ELIZA SAT FOR THIS PORTRAIT, BY RALPH EARL, IN DEBTORS’ PRISON.

IN 1780, ALEXANDER HAD written a letter to his fiancée. The war was not yet won, its outcome not yet certain. Indeed, South Carolina had just been lost. His best friend was a prisoner of war, and Alexander—who’d wanted to fight by Laurens’s side but couldn’t—was overwhelmed with paperwork instead. The French fleet had arrived, and Alexander was charged with figuring out three different approaches for how the two nations might combine their militaries.

The workload left him gloomy. But he did find some sources of hope. There was the glow of Eliza’s love, and his gut instinct that the political challenges the war had revealed could be fixed with reform of the Articles of Confederation. He was embarrassed to be musing on such matters in a love letter, but he couldn’t help it.

“Pardon me my love for talking politics to you. What have we to do with any thing but love? Go the world as it will, in each others arms we cannot but be happy.”

That said, if things didn’t work out with the war, he had other ideas. “What think you of Geneva as a retreat? ’Tis a charming place; where nature and society are in their greatest perfection. I was once determined to let my existence and American liberty end together. My Betsey has given me a motive to outlive my pride.”

Eventually, the war did end. He’d married the girl. But the work remained unfinished, including repairing all that was broken with the Articles of Confederation. By 1786, the rest of the nation was finally catching up with Alexander’s understanding of the situation.

Tensions crackled between the states. In New York, Governor Clinton had imposed import taxes that local merchants despised. What’s more, other states receiving parts of those shipments—like nearby New Jersey—weren’t receiving income from the taxes. Maryland and Virginia were squabbling over the Potomac River—the conflicts went on and on. Every state was acting in its own interests, and the nation was suffering.

Alexander could see the scope of the disaster as it unfolded on every level. The countries that had loaned America money during the war weren’t sure they’d be paid back, which was destroying America’s credit potential overseas. States were hoarding tax revenue for themselves instead of fulfilling their commitment to make voluntary payments to the federal treasury. States were also taking advantage of each other, which was a recipe for civil war and an open door to meddling from foreign powers.

In the summer of 1786, thousands of farmers overwhelmed by bad crops, a depressed economy, and oppressive taxes put on their army uniforms and rebelled. Alexander sympathized with their cause, but mob violence wasn’t the solution.

The truth was, people were suffering because Congress couldn’t get the nation’s finances in order. It wasn’t just on a national level. Alexander felt it personally. Good people suffered. Baron von Steuben was to have been paid if the patriots won. And yet he was forced to come to Alexander for personal loans. Ralph Earl was an artist who’d painted battlefield scenes. He went to debtors’ prison in 1786. Alexander and Eliza helped Earl earn his way out the next year, when Eliza sat for Earl in jail as he painted her portrait.

Sometimes it felt as if the public’s appetite for his services was endless. He’d fought in the war. He’d surrendered his pay. He’d collected taxes. He’d served in the Continental Congress. And then, in September 1, 1786, he was asked again to take time away from his law practice. The states were fighting among themselves, and he and delegates from other states needed to resolve it.

ELIZA SAT FOR THIS PORTRAIT, BY RALPH EARL, IN DEBTORS’ PRISON.

So, he set off for Annapolis. He fell ill on the road and was in low spirits as a result. What’s more, he was one of only a few who responded to the call of duty. Just a dozen delegates from five states gathered in the city, chosen because it was small and far away from Congress, so no one would accuse them of being biased.

In a way, this relative apathy was good. Alexander was among friends, including James Madison. Alexander’s fellow New Yorker, Egbert Benson, took notes, and before long, they’d all agreed that the real problem was this: the balance between state and national influence had not yet been resolved. The Articles of Confederation needed revision. Alexander was so excited by the prospect that he unloaded the verbal equivalent of a howitzer as he made the case to Congress. His enthusiasm didn’t go over well. The quiet, scholarly Madison had to walk him back to reality.

With Madison’s influence, the revised document took a gentler tone, letting Congress know it was time to revise the Articles of Confederation. The situation was critical. The proposal set a date and a place. Philadelphia, the second Monday of May in 1787. They would devise a constitution adequate to the needs of the nation. They’d get Congress to approve it, and then take it to the states for ratification.

ALEXANDER’S GLEE DIDN’T LAST LONG. WHEN he returned home, his own governor, George Clinton, opposed the reform plan. Clinton, a political rival of Alexander’s father-in-law and resolute believer in the rights of states over the federal government, made sure Alexander was surrounded by oppositional New Yorkers at the Constitutional Convention. It was the worst possible sort of baggage for him to carry to Philadelphia.

Delegates began to arrive in Philadelphia in early May. Delayed by weather, like so many other delegates, Alexander arrived on Friday, May 18, wearing a three-piece wool suit in the midst of a heat wave. A visiting Frenchman said of the weather, “The heat of the day makes one long for bedtime because of weariness, and a single fly which has gained entrance to your room in spite of all precautions, drives you from your bed.”

As the days passed, the city swelled with delegates, and it wasn’t always easy to find inns to accommodate them. Washington, now fifty-five years old, had aching joints and had only attended at the urging of friends. He hated idling away his time when he had a plantation to run.

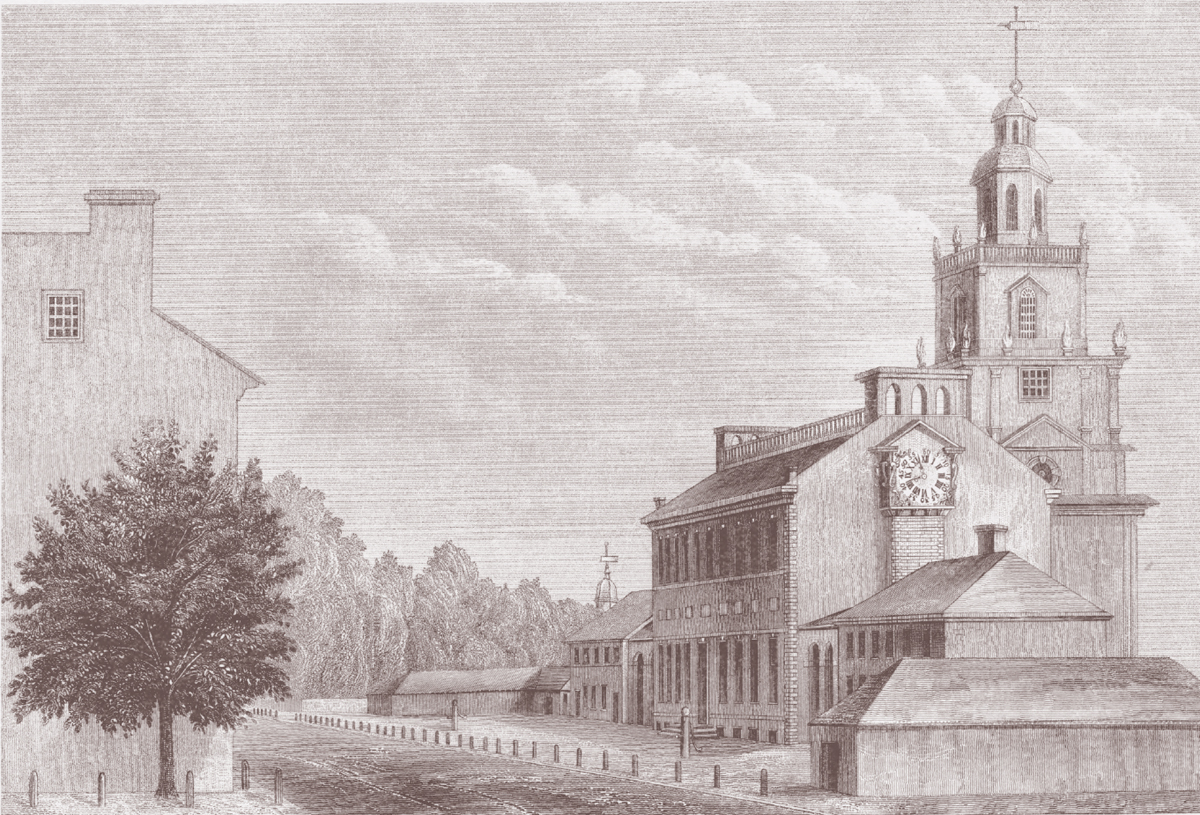

THE CONSTITUTION WAS WRITTEN IN INDEPENDENCE HALL, PHILADELPHIA, DEPICTED HERE IN 1778.

Finally, on May 25, enough men had arrived that work could begin. It was an “assembly of demigods,” in the view of Thomas Jefferson, whose duties kept him in France. Alexander knew many: Washington, James McHenry, Robert Morris, James Madison, and Gouverneur Morris, a fellow lawyer and the friend he’d talked into slapping Washington’s back that one time. Even Ben Franklin was there. Alexander hadn’t met the legend yet but was eager to.

They met in the Pennsylvania State House—later known as Independence Hall—where the Declaration of Independence had been signed eleven years earlier, when Alexander had been a bright-eyed artillery captain, eager for war and glory. He was more than that now. He’d had his war. He’d achieved his glory. In the midst, he had suffered and seen good men die. He had watched the army struggle because of defects with the Articles of Confederation and selfishness on the part of the states. This was his chance to change everything.

In some ways, the Revolution had been the easier part. Now they had to create a functioning government, a complex, high-stakes challenge that would determine the happiness or misery of millions of unborn people, as one senior delegate, sixty-one-year-old George Mason, observed.

WHAT WAS SAID IN THE ROOM STAYED IN THE ROOM.

Alexander was one of three men in charge of coming up with rules for the convention. An early and controversial rule established confidentiality: what was said in the room stayed in the room. This was to let the participants freely share their thoughts and arrive at the best possible conclusions. The secrecy was so vital that the doors and windows remained closed despite the heat.

Washington, elected leader, presided from a table at the front of the room. His mahogany chair featured a brilliantly painted golden sun carved into its crest rail. Facing him, the fifty-five delegates sat in plain Windsor chairs at tables topped with green cloths, inkwells, quills, writing paper, and books of philosophy and history they could consult as they worked. Men stood to face Washington as they spoke, and no one was permitted to interrupt or read from books or pamphlets when someone had the floor. Another rule required the men to stand at the end of each day, waiting to leave until Washington had passed.

EDMUND RANDOLPH WAS ONE OF THE YOUNGEST FOUNDING FATHERS. HE AND JAMES MADISON PROPOSED A GOVERNMENT WITH A TWO-PART CONGRESS.

To Alexander’s relief, it quickly became clear that the Articles of Confederation were up for more than revision. He kept mostly mum as other men proposed their plans. Alexander had some dramatic ideas to reveal, but he was biding his time for the right moment.

Edmund Randolph of Virginia, at thirty-three years old one of the youngest men in the room along with Alexander, presented a plan he and Madison had devised. Their Virginia plan envisioned a two-part congress, the first part elected by the people and the second elected by the first, out of nominees provided by the state legislatures. Congress would choose the single executive. Representation would be based on state population. Virginia, as the largest state, had a vested interest in the sort of power it would give.

Delegates debated the plan, article by article, for days. Alexander remained silent as he observed the others. He had reservations about democracy and its potential for excesses. Tyranny was dangerous, but so were mobs. He’d seen them again and again—in the West Indies, at the outbreak of the Revolution, and afterward, with the soldiers who’d surrounded Congress with their guns, demanding money the government did not have.

Thinking about how he could make his case, Alexander spoke only rarely in the early days of the convention—once to second a motion by Ben Franklin that the executive of the federal government do the job for free. It wasn’t a practical idea, and the delegates didn’t vote on it, but Alexander especially wanted to honor the man, who was old and sick.

An alternative to Randolph’s plan came from New Jersey delegate William Paterson, an Irish immigrant who’d studied law in Princeton. It represented a revision to the Articles of Confederation instead of a wholesale new constitution. His plan would establish one legislative house, allow the federal government to raise money with tariffs and stamp taxes, and establish an executive council elected by the Congress and subject to removal by a majority of the state governors. A primary goal was to balance the power between large and small states.

WILLIAM PATERSON FROM NEW JERSEY ARGUED FOR REVISION OF THE ARTICLES OF CONFEDERATION.

Debate over the two plans highlighted the biggest points of contention: the hierarchy of the national and state governments and the balance of power between states of different sizes.

Alexander believed passionately in the importance of a strong federal government. Weak federal power had nearly cost them the war. After listening to both plans and considering the wisdom of men with more experience—feeling reluctant to disagree with them—he could no longer hold back.

On June 18, he filled his lungs with a great deal of air, stood to face Washington, and for the next six hours outlined his bold vision for a new nation. He didn’t care at all for the New Jersey plan. Proposals for popular governments were the same old pork, “with a little change of sauce.” What the nation needed, he argued, was a balance between tyranny and the excesses of democracy. His plan included a two-part legislative body. The assembly would be elected to three-year terms. The senate would be chosen by electors voted on by the people. Senators would serve for life, barring misbehavior. This would provide necessary continuity. Judges on a supreme court would serve similar lifetime appointments.

“I AM SORRY YOU WENT AWAY—I WISH YOU WERE BACK.”

Meanwhile, the United States legislature could appoint courts in each state. Any state laws that contradicted national ones or the constitution would be void. And no state would have its own army or navy; there would be just one for the nation as a whole.

A supreme executive authority, which some listeners heard as “monarch,” would be a governor elected by electors chosen by the people. He would serve for life, except in cases of misbehavior. He’d have veto power over the legislature and command the navy and militia.

Alexander probably couldn’t have uttered a more controversial notion than one that smacked of monarchy. He also praised the British system of government, another unwise move.

A Georgia delegate named William Pierce took notes on Alexander’s performance. “Colo. Hamilton is deservedly celebrated for his talents…. Yet there is something too feeble in his voice to be equal to the strains of oratory…. His manners are tinctured with stifness, and sometimes with a degree of vanity that is highly disagreable.”

When Alexander’s marathon speech ended, the overheated audience clapped politely. No one bothered to dignify it with a rebuttal. The men were getting nowhere. Alexander, discouraged that the miracle of the convention was being squandered in a stalemate, slouched back to New York to take care of business.

He wrote to Washington: “I own to you Sir that I am seriously and deeply distressed at the aspect of the Councils which prevailed when I left Philadelphia…. I shall of necessity remain here ten or twelve days; if I have reason to believe that my attendance at Philadelphia will not be mere waste of time, I shall after that period rejoin the Convention.”

Without bringing up Alexander’s impolitic ideas, Washington commiserated: “The Men who oppose a strong & energetic government are, in my opinion, narrow minded politicians, or are under the influence of local views.”

What’s more, Washington missed his protégé. “I am sorry you went away—I wish you were back.”

The convention lasted four long months. Alexander’s fellow New York representatives left on principle in early July. They wouldn’t agree to surrender their state’s power to federal authority. They also no longer felt bound to keep confidential what had been said. In the middle of July, while Alexander was in New York, the Connecticut Compromise helped break the stalemate, which had become snagged on the balance of power between the states. To that end, each state would have the same number of senators, and votes in the House of Representatives would be proportionate to their populations. It was a delicate but necessary compromise.

There were other demanding issues to resolve, not the least of which was slavery. It was a bitterly divisive issue between the North and South. Rather than pick at the wounds, some delegates used euphemisms when talking about the institution, calling enslaved people “persons held to Service or Labour” and the slave trade “migrations,” which suggested a natural or elective pattern of movement at odds with reality.

The debate wasn’t about liberty for enslaved people, though. It was about power for their masters. Delegates from the slave states wanted their representation in the House to reflect their human property, increasing their clout in the legislature. A compromise was struck: enslaved people would count as three-fifths of a person (though they would not be allowed to vote).

The compromise depressed Alexander, who deepened his commitment to the Manumission Society.

Here, Alexander walked a difficult line. He had on occasion compromised his principles for political or personal reasons. Acting on orders during the war, for example, he participated in efforts to track down an enslaved man who’d joined the British and been taken captive. In Congress shortly after the war ended, he put forward a motion to protest General Guy Carleton’s refusal to return formerly enslaved people who’d sought refuge behind British lines. Some of his friends in the Manumission Society continued to enslave people, even after joining. Alexander determined how those society members should treat their human property—a different tack from arguing for immediate freedom. And then there were the enslaved people owned by his relatives.

The union trumped all other beliefs, though. Without the three-fifths compromise, the whole enterprise would have been sunk. Some considered it unjust to give even partial representation to men who had no vote. But it was worth the compromise to keep the South and North together. The South grew staple crops, some of which were exported, and all of which benefited the nation as a whole. And then there was the argument that representation should go to property owners; enslaved men counted as property.

“THEY ARE MEN, THOUGH DEGRADED TO THE CONDITION OF SLAVERY.”

This didn’t make it just, he said later. “It will however by no means be admitted, that the slaves are considered al-together as property. They are men, though degraded to the condition of slavery.”

Another contentious issue concerned the rights immigrants had to hold office. This rankled Alexander, who’d done more than many natural-born citizens to assure the nation’s independence. Why should he be considered lesser because of the circumstances of his birth? But many in the South were wary of “foreign” interference in the nation’s business. When Alexander briefly returned to the convention on August 13, he advocated for immigrants to be able to serve in Congress or as president after spending four years in the country. Ultimately, the Constitution permitted someone who was a citizen at the time the document was signed to serve as president. Otherwise, the candidate had to be native born—which seemed a fair compromise.

Compromise became a theme toward the end of the convention. Alexander had been devoted to the idea of a strong federal government. The stronger the better, to guard against democracy run amok. He was even willing to let someone be the leader for life, if his behavior was good. And yet the notion of checks and balances among the branches of government had become reassuring enough that Alexander was fully behind the compromises that were adopted, including term limits. He even seconded a resolution by Madison on a method for amending the Constitution that required consent from the states—something he never would have agreed to in the early days of the convention. It wasn’t about achieving perfection, but rather, something closer to perfection than the Articles of Confederation had reached.

By September 8, there was enough agreement on the principles that Alexander and four other men, including Madison, sat down to capture all the articles that had been agreed to and write them in a style the subject deserved. Gouverneur Morris penned introductory words that captured the intent of the men who’d gathered:

“We the People of the United States, in Order to form a more perfect Union, establish Justice, insure domestic Tranquility, provide for the common defense, promote the general Welfare, and secure the Blessings of Liberty to ourselves and our Posterity, do ordain and establish this Constitution for the United States of America.”

Seven articles followed, outlining the contours of the federal government that would balance power among three branches: the legislative, executive, and judicial. The Constitution detailed who could run for office and how appointments to the Supreme Court would work. It set up a financial system, and its articles outlined the relationships states would have with one another and how new states would join the union. They explained how the Constitution would be amended in the future and said that the debts that existed under the Articles of Confederation were still valid. The final article established how many states would have to say yes to make the Constitution the law of the land: nine out of thirteen.

In the end, not everyone was able to see the value of political compromise and balance of powers. Edmund Randolph, who’d proposed the Virginia plan, couldn’t stomach the final document; there was too much power in the federal government.

On September 17, the Constitution was signed by thirty-nine men from twelve states. (Rhode Island hadn’t sent delegates.) Alexander was the only signer from New York. As the last names were being set to parchment, Ben Franklin, the oldest signer, made an observation about the sun carved into Washington’s chair: “I have the happiness to know that it is a rising and not a setting Sun.”

He was so pleased with the document he sent it to his friends in Europe, anticipating the day when Europe might form a similar union of its different states and kingdoms.

But it was not yet a done deal, and Randolph made a bitter prediction: “Nine states will fail to ratify the plan, and confusion must ensue.”

The official business over, Alexander and the rest of the men who’d managed to create a government without force or fraud went to the nearby City Tavern for a drink. A lot of drinks, actually. Beer, punch, madeira, cider, ale, porter, and claret, which they consumed by the light of candles made from crystallized whale oil.

TO CELEBRATE THE NEW CONSTITUTION, THE FOUNDERS DRANK LOTS OF WINE AND BEER AT THE CITY TAVERN.

When the sun rose the next day, Alexander set out to prove Randolph and other doubters wrong. On his trips home during the convention, he had faced outrageous rumors, including one that claimed the delegates had a plan to bring the second son of King George to rule America. His fellow New York delegates had also disclosed the secrets of the convention to Governor Clinton, whom Alexander accused of poisoning the electorate against the document before anyone had even read it. The battle ahead to ratify the Constitution would take every resource he had.

JAMES MADISON AND ALEXANDER WERE, AT FIRST, ALLIES.

Things turned vicious fast. Clinton had cronies write newspaper articles criticizing Alexander. One piece suggested that Alexander had weaseled his way into Washington’s family and then been fired.

“This I confess hurts my feelings,” Alexander told Washington.

Washington, who liked both Clinton and Alexander, sent a reassuring reply. “I do therefore, explicitly declare, that both charges are entirely unfounded.”

These men had no business spewing lies about what Alexander accomplished and how. They had no business undermining the work of every man in that sweltering room. What’s more, their reckless words threatened the nation. And they were an insult to his honor.

Within a few weeks, an outraged Alexander had assembled an elite intellectual and political fighting force to take on those naysayers in writing.

There was James Madison, who, while young, was a public fixture. He’d exhausted himself with study in college, and his health wasn’t robust enough for him to have been a soldier in the Revolution. He sometimes had seizures. As a congressman, Madison was widely respected for his knowledge, thoughtfulness, and persuasive speaking manner. What’s more, he was modest and sweet-tempered and an excellent conversationalist.

And then there was John Jay, a foreign-policy expert who’d helped negotiate the Treaty of Paris after the war. He’d married Sarah Livingston, whom Alexander knew from his prep school days. Jay hadn’t attended the Constitutional Convention, but he was a former president of Congress and had worked on the constitution of New York state.

Alexander hoped his friend Gouverneur Morris would join them after his star turn in Independence Hall, but Morris was swamped with work. Another friend, William Duer, wrote pieces that didn’t suit.

Meanwhile, he and Washington swapped intelligence with each other on how the proposed Constitution was faring. Parts of Virginia were enthusiastic, Washington reported. “In Alexandria … and some of the adjacent Counties, it has been embraced with an enthusiastic warmth of which I had no conception. I expect notwithstanding, violent opposition will be given to it by some characters of weight & influence, in the State.”

Alexander found the same. “The constitution proposed has in this state warm friends and warm enemies…. The event cannot yet be foreseen. The inclosed is the first number of a series of papers to be written in its defence.”

FOR THE TRIO OF WRITERS, TIME WAS OF THE ESSENCE.

The enclosure was a newspaper clipping from October 27, 1787. It was the first in a series of written salvos his team had fired back at opponents to the new Constitution. It was based on an outline he’d drafted on board a sloop sailing up the North River on his way to his wife’s family in Albany.

“To the People of the State of New York,” he’d written.

He signed it “Publius,” meant to indicate he was a friend of the people.

Each of the Federalist essays began this way, and each was a letter of sorts: a mixture of love, invective, lectures, hopes, and fears for America. He threw himself into the task, juggling this with his law practice and growing family. Eliza had another baby on the way, conceived during one of his visits home from Philadelphia.

JOHN JAY ROUNDED OUT THE TEAM OF AUTHORS BEHIND THE FEDERALIST ESSAYS.

It was the perfect writing challenge for Alexander. He had an opposing force on which he could leverage his arguments—the antifederalists who wanted states to reign supreme. He dipped quills into oceans of ink, intending to drown these men in words. Just as he walked and talked to memorize his studies when he was a student, he paced around his study while conjuring his arguments in his head. And then he sat at his desk for six to seven hours at a time to write, fueled by strong coffee. He first took down the Articles of Confederation. Then he built up the document written to replace it. In just one week, he produced several essays on a subject close to his heart: taxation.

For the trio of writers, time was of the essence. The haste was partly to overwhelm opponents with words. But partly it was to beat the ratification process, which began in November.

Madison and Alexander, who wrote most of the letters, made something of an odd couple. Madison was much shorter than Alexander, whom no one ever called tall. Where Alexander loved parties and socializing and women, Madison was quiet and solitary. Where Alexander had, despite his busyness, managed to woo and marry during the clang of war, Madison would marry late. Where Alexander was stylish and meticulously groomed, Madison preferred simple black clothing.

They did have some things in common, and this helped them write so cohesively in the Federalist papers that some people couldn’t tell their writing apart. Both were realists about human flaws. “If men were angels, no government would be necessary,” Madison wrote.

Alexander always feared the excesses of the mob. This is where the devil emerged. The best safeguard against this was something he called “an aristocracy of merit”: people who were intelligent, honorable, and experienced.

A better word for this might have been meritocracy. After all, Alexander wasn’t an aristocrat by birth. He’d become one by effort. Any man could earn the same by giving as much. It was an earned aristocracy.

In all, amid the fullness of his life, he would write fifty-one of these essays. With Madison, he collaborated on three more. Madison took on twenty-six himself. Jay, who’d suffered ill health, managed to contribute five. In seven months, the three men wrote 175,000 words, which were eventually bound into two volumes totaling six hundred pages. It would become one of the most influential works of political philosophy and practical governing the world had ever seen.

Those who worried America would install a king and dissolve the separate states began watching him closely and collecting evidence that fit their paranoia. But Alexander never was a monarchist. And in Federalist No. 22, he wrote, “The fabric of American Empire out to rest on the solid basis of THE CONSENT OF THE PEOPLE.” It didn’t matter to some, though. Alexander made lifelong enemies as readily as he made lifelong friends.

IT WAS AN OPEN SECRET WHO’D WRITTEN IT.

He didn’t let it worry him. He had only one aim: to persuade his fellow New Yorkers to ratify the Constitution. Nine states had to ratify the document for it to take effect. In December 1787, Delaware, Pennsylvania, and New Jersey voted to accept the document. The next month brought approval from two more states: Georgia and Connecticut. Massachusetts squeaked an approval through in February. That made six.

By March, Alexander, Jay, and Madison had bound their first Federalist book. It was an open secret who’d written it. Alexander and Madison sent hundreds of copies to delegates in New York and Virginia, two large states that had not yet voted. After Madison traveled back to Virginia from New York, where he’d been working as a delegate, the two exchanged dozens of letters.

Alexander signed his affectionately. No one could ever replace Laurens’s spot in his heart. But he and Madison had become close allies who shared similar antipathy to slavery and a commitment to holding the union together with passionately reasoned principle. Alexander relished the connection.

Meanwhile, the clock ticked. Maryland ratified in April, followed by South Carolina in May. That made eight. North Carolina and Rhode Island seemed like lost causes. New Hampshire was a toss-up. It would come down to Virginia and New York, Madison’s and Alexander’s home states.

The vote in Virginia would happen two weeks before the vote in New York. Alexander knew he couldn’t beat Clinton and his faction by reason. The only hope was to use momentum from other states to bring New York into the fold. He kept in close contact with Madison, leaving nothing to chance.

“We think here that the situation of your State is critical,” he wrote on May 19. “Let me know what you now think of it. I believe you meet nearly at the time we do.”

He asked Madison to send word by express rider the moment things were decided. The stakes could not be higher. Without ratification, the nation could devolve into civil war.

Things looked grim in New York, despite Alexander’s best efforts. He was one of the state’s delegates, and his side was in the minority. Just nineteen federalists favored ratification. Clinton and his cronies had forty-six antifederalists.

New York’s convention began June 17 in Poughkeepsie. Alexander traveled there with John Jay and Robert Livingston, cheered on by the city’s merchants, who favored ratification and the way it would improve their business prospects. Once he arrived in Poughkeepsie, though, he was on hostile turf.

“Our adversaries greatly outnumber us,” he wrote to Madison on June 19.

Clinton was elected chairman of the convention, which took place in the city’s courthouse. Each clause of the Constitution would be debated point by point, as had happened during the Constitutional Convention. This rule was Alexander’s doing, and it was a clever gambit meant to buy enough time for results from Virginia to come in.

Things looked far from certain in the South. “I am very sorry to find by your letter of the 13th that your prospects are so critical,” Alexander wrote Madison on June 25. “Our chance of success here is infinitely slender, and none at all if you go wrong.”

As New York’s convention progressed, Alexander spoke dozens of times, once at such length that he had to sit down midspeech. That was on June 20. The next day, New Hampshire became the ninth state to ratify. The Constitution was now the governing document of the nation. But the fates of New York and Virginia still hung in the balance. Either could secede from the union.

The Clintonians shifted their tactics. They could not defeat the Constitution. But they could tie it up in strings—anything to preserve their power as a state.

The next week, on June 28, Alexander’s own words from the Constitutional Convention were used against him as he was trying to show how the states’ power would check federal overreach. John Lansing, who’d been there as one of New York’s three delegates, accused Alexander of talking out of both sides of his mouth when it came to the viability of the states’ power.

Alexander was incensed. The accusation was “improper and uncandid.”

Lansing fired back and asked Robert Yates, the third delegate, to show the notes he’d taken of the secret proceedings as proof. Yates pulled them out. The crowd erupted, and Clinton had to call them to order before they adjourned for the day.

When they met again on Monday, June 30, the debate continued—much in the way of a courtroom cross-examination, with both Alexander and Jay grilling Yates, who never did read his notes. Two days passed, and a rider galloped to the courthouse with a letter for Alexander. It was from James Madison: Virginia had ratified the Constitution. They’d done it! Madison had triumphed!

Reinvigorated, Alexander turned up the heat on New York until, one by one, the antifederalists came around. Tempers flared like rockets. On July 4, a fight broke out in Albany. A group of antifederalists attacked a larger group of federalists. One person was killed and eighteen wounded.

Others were ready to celebrate. On July 23, giddy New York City residents anticipating victory staged a rally. Five thousand merchants and tradesmen paraded down Broadway in the rain. Mixed in with the floats and banners were a ten-foot-long loaf of bread, a three-hundred-gallon barrel of ale, and old friends of Alexander Hamilton, including Robert Troup and Nicholas Cruger, who’d dressed as a farmer with a half-dozen oxen.

The best of all, though, was a twenty-seven-foot miniature frigate christened the Federal Ship Hamilton. It rolled through town on hidden wheels. A cart followed, carrying a banner proclaiming a message in rhyme as cannons blasted the end of the Articles of Confederation and the birth of the new Constitution:

BEHOLD THE FEDERAL SHIP OF FAME,

THE HAMILTON WE CALL HER NAME;

TO EVERY CRAFT SHE GIVES EMPLOY,

SURE CARTMEN HAVE THEIR SHARE OF JOY.

The vote on July 26 was close, the closest in the nation, at thirty to twenty-seven. Alexander, against all odds, had won.

His next task, undertaken in September, was less daunting if no less vital. He had to persuade George Washington to do the last thing he wanted to do: leave his beloved farm behind and become the nation’s first president.

“BEHOLD THE FEDERAL SHIP OF FAME, THE HAMILTON WE CALL HER NAME!”