FROM THE START, ALEXANDER threw himself into fatherhood with the same ardor and discipline he’d shown as a student and soldier. After seven months of close study, he had come to an opinion about his baby.

Philip was perfect. Well, nearly so. He was a bright-eyed looker. Good at sitting. Already, he was smart and an excellent babbler, who waved his tiny hand like a seasoned orator. His flaws were slight. He had chubby thighs, which might portend awkward dancing. Also, he tended to laugh too much.

Part of Alexander wanted only to bask in the glow of love for his wife and boy. His sad childhood still caused him pain. Just after Yorktown, Alexander had learned of the death of his half brother, Peter Lavien, who’d taken Alexander’s books after their mother died. In his will, the wealthy Peter left Alexander and James a pittance: 150 pounds sterling. He even got James’s name wrong, calling him Robert.

Alexander wrote about it to Eliza: “You know the circumstances that abate my distress, yet my heart acknowledges the rights of a brother. He dies rich, but has disposed of the bulk of his fortune to strangers. I am told he has left me a legacy. I did not inquire how much.”

He wanted to do better by his own family, saying many times he was ready to put public service aside for private life. But his ambition was unquenchable. Since Yorktown and his convalescence, he’d thrown himself into activity.

Picking up where he’d left off at King’s College, he crammed years of work into six months, during which he also wrote a 177-page law manual called Practical Proceedings in the Supreme Court of the State of New York, which was so good that law students in New York State would use it for decades.

In part, he had Aaron Burr to thank for the swiftness of his law degree. While Alexander was recuperating after Yorktown, Burr petitioned the New York Supreme Court to allow veterans who’d started studying law before the war to skip the customary three-year apprenticeship.

HE SIGNED IT, “YRS FOR EVER.”

There was reason to rush. Alexander had waived his military pay, and he needed money to support his family. There would be many clients eager for representation once the dust of war had settled, and he intended to be ready.

He also wrote more “Continentalist” essays, continuing to explain how a federal government should look. At the outset of the war, no one had any idea how to establish a governing body for a new, independent nation. Anyone who said otherwise was kidding themselves. People were used to living life as colonists. They had to be led into a new world—one that embraced the reality of taxation by people who’d gone to war in protest of the same thing.

In June, he’d been appointed tax collector for New York, and it was an exercise in frustration. The nation had war debt to pay, both to soldiers and other countries. There was no independent source of revenue for the federal government, and some people were operating under the delusion that taxes were optional. The Articles of Confederation, which had been developed by Congress in 1777, made no provision for taxes and needed deep revision. He’d realized as much during the war and wished others would as well.

But that wasn’t the extent of his public service. He’d also been elected to represent his state in Congress. His friend John Laurens was thrilled to see Alexander take office. The nation needed his services. For his part, Laurens had resumed “the black project,” as he called his efforts to integrate the army, as a stepping-stone to emancipation. He didn’t prevail, but he was heartened by his progress in the cause:

“I was out-voted, having only reason on my side, and being opposed by a triple-headed monster that shed the baneful influence of Avarice, prejudice, and pusillanimity in all our Assemblies. It was some consolation to me, however, to find that philosophy and truth had made some little progress since my last effort, as I obtained twice as many suffrages as before.”

Alexander wrote back with an idea: Laurens could join him in politics. Together, they’d build a new nation that would withstand every challenge:

“Quit your sword my friend, put on the toga, come to Congress. We know each other’s sentiments, our views are the same: we have fought side by side to make America free, let us hand in hand struggle to make her happy.”

He signed it, “Yrs for ever.”

Twelve days after he wrote it, a handful of British soldiers were scavenging rice growing near the Combahee River in South Carolina’s low country. Laurens wanted to go after them but was ordered to stand down. Laurens’s reckless heart wouldn’t listen. The British, who’d been tipped off, were waiting. As Laurens raced forward in attack, he was shot and killed. He was one of the last Americans to die in the Revolution. One of the last, and one of the best.

“Intrepidity bordering on rashness,” Washington said of him.

Laurens probably never received Alexander’s letter.

Alexander wrote of his grief to Lafayette in Paris. “You know how truly I loved him and will judge how much I regret him.”

He wrote to Nathanael Greene, too. “How strangely are human affairs conducted, that so many excellent qualities could not ensure a more happy fate? The world will feel the loss of a man who has left few like him behind, and America of a citizen whose heart realized that patriotism of which others only talk.”

By November, now forever without his political soulmate, Alexander made his way to Philadelphia for his first term in Congress. Alexander hated how the delegates pandered to their constituents, trying to please them rather than doing the right thing for the nation as a whole. Even before he’d taken office, he vented his frustration in a letter to Robert Morris, who was still the superintendent of finance.

“The more I see, the more I find reason for those who love this country to weep over its blindness,” he wrote.

His first order of business was to see that the federal government, as weak as it was, had revenue. Walking away from America’s debts, as some wanted to do, would be disastrous. A nation had to pay what it owed. A fellow congressman, James Madison, agreed that a 5 percent federal duty on imported goods was the best way to raise funds.

It would be a tough idea to rally people around. Taxes were unpopular, to say the least. An import duty also meant the federal government could write laws that applied to citizens of all the states. To grant the federal government this much power worried some. It felt too much like a monarchy for the newly independent revolutionaries.

Despite the political challenges, they had no time to waste. As the Revolutionary War drew to an end, the terms of peace with England were being hammered out. This alarmed officers of the Continental Army, who feared they’d never be paid if the treaty was signed first. Violence was a real possibility.

VIOLENCE WAS A REAL POSSIBILITY.

As Alexander allied with Madison on the matter of taxes, he looked to another man for an alliance on leadership: George Washington. For the first time since he’d sent his resignation letter in March, Alexander wrote to Washington, informing him that Congress and the army were headed for a showdown. Alexander asked—confidentially—for Washington to lend his wisdom and influence to the task of settling this for the good of all. He let Washington know the country’s finances were in terrible shape. The nation had to establish a fund to pay the country’s debts. To do this, he wanted Washington to secretly use his influence to have the army apply pressure to Congress.

Washington, grateful, wrote back a few weeks later. He wished Congress had told him things were dire. That said, he insisted it would be a terrible idea for the army to take on the government directly. That overstepped the army’s authority in a dangerous way. And it wasn’t necessary: The army’s claims were just, and sensible legislators would see the facts once they’d been presented. What’s more, Congress needed more centralized authority, or all the blood they’d spilled over the eight years of war would achieve nothing.

With that, the two men were allies again—this time not to defeat a foreign enemy but to figure out how to build an enduring nation out of hopes, dreams, and difficult realities. The alliance was still tentative. Much had passed between them. But the nation needed them, just as they needed each other.

BUT THE NATION NEEDED THEM, JUST AS THEY NEEDED EACH OTHER.

A few days later, Alexander received more news from Washington. An anonymous letter circulating around an army camp in Newburgh, New York, demanded a military solution to the financial problems of Congress—in other words, a coup. Washington called for a meeting on March 15, where he urged his army officers to act with honor, dignity, and transparency:

“You will give one more distinguished proof of unexampled patriotism and patient virtue, rising superior to the pressure of the most complicated sufferings.”

The men weren’t persuaded. They wanted their money. Facing the failure of his prepared speech, Washington gambled. He unfolded a letter from a Virginia congressman explaining the financial straits of the government. And then he squinted and reached for a pair of eyeglasses.

“I have not only grown gray but almost blind in the service of my country,” he disclosed. It wasn’t like him to reveal vulnerabilities, especially ones of such a personal nature. The gesture shamed the men into listening.

Washington’s delivery was positively Hamiltonian. Later, Washington made the soldiers’ case before Congress, and Alexander led the committee that agreed to pay the officers a pension worth five years’ salary. Congress didn’t yet have the money, but the government had made clear its intentions to honor the country’s financial obligations.

Alexander was relieved. He saw now that if the army had used force, it could have started a civil war that would ruin the military, if not the country.

Meanwhile, much was unsettled. The peace treaty with England had not yet been signed. There were still matters of international debt to hammer out. The war had been won, yes. But it seemed as though the real work was only beginning.

DURING THE SPRING AND SUMMER OF 1783, Alexander’s shoulders sagged with challenges. Congress had officially ended the fighting in April. But this didn’t mean the need for military protection had evaporated. On the contrary, troops were needed to keep the peace and protect the borders and harbors, and Alexander had to figure out how a peacetime army would work, and how state militias would coordinate.

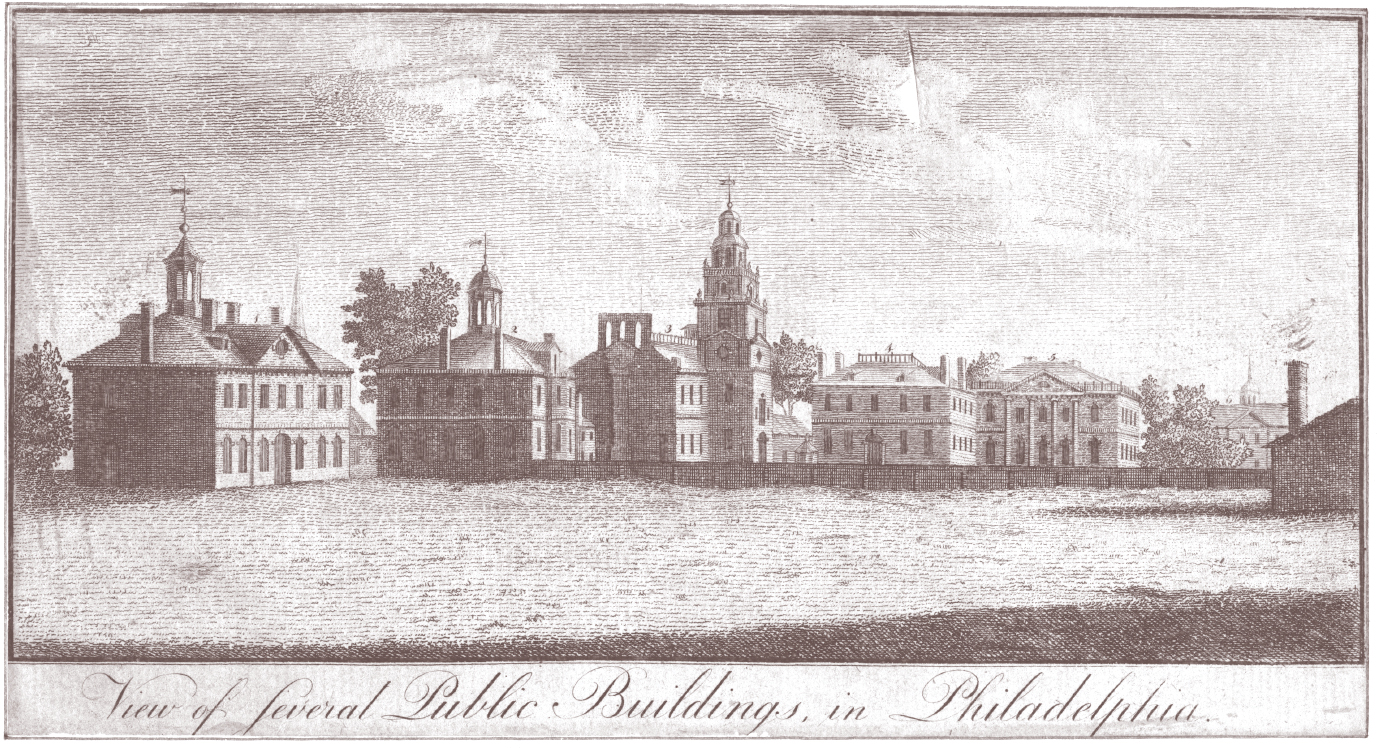

A ROW OF PHILADELPHIA’S PUBLIC BUILDINGS CIRCA 1790.

Meanwhile, the unpaid army was running out of patience. On June 19, Congress learned that eighty angry soldiers from a Lancaster regiment were marching toward the capital in Philadelphia. They were going to get their money or else—and other soldiers were joining them on the way.

By the time the angry rabble arrived in Philadelphia and seized a military barracks, Congress had already adjourned for the weekend. Elias Boudinot, the president of Congress, called for a Saturday session. Before the congressmen had fully gathered, about four hundred soldiers—who vastly outnumbered the loyal guards—surrounded the State House. The mutineers sent in a note that gave the politicians twenty minutes to respond. If their grievances weren’t heard in that time, they’d set the soldiers loose.

Many of the soldiers were drunk and getting drunker. Rumors flew that the furious men might also seize control of the city’s bank. Congress refused to negotiate under such a menace, and by three thirty in the afternoon, the mutineers were persuaded to return to the barracks.

That night, Alexander and the rest of Congress met at Boudinot’s home. Alexander, furious to be threatened by a mob, dashed off a resolution. The attempted military coup had been disorderly, menacing, and grossly insulting, “and the peace of this City being endangered by the mutinous disposition of the said troops now in the barracks, it is, in the opinion of Congress, necessary that effectual measures be immediately taken for supporting the public authority.”

Either Pennsylvania would act to protect the authority of government, or Congress would leave town. Pennsylvania failed to respond fast enough. By Thursday, Congress had set up shop temporarily in Princeton. The mutiny ended when state leaders finally called up five hundred militiamen.

Afterward, Congress wouldn’t have a stable home again for two years. It moved from Princeton to Annapolis to Trenton and finally New York in 1785. The frustration rankled. The states had too much power and influence and tended to hoard it rather than look to the needs of the nation.

THE TREATY OF PARIS, SIGNED IN 1783, ESTABLISHED NEW BORDERS FOR THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA.

Fed up, Alexander wrote a resolution in July, calling the Articles of Confederation “defective.” He outlined its many broken elements: Its powers were too limited. Legislative, executive, and judicial powers needed to be separated. State and local regulations were impeding international treaties. Money was needed to provide for the common defense, but states weren’t willing to uniformly contribute. Congress could borrow money without having the means to repay it. Printed money was rapidly shrinking in value, and the public credit of the infant nation was being destroyed. Leaving defense to states led to inequities, confusion, and conflict. Likewise, the economy would grow better with centralized oversight of taxes and regulations.

In short, the United States had to start acting like a nation and not a flimsy confederation of states. Revising the Articles of Confederation, which had taken four years to ratify, would be difficult. Even so, Alexander intended to submit his vision for a new nation to Congress.

Despite his best efforts, he couldn’t rally enough support. Indeed, some people thought Congress too powerful already. Thomas Jefferson, who’d written the Declaration of Independence, thought the work of the federal government could be done by a committee.

Alexander and Jefferson could not have been cut from more different bolts of cloth.

Jefferson had thought the war would be over quickly. Unlike Alexander, he had not thrown himself into the study of military principles and learned to become a soldier and leader when war broke out. Jefferson had behaved timidly on the battlefield, running from danger when he’d served as Virginia’s governor and enabling Benedict Arnold to capture Richmond. Jefferson was in many ways Alexander’s opposite: born to privilege, an owner of slaves, someone who envisioned an agrarian rather than a modern United States.

UNLIKE ALEXANDER, THOMAS JEFFERSON WAS BORN TO PRIVILEGE AND PERFORMED POORLY IN BATTLE.

The first battle lines between them were drawn—and it would be a long war with surprising turns.

After beating his head against a wall for months, Alexander wanted only to be home with his wife and son. On July 22, he wrote to his beloved, hoping that in four days’ time he’d be headed her way.

“I am strongly urged to stay a few days for the ratification of the treaty; at all events however I will not be long from My Betsey. I give you joy my angel of the happy conclusion of the important work in which your country has been engaged. Now in a very short time I hope we shall be happily settled in New York. My love to your father. Kiss my boy a thousand times. A thousand loves to yourself.”

HE WAS AT HOME ON NOVEMBER 25, 1783, WHEN the British finally left New York. Alexander’s former military commander Henry Knox secured the city with his troops. Meanwhile, George Washington and the state’s governor, George Clinton, rode into the jubilant town on horseback. A parade of soldiers marched the general from the Bowery to Wall Street, where Alexander, Eliza, and Philip lived.

The bedraggled patriots looked nothing like the departing British soldiers, who had scarlet uniforms and polished weapons. The American troops wore mismatched uniforms tattered by weather and use. But New York felt pride in these men and loathing for the British soldiers, who were such sore losers they greased the liberty pole on their way out, making it hard for the Americans to hang their Stars and Stripes.

Patriots resented the British and their Tory sympathizers. Even Hercules Mulligan was endangered by it. So many people believed he was a traitor that Washington needed to have breakfast with him after the parade, to show the nation whose side Mulligan had really been on.

WALL STREET IN NEW YORK, HERE CIRCA 1785, STARTED AS A DEFENSIVE BOUNDARY, BECAME A SLAVE MARKET, AND TURNED INTO THE FINANCIAL CAPITAL OF THE UNITED STATES.

It didn’t help the Tories that New York was a shambles. Much of the city had been destroyed by a fire in September 1776, and the British had not repaired things during their seven-year occupation. They’d burned fences and trees to keep warm. The wharves were falling apart, and shanties had popped up everywhere.

Alexander had grand ideas for how the city could be restored and how carpenters and masons could be put to work building large and elegant structures, and he would make the case for his fellow citizens in the months and years to come.

But the city couldn’t be rebuilt on a foundation of resentment. Alexander was outraged at the treatment of Tories and the way it was causing them—and their money and business ties—to leave in waves for Canada. These were not the values he’d risked his life for, and it was putting the economic health of the city in jeopardy.

As ardently as he’d fought and managed the Revolution, he took up the cause of the loyalists who remained. Yes, they’d stood for the wrong values and aligned with the wrong forces. But they still had rights. The country would need to be stitched together of friends and former foes alike—and new laws restricting civil and property rights struck Alexander as being counter to the spirit of the country’s founding principles. The way America treated its citizens—even the ones who’d been on the wrong side of history—would affect its standing internationally.

HE WASN’T MOTIVATED BY POPULARITY. NOT EVEN BY PROFIT.

He welcomed downtrodden loyalists as his clients, and soon, he was one of the most respected lawyers in the city. But he didn’t limit his efforts on their behalf to the courtroom. In early 1784, he adopted the pen name Phocion, arguing in print against retribution and unjust treatment of sympathizers to the Crown.

“Nothing is more common than for a free people, in times of heat and violence, to gratify momentary passions, by letting into the government, principles and precedents which afterwards prove fatal to themselves,” he wrote. This included disenfranchisement of broad classes of citizens, which could lead to aristocracy or oligarchy. Only due process—trial and conviction in a court of law—justified taking away a person’s rights.

He wasn’t motivated by popularity. Not even by profit. Though he joked to Lafayette that he was rocking the cradle and studying the art of fleecing his neighbors, if anything, he undercharged for his services. Alexander’s passion was for principles, not profits. He once declined a client’s promise to pay a $1,000 retainer because it was too much money.

Alexander challenged state laws that violated the treaty with England. He argued for justice systematically, passionately, and at length. (His college friend and study partner Robert Troup teased that Alexander never settled for delivering a blow to his opponent’s head when he could slap down the insects buzzing around his fallen enemy’s ears.) He kept his eyes on his long-term goal: creating a strong central government. Challenging laws that broke the international treaty was crucial. A state should not be able to pass laws that would violate those of the country as a whole. There was no more important way to establish the hierarchy between individual states and the nation. Nation first.

Not everybody saw it this way, and the fight for power between the states and the federal government would only grow.

As Alexander ascended the ranks of the city’s lawyers, he was joined at the top by Aaron Burr. On the surface, the men had much in common. Both had been orphaned early. Both were ambitious students and ardent admirers of women. Both fell in love during the war. Both had become lawyers on a fast path, and both were doting fathers, though only one of the children Burr had with his wife survived.

But their paths began to diverge during the war and split widely afterward. Burr and Washington didn’t care for each other, and Burr had been one of Charles Lee’s defenders after his reckless retreat at Monmouth. Alexander and Burr differed in the courtroom, too. Where the blue-eyed Alexander spoke volumes and sometimes got himself into trouble with his mouth, black-eyed Burr was more guarded. He cultivated this obscurity and described himself in the third person, as if he were talking about someone else: “He is a grave, silent strange sort of animal, inasmuch that we know not what to make of him.”

AARON BURR AND ALEXANDER WERE FRIENDS, THEN RIVALS, THEN BITTER ENEMIES.

Burr even obscured body parts he didn’t want people to see. He styled his dark hair so that it hid his small ears and, when he started going bald on top, arranged an elaborate comb-over to conceal his visible scalp.

Unlike Alexander, he charged steep fees and lived lavishly. Where Alexander cleaved to principles, Burr clutched at power.

They sometimes worked the same side of cases in the courtroom, though not always happily. Once, when they argued a case together, Alexander wanted to take the lead. Burr, irritated at this, anticipated all Alexander’s arguments, leaving him no spotlight to stand in. Alexander sat down without arguing a single point.

WHERE ALEXANDER CLEAVED TO PRINCIPLES, BURR CLUTCHED AT POWER.

But they weren’t always rivals. Burr helped Alexander become a homeowner in 1785—he was the one who tipped Alexander off that 57 Wall Street was for sale. In the distant future, they would work as allies defending a man in a sex-tinged murder-mystery trial, the first murder trial ever to be recorded in the United States. But no alliance between them would ever last, and neither could have predicted how dark their rivalry would become, or how deadly.

ALEXANDER WAS TOO BUSY EVEN TO CONSIDER such things. The year before he bought that first house, he’d transformed the financial prospects of his fellow New Yorkers.

It all started as a favor to his brother-in-law John B. Church. Church had made a fortune overseas and had invested some of that capital in the Bank of North America, the first such bank in the nation, established in 1781 in Philadelphia. Church wanted similar investment opportunity, so he and his business partner asked Alexander to set up a private bank in New York.

At the time, there were two ways to fund a bank: with land or with money (paper or coins made of silver and gold). Land was the more conservative option. But it’s not a very flexible one. You can’t turn it into cash immediately. So, when a rival proposed a land-based bank to merchants, Alexander used his deep knowledge of finance to persuade the merchants that it was the wrong route to take. He made such a compelling case that the merchants asked him to set up a money bank on their behalf. And so he did, feeling slightly chagrined at having overstepped his initial goal.

HAMILTON HAD PLANTED THE SEEDS FOR THE MODERN AMERICAN BANKING SYSTEM.

A newspaper advertisement invited interested people to meet on February 24, 1784, at the Merchant’s Coffee House. Before the Revolution, the Sons of Liberty sometimes met there. Now it was the founding place for the city’s first bank.

Alexander was named a director. General Alexander McDougall, an army colleague, was chairman. Over the next three weeks, Alexander threw himself into the challenge of how the bank would work. He single-handedly created a constitution that outlined, in twenty crisply written articles, how the bank would run. It was so good that other banks used it as their model. And so, without really meaning to do anything other than help his brother-in-law, Alexander Hamilton had planted the seeds for the modern American banking system.

ALEXANDER HAD A KNACK FOR INSERTING HIMSELF into controversial debates without fearing or even always anticipating the consequences. Because he represented loyalists in court, people wondered whether he was secretly one of them. He also believed that institutions like banks would be an integral part of a modern nation, and people accused him, falsely, of profiting from the one he had set up. He thought there should be a strong, centralized federal government, and people thought he was a closet monarchist. He retained his disgust at the practice of enslaving other human beings, and later some people claimed he was Creole himself.

With the matter of slavery, Alexander was compromised. Not only did associates like Washington keep many people enslaved, his wife’s parents bought enslaved people and put them to work on their estate and in their fields and mills. Angelica and her husband owned people. What’s more, Alexander helped negotiate human purchases on behalf of his in-laws. He had their blood and sweat on his hands.

On the surface, it was a clear issue morally for Alexander. A nation founded on principles of equality and liberty had no place forcing human beings into slavery. Human freedom also trumped the principle of property ownership that Alexander held dear. Enslaved people who’d been promised their freedom in exchange for fighting were entitled to their liberty. It didn’t matter whose side they’d fought on.

ALEXANDER CONTINUED TO OPPOSE SLAVERY BY JOINING THE NEW YORK SOCIETY FOR PROMOTING THE MANUMISSION OF SLAVES.

Some people objected to ratifying the peace treaty with England unless the king reimbursed enslaved people’s former owners for their loss of human “property.” But Alexander disagreed. The enslaved people, once freed, were no longer property. No one was owed anything.

“The abandonment of [enslaved black people], who had been induced to quit their Masters on the faith of Official proclamations promising them liberty, to fall again under the yoke of their masters and into slavery is as odious and immoral a thing as can be conceived.”

This didn’t stop enslavers from traveling to New York and other cities and snatching black people off the streets, regardless of whether they had been given their freedom or had freed themselves. Partly out of outrage for this practice of abduction, the New York Society for Promoting the Manumission of Slaves formed on January 25, 1785.

Robert Troup—who owned two enslaved people himself—was one of the founders, more than half of whom owned enslaved people. Soon afterward, Alexander joined the society, attending a meeting at the Merchant’s Coffee House. Everyone agreed that the corrupt practice of enslaving other human beings needed to end, but how and when?

Alexander, Troup, and a fellow volunteer worked together on a solution, which they presented in November 1785 with details about timing and methods. As happened so often with Alexander, he was too ardent and aggressive with his ideas and couldn’t rally people behind them. He kept at it, though. A few months later, he helped lobby the state legislature to stop the trade of enslaved people in New York, who were being treated like cattle as they were exported to the West Indies and the southern states.

The society would later found the New York African Free School in 1787. It wasn’t the only school Alexander would have a hand in starting. He also became a trustee of a school for Oneida Indians and the children of white settlers, although few members of the tribe chose to go to the school, whose purpose was to help them assimilate into the culture of their colonizers.

IN THE FLURRY OF COURT CASES AND CIVIC activity, his role as family man was growing ever larger. Little Philip got a sister, Angelica, on September 25, 1784. More children would follow. In 1787, the Hamiltons also took in a two-year-old girl named Fanny after her mother died and her father was overwhelmed. Alexander doted on his family. When Eliza had a cold, he’d urge her to take good care of herself, lest she suffer pain and lose out on life’s pleasures. He listened to little Angelica play the piano and sing. And he included his extended family, especially Eliza’s sister Angelica, in his deep affections. When Angelica moved overseas, he mourned the loss:

“I confess for my own part I see one great source of happiness snatched away. My affection for Church and yourself made me anticipate much enjoyment in your friendship and neighbourhood. But an ocean is now to separate us.”

As his understanding of what it meant to have a family grew, the memory of his childhood experience ached. He’d neglected to write Hugh Knox and felt the shame of that. Worse, he hadn’t heard from his brother, James, in years. Maybe James had a wife and family—Alexander had no idea. It was his dream someday to set his brother up on a farm in the United States, but the postwar economic chaos was too great to make that possible at the moment.

When he finally did hear from James on June 22, 1785, the letter made him sad. He responded with an offer of help and love: “The situation you describe yourself to be in gives me much pain, and nothing will make me happier than, as far as may be in my power, to contribute to your relief. I will cheerfully pay your draft upon me for fifty pounds sterling, whenever it shall appear. I wish it was in my power to desire you to enlarge the sum; but though my future prospects are of the most flattering kind my present engagements would render it inconvenient to me to advance you a larger sum. My affection for you, however, will not permit me to be inattentive to your welfare, and I hope time will prove to you that I feel all the sentiment of a brother.”

Becoming a father had made him miss his own, even though he hadn’t seen the man in decades. His father still hadn’t met Eliza, as Alexander had promised on their wedding day. The man hadn’t seen any of his grandchildren. He didn’t even know of their existence. Alexander worried his father was dead, and the thought of it, and how difficult his father’s life had been, weighed on his heart like lead. He liked to fantasize that his uncles had helped lift his father’s prospects, but feared that had not been the case.

He told James, “Let me know how or where he is, if alive, if dead, how and where he died. Should he be alive inform him of my inquiries, beg him to write to me, and tell him how ready I shall be to devote myself and all I have to his accommodation and happiness.”

As for his own children, he hated to be away.

“I feel that nothing can ever compensate for the loss of the enjoyments I leave at home, or can ever put my heart at tolerable ease,” he told Eliza. “In the bosom of my family alone must my happiness be sought, and in that of my Betsey is every thing that is charming to me. Would to heaven I were there!”

But he couldn’t be home on Wall Street all the time. The young father was needed not just as father of his children, but as father of a nation. His fighting with musket and bayonet was done. But his most powerful weapon—his mind—was about to be unleashed.

It would be unlike anything the world had ever seen.