THE FOLLOWING NOTES ARE MEANT ONLY AS A USEFUL guide to the uncommon ingredients that are called for in these recipes, basic cooking utensils, and measurements. More detailed information on other ingredients, including chiles, cooking methods, etc., can be found in From My Mexican Kitchen: Techniques and Ingredients.

COOKING EQUIPMENT

In Mexico one cannot visualize a kitchen without a comal, molcajete (the traditional mortar and pestle made of volcanic rock), or cazuelas and a tamale steamer.

• A comal is a disk of thin metal or unglazed clay that goes over a stovetop burner or fire for cooking tortillas or char-roasting ingredients, mainly for table sauces. Use a heavy cast-iron griddle if you have no comal.

• Cazuelas are wide-topped glazed clay pots for cooking on a gas flame or over wood or charcoal. They are not suitable for an electric burner. Heavy casseroles, such as Le Creuset, or heavy skillets of different sizes can be substituted.

• A blender, preferably with two jars, is endlessly useful.

• A food processor is useful for only a few recipes, where stated. It will never blend a chile or other sauce as efficiently as a blender.

• Tamale steamer or how to improvise one: The ideal, of course, is to find a simple metal Mexican tamale steamer with four parts: a straight-sided, deep metal container with a perforated rack that sits just above the water level, an upright divider to support the tamales in three sections, and a tight lid (illustrated in The Art of Mexican Cooking). This type of steamer can often be found in a Mexican or Latin American grocery along with the molcajetes and tortilla presses. Failing that, any steamer can be used as long as the part holding the tamales is set deep down near the concentration of steam—tamales must cook as fast as possible so that the beaten masa firms up and the filling doesn’t leak into it, a messy affair! A couscous steamer is not suitable for that reason.

I have had to improvise on many occasions: I think the most successful was a perforated spaghetti or vegetable holder, which normally sits down into the water, set onto four upturned custard cups so as to hold it just above the level of the water—which should be about 3 inches deep. To hold in as much steam and heat as possible, cover the top of the pot with tightly stretched plastic wrap. (But remember to prick and deflate it before inspecting the tamales.)

MEASURES AND EQUIVALENTS

I have attempted to give both weights and cup measures where feasible.

For liquid measures I use a standard 8-ounce (250-milliliter) glass cup, and for solids an 8-ounce (250-milliliter) metal cup. Preferably measuring cups should be the standard ones with straight sides and not those plastic ones in fancy shapes.

When I refer to 8 ounces (225 grams), I mean weight, not the 8-ounce liquid measure. For example, 1 cup (250 milliliters) of corn masa weighs about 9 to 9-1/2 ounces (250 to 262 grams) and may even weigh a little more if it is very damp. A cup (250 milliliters) of dry tamale masa weighs about 6 ounces (180 grams).

I always try to persuade cooks to buy a good heavy-duty scale, not the light ones that hang from a wall and bounce around or those that have a container that slips off its base with the slightest movement. Not only will you weigh more accurately but you’re spared the messy business of forcing fat into cups and then having to scrape it out and deal with a greasy sink.

INGREDIENTS

See the General Index for ingredients that are featured in boxes throughout the book: pulque, chilacayote, pozole, chicharrón, zapote negro, chaya, dried shrimp, avocado leaves, and asiento.

Fats and Oils

Pork lard is still used in many areas for cooking: it’s either a pale cream color or a much darker stronger lard that comes from the bottom of the chicharrón vat. The latter is often used with the little bits of chicharrón still in it and called asiento.

The taste lard gives to these traditional dishes is simply incomparable, and it actually has less saturated fat and cholesterol than butter. If you don’t have access to good fresh lard (from a Mexican or German butcher, not the over-processed blocks at the supermarket, which are often beef fat), it’s very easy to make your own.

Preheat the oven to 325°F (165°C).

Chop a pound or two of pork fat into small cubes, discarding any bits of tough skin. A handful at a time, mince that fat in a food processor.

Place it in one or two heavy skillets on top of the stove and heat over medium heat until the fat has rendered out. Strain out the crunchy little bits and give them to the birds.

Store the lard, tightly sealed, in the refrigerator, where it will keep for several months.

Vegetable oil of several types is available in Mexico, but I still prefer safflower oil, called cártamo or alazor. Corn oil tends to be too heavy.

Olive oil is occasionally used for recipes that are more Spanish in origin.

Vinegar

If not otherwise stated in the recipe, any commercial vinegar will do. To make a mild vinegar it is best to mix half rice vinegar with a good-quality wine vinegar.

Many Mexican cooks, especially those living in the provinces, make and use a mild pineapple vinegar (see recipes in The Cuisines of Mexico, now included in The Essential Cuisines of Mexico and The Art of Mexican Cooking). In Colima the vinegar is pale and honey colored, made of fermented tuba, the sap from a local palm tree. In Tabasco and Veracruz a delicious vinegar is made from overripe bananas.

BANANA VINEGAR

[MAKES 1 PINT]

4 pounds overripe bananas

You will need 2 containers: one with a perforated bottom that sits firmly into a second nonreactive container. Slit the skins of the bananas, but do not remove them, and press them into the top container. Cover with cheesecloth and a lid and set in a warm, damp place. A pale orange-colored liquid will exude and collect in the bottom container. Little flies will invade, and there will be a rich brewing smell. Foamy cream-colored flecks will appear in the liquid—don’t worry. From time to time, press down on the rotting bananas. Given the right amount of heat and humidity, this first process can take about 2 weeks and up to 1 month. When you see that the bananas will yield no more juice you are ready to proceed.

Have ready a sterilized glass container and strain the liquid into it through cheesecloth. Cover the jar and set in a warm place. As the days go by, a thick skin will form on the surface. Don’t worry, this will gradually turn into the “mother,” a gelatinous substance that makes for good vinegar. After 2 weeks the vinegar should have attained full strength and a pleasant acidity. Remove the top layer and rinse so that you have an almost transparent gelatinous mother. Put this back into the jar. I have kept this type of vinegar for several years.

Cheese

The most difficult cheese to find a substitute for is queso fresco. In Mexico it is traditionally sold in small round cakes about 2 inches (5 centimeters) thick. When made correctly, it is an unsophisticated but delicious cheese that is crumbled on top of antojitos (masa snacks), enchiladas, etc., or used for stuffing chiles and quesadillas.

To make queso fresco, whole milk is clabbered, the curds are drained, and then they are ground to fine crumbs. They are then pressed into wooden hoops and left to drain off the excess whey. The cheese should be creamy colored, pleasantly acidy, and melt readily when heated. Very few commercial copies of queso fresco in the United States fulfill those requirements, with one notable exception that I know of (I hope now I shall hear of others), made by the Mozzarella Cheese Company in Dallas (2944 Elm Street, Dallas, TX 75226; 214-741-4072). Once you find a good one, always buy extra and freeze it for up to three months.

For many antojitos the dry, salty cotija or añejo cheese may be used, but it will not—and should not—melt easily. Several good ones are distributed in the United States, but alas, they are cut into pieces from a large wheel and often no brand name is put on the package.

For stuffing chiles, etc., use my standby, Muenster (domestic, not imported), which melts easily.

Epazote

Epazote, Teloxys (formerly Chenopodium) ambrosioides, is a North American herb that grows wild in poor soil. It has pointed, serrated leaves and a clean, pungent taste—a little like creosote. It is an essential flavor in the cooking of central and southern Mexico. Tortilla soup is not a real tortilla soup without it! You may find it in a Mexican grocery or at the farmers’ market, but it’s easy to grow (see “Sources for Ingredients” in this chapter).

Achiote

Achiote paste—annatto seeds ground with other spices and mixed with crushed garlic and vinegar or bitter orange juice—is a popular seasoning in recipes from the Yucatecan peninsula. However, in Tabasco and the Isthmus of Tehuantepec they use pure achiote, which is just the coloring boiled from the seeds and reduced to a paste. The pure paste is hard to come by elsewhere, but the Yucatecan paste is distributed widely in Mexico and the United States under different brand names, the most popular of which is La Anita.

To make the paste at home, see The Art of Mexican Cooking.

Hoja Santa

This large, heart-shaped leaf of a tropical shrub, Piper auritum, with a pronounced anisey flavor is used to season foods in the southern part of Mexico. It also grows wild along Texas riverbanks, I am told; it is often referred to as the rootbeer plant and the flavor likened to sarsaparilla.

In some recipes the flavor may be replaced by avocado leaves, but for others there is no substitute.

I have seen plants for sale in many nurseries throughout the Southwest, and occasionally Mexican markets will sell packages of the dried leaves, but they tend to crumble to dust.

Broiling Tomatoes

This technique gives tomatoes a very special depth of flavor; it’s used for a lot of cooked and fresh sauces, and it’s a great way to preserve a large harvest for the winter months—just broil the tomatoes and store them in the freezer.

For just one or two tomatoes, roast them on an ungreased comal over medium heat, turning from time to time, until they’re blistered and brown all over. For a bumper crop, choose a baking sheet just large enough to hold the tomatoes and place them on it. Broil them 2 inches from the heat, turning frequently until they’re blistered and brown and soft inside. Scoop them up, including the juices, and use them in recipes or store in 1-pound batches in the freezer.

SALSA COCIDA DE JITOMATE

COOKED TOMATO SAUCE

[MAKES ABOUT 2-1/4 CUPS (563 MILLILITERS)]

A good basic tomato sauce with its origins in the Sierra Norte de Puebla. You need delicious ripe tomatoes for this sauce; canned or out-of-season tomatoes just won’t deliver the flavor.

1-1/2 pounds tomatoes (675 grams)

4 chiles serranos

2 garlic cloves, peeled and roughly chopped

3 tablespoons safflower oil

Sea salt to taste

Put the tomatoes in a saucepan with the chiles, cover with water, and bring to a simmer. Continue to cook at a fast simmer until the tomatoes are fairly soft but not falling apart—about 5 minutes. Set aside.

Put the garlic and 1/3 cup (83 milliliters) of the cooking water into a blender jar and blend until you have a textured consistency—about 5 seconds. Add the tomatoes and blend for a few seconds; the sauce should have a roughish texture.

Heat the oil in a frying pan or cazuela, add the sauce, and cook over high heat, stirring from time to time and scraping the bottom of the dish, until reduced and the raw taste of garlic has disappeared—about 6 to 8 minutes. Add salt to taste.

CALDILLO DE JITOMATE

A SIMPLE TOMATO BROTH

[MAKES ENOUGH BROTH FOR 4 LARGE CHILES]

Chiles rellenos are usually reheated in a simple tomato broth such as this one. You could also add a bay leaf, 1/4 teaspoon dried thyme, a 1/4-inch (7-millimeter) piece of cinnamon stick, and a clove.

3/4 pounds tomatoes, roughly chopped, unpeeled (340 grams)

2 tablespoons finely chopped white onion

1 garlic clove, peeled and roughly chopped

1/2 cup (125 milliliters) water

1-1/2 tablespoons safflower oil

2-1/2 cups (625 milliliters) chicken broth or pork broth

Sea salt to taste

Put the tomatoes, onion, and garlic with the water in a blender jar; blend until fairly smooth.

Heat the oil in a heavy pan, add the blended ingredients, and cook over fairly high heat until reduced and thickened—about 10 minutes. Add the broth, adjust seasoning, and cook for 5 minutes more.

Add the stuffed and fried chiles and cook gently, turning them over very carefully, for about 10 minutes.

BITTER ORANGE SUBSTITUTE

[MAKES ABOUT 1/2 CUP (125 MILLILITERS)]

2 tablespoons fresh grapefruit juice

2 tablespoons fresh orange juice

1 teaspoon finely grated grapefruit rind

1/4 cup (63 milliliters) fresh lime juice

Mix everything together thoroughly about 1 hour before using. Keep in the refrigerator, tightly sealed, no more than 3 or 4 days.

POACHED AND SHREDDED CHICKEN

[MAKES ABOUT 2 CUPS (500 MILLILITERS)]

1 large chicken breast, about 1-1/2 pounds (675 grams), with skin and bone

3 cups (750 milliliters) chicken broth

Salt as necessary

Cut the chicken breast in half and put into a pan with the chicken broth. Bring to a simmer and continue simmering until the meat is tender—about 20 minutes. Set aside to cool off in the broth. Remove skin and bone and shred the meat coarsely. (If it is shredded too finely, the meat loses flavor.) Add salt. Reserve the chicken broth for another dish.

MASA PARA TORTILLAS

MASA FOR CORN TORTILLAS

[MAKES 1-3/4 POUNDS (800 GRAMS)—3-1/4 CUPS (813 MILLILITERS)]

I have always slavishly followed the method of preparing dried corn for tortilla masa that most of my neighbors and my early teachers employed. But one day Señora Catalina, who comes to care for the masses of flower pots I have dotted around the terraces, told me of another method. “It will give you the most delicious masa,” she said. Here is her method:

1 quart (1 liter) water

2 scant teaspoons powdered (slaked) lime

1 pound (450 grams) dried corn, about 2-3/4 cups (688 milliliters)

Heat the water in a large nonreactive pan. Stir in the lime and bring to a rolling boil. Add the corn, stir well, cover, and again bring to a rolling boil. Set aside, still covered, until the following day, a minimum of 12 hours. Then rinse the corn well, strain, and grind it, or send to the mill to be ground to the required consistency: either very smooth for tortillas or martajada or more rough-textured for some types of antojitos or tamales.

LIME (CAL)

In Mexico slaked lime (calcium oxide) is generally used (with minor exceptions) to prepare dried corn for masa for tortillas and tamales. The lime comes in small rocks, which you can see for sale in Mexican marketplaces. In the United States, your best source is a garden supply store, and you may have to buy a lifetime supply, since it usually comes in very large bags.

Once you have the lime, it needs to be slaked. Take a piece about the size of a golf ball and crush it as completely as you can. Put it in a noncorrosible bowl (and be careful not to get any near your eyes). Sprinkle the lime well with cold water; it will hiss impressively and send up a little vapor. Once the action subsides, your lime is slaked to a powder. Dilute with water, and then pour the milky liquid through a strainer into the corn water for the masa.

Take a taste before you cook the corn: there should be a slightly acrid burn; if it seems really strong and bitter, dilute it a little; if it’s weak, add a little more lime.

Store any remaining lime in a tightly sealed jar. Over time it will slake on its own, as it draws moisture from the air—you can still use it, though it won’t fizz up in the same way.

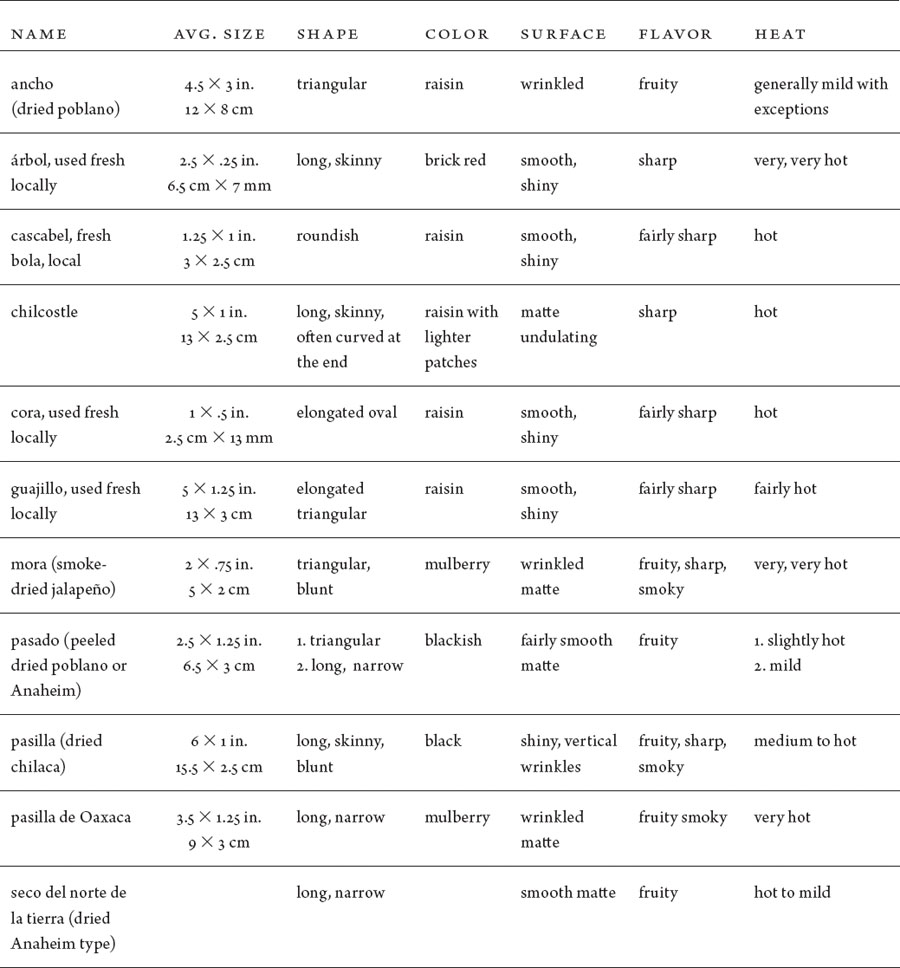

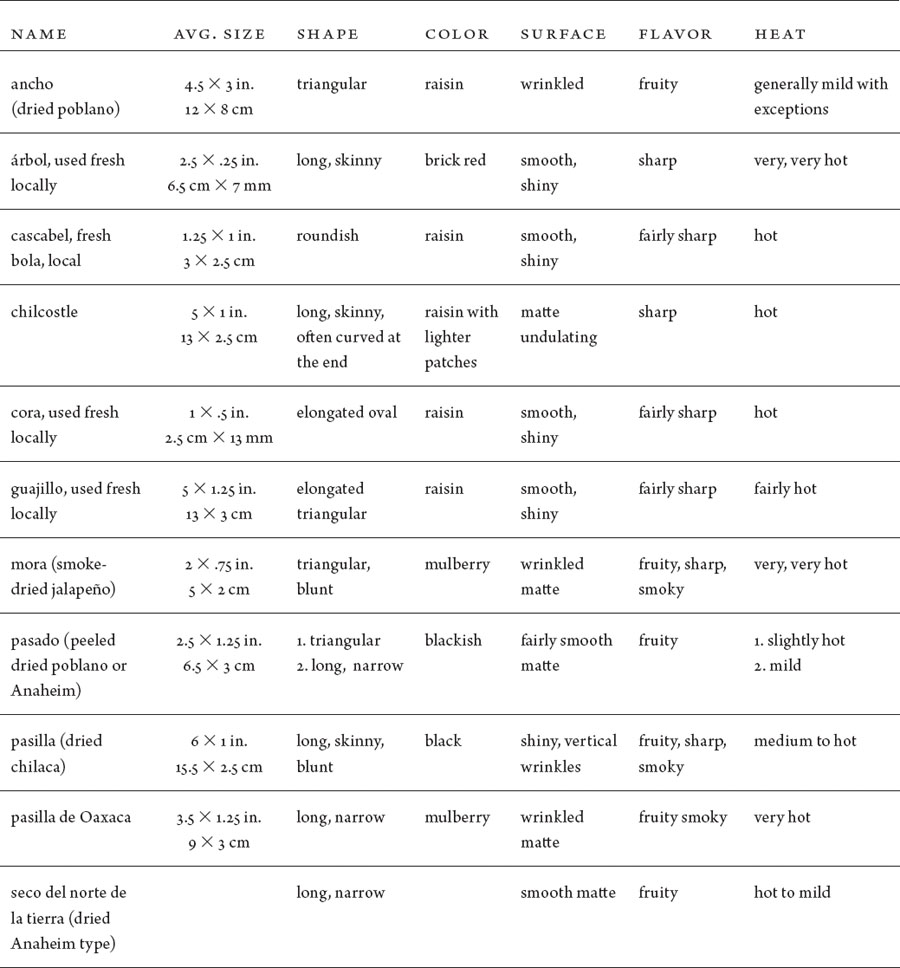

DRIED CHILES REFERRED TO IN THIS BOOK

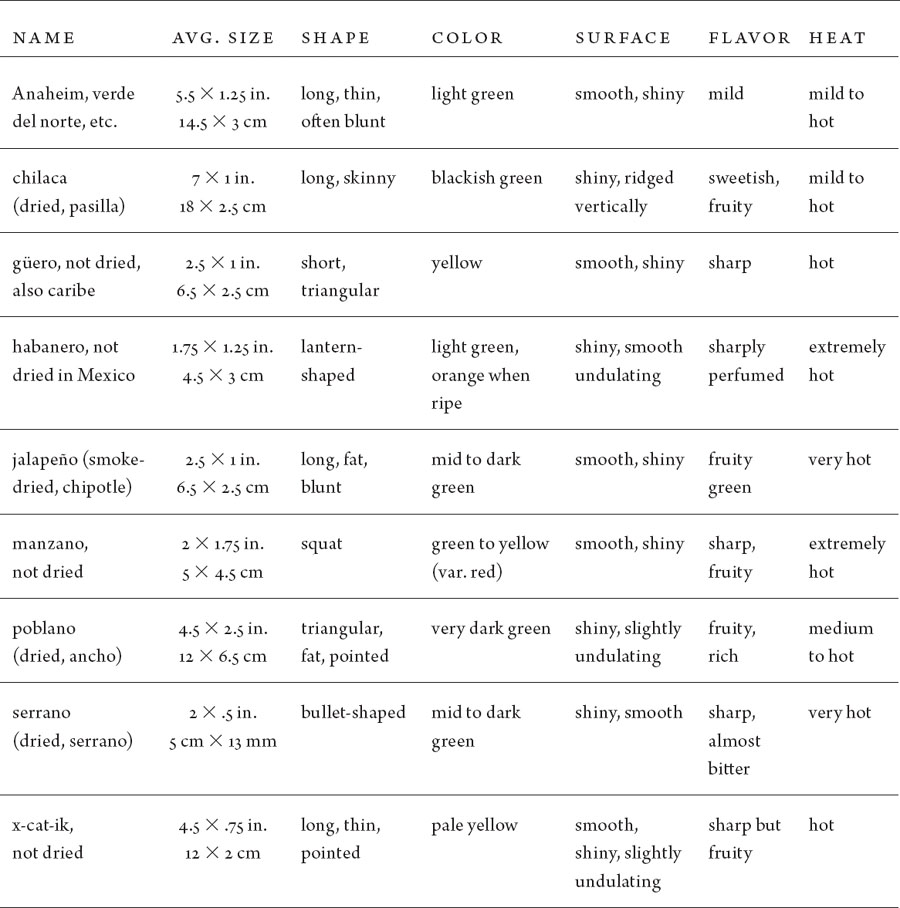

FRESH CHILES REFERRED TO IN THIS BOOK

While a limited number of ingredients for Mexican recipes are found locally in most supermarkets, the variety depends very much on which part of Mexico the Mexicans in that area are from.

The Internet provides a valuable source for certain ingredients: e.g., The Chile Guy in New Mexico, www.thechileguy.com. Some Oaxacan chiles (chilhuacles and costenos), many types of Mexican beans, Mexican oregano, dried sour tunas (dried xoxonostles), and dried chipotles can be ordered through the website of Rancho Gordo, www.ranchogordo.com.