And so when we respect our international legal obligations and support an international system based on the rule of law, we do the work of making the world a better place, but also a safer and more secure place for America.

—Condoleezza Rice, former US secretary of state

Rights come first everywhere you look at the United Nations. The purpose of the organization, according to Article 1 of the Charter, is to promote and encourage “respect for human rights and for fundamental freedoms for all without distinction as to race, sex, language, or religion.” The Universal Declaration of Human Rights, as we saw earlier, is literally all about rights (see appendix B). Nearly all states that join the UN have agreed to accept its principles by signing and ratifying two international covenants, one addressing civil and political rights and the other economic, social, and cultural rights. The International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights and the International Covenant on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights, which entered into force in 1976, are legally binding documents. When combined with the Universal Declaration, they constitute the International Bill of Human Rights.

Having rights, real ones that you can actually exercise, requires more than rhetoric and fancy legal language. Rights imply the rule of law, based on the notion that all citizens are equal before the law and that the law will be applied in a rational, consistent manner. You also need mechanisms for protecting and enforcing both the law and the exercise of rights. All of these things are represented in the UN’s law and rights establishment, ranging from national tribunals to an associated international court and a council and an executive dedicated to rights issues. “The UN has meant more to the field of human rights than it has to other fields that it works in,” declares Felice Gaer, a human rights advocate who directs the Jacob Blaustein Institute for the Advancement of Human Rights in New York City. She says that even though the UN has done a lot in areas like security and development, “in human rights it’s been a really big factor.”

Other experts offer a similar assessment. Ruth Wedgwood of Johns Hopkins University praises the human rights treaties as being “a great step forward” for many countries. Esther Brimmer of George Washington University makes a similar point when discussing the emerging nations. “The interesting thing about these countries is that most of them are democracies in some way; their publics have connections to their government. So they’re actually interesting on topics that are relevant to Western countries, issues like human rights or freedom of speech. You want to talk to these emerging countries because they have views on these topics which have credibility. It’s a very different thing than if you’re trying to talk to China.”

The UN is proud of having helped create a large body of human rights law. Most member states have signed and ratified some eighty treaties (also called conventions or covenants) that address particular aspects of human rights. The International Law Commission is the body that does the actual drafting of text for international conventions. Here are only a few treaties, with the year when the General Assembly adopted them for signing:

• 1948 Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide

• 1951 Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees

• 1965 International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination

• 1979 Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women

• 1984 Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman, or Degrading Treatment or Punishment

• 1992 Convention on the Prohibition of the Development, Stockpiling, and Use of Chemical Weapons and on Their Destruction

• 2013 Arms Trade Treaty

When a convention enters force, the UN may create a watchdog committee charged with ensuring that its provisions are honored by member states. For example, when the Convention on the Rights of the Child entered into force in 1989, it was accompanied by the creation of the Committee on the Rights of the Child, which meets regularly and has become an international voice for children. All offices and staff of the UN and its peacekeeping operations are responsible for adhering to international human rights law and reporting possible breaches of it to the proper authorities.

“There has been a deepening of the understanding that human rights and security are related,” notes Esther Brimmer, speaking about an important new way of regarding the role of human rights in the whole UN system. “You can think about the fact that, in history, we tend to put the issue of security in one box and human rights in another box. But actually the argument that you need to have just societies in order to grapple with the issues, so that they don’t degenerate to conflicts, makes sense.” That insight has implications for how the UN system works because it requires that people and agencies working on different aspects of a problem or issue “should be aware and talking to each other about what they see.”

And that is beginning to happen, as Brimmer points out. “So, for example, now the High Commissioner for Human Rights briefs the Security Council. There are times when the human rights commissioner flies in from Geneva and speaks in New York.” Beyond that, “look at the Security Council resolutions; there are more places within the peacekeeping resolutions which include human rights elements. . . . There’s a sense that the observation of the conduct of human rights is part of the security package. Usually you wouldn’t have people even thinking in those terms; that’s a different way of understanding, a holistic understanding of security, that you should try to use these tools together for an overall security.”

The new perspective makes the rule of law and human rights even more important to the UN system than when it was founded, in 1945.

Americans, when they think of the rule of law, may imagine a courtroom scene, dominated by the imposing figure of the robed judge, seated on high, flanked by the jury box, faced by the prosecutor and the defendant, and with a silent, respectful audience sitting in front. Although the UN is not a government, it does have courts and tribunals, some of them as imposing and solemn as any in the United States.

The International Court of Justice (ICJ), also known as the World Court, is one of the six principal organs of the UN. Based in The Hague, the court offers two kinds of services. It gives advisory opinions on legal questions referred to it by UN organs and agencies, and it settles legal disputes submitted to it by UN member states. Sometimes one member state will bring a case against another member state, but in other situations the two contending states may mutually agree to bring their case before the court. In either event, states that bring a case before the court are obliged to obey its decision. The World Court’s first case concerned a boundary jurisdiction involving the United Kingdom and Albania and was filed in May 1947. Between then and July 2013 states brought 153 cases before the court. Among cases in process by then were Peru versus Chile, a maritime dispute; Australia versus Japan, a whaling dispute; and Cambodia versus Thailand, a dispute concerning Cambodia’s Temple of Preah Vihear.

The court’s fifteen judges, who serve nine-year terms, are elected by the Security Council and the General Assembly through a complicated procedure. No two judges may be nationals of the same state.

The International Criminal Court (ICC) is solely a criminal tribunal. Established by the Rome Treaty of 1998, the ICC institutionalizes the concept of an international tribunal for crimes against humanity, war crimes, and genocide. Strictly speaking, it is an independent body, and its prosecutors and eighteen judges are not formally part of the UN. They are accountable only to the countries that have ratified the Rome Treaty (which was sponsored by the UN).

The court is not a venue of first resort. Instead, the accused come before the ICC only if their home country has signed the Rome Treaty but is unable or unwilling to act. To prevent malicious or frivolous accusations, the Rome Treaty requires prosecutors to justify their decisions according to generally recognized principles that exclude politically motivated charges.

Before the creation of the ICC there were no international courts for trying persons accused of committing atrocities. The Security Council tried to fill this gap through the creation of special tribunals designed to bring justice to specific nations ravaged by civil war. It created the first such tribunal in 1993 to investigate massacres in the former Yugoslavia. Other tribunals established by the Security Council or with its cooperation have followed, among them one to address alleged genocide and other crimes in Rwanda (1994); another to investigate atrocities against civilians in Sierra Leone (2002); and another focusing on serious criminal offenses in Lebanon (2007).

The United States has applauded the formation of the UN tribunals and has been their most generous donor, but it has been far less enthusiastic about the ICC. When the Rome Treaty came to the United States for ratification, it got a cool reception. The Clinton administration signed it with reservations based on concerns about the possibility of capricious prosecutions. The George W. Bush administration stated that it would not send the treaty to Congress for ratification without major changes aimed at protecting US military and government personnel against “politically motivated war crimes prosecutions.” It also removed the US signature from the treaty, to the satisfaction of those in Congress who claimed it violated US sovereignty.

Even though the White House and Congress resisted ratification, the rest of the world made the ICC a reality. The Rome Treaty gained enough signatures to establish the court, officially inaugurated at The Hague in 2003. “The ICC does provide an important place to try to begin to deal with some of the accountability issues,” notes Esther Brimmer. “Of course,” she adds, “as a judicial process, it’s relatively slow, and it’s probably a frustration for those who want to move more quickly.”

The ICC tried its first case in 2007, with the filing of charges against an alleged militia leader from the DRC for “enlisting, conscripting and using” children to “participate actively in hostilities.” In 2008, the court’s prosecutor, Luis Moreno-Ocampo of Argentina, began investigating alleged atrocities in the Central African Republic, northern Uganda, and (at the request of the Security Council) the Darfur region of Sudan. The court is also investigating situations that occurred in Côte d’Ivoire, Kenya, Libya, and Mali, and it issued a precedent-setting arrest warrant for Sudan’s president, Hassan al-Bashir, for complicity in war crimes in Darfur. In July 2013 the ICC actually requested that the government of Nigeria arrest Sudan’s president while he was on a visit to Nigeria.

These cases involve Africans, a fact commented upon by some Africans. Brimmer advises the court’s supporters to speak out against “the rather pernicious argument that it only indicts African leaders. I think that’s been a convenient argument from the heads of Kenya and elsewhere, and the African Union. I think it’s up to member states’ parties to try to counter that argument.” It should be noted that as of March 2014 most of the court’s cases had been brought at the request either of the Security Council (Darfur and Libya) or of an African government (Central African Republic, DRC, Mali, Uganda), and only two by the court’s prosecutor.

There are signs that the US government may be softening its stance on the ICC. According to a recent statement by the State Department, the US government supports “the I.C.C.’s prosecution of those cases that advance U.S. interests and values, consistent with the requirements of U.S. law.” It goes on to note that “since November 2009, the United States has participated in an observer capacity in meetings of the I.C.C. Assembly of States Parties (ASP). The United States sent an observer delegation to the I.C.C. Review Conference held in Kampala, Uganda, from May 31 to June 11, 2010.”

Brimmer also sees a better relationship emerging. “The US is trying to show that it supports the norm of the ICC even though in no time soon will it be able to ratify [the Rome Treaty].” She believes “there’s a sense that you would cooperate in terms of providing open-source information when the ICC asks states for relevant information; that you would do that like a normal member state rather than ignoring the request or trying to undermine the request. You respond to the request with your analysis of what’s going on, like a normal state,” rather than giving, as previously, an “actively hostile response.”

Most legal and rights issues do not require a trial in the courtroom. Courts are expensive instruments, and trying cases can consume great amounts of time and money. Both in the United States and the UN, it is usually faster and more efficient to operate through negotiation and discussion to find a mutually acceptable solution that will also be legally and morally sound. In the UN, the Charter places the main burden of examining and resolving human rights issues upon the Commission on Human Rights, created in 1946, and chaired originally by none other than Eleanor Roosevelt.

Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon and Aung San Suu Kyi, Nobel Prize–winning political and rights activist and general secretary of Myanmar’s National League for Democracy, at her residence in Yangon, May 1, 2012. UN Photo / Mark Garten.

For decades the commission was the main UN body for making human rights policy and providing a forum for discussion. It met each year in Geneva, Switzerland, and held public meetings on violations of human rights. When necessary, it appointed experts, called special rapporteurs, to examine rights abuses or conditions in specific countries.

Unfortunately, the commission gained a reputation for biases against certain nations, such as Israel and the United States, and for turning a blind eye to gross rights abuses by authoritarian regimes, such as those in China, Russia, and Iran. Observers commented that the commission’s members often included nations notorious for their failure to observe the human rights standards that the commission was supposed to be monitoring.

The behavior of the commission became such a scandal among US and European member states that something drastic had to be done. The General Assembly agreed to abolish the commission and replace it in 2006 with a new, improved body called the Human Rights Council (HRC). The new body has forty-seven members, elected to three-year terms through secret ballot by the General Assembly. Seats are allotted by world region: thirteen to Africa, thirteen to Asia, eight to Latin America and the Caribbean, seven to Western Europe and other states, and six to Eastern Europe.

Like its predecessor commission, the council makes frequent use of unpaid representatives, called special rapporteurs, or working groups consisting of one or more independent experts, whom it appoints as monitors and in some cases as investigators for human rights issues, either in specific countries (country mandates) or across the spectrum of member states (thematic mandates). The rapporteurs and working groups rely on the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights to provide them with assistance to discharge their mandates.

When the General Assembly appoints members to the council, it is, in the HRC’s own words, supposed to take into account “the candidate States’ contribution to the promotion and protection of human rights, as well as their voluntary pledges and commitments in this regard.” This claim initially drew much attention from critics, who charged that the new council looked and acted a lot like the old commission. Soon after it was inaugurated in June 2006 it began attracting as much criticism as its predecessor, and from the same critics. For starters, its charter members included China, Russia, and Saudi Arabia, whose human rights records were criticized by many Western observers. So unappealing did the new council seem that the US government decided not to seek a seat on it.

That was not what the reformers had planned. “Our original idea, which the Europeans shared,” says former US ambassador John Bolton, “was that we would have a whole series of procedural changes to the new Human Rights Council that in the aggregate would result in a divergent kind of membership from the Human Rights Commission, so that you wouldn’t have those abusers of human rights or simply countries that didn’t much care about human rights and were on the commission just because it was a good thing to be on.” Bolton accuses the Europeans of failing to push for reforms that the United States wanted, which meant “that the new body was not going to be that much divergent from the prior body, and in fact that’s exactly what happened. That’s one reason we voted against it in 2006, because we said it’s not much divergent from the Human Rights Commission.”

Rights expert Ruth Wedgwood agrees that the Europeans did not push hard enough for meaningful changes in the new council. “The attempted reform was done too quickly,” she argues. “The number of countries was only slightly cut down and the predominance of the South was increased. With regional loyalties, even on human rights issues, this made it more likely that the council would spend the bulk of its disposable time on Israel and Palestine.” UN insider Jeffrey Laurenti is similarly critical of “this crazy drive to shrink it,” which meant the loss of four Western seats. “What were these people thinking?” he asks.

From the other side of the aisle, however, the council didn’t look so flawed. According to Pakistan’s former ambassador Munir Akram, the old Human Rights Commission was accused of being “a one-sided body, a politicized body, and ineffective in defending human rights,” so it was proposed to create a smaller council “to keep the riffraff out so that the major powers could have a smaller body in which they could take the ‘right’ decisions.” According to Akram, the developing countries argued that whatever the size of the proposed council, “it should reflect the actual composition of the General Assembly and the regional groups in the General Assembly.” Since, by Akram’s math, more than 130 of the 193 UN member nations fall into the developing category, they should arguably constitute the great majority of members of the Human Rights Council.

That is actually how the council was set up, remarks Akram, and “some of our friends in the North are not happy about that.” It was mere coincidence, he says, that when the council began its work, unrest and war broke out in Lebanon and Gaza, so the council addressed those events. The Europeans had insisted that a special session of the council could be called by only one-third of the members. “Well, guess what: two can play the game,” says Akram, “and therefore special sessions were called by our Arab friends on Palestine and Lebanon, and now it’s been said that the council is targeting Israel. But conditions and procedures were dictated by the very same countries that are complaining about it right now.”

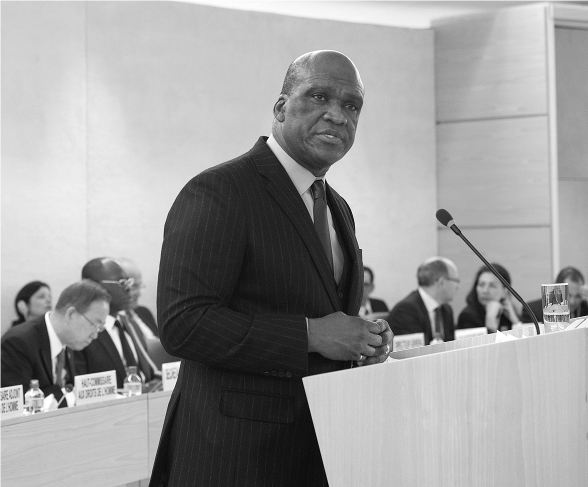

John Ashe, president of the sixty-eighth session of the General Assembly, addresses the opening of the twenty-fifth regular session of the Human Rights Council, Geneva, March 3, 2014. UN Photo / Eskinder Debebe.

Ruth Wedgwood saw the council’s initial actions as evidence that the old politics were returning. She was especially concerned that North-South issues might tarnish one of the procedural safeguards that the Europeans managed to retain in the new council, the Universal Periodic Review (UPR). That is a regular process of issuing reports on the compliance of each UN member nation with human rights norms, including its obligations under the specific human rights treaties that it has joined. Such reports have value only if conducted in an impartial and rigorous manner, “and they could be positively dangerous if countries lie about their handling of rights.”

The Obama administration decided in 2009 that instead of sniping from the sidelines, it was better to join the council and exercise leadership in the proceedings. The State Department’s view in a 2013 report was that American leadership had produced significant results in a variety of places, ranging from human rights in Belarus, Syria, and Eritrea to women’s rights around the world. “As a member of the Council,” notes the report, “the United States’ mission remains to highlight key human rights issues while vigorously opposing efforts to shield human rights violators.”

UN insiders generally agree that the Obama administration’s decision to engage the council had a beneficial impact. Brimmer praises Washington’s participation. “The most important thing the United States has done at the UN in the last five years has been to normalize relations in the Human Rights Council, hands down,” she says without hesitation. It has been able to move proceedings away from sterile debates about Israel to discussions on current issues like Libya, Syria, and North Korea. Stewart Patrick of the Council on Foreign Relations largely agrees. “One of the things which would have to be counted as a success is the Obama administration’s efforts to engage the Human Rights Council and turn it into a useful instrument,” he declares. “That statement remains controversial. There are those who continue to believe that the Human Rights Council is a den of abusers—and it does include abusers, of course—but not in the sense that it puts the foxes in charge of the hen house.” Rather, he asserts, “if you look at the success that the administration has had in rolling up its sleeves, they got a bunch of resolutions condemning the actions of particular governments including Syria, while the Security Council wasn’t doing very much. At least it’s managed to keep a number of abusers . . . off of the Human Rights Council, and through the system of Universal Periodic Review it’s managed to shed light on some of the abusers. It’s made things better so that the glass is half full as opposed to before,” when it was “most certainly half empty, more than half empty.”

However, the improvements came after an initial period of chaos, argues Hillel Neuer of UN Watch, and have only returned things to the generally “depressing” level of the old Human Rights Commission. He notes that while recent Human Rights Council resolutions had indeed targeted rights abusers like Iran, other nations, like Saudi Arabia and China, have totally escaped discussion. The United States and other Western nations are unwilling to challenge those member states, he says. They have received “a free pass.”

Criticisms of the council sometimes obscure the presence of another force in the UN rights establishment. In 1993 the General Assembly established the post of UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, responsible to the secretary-general. The high commissioner’s office is charged with being a secretariat for the Human Rights Council, overseeing the UN’s human rights activities, helping develop rights standards, and promoting international cooperation to expand and protect rights. The office does not control the Human Rights Council, nor does it have much influence over it or its special rapporteurs.

“The high commissioner’s role is not defined, so it’s up to each high commissioner” to define it, says Wedgwood. “Part of the work of the overall job is to help coordinate the development of the jurisprudence of the human rights treaty bodies. This has been a challenge because each of the committees is made up of volunteers and has its own trajectory. You also have the problem of countries having to report on multiple topics to multiple treaty bodies and of the committees potentially taking divergent views of issues.”

The first high commissioner was José Ayala-Lasso of Ecuador, who was succeeded in 1997 by Mary Robinson, former president of Ireland. Her successor was Sérgio Vieira de Mello of Brazil, who in 2004 was succeeded by Louise Arbour of Canada. In 2008, Ban Ki-moon named Navenethem (Navi) Pillay, a South African judge and the former president of the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda, as the next commissioner. She was succeeded in fall 2014 by Prince Zeid Ra’ad Zeid al-Hussein of Jordan.

A Security Council debate on the promotion and strengthening of the rule of law in the maintenance of international peace and security, February 19, 2014. Linas Antanas Linkevičius, foreign minister of the Republic of Lithuania and president of the Security Council for February, chairs the session. On his right is Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon. UN Photo / Evan Schneider.

Everyone is “for” human rights, but people may not agree on how to enforce rights when they seem to conflict with national sovereignty. If mass atrocities are being committed within a nation—something that has happened with lamentable frequency—does the world community have the obligation or the right to intervene to stop it? The usual response over the decades has been no.

Kofi Annan proposed to alter the historical approach by arguing that international human rights law must apply in each member state and that certain acts, such as genocide, war crimes, and crimes against humanity, cannot be allowed to occur with impunity. He based his view, no doubt, on his own bitter recollection of events in places like Rwanda and Bosnia, where the UN was accused of doing too little to prevent mass murders. Annan was under-secretary-general for peacekeeping during those years (1992–96).

Annan formally stated his new approach to intervention in an address at the General Assembly in September 1999, in which he asked member states “to unite in the pursuit of more effective policies to stop organized mass murder and egregious violations of human rights.” Conceding that there were many ways to intervene, he asserted that not only diplomacy but even armed action was an acceptable option. Many leaders in Africa were coming to the same conclusion. Representatives of nations drafting the Charter of the African Union (AU) in 2000 declared in Article 4(h) that it is the “right of the Union to intervene in a Member State pursuant to a decision of the Assembly in respect of grave circumstances, namely war crimes, genocide and crimes against humanity.”

At Annan’s urging the Canadian government established the International Commission on State Sovereignty, whose report, issued in 2001, laid out the basic principles of what became known as the responsibility to protect (R2P). In 2005 world leaders at the UN World Summit endorsed the concept, and in 2009 Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon issued a report, Implementing the Responsibility to Protect, that sought to make the concept into a working principle. This basic document set forth the three pillars of R2P:

1. States have the primary responsibility for protecting their citizens from genocide, war crimes, crimes against humanity, and ethnic cleansing.

2. The international community is responsible for helping states protect their citizens from these crimes.

3. The international community is responsible for acting decisively and in a timely manner to prevent or halt these crimes when a state is evidently failing to protect its citizens.

Since the secretary-general’s report, R2P has been invoked by various parties, including the UN and human rights NGOs. The Security Council has embraced it and incorporated it into numerous resolutions. The council first mentioned the term officially in 2006, in Resolution 1674, on the protection of civilians in armed conflict, and later referred to the resolution when passing Resolution 1706, authorizing deployment of a peacekeeping mission to Darfur. Later council resolutions and statements mentioned R2P as an issue—for example, in Libya (Resolutions 1970 and 1973), Côte d’Ivoire (Resolution 1975), South Sudan (Resolution 1996), Yemen (Resolution 2014), and the Central African Republic (Resolution 2121).

Edward Luck, an expert on R2P, praises Annan for “putting humanitarian intervention on the map” and expressing “the dilemma facing the international community.” He also recognizes that R2P is a controversial issue. Pakistan’s former permanent representative Akram, like some other observers, sees R2P as merely a “slogan,” and not even a necessary one. “International humanitarian law already allows the international community to act in cases where there are such crimes—war crimes, genocide, crimes against humanity,” he maintains. “You don’t need new decisions or new conventions for that purpose.” He elaborates. “Wherever there has been genocide—in Srebrenica or Rwanda—in recent years, it has been because of the failure of the great powers to allow the international community to act. Srebrenica, we know what happened: the Security Council would not send troops to protect those defenseless people, who we knew were going to be slaughtered, and the Dutch troops stood by while the slaughter happened. So where is the R2P?” Akram maintains that responsibility for failing to protect lies not with the developing countries but with the major powers, “and therefore this is an exercise to salve their conscience.”

The controversy over R2P has also brought complaints that it could be used as a pretext for other aims. That charge has been made in connection with the Security Council’s decision to intervene in the Libyan civil war that toppled dictator Muammar Gaddafi. Civil unrest became overt in 2011 and soon moved to open conflict between rebels and the government. Speeches by Gaddafi and the actions of his military forces suggested that the government would try to suppress the uprising brutally.

Attempts by the United Kingdom, the United States, and other nations and regional groups, including the African Union, to encourage a political resolution did not bring peace. The Security Council decided to intervene, first with Resolution 1970, passed unanimously in February 2011, which declared that the Libyan government had a responsibility to protect its citizens. It also imposed an arms embargo and other sanctions and asked the International Criminal Court to investigate allegations of crimes against humanity. When the Libyan government seemingly ignored the resolution, the Security Council passed a much stronger one, Resolution 1973, in March that, among other items, authorized UN member states to impose a no-fly zone over Libya and apply all measures necessary to protect civilians in threatened areas.

Proponents of Resolution 1973 argued that peaceful attempts to prevent crimes against humanity had failed and that there was no alternative to the use of military force. A significant minority of council members—China, Brazil, Germany, India, and Russia—had reservations about the resolution, though instead of opposing it, they simply abstained from voting. Some skeptics wondered whether all peaceful means really had been exhausted. The African Union thought more could be done. Moreover, the application of military force raised serious issues: How much force, and for how long? Should it be aimed solely at protecting civilians, or could it be applied to advance the cause of the rebels?

NATO air forces immediately began airstrikes to stop the Gaddafi regime from sending tanks against civilians. They also helped the rebels counterattack the government forces and eventually take control of the country. According to Mark Malloch-Brown, the airstrikes went beyond the scope of the Security Council resolution. “Somehow this correlation was being introduced between R2P and the right to intervene,” he remarks. “In fact the R2P doctrine was always meant to assume a lot of pre-intervention effort to mitigate, head-off, or resolve conflict, and was not meant to be a rush to arms.” As he sees it, “R2P rests on a concept of individual rights vs. state rights that is very European and not universally accepted.” To make it work requires “a clear framework of agreed action” that will not be exceeded. “It’s got to become a code of interstate conduct which is fully respected even when it means that some jerk doesn’t lose his presidential palace. The purpose is to prevent him from hurting his citizens, not to open up a generalized effort to remove him, even though logic may often—and Gaddafi was an example—impel the idea that the only way to remove the threat is to remove him.”

Part of the fallout from the Libyan intervention, in Malloch-Brown’s view, has been a loss of trust among the five permanent members of the Security Council. The Chinese and Russians may, he says, now see R2P as simply a device to justify intervention that may involve regime change and other goals not directly related to protecting civilians. That concern, he argues, was a major reason why China and Russia prevented attempts by the Security Council to intervene strongly in the Syrian civil war. The United States and its allies, however, may take a different view of R2P.

Caught in the middle is the secretary-general, who must satisfy all P5 members if he is to attain his objectives. Ban Ki-moon shows no sign of wavering. Rather, he has been a staunch supporter of R2P since the day he took office in 2007. Madeleine Albright thinks Ban is doing the right thing. “The secretary-general keeps pushing,” she says, “and ultimately we have to show that the concept of national sovereignty and the responsibility to protect can work together.”