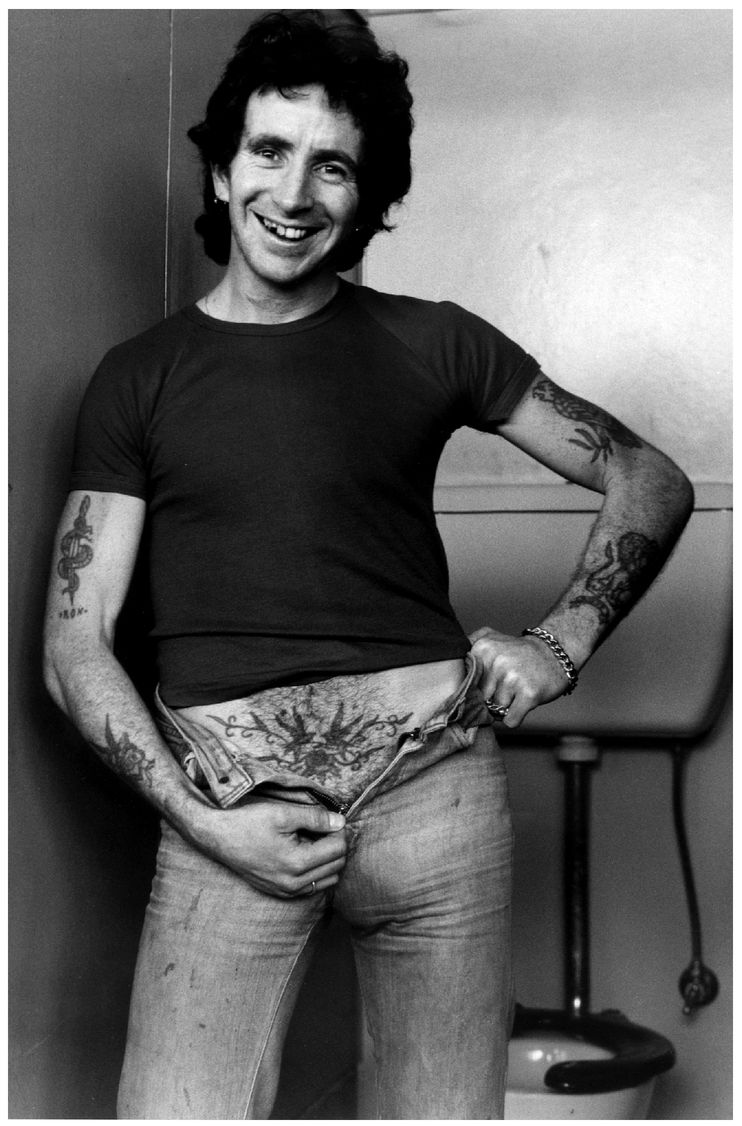

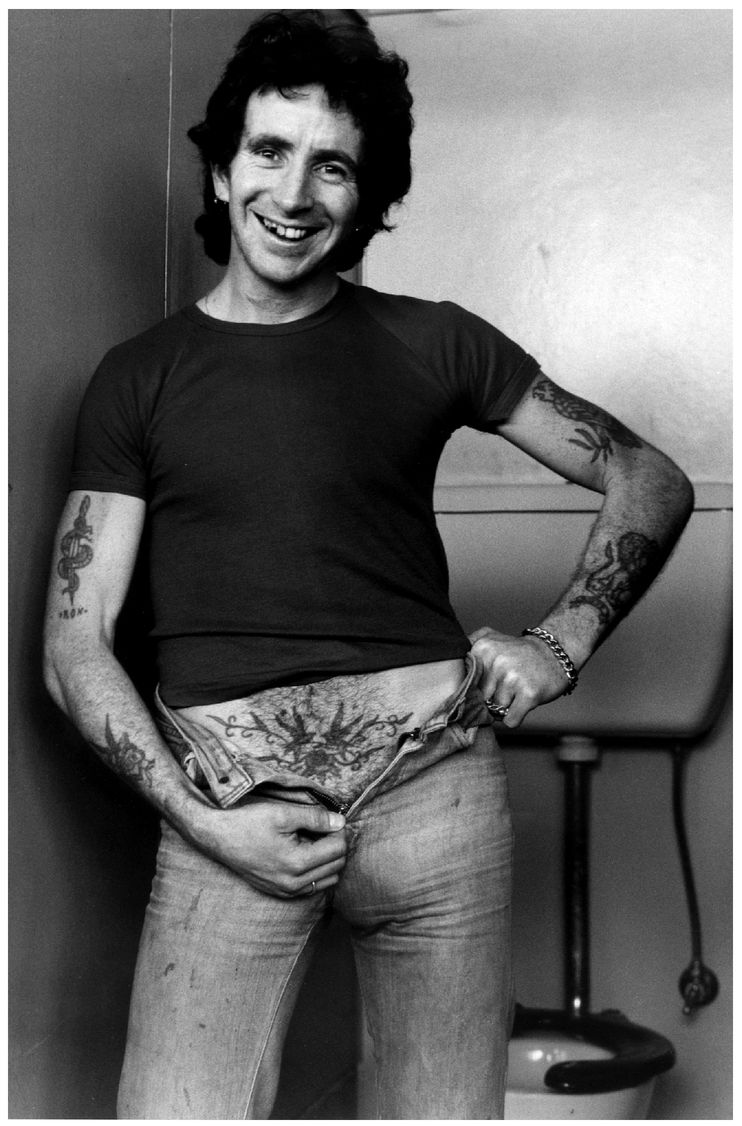

(Graeme Webber/Australian Rock Folio)

INTRODUCTION

When Bon Scott died in London in February 1980, AC/DC was on the verge of the breakthrough that established them as one of the most popular rock’n’roll bands of all time.

AC/DC was then still a new band on the world stage, as the schoolboy get-up of spotty young guitarist Angus Young emphasized. But Bon himself was a veteran, the self-confessed old man of the band, a 33-year-old who had already been around the block twice since the sixties. When he was pronounced dead on arrival at Kings College Hospital, the cumulative grind of nearly 20 years on the road had finally caught up with him.

Bon Scott was a man who lived for the moment. And when those moments had run out, his reputation solidified into legend—this was indeed one of the last true wild men of rock. The graffiti BON LIVES! is still to be found scrawled on walls all over the world.

Dead rock stars are often deified on the basis of martyrdom alone, however senseless. But Bon Scott was a working-class hero in life, and he became an icon in death.

AC/DC carried on after Bon died—as he would certainly have wanted them to—but while the later line-up of the band, with singer Brian Johnson, has enjoyed the greatest success, it is impossible to shake the feeling that it ain’t what it used to be. The Young brothers, Malcolm and Angus, who formed AC/DC and still run it, have acknowledged it was Bon who set them on their path, and the band today has only a faint echo of the earthiness, humor and honesty he invested it with.

AC/DC’s back catalogue has never been out of print, and is still selling. In 2003, when the band was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in the US, AC/DC could claim worldwide album sales of over 120 million, making them the fifth-biggest rock act of all time behind only the Beatles, Led Zeppelin, Pink Floyd and the Eagles (and ahead of the Stones, the Bee Gees, everyone). “I’ll go on record as saying they’re the greatest rock’n’roll band of all time,” says Rick Rubin, arguably the most important record producer of the last two decades, and a man who measures all his work against one album—Bon’s swan song, Highway to Hell.

By 2005, by which time streets had been named after AC/DC in Madrid and Melbourne alike, and Bon’s grave in Fremantle was listed as a heritage site by the National Trust following the 25th anniversary of his death, AC/DC’s influence was so pervasive that new Australian band Airborne incited an international bidding war on the basis that they sounded more like AC/DC than all the other young “new rock” bands trying to sound like AC/DC. Like Bon-era AC/DC, of course.

But beyond the shiny garlands and concrete monuments, beyond his musical legacy, beyond even the timeless appeal he exerts on successive generations, Bon has an iconic status which is intangible, a given in our popular cultural heritage. As an Australian musical icon, he has a wider appeal than Dame Nellie Melba, Johnny O’Keefe, Nick Cave, even Slim Dusty. Appellations like “an Australian Jim Morrison” are simply degrading—Bon is the world’s one and only Bon and nothing less.

Bon embodies the tearaway spirit, and no one he’s touched—even though they may “grow up” and leave rock’n’roll behind, shear their greasy locks and trade their denim jacket for coveralls or a shirt and tie—will ever forget his example, the mischievous glint in his eye and the screeching call to arms.

Bon’s image was not so emblematic that he might now be mass produced like a Ned Kelly or a Kiss or Elvis doll, or even an Angus Young doll; nor does he exist in the Australian collective memory as faded black-and-white newsreel footage, like, say, that of cricket legend Donald Bradman cutting an English field to pieces. Nor is he a still photograph, even for all the forceful motion it might capture—as so many indelible images of Elvis do. No, we are more likely to remember Bon fleetingly, flashlike, mercurial. He will be performing, on TV’s Countdown maybe, or at a show you went to but can’t fully remember after all those years and the rush and haze it was at the time anyway. He will be a splay of elbows and skin and tattoos, grinning with evil intent, grabbing at the microphone, screeching in his inimitable fashion, the center of a driving storm of volume, rhythm and blues that enveloped everything, that simply lodged itself in the atmosphere as part of the air you breathed and so to which reaction was involuntary, the body jerking in tandem motion. This was rebellion and release superior to any other available in spiritually bereft suburbia. And Bon was its advocate, a denim-clad Pied Piper with a bottle in his hand, a lady in waiting and the hellhounds on his trail . . .

Bon updated the Australian larrikin archetype. He was “the original currency lad,” as Sidney J. Baker defined him in The Australian Language: “tough, defiant, reckless,” plugged into the urban, electric twentieth century. Part of Bon’s appeal was vicarious, as it always is with rock stars—they live out our fantasies for us, and Bon very much lived the life of excess his audience could only dream about. But his immortality is not the result of nostalgic yearning. Even after his death Bon remains potent, the brute poet of the inarticulate underclass, a spokesman for not a generation but a class, a class with little influence or barely even so much as a voice. In railing against conformity, mediocrity and hypocrisy, Bon’s rebellion was blessedly not nihilistic, however, but rather the opposite—it expressed a lust for life that knew no bounds. With a disregard for all the niceties—even though, ironically, an impeccable politeness was one of Bon’s endearing personal traits—he might have been saying nothing more than, Believe nothing they tell you! Break free! Find out for yourself! Live life!

Bon regarded AC/DC’s 1976 hit single “Jailbreak” as one of his best songs, and indeed it might well stand as his most succinct autobiographical statement—jail being a blunt metaphor for the straight life.

It’s true that Bon himself grew up hard, even served time, but he had no chip on his shoulder. Nor was he motivated by the short man’s syndrome that seems, at least in part, to drive an Iggy Pop or a James Brown. Like Elvis, Bon loved and respected his parents; it was just that he rejected their way of life, as he saw it, the slow quiet suburban death of stolid conformity and insincere gestures. No gesture was ever so sincere as the finger Bon gave to all of this—to polite society, the silent majority, which, with its blinkeredness and apathy, was to Bon the antithesis of what life was all about.

Bon surmounted the odds to become a rock’n’roll star, a singer and songwriter. He wasn’t so much a singer as he was a screamer. He could play drums, as he did with his father in the Fremantle Pipe Band. But leaving school at 15, he hardly had any grand plans. It would probably have been enough that he stayed out of trouble. It is testimony to Bon’s strength of character, his pure desire, that after his stint behind bars he never went back there.

Bon Scott was the personification of the old adage, “It’s the singer, not the song.” He was never more at home than on stage, and perhaps more than his abilities as a singer and songwriter, he was great as a performer. His brilliance was that you believed in him; that, as they say, he could sell a song. Maybe it was his refusal to take anything, himself especially, too seriously—maybe it was just his impishness—but there was something conspiratorial in his grin that encouraged people who might otherwise never have stepped out of line to join with him in giving the finger to everything dull and constraining.

Something touched a nerve, made a connection. Journalist George Frazier, on the occasion of Janis Joplin’s death in 1970, wrote a eulogy to her in the Boston Globe which uncannily evokes Bon: “. . . an unkempt, vulgar, obscene girl (though never malicious and with a certain sweetness) who, given a microphone and an audience of her peers, became a wild child. She really couldn’t sing very well and she was far more gamin than graceful, and yet the young, as is their way these days, responded to her because of her shortcomings, because of her desecration of discipline. She was marvelous because she was so dreadful, so much animal energy and so little art.”

That Bon too was, and still is, reviled almost as equally as he’s adored only confirms his potency. There is perhaps a little bit of Bon in everyone, only some people don’t want to admit it—people who don’t like getting their hands dirty.

Bon’s old friends like to say his life was a success story because, it would appear, he got exactly what he wanted. He was initially driven not so much by the need to express himself as the desire, simply, to become a rock’n’roll star, to escape that monstrous suburban straitjacket—and he achieved precisely that.

Vince Lovegrove, who was co-vocalist with Bon in the Valentines in the sixties, wrote in an obituary to his old friend: “To Bon, success meant one thing—more—more booze, more women, more dope, more energy, more rock’n’roll . . . more life!”

They say that being in a rock’n’roll band is a sure way of prolonging adolescence, of putting off growing up—and it is. But by the time AC/DC started to become really successful, Bon had been around for so long that the success only served to illustrate to him what was really important. Fame and riches, in themselves, are empty. The tragedy of Bon’s death—along with the fact that in so many ways he died alone in the world—was that he was only just starting to come to terms with a life that had to be lived—which he found he needed to live—beyond rock’n’roll. Off the road. He had always been so busy chasing his dream that he never stopped running. His only refuge was in alcohol and sex. When late in the piece he did find the space and time to glance over his shoulder, or stop at a byway and look at his life, at life in general, he realized what he was missing: a home. It doesn’t matter who you are, you need a home to go to.

Bon was a wild man of rock, it’s true; but the Bon Scott behind the image was a different person, as is so often the case.

“I encountered Bon Scott a number of times during the seventies,” wrote Australian Rock Brain of the Universe Glenn A. Baker, “and each meeting served to increase my incredulity that a performer’s public image could be so at odds with his real personality. Bon really was a sweet man. He was warm, friendly and uncommonly funny. He did not breathe fire, pluck wings off flies or eat children whole. And while his daunting stage persona was by no means fraudulent, it was most certainly a professional cloak that could be worn at convenient moments.’

Nobody who knew Bon can find a bad word for him. He had great generosity of spirit, perhaps too much. But while he was a consummate professional, as everyone who worked with him testifies, he always leaned heavily on the bottle. The monotony of life on the road ensured it was so. Alcoholic death crept up on him.

Being in a rock’n’roll band is also akin to being adopted by a surrogate family, and to Bon “the band”—whichever band he happened to be in at any given time, from the Valentines in the sixties, through Fraternity in the early seventies, to AC/DC—was always the closest thing he had to a home.

Bon got married during the heady early seventies. But just as the hippie dream went up in smoke, Bon’s marriage too fell apart. Bon was torn during those days, to a point where, literally, he almost killed himself. It was only AC/DC that saved him.

AC/DC provided Bon with a new purpose, a new family. With Malcolm and Angus’ big brother, former Easybeat George, presiding over AC/DC from his studio lair, the Youngs were a tightly-knit Scots clan that worked on an all-or-nothing, us-against-them basis: Bon, who had the talent they needed, and happily also happened to be a Scot, was accepted as one of them, a blood brother, and that was that.

Bon, however, was a quite different type of person to any of the Youngs. He was outgoing, good-humored, and trusting, while the Youngs were a closed shop, uniformly suspicious, almost paranoid, possessed of the virtual opposite of Bon’s generosity of spirit, and prone to sullenness. Just as nobody can find a bad word for Bon, few people who have had dealings with the Youngs can find a good word for them. But Bon was united with Malcolm, Angus and George because they let him in, as they did so few others, and they shared a common goal—the music—and if nothing else, a ribald sense of humor.

Gradually, though, as the band became more successful and the mood within it more businesslike (if not downright venal), and as everyone cultivated their own individual personal lives, Bon found himself more alone than ever. In the end, he really did have nowhere to go.

The other tragedy in Bon’s death was not so much that he didn’t live to make it (Highway to Hell, his last album with the band, was big enough, and after a certain point the magnitude of success becomes academic); it was rather that as a writer, he was only just hitting his stride.

AC/DC never received their critical due during Bon’s lifetime. Bon was contemptuous of the critics who didn’t even try to understand AC/DC; nevertheless, while there are few artists who don’t crave success on both critical and commercial fronts, what was most important and satisfying to Bon was that people simply “got off on it.”

But if it’s true, as Matisse contended, that an artist’s greatness is measured by the number of new signs he introduces to the language, there’s no doubt that AC/DC are one of the great rock’n’roll bands.

There’s something about listening to old AC/DC albums now, as if, even with all the vitality they still exude, they’re preserved in amber. At the time the band was making those records, however, there was nothing else that sounded like them; that so much sounds like them now is testimony to their greatness.

The crosscut riffing which soon became AC/DC’s trademark—due to the telepathic communication between the two guitarist brothers, the Gibson and the Gretsch—had a seminal influence on rock as it lurched into the eighties. AC/DC laid the blueprint for what would become known as stadium rock—but also for its official antithesis, the grunge of the ’90s (not to mention contemporary “new rock”). The grunge-metal axis which revitalized rock in the nineties owed as much to AC/DC as it did to Led Zeppelin, the Stooges, the New York Dolls, the Velvet Underground, the Sex Pistols, Neil Young, the Ramones and Black Sabbath. Kurt Cobain, after all, taught himself guitar by playing along with AC/DC records.

Critics were slow to acknowledge all this. It’s ironic though perhaps understandable, that Brian Johnson, as an outsider who joined AC/DC at a time when they were a fully realized band, has become their one spokesman capable of self-analysis. As he told RAM in 1981, “. . . with AC/DC it’s so easy and simple, critics can’t get into it and therefore they can’t describe it.” He’s saying that AC/DC have none of the identifiable elements that critics like to latch onto, whether they be literary—lyrics that beg to be analyzed—or the obvious signs of traditions inherited, sources updated.

The wordy Bob Dylan is the orthodox rock critic’s yardstick against which all else is measured. Dylan invested rock with meaning, made it something “serious” (like it’s not serious when Elvis declares, “You ain’t nothin’ but a hound dog,” and turns the entire Western world upside down!). But too many critics suffer from an inferiority complex in the face of their “high art” brethren who look down on rock’n’roll; they seem to think rock’n’roll needs elevation. What they fail to realize is that rock’n’roll was born of base instincts, of disposability and banality—the commercial imperative—and it’s still at its glorious best when it revels in these qualities, accepts them only to transcend them, becomes like the brilliant implosion of a dark star which itself dies but burns an indelible mark on those who see it.

It is pretension, not intelligence or sensitivity, that is rock’n’roll’s worst enemy. A pretension that is ashamed of rock’s gutter origins.

Music, by definition, transcends the literal, and rock’n’roll is at its best when it springs purely from instinct, uncluttered by intellect. Simple and direct, it can have an immediate power that doesn’t have to preclude resonance. If Bon fails to fit the orthodox Dylanesque measure of a great rock lyricist, then more power to him. The real point is a matter of attitude, tone, and honesty. Bon was a storyteller who had a terrific eye for detail yet liked to get straight to the moral of the story, and who also, importantly, rejected self-censorship (he was aware, for instance, of the inflammatory nature of a song like “She’s Got the Jack” even when he wrote it, but he still went ahead with it).

In a way, AC/DC never fitted in. Clearly, they’re not heavy metal, as they’re commonly described. Few heavy metal bands have a sense of humor, to start with. AC/DC developed in isolation, in Australia in the mid-seventies, citing only pure, classic fifties rock’n’roll as a source—Little Richard, Chuck Berry—and it’s perhaps because they sprang so directly from this untainted well that, whilst their sound might have seemed generic, it was actually because it was so original that it defied description.

Even Britain’s New Musical Express, AC/DC’s erstwhile critical archenemy, had to admit upon the release of Highway to Hell, “By taking all the unfashionable clichés and metaphors of heavy rock, discarding every ounce of the genre’s attendant flab, and fusing those ingredients with gall, simplicity and deceptive facility into a dynamic whole, they have created an aesthetic of their own.”

Says Rick Rubin: “When I was in junior high in 1979, my classmates all liked Led Zeppelin. But I loved AC/DC. When I’m producing a rock band, I try to create albums that sound as powerful as Highway to Hell. Whether it’s the Cult or the Red Hot Chili Peppers, I apply the same basic formula: Keep it sparse. Make the guitar parts more rhythmic. It sounds simple, but what AC/DC did is almost impossible to duplicate. A great band like Metallica could play an AC/DC song note for note, and they still wouldn’t capture the tension and release that drives the music. There’s nothing like it.”

There is something uniquely Australian about this. AC/DC’s down-to-earth, no-frills style—a sense of modesty almost, even in their arrogance; a passion more appropriate to amateurs, and a disdain for self-indulgence—coupled with a spirit of belligerent independence, a devout work ethic, and a profound sense of irreverence, has provided a model, one way or another, for practically every other Australian rock’n’roll act that has subsequently succeeded overseas, from INXS to Nick Cave to Silverchair to Jet.

Bon was color to the band’s movement. As such, as a rock’n’roll star, he was granted license to exercise a total lack of restraint, in both his life and art. His fans admired him because he wasn’t afraid of anything; it seemed that he never stopped to think, just leapt straight in—he gave. He drew his art from life, the rampant fornicator stripped bare. The classic bluesmen addressed many of the same issues, only with more finesse—as does a contemporary black artist like Prince—but Bon, free of all artifice and pretension, talked plain to such a point that it went under the heads of many.

But even if Bon might have had better writing ahead of him, that he still left us with such classics as “High Voltage,” “Long Way to the Top,” “Jailbreak,” “Live Wire,” “She’s Got Balls,” “Ride On,” “Let There Be Rock,” “Whole Lotta Rosie” and “Highway to Hell,” is enough. Certainly, AC/DC has produced little of equal stature since; to this day, the guts of their live set derives from their first six years with Bon.

By 1979, AC/DC was an altogether different entity to what it once was. Torn by ambition, paranoia and betrayal, the band had become big business. Bon’s de facto family had left home. Both Malcolm and Angus were buying houses and had girlfriends, whom they would eventually marry. Bon meanwhile, on a return trip to Australia, bought a motorcycle. With customary bravado, he joked that he wasn’t ready yet to settle down. But in reality, unimpressed by all the glittery excess and phoniness of stardom, and, if nothing else, just plain tired—or maybe, just finally starting to become a little jaded—he was determinedly trying to remain in touch with his roots, with the old friends he had who he knew were true friends. That he lacked the soul mate he so desired ate away at him. The bottle, and rock’n’roll—always the music—was all that sustained him meantime. He was working on new material for an album he knew would be as huge as Back in Black turned out. He was excited at the prospects. But then, suddenly, surprisingly, his life, his body, demanded its own back.

For too long, Bon had pushed himself too hard. He could give no more.

“The trouble with eulogizing a Janis Joplin,” concluded George Frazier, “is that, in doing so, we are eulogizing not achievement or artistry but a lifestyle that did no one any good, neither her nor those who idolized her. To try to pass off as art what was merely drunk and disorderly is to mislead the young. There are times when to speak ill of the dead is not to do a disservice, but to endow a wastrel existence with a certain significance—a cautionary memento mori to would-be disciples. In other words, what comfort is Southern Comfort when it contributes to the early end of a foolish little girl? Sometimes the young are very stupid.”

“Jailbreak” became a self-fulfilling prophecy. Like the song’s hero, Bon broke his shackles—but only to be shot down in flight.