IT WOULDN’T DO ANY GOOD to set up a system of government without the right man leading the nation. Washington had managed to lead an unprepared, overmatched army to victory despite obstacles flying at him from every direction; he could do the same with the nation. No other man could.

Alexander sent him a copy of both volumes of The Federalist, along with a nudging letter. “I take it for granted, Sir, you have concluded to comply with what will no doubt be the general call of your country in relation to the new government.”

Washington wrote back. The work of Publius—he knew who the three authors were—would be a classic, he predicted, “because in it are candidly discussed the principles of freedom & the topics of government, which will be always interesting to mankind so long as they shall be connected in Civil Society.”

At the end of his letter, he addressed the awkward matter of his candidacy. For one thing, people might not want him to be president. For another, he needed to wait for more information to know whether it was the right thing. He also wasn’t sure he had the ambition for the job.

“I would not wish to conceal my prevailing sentiment from you,” Washington wrote. “For you know me well enough, my good Sir, to be persuaded that I am not guilty of affectation, when I tell you, it is my great and sole desire to live and die, in peace and retirement, on my own farm.”

Alexander, not a slow thinker like Washington, replied immediately. Washington needed to answer this call to duty. The system set up by the Constitution depended on Washington’s approval and leadership. If things went awry because the wrong man was in the office, people would blame the system and the men who’d created it. Only Washington could deliver the faith of the people and the necessary wisdom.

Washington sent an appreciative response a few days later. “I am particularly glad, in the present instance, you have dealt thus freely and like a friend…. I thought it best to maintain a guarded silence and to lack the counsel of my best friends.”

Washington remained humble but disclosed he would take the job for the good of the public, and then he would retire to his steady dream: “to pass an unclouded evening, after the stormy day of life, in the bosom of domestic tranquility.”

Modest as he was, Washington was no fool. If he was the key to bringing the Constitution to life, then those who opposed the Constitution would prefer a president who’d kill it. He anticipated challenging days ahead and signed the letter “with sentiments of sincere regard and esteem.”

The years had bent their bond. But they had not broken it.

ONCE THE GENERAL HAD BEEN PERSUADED TO run, Alexander left nothing to chance. If any other man should get the votes, Alexander predicted mayhem, and he wasn’t shy about saying so.

Alexander saw a defect in the new Constitution, and he worried that even as admired as Washington was, it would lead to the inadvertent election of antifederalist John Adams. Under the Constitution, the person who got the most votes in the Electoral College would be president, and the runner-up, vice president. If federalists and antifederalists were divided about Washington but agreed on Adams, Adams would get the most votes and the top job. This must not happen.

Alexander kept tabs on who the electors were and whom they were leaning toward. He concluded it would be prudent to siphon away a few of Adams’s votes, so he engaged in backroom politicking. In January 1789, he wrote to James Wilson, one of the few men who’d signed both the Declaration and Constitution, as well as friends in Connecticut, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania. He wanted a few people to throw away their votes, lowering Adams’s count.

“Your advices from the South will serve you as the best guide; but for God’s sake let not our zeal for a secondary object defeat or endanger a first.”

Alexander also wanted Clinton’s long reign as governor to end. So he campaigned for Robert Yates. Yes, the man had been an albatross around Alexander’s neck during New York’s ratifying convention, but he’d come around after the Constitution was ratified. Alexander’s attempts to muck with state politics backfired. Clinton was reelected. Then he dismantled the coalition Alexander was trying to build by appointing a close friend of Yates’s to the attorney general spot. That man was none other than Alexander’s courtroom rival Aaron Burr.

WASHINGTON WAS INAUGURATED ON THE BALCONY OF FEDERAL HALL, ON WALL STREET.

IN THE FIRST U.S. PRESIDENTIAL ELECTION, ON February 4, 1789, electors from ten states cast ballots. New York hadn’t put together its group, and North Carolina and Rhode Island still hadn’t ratified the Constitution. The ballots were to be unsealed and counted in March, but snowy weather in New York meant that not enough congressmen and senators could get to the capital until April 6.

The ballots were unsealed and tallied then, and the results were stunning: every single elector had cast one of his two ballots for George Washington. John Adams came in second place with thirty-four votes. John Jay came in third place with nine votes.

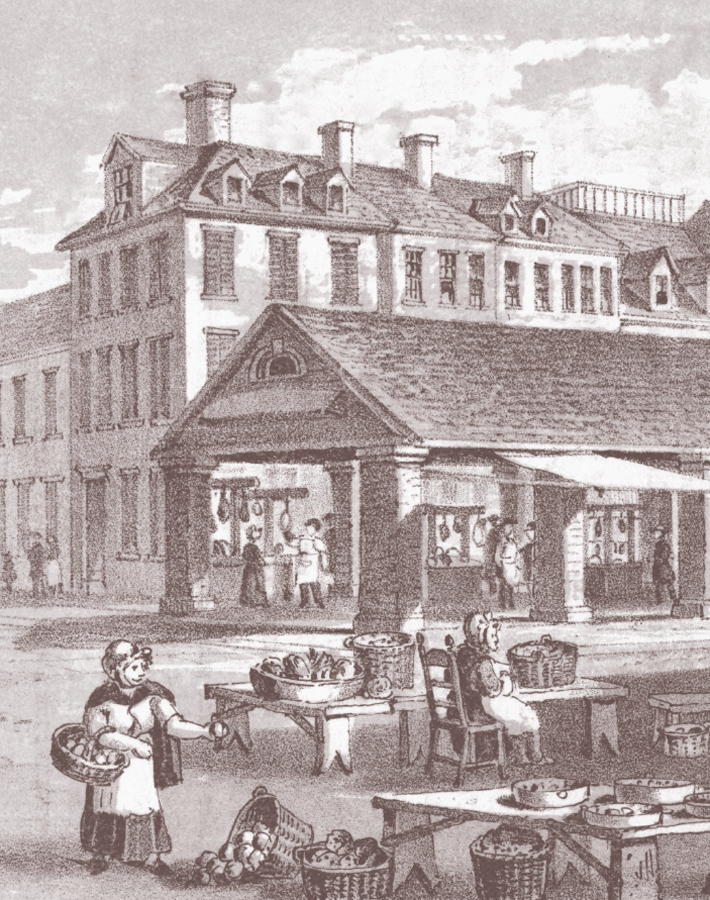

Washington, reluctant even with a unanimous victory, traveled from Virginia to New York, where he was met by Alexander’s political enemy Governor Clinton. They led a parade of soldiers and merchants through the city. The inauguration ceremony took place on the second-floor balcony of Federal Hall, a grand brick building with four stone columns holding up a pediment with an eagle. He wore a brown suit made of homespun cloth—to send a distinctly American message. The organizers, still finding their way, had forgotten a Bible, so Washington swore his oath on a thick and elegant one borrowed from a nearby Masonic lodge. His hands shook as he delivered an address, written by Madison, to both the House of Representatives and the Senate.

ORGANIZERS BORROWED A BIBLE FROM THE NEARBY MASONIC LODGE FOR THE CEREMONY.

Straightaway, Washington turned to Alexander for advice on how to manage the public aspects of the presidency. Taking cues from European protocol, Alexander specified how often Washington should receive visitors and for how long. He said the president should accept no invitations, and he should throw parties a few times a year on important anniversaries of the Revolutionary War. He gave Washington permission to keep his weekly get-togethers small and brief.

THE STALWART WASHINGTON BORE THE PAIN.

The goal wasn’t just keeping Washington’s nerves intact. It was to make sure he didn’t seem to show favoritism. Alexander wanted Washington to be happy and successful as he spun a new government from nothing. The nation wasn’t just a glossy weave of abstract ideas. It would be durable: woven from tiny details into a fabric unlike anything the world had ever seen.

Not every detail was as small as the politics of a homespun suit or the frequency and duration of dinner parties. One of the larger details Washington had to work out was his cabinet. The makeup of it hadn’t been specified in the Constitution.

Before Washington could officially round out his cabinet, though, he got sick. It was June. He lay in bed with a fever and a painful growth, caused by a bacterial infection, in his left thigh. A physician cut it out without anesthesia, and the stalwart Washington bore the pain. But he was perilously sick. Bedridden for six weeks, he could not sit up or attend the public Fourth of July celebration. But he’d already quietly offered Alexander a position in the cabinet as the nation’s first Treasury secretary. Thomas Jefferson would be secretary of state, and Henry Knox would be secretary of war.

Other men wanted the Treasury job, but Alexander came with a recommendation from Robert Morris, who had been in charge of finance during the Revolution.

Alexander gleefully accepted the challenge, though the $3,500 salary was far less than he made as a lawyer, and he and Eliza were supporting five children. Alexander turned his law practice over to Robert Troup. In early September, Washington officially established the Treasury Department, and on September 11, 1789, he appointed Alexander its head. The Senate confirmed the appointment immediately, and on the next day—a Saturday—Alexander set to work dragging the United States from the deep financial hole it had slid into. He arranged for a $50,000 loan from the bank he’d helped found in New York, then another the next day from the Bank of North America.

Congress passed a resolution on September 21, 1789, requesting that Alexander provide a full report on the nation’s financial state. They wanted the details in less than four months. In his Report Relative to a Provision for the Support of Public Credit on January 9, 1790, he revealed in great detail what the country owed for its liberty: $79 million. Some money was owed to other countries, and some to U.S. citizens. The states’ portion of the debt was $25 million; the rest belonged to the federal government. His report addressed how the debt would be paid and how the country would be able to take on additional debt in the future.

Alexander had a more sophisticated understanding of debt than most people at the time, who viewed it as an evil. The truth was, debt could sometimes be a useful and even necessary tool for a nation. The Revolutionary War was an example (as was the French and Indian War earlier). The Continental Congress had had no means of paying for the supplies, weapons, clothing, food, and salaries the war demanded, but they’d bet on the future fortunes of the nation that they would. There were also other reasons to go into debt. Without liquid capital—money that can be spent—an economy can’t grow to its full potential. This is true for individuals and for governments, merchants, and property owners. Strategic debt can revive a struggling economy.

When governments can borrow at a reasonable interest rate and generate the tax revenue to pay off the principal and interest of the loan, that activity boosts the economy in many ways. What’s more, states that pay their debts—just like people—earn the trust of their partners. Liberty depends on the integrity and security of property—this principle was utterly clear to Alexander.

Americans had been burned when it came to debt from the U.S. government, including soldiers who had been paid in government bonds. After the war, no one was sure if these IOU slips would be paid. Some soldiers, desperate for money, had even sold them for a fraction of their stated value. Others wagered that selling low was better than waiting for money that might never come. Speculators were happy to risk a few cents on the dollar for potential huge payout later.

Guaranteeing the value of those bonds would give people trust in the government and keep their value steady. There was one tricky aspect of this: what to do about the veterans who’d already sold theirs. Weren’t they owed something from the nation they’d fought to build?

Alexander argued against compensating veterans. For one thing, it would be nearly impossible to track down every man who’d sold his bonds to speculators, determine the rate, and make up the difference. What’s more, the ones who had sold out of desperation had chosen to bet against their own government. The speculators hadn’t. Therefore, people who’d taken the risk deserved the rewards. This argument became the keystone of the securities market in the United States. The risk is on the buyers and sellers to manage their choices without government interference.

LIBERTY DEPENDS ON THE INTEGRITY AND SECURITY OF PROPERTY.

Alexander made another controversial argument: the federal government should take responsibility for debt incurred by individual states, even when some states had already repaid their portion. He had two reasons: The Constitution permitted only the federal government to collect duties on imported goods, a major source of revenue. Also, one repayment scheme was better than as many as thirteen separate ones.

His plan proposed taking out a $12 million loan in the form of government securities to repay the wartime debt and interest. People who bought the securities could choose among several payment plans, and the interest rate would be favorable compared to rates in Europe.

As for paying back the debt, revenue had to be generated somehow, both for past and future interest. The first step was to establish a system for taxing imports. To manage this, he proposed a national customs service, which would receive duties from goods brought into the country from the nations exporting them.

ALEXANDER WAS NERVOUS ABOUT HIS REPORT.

For revenue generated from American citizens, Alexander flagged items like tea, coffee, and alcohol. These might be luxuries, but people liked to indulge, so he anticipated it would be a relatively stable source of funds. And if people stopped drinking as much? All the better for their health.

Alexander was nervous about his report. The night before it was read to Congress, he wrote to Angelica. He’d seen Eliza’s sister again during Washington’s inauguration, but she had to return to England to take care of her children, and he missed her. They’d exchanged several letters in the interim, flirting wildly with each other as always. But this note was largely about his anxiety.

“Tomorrow I open the budget & you may imagine that today I am very busy and not a little anxious. I could not however let the Packet sail without giving you a proof, that no degree of occupation can make me forget you.”

His fears were well placed. Some despised his report and its plans. What took him utterly by surprise, though, was the vehemence of opposition from his friend Madison, who’d supported his nomination as Treasury secretary. Yes, they’d had disagreements after their work together on The Federalist. Take the necessity of the Bill of Rights, for example. Alexander hadn’t thought the ten amendments to the Constitution were necessary, but Madison was adamant about protecting individual liberties in the face of a powerful federal government. Even so, the last thing Alexander expected was that this difference would widen into a chasm.

Madison rolled out the verbal artillery against Alexander’s plan with the IOUs on February 11, 1790. Madison thought speculators who’d bought the now-valuable public debt weren’t morally entitled to the profits. It was meant for the original holders, who’d only sold out of desperation. What’s more, he viewed public debt not as the blessing Alexander described, but as a curse.

Madison’s argument didn’t win the day, but the loss of the alliance crushed Alexander. They’d worked hard, inspired brilliance in each other, and jointly written a political masterpiece. There had been such warmth in their letters. Not as much as in the ones he’d exchanged with Ned Stevens, Lafayette, and especially John Laurens. But still the bond was there. He’d cherished it. And then it vanished.

Growing in its place was something hard and bitter, a division between federalists and antifederalists, echoed in the ever-widening rift between the North and South. The North would follow Alexander’s plan and diversify its economy with manufacturing, banks, stocks, and bonds, while the South would continue to rely on the labor of enslaved people. The great irony was that the South and its antifederalists claimed their path was the one of liberty.

The next big fight was whether the federal government would assume the states’ individual debts. States that had paid their debts opposed assumption. Alexander and Washington favored it. After all, every state benefited from the war, and some had suffered more than others. By spring, Washington was ill again, and Alexander had to campaign for assumption on his own. He had a rough go of it, and on April 12, the House rejected it by a two-vote margin.

It spelled disaster. What’s more, Alexander’s political foes turned on him in pointed ways, especially Aedanus Burke, a silver-haired, eagle-nosed representative from John Laurens’s state of South Carolina. Burke had been offended back in July when Alexander gave a eulogy for Nathanael Greene, who’d died on his Georgia plantation in 1786.

Alexander had called Greene “a general without an army—aided or rather embarrassed by small fugitive bodies of volunteer militia, the mimicry of soldiership!” The line was meant to highlight what Greene had accomplished with an ill-equipped militia against well-trained professional soldiers. It mortified Burke.

He stewed over this characterization and unleashed it on Alexander in March on the floor of the House. He called Alexander a liar, a blow to his always vulnerable honor. When Alexander heard about Burke’s charge, he penned the first salvo of a duel, telling Burke he’d misinterpreted the eulogy.

Burke fired off a nearly immediate reply. “The attack which I conceived you made on the southern Militia, was, in my opinion a most unprovoked and cruel one…. You may have forgot it, but some of your Friends and all your acquaintances have not forgot it…. Thus I have very candidly, in this disagreeable business explained my feelings and motives.” His last line was ominous, saying that men “of Sensibility and honor” would approve of his conduct.

AEDANUS BURKE ACCUSED ALEXANDER OF MAKING A CRUEL ATTACK ON SOUTHERN SOLDIERS.

That word choice was provocative. More letters were exchanged in accordance with the rules for affairs of honor. Resolving the matter without bloodshed required intervention from several congressmen. And in it, Alexander revealed his fatal flaw: a willingness to throw away everything he had—his wife, his home, his children, his ascending career, and even his own life—for the sake of his reputation.

He wasn’t just tempting death. He was actively inviting it to visit. It was romantic. It was daring. But it did nothing to solve the pressing problem at hand: how to get support for a federal assumption of the states’ debt.

Not far from Alexander’s residence at 57 Wall Street, Thomas Jefferson had rented a home of his own once he’d returned from Paris to become secretary of state. Accompanied by his enslaved chef, James Hemings, who’d had culinary training in Paris, Jefferson had moved to New York in March 1790, after Alexander’s initial report was delivered. Like Madison, Jefferson hated it and the idea of assumption. But this issue wasn’t the only big one stalled in Congress. The other: where the federal government should have its permanent home.

ALEXANDER LOOKED “SOMBRE, HAGGARD, AND DEJECTED BEYOND COMPARISON.”

Alexander wanted New York, the temporary home of Congress, to have the honor. Then, like London and Paris, New York would be both a financial and political hub. Southerners like Jefferson and Madison disagreed. Not only was New York far from their states, it was also distinctly urban—the opposite of the agricultural South. Congress was stymied. By June, it looked as though the plan for assumption was doomed as well.

Alexander, frustrated to the point of wanting to quit, ran into Jefferson outside Washington’s office. In his journal, Jefferson wrote that Alexander looked “sombre, haggard, and dejected beyond comparison.” Sensing an opportunity, Jefferson invited him to a dinner at his house to talk it over with Madison.

At the Sunday, June 20, dinner, which also included Tench Coxe from the Treasury, it became clear that Madison and Jefferson were in the mood to make a deal to wrap up the many conversations they’d had on the topic. If Alexander would agree to make a few changes to his debt plan and place the nation’s capital in the South, they would agree to drum up votes on behalf of assumption.

JEFFERSON AND ALEXANDER MADE THE DEAL THAT TURNED WASHINGTON, D.C., INTO THE NATION’S CAPITAL IN A HOUSE ON MAIDEN LANE IN NEW YORK.

The dining-room deal was struck, and by the end of summer, the votes had been cast. The federal government would assume the debt, ensuring the enactment of Alexander’s vision for the nation’s finances. And the capital would be in the South, on the banks of the Potomac and Anacostia Rivers. Land that had been taken from the Algonquian-speaking Nacotchtank tribe after they’d been decimated by European diseases would now be given up by Maryland and Virginia. It would take years to design and build the new capital. In the interim, the government would leave New York and move to Philadelphia.

The summer of 1790 was busy. Not only did Alexander work out the compromise with Jefferson and Madison, but he also noticed that tax collectors in the Customs Department were bringing in suspiciously low revenues. Based on his experience as a shipping clerk, he suspected smugglers.

MADISON AND JEFFERSON HATED THE PROPOSAL.

In response, Congress passed the Tariff Act, which established a ten-ship fleet of revenue cutters, working under the Treasury Department to enforce import duties. (Alexander had found time the year before to research ships, their construction, and the makeup and salary requirements of their crews; the fleet was the forerunner of the U.S. Coast Guard.) As head of the Treasury, he was also managing a growing system of lighthouses, beacons, buoys, and piers, dealing with employees who thought they weren’t getting paid enough, and continuing to wrestle the constitutional intricacies of paying soldiers for their service in the war.

By the end of that year, however, his work was beginning to pay off. Not only had Alexander saved the nation from bankruptcy, but the government had generated a revenue surplus. This didn’t mean he could let up; the next step was to begin repaying the debt of the states, which would require direct taxation on whiskey.

What’s more, there were complications with England and France. Although France had been an ally during the war, the trade terms with England were better for America, and this commerce brought in three-quarters of the Treasury Department’s revenue. France also was in the midst of a revolution of its own, which meant it was no longer the same government that had been allied with the states.

Alexander didn’t let up for a minute, and on December 15, he made his most controversial proposal yet: to found a Bank of the United States. The Constitution said nothing about banks, and this would become an issue with his opponents. But the country needed one. The nation’s finances were so haphazard that some debt payments from the states had been made in Spanish dollars and tobacco receipts.

He’d been pondering a national bank for years. It would do much for the nation. Not only would a bank give America a uniform currency, but it would also provide the credit that businesses needed to grow. The government could take loans and hold deposits, too.

He’d locate it in Philadelphia, a good choice because it was a big city with lots of business activity. And he’d need $10 million to get the wagon rolling, $8 million of which would come from private investors, with the last $2 million being the government’s share. He’d long thought a mix of public and private funding made sense.

Madison and Jefferson hated the proposal, which passed in the House of Representatives anyway in February 1791. The vote was lopsided, with the urban North heavily in favor and the agricultural South staunchly opposed. Jefferson even sniped to Madison that the idea was treasonous—essentially saying anybody who so much as worked as a bank teller should be put to death for it.

The crux of their objections: it was unconstitutional for the nation to form a bank because the Constitution hadn’t given the federal government this power explicitly. Madison hadn’t always thought this way. In fact, Federalist No. 44, which he wrote, said, “No axiom is more clearly established in law, or in reason, than wherever the end is required, the means are authorised; wherever a general power to do a thing is given, every particular power for doing it, is included.”

There wouldn’t be any more dinner parties at Jefferson’s house. Madison and Jefferson were united in bitter rivalry with Alexander. Madison wanted Washington to use the presidential veto power for the first time. Washington gathered opinions from Jefferson and his attorney general, Edmund Randolph, the author of the Virginia plan. They opposed the national bank.

When Washington asked Alexander for his opinion of Jefferson’s and Randolph’s arguments, Alexander rubbed his hands together, rolled up his sleeves, and went to work.

In a matter of days, he’d written a short book on the topic, staying up all night to meet the president’s deadline. Eliza worked through the wee hours with him, copying his writing. When he walked out the door the next morning, he delivered the document to Washington. He’d demolished Jefferson’s and Randolph’s arguments, and Washington signed the bill.

With that, Alexander Hamilton had created a bank.

In the meantime, he’d also written a Report on the Establishment of a Mint that contained a plan for creating and managing coins of varying denominations that would be useful and accessible to the rich and to the poor. By July 1791, the public had an opportunity to buy stock in Alexander’s bank. The venture was wildly successful, selling out much more quickly than the week he’d anticipated. Madison and Jefferson muttered about a den of corruption, a place where “stock-jobbers” gambled their morality away instead of putting in an honest day’s work. So feverish was the buying and selling of bank stock scrip that in August, prices expanded into a bubble. Alexander instinctively had the government buy up some shares to ease the pain of the pop.

AROUND THE SAME TIME, ANOTHER MATTER OF money—this time, a pocketful of bills—would occupy Alexander’s time. Like his rivalry with Jefferson and Madison, it would grow to ruinous proportions.

It all started with a knock on the door at his home in Philadelphia.

A woman stood before him. She had dark eyes and pale skin and a cloud of curls around her heart-shaped face. She was young. She was beautiful. She was in trouble. Alexander couldn’t resist her. He told her that she’d come at a difficult time for him—Eliza and the children were still home—but that he’d visit her that night, bringing a small supply of money.

Much to his regret, he did.