics who consistently drew the best out of performers. Their other great strength, as Chris Gilbey put it, was that “they were tremendously good song men.” In other words, they had ears for a hit.

TED MULRY: “You didn’t go into Alberts saying, Let’s record this song. You were going in there to come up with another hit. And that was everybody’s attitude, the buzz going round. You went in to come out with a hit.”

“George produces our material not just because he’s our brother,” Angus said. “He thinks we’re good. If we were shithouse he wouldn’t do it. But it’s nice and easy-going in Alberts’ own studio. When you get in there you feel relaxed and at ease.”

Bon told Juke, “He’s like a brother, no, a father to the group. He helps us with our writing. He doesn’t tell us what to do, he just shows us how to get more out of the things we start.”

AC/DC were much better prepared for recording their second album—tighter and more confident; they even had a few rough ideas to go in with.

Five more new songs were cut during July (“High Voltage” and “The Jack” were already in the can). Alongside a re-recorded “Can I Sit Next to You, Girl,” and a version of Chuck Berry’s “School Days,” they turned out “Long Way to the Top,” “Rock’n’roll Singer,” “Live Wire,” “TNT” and “Rocker,” which complete the album’s track listing. None of it seems ill-considered.

EVANS: “Malcolm and Angus would come up with riffs and all that, and then we’d go into the studio. Malcolm and George would sit down at the piano and work it out. Malcolm and Angus would have the barest bones of a song, the riff and different bits, and George would hammer it into a tune.

“Bon would be in and out when the band was recording backing tracks. Once the backing track was done, he would literally be locked in the kitchen there at Alberts, and come out with a finished song.”

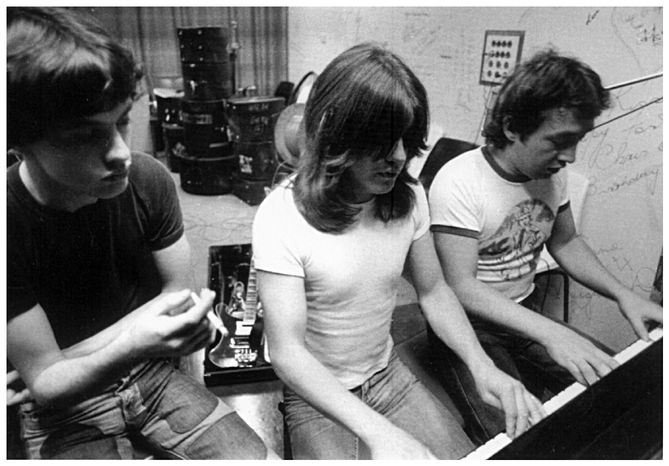

Angus once said, “[George would] take our meanest song and try it out on keyboards with arrangements like 10cc or even Mantovani. If it was passed, the structure was proven, then we took it away and dirtied it up.”

AC/DC would record backing tracks live in the studio—sound spilling everywhere because the band played so loud—and then vocals and guitar solos were overdubbed. George and Harry were careful to give the group its head, but at the same time, they knew when to stop.

MICHAEL BROWNING: “Yeah, and then just embellish it a bit. George and Harry’s most important criterion was rhythm, the whole thing had to just feel right. If you listen to those records today, they feel good.”

CHRIS GILBEY: “The great thing George and Harry taught me, as a producer, was that if you’ve got a good rhythm track, you’ve got the beginnings of a record. If you don’t, you’ve got nothing.”

TED MULRY: “When AC/DC were recording, you’d walk into a session, and Angus would be on top of the quad boxes, in the studio. He couldn’t just sit there, he’d be running around jumping up and down like it was a live performance.”

BROWNING: “Malcolm used to come up with a lot of titles. He’d sort of come up with a title like “TNT,” and then he’d play some chords to fit that title, and a lot of the songs were just developed that way. Bon would go away and write a song about TNT, or this or that.”

In his notebooks, Bon had lyric ideas to put to music. Locked in the kitchen, he ran lines through his head one last time, mouthing them out, getting it right. As a singer, Bon was a screecher (there are those who believe his voice was never the same after the accident that did so much damage to his neck and jaw), but like Sinatra or Dylan, his greatness was in his phrasing. And it was the interplay between his phrasing and his words, in their economy, that proved just how seriously he took songwriting.

Angus, Malcolm, and George Young in the studio, Alberts, Sydney, March 25, 1976, during the sessions for Dirty Deeds Done Dirt Cheap. Angus: “George would take our meanest song and try it out on keyboards with arrangements like Mantovani. If it was passed, the structure was proven, we took it away and dirtied it up.” (Philip Morris)

HELEN: “Looking through his lyric books, you would see different versions of things. The sort of lyrics they were, you think, Oh, any old dickhead could write that. But it’s not true. Even the simplest of lyrics, his timing and meter, he spent a lot of time on.”

Bon told Countdown: “Things fall into place. Sometimes. You gotta keep your eyes and ears open for lines and words and stuff . . . ideas, just pictures, you know.”

TNT was the album that really introduced AC/DC as a band. It still contained a few naff tracks, but its forcefulness was undeniable. If it was as impatient as it was bold, even that was impressive. 1975 needed rock’n’roll like this. And certainly, the album’s one-two opening punch is as powerful as any ever recorded, with Bon virtually encapsulating his entire life in “Long Way to the Top” and “Rock’n’roll Singer.”

“‘Long Way to the Top’ started as a guitar jam in A,” Angus later explained. “It was just that little jam and George thought it cooked. And then Bon had the scribble which turned into the lyrics.”

Completing side one, “The Jack” overplayed its card-table metaphor, while “Live Wire” was as good a piece of braggadocio as AC/DC produced. “TNT,” the album’s title track which opens side two, was on a par with “High Voltage”—fair but disposable. Next to “Can I Sit Next to You, Girl” and “School Days,” “Rocker” was hilariously frenetic.

With the new album in the can, sales of High Voltage were still strong, boosted by the release of the new single with the same title. The band appeared on Countdown, with Bon doing his Tarzan routine wearing nothing but a lap-lap.

GILBEY: “At that time, we’d done what we thought were phenomenal units, about 70,000 on it, and that was unheard of, and then the single “High Voltage” took the album up to 120-125,000, and we thought, My God!

“We didn’t think AC/DC would become a world-wide phenomenon the way they have. We were all just occupied, tight-focus, on making the act survive. It was just, get a record away. Keep having hits. Try and keep moving. And then it was, Hey, let’s get outside the country and see if we can sell it overseas. That was the next step.”

Chris Gilbey was possibly thinking this way when everyone else was thinking about England because he himself had already taken a knock-back on AC/DC overseas. When he went to MIDEM in January 1975, representing Alberts generally, he found more people interested in bubblegum pop star William Shakespeare! George, in turn, didn’t mind that Gilbey was concentrating on Australia, because Michael Browning was chipping away in England. Browning had sent Coral a copy of the video AC/DC had shot at their Melbourne Festival Hall Queen’s Birthday concert, and she was hawking it around London.

To promote a free show at Sydney’s Victoria Park in early September, which on the back of the “High Voltage” single would serve as a Sydney launch for AC/DC, Chris Gilbey devised the “Your mother won’t like them” advertising campaign for radio station 2SM. It worked a treat. The single peaked at number six nationally.

GILBEY: “It was like, instant attitude. Nowadays, everything is premeditated. Back then, we didn’t have to philosophize, and come up with a psychological profile of the consumer, to figure out why it was we wanted to sell a bad-boy image in order to have those kids that were alienated from their parents love this group. We just thought, Hey, this is exciting, this is cool. Either you had it or you didn’t have it. Rose Tattoo, either you have it or you don’t.”

It was another cold Sunday afternoon when AC/DC played at Victoria Park with Stevie Wright and Ross (“I am Pegasus”) Ryan. The show was unremarkable—as usual, the band blew everyone away—save for the fact that it saw Angus climb astride Bon’s shoulders for the first time.

Bon had obviously climbed back in the saddle because, as Angus said, “That notorious leader of thieves and vagabonds, Bon Scott, to celebrate the success of the show in Sydney, went out and got a new tattoo and pierced his nipples for earrings. The other boys celebrated in other ways.”

The band was right on target.

In September, AC/DC went back down to Melbourne to renew their expired agreement with Michael Browning—a five-year management contract was signed—and to get it together for an extensive national tour to promote the pre-Christmas release of the new album. As it turned out, the album wouldn’t eventually be released till February, but this is rock’n’roll, after all.

Bites were being registered overseas. Bon wrote to Mary, “A&M is wrapped in the band as is John Peel the DJ. Reckons we’re the band England needs and we agree.” He also wrote to Irene, “I’m not doing too bad on the booze thing these days and am getting drunk quite regularly. But I’m a peaceful drunk now. Have I still got any friends in Adelaide?”

Starting in Perth, the tour would take the band all over Australia before winding up in Sydney on Christmas Eve. Before heading to Perth, the band played a few shows in Melbourne.

Booked to play a week of free lunchtime gigs in the Miss Myer department of the big Myers store in the city, the band had barely started their first set on the first day when they were overrun by hysterical girls (reports vary from 600 to 5,000). The shop and its fixtures were turned upside down; strangely, a shoplifting frenzy was not reported. The rest of the week was promptly cancelled.

MARK EVANS: “It was just bedlam. It was probably the only time I thought one of us was going to get hurt. It was really scary.”

The band had to run for their lives. Bon, however, even as he fled, still managed to sneak a peek over the saloon doors of the changing rooms.

A Premier Artists worksheet for the band for the second week of September saw them playing six gigs, plus recording an episode of Countdown, between the Wednesday and Saturday, for total earnings of $3,610, which included a $160 performance fee from Countdown. Certainly, it made their old $60 per week pay packet seem inadequate.

At an average of $600 per gig, AC/DC played the South Side Six on Wednesday and the Matthew Flinders Hotel on Thursday, both suburban beer-barns, where the band played one set between 10 p.m. and 11:30. At the Matthew Flinders, a scuffle in front of the stage involving Angus cost drummer Phil Rudd a broken thumb, necessitating an immediate stand-in. On the Friday, with old drummer Colin Burgess on Rudd’s stool, the band played a free show at the Eastlands Shopping Center in Ringwood, between 6:00 and 7:00, and then later they appeared at the International Hotel. At 6:00 on Saturday night, the band recorded an appearance on Countdown, then played the Tarmac Hotel between 10:00 and 11:30 and then the Hard Rock Cafe between 1:30 and 3:00. On Sunday, the band flew to Perth.

Bon visited his mum and dad in Perth. Chick and Isa were very impressed by the boys. It was the first time they’d all met each other, and they were such nice boys, Isa thought.

The band worked their way back to Melbourne playing through South Australia, visiting even the towns of the dreaded Iron Triangle again.

Right on the back of recording TNT, the band was in blistering form, but it didn’t always get the reaction it might have liked.

“We had been on a tour with AC/DC which led to our first recording . . . our big break,” Angels singer Doc Neeson recalled. “And because we were a covers band and they were an original band, we were getting encores and they were getting booed. People knew our songs and thought that they were a dirty heavy metal band.” AC/DC, nonetheless, went home and told George about this hot new band called the Keystone Angels and, as the Angels, they would serve Alberts well.

MARK EVANS: “The band itself wasn’t hyped, it was good, a good band; but the mechanics of the thing, it was hyped-up, there’s no question about that. I don’t know any successful band that isn’t. But if it had have been left to the reaction from live gigs alone, we would have been struggling.”

The fact that Angus was pushed as the focal point didn’t bother Bon. Armed with an axe and a fag and dressed in his school uniform, Angus provided an image so readily identifiable, it became a symbol for the band. In fact, Bon was almost relieved that some of the heat was off him on stage. Jealousies simply weren’t possible anyway. The power structure within the band was set, and if you didn’t like it . . . Nobody apart from Malcolm and Angus was indispensable, it seems, including Bon. And though Bon was granted special dispensations, he almost went too far on occasion. Like when he OD’d. But even then, the Youngs couldn’t think of sacking him. Blood was thicker than water, after all.

Bon was elusive, and though he could be annoying on a day-to-day level, he always came through in the end. He was always running late, and he might often be the worse for wear, but he never once failed to show, and he always gave everything he had.

Back at the Freeway Gardens Motel in Melbourne, where the band now based itself, Bon was still likely to wander off by himself. But more often than not he was hanging out with Pat Pickett. Pickett had been living in provincial Geelong, employed at the local meatworks, when he heard about AC/DC. He immediately made a beeline for Melbourne. He joined the band’s crew in a nebulous role—similar to that he had enjoyed with Fraternity—as Bon’s consort, his partner in crime. Bon’s frame of mind was pure reckless abandon.

MARK EVANS: “We were always looking after him, looking out for him, and we were only kids ourselves. You’d say, Hey, where’s Bon? I remember carrying Bon home and putting him into bed. But he had this thing about him where you wanted to take care of him.

“You could see his charm kicking in. You could also see Bon Scott the singer of AC/DC kicking in when the press was around, you know.”

The Freeway Gardens, a shabby motel at the mouth of the Tullamarine Freeway in North Melbourne—devoid of any sort of garden—was a haven for many bands, including the Ted Mulry Gang.

HERM KOVAC: “Bon used to carry around this little shaving kit. That was his whole baggage. It contained a toothbrush, toothpaste, one pair of jocks and one pair of socks. That was it. He’d wear his jeans till he might wash them at the hotel, and so he’d just get around in his jocks till they were dry. But otherwise, he’d have a pair of jocks and socks on the go, and he’d wash them each night in the sink, hanging them up in the bathroom, and get the fresh pair out of the little bag. He’d rotate them. He traveled very lightly.”

MARK EVANS: “He would do anything. I remember one time he made this bet. It was the middle of winter in Melbourne and he said he’d dive into the swimming pool. Someone took him on for five dollars. A stupid bet. He said, Make it ten. So we went up to the third floor, the balcony, and he just dove straight in. Got out, Where’s my ten bucks? He’d do these things that were just over the top.”

Mark didn’t know Bon had a history of high diving.

The debauchery of Lansdowne Road continued unabated at the Freeway Gardens. The band, after all, was even bigger now. And so, it seems, were some of the fans. It was at the Freeway Gardens that Bon met Rosie, subject of the all-time great paean to large ladies, “Whole Lotta Rosie.” The band held in very high esteem anything that was what they called “depraved,” “evil” or “filthy.” Put Pat Pickett and Bon together and the conversation would take a seriously funny downward turn. Scatology was a favored topic, but that was just the beginning. The band ran an ongoing competition—the prize being booze which they would all hoe into—to see who could pull off the most disgusting, depraved, filthy act.

Bon’s bedding of Rosie was a big winner in these stakes, but as the lyrics to the song suggest, he derived a lot more pleasure from the experience—“Whole Lotta Rosie” is actually very affectionate—than the band might have imagined.

Rosie was a Tasmanian mountain woman who had started showing up at gigs. An open challenge was thus issued.

PAT PICKETT: “We were sharing a room at the Freeway Gardens, and I woke up one morning and looked over at Bon’s bed and I thought, Jeez, he’s done it! There was this huge pile of blubber lying there, but I could see underneath it, this tiny little arm with tattoos on it was sticking out!”

EVANS: “The one myth about the band which was actually pretty true was the amount of females we used to get hold of. It was ridiculous. I used to be fairly lucky, but I was nothing on Bon. He had four days in a row where he got what we called a trifecta, three different girls each day for four days in a row. The man was a genius, I don’t know how he did it. He had a huge . . .”

Penis is the word that might complete that sentence. At least several reports suggest that Bon was extremely well hung. He liked to show it off too, dressing all to one side in jeans that were inevitably almost sprayed on.

EVANS: “This other myth, the image the band had as this heavy drinking, you know, brawling bunch, it couldn’t be further from the truth. We never got thrown out of one hotel.

“Bon didn’t get into any more trouble than your usual bloke on the road. The whole thing was this huge image. There were a couple of instances, a couple. I remember once at the Matthew Flinders, Angus, because he used to spin around on the dance floor, a couple of guys started kicking into him. I remember Pat, Phil and myself jumping off the stage, and getting into that. Phil actually broke his thumb, and so we had to get another drummer for a while, when we were in Perth, we had to get Colin Burgess back.

“But Bon, you could hit him over the head with a baseball bat, and he’d just say, Hey, what are you doing? But if you hit someone he was with with a baseball bat, you couldn’t hide anywhere. Ladies particularly. Guys, he might say, You asked for it. If one of the guys in the band got into trouble, Bon would tell them the next day, You were an idiot last night. But if it was someone you were with who obviously couldn’t take care of themselves, my God!”

Pat Pickett remembers a time when Bon was at a pub with Irene, who moved to Melbourne, and a guy was hassling them, perhaps just because Bon was Bon. The guy was a well known hard man. Bon ignored him, until he went too far. As they were leaving the pub, the guy pulled Irene’s ponytail. Bon had a breaking point, and he had just reached it. He took the guy outside and gave him what witnesses remember as a fist-beating to within an inch of his life.

EVANS: “He was really a pretty mild mannered sort of guy. I mean, I never saw him lose his temper. He had this equilibrium, and he was very, very polite, a real gentleman. Once I saw him get the shits, and it was the strangest thing . . .

“The band appeared on the TV Week 1975 King Of Pop awards show . . . We played live, and Bon had a terrible time, everything went wrong for him; the mike lead got caught in his shoes, everything. When we got off stage, we went downstairs, and we had to break the lock on the door to get into the bar. There were just all these stacks of TV Week there, with [Sherbet singer] Daryl Braithwaite on the cover, the King of Pop. Bon was just standing there staring at them, and he said, Have a fuckin’ look at this! And then he started just laughing, maniacally, he said, I don’t believe this, and he started ripping up all the magazines. And then, from that point on that night, he was the most uncouth, awful, rude person I’ve ever seen. To the point where he took this turkey off the table and was drinking champagne out of it. He just had this turkey under his arm, drinking out of it, offering it to everyone. Something snapped, that one time.”

The band headed out to play rural Victoria, and then ran through Sydney, before returning to Melbourne at the start of November to play a special Melbourne Cup Day show at Festival Hall. Hush supported.

Michael Browning, meantime, was in London. Atlantic Records had gone crazy for AC/DC. A deal would be struck. The album would be released, and the band would go over, sometime in the new year.

All November was spent on the road. The bus was in service when distances weren’t too great, and speed not of the essence. After Cup Day, the band spent a week in Adelaide, then toured through the deep north of Queensland. Back in Sydney, they played at the opulent State Theatre on November 30. The first two weeks of December were spent in and out of Sydney, swinging through Canberra, before making a quick dash to Brisbane to play a Festival Hall show on the 14th.

It was a hectic time, and Bon was obviously feeling the strain. He wrote to Irene:

What a cunt of a night. Just got back from Canberra a day early and no one is expecting us up until tomorrow. Got no booze, no dope and no body except my own to play with. Shit. And to top it off I left my black book in the bus, which broke down in Canberra . . .

I reckon we’d have to be the hottest band in the country at the moment. Not bad for a 29-year-old 3rd-time-round has-been.

I don’t care if I never get a divorce cause I’m not planning on marrying again unless she’s a millionaire and I think my chances of finding one are scarce. But when I pull out my photy album I like saying, And this is my wife. They all fancy you and tell me what taste in spunk I’ve got . . .

I’m going through a fucking funny period at the moment. Hope you don’t mind a heart balm letter. Don’t wanna settle with anybody because I’m always on the road and won’t be here long and on the other hand there’s twenty to thirty chicks a day I can have the choice of fucking but I can’t stand that either. Mixed up. I like to be touring all the time just to keep my mind off personal happenings. Become a drunkard again and I can’t go through a day without a smoke of hippie stuff. I just wanna get a lot of money soon so I can at least change a few little things about myself (more booze and dope). Not really. I just wanna be famous I guess. Just so when people talk about you it’s good things they say. That’s all I want. But right now I’m just lonely.

After Brisbane, AC/DC worked their way down the coast to reach Sydney by Christmas Eve, to play a big shebang at the Royal Showgrounds. Bon spent Christmas with the Youngs, then flew to Adelaide to spend some time with Irene and Graeme, and his girlfriend Faye. “My wife and her boyfriend, that is,” he wrote to Maria, from whom he had received an unexpected Christmas card. “Graeme wants to marry my sister-in-law. I’m saying nothing.” Bon also dealt with some legal matters in Adelaide pertaining to his bike accident. He was still paying off bills.

The band played in Adelaide on New Year’s Day. Again, as Molly Meldrum reported in his column in Truth, “The street punk kids of Australian rock and roll, AC/DC, were the cause of a minor riot.” The band had the power cut on them and Bon, inevitably, incited a storming of the stage in protest. “Power or no power, they were not going to be deterred,” Molly went on. “Because, would you believe, Bon Scott appeared in the middle of the crowd, on someone’s shoulders, playing bagpipes!”

Bon wrote further to Maria:

I’m out on the road again but this time between Melbourne and Adelaide on the coast route. It’ll be the third town tonight and there’s twenty-one more to go. We’ve had a week off between Xmas/NY but now it’s back to work. Got a couple of weeks off after this tour to record and tie up all the loose ends before leaving for England.

All this touring has worn me out. But it’s selling a lot of records and I’m seeing a lot of the country and people that you don’t realize exist, so it can’t be too bad.

I’m finally making money, Maria. About $500 a week and it’s all in the bank . . . I just hope I’m not still stupid cause now I can make a good start at doing something good. Don’t know what though. I haven’t finished rocking yet and that’s all I want to do right now.

With the Atlantic deal now finalized, the rumor was that AC/DC would support labelmates ZZ Top on a British tour to coincide with the release of their first album; then maybe even do something with the Stones, who were also on Atlantic. Either way, the band’s departure was now certain. It was just a matter of exactly when.

Bon had dreamed as a boy of leading a pipe band, marching beside it swinging the baton, feeling the sounds flow through him, feeling responsible and proud, the agent of so much joy as the drone and flutter reverberated in the air all around him. Now the dream was coming true.

A performance through the middle of Melbourne, on the back of a flat-top truck, was arranged by Countdown so they could shoot a video of “Long Way to the Top,” AC/DC’s new single. Three professional pipers accompanied the band.

This was different to what Bon had originally envisaged, but it was better. Bon was singing his own song. It was rock’n’roll—and it was the pipes.

Traffic stopped as the boys drove slowly through the city and fans ran alongside to catch a glimpse of their idols. Stomping along the length of the moving truck’s tray-top (just like Elvis), Bon looked up to see the buildings of Melbourne passing above him under a blue sky and looked down at the adoring faces, and sensed everyhow the power of the music. It infused all his senses, his own body was as if wired, responding involuntarily. Bon was swimming with the power. This was what he lived for.

“Long Way to the Top” has become an anthem. Certainly, it was AC/ DC’s best single to date. Bon was best when he was working to his own brief, rather than writing to order—he expressed himself more honestly, more evocatively.

In “Long Way to the Top,” it’s as if Bon acknowledges he’s living on borrowed time, and luckily at that. But even then, or perhaps for that very reason, the song remains celebratory.

At the end of January, “Long Way to the Top” peaked at number five. Three singles, three hits, and each outperforming the last—it’s a record any act would envy.

When the album was released, sent out to the media wrapped in a pair of ladies knickers, it sold 11,000 in the first week, and shot to the number two spot, kept out only by Bob Dylan’s Desire, which had just displaced Abba.

It was decided then that the band should go back into Alberts to cut another album, not knowing how long it might be before they got another opportunity to record. “In those days,” said Michael Browning, “you didn’t take two years between records. It was nothing to record two or three in a year.”

The band’s rapidly rising star was acknowledged when they arrived in Sydney in February and checked into the Sebel Town House, the five-star hotel still chosen by visiting rock royalty.

HELEN CARTER: “I was with Bon the day he got a $500 royalty check. They were staying at the Sebel, so obviously by then they were making a bit of money, but this was the first royalty check he’d got which was substantial, and he was just like, Look at this! His face lit up, he was just really happy at being paid for something he loved doing.

“He was of the old school, where rock’n’roll was everything. To him, it was still rebellion. I mean, it wasn’t like he was a guy who was saying, Oh, I’ve been doing gigs for years now, how come I haven’t got any money? That didn’t come into it. He was an innocent, I suppose.

“By that stage, everywhere you went there’d be women hanging around, in the hotel foyer, outside the venue, or the dressing room. So Bon would say, Here’s the key to the hotel room, I’ll be up in half an hour; because he had to deal with not just women but fans. And he really felt he had an obligation to hang around and talk to them.”

The band cut Dirty Deeds Done Dirt Cheap during February. So quickly after TNT, they had virtually nothing up their sleeves.

MARK EVANS: “Angus came up with the title. I remember when I heard it, I thought it sounded familiar, and ten years later I worked it out—it’s some cartoon character, off Beanie and Cecil, the villain, Captain Pugwash, he used to say that.”

HELEN: “Bon would play demos of music he had to write to. He’d just sit around the hotel room and have it going in the background, formulating ideas. He always had a cassette player, and at the time, his favorite song was “Love To Love You, Baby”, by Donna Summer. Which shows another side to him, musically.”

Bon still sought a lot outside the band.

HELEN: “Angus is pretty straightforward. Bon was almost an intellectual in comparison. The only way he could gauge anything, or write about anything, was to talk about other stuff, and we did a lot of talking. It wasn’t like we went back to his room, had sex for 12 hours and that was that. To be quite honest, I don’t think, say, talking to the road crew or whatever would have been terribly stimulating to him.”

But of course, Bon could mix it with anyone. And if women weren’t present, at least not ladies—as distinct from those with whom your secret was safe—then Bon could be a very bad boy. Bon’s mythic persona was further fuelled by the subsequent publication of a feature story in the Australian edition of Rolling Stone, which opened on Bon vomiting after a show, the victim, apparently, of a “bad bottle of Scotch,” whatever that means. In reality, his drinking was fair to middling. Anthony O’Grady witnessed the same episode, as the band played a few final gigs in Sydney whilst recording the album, and he reported in RAM: “[Bon] sometimes gets the same look that battle-scarred alley fighters have—a look of indifferent bloodlust. Kick ’em in the teeth and they’ll just spit blood and get up again.”

At the same time, O’Grady remembers that at the end of that night, back at Burwood, Bon and he were ushered outside to wait in the car when George wanted to “talk business” with his brothers, and Bon happily acquiesced, proceeding to simply pass out in the back seat.

HELEN: “I know that when you get a bit successful, because the pressure and everything else increases, you do drink too much. Especially if you’ve just done a fantastic show or something, you come off stage and you want to . . . But it didn’t rule his life. It was part of his life, but it wasn’t the major feature. The major feature was purely and simply getting up on stage and doing it, he just loved that.

“He used to gargle with Coonawarra red [wine] and honey, every morning. This is giving away trade secrets. But that was the secret to his great voice.”

Dirty Deeds was rushed; but then, everything was a rush for AC/DC at that time. With the UK release of the High Voltage album (which was in fact a compilation of tracks from the Australian albums High Voltage and TNT) now scheduled for May, and a UK tour supporting Paul Kossoff’s Back Street Crawler locked in for April, the flight to London was finally booked—for April Fool’s Day.

When they finished recording it, Dirty Deeds was put into cold storage. It had turned out as an equally inconsistent echo of its predecessor. The title track was more sloganeering; “Big Balls” is pure vaudeville double entendre; and “There’s Gonna Be Some Rockin’” and “RIP (Rock in Peace)” are pretty much the same song, both mindless chugalug boogies. “Squealer” was an inferior sequel to “Rocker.”

The remaining four tracks save the album. “Problem Child” fittingly became a staple of the band’s live set, a crunching, threatening flurry. “Ain’t No Fun (Waiting Around To Be a Millionaire)” is a boogie elevated by a superior lyric and greater extension on the band’s part.

But it was the album’s closing two tracks, “Ride On” and “Jailbreak,” that were its killers, a double-punch equal to that which opened TNT. “Ride On,” despite borrowing the chords from ZZ Top’s “Jesus Just Left Chicago,” is a statement of Bon’s tomorrow-never-comes credo whose poignancy has acquired a rueful dimension since his death. It segues abruptly but perfectly into “Jailbreak,” a virtual manifesto for AC/DC—relentlessly thudding release.

In March, as the track “TNT” was released as a single, the band flew to Melbourne to attend a gold record reception and formal farewell party. Three plaques each for High Voltage and TNT were presented. The band regrouped in Sydney to play one final show at the Lifesaver before they left (it was at this show that Angus stripped for the first time, flashing his bare behind, a routine that features in AC/DC’s shows to this day). The night before flying out, a celebration was thrown at Burwood for Angus’s nineteenth birthday.

HELEN: “It was a very quiet affair, just a couple of pizzas and a Billy Connolly record. Bon was excited, but skeptical about it [going overseas]. You know, being 30, not that that’s old, but in terms of starting a career, internationally, in an industry in which at that stage, if you were an Australian band, you may as well not have existed.”

As “TNT” climbed the Australian charts, eventually peaking at number eleven, Michael Browning played down the band’s departure. He’d been through it all before. “I’ve seen too many Australian groups say, Oh yeah, we’re going over to England and we’ll be big, and when it doesn’t happen straight away, no one in Australia wants to know about them anymore,” he told RAM. “AC/DC are an Australian group and we don’t want to spoil anything we’ve built up here.” Maybe he was just trying to cover his arse.

The band couldn’t have cared less. As Angus told Record Mirror & Disc shortly after arriving in England, “Success there [in Australia] means nothing. We left on a peak rather than overstaying our welcome, and set out to plunder and pillage.”

Spencer Jones, whose own band the Beasts of Bourbon would later cover “Ride On,” remembers seeing that last show they played. “It changed my life. There was this girl there, and she got up on stage and started to do a strip. She was quite a big girl, and she was just dancing around without any clothes on. So Bon picked her up. He just put one hand around her neck, and one on her crotch, and he just raised her above his head and stood there with her aloft like that. It was the most macho, sexist pose imaginable, but Bon could get away with things like that.

“And while all this was going on, Angus was up on someone’s shoulders, and he was trying to get to the bar, this long bar they had at the Lifesaver. The place was packed, you couldn’t move, but somehow they punched their way through, the people sort of parted like the Dead Sea. Angus hopped off at the bar and he did the duck-walk. Meanwhile, Bon’s just standing there with this girl on his shoulders. It was incredible. And then when Bon let her down, the roadies came on to help her, but they didn’t just throw her back into the audience, she was ushered backstage.”

HELEN: “No one else could get away with that stuff. I think that was what Bon actually loved about doing what he was doing, he really could, if he wanted, do anything he wanted. And he loved that. He loved that freedom.”