Chapter 2

The Written Word: Checking out Chinese Characters

In This Chapter

Familiarizing yourself with the Six Scripts

Familiarizing yourself with the Six Scripts

Using Chinese radicals as clues to the meaning of a character

Using Chinese radicals as clues to the meaning of a character

Getting a handle on character type, writing, and order

Getting a handle on character type, writing, and order

Knowing how to use a Chinese dictionary

Knowing how to use a Chinese dictionary

Make no bones about it. (Oracle bones, that is.) China has literally hundreds of spoken dialects but only one written language. That’s right: When a headline hits the news, people in Shanghai, Chongqing, and Henan are all yakking about it to their neighbors in their own regional dialects, but they’re pointing to the exact same characters in the newspaper headlines. The written word is what’s kept the Chinese people unified for over 4,000 years.

This chapter gives you the low down on how Chinese wénzì 文字 (wuhn-dzuh) (writing) actually began, how characters are constructed, and which direction they’re going in when you read them. I describe how you may be able to identify the basic meaning of a character by looking at a key portion of it (called the radical) and how characters used by people living in Taiwan are different from characters used by people in mainland China. And because Chinese has no zìmǔ 字母 (dzuh-moo) (alphabet), I show you all sorts of ways you can look words up in a Chinese dictionary.

Perusing Pictographs, Ideographs, and the Six Scripts

You already know that Chinese words are written in beautiful, sometimes symbolic configurations called characters. But did you know that you can classify the characters in a variety of ways?

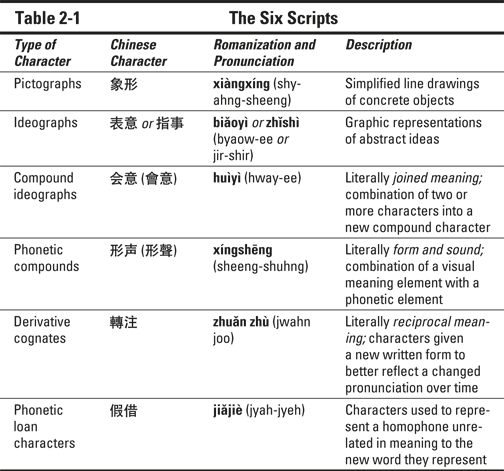

During the Hàn 汉 (漢) dynasty, a lexicographer named Xǔ Shèn 许慎 (許慎) (shyew shuhn) identified six ways in which Chinese characters reflect meanings and sounds. These designations are known as the liù shū 六书 (六書) (lyoe shoo) (the Six Scripts). Of the six, four were the most common:

Xiàngxíng 象形 (shyahng-sheeng) (pictographs): These characters resemble the shape of the objects they represent, such as shān 山 (shahn) (mountain) or guī 龜 (gway) (the traditional character for turtle; the simplified character for turtle — 龟 — doesn’t really look as much like a turtle). Pictographs show the meaning of the character rather than the sound.

Xiàngxíng 象形 (shyahng-sheeng) (pictographs): These characters resemble the shape of the objects they represent, such as shān 山 (shahn) (mountain) or guī 龜 (gway) (the traditional character for turtle; the simplified character for turtle — 龟 — doesn’t really look as much like a turtle). Pictographs show the meaning of the character rather than the sound.

Biǎoyì or zhǐshì 表意 or 指事(byaow-ee or jir-shir) (ideographs): These characters represent more abstract concepts. The characters for shàng 上 (shahng) (above) and xià 下 (shyah) (below), for example, each have a horizontal line representing the horizon and another stroke leading out above or below the horizon.

Biǎoyì or zhǐshì 表意 or 指事(byaow-ee or jir-shir) (ideographs): These characters represent more abstract concepts. The characters for shàng 上 (shahng) (above) and xià 下 (shyah) (below), for example, each have a horizontal line representing the horizon and another stroke leading out above or below the horizon.

Huì yì 会意 (會意) (hway ee) (compound ideographs): These characters are combinations of simpler characters that together represent more things. For example, by combining the characters for sun (日) and moon (月), you get the character 明 míng (meeng), meaning bright.

Huì yì 会意 (會意) (hway ee) (compound ideographs): These characters are combinations of simpler characters that together represent more things. For example, by combining the characters for sun (日) and moon (月), you get the character 明 míng (meeng), meaning bright.

Xíngshēng 形声 (形聲) (sheeng-shuhng) (phonetic compounds): These characters are formed by two graphic elements — one hinting at the meaning of the word (called the radical; see the following section), and the other providing a clue to the sound. More than 90 percent of all Chinese characters are phonetic compounds.

Xíngshēng 形声 (形聲) (sheeng-shuhng) (phonetic compounds): These characters are formed by two graphic elements — one hinting at the meaning of the word (called the radical; see the following section), and the other providing a clue to the sound. More than 90 percent of all Chinese characters are phonetic compounds.

An example of a phonetic compound is the character gū 蛄 (goo). It’s a combination of the radical chóng 虫 (choong) (insect) and the sound element of the character gū 古 (goo) (ancient). Put them together, and you have the character 蛄, meaning cricket (the insect, not the sport). It’s pronounced with a first tone (gū) rather than a third tone (gŭ). So the sound of the word is similar to the term for ancient, even though that term has nothing to do with the meaning of the word. The actual meaning is connected to the radical referring to insects. Table 2-1 summarizes the Six Scripts.

The Chinese Radical: A Few Clues to a Character’s Meaning

What a radical idea! Two hundred and fourteen radical ideas, in fact.

冰 bīng (beeng) (ice)

冲 chōng (choong) (to pour boiling water on something/to rinse or flush)

汗 hàn (hahn) (sweat)

河 hé (huh) (river)

湖 hú (hoo) (lake)

Another example: The radical meaning wood — 木 mù (moo) — originally represented the shape of a tree with branches and roots). Here are some characters with the wood radical in them (also on the left-hand side):

板 bǎn (bahn) (board/plank)

林 lín (leen) (forest)

树 (樹) shù (shoo) (tree)

Sometimes you find the radical at the top of the character rather than on the left-hand side. The radical meaning rain — 雨 yú (yew) — is one such character. Look for the rain radical at the top these characters. (Hint: It looks slightly squished compared to the actual character for rain by itself.)

雹 bǎo (baow) (hail)

雷 léi (lay) (thunder)

露 lù (loo) (dew)

One of the most complicated radicals (number 214, to be precise) is the one that means nose: 鼻 bí (bee). It’s so complicated to write, in fact, that only one other character in the whole Chinese language uses it: 鼾 hān (hahn) (to snore).

Following the Rules of Stroke Order

If you want to study shū fǎ 书法 (書法) (shoo-fah) (calligraphy) with a traditional Chinese máo bǐ 毛笔 (毛筆) (maow-bee) (writing brush), or even just learn how to write Chinese characters with a plain old ballpoint pen, you need to know which stroke goes before the next. This progression is known as bǐ shùn 笔顺 (筆順) (bee shwun) (stroke order).

All those complicated-looking Chinese characters are actually created by several individual strokes of the Chinese writing brush. Bǐ shùn follows nine (count ’em) rules, which I lay out in the following sections.

Rule 1

The first rule of thumb is that you write the character by starting with the topmost stroke.

For example, among the first characters students usually learn is the number one, which is written with a single horizontal line: 一. Because this character is pretty easy and has only one stroke, it’s written from left to right.

The character for two has two strokes: 二. Both strokes are written from left to right; the top stroke is written first, following the top-to-bottom rule. The character for three has three strokes (三)and follows the same stroke-making pattern.

In the case of more complicated characters (for example, those with radicals that appear on the left-hand side), the radical on the left is written first, followed by the rest of the character. For example, to write the character meaning tree — 树 (樹) shù (shoo) — you first write the radical on the left (木) before adding the rest of the character to the right of the radical. To write the character meaning thunder — 雷 léi (lay) — you have to write the radical that appears on top (雨) first before writing the rest of the character underneath it.

Rules 2 through 9

Don’t worry; the remaining rules require a lot less explanation than rule 1 does:

Rule 2: Write horizontal strokes before vertical strokes. For example, the character meaning ten (十) is composed of two strokes, but the first one you write is the one appearing horizontally: 一. The vertical stroke downward is written after that.

Rule 2: Write horizontal strokes before vertical strokes. For example, the character meaning ten (十) is composed of two strokes, but the first one you write is the one appearing horizontally: 一. The vertical stroke downward is written after that.

Rule 3: Write strokes that have to pass through the rest of the character last. Vertical strokes that pass through many other strokes are written after the strokes they pass through (like in the second character for the city of Tiānjīn: 天津 [tyan-jeen]), and horizontal strokes that pass through all sorts of other strokes are written last (like in the character meaning boat: 舟 zhōu [joe]).

Rule 3: Write strokes that have to pass through the rest of the character last. Vertical strokes that pass through many other strokes are written after the strokes they pass through (like in the second character for the city of Tiānjīn: 天津 [tyan-jeen]), and horizontal strokes that pass through all sorts of other strokes are written last (like in the character meaning boat: 舟 zhōu [joe]).

Rule 4: Create diagonal strokes that go from right to left before writing the diagonal strokes that go from left to right. You write the character meaning culture — 文 wén (wuhn) — with four separate strokes: First comes the dot on top, then the horizontal line underneath it, then the diagonal stroke that goes from right to left, and finally the diagonal stroke that goes from left to right.

Rule 4: Create diagonal strokes that go from right to left before writing the diagonal strokes that go from left to right. You write the character meaning culture — 文 wén (wuhn) — with four separate strokes: First comes the dot on top, then the horizontal line underneath it, then the diagonal stroke that goes from right to left, and finally the diagonal stroke that goes from left to right.

Rule 5: In characters that are vertically symmetrical, create the center components before those on the left or the right. Then write the portion of the character appearing on the left before the one appearing on the right. An example of such a character is the one meaning to take charge of: 承 chéng (chuhng).

Rule 5: In characters that are vertically symmetrical, create the center components before those on the left or the right. Then write the portion of the character appearing on the left before the one appearing on the right. An example of such a character is the one meaning to take charge of: 承 chéng (chuhng).

Rule 6: Write the portion of the character that’s an outside enclosure before the inside portion, such as in the word for sun: 日rì (ir). Some characters with such enclosures don’t have bottom portions, such as with the character for moon: 月 yuè (yweh).

Rule 6: Write the portion of the character that’s an outside enclosure before the inside portion, such as in the word for sun: 日rì (ir). Some characters with such enclosures don’t have bottom portions, such as with the character for moon: 月 yuè (yweh).

Rule 7: Make the left vertical stroke of an enclosure first. For example, in the word meaning mouth — 口 kǒu (ko) — you write the vertical stroke on the left first, followed the horizontal line on top and the vertical stroke on the right (those two are written as one stroke) and finally the horizontal line on the bottom.

Rule 7: Make the left vertical stroke of an enclosure first. For example, in the word meaning mouth — 口 kǒu (ko) — you write the vertical stroke on the left first, followed the horizontal line on top and the vertical stroke on the right (those two are written as one stroke) and finally the horizontal line on the bottom.

Rule 8: Bottom enclosing components usually come last, such as with the character meaning the way: 道 (dào) (daow).

Rule 8: Bottom enclosing components usually come last, such as with the character meaning the way: 道 (dào) (daow).

Rule 9: Dots come last. For example, in the character meaning jade — 玉 yù (yew) — the little dot you see between the bottom and middle horizontal lines is written last.

Rule 9: Dots come last. For example, in the character meaning jade — 玉 yù (yew) — the little dot you see between the bottom and middle horizontal lines is written last.

Which Way Did Those Characters Go? Unraveling Character Order

Because each Chinese character can be a word in and of itself or part of a compound word, you can read and understand them in any order — right to left, left to right, or top to bottom. If you see a Chinese movie in Chinatown, you can often choose between two types of subtitles: English, which you read from left to right, on one line and Chinese characters, which you read from right to left, on another (usually; the Chinese line can also go from left to right, so be careful.) You may go cross-eyed for a while trying to follow them both.

Right to left and left to right are common enough, but why top to bottom, you may ask? Because before the invention of paper around the 8th century BCE, Chinese was originally written on pieces of bamboo, which required the vertical writing direction.

See whether you can tell what the following saying means, regardless of which way these characters are going. First, I tell you what the four characters each mean individually; then you can string them together and take a stab at the whole saying.

知 zhī (jir) (to know)

知 zhī (jir) (to know)

者 zhě (juh) (possessive article, such as the one who)

者 zhě (juh) (possessive article, such as the one who)

不 bù (boo) (negative prefix, such as no, not, doesn’t)

不 bù (boo) (negative prefix, such as no, not, doesn’t)

言 yán (yeahn) (classical Chinese for to speak)

言 yán (yeahn) (classical Chinese for to speak)

Okay, here’s the saying in three different directions. See whether you can figure it out by the time it’s written top to bottom.

Left to right: 知者不言, 言者不知

Right to left: 知不者言, 言不者知

Top to bottom:

知

者

不

言,

言

者

不

知

Give up? It means Those who know do not speak, and those who speak do not know. How’s that for wisdom?

Separating Traditional and Simplified Characters

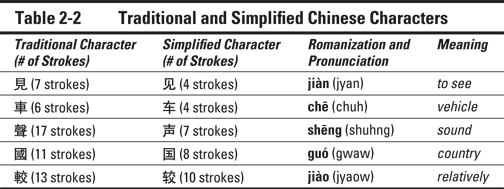

Whether you’re planning on visiting Taiwan or doing business in the People’s Republic of China, you need to know the difference between fántǐ zì 繁体字 (繁體字) (fahn-tee dzuh) (traditional characters) and jiántǐ zì 简体字 (簡體字) (jyan-tee dzuh) (simplified characters).

Fántǐ zì haven’t changed much since kǎi shū 楷书 (楷書) (kye shoo) (standard script) was first created around 200 CE. These traditional characters are still used in Taiwan, Hong Kong, Macao, and many overseas Chinese communities today, where the proud but arduous process of learning complicated characters begins at a very early age and the art of deftly wielding a Chinese writing brush comes with the territory.

Jiántǐ zì are used solely in the People’s Republic of China, Singapore, and Malaysia. When the People’s Republic of China was established in 1949, the illiteracy rate among the general populace was about 85 percent — in large part because learning to write Chinese was difficult, especially when most of the population consisted of farmers who had to work on the land from dawn to dusk.

The new Communist government decided to simplify the writing process by reducing the number of strokes in many characters. Table 2-2 shows you some examples of the before (traditional characters) and after (simplified characters).

Using a Chinese Dictionary . . . without an Alphabet!

Whether you’re looking at simplified or traditional characters (see the preceding section), you don’t find any letters stringing them together like you see in English. So how in the world do Chinese people consult a Chinese dictionary? (Bet you didn’t know I could read your mind.) In several different ways.

Count the number of strokes in the overall character. Because Chinese characters are composed of several strokes of the writing brush, one way to look up a character is by counting the number of strokes and then looking up the character under the portion of the dictionary that notes characters by strokes. But to do so, you have to know which radical to check under first.

Count the number of strokes in the overall character. Because Chinese characters are composed of several strokes of the writing brush, one way to look up a character is by counting the number of strokes and then looking up the character under the portion of the dictionary that notes characters by strokes. But to do so, you have to know which radical to check under first.

Determine the radical. Each radical is itself composed of a certain number of strokes, so you have to first look up the radical by the number of strokes it contains. After you locate that radical, you start looking under the number of strokes left in the character after that radical to locate the character you wanted to look up in the first place.

Determine the radical. Each radical is itself composed of a certain number of strokes, so you have to first look up the radical by the number of strokes it contains. After you locate that radical, you start looking under the number of strokes left in the character after that radical to locate the character you wanted to look up in the first place.

Check under the pronunciation of the character. You can always just check under the pronunciation of the character (assuming you already know how to pronounce it), but you have to sift through every single homonym (characters with the same pronunciation) to locate just the right one. You also have to look under the various tones to see which pronunciation comes with the first, second, third, or fourth tone you want to locate. And because Chinese has so many homonyms, this task isn’t as easy as it may sound (no pun intended). (You can read more about tones in Chapter 1).

Check under the pronunciation of the character. You can always just check under the pronunciation of the character (assuming you already know how to pronounce it), but you have to sift through every single homonym (characters with the same pronunciation) to locate just the right one. You also have to look under the various tones to see which pronunciation comes with the first, second, third, or fourth tone you want to locate. And because Chinese has so many homonyms, this task isn’t as easy as it may sound (no pun intended). (You can read more about tones in Chapter 1).

I bet now you feel really relieved that you’re only focusing on spoken Chinese and not the written language.

Fun & Games

Fun & Games

Fill in the blanks below to test your knowledge of the Chinese writing system. Refer to Appendix D for the correct answers.

1. The Chinese written language contains _____ radicals.

a) 862 b) 194 c) 214 d) 2,140

2. The origins of the Chinese writing system can be found on _____.

a) oracle bones b) bronze inscriptions c) chopped liver d) rice cakes

3. The direction of Chinese writing is _____.

a) right to left b) left to right c) top to bottom d) all of the above

4. The most complicated radical to write (鼻) means _____.

a) eye b) ear c) nose d) throat

5. Chinese characters that are simple line drawings representing an object are _____.

a) ideographs b) compound ideographs c) pictographs d) phonetic compounds

Chinese has the multiple distinction of being the mother tongue of the oldest continuous civilization on earth as well as the language spoken by the greatest number of people. It arguably has one the most intricate written languages in existence, with about 50,000 characters in a comprehensive Chinese dictionary. To read a newspaper with relative ease, though, you only need to know about 3,000 to 4,000 characters.

Chinese has the multiple distinction of being the mother tongue of the oldest continuous civilization on earth as well as the language spoken by the greatest number of people. It arguably has one the most intricate written languages in existence, with about 50,000 characters in a comprehensive Chinese dictionary. To read a newspaper with relative ease, though, you only need to know about 3,000 to 4,000 characters. The Chinese written language contains a total of 214

The Chinese written language contains a total of 214

You can see the role of bamboo strips in the character for

You can see the role of bamboo strips in the character for