Chapter 3

Warming Up with the Basics: Chinese Grammar

In This Chapter

Getting the hang of the parts of speech

Getting the hang of the parts of speech

Making statements negative or possessive

Making statements negative or possessive

Discovering how to ask questions

Discovering how to ask questions

Maybe you’re one of those people who cringe at the mere mention of the word grammar. Just the thought of all those rules on how to construct sentences can put you into a cold sweat.

Hey, don’t sweat it! This chapter can just as easily be called “Chinese without Tears.” It gives you some quick and easy shortcuts on how to combine the basic building blocks of Chinese (which, by the way, are the same components that make up English) — nouns to name things; adjectives to qualify the nouns; verbs to show action or passive states of being; and adverbs to describe the verbs, adjectives, or other adverbs. After you know how to combine these parts of any given sentence, you can express your ideas and interests spanning the past, present, and future.

When you speak English, I bet you don’t sit and analyze the word order before opening your mouth to say something. Well, the same can hold true when you begin speaking Chinese. You probably didn’t even know the word for grammar before someone taught you that it was the framework for analyzing the structure of a language. Instead of overwhelming you, this chapter makes understanding Chinese grammar as easy as punch.

If you’re patient with yourself, have fun following the dialogues illustrating basic sentences, and listen to them on the accompanying audio tracks, you’ll do just fine.

The Basics of Chinese Nouns, Articles, and Adjectives

Admit it. Most of us took the better part of our first two years of life to master the basics when it came to forming English sentences. With this book, you can whittle this same skill in Chinese down to just a few minutes. Just keep reading this chapter. I promise it’ll save you a lot of time in the long run.

The basic word order of Chinese is exactly the same as in English. Hard to imagine? Just think of it this way: When you say I love spinach, you’re using the subject (I), verb (love), object (spinach) sentence order. It’s the same in Chinese. Only in Beijing, the sentence sounds more like Wǒ xǐhuān bōcài. 我喜欢菠菜. (我喜歡菠菜.) (waw she-hwahn baw-tsye.).

And if that isn’t enough to endear you to Chinese, maybe these tidbits of information will:

You don’t need to distinguish between singular and plural nouns.

You don’t need to distinguish between singular and plural nouns.

You don’t have to deal with gender-specific nouns.

You don’t have to deal with gender-specific nouns.

You can use the same word as both the subject and the object.

You can use the same word as both the subject and the object.

You don’t need to conjugate verbs.

You don’t need to conjugate verbs.

You don’t need to master verb tenses. (Don’t you just love it already?)

You don’t need to master verb tenses. (Don’t you just love it already?)

How could such news not warm the hearts of all those who’ve had grammar phobia since grade school? I get to the verb-related issues later in the chapter; in this section, I pull you up to speed on nouns and their descriptors.

Nouns

Common nouns represent tangible things, such as háizi 孩子 (hi-dzuh) (child) or yè 叶(葉) (yeh) (leaf). Like all languages, Chinese is just chock-full of nouns:

Proper nouns for such things as names of countries or people, like Fǎguó 法国 (法國) (fah-gwaw) (France) and Zhāng Xiānshēng 张先生 (張先生) (jahng shyan-shung) (Mr. Zhang)

Proper nouns for such things as names of countries or people, like Fǎguó 法国 (法國) (fah-gwaw) (France) and Zhāng Xiānshēng 张先生 (張先生) (jahng shyan-shung) (Mr. Zhang)

Material nouns for such nondiscrete things as kāfēi 咖啡 (kah-fay) (coffee) or jīn 金 (jin) (gold)

Material nouns for such nondiscrete things as kāfēi 咖啡 (kah-fay) (coffee) or jīn 金 (jin) (gold)

Abstract nouns for such things as zhèngzhì 政治 (juhng-jir) (politics) or wénhuà 文化 (one-hwah) (culture)

Abstract nouns for such things as zhèngzhì 政治 (juhng-jir) (politics) or wénhuà 文化 (one-hwah) (culture)

Pronouns

Pronouns are easy to make plural in Chinese. Just add the plural suffix -men to the three basic pronouns:

Wǒ 我 (waw) (I/me) becomes wǒmen 我们 (我們) (waw-mun) (we/us).

Wǒ 我 (waw) (I/me) becomes wǒmen 我们 (我們) (waw-mun) (we/us).

Nǐ 你 (nee) (you) becomes nǐmen 你们 (你們) (nee-mun) (you [plural]).

Nǐ 你 (nee) (you) becomes nǐmen 你们 (你們) (nee-mun) (you [plural]).

Tā 他/她/它 (tah) (he/him, she/her, it) becomes tāmen 他们/她们/它们 (他們/她們/它們) (tah-mun) (they/them).

Tā 他/她/它 (tah) (he/him, she/her, it) becomes tāmen 他们/她们/它们 (他們/她們/它們) (tah-mun) (they/them).

Classifiers

Classifiers are sometimes called measure words, even though they don’t really measure anything. They actually help classify particular nouns. For example, the classifier běn 本 (bun) can refer to books, magazines, dictionaries, and just about anything else that’s printed and bound like a book. You may hear Wǒ yào yìběn shū. 我要一本书. (我要一本書.) (waw yaow ee-bun shoo.) (I want a book.) just as easily as you hear Wǒ yào kàn yìběn zázhì. 我要看一本杂志. (我要看一本雜志.) (waw yaow kahn ee-bun dzah-jir.) (I want to read a magazine.).

Classifiers are found between a number (or a demonstrative pronoun such as this or that) and a noun. They’re similar to English words such as herd (of elephants) or school (of fish). Although English doesn’t use classifiers too often, in Chinese you find them wherever a number is followed by a noun, or at least an implied noun (such as I’ll have another one, referring to a cup of coffee).

Chinese has lots of different classifiers because they’re each used to refer to different types of things. For example, Table 3-1 lists classifiers for natural objects. Here are some other examples:

gēn 根 (gun): Used for anything that looks like a stick, such as a string or even a blade of grass

gēn 根 (gun): Used for anything that looks like a stick, such as a string or even a blade of grass

zhāng 张 (張) (jahng): Used for anything with a flat surface, such as a newspaper, table, or bed

zhāng 张 (張) (jahng): Used for anything with a flat surface, such as a newspaper, table, or bed

kē 颗 (顆) (kuh): Used for anything round and tiny, such as a pearl

kē 颗 (顆) (kuh): Used for anything round and tiny, such as a pearl

Table 3-1 Typical Classifiers for Natural Objects

|

Classifier |

Pronunciation |

Use |

|

duǒ 朵 |

dwaw |

flowers |

|

kē 棵 |

kuh |

trees |

|

lì 粒 |

lee |

grain (of rice, sand, and so on) |

|

zhī 只(隻) |

jir |

animals, insects, birds |

|

zuò 座 |

dzwaw |

hills, mountains |

Whenever you have a pair of anything, you can use the classifier shuāng 双(雙) (shwahng). That goes for yì shuāng kuàizi 一双筷子 (一雙筷子) (ee shwahng kwye-dzuh) (a pair of chopsticks) as well as for yì shuāng shǒu 一双手 (一雙手) (ee shwahng show) (a pair of hands). Sometimes a pair is indicated by the classifier duì 对 (對) (dway), as in yí duì ěrhuán 一对耳环 (一對耳環) (ee dway are-hwahn) (a pair of earrings).

Singular and plural: It’s a non-issue

Chinese makes no distinction between singular and plural. If you say the word shū 书 (書) (shoo), it can mean book just as easily as books. The only way you know whether it’s singular or plural is if a number followed by a classifier precedes the word shū, as in Wǒ yǒu sān běn shū. 我有三本书. (我有三本書.) (waw yo sahn bun shoo.) (I have three books.).

Talkin’ the Talk

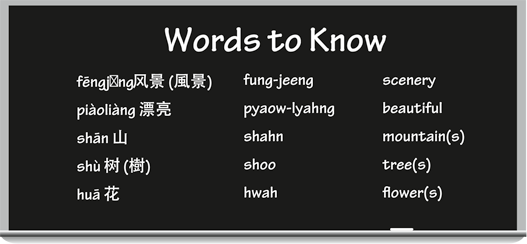

Susan and Michael are looking at a beautiful field.

Susan:

Zhèr de fēngjǐng zhēn piàoliàng!

jar duh fung-jeeng juhn pyaow-lyahng.

This scenery is really beautiful!

Michael:

Nǐ kàn! Nà zuò shān yǒu nàmme duō shù, nàmme duō huā.

nee kahn! nah dzwaw shahn yo nummuh dwaw shoo, nummuh dwaw hwah.

Look! That mountain has so many trees and flowers.

Susan:

Duì le. Nèi kē shù tèbié piàoliàng. Zhè duǒ huā yě hěn yǒu tèsè.

dway luh. nay kuh shoo tuh-byeh pyaow-lyahng. jay dwaw hwah yeah hun yo tuh-suh.

You’re right. That tree is particularly beautiful. And this flower is also really unique.

Michael:

Nà kē shù shàng yě yǒu sān zhī niǎo.

nah kuh shoo shahng yeah yo sahn jir nyaow.

That tree also has three birds in it.

Definite versus indefinite articles

If you’re looking for those little words in Chinese you can’t seem to do without in English, such as a, an, and the — articles, as grammarians call them — you’ll find they simply don’t exist in Chinese. The only way you can tell if something is being referred to specifically (hence, considered definite) or just generally (and therefore indefinite) is by the word order. Nouns that refer specifically to something are usually found at the beginning of the sentence, before the verb:

Háizimen xǐhuān tā. 孩子们喜欢她. (孩子們喜歡她.) (hi-dzuh-mun she-hwahn tah.) (The children like her.)

Pánzi zài zhuōzishàng. 盘子在桌子上. (盤子在桌子上.) (pahn-dzuh dzye jwaw-dzuh-shahng.) (There’s a plate on the table.)

Shū zài nàr. 书在那儿. (書在那兒.) (shoo dzye nar.) (The book[s] are there.)

Nouns that refer to something more general (and are therefore indefinite) can more often be found at the end of the sentence, after the verb:

Nǎr yǒu huā? 哪儿有花? (哪兒有花?) (nar yo hwah?) (Where are some flowers?/Where is there a flower?)

Nàr yǒu huā. 那儿有花. (那兒有花.) (nar yo hwah.) (There are some flowers over there./There’s a flower over there.)

Zhèige yǒu wèntí. 这个有问题. (這個有問題.) (jay-guh yo one-tee.) (There’s a problem with this./There are some problems with this.)

Xióngmāo shì dòngwù. 熊猫是动物. (熊貓是動物.) (shyoong-maow shir doong-woo.) (Pandas are animals.)

Same thing goes if an adjective comes after the noun, such as

Pútáo hěn tián. 葡萄很甜. (poo-taow hun tyan.) (Grapes are very sweet.)

Or if there’s an auxiliary verb, such as

Xiǎo māo huì zhuā lǎoshǔ. 小貓会抓老鼠. (小貓會抓老鼠.) (shyaow maow hway jwah laow-shoo.) (Kittens can catch mice.)

Or a verb indicating that the action occurs habitually, such as

Niú chī cǎo. 牛吃草. (nyo chir tsaow.) (Cows eat grass.)

Nouns that are preceded by a numeral and a classifier, especially when the word dōu 都 (doe) (all) exists in the same breath, are also considered definite:

Sìge xuéshēng dōu hěn cōngmíng. 四个学生都很聪明. (四個學生都很聰明.) (suh-guh shweh-shung doe hun tsoong-meeng.) (The four students are all very smart.)

If the word yǒu 有 (yo) (to exist) comes before the noun and is then followed by a verb, it can also mean the reference is indefinite:

Yǒu shū zài zhuōzishàng. 有书在桌子上. (有書在桌子上.) (yo shoo dzye jwaw-dzuh-shahng.) (There are books on top of the table.)

If you see the word zhè 这 (這) (juh) (this) or nà 那 (nah) (that), plus a classifier used when a noun comes after the verb, it indicates a definite reference:

Wǒ yào mǎi nà zhāng huà. 我要买那张画. (我要買那張畫.) (waw yaow my nah jahng hwah.) (I want to buy that painting.)

Adjectives

As you learned in grade school (you were paying close attention, weren’t you?), adjectives describe nouns. The question is where to put them. The general rule of thumb in Chinese is that if the adjective is pronounced with only one syllable, it appears immediately in front of the noun it qualifies:

cháng zhītiáo 长枝条 (長枝 條) (chahng jir-tyaow) (long stick)

lǜ chá 绿茶 (綠茶) (lyew chah) (green tea)

If the adjective has two syllables, though, the possessive particle de 的 (duh) comes between it and whatever it qualifies:

cāozá de wǎnhuì 嘈杂的晚会 (嘈雜的晚會) (tsaow-dzah duh wahn-hway) (noisy party)

gānjìng de yīfu 干净的衣服 (乾淨的衣服) (gahn-jeeng duh ee-foo) (clean clothes)

And if a numeral is followed by a classifier, those should both go in front of the adjective and what it qualifies:

sān běn yǒuyìsī de shū 三本有意思的书 (三本有意思的書) (sahn bun yo-ee-suh duh shoo) (three interesting books)

yí jiàn xīn yīfu 一件新衣服 (一件新服裝) (ee jyan shin ee-foo) (a [piece of] new clothing)

Nà jiàn yīfu tài jiù. 那件衣服太旧. (那件衣服太舊.) (nah jyan ee-foo tye jyoe.) (That piece of clothing [is] too old.)

Tā de fángzi hěn gānjìng. 他的房子很干净. (他的房子很乾淨.) (tah duh fahng-dzuh hun gahn-jeeng.) (His house [is] very clean.)

Getting Into Verbs, Adverbs, Negation, and Possession

The following sections give you the lowdown on verbs, their friends the adverbs, and ways you can negate statements and express possession.

Verbs

Good news! You never have to worry about conjugating a Chinese verb in your entire life! If you hear someone say Tāmen chī Yìdàlì fàn. 他们吃意大利饭. (他們吃意大利飯.) (tah-men chir ee-dah-lee fahn.), it may mean They eat Italian food. just as easily as it may mean They’re eating Italian food. Table 3-2 presents some common verbs; check out Appendix B for a more extensive list.

Table 3-2 Common Chinese Verbs

|

Chinese |

Pronunciation |

English |

|

chī 吃 |

chir |

to eat |

|

kàn 看 |

kahn |

to see |

|

mǎi 买 (買) |

my |

to buy |

|

mài 卖 (賣) |

my |

to sell |

|

rènshi 认识 (認識) |

run-shir |

to know (a person) |

|

shì 是 |

shir |

to be |

|

yào 要 |

yaow |

to want/to need |

|

yǒu 有 |

yo |

to have |

|

zhīdào 知道 |

jir-daow |

to know (a fact) |

|

zǒu lù 走路 |

dzoe loo |

to walk |

|

zuò fàn 做饭 (做飯) |

dzwaw fahn |

to cook |

To be or not to be: The verb shì

Does the Chinese verb shì 是 (shir) really mean to be? Or is it not to be? Shì is indeed similar to English in usage because it’s often followed by a noun that defines the topic, such as Tā shì wǒde lǎobǎn. 他是我的老板. (他是我的老闆.) (tah shir waw-duh laow-bahn.) (He’s my boss.) or Nà shì yīge huài huà. 那是一个坏话. (那是一個壞 話.) (nah shir ee-guh hwye hwah.) (That’s a bad word.).

Shì bú shì? 是不是? (shir boo shir?) (Is it or isn’t it?)

Zhè bú shì táng cù yú. 这不是糖醋鱼. (這不是糖醋魚.) (jay boo shir tahng tsoo yew.) (This isn’t sweet and sour fish.).

Flip to the later section “Bù and méiyǒu: Total negation” for more on negation prefixes.

Feeling tense? Le, guò, and other aspect markers

Okay, you can relax now. No need to get tense about Chinese, because verbs don’t indicate tenses all by themselves. That’s the job of aspect markers, which are little syllables that indicate whether an action has been completed, is continuing, has just begun, and just about everything in between.

Take the syllable le 了 (luh), for example. If you use it as a suffix to a verb, it can indicate that an action has been completed:

Nǐ mǎi le hěn duō shū. 你买了很多书. (你買了很多書.) (nee my luh hun dwaw shoo.) (You bought many books.)

Tā dài le tāde yǔsǎn. 他带了他的雨伞. (他帶了他的雨傘.) (tah dye luh tah-duh yew-sahn.) (He brought his umbrella.)

And if you want to turn the sentence into a question, just add méiyǒu 没有 (mayo) at the end. It automatically negates the action completed by le:

Nǐ mǎi le hěn duō shū méiyǒu? 你买了很多书没有? (你買了很多書没有? (nee my luh hun dwaw shoo mayo?) (Have you bought many books?/Did you buy many books?)

Tā dài le tāde yǔsǎn méiyǒu? 他带了他的雨伞没有? (他帶了他的雨傘没有?) (tah dye luh tah-duh yew-sahn mayo?) (Did he bring his umbrella?)

Another aspect marker is guò 过 (過) (gwaw). It basically means that something has been done at one point or another even though it’s not happening right now:

Tā qù guò Měiguó. 他去过美国. (他去過美國.) (ta chyew gwaw may-gwaw.) (He has been to America.)

Wǒmen chī guò Fǎguó cài. 我们吃过法国菜. (我們吃過法國菜.) (waw-mun chir gwaw fah-gwaw tsye.) (We have eaten French food before.)

If an action is happening just as you speak, you use the aspect marker zài 在 (dzye):

Nǐ māma zài zuòfàn. 你妈妈在做饭. (你媽媽在做飯.) (nee mah-mah dzye dzwaw-fahn.) (Your mother is cooking.)

Wǒmen zài chīfàn. 我们在吃饭. (我們在吃飯.) (waw-mun dzye chir-fahn.) (We are eating.)

If something is or was happening continually and resulted from something else you did, just add the syllable zhe 着 (juh) to the end of the verb to say things like the following:

Nǐ chuān zhe yí jiàn piàoliàng de chènshān. 你穿着一件漂亮的衬衫. (你穿著一件漂亮的襯衫.) (nee chwan juh ee jyan pyaow-lyahng duh chuhn-shahn.) (You’re wearing a pretty shirt.)

Tā dài zhe yíge huáng màozi. 他戴着一个黄帽子. (他戴著一個黃帽子.) (tah dye juh ee-guh hwahng maow-dzuh.) (He’s wearing a yellow hat.)

Another way you can use zhe is when you want to indicate two actions occurring at the same time:

Tā zuò zhe chīfàn. 她坐着吃饭. (她坐著吃飯.) (tah dzwaw juh chir-fahn.) (She is/was sitting there eating.)

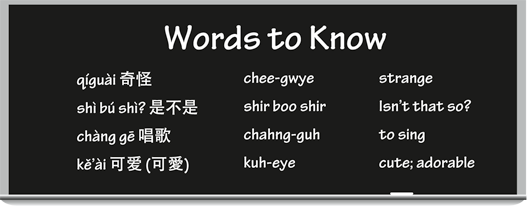

Talkin’ the Talk

Carol and Joe have fun people-watching on the streets of Shanghai.

Carol:

Nǐ kàn! Nàge xiǎo háizi dài zhe yíge hěn qíguài de màozi, shì bú shì?

nee kahn! nah-guh shyaow hi-dzuh dye juh ee-guh hun chee-gwye duh maow-dzuh, shir boo shir?

Look! That little kid is wearing a really strange hat, isn’t she?

Joe:

Duì le. Tā hái yìbiān zǒu, yìbiān chàng gē.

dway luh. tah hi ee-byan dzoe, ee-byan chahng guh.

Yeah. She’s also singing while she walks.

Carol:

Wǒ méiyǒu kàn guò nàmme kě’ài de xiǎo háizi.

waw mayo kahn gwaw nummuh kuh-eye duh shyaow hi-dzuh.

I’ve never seen such a cute child.

Joe:

Zài Zhōngguó nǐ yǐjīng kàn le tài duō kě’ài de xiǎo háizi.

dzye joong-gwaw nee ee-jeeng kahn luh tye dwaw kuh-eye duh shyaow hi-dzuh.

You’ve already seen too many adorable little kids in China.

The special verb: Yǒu (to have)

Do you yǒu 有 (yo) a computer? No?! Too bad. Everyone else seems to have one these days. How about a sports car? Do you yǒu one of those? If not, welcome to the club. People who have lots of things use the word yǒu pretty often, translated as to have like in the following examples:

Wǒ yǒu sānge fángzi: yíge zài Ōuzhōu, yíge zài Yàzhōu, yíge zài Měiguó. 我有三个房子: 一个在欧洲, 一个在亚洲, 一个在美国. (我有三個房子: 一個在歐洲, 一個在亞洲, 一個在美國.) (waw yo sahn-guh fahng-dzuh: ee-guh dzye oh-joe, ee-guh dzye yah-joe, ee-guh dzye may-gwaw.) (I have three homes: one in Europe, one in Asia, and one in America.)

Wǒ yǒu yí wàn kuài qián. 我有一万块钱. (我有一萬塊錢.) (waw yo ee wahn kwye chyan.) (I have $10,000.)

Another way yǒu can be translated is as there is or there are:

Yǒu hěn duō háizi. 有很多孩子. (yo hun dwaw hi-dzuh.) (There are many children.), as opposed to Wǒ yǒu hěn duō háizi. 我有很多孩子. (waw yo hun dwaw hi-dzuh.) (I have many children.)

Shūzhuōshàng yǒu wǔ zhāng zhǐ. 书桌上有五张纸. (書桌上有五張紙.) (shoo-jwaw-shahng yo woo jahng jir.) (There are five pieces of paper on the desk.)

Méiyǒu hěn duō háizi. 沒有很多孩子. (mayo hun dwaw hi-dzuh.) (There aren’t many children.)

Shūzhuōshàng méiyǒu wǔ zhāng zhǐ. 书桌上沒有五张纸. (書桌上沒有五張紙.) (shoe-jwaw-shahng mayo woo jahng jir.) (There aren’t five pieces of paper on the desk.)

You can read more about negation prefixes in “Bù and méiyǒu: Total negation” later in the chapter.

Asking for what you want: The verb yào

After Yao Ming, the 7-foot-6-inch basketball superstar from China, came on the scene, the verb yào 要 (yaow) (to want) got some great publicity in the United States. The character for his name isn’t written quite the same as the verb yào, but at least everyone knows how to pronounce it already: yow!

Yào is one of the coolest verbs in Chinese. When you say it, you usually get what you want. In fact, the mere mention of the word yào means you want something:

Wǒ yào gēn nǐ yìqǐ qù kàn diànyǐng. 我要跟你一起去看电影. (我要跟你一起去看電影.) (waw yaow gun nee ee-chee chyew kahn dyan-yeeng.) (I want to go to the movies with you.)

Wǒ yào yì bēi kāfēi. 我要一杯咖啡. (waw yaow ee bay kah-fay.) (I want a cup of coffee.)

Nǐ yào xiǎoxīn! 你要小心! (nee yaow shyaow-sheen!) (You should be careful!)

Nǐ yào xǐ shǒu. 你要洗手. (nee yaow she show.) (You need to wash your hands.)

Adverbs

Adverbs serve to modify verbs or adjectives and always appear in front of them in Chinese. The most common adverbs you find in Chinese are hěn 很 (hun) (very) and yě 也 (yeah) (also).

Bù and méiyǒu: Total negation

Boo! Scare you? Don’t worry. I’m just being negative in Chinese. That’s right: The word bù is pronounced the same way a ghost would say it (boo) and is often spoken with the same intensity.

Bù can negate something you’ve done in the past or the present (or at least indicate you don’t generally do it these days), and it can also help negate something in the future:

Diànyǐngyuàn xīngqīliù bù kāimén. 电影院星期六不开门. (電影院星期六不開門.) (dyan-yeeng-ywan sheeng-chee-lyo boo kye-mun.) (The movie theatre won’t be open on Saturday.)

Tā xiǎo de shíhòu bù xǐhuān chī shūcài. 他小的时候不喜欢吃蔬菜. (他小的時候不喜歡吃蔬菜.) (tah shyaow duh shir-ho boo she-hwahn chir shoo-tsye.) (When he was young, he didn’t like to eat vegetables.)

Wǒ bú huà huàr. 我不画画儿. (我不畫畫兒.) (waw boo hwah hwar.) (I don’t paint.)

Wǒ búyào chàng gē. 我不要唱歌. (waw boo-yaow chahng guh.) (I don’t want to sing.)

In addition to being part of the question yǒu méiyǒu (do you have/did it), méiyǒu is another negative prefix that also goes before a verb. It refers only to the past, though, and means either something didn’t happen, or at least didn’t happen on a particular occasion:

Wǒ méiyǒu kàn nèi bù diànyǐng. 我没有看那部电影. (我沒有看那部電影.) (waw mayo kahn nay boo dyan-yeeng.) (I didn’t see that movie.)

Zuótiān méiyǒu xiàyǔ. 昨天没有下雨. (昨天沒有下雨.) (dzwaw-tyan mayo shyah-yew.) (It didn’t rain yesterday.)

If the aspect marker guò is at the end of the verb méiyǒu, it means the action never happened (up until now) in the past. By the way, you’ll sometimes find that méiyǒu is shortened just to méi:

Wǒ méi qù guò Fǎguó. 我没去过法国. (我沒去過法國.) (waw may chyew gwaw fah-gwaw.) (I’ve never been to France.)

Wǒ méi chī guò Yìndù cài. 我没吃过印度菜. (我沒吃過印度菜.) (wo may chir gwaw een-doo tsye.) (I’ve never eaten Indian food.)

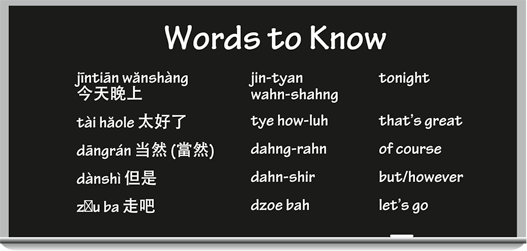

Talkin’ the Talk

Harvey:

Nǐmen jīntiān wǎnshàng yào búyào qù fànguǎn chīfàn?

nee-mun jin-tyan wahn-shahng yaow boo-yaow chyew fahn-gwahn chir-fahn?

Do you both want to go to a restaurant tonight?

Stella:

Nà tài hǎole. Dāngrán yào.

nah tye how-luh. dahng-rahn yaow.

That’s a great idea. Of course I’d like to go.

Laurie:

Wǒ búyào. Wǒ méiyǒu qián.

waw boo-yaow. waw mayo chyan.

I don’t want to. I have no money.

Harvey:

Wǒ yě méiyǒu qián, dànshì méiyǒu guānxi. Wǒ zhīdào yíge hěn hǎo, hěn piányì de Zhōngguó fànguǎn.

waw yeah mayo chyan, dahn-shir mayo gwahn-she. waw jir-daow ee-guh hun how, hun pyan-yee duh joong-gwaw fahn-gwan.

I don’t have any money either, but it doesn’t matter. I know a great but very inexpensive Chinese restaurant.

Laurie:

Hǎo ba. Zánmen zǒu ba.

how bah. dzah-men dzoe bah.

Okay. Let’s go.

Getting possessive with the particle de

The particle de 的 is ubiquitous in Chinese. Wherever you turn, there it is. Wǒde tiān! 我的天! (waw-duh tyan) (My goodness!) Oops . . . there it is again. It’s easy to use. All you have to do is attach it to the end of the pronoun, such as nǐde chē 你的车 (你的車) (nee-duh chuh) (your car), or other modifier, such as tā gōngsī de jīnglǐ 他公司的经理 (他公司的經理) (tah goong-suh duh jeeng-lee) (his company’s manager), and — voilà — it indicates possession.

Asking Questions

You have a few easy ways to ask questions in Chinese at your disposal. Hopefully you’re so curious about the world around you these days that you’re itching to ask lots of questions when you know how. I break them down in the following sections.

The question particle ma

By far the easiest way to ask a question is simply to end any given statement with a ma. That automatically makes it into a question. For example, Tā chīfàn. 他吃饭. (他吃飯.) (tah chir-fahn.) (He’s eating./He eats.) becomes Tā chīfàn ma? 他吃饭吗? (他吃飯嗎?) (tah chir-fahn mah?) (Is he eating?/Does he eat?) Nǐ shuō Zhōngwén. 你说中文. (你說中文.) (nee shwaw joong-one.) (You speak Chinese.) becomes Nǐ shuō Zhōngwén ma? 你说中文吗? (你說中文嗎?) (nee shwaw joong-one mah?) (Do you speak Chinese?)

Yes/no choice questions using bù between repeating verbs

Another way you can ask a Chinese question is to repeat the verb in its negative form. The English equivalent is to say something like Do you eat, not eat? Remember: This format can be used for only yes-or-no questions, though. Here are some examples:

Nǐ shì búshì Zhōngguórén? 你是不是中国人? (你是不是中國人?) (nee shir boo-shir joong-gwaw-run?) (Are you Chinese?)

Tāmen xǐhuān bùxǐhuān chī Zhōngguó cài? 他们喜欢不喜欢吃中国菜? (他們喜歡不喜歡吃中國菜?) (tah-men she-hwahn boo-she-hwahn chir joong-gwaw tsye?) (Do they like to eat Chinese food?)

Tā yào búyào háizi? 他要不要孩子? (tah yaow boo-yaow hi-dzuh?) (Does he want children?)

To answer this type of question, all you have to do is omit either the positive verb or the negative prefix and the verb following it:

Nǐ hǎo bù hǎo? 你好不好? (nee how boo how?) (How are you? [Literally: Are you good or not good?])

Wǒ hǎo. 我好. (waw how.) (I’m okay.) or Wǒ bùhǎo. 我不好. (waw boo-how.) (I’m not okay.)

Interrogative pronouns

A third way to ask questions in Chinese is to use interrogative pronouns. The following are pronouns that act as questions in Chinese:

nǎ 哪 (nah) + classifier (which)

nǎ 哪 (nah) + classifier (which)

nǎr 哪儿 (哪 兒) (nar) (where)

nǎr 哪儿 (哪 兒) (nar) (where)

shéi 谁 (誰) (shay) (who/whom)

shéi 谁 (誰) (shay) (who/whom)

shéi de 谁 的 (誰 的) (shay duh) (whose)

shéi de 谁 的 (誰 的) (shay duh) (whose)

shénme 什么 (甚麼) (shummuh) (what)

shénme 什么 (甚麼) (shummuh) (what)

shénme dìfāng 什么地方 (甚麼地方) (shummah dee-fahng) (where)

shénme dìfāng 什么地方 (甚麼地方) (shummah dee-fahng) (where)

Figuring out where such interrogative pronouns should go in any given sentence is easy. Just put them wherever the answer would be found. For example

Question: Nǐ shì shéi? 你是谁? (你是誰?) (nee shir shay?) (Who are you?)

Answer: Nǐ shì wǒ péngyǒu. 你是我朋友. (nee shir waw puhng-yo.) (You’re my friend.)

Question: Tāde nǚpéngyǒu zài nǎr? 他的女朋友在哪儿? (他的女朋友在哪兒?) (tah duh nyew-puhng-yo dzye nar?) (Where is his girlfriend?)

Answer: Tāde nǔpéngyǒu zài jiālǐ. 他的女朋友在家里. (他的女朋友在家裡.) (tah-duh nyew-puhng-yo dzye jyah-lee.) (His girlfriend is at home.)

Fun & Games

Fun & Games

Match the Chinese questions with the English translations. (See Appendix D for the correct answer.)

|

1. Shì bú shì? 是不是? |

a. Who are you? |

|

2. Nǐ shuō Zhōngwén ma? 你说中文吗? (你說中文嗎?) |

b. Isn’t that so? |

|

3. Nǐ shì shéi? 你是谁? (你是誰?) |

c. Do you have a laptop? |

|

4. Nà yǒu shénme guānxi? 那有什么关系? (那有甚麼關係?) |

d. Who cares? |

|

5. Nǐ yǒu méiyǒu yíge shǒutíshì? 你有没有一个手提式? (你有沒有一個手提式?) |

e. Do you speak Chinese? |

The way you can tell how one part of a Chinese sentence relates to another is generally by the use of particles and what form the word order takes. (

The way you can tell how one part of a Chinese sentence relates to another is generally by the use of particles and what form the word order takes. ( When you’re speaking to an elder or someone you don’t know too well and the person is someone to whom you should show respect, you need to use the pronoun

When you’re speaking to an elder or someone you don’t know too well and the person is someone to whom you should show respect, you need to use the pronoun  Never attach the suffix

Never attach the suffix  These rules have some exceptions: If you find a noun at the beginning of a sentence, it may actually refer to something indefinite if the sentence makes a general comment (instead of telling a whole story), like when you see the verb

These rules have some exceptions: If you find a noun at the beginning of a sentence, it may actually refer to something indefinite if the sentence makes a general comment (instead of telling a whole story), like when you see the verb