Chapter 13

Recreation and Outdoor Activities

In This Chapter

Talking about your hobbies

Talking about your hobbies

Appreciating Mother Nature

Appreciating Mother Nature

Pretending to be Picasso

Pretending to be Picasso

Creating your own tunes

Creating your own tunes

Exercising as an athlete

Exercising as an athlete

After a hard day at work, most people are ready to kick back and relax. But where to begin? Do you feel so consumed by your gōngzuò 工作 (goong-dzwaw) (work) that you can’t seem to switch gears? Get a life! Better yet, get a yèyú àihào 业余爱好 (業餘愛好) (yeh-yew eye-how) (hobby). Play some yīnyuè 音乐 (音樂) (yeen-yweh) (music) on your xiǎotíqín 小提琴 (shyaow-tee-cheen) (violin). Paint a huà 画 (畫) (hwah) (picture). Kick a zúqiú 足球 (dzoo-chyo) (football) around. Do whatever it takes to make you relax and have some fun. Your outside interests make you more interesting to be around, and you make new friends at the same time — especially if you join a duì 队 (隊) (dway) (team).

And if you’re into lánqiú 篮球 (籃球) (lahn-chyo) (basketball), just utter the name Yao Ming 姚明 (yaow meeng); you’ll instantly discover hordes of potential language exchange partners from among the many fans of this 7-foot-6-inch Shanghai native who made it big as a Houston Rockets superstar.

Naming Your Hobbies

Are you someone who likes to collect stamps, play chess, or watch birds in the park? Whatever you enjoy doing, your hobbies are always a good conversation piece. Having at least one yèyú àihào 业余爱好 (業餘愛好) (yeh-yew eye-how) (hobby) is always a good thing. How about getting involved in some of the following?

guān niǎo (gwan-nyaow) 观鸟 (觀鳥) (birdwatching)

guān niǎo (gwan-nyaow) 观鸟 (觀鳥) (birdwatching)

jí yóu 集邮 (集郵) (jee-yo) (stamp collecting)

jí yóu 集邮 (集郵) (jee-yo) (stamp collecting)

diàoyú 钓鱼 (釣魚) (dyaow-yew) (fishing)

diàoyú 钓鱼 (釣魚) (dyaow-yew) (fishing)

kàn shū 看书 (看書) (kahn shoo) (reading)

kàn shū 看书 (看書) (kahn shoo) (reading)

pēngtiáo 烹调 (烹調) (pung-tyaow) (cooking)

pēngtiáo 烹调 (烹調) (pung-tyaow) (cooking)

yuányì 园艺 (園藝) (ywan-ee) (gardening)

yuányì 园艺 (園藝) (ywan-ee) (gardening)

Nǐ huì búhuì dǎ tàijíquán? 你会不会打太极拳? (你會不會打太極拳?) (nee hway boo-hway dah tye-jee-chwahn?) (Do you know how to do Tai Ji?)

Nǐ huì búhuì dǎ tàijíquán? 你会不会打太极拳? (你會不會打太極拳?) (nee hway boo-hway dah tye-jee-chwahn?) (Do you know how to do Tai Ji?)

Nǐ dǎ májiàng ma? 你打麻将吗? (你打麻將嗎?) (nee dah mah-jyahng mah?) (Do you play mah-jong?)

Nǐ dǎ májiàng ma? 你打麻将吗? (你打麻將嗎?) (nee dah mah-jyahng mah?) (Do you play mah-jong?)

Talkin’ the Talk

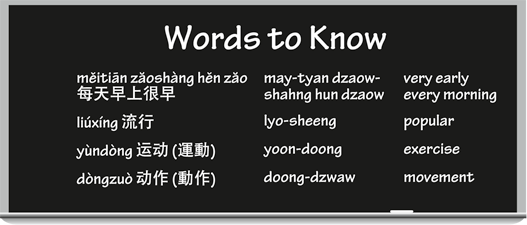

Donald and Helga discuss their knowledge of taijiquan with each other.

Donald:

Nǐ huì búhuì dǎ tàijíquán?

nee hway boo-hway dah tye-jee-chwan?

Do you know how to do Tai Ji?

Helga:

Búhuì. Kěshì wǒ zhīdào tàijíquán shì yì zhǒng hěn liúxíng de jiànshēn yùndòng.

boo-hway. kuh-shir waw jir-daow tye-jee-chwan shir ee joong hun lyo-sheeng duh jyan-shun yoon-doong.

No, but I know that Tai Ji is a very popular kind of exercise.

Donald:

Duìle. Měitiān zǎoshàng hěn zǎo hěn duō rén yìqǐ dǎ tàijíquán.

dway-luh. may-tyan dzaow-shahng hun dzaow hun dwaw run ee-chee dah tye-jee-chwan.

That’s right. Very early every morning, lots of people practice Tai Ji together.

Helga:

Tàijíquán de dòngzuò kànqǐlái hěn màn.

tye-jee-chwan duh doong-dzwaw kahn-chee-lye hun mahn.

Tai Ji movements look very slow.

Donald:

Yòu shuō duìle! Shēntǐ zǒngshì yào wěndìng. Dòngzuò zǒngshì yào xiétiáo.

yo shwaw dway-luh! shun-tee dzoong-shir yaow one-deeng. doong-dzwaw dzoong-shir yaow shyeh-tyaow.

Right again! The body should always be stable, and the movements should always be well coordinated.

Exploring Nature

If you’re working overseas in China and want to get really far from the madding crowds, or even just far enough away from your bàngōngshì 办公室 (辦公室) (bahn-goong-shir) (office) to feel refreshed, try going to one of China’s many sacred mountains or a beautiful beach to take in the shānshuǐ 山水 (shahn-shway) (landscape). You may want to qù lùyíng 去露营 (去露營) (chyew lyew-eeng) (go camping) or set up camp on the beach and have a yěcān 野餐 (yeh-tsahn) (picnic) before you pá shān 爬山 (pah shahn) (climb a mountain).

bǎotǎ 宝塔 (寶塔) (baow-tah) (pagoda)

bǎotǎ 宝塔 (寶塔) (baow-tah) (pagoda)

dàomiào 道庙 (道廟) (daow-meow) (Daoist temple)

dàomiào 道庙 (道廟) (daow-meow) (Daoist temple)

dàotián 稻田 (daow-tyan) (rice paddies)

dàotián 稻田 (daow-tyan) (rice paddies)

fómiào 佛庙 (佛廟) (faw-meow) (Buddhist temple)

fómiào 佛庙 (佛廟) (faw-meow) (Buddhist temple)

kǒngmiào 孔庙 (孔廟) (koong-meow) (Confucian temple)

kǒngmiào 孔庙 (孔廟) (koong-meow) (Confucian temple)

miào 庙 (廟) (meow) (temple)

miào 庙 (廟) (meow) (temple)

nóngmín 农民 (農民) (noong-meen) (farmers)

nóngmín 农民 (農民) (noong-meen) (farmers)

If you’re ever exploring dàzìrán 大自然 (dah-dzuh-rahn) (nature) with a friend who speaks Chinese, a few of these words may come in handy:

àn 岸 (ahn) (shore)

àn 岸 (ahn) (shore)

chítáng 池塘 (chir-tahng) (pond)

chítáng 池塘 (chir-tahng) (pond)

hǎi 海 (hi) (ocean)

hǎi 海 (hi) (ocean)

hǎitān 海滩 (海灘) (hi-tahn) (beach)

hǎitān 海滩 (海灘) (hi-tahn) (beach)

hé 河 (huh) (river)

hé 河 (huh) (river)

hú 湖 (hoo) (lake)

hú 湖 (hoo) (lake)

niǎo 鸟 (鳥) (nyaow) (birds)

niǎo 鸟 (鳥) (nyaow) (birds)

shāmò 沙漠 (shah-maw) (desert)

shāmò 沙漠 (shah-maw) (desert)

shān 山 (shahn) (mountains)

shān 山 (shahn) (mountains)

shāndòng 山洞 (shahn-doong) (cave)

shāndòng 山洞 (shahn-doong) (cave)

shù 树 (樹) (shoo) (trees)

shù 树 (樹) (shoo) (trees)

xiǎo shān 小山 (shyaow-shahn) (hills)

xiǎo shān 小山 (shyaow-shahn) (hills)

yún 云 (雲) (yewn) (clouds)

yún 云 (雲) (yewn) (clouds)

Talkin’ the Talk

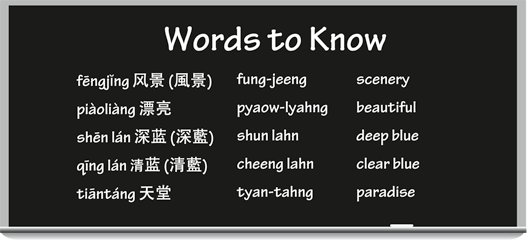

Herman:

Nǐ kàn! Zhèr de fēngjǐng duōme piàoliàng!

nee kahn! jar duh fung-jeeng dwaw-muh pyaow-lyahng!

Look! The scenery here is gorgeous! (Literally: How gorgeous the scenery here is!)

Serena:

Nǐ shuō duìle. Zhēn piàoliàng.

nee shwaw dway-luh. jun pyaow-lyahng.

You’re right. It’s truly beautiful.

Herman:

Shénme dōu yǒu: shān, shēn lán de hǎi, qīng lán de tiān.

shummuh doe yo: shahn, shun lahn duh hi, cheeng lahn duh tyan.

It has everything: mountains, deep blue ocean, and clear sky.

Serena:

Nǐ shuō duìle. Xiàng tiāntáng yíyàng.

nee shwaw dway-luh. shyahng tyan-tahng ee-yahng.

You’re right. It’s like paradise.

xiàng nǐ dìdì yíyàng 像你弟弟一样 (像你弟弟一樣) (shyahng nee dee-dee ee-yahng) (like your younger brother)

xiàng qīngwā yíyàng 像青蛙一样 (像青蛙一樣) (shyahng cheeng-wah ee-yahng) (like a frog)

xiàng fēngzi yíyàng 像疯子一样 (像瘋子一樣) (shyahng fung-dzuh ee-yahng) (like a crazy person)

Tapping into Your Artistic Side

You may pride yourself on having been the biggest jock, but I bet you still get teary-eyed when you see a beautiful painting or listen to Beethoven. It’s okay, just admit it. You’re a regular Renaissance man and you can’t help it. No more apologies.

Okay, now you’re ready to tap into your more sensitive, artistic side in Chinese. Don’t be afraid of expressing your gǎnqíng 感情 (gahn-cheeng) (emotions). The Chinese will appreciate your sensitivity to a shānshuǐ huà 山水画 (山水畫) (shahn-shway hwah) (landscape painting) from the Sòng 宋 (soong) dynasty (960–1279) or to the beauty of a cíqì 瓷器 (tsuh-chee) (porcelain) from the Míng 明 (meeng) dynasty (1368–1644).

I bet you have tons of chuàngzàoxìng 创造性 (創造性) (chwahng-dzaow-sheeng) (creativity). If so, try your hand at one of these fine arts:

diāokè 雕刻 (雕刻) (dyaow-kuh) (sculpting)

diāokè 雕刻 (雕刻) (dyaow-kuh) (sculpting)

huà 画 (畫) (hwah) (painting)

huà 画 (畫) (hwah) (painting)

shūfǎ 书法 (書法) (shoo-fah) (calligraphy)

shūfǎ 书法 (書法) (shoo-fah) (calligraphy)

shuǐcǎi huà 水彩画 (水彩畫) (shway-tsye hwah) (watercolor)

shuǐcǎi huà 水彩画 (水彩畫) (shway-tsye hwah) (watercolor)

sùmiáo huà 素描画 (素描畫) (soo-meow hwah) (drawing)

sùmiáo huà 素描画 (素描畫) (soo-meow hwah) (drawing)

táoqì 陶器 (taow-chee) (pottery)

táoqì 陶器 (taow-chee) (pottery)

Striking Up the Band

Do you play a yuè qì 乐器 (樂器) (yweh chee) (musical instrument)? It’s never too late to learn, you know. Like kids all over the world, lots of Chinese children take xiǎo tíqín 小提琴 (shyaow tee-cheen) (violin) and gāngqín 钢琴 (鋼琴) (gahng-cheen) (piano) classes — often under duress. They appreciate the forced lessons when they get older, though, and have their own kids.

You don’t have to become a professional yīnyuèjiā 音乐家 (音樂家) (een-yweh-jyah) (musician) to enjoy playing an instrument. How about trying your hand (or mouth) at one of these?

chángdí 长笛 (長笛) (chahng-dee) (flute)

chángdí 长笛 (長笛) (chahng-dee) (flute)

chánghào 长号 (長號) (chahng-how) (trombone)

chánghào 长号 (長號) (chahng-how) (trombone)

dà hào 大号 (大號) (dah how) (tuba)

dà hào 大号 (大號) (dah how) (tuba)

dà tíqín 大提琴 (dah tee-cheen) (cello)

dà tíqín 大提琴 (dah tee-cheen) (cello)

dānhuángguǎn 单簧管 (單簧管) (dahn-hwahng-gwan) (clarinet)

dānhuángguǎn 单簧管 (單簧管) (dahn-hwahng-gwan) (clarinet)

gāngqín 钢琴 (鋼琴) (gahng-cheen) (piano)

gāngqín 钢琴 (鋼琴) (gahng-cheen) (piano)

gǔ 鼓 (goo) (drums)

gǔ 鼓 (goo) (drums)

lǎbā 喇叭 (lah-bah) (trumpet)

lǎbā 喇叭 (lah-bah) (trumpet)

liùxiánqín 六弦琴 (lyo-shyan-cheen) (guitar)

liùxiánqín 六弦琴 (lyo-shyan-cheen) (guitar)

nán dīyīn 男低音 (nahn dee-een) (double bass)

nán dīyīn 男低音 (nahn dee-een) (double bass)

sākèsīguǎn 萨克斯管 (薩克斯管) (sah-kuh-suh-gwahn) (saxophone)

sākèsīguǎn 萨克斯管 (薩克斯管) (sah-kuh-suh-gwahn) (saxophone)

shuānghuángguǎn 双簧管 (雙簧管) (shwahng-hwahng-gwan) (oboe)

shuānghuángguǎn 双簧管 (雙簧管) (shwahng-hwahng-gwan) (oboe)

shùqín 竖琴 (豎琴) (shoo-cheen) (harp)

shùqín 竖琴 (豎琴) (shoo-cheen) (harp)

xiǎo tíqín 小提琴 (shyaow tee-cheen) (violin)

xiǎo tíqín 小提琴 (shyaow tee-cheen) (violin)

zhōng tíqín 中提琴 (joong tee-cheen) (viola)

zhōng tíqín 中提琴 (joong tee-cheen) (viola)

Playing on a Team

No matter where you go in the world, you’ll find a national pastime. In America, it’s baseball. In most of Europe, it’s soccer. And in China, it’s ping pong, although since Yao Ming came on the scene, basketball has gotten some attention as well. Here are the Chinese terms for these and many other popular sports:

bàngqiú 棒球 (bahng-chyo) (baseball)

bàngqiú 棒球 (bahng-chyo) (baseball)

bīngqiú 冰球 (beeng-chyo) (hockey)

bīngqiú 冰球 (beeng-chyo) (hockey)

lánqiú 篮球 (籃球) (lahn-chyo) (basketball)

lánqiú 篮球 (籃球) (lahn-chyo) (basketball)

lěiqiú 垒球 (壘球) (lay-chyo) (softball)

lěiqiú 垒球 (壘球) (lay-chyo) (softball)

páiqiú 排球 (pye-chyo) (volleyball)

páiqiú 排球 (pye-chyo) (volleyball)

pīngpāngqiú 乒乓球 (peeng-pahng-chyo) (ping pong)

pīngpāngqiú 乒乓球 (peeng-pahng-chyo) (ping pong)

shǒuqiú 手球 (show-chyo) (handball)

shǒuqiú 手球 (show-chyo) (handball)

tǐcāo 体操 (體操) (tee-tsaow) (gymnastics)

tǐcāo 体操 (體操) (tee-tsaow) (gymnastics)

wǎngqiú 网球 (網球) (wahng-chyo) (tennis)

wǎngqiú 网球 (網球) (wahng-chyo) (tennis)

yīngshì zúqiú 英式足球 (eeng-shir dzoo-chyo) (soccer [Literally: English-style football])

yīngshì zúqiú 英式足球 (eeng-shir dzoo-chyo) (soccer [Literally: English-style football])

yóuyǒng 游泳 (yo-yoong) (swimming)

yóuyǒng 游泳 (yo-yoong) (swimming)

yǔmáoqiú 羽毛球 (yew-maow-chyo) (badminton)

yǔmáoqiú 羽毛球 (yew-maow-chyo) (badminton)

zúqiú 足球 (dzoo-chyo) (football)

zúqiú 足球 (dzoo-chyo) (football)

Some sports, such as gymnastics and swimming, actually involve multiple events. Here are the common components of these two sports:

ān mǎ 鞍马 (鞍馬) (ahn mah) (pommell horse)

ān mǎ 鞍马 (鞍馬) (ahn mah) (pommell horse)

dān gàng 单杠 (單槓) (dahn gahng) (high bar)

dān gàng 单杠 (單槓) (dahn gahng) (high bar)

gāo dī gàng 高低杠 (高低槓) (gaow dee gahng) (uneven bars)

gāo dī gàng 高低杠 (高低槓) (gaow dee gahng) (uneven bars)

shuāng gàng 双杠 (雙槓) (shwahng gahng) (parallel bars)

shuāng gàng 双杠 (雙槓) (shwahng gahng) (parallel bars)

zìyóu tǐcāo 自由体操 (自由體操) (dzuh-yo tee-tsaow) (floor exercise)

zìyóu tǐcāo 自由体操 (自由體操) (dzuh-yo tee-tsaow) (floor exercise)

cè yǒng 侧泳 (側泳) (tsuh yoong) (sidestroke)

cè yǒng 侧泳 (側泳) (tsuh yoong) (sidestroke)

dié yǒng 蝶泳 (dyeh yoong) (butterfly stroke)

dié yǒng 蝶泳 (dyeh yoong) (butterfly stroke)

wā yǒng 蛙泳 (wah yoong) (frog-style or breast stroke)

wā yǒng 蛙泳 (wah yoong) (frog-style or breast stroke)

yǎng yǒng 仰泳 (yahng yoong) (backstroke)

yǎng yǒng 仰泳 (yahng yoong) (backstroke)

zìyóu yǒng 自由泳 (dzuh-yo yoong) (freestyle)

zìyóu yǒng 自由泳 (dzuh-yo yoong) (freestyle)

And if you’re a tiàoshuǐ yùndòngyuán 跳水运动员 (跳水運動員) (tyaow-shway yewn-doong-ywan) (diver), you’d better not pà gāo 怕高 (pah gaow) (be scared of heights).

Remember: Some games require the use of pīngpāngqiú pāi 乒乓球拍 (peeng-pahng-chyo pye) (ping-pong paddles), wǎngqiú pāi 网球拍 (網球拍) (wahng-chyo pye) (tennis rackets), or qiú 球 (chyo) (balls). All games, however, require a sense of gōngpíng jìngzhēng 公平竞争 (公平競爭) (goong-peeng jeeng-jung) (fair play).

Here are some useful phrases to know, whether you’re an amateur or a professional athlete. At one time or another, you’ve certainly heard (or said) them all.

Nǐ shūle. 你输了. (你輸了.) (nee shoo-luh.) (You lost.)

Nǐ shūle. 你输了. (你輸了.) (nee shoo-luh.) (You lost.)

Wǒ dǎ de bútài hǎo. 我打得不太好. (waw dah duh boo-tye how.) (I don’t play very well.)

Wǒ dǎ de bútài hǎo. 我打得不太好. (waw dah duh boo-tye how.) (I don’t play very well.)

Wǒ yíngle. 我赢了. (我贏了.) (waw yeeng-luh.) (I won.)

Wǒ yíngle. 我赢了. (我贏了.) (waw yeeng-luh.) (I won.)

Wǒ zhēn xūyào liànxí. 我真需要练习. (我真需要練習.) (waw jun shyew-yaow lyan-she.) (I really need to practice.)

Wǒ zhēn xūyào liànxí. 我真需要练习. (我真需要練習.) (waw jun shyew-yaow lyan-she.) (I really need to practice.)

If you prefer to spectate from the stands (or from your couch), here’s a list of terms and phrases you need to know if you want to follow the action:

Bǐfēn duōshǎo? 比分多少? (bee-fun dwaw-shaow?) (What’s the score?)

Bǐfēn duōshǎo? 比分多少? (bee-fun dwaw-shaow?) (What’s the score?)

chuī shàozi 吹哨子 (chway shaow-dzuh) (to blow a whistle)

chuī shàozi 吹哨子 (chway shaow-dzuh) (to blow a whistle)

dǎngzhù qiú 挡住球 (擋住球) (dahng-joo chyo) (to block the ball)

dǎngzhù qiú 挡住球 (擋住球) (dahng-joo chyo) (to block the ball)

dé yì fēn 得一分 (duh ee fun) (to score a point)

dé yì fēn 得一分 (duh ee fun) (to score a point)

fā qiú 发球 (發球) (fah chyo) (to serve the ball)

fā qiú 发球 (發球) (fah chyo) (to serve the ball)

Něixiē duì cānjiā bǐsài? 哪些队参加比赛? (哪些隊參加比賽?) (nay-shyeh dway tsahn-jya bee-sye?) (Which teams are playing?)

Něixiē duì cānjiā bǐsài? 哪些队参加比赛? (哪些隊參加比賽?) (nay-shyeh dway tsahn-jya bee-sye?) (Which teams are playing?)

tījìn yì qiú 踢进一球 (踢進一球) (tee-jeen ee chyo) (to make a goal)

tījìn yì qiú 踢进一球 (踢進一球) (tee-jeen ee chyo) (to make a goal)

Wǒ xiǎng qù kàn qiúsài. 我想去看球赛 (我想去看球賽) (waw shyahng chyew kahn chyo-sye.) (I want to see a ballgame.)

Wǒ xiǎng qù kàn qiúsài. 我想去看球赛 (我想去看球賽) (waw shyahng chyew kahn chyo-sye.) (I want to see a ballgame.)

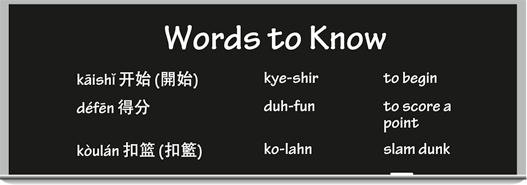

Talkin’ the Talk

Ernest:

Bǐsài shénme shíhòu kāishǐ?

bee-sye shummuh shir-ho kye-shir?

When does the game begin?

Cecilia:

Kuài yào kāishǐ le.

kwye yaow kye-shir luh.

It’s going to start soon.

A few minutes later, the game finally begins.

Ernest:

Wà! Tā méi tóuzhòng!!

wah! tah may toe-joong!

Wow! He missed the shot!

Cecilia:

Méi guānxi. Lìngwài nèige duìyuán gāng gāng kòulán défēn.

may gwahn-she. leeng-why nay-guh dway-ywan gahng gahng ko-lahn duh-fun.

It doesn’t matter. That other player just scored with a slam dunk.

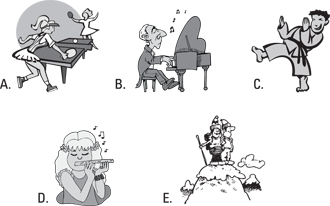

Fun & Games

Fun & Games

What are the people in the pictures doing? Use the correct verb in your response. (See Appendix D for the answers.)

A. ___________________

B. ___________________

C. ___________________

D. ___________________

E. ___________________

A common verb associated with many hobbies is

A common verb associated with many hobbies is  Both

Both