USE

The “Thumper” goes to war

THE TACTICAL EMPLOYMENT OF GRENADE LAUNCHERS

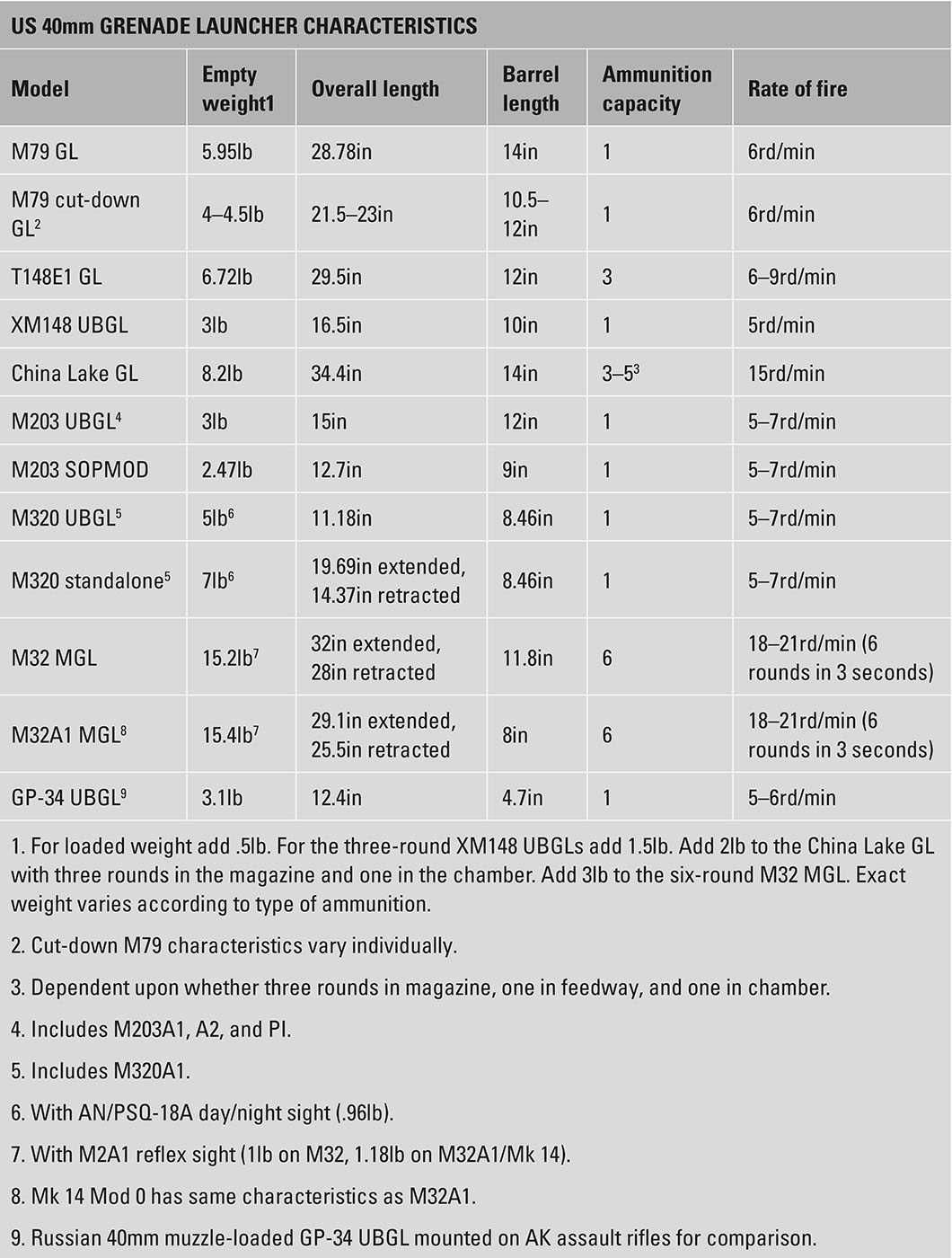

40mm GLs are effective weapons up to 200m (219yd) for point targets and 375m (410yd) for area targets. They provide the rifle squad and platoon with a valuable, flexible, agilely moved fire-support weapon in offensive and defensive operations against a wide variety of targets as well as signaling and marking.

Manning and allocation

Since 1961 the US Army has allotted two grenadier-manned GLs to rifle squads, thus providing one grenadier for each of the two fire teams with the rank of specialist 4 (equivalent to corporal). During the M79’s development it was considered that the two sergeant fire-team leaders be armed with M79s instead of M14s. Fortunately, it was decided that team leaders had too much to do in addition to operating an M79, and dedicated grenadiers were designated. From 1958 to the present day, US Army rifle squads have consisted of 9–11 men: the staff sergeant squad leader and two four or five-man fire teams (Alpha, Bravo).

Since 1944, the US Marine Corps has employed a rifle squad with three corporal-led, four-man fire teams (Nos 1, 2, and 3) plus the sergeant squad leader. When the M79 was fielded in 1962 a 14th Marine, a lance corporal (equivalent to Army PFC) grenadier, was added to the squad. One GL per fire team was desired, but the Marines were not willing to lose three of the squad’s 13 rifles. When the M203 was fielded in 1972, the 14th man was deleted and the three fire-team leaders armed with M203s, the logic being that they would mark targets with the GLs. In many units, however, a rifleman in each team became a grenadier as team leaders were busy enough.

Owing to the XM148 UBGL’s many flaws it only saw approximately nine months’ service during 1967 with selected units in Vietnam. It is seldom seen in period photographs. The XM148s were withdrawn and M79s returned to the units prior to the February 1968 Tet Offensive. Here, an XM148 is attached to an M16A1 rifle using the special upper handguard. The L-shaped cocking lever can be seen forward of the 20-round magazine. The tilting bar sight has been removed here from the rear left side of the barrel above the GL’s pistol grip, a common practice. (US Army)

In both the US Army and the US Marine Corps, grenadiers were armed with an M79 and a.45-caliber Colt M1911A1 pistol with three seven-round magazines. (11B (US Army) and 0311 (USMC) were the military occupation specialties for infantrymen in general. There is no specific code for grenadiers; they are infantrymen with specialty GL training.) It was not uncommon for grenadiers to carry an M16A1 rifle in lieu of the pistol to increase the squad’s firepower. Some did not carry a pistol and others carried both a rifle and pistol. There were situations and terrain in which the grenadier could not always effectively or necessarily employ the GL, but the pistol was strictly a last-resort personal-defense weapon contributing nothing to the squad’s offensive firepower. M16-armed grenadiers would carry fewer magazines than riflemen. As squads were generally understrength, the Marine squad’s grenadier was part of a fire team rather than being a separate grenadier. Also, grenadiers with the M203 or M320 UBGLs carry fewer rifle/carbine magazines as the grenadier’s shoulder weapon is secondary. Even with an arming/safe range of 14–17m (46–56ft), grenadiers know they can fire an HE round or other types against personnel at closer ranges with devastating effect without the round detonating. Buckshot rounds were developed for this purpose. Of course, the comparatively slow rate of fire makes this impractical for self-defense in anything other than emergency circumstances.

A squad grenadier of the 3d Marines, 3d Marine Division on Hill 861 northwest of Khe Sanh Combat Base in April 1967, before the epic battle commenced in which Hill 861 served as an important outpost for the main base. Until the rifle-mounted M203 grenade launcher was fielded in 1972, the US Marine Corps had only one grenadier per squad. With the introduction of the M203, the Marines went to three grenadiers per squad. In his left hand he holds a 3.5in M28A2 HEAT rocket for a 3.5in M20A1B1 rocket launcher or bazooka. (Bettmann)

Grenade launchers and squad automatic weapons

Since World War I most of the world’s rifle squads have had at least one light machine gun, a concept introduced by the French. From the end of the Korean War the US Army has had two LMGs per squad and the US Marine Corps three since 1944. With the fielding of the M14 rifle in 1959, the M1918A2 BAR was replaced by the M14 “automatic rifle,” a standard M14 with a bipod and the selector lock removed. It performed poorly and so the US Army fielded the M14E2 in 1963; this was redesignated M14A1 in 1966. It spite of its modifications, however, it too was a poor automatic rifle owing to inaccuracy, overheating, and limited feed capacity. The US Marine Corps did not adopt the M14A1. With the fielding of the 5.56mm M16A1 rifle through the mid-1960s, first in Vietnam and then Army- and Corps-wide, there was no LMG. Rifle platoons relied on their two 7.62mm M60 machine guns for automatic fire support up to 800–1,000m (875–1,094yd). Some units grouped one or two GLs with each M60 as a fire-support team.

An ARVN Ranger on the outskirts of Saigon in 1968. Many Vietnamese made very effective grenadiers. The Ranger next to the grenadier is armed with a 7.62mm M14A1 (formerly M14E2) automatic rifle while the rest of the troops have M16A1 rifles. The ARVN received very few M14A1s. (Tom Laemlein/Armor Plate Press)

A “statement of need” for a squad LMG was released in 1972, and the 5.56mm M249 SAW began to be fielded in the mid-1980s and into the 1990s. The Army allotted two per squad and the Marines three. The Marines partly replaced the M249 with the Heckler & Koch HK416-based 5.56mm M27 Infantry Automatic Rifle beginning in 2011. The Army retained the M249, two to a squad, and replaced the two M203s with M320s.

A US Marine Corps M14 automatic rifleman marks targets for the squad’s grenadier. Conversely, the automatic rifleman could engage any enemy flushed out by exploding grenades. Marine Corps platoons were somewhat handicapped, having only three M79s compared to the US Army’s six. With the introduction of the M203 immediately after the Vietnam War, the Marine Corps tripled the number of grenade launchers in their rifle and reconnaissance platoons, going from three to nine. (US Marine Corps)

The pairing of GLs and the SAWs in the rifle squad provides a wider selection in terms of fire-support capabilities. In Vietnam when the Marines had only one GL in the squad, if engaging a small element, two fire teams and the grenadier laid down a base of fire while a third fire team maneuvered against a flank. The LMGs are realistically effective at 600–800m (656–875yd) against point and small area targets. Their ability to maintain sustained fire depends on their feed, 20- and 30-round magazines being inadequate compared to belt-fed. The GLs provide HE direct fire at point targets from within hand-grenade range (30–40m; 33–44yd) to 150m (164yd), and indirect fire against area targets up to 375m (410yd). Seldom does a squad need to engage more distant targets. It is roughly calculated that the squad’s two or three GLs provide one-third of its firepower, its two or three LMGs another third, and the 5–7 rifles/carbines the other third from pointblank to 550m (601yd) – 400–450m (437–492yd) being more realistic.

A US Marine assigned to 3d Battalion, 3d Marines, 3d Marine Division on Okinawa fires an M16A2 with an M203 UBGL and using his rucksack as a support. In the background a 5.56mm M249 light machine gun is fired from its bipod. M203s and M249s are often paired in fire teams to work together. (US Marine Corps)

GLs are issued to other units, with most headquarters and support units having a small number for self-defense. In a four-company (three companies prior to 1967) US infantry battalion in Vietnam there were 72 GLs in the 36 rifle squads, another one in each company HQ, and a half-dozen or so in both the battalion headquarters and company support companies.

M79 NICKNAMES

The M79 grenade launcher received numerous nicknames in Vietnam, as stated by one anonymous soldier in 1968:

They made a “Thump” sound when you dropped a round in the chamber.

They made a “Thump” sound a little distance away from them when you shot them.

They only “Thumped” your shoulder when you shot them with very little recoil.

And they sure as heck “Thumped” whatever you shot with them pretty good enough!

The Americans gave it nicknames relating to its distinctive report, a faint pop: “blooper” or “bluper,” “bloop tube,” or “blooker.” “Thumper” and “thump gun” were derived from its firing report and distant impact. “Burp-gun” (again for the sound, not because of any similarity with the M3A1 SMG), “elephant gun,” and “chucker” were less used. The cut-down M79 was simply called a “shortened (or short) M79” or “sawed-off M79.” Today, still in limited use by SOF, it is called a “pirate gun,” especially by SEALs, its nickname derived from the short, bell-mouthed blunderbuss or the swivel gun – a small, stubby cannon mounted on ships’ rails to repel boarders.

The projectile – “blooper ball,” “egg,” or “golf ball” – traveling downrange in a low arc looked like a 1.68in-diameter golf ball and traveled at about the same speed. The muzzle velocity of a 40mm HE round is 247ft/sec. Golf association governing bodies rule the velocity of golf balls will not exceed 250ft/sec, but most ball flights are slower.

Once standardized it was called the “M-Seventy-Nine” or simply the “Seventy-Nine,” but rarely as the “Mike-Seven-Niner” using the military communications phonetic letter and number pronunciation, though the cartridges might be call “40 Mike-Mike.” A media publicity tag called it the “platoon or squad leader’s artillery.” “Blooper” might also refer to the grenadier himself as would a “bloop gunner,” i.e. one who “ran a blooper” (or other M79 nickname).

Australians tagged the M79 according to its short-barreled shotgun appearance: “shottie” (shotgun), “sawnoff” (sawed-off shotgun), or “wombat gun.” The latter nickname might be because of the M79’s stubby rotund appearance not unlike this slow-moving, docile marsupial. (“WOMBAT” was also the nickname of the British 120mm L6 recoilless rifle used by Australia – “Weapon Of Magnesium, Battalion, Anti-Tank.”) The British Army made limited use of the M79 in Northern Ireland and the Falklands and some units called it a “dunk gun,” because of the firing report, or “spud gun” owing to the projectile looking like a hand-thrown potato. The British also used baton ammunition, aka “rubber bullets,” and referred to M79s in this role as “baton guns.” Post-Vietnam, New Zealanders called grenadiers “headhunters,” their tactical hand signal for grenadiers being a fist with fore- and little fingers extended.

The Vietnamese formally refer to the M79 as the súng phóng lựu M79-VN (grenade launcher M79-Vietnam), simply the súng M79 (launcher or rifle M79), or Em bảy chin (M-seven-nine). In Spanish-speaking countries it is known as la escopeta lanzagranadas M79 (the shotgun grenade launcher M79) or simply as em-setenta y nueve (M-seventy-nine).

The M203 and M320 GLs lack imaginative nicknames, being known simply as the “M-Two-Oh-Three” and “M-Three-Twenty” – the “M” might be dropped. However, the M203, M320, and M32 have on rare occasions been called “thumpers.” The M32 Multiple Grenade Launcher is occasionally referred to as the “M-G-L” and less so as the “Milkor” after the South African developer. It is occasionally referred to as the “six-pack” (mainly by the media) owing to its six-round cylinder. The SOCOM version is simply the “Mark 14.”

SEAL ambush, Vietnam 1970

The US Navy SEALs in Vietnam deployed on approximately six-month temporary duty tours. SEAL teams ONE and TWO deployed up to five 12-man platoons, each with two six-man squads. They conducted short-duration reconnaissance, hit-and-run raids, intelligence collection, and ambush missions using platoons and squads. Weaponry was left largely up to individuals, but the squad or platoon leaders could direct specific weapons be taken dependent on the mission. The terrain, expected ranges, and types of targets also dictated the armament. Attacking a small Local Force VC base camp with “spider holes” and bunkers called for different weapons than when executing a canal ambush against a sampan. The SEAL to the right is armed with a China Lake pump-action grenade launcher that could be loaded with 3–5 rounds, although four rounds was common. It weighed slightly over 8lb empty, about the same as an M14 rifle. The multiple-shot grenade launcher was valued for its rapid-fire ability to lob four aimed rounds in 5–6 seconds – especially valuable when attacking wooden sampans exposed on canals and rivers. A 40mm HE round striking water instantaneously detonated with most of the blast reflected from the surface and most fragmentation blown outward. A near-miss on a sampan was devastating. Owing to the China Lake’s slide-action it was easy for mud, water, and vegetation debris to enter the action and firing mechanism. This, coupled with its inherent fragility, made the weapon vulnerable to jamming and breakdown. The China Lake being non-standard, spare parts were not available and some of the few weapons available were cannibalized for parts. SEAL platoons rotating out of Vietnam transferred their China Lake GLs to the relieving platoons. Besides 40mm bandoleers, ammunition pouches, canteen covers, and Claymore bags, the SEALS used the grenade-carrying vest with 24 grenade pockets from late 1968. The back closure with adjustable tie-tapes securing the ventilating nylon-mesh back panels is obvious. The M79 grenade launcher (right) was used alongside the China Lake (left) owing to the M79’s reliability and slightly better accuracy at longer ranges. The M79 grenadier carries a non-standard .45-caliber MAC-10 submachine gun with 30-round magazine. Grenade launchers were used in conjunction with automatic weapons with good results. The SEALS also favored the 5.56mm Stoner 63A Commando light machine gun, known to the US Navy as the Mk 23 Mod 0. It was popular owing to its various types of belt-fed, large-capacity magazines (here a 150-round belt drum) and light empty weight of 12lb, almost half the weight of the 7.62mm M60, which the SEALs also used because of its longer range and better penetration.

Squad grenade-launcher tactics and techniques

Squad tactics and techniques are similar regardless of the GL models, although the improved accuracy of laser rangefinders and the rapid multishot capability of the M32 have resulted in more flexible use.

The first tactics manual incorporating the M79 was FM 7-15, Rifle Platoon and Squads, Infantry, Airborne, and Mechanized (March 1965). Other than training exercises, there were no real opportunities for lessons learned and new techniques to evolve. Units deploying to Vietnam had not even received the manual. There was barely mention of grenadiers in regards to control, suitable targets, positioning within movement formations, or incorporation into fire plans. In movement formation diagrams, grenadiers were shown in no particular position. Over the years lessons were learned and techniques developed along with new types of ammunition to expand the GL’s value. Squad leaders handle most of the controlling. Fire-team leaders lead by example: when he advances the team advances, when he hits the ground and opens fire so does his team.

The FM 7-15 manual did provide the following guidance, which still applies:

The squad leader assigned the exact firing position and sectors of fire for the grenadiers, if not previously selected by the platoon leader. The sector should be the squad sector or large enough to overlap the sectors of adjacent grenadiers. The GL is used as a direct fire weapon at ranges up to 350 meters [383yd] against crew-served weapons and grouped personnel. Grenadiers will cover the areas of dead space in the final protective fires of other weapons (MGs [machine guns], ARs [assault rifles]) and engage other appropriate targets.

For the most effective control, most team leaders position grenadiers adjacent to them to direct their fire whether moving or static. It was learned that a grenadier should not be a pointman. If hit it may be difficult to recover the GL under fire. In column formation the foremost grenadier, at least two men from the point, covers the front and one flank while the rearmost covers the other flank and rear. If engaged from a flank, both grenadiers return fire. Small patrols with one grenadier might position him near the rear to fire over the patrol as the lead men withdraw during a break-contact immediate-action drill. In assault line formations the grenadiers are usually positioned adjacent to the team leader. Team leaders are normally collocated in an automatic-weapon or GL position, whichever covers the most likely avenue of enemy approach, and their teams are assigned a sector of fire.

Wearing a DH-132A combat vehicle crewman’s helmet, this M113A1 armored personnel carrier driver of 1st Brigade, 5th Infantry Division (Mechanized) prepares to fire an M79 GL at about as steep an angle as safely possible, though highly inaccurate. He is probably dropping rounds into brush-covered areas to flush out any ambushers concealed in the Rome-plow cleared area bordering both sides of a highway – reconnaissance by fire. (Tom Laemlein/Armor Plate Press)

However, it is more important for the GLs to be positioned where both can cover as much of the squad’s sector as possible and overlap fires with adjacent squads. Squads on platoon flanks will cover gaps between adjacent platoons with GLs and LMGs.

This M79-armed grenadier of the 1st Infantry Division near the Saigon River in 1966 has as a secondary weapon in the form of a 12-gauge pump-action riot shotgun. Various models were issued with 20in barrels and five- or six-round tubular magazines. Most production M79 barrels had an OD-shaded anodized finish. (Tom Laemlein/Armor Plate Press)

GLs can be employed to cover dead spaces with indirect fire that cannot be placed under line-of-sight observation or direct small-arms fire. This requires an experienced “blooper gunner.” The GLs are pre-registered to fire on specific targets and aiming stakes are set for night aim at these targets. Likely concealed avenues of approach for the enemy can be rigged with surface trip flares or trip-wired Claymore mines (“mousetraps”) and when activated pre-planned GLs can fire into the area.

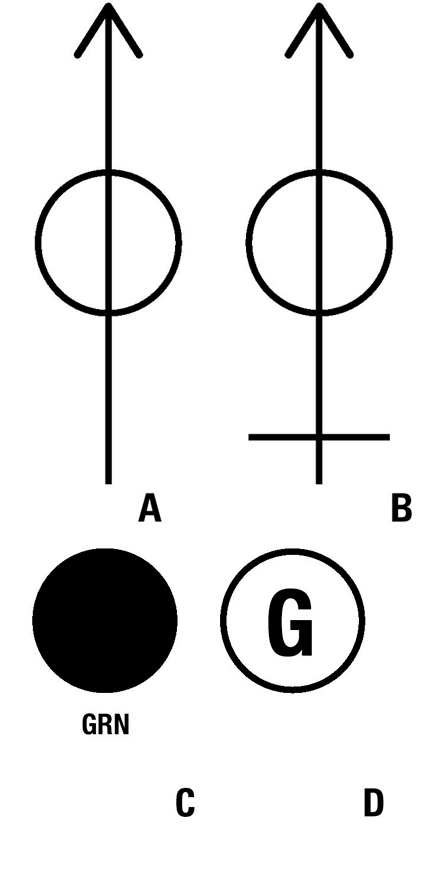

Blue or black (for friendly) tactical map symbols for 40mm UBGLs or standalone GLs are comprised of an arrow (indicating a direct-fire small arm) augmented by a circle to indicate a UBGL or standalone GL (A). A 40mm machine gun uses the same symbol with the addition of a short horizontal bar partway between the circle and the lower end of the bar (B). Grenadiers are indicated in tactical movement formation diagrams by a solid dot with “GRN” below it (C) or a circle-enclosed “G” (D).

Turning to matters of control, initially, the GL was considered just another individual weapon. It was not until experiencing combat that it was learned the grenadier may not detect all suitable targets. Leaders and other squad members should alert him to targets. The team leader or squad leader can direct the grenadier as to which targets to engage and might use the GL to mark targets for the rest of the squad with HE or smoke. Grenadiers, though, do not wait for orders to fire. They immediately engage targets they detect.

Squad leaders can task organize as necessary, one example being a maneuver element of riflemen and a fire-support element with one or two LMGs and two grenadiers. In Vietnam some platoon leaders grouped 4–6 grenadiers into temporary teams to lay down suppressive fire, blast suspected positions, and engage snipers.

In Vietnam, platoon leaders sometimes concentrated three to six grenadiers into temporary teams to provide covering fire for maneuvering riflemen or to suppress suspected enemy positions. They were especially effective against non-positively identified sniper positions. Here four grenadiers of 2d Battalion, 35th Infantry, 4th Infantry Division lay down suppressive fire with M79s in 1967. (Tom Laemlein/Armor Plate Press)

Ambush and reconnaissance: GLs make poor ambush-initiation weapons. If ambushing vehicles, engine noise may muffle the firing signature. Ambushers should not have to wait for the GL round’s impact as a signal to open fire. GLs are effective ambush weapons because of their ability to deliver HE rounds at ranges greater than that of a hand grenade, and can pursue fleeing enemy with fire. GLs can also be used for reconnaissance by fire, i.e., firing on suspected enemy positions to invoke return fire or cause them to withdraw.

Urban combat: The M79’s first urban combat in Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic taught valuable lessons that had never reached the training manuals. The 82d Airborne Division found that HE rounds detonated outside of window coverings (glass, shutters, louvers, Venetian blinds, screens, wire mesh, heavy curtains) and that little blast and fragmentation entered the room. Unless an enemy soldier was very close to the window, he would often escape injury. The round’s detonation simply alerted the enemy to depart immediately. When an enemy’s presence was detected, a squad’s two grenadiers immediately aimed at the window. One was designated to fire first and the second to fire immediately upon hearing the first’s “thump.” The first round blew away window coverings and the second entered the room through the opening to detonate inside against a wall or ceiling. HEDP rounds will penetrate any common window covering and blow some blast and secondary fragmentation into the room in a narrow cone, but most fragmentation will be expended outside and what little penetrates will only cause casualties directly in its narrow path. Using GLs within buildings and fortifications is ill-advised owing to fragments penetrating interior walls and blast reflecting down hallways, but mainly because the 14–27m (46–89ft) arming range makes it impractical within close quarters. The buckshot round can be used to shatter door hinges and for self-defense.

US Marines in Operation Enduring Freedom

The US Marine Corps adopted the M203 UBGL at the end of the Vietnam War with one assigned to each of a rifle squad’s three fire teams (Nos 1, 2, and 3). The M203 has been mounted on the M16A1, M16A2, and M16A4 rifles and the M4 and M4A1 carbines by the Corps. Today the 13-man Marine rifle and divisional reconnaissance squads are armed with ten M4 carbines, three M249 light machine guns and/or M27 Infantry Automatic Rifles, and three M203A1 UBGLs, and can be augmented by one or two M32A1 MGLs, making it arguably the most heavily armed rifle squad in the world. While the US Army began replacing the M203 UBGL in 2009 with the more sophisticated M320 GLM (see pages 64–65), the Corps is retaining the proven reliable, simpler, and lower costing M203. This M203A1 mounted on an M4 carbine has a clip-on forward handgrip. The squad with three M203 GLs can pump out approximately 18 aimed 40mm rounds per minute and maintain that rate of fire for several minutes. That rate could be doubled by the augmentation of the six-round M32A1. Of course it is seldom the case that such a high rate of fire is necessary. The benefit of having squad members armed with GLs is that they can immediately engage rapidly emerging targets such as fighting positions, window firing positions, crew-served weapons, suspected enemy positions, and small groups of exposed troops without having to request and coordinate fire support from 83mm Mk 153 Mod 1 Shoulder-launched Multipurpose Assault Weapons (SMAW) or 60mm M224 mortars. The Marines fielded a small number of M32 MGLs in 2006 for combat testing in Afghanistan and Iraq. Deemed successful and adding a great deal of firepower to the squad, the M32A1 – shorter-barreled (8in), but achieving the same range as the longer-barreled (11.8in) M32 – was adopted in 2008. A slightly modified version of the M32A1, the Mk 14 Mod 0 MGL, was adopted by US SOCOM for use by Special Forces, Rangers, SEALs, Air Force Special Operations, and other SOF in 2009. SOCOM has the authority to requisition its own weapons, but that does not mean all component organizations necessarily use those weapons and may use others. 40mm rounds are carried on MOLLE and ILBE by “velcroing” one- and two-grenade pockets onto the web equipment in the numbers desired by the grenadier. Deeper two-round pockets are available for pyrotechnic rounds. Six-round bandoleers in which the cartridges are issued are also used and can be seen on the ground.

FIRING GRENADE LAUNCHERS

While the ammunition is the same and there are similarities between the different types, each model of GL has its own particularities and peculiarities.

A broken-open M79 GL, courtesy of Trey Moore. This photo reveals the foot-like ejector protruding from the lower portion of the barrel’s breech, the breech lock on top of the barrel, and the curved cocking lever below the barrel’s breech end. (Author)

GLs can be fired from the usual firing positions, some being more accommodating than others owing to the GL’s configuration, especially UBGLs because of the host weapon’s design. These positions include standing, kneeling, sitting, squatting, prone, and supported. The latter includes leaning against a support like a building wall, fence, tree, or the lip of a foxhole. In Iraq and Afghanistan, firing from moving vehicles is taught. Most GLs can be fired from the right or left shoulder, although the China Lake was best fired from the right owing to the ejection port’s location and the M320 from the right as the barrel pivots left for reloading. The recoil is moderate (the heavier the host weapon, the lighter the recoil) and is merely a sharp shove against the shoulder.

A US Army captain demonstrates loading an XM674 tear-gas (CS) cartridge (light-gray body) into an M79. The red band indicates CS (tear gas) and a light-brown band a low-velocity expelling charge. Almost 9in long, the cartridge cannot be loaded into XM148 and M203 GLs. There was also a similar XM675 red smoke cartridge (light-green body) employed for training in the use of the CS cartridge. A special four-cartridge bandoleer lies on the ground. (Tom Laemlein/Armor Plate Press)

M79 GL operation is extremely simple. It points nicely and naturally. The safety lever is slid back setting it on Safe. If wearing gloves or trigger-finger mittens, the trigger guard may be swung left or right by pressing a detent on the guard’s frontend. The barrel latch forward of the safety is pushed to the right, automatically setting it on Safe if not already set. The barrel is broken open by pulling down the forearm. A cartridge is chambered and the barrel closed by pushing up on the forearm. Alternatively, holding the stock’s pistol grip in one hand and with the other hand free of the forearm, the barrel can be closed by quickly snapping the wrist upward. Either way the barrel latch automatically locks.

To sight the M79, the range is visibly estimated and is set raising or lowering the bar by turning the elevation screw wheel. For close-range direct fire the leaf sight is in the folded-down position. The butt is placed firmly high on the shoulder. For mid-range fire at higher angles the butt is placed low in the hollow of the shoulder. For long-range indirect fire the butt is clamped under the arm. The rear-sight notch, front-sight blade, and the target are aligned. Indirect fire is also achieved by the grenadier kneeling with the GL’s butt on the ground and range estimated by sensing and bracketing the target without using the sight. The safety lever is pushed forward to Fire, the weapon sighted, and the trigger firmly squeezed. The grenadier needs to keep his thumb away from the safety lever to prevent it being cut by the recoil. Recoil is slightly more than the M14’s – 21.5ft/lb – and not uncomfortable. Opening the barrel, the spent cartridge is withdrawn .5in by the extractor and hand-plucked out of the chamber.

After removing the T148 GL’s three-chamber magazine, the rounds were inserted in the chambers and pressed forward until the extractors latched. The cartridges’ rotating bands held the indexing levers down. Set on Safe, a loaded magazine was inserted from the right and pushed in until the left chamber aligned with the barrel. It was set on Fire, aimed, and the trigger squeezed. Fired, the magazine automatically indexed left to the center chamber as the spent cartridge’s rotating band no longer held the lever down and it was now ready to fire. All three rounds having been fired, the magazine was ejected to the left, the extractor releases depressed individually to remove the spent cases, and the magazine reloaded.

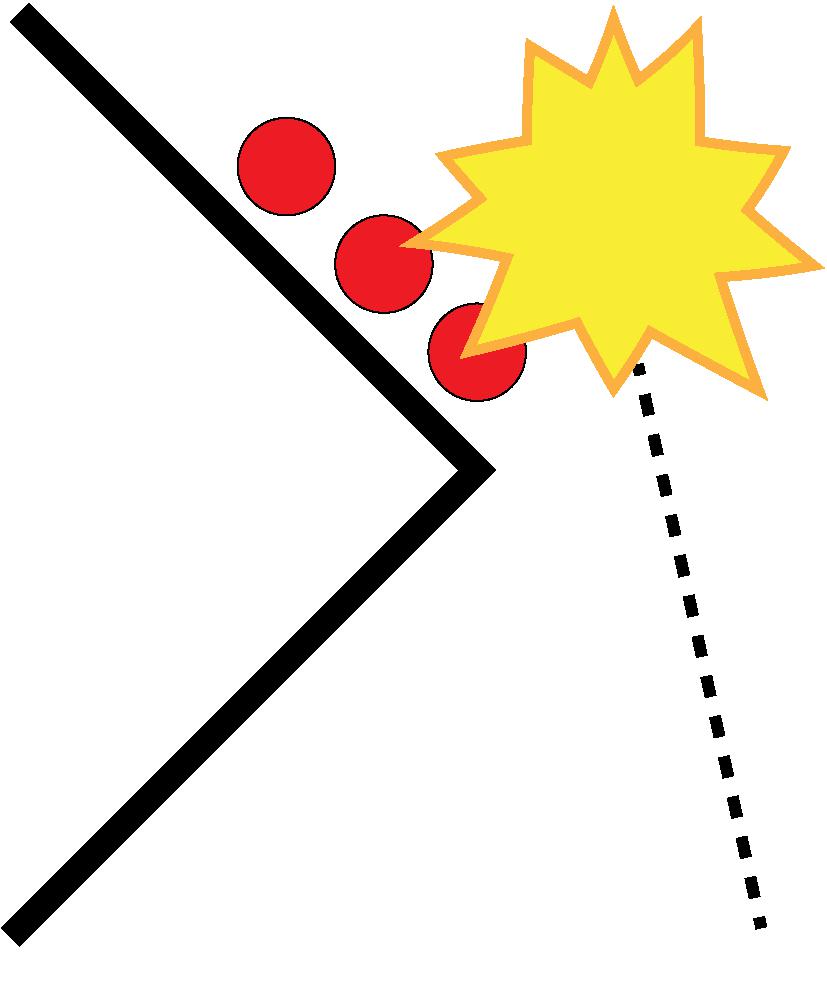

When enemy troops are under cover behind a building corner they may be successfully engaged by firing 40mm rounds to impact at a point on the ground approximately 2–4m (7–13ft) past the building corner. This allows the round to detonate beside or behind the hidden enemy. However, be aware that firing a GL at this low of an angle may not always cause the round to detonate – graze effect low-angle impact. It may ricochet and either detonate farther downrange or not at all. If the first round fails to detonate, the grenadier should be prepared to fire subsequent rounds. It is more effective to simultaneously fire two GLs in this case. Regardless, 2–4 rounds should be fired to ensure sufficient casualties are inflicted.

The XM148 UBGL was more involved to operate than the M79. To load, the barrel-release lever on the back of the pistol grip was depressed and the barrel slid forward – ensuring one’s finger was not pinched between the pistol grip and the forward end of the feed port opening in the bottom of the barrel housing. A cartridge was inserted through the barrel housing feed port into the chamber to engage the cartridge retainer. The safety assembly below the breech was set on Safe (moved left), the trigger extension was pulled to the rear, and the cocking lever pulled. The pistol grip was slid back until the barrel-release latch locked. The trigger was rotated to its firing position and the safety set on Fire (moved right). The weapon was aimed and the trigger gently pulled. After firing the safety was set on Safe, the barrel release depressed, the barrel slid forward to eject the spent cartridge, and the weapon reloaded. There were complaints of the XM148 not handling as well nor as accurately as the M79, a criticism of all UBGLs.

US Marines undertake practice firing with an M203A1 UBGL on an M4A1 carbine fitted with quick-release mounting brackets and the adapter rail system (ARS). The grenadier is aiming with the aid of the GL’s raised leaf sight and the rifle’s front sight. The 40mm barrel is fully forward, providing a 5in opening capable of loading most standard cartridges. (US Marine Corps)

The China Lake GL operated much like a Mossberg Model 500 and similar pump-action shotguns. With the weapon on Safe (lever rearward – Safe, forward – Fire) and the pump handgrip rearward (bolt open), three rounds were loaded into the tubular magazine through the bottom feedway port. A fourth round was hand-chambered through the ejection port and a fifth round could be inserted through the ejection port atop the elevator plate, which was pressed down sufficiently to allow the bolt to clear that round when the pump handgrip was racked forward. The safety was moved to Fire, the weapon aimed in the same way as the M79, and the double-action trigger squeezed. Recoil was light. Racking the pump handgrip back ejected the spent case and the elevator plate positioned the next round to align with the chamber. Racking the handgrip forward chambered the round.

To load the M203 UBGL, the barrel-release latch – located midway along the handguard’s lower left edge – is depressed with the left thumb and the barrel slid forward by shoving the barrel handgrip. A cartridge is inserted through the 5in opening into the breech, the barrel slid rearward until it locks with an audible click, and the weapon is cocked. The safety lever, which cannot be set until the weapon is cocked, is in the forward end of the trigger guard; it is set on Safe by flipping it rearward toward the trigger, which, besides locking the GL, obstructs the finger from gripping the trigger. When firing with a quadrant sight the butt is placed against the shoulder and with the leaf sight the butt is clamped between the underarm and torso. The safety is pushed forward to Fire, the target sighted, and the trigger squeezed. To unload, the barrel latch is pressed, the barrel slid forward, and the expended cartridge will be caught by an extractor on the face of the firing mechanism and fall off. If the grenadier is firing while wearing gloves, the trigger guard can be unclipped at its rear end and pivoted forward. The trigger is single-action, meaning that if a round misfires, the grenadier must wait 30 seconds before opening the barrel, re-cocking, and attempting to fire again.

An M203 UBGL mounted on an M16A1 rifle being loaded with an M781 training practice round – light-blue shatterable plastic projectile and white plastic case. The round generates a puff of orange smoke. Care must be taken with a loosened sling to prevent it interfering with opening, loading, and closing the GL. (US Air Force)

The 5in breech opening allows most cartridges to be fired, but smoke parachute, smoke streamer, and other special-purpose rounds cannot be conventionally loaded. However, the barrel can be removed by pushing the barrel latch and sliding the barrel forward until it hits the barrel stop. On the left side of the handguard, the grenadier must insert a cleaning rod into the fourth hole from the muzzle, depress the barrel stop, slide the barrel forward and off, chamber a lengthy cartridge, and slide the barrel back on until it latches. It has to be removed again to unload – time-consuming, but useful if necessary.

To operate the M320 UBGL, first a systems check is conducted to clear the host weapon and the GL. The grenadier must rotate the selector lever from Safe to Fire and back to Safe, then attempt to pull the trigger, press the barrel release and pivot the barrel outward – ensuring the firing pin is not protruding from the bolt face – set the selector lever on Fire, and press the barrel release while trying to pull the trigger; the hammer should not release.

To load, the grenadier must point the muzzle in a safe direction, set the selector lever on Safe, remove the muzzle cap (it is seldom fitted in combat and would harmlessly blow off if fired), press the barrel release, pivot the barrel, load a cartridge ensuring it is fully seated, and pivot the barrel back into the receiver locking it with an audible click. The GL should be carried in the closed locked position with the selector on Safe.

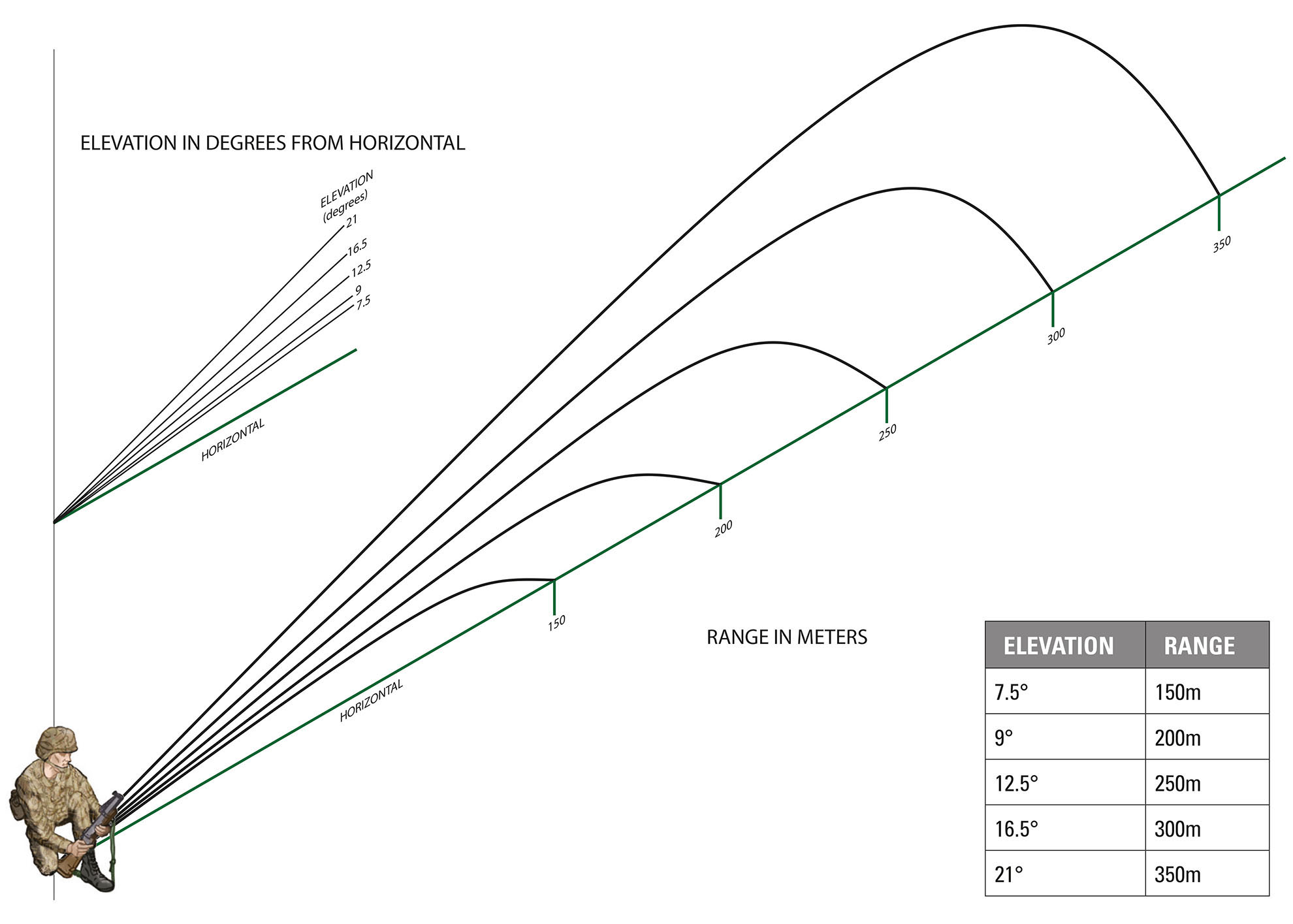

Regardless of the particular model of GL, the elevations given in degrees achieve the stated ranges up to 350m. Since the trajectory is high and the time of flight greater at longer ranges beyond 150m, the wind may have considerable effect upon the accuracy of the projectile and the grenadier must consider this.

To fire the M320, the range is determined by the DNS’s laser rangefinder, a handheld rangefinder, or estimated. The grenadier should ensure the sling hangs to the right side of the weapon or it may interfere with loading the barrel. The grenadier must align and center the front sight’s post with the rear sight’s aperture on the DNS or use the alternate leaf sight, move the selector lever to Fire, and pull the trigger with consistent pressure. The grenadier then sets the selector lever on Safe, presses the release, pivots the barrel, and removes the expended case by hand.

To fire the M32A1/Mk 14 MGL, the safety lever is flipped upward to Safe, the J-shaped release handle in the forward center of the cylinder is unlocked, and the trigger/pistol grip/stock group rotated 90 degrees to the right to expose the cylinder’s six breeches. The cylinder is first charged or wound by turning it 360 degrees counterclockwise to tension the rotating springs by inserting fingers into a chamber or two. The “star extractor” is marked with a semicircular arrow and “WIND.” This can be done before or after chambering the rounds. The rounds are chambered in any order and the stock group rotated into firing position with an audible click when the J-shaped release locks. The weapon is shouldered, selector moved to Fire, sighted with the DNS, and any number of rounds fired semiautomatically as rapidly as the two-stage trigger is pulled. Each pull of the trigger releases tension on the rotating spring to advance the next chamber clockwise to the barrel. The cylinder is opened, tipped downward, and the J-shaped release handle pulled to eject the spent cases and rotated right to charge it.

US Army Special Forces

While the M320 GLM began replacing the M203 within the US Army in 2009, the M203 has remained in use by all US services. This includes the M203 Special Operations Peculiar Modification (SOPMOD) kit used by SOCOM. The SOPMOD M203 is issued in each SOPMOD M4A1 accessory kit, one kit being issued per four M4A1 carbines. While the kit contains various sights and accessories to support four carbines, it contains only one shortened M203 GL with a Knight Armament Corporation quick-attach GL mount, a quick-attach leaf sight, and an AN/PSQ-18A day/night sight (using a common “AA” battery for approximately six hours’ duration). The special M203 SOPMOD barrel is only 9in long as opposed to the 12in barrel of the standard M203-series. Mounted on the M4 the 12in barrel reaches almost to the carbine’s muzzle, while the 9in barrel just reaches the forward mounting bracket. Range is not affected in spite of the loss of one quarter of the barrel’s length. The new M320A1 GLM is shown here being employed in both the under-barrel mode on an M4A1 carbine and in the standalone handheld mode. The latter mode is not as popular as originally envisioned, but some prefer it. The M320 is somewhat more complex than the M203, a complaint expressed by some troops, but is slightly more accurate than the earlier model. Regardless, all 40mm GLs are surprisingly accurate even with simplified sighting systems. Their consistency in hits is due more to the design of the grenade and their quality of manufacture than anything else. This makes them especially effective in hitting small point targets, especially when it is necessary to target windows and firing ports. For this reason 40mm GLs are especially effective in urban combat. Grenades can easily be lobbed accurately through windows up to 125m (137yd), but urban combat ranges are generally shorter. Besides one grenade blowing away any window covering (glass, shutters, louvers, Venetian blinds, screens, wire mesh, heavy curtains), a second should immediately be fired to detonate inside the room, it being more effective to launch at least two grenades into a room to ensure most occupants are neutralized. The small and light pre-scored grenade fragments, while able to kill and wound personnel, often lack the mass and velocity to penetrate through even lightly constructed interior walls.

CARRYING 40mm AMMUNITION

Two New Zealanders of the 1st Australian Task Force carry empty 81mm mortar ammunition crates. The man to the left carries a 7.62mm L1A1 self-loading rifle while the other “Kiwi” carries an M79 GL. The Australians and New Zealanders allotted one M79 per rifle section (squad). (Tom Laemlein/Armor Plate Press)

Initially, there were no special means of carrying the M79. Ammunition was issued in 54lb, 72-round, wire-bound, wooden crates with a foil-backed, white-fabric-covered, cardboard insert containing 12 six-round bandoleers that consisted of two pockets, each holding three rounds. The rounds were further held in white plastic supports – “egg carton cups” – three nose-cups molded in one unit. If the cups were removed, the rounds could easily fall out of the scant pocket flaps. The bandoleer was inadequate for long-term practical carriage, being made of flimsy materials, and did a poor job of protecting the rounds from dust, mud, and rain. Long pyrotechnic cartridges were packed 22 to an M2A1 ammunition can (as used for .50-caliber ammunition) without bandoleers, two cans to a crate.

An ARVN grenadier guarding a freight train in 1971 wears the 1966 M79 grenade-carrier vest with two three-grenade pockets on each side of the front panel, one above the other, and two more on the small of the back. The 24 pockets were each secured by a snapped web strap. The vests were too small for many Americans and were mostly issued to the ARVN. (Tom Laemlein/Armor Plate Press)

The first grenadiers were issued two M1956 universal ammunition cases (two M14 or four M16 20-round magazines), each holding three 40mm rounds – two nose down, one horizontally on top. Occasionally, a round was carried on each side of the cases (“pouches”) secured by the hand-grenade securing loops. Marine M1961 M14 pouches could not hold grenades, so they used bandoleers, canteen covers, and acquired Army M14 pouches.

Firing from a South Korean Army hilltop firebase in 1968, this grenadier could cover a wide sector on the steep hillside with his M79 GL. A six-round bandoleer rests beside him. The bunker’s wide-open firing port allows M26 hand grenades – stowed on a rack on the right – to be thrown through the port. An M17 protective mask carrying case hangs besides the grenades. (Tom Laemlein/Armor Plate Press)

“By the book,” basic load was initially only 18 rounds, but increased to 36. In Vietnam at least that number were carried using expedient means. One M79 grenadier reported carrying 48 HE and ten buckshot rounds. An M203-armed soldier carried 40 rounds.

Seven rounds could be carried in a 1-quart canteen cover, with grenadiers carrying 2–4 covers. An M7 bandoleer (“Claymore bag”) for an M18A1 Claymore mine held ten 40mm rounds in each of its two pockets. M3 bandoleers had seven pockets, each holding 20 rounds of clipped M16A1 ammunition. Sometimes a 40mm round was inserted in each pocket, but they bounced severely when the grenadier was running. Some squad members might carry a 40mm bandoleer that could be passed to grenadiers. ARVN soldiers sometimes had one or two M16A1 bandoleers or 40mm-sized pockets sewn around the bottom hem and/or at waist-level on fatigue shirts. Most grenadiers used a combination of expedient carrying means.

In Vietnam an SF sergeant proposed different vests for riflemen, machine-gunners, and grenadiers, but only that for the grenadier was developed further. The first batch of 1966 trials M79 grenade-carrier vests were too small for Americans and so were issued to the ARVN with limited use by Americans. The vest had two three-grenade pockets on each side of the front panel, one above the other, and two more on the small of the back – 24 rounds. They required the plastic grenade-support cups.

An ARVN grenadier fires at a suspected enemy position during the 1968 Tet Offensive. He carries 40mm rounds in M1956 M14 ammunition pouches and bandoleers. Some 40mm cartridges are carried on the sides of the pouches by hand-grenade securing straps. (Tom Laemlein/Armor Plate Press)

An improved grenade-carrying vest made of nylon fabric arrived in Vietnam in late 1968. On both front panels were six grenade pockets near the bottom, four above those, and two below the shoulders – 24 pockets. In 1972, the top pockets were deepened for pyrotechnic cartridges. That vest remained in service with the 1975 All-Purpose Lightweight Individual Carrying Equipment until the Individual Integrated Fighting System (IIFS) was introduced in 1988 with its ammunition-carrying vest for M203 grenadiers. The IIFS nylon vest had only 14 HE-round pockets and four deeper pyrotechnic cartridge pockets. The overly hot and heavy nylon vest was modified in 1995 with mesh fabric and redesignated the Enhanced Tactical Load Bearing Vest (ETLBV). Unlike the Vietnam grenade vest, other web-gear items were attached to the IIFS/ETLBV.

The much-revised Modular Lightweight Load-carrying Equipment (MOLLE) was introduced in 1997, but did not see widespread use until 2002. The MOLLE allows any combinations of pockets, pouches, and other items to be configured and attached by Velcro®. 40mm pockets, issue and after-market, which many soldiers purchase, are available in one- and two-pocket HE grenade sets and deeper two-pocket pyrotechnic rounds with pockets for 12–18 rounds carried, sometimes “velcroed” over the chest. Additional rounds are carried in utility pouches. In recent years, nylon web belts with up to 8–12 pockets have been used.

This 1st Armored Division soldier in Afghanistan is armed with an M4A1 carbine with an M203A2 UBGL. The M203’s muzzle is almost 1in short of the host weapon’s muzzle. He carries easy-to-reach, immediate-use 40mm rounds in single pockets on a waist belt. The carbine is fitted with a CompM4 M68 close-combat optical sight. (Tom Laemlein/Armor Plate Press)

In 2004 the US Marine Corps adopted the Improved Load Bearing Equipment (ILBE), which retained many of the MOLLE attachable pouches including the 40mm pockets.