THE RIGHT REVEREND SAMUEL SEABURY CALLED ALEXANDER AND OTHER PATRIOTS “SCORPIONS.”

AFTER A HESITANT START, Alexander found his voice. He condemned the British for closing Boston’s port after the tea protest. He urged his fellow colonists to protest the unjust taxes. He called for a boycott of British goods, something that would make the colonists suffer, but would cause even more pain to the British.

His ideas and his energetic delivery lit up the crowd. No one could believe someone so young could be so persuasive, so passionate, so informed.

A murmur rose: “It is a collegian! It is a collegian!”

His time as a student was coming to an end, and his career as a revolutionary was beginning. He would bridge the transition from student to soldier with words, taking on the loyalists’ own Westchester Farmer in a series of fiery essays.

The Farmer was the Reverend Samuel Seabury, a well-known loyalist who took vicious aim at the Continental Congress in anonymous pamphlets. The Farmer riled the patriots so much that they dunked copies in tar and feathers and tacked them to whipping posts. Perhaps because Seabury was a friend of Myles Cooper, the president of Alexander’s college, and perhaps because he did not yet think of himself as a full-fledged American, Alexander wrote anonymously as “A Friend to America.”

THE RIGHT REVEREND SAMUEL SEABURY CALLED ALEXANDER AND OTHER PATRIOTS “SCORPIONS.”

A month after the first Farmer pamphlet appeared, he responded with a powerhouse thirty-five-page pamphlet. He wrote stirringly about freedom and slavery, and the God-given, natural right the colonists had to liberty. He’d seen firsthand how enslaved people suffered. He’d seen how courts could abuse the powerless. This would not stand.

“The only distinction between freedom and slavery consists in this: In the former state, a man is governed by the laws to which he has given his consent… . In the latter, he is governed by the will of another… . No man in his senses can hesitate in choosing to be free, rather than a slave.”

The Farmer didn’t intimidate Alexander. When Seabury called the patriots “scorpions” who would “sting us to death,” Alexander fired back, intimating Seabury’s critical abilities were so lousy that he preferred the man’s disapproval to his applause.

Even so, Alexander wasn’t yet arguing for revolution. He wanted Parliament to stop imposing taxes without the colonists’ consent. One argument justifying this was that Parliament and the Crown were separate entities. The colonists could be subjects of the king but not subject to Parliament’s laws. Impressed readers wondered who this Friend to America was. There were rumors that the author was Alexander, but people didn’t believe someone so young could know so much about politics, language, and human nature.

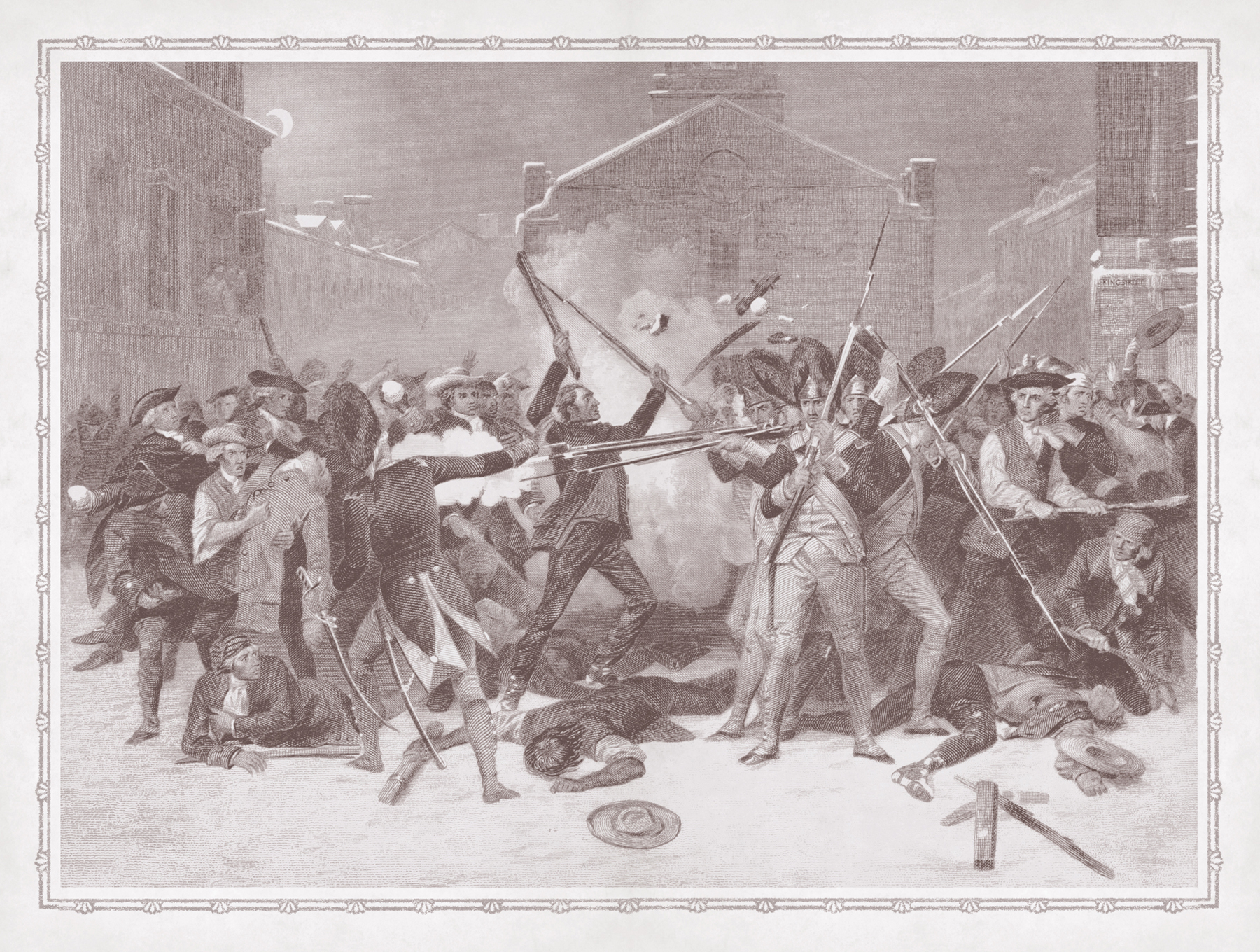

Bloodshed could not be averted by words, though. Blood had already fallen in 1770 at a massacre in Boston, where British soldiers killed five men, including Crispus Attucks, the son of enslaved people—one African and one Wampanoag Indian. More was shed on April 19, 1775, when British soldiers quartered in Boston headed to Lexington to seize patriot leaders Samuel Adams and John Hancock, along with weapons and ammunition the colonists had stockpiled in Concord.

NEWS OF THE 1775 BOSTON MASSACRE REACHED NEW YORK CITY FOUR DAYS LATER. ALEXANDER AND HIS CLASSMATES TOOK UP ARMS.

Colonial minutemen—volunteers willing to serve on short notice—had been tipped off. Someone opened fire in Lexington, and eight colonists died when the British blasted back. Two more were slain in Concord, but as the British retreated, the tables turned. Patriots fired from hiding spots along the way, killing or wounding 273, far more than the ninety-five casualties on the colonists’ side.

FOUR DAYS LATER, NEWS OF THE VIOLENCE REACHED NEW YORK CITY.

Four days later, news of the violence reached New York City. The Sons of Liberty leapt into action. They seized supplies on British ships headed to Boston, as well as a cache of weapons held at City Hall—more than a thousand muskets, bayonets, and boxes of ammunition. These were used to arm outraged New Yorkers, including Alexander and his classmates.

Alexander immediately went to work practicing military drills. Every day, he and his classmates put on caps that read LIBERTY OR DEATH, along with short, close-fitting green military jackets. They marched through the churchyard of St. George’s Chapel, practicing under the sharp eye of a former member of a British regiment.

Alexander drilled like a man possessed. Guns. Explosives. Maneuvers. Order. As relentlessly as he’d studied academics, he mastered the art of war, and not just the maneuvers, but the mindset.

And it was just in time. The patriots’ rage in New York was percolating into violence.

On April 24, eight thousand furious men gathered outside City Hall. The next day, an anonymous handbill blamed five Tories, including Hamilton’s professor Myles Cooper, for the deaths of the patriots in Massachusetts. On May 10, after a protest, a drunk and angry mob stormed King’s College. The rabble knocked down the college gate and rushed the steps to Cooper’s apartment. As the mob approached, Alexander stood his ground and launched into a speech, arguing that harming Cooper would sully the cause of liberty. In doing so, he bought his professor time to escape.

Even though he disagreed with Cooper politically, Alexander was more than willing to stand as a human shield when it was the right thing to do. He could have been beaten to death. He could have lost his stature as the young voice of the Revolution. But none of that mattered to him as much as human decency.

The two men never saw each other again. But Alexander, filled with courage and scenting war on the horizon, had set an important standard for himself. His life mattered less than his principles. He was above the witless rage of a mob. He was a man of honor.

AMERICAN TROOPS WERE INITIALLY OUTMATCHED BY THE BRITISH, THOUGH THEY TOOK POSSESSION OF BREED’S HILL ON JUNE 16, 1775.

THE SECOND CONTINENTAL CONGRESS APPOINTED George Washington on June 15, 1775, to lead the Continental Army. The challenge of this loomed large. The colonists were in no way ready. Alexander’s friend Elias Boudinot was with Washington when the general learned they had enough gunpowder for only eight rounds a man, and they had fourteen miles of line to guard. Washington, never much of a talker, could not speak for thirty minutes.

Not long afterward, a 158-foot Royal British Navy man-of-war called the Asia dropped anchor in New York Harbor. She had three huge masts and sixty-four guns. The firepower she represented was terrifying. Inch for inch, she had the most guns of any ship the Royal Navy had yet built. The Asia could burn down the city.

Washington had to take the Hoboken ferry into the city to avoid her guns. On June 25, Alexander got his first glimpse of the forty-three-year-old general as he traveled down Broadway in a carriage pulled by white horses. Washington was tall and fit, about six foot two, and he cut a deliberately impressive figure. When he’d served during the French and Indian War, he complained about the sad state of his regiment’s uniforms, with their thin fabric and sorry waistcoats. Conscious that leadership required a certain look and bearing, Washington dressed himself in tall black boots, buff-colored wool breeches with a matching waistcoat, and a blue coat with shiny buttons and a purple sash, along with a curved sword of grooved steel.

GENERAL GEORGE WASHINGTON TOOK COMMAND OF THE CONTINENTAL ARMY ON JUNE 15, 1775.

HIS MAJESTY KING GEORGE III IGNORED AN OLIVE BRANCH FROM THE SECOND CONTINENTAL CONGRESS.

The next week, Alexander and the rest of the citizens of New York were on edge. The sultry heat of summer hung around the city like a blanket. The Second Continental Congress authorized an Olive Branch Petition on July 5 to send to King George. The king ignored it and, on August 23, fired back a royal proclamation of his own.

His American subjects were in open rebellion. His military would break it.

Hours later—even before word of the proclamation made its way across the Atlantic—the Asia opened fire from the East River.

The Americans had no warships to fire back, which meant Manhattan was vulnerable. An abandoned British military fortification—Fort George—was armed with two dozen cannons. The New York militia needed them. Alexander, along with Hercules Mulligan and fifteen other volunteers from his college, helped steal those weapons and bring them to the liberty pole. The men lashed ropes to the cannons, which weighed one ton each and were mounted on tiny wheels, and they dragged at least ten of them to safety before a barge from the Asia took aim at them. Under fire, the men pressed on, even as the rope blistered their hands.

UNDER FIRE, THE MEN PRESSED ON.

In a desperate moment, Alexander gave Hercules his musket to hold. He moved a cannon and asked Mulligan for his weapon back. Hercules, distracted by gunfire, had left the gun by the Battery. Undaunted by grapeshot and cannonballs screaming through the air, Alexander ran back and retrieved his weapon.

That night, a Sons of Liberty meeting place called the Fraunces Tavern was hit—a cannonball tore a huge hole in the ceiling. Fires blazed in the harbor, and their reflected flames lit up the windows. Alexander remained cool and focused even as terrified citizens panicked in the streets. He and the others managed to steal all but three of the Battery’s twenty-four guns, which they stashed under guard at the liberty pole.

Not long afterward, he wrote a letter about the mission and sent it to Hugh Knox, who printed it in the Royal Danish American Gazette. “I was born to die and my reason and conscience tell me it is impossible to die in a better or more important cause.”

His courage and drive made him a standout soldier, noticed by many. Elias Boudinot wanted Alexander to be an aide-de-camp to a brigadier general in the Continental Army, William Alexander, known as Lord Stirling. Other generals had noticed his talent, too.

Alexander hesitated. He didn’t want a desk job. He wanted to fight for glory on the battlefield. When the New York Provincial Congress ordered the colony to put together an artillery company, Alexander decided running it was the post for him. He turned the generals down, persuaded key people to back him, studied everything he could about artillery, and in March 1776, at twenty-one years of age, became captain of the New York Provincial Company of Artillery.

ULTIMATELY, ALEXANDER HAD SIXTY-EIGHT men under his command, and he took scrupulous care of them, even using his Saint Croix scholarship money to buy some of their equipment, expecting to be paid back from their future wages. He dressed his men in buckskin breeches and deep blue, swallow-tailed coats with brass buttons and buff collars that had white shoulder belts running diagonally across their chests. They had three-cornered felt hats with cockades and hung their muskets from leather shoulder straps. Hercules made Alexander an even higher-quality uniform, with pants of white fabric (tough buckskin was for the men doing the physical labor).

HIS COURAGE AND DRIVE MADE HIM A STANDOUT SOLDIER.

Not all revolutionary soldiers had such smart uniforms—or any uniforms at all. But Alexander was a natural leader and organizer, and he knew such things were important. He kept track of food, clothing, pay, and disciplinary action in a small book. He faced his share of challenges with his men. Nine days after he officially took command, he had to give one soldier the boot for “being subject to fits.” Two days later, another got kicked out for “misbehavior.” The next month, he court-martialed four men for mutiny. Others were found guilty of desertion and punished with days of bread and water and even whipping. Many other leaders had trouble turning recruits into soldiers. Not Alexander. Through his drills and leadership, his men became known as a model of discipline and order.

He made sure his men earned equal pay for their efforts. The New York Provincial Congress was responsible for paying his troops. The Continental Congress—which funded the Continental Army—had raised pay for its troops, but New York’s militia hadn’t kept pace, threatening his men’s morale and willingness to fight. He wrote letters that secured equal pay and provisions. He also did his best to instill discipline and promotions alike. His name crossed Washington’s desk when Alexander ordered one of his men to be lashed for desertion. Washington, a strict disciplinarian, approved.

GENERAL SIR WILLIAM HOWE WAS THE BRITISH ARMY COMMANDER IN CHIEF.

There was periodic good news for the patriots. In March 1776, the Continental Army drove the British out of Boston. But on the whole, things looked grim. They’d even had to melt lead rooftops and windowsills to make more ammunition.

ADMIRAL RICHARD LORD HOWE, WILLIAM HOWE’S BROTHER, COMMANDED THE BRITISH NAVY. TOGETHER, THE BROTHERS LED THE LARGEST MILITARY FORCE SINCE THE ROMAN EMPIRE.

They needed more than bullets. They needed warm bodies. Here, the British had a huge advantage. Starting in June, the massive British war fleet began to arrive in New York Harbor. Led by two brothers, General William Howe and Admiral Lord Richard Howe, the king’s fighting force comprised thirty battleships armed with twelve hundred cannons; thirty thousand soldiers; ten thousand sailors; and three hundred supply ships. It was the largest and strongest military since the days of the Roman Empire.

A COMMITTEE THAT INCLUDED THOMAS JEFFERSON AND JOHN ADAMS DRAFTED THE DECLARATION OF INDEPENDENCE. THE MEN BOTH DIED ON JULY 4, 1826, ON THE FIFTIETH ANNIVERSARY OF THE DOCUMENT.

The colonies had fewer than twenty thousand rookie soldiers. Many were old men. Boys in their midteens. Raw, disorderly, and sometimes even drunk. Discipline was an ongoing problem, as was basic hygiene. Though ammunition was in short supply, soldiers sometimes shot their guns to make noise and even start fires.

Nonetheless, the patriots forged ahead. On July 2, the Continental Congress voted to declare independence. (New York abstained.) It was a historic moment. No colony had yet broken away from its parent country and managed to set up a self-governing state. Even trying to do so was treason, which was punishable by death.

NONETHELESS, THE PATRIOTS FORGED AHEAD.

Hundreds of copies of the Declaration of Independence were printed and distributed. The document made its way to New York on July 9, and after it was read, a four-thousand-pound, gilded lead statue of George III astride his horse had its last stand in Bowling Green park. Patriots tore down the statue, cut it into pieces, melted the lead, and made 42,088 bullets intended for British bodies. (All but the head, which was rescued by loyalists and sent to England, where it disappeared.)

New York was difficult territory to defend, especially without a navy. But it was strategically important as a buffer protecting New England and as a corridor to Canada. Manhattan is long and thin, and the adjacent New York Harbor is deep enough to be filled with ships. Two rivers flanked the island, which was narrow enough for invaders to cross, trapping patriots between troops and ships.

The British made good use of this vulnerability.

On July 12, on a beautiful summer day, the British advanced. They sent the Phoenix, a forty-four-gun battleship, and the Rose, a twenty-eight-gun frigate, up the Hudson River. The wind and tide moved in their favor. Soldiers and panicked residents ran pell-mell through the streets, accompanied by the clamor of alarm guns.

A SOUTHWEST VIEW OF FORT GEORGE AND THE CITY OF NEW YORK.

Alexander, in charge of artillery at Fort George, opened fire on the enemy. The ships sent back cannonballs that crashed into houses and bounced down streets thick with terrified women and children. The American shots caused hardly any damage, but they filled the air with smoke and the stink of gunpowder as British ships slipped past.

Alexander commanded four of the biggest cannons. In the midst of fire, one of them burst. As many as six men died, and four or five more were wounded. Some of his men were drunk and failed to wipe the powder and quench the sparks from an earlier volley. Though he wasn’t to blame and wasn’t disciplined afterward, the ordeal devastated him.

At least his company had shown up. One soldier estimated half of the city’s artillerists were either drunk at bars or consorting with prostitutes instead of fighting. General Washington wasn’t pleased: “Unsoldierly Conduct must grieve every good officer, and give the enemy a mean opinion of the Army.”

IN THE MIDST OF FIRE, ONE OF THE CANNONS BURST.

The development boded ill for the Americans. The two warships made it past all the guns with hardly a scratch. There was no reason to believe the entire British fleet couldn’t do the same—trapping Washington and his men in New York.

Washington urged citizens to evacuate. Scouring the terrain from across the East River, Alexander didn’t think the Continental Army stood a chance against the British. He wanted to retreat—but a letter delivered by Hercules Mulligan received no response. Washington sent out general orders on August 8, indicating that his men were to be alert around the clock. “The Movements of the enemy and intelligence by Deserters, give the utmost reason to believe, that the great struggle, in which we are contending for everything dear to us and our posterity, is near at hand.”

A series of attacks began early on August 27. The British and their Hessian mercenaries crushed the American forces. The debacle dispirited Washington, who could only watch from afar through a telescope borrowed from King’s College. “Good God, what brave fellows I must lose,” he said. Lord Stirling, surrounded, bought time for fleeing troops before he was captured—which would have been Alexander’s fate had he chosen to work as the man’s aide.

The next afternoon, England’s General Howe ordered his men to dig trenches around the Americans, who were cornered in Brooklyn Heights up against the East River. After another day of attacks, Washington ordered an evacuation. Under cover of night, nine thousand Americans were rowed back to Manhattan. The sun rose before all the Americans had escaped, but a lucky fog rolled in, concealing the rest. George Washington was the last man to leave Brooklyn.

It was becoming increasingly clear to Washington that his army was a mess: soldiers who signed up for short-term engagements that they often abandoned; drunken men who took part in looting; Yankees who’d rather let their shirts rot on their backs than do the women’s work of washing them. Washington wanted a well-trained standing army—which would become a huge point of contention with some, but an issue on which he and Alexander were in perfect alignment.

“GOOD GOD, WHAT BRAVE FELLOWS I MUST LOSE.”

Weeks passed, and on September 15, five ships—including the Phoenix and the Rose—sailed up the East River and landed on the eastern shore of Manhattan at Kips Bay. They bombarded the colonists and unloaded barges full of British and Hessian troops, who aimed to keep the Americans trapped in the southern part of the island. Patriots—overwhelmed by the forces and their firepower—fled north.

Washington, enraged, ripped off his hat and threw it on the ground. “Are these the men with which I am to defend America?”

Alexander was one of the last to leave Fort Bunker Hill where troops had been stationed. He was flanked on the right by the enemy, blocking access to the rest of the army. Aaron Burr, an aide-de-camp to General Israel Putnam, arrived on horseback and urged the men to leave, else face capture or death. The men followed, and at one point Burr raced toward gunfire so that he could take on an enemy guard. Alexander arrived in Harlem Heights having lost a cannon and his baggage, but alive—thanks to Aaron Burr.

WEEKS PASSED WITHOUT FIGHTING AS THE troops made their way to White Plains. The battle there proved costly for both sides. The British lost more men, but the patriots were beginning to lose hope. On November 16, they lost Fort Washington, and thus the island of Manhattan. Four days later Fort Lee in New Jersey fell. A lesson was learned: no more open confrontations with the vastly superior British regulars.

By December, Alexander had become so sick he couldn’t get out of bed. His company was down to about thirty men. Some had died; others had deserted. Thomas Paine, who had been with the soldiers during the dispiriting loss in New York, captured the mood on December 19, during the darkest part of winter and the darkest moments of the early war:

“These are the times that try men’s souls. The summer soldier and the sunshine patriot will, in this crisis, shrink from the service of their country; but he that stands it now, deserves the love and thanks of man and woman.”

Alexander was no sunshine patriot. Sick as he was, he forced himself down to the Delaware River on Christmas night. It was so cold that ice caked the boats, which men poled across the ice-clogged Delaware. Snow and sleet fell on Alexander and his troops, who then marched eight miles dragging a massive artillery train with the aid of horses.

ALEXANDER HAD BECOME SO SICK HE COULDN’T GET OUT OF BED.

When they reached Trenton, they spied a miracle: the glint of metal off the helmets and bayonets of Hessians. Alexander’s men fired. The Hessians returned the favor. From behind, their footsteps muffled by falling snow, Washington and his men sneaked up on the Hessians as Alexander and his men blasted on, preventing the German mercenaries’ escape. A thousand enemy forces were captured that night, thanks in part to Alexander’s artillery company.

There was a second fight on January 2, and on January 3, Alexander led an attack on Nassau Hall at the College of New Jersey, the same school that had rejected his application. No one would reject Alexander now. A senior officer observed his arrival on campus: “I noticed a youth, a mere stripling, small, slender, almost delicate in frame, marching beside a piece of artillery, with a cocked hat pulled down over his eyes, apparently lost in thought, with his hand resting on the cannon, and every now and then patting it, as if it were a favorite horse or a pet plaything.”

The victories at Trenton and Princeton boosted the hearts of Alexander and his men. And then, on January 20, 1777, Hamilton received a note that should have thrilled him more than anything. It was from George Washington: an invitation to join his staff.

It wasn’t the moment Alexander had been waiting for, though. Glory on the battlefield—that was his dream. He hated the idea of shuffling papers instead of shooting guns. But he was still getting over his sickness, so he took the job.

Before long, he’d made himself invaluable to the general, who was quartered at the Arnold Tavern in Morristown, New Jersey. The tavern was a solid three-story building with two chimneys and a wide front porch. Washington and his men, including Alexander, spent about five months encamped in the area.

ALEXANDER HAMILTON LONGED FOR GLORY ON THE BATTLEFIELD, WHERE HE WAS A STANDOUT SOLDIER. HE IS DEPICTED HERE IN YORKTOWN, 1781.

As part of Washington’s staff, Alexander was brought inside the heart of the Revolution. He saw the challenges of managing a Continental Army alongside state militias, as well as the difficulties in fighting a larger, better-trained, better-funded, and better-equipped enemy.

Alexander was the gifted wordsmith Washington was not, and a huge part of his role was managing the correspondence that flooded his desk: letters from Congress and from the colonial legislators; orders that needed to be sent, most of which Alexander wrote; disputes between subordinates that needed management. He was the best of Washington’s writers.

PART OF A LETTER ALEXANDER SENT GEORGE WASHINGTON IN 1783. WASHINGTON’S FAITH IN ALEXANDER NEVER WAVERED.

There also were supply chains to manage, including munitions, clothing, food. This he’d learned to handle in Saint Croix. And there were people who needed attention: prisoners, and soldiers in need of promotion—again, something that put his shipping-clerk experience to good use. Alexander helped bring order to Washington’s staff, and thanks to his study and drilling, he also knew a great deal about political and military principles. Before long, he wasn’t just Washington’s right hand. Alexander was thinking and writing on Washington’s behalf, corresponding often with Congress and with leaders in New York. He also drilled troops and carried out vital missions.

After hours of writing and copying letters, sometimes as many as a hundred in a day, Alexander and the rest of Washington’s military family would sit around the dinner table and share stories each night. Quarters at the tavern were close. Washington’s aides often slept six to a room and two to a bed. (During the war, they even slept on the floor by the general’s bed when necessary—and that’s when they had shelter. Other times, they’d bed down under cover of trees and stars.)

ALEXANDER’S REGRETFUL REPLY WAS FLIRTY TO THE EXTREME.

Morristown did have one unexpected perk: Alexander had time to woo women, or at least try. Susanna Livingston, an old friend from Elizabethtown, inquired if she and a few friends might visit headquarters, and Alexander’s regretful reply was flirty to the extreme. He even described himself as “a valorous knight, destined to be their champion and deliverer.” He was so girl crazy, in fact, that Martha Washington named her randy tomcat after him.

ALEXANDER’S BEST FRIEND, JOHN LAURENS, WAS A FIERCE OPPONENT OF SLAVERY.

He made friends with the other aides and didn’t mind their calling him Ham or Hammie. One gave Alexander a nickname that stuck for life: the Little Lion.

Alexander was especially close with John Laurens, the strapping, intense-eyed son of a rich and powerful South Carolina politician. He and Laurens had much in common, an echo of Alexander’s friendship with Ned Stevens. Like Alexander, Laurens was interested in medicine. He too was a bold and sometimes even reckless soldier. And, despite being from a slave state, he hated the practice of enslaving human beings.

Another friend was one Marie-Joseph-Paul-Yves-Roch-Gilbert du Motier, better known as the Marquis de Lafayette. Given all those names to protect him in battle, Lafayette was a French aristocrat about Alexander’s age. He was so taken by the cause of liberty that he’d traveled to America with a ship and weapons he’d paid for himself. Like Alexander, Lafayette was an orphan. Together Lafayette, Laurens, and Alexander reminded people of the three musketeers from the Alexandre Dumas novel.

Older men in the military looked at Alexander as a source of hope. General Nathanael Greene, one of Washington’s most respected leaders, called Alexander “a bright gleam of sunshine, ever growing brighter as the general darkness thickened.”

ALEXANDER AND HIS MEN DOVE INTO THE CURRENT.

And the darkness did thicken. After a lull, the fighting returned. In July 1777, the British captured Fort Ticonderoga in upstate New York, and it felt as though victory had slipped forever out of reach. Alexander was at the front lines with Washington on September 11 for another brutal loss. The defeat at the Battle of Brandywine would lead to the British takeover of the new nation’s capital, Philadelphia, on September 26.

ALEXANDER WAS SENT TO THE SCHUYLKILL RIVER, WHERE HE DESTROYED FLOUR MILLS.

A week after this disappointment, Washington sent Alexander, Captain Henry Lee, and eight cavalrymen to destroy flour mills along the Schuylkill River before the British could use them. To make sure Alexander had an escape route, he planted a flat-bottomed boat on the edge of the river.

As he and his comrades were destroying the mills, a sentry fired a warning shot. The British were on their way. Captain Lee and half the men took off on horseback. Alexander and three others scurried for the boat. The British took aim. One of Alexander’s men was shot and killed. Another was wounded.

The river, swollen by recent rains, bashed furiously at the boat. The British fired away. Alexander and his men dove into the current. Lee watched the horror unfold. Alexander hadn’t surfaced, and Lee feared the worst. As soon as he could, the captain dashed off a letter to General Washington announcing awful news: the death of Alexander Hamilton.