4Death by Dancing in Nijinsky’s Rite

Millicent Hodson

Twenty-five years ago Kenneth Archer and I premiered our reconstruction of the 1913 Rite of Spring with choreography after Vaslav Nijinsky and designs after Nikolai Roerich. Our purpose was to turn the legend of the ballet back into an artifact. We had two goals. The first was to re-create and stage the work, which we have done in more than a dozen countries worldwide. In 2013 Moscow saw the Finnish National Ballet perform the reconstructed Rite at the Bolshoi Festival; the Mariinsky Ballet danced it in Salzburg and Paris, as well as in St. Petersburg; the Theatro Municipal welcomed it back to Rio de Janeiro; and, throughout the United States, it was performed during the centenary year by the Joffrey Ballet, the company with which we first staged the work.

When we premiered our reconstruction in 1987, one hundred versions of the ballet had been created. The figure has doubled since then; some two hundred versions are now known to exist. So our second goal—to inspire other artists and scholars to reconsider The Rite—is continuously fulfilled. (A special hope on my part was for Nijinsky to be regarded concretely as the master of modernism in choreography. He is the Picasso of dance, and I hope my work has revealed why.) The reconstruction is based on a myriad of visual, verbal, and musical clues, including annotations on piano scores by Igor Stravinsky and by Nijinsky’s assistant, Marie Rambert, who also danced in the ballet.1

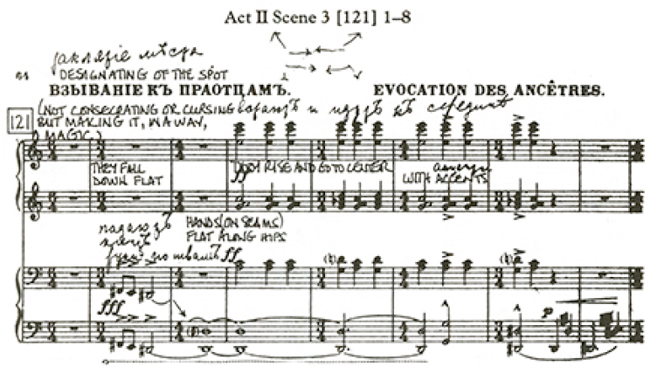

Stravinsky’s annotations about the music in relation to the choreography were written by hand on a piano score apparently during the rehearsal period in 1913. They were published in list form in 1969 as an appendix to The Rite of Spring: Sketches, 1911–1913. The annotations give measure-by-measure details about the dance and music connections, locating each with reference to rehearsal numbers in the orchestral score. These annotations in the Sketches appendix were a key source for the reconstruction, but readers cannot see the annotations in situ on the score because no facsimile with them has been published.

I did not have access to that annotated score until after the premiere of the reconstruction, when Robert Craft gave me a photocopy. Problems with this score were immediately obvious. The handwritten material, some of it in a disordered state, could have been by different hands and entered at different times; any number of writing implements had been used. Who could guarantee the provenance of these markings? But one thing was sure: the material Stravinsky had put into print in the Sketches, often referring to Nijinsky by name, accorded remarkably with Rambert’s own annotations, which she had entered on a printed copy of the piano score in the autumn of 1913, documenting the choreography shortly after the premiere. To my mind the two sets of notes completed each other, and, furthermore, they meshed with the spatial and gestural record that survived in the graphic sketches that Valentine Gross had made during the five Paris performances from 29 May to 13 June 1913.2

The reconstruction is based on this matrix of clues, together with records of the choreography by critics of the time and by the intended soloist, Bronislava Nijinska. I put the clues together like a vast puzzle, letting it make sense gradually, not seeking the larger picture until it revealed itself. My purpose in this essay, however, is not to defend my sources or present proof for the choreography, which I have published widely.3 Instead, I consider the resulting artifact, the reconstructed Rite, and ask what it means.

Individuality and collective action are in constant tension in Nijinsky’s Rite, which is the basis of my threefold argument. First, I suggest that Nijinsky developed a technique of choreographic counterpoint as he created this ballet. Second, I maintain that he achieved something far more complex aesthetically than the Dalcroze Eurhythmics with which he was branded. Finally, I argue that Nijinsky understood intuitively how his technique of counterpoint bridged the poles of individuality and collective action set up by the music score and by the scenario.4 In the course of my argument, I mention the views of a few colleagues whose published statements about Nijinsky’s Rite and my reconstruction contradict the evidence I gathered and the way in which I interpreted it. Two decades after the reconstruction, for example, when Stravinsky’s annotated score had become available for study, Stephanie Jordan attempted to unravel its mysteries, which became the basis for the appendix in the Sketches. Jordan’s intriguing exercise is valuable for scholars of both music and dance.5 However, I find her conclusions debatable, especially her assertion that the annotations had little or nothing to do with Nijinsky’s Rite. Why, then, did Stravinsky keep referring to Nijinsky? And why do Rambert’s notes coincide so closely with Stravinsky’s, only rarely contradicting them? My argument with Jordan, and with an earlier article by Craft,6 is largely about the term “counterpoint.” Nijinsky’s contemporaries used it to describe the new kinds of relationships he created in The Rite, and in this essay I attempt to define what, in my view, those contemporaries perceived. The illustrations and video excerpts that accompany my text reinforce my claims.

Nijinsky and Choreographic Counterpoint

The Rite is a ballet about massed energy, but, as the critics in 1913 documented, it is crammed with particulars as small groups and even single figures pursue their own destinies. Isolation is as fundamental to the choreography as communal effects. Every action of the ballet builds toward the sacrificial solo when, at the end, the Chosen One dances herself to death. For almost half the ballet she is alone in the center of the circle. But her isolation appears as the culmination of the others’ experience: it represents the polarity between their own separateness and the tribe’s cohesion. Isolation manifests itself physically: one part of the body moves while the rest is static, one group dances while all others remain still, and the Chosen One undergoes increasing degrees of separation as her sacrificial solo approaches.

Jean Cocteau and other contemporaries of Nijinsky claimed that Le sacre du printemps prefigured the sacrifice of their generation in what they called the Great War, yet there is no record that Nijinsky associated the war with The Rite. Whether Roerich as scenarist or Stravinsky as composer shared this idea is unknown. Nijinsky, while planning Debussy’s Jeux in London during the summer of 1912, evidently had premonitions about the war, picked up perhaps from pacifist contacts in Bloomsbury.7 Nijinsky’s preoccupation with World War I is apparent not only in his Diary but also in his drawings and his final performance, the St. Moritz solo event he called his “Marriage with God” (1919).

Reminiscent of The Rite, the St. Moritz solo performance closed with an elegy for the men of his generation who died in the trenches, a solo marked by constant falling.8 The sacrificial subject of The Rite may have sensitized Nijinsky to the catastrophe that followed the next year, but the ballet itself made no direct prediction. The sacrifice in this ballet is not an act of physical violence. As shown in Video 4.1, the Chosen One performs her dance untouched until her collapse at the end, after which the Ancestors lift her as an offering to Iarilo, the sun deity. The community is involved throughout, engaged in games and ceremonies that prepare the ground and enable them to identify the one whose death will assure the continuity of life. The scenario and score determined these ritual facts but not how they were to be realized; the ethics of the sacrifice were Nijinsky’s decision, including how the tribe relates to the Chosen One and what her ordeal entails. It is fascinating that Nijinsky, the dancer of legendary leaps, made jumping—indeed, a marathon of jumping—the instrument of the Chosen One’s demise.

The first thing Nijinsky created for The Rite, in November 1912, was this climactic solo. He made it on his sister Bronislava, also an imperial dancer from the Mariinsky, whose body was a differently gendered version of his own: slim in the waist and torso, powerful in the hips and legs—thus perfect for the ordeal of 123 jumps in the “Sacrificial Dance.”9 Early in January 1913 Nijinsky began the ensemble choreography that would change the history of dance. For the groups he multiplied the concepts and movements of the Chosen One, distributing them throughout the half-hour of Stravinsky’s music among the tribe formed from forty-six dancers of Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes. During their early rehearsals the dancers were as shocked by The Rite as the Paris public would prove to be at the premiere. One of them later recalled that the effort was a task requiring the total concentration of each dancer’s mind and body: “The tempo drove us to distraction, with its sharp and unexpected accents. We worked until we, too, were as ready to drop as was Nijinsky, and our heads spun with the interminable repetition of mathematical counts.”10

In his choreography for The Rite Nijinsky explored various analogues of counterpoint. Sometimes, as in the opening measures of the ballet, he made the dancers perform two rhythms on the body simultaneously, the feet dancing one set of accents while the arms perform another, a task requiring total concentration. When the curtain rises, a group of five Young People are hunched over in a partly open circle. At R-13 in the orchestral score they start “bobbing” up and down, as indicated by the Stravinsky and Rambert annotations: the series of  bars are danced as four measures of eight counts (each count is a notated eighth note in the score), accenting the first and fifth beats with a strong stamp. As the Young People continue this rhythm with their feet, they add gestures with their arms timed to Stravinsky’s shifting accents in the subsequent measures, requiring sudden isometric moves on varying locations of a span of eight eighths. Thus, beginning at the third measure of R-13, they move on the second and fourth eighths, on two and five of the next eight eighths, and on one and six of the next eight eighths. This rhythmic shift is tricky enough but truly difficult to do while keeping up the beats of one and five with the feet. To complicate matters further, each man has a different set of gestures, so no one can follow anyone else. The visual effect is an explosion of diversity within the unity of the shared repetitive footwork.

bars are danced as four measures of eight counts (each count is a notated eighth note in the score), accenting the first and fifth beats with a strong stamp. As the Young People continue this rhythm with their feet, they add gestures with their arms timed to Stravinsky’s shifting accents in the subsequent measures, requiring sudden isometric moves on varying locations of a span of eight eighths. Thus, beginning at the third measure of R-13, they move on the second and fourth eighths, on two and five of the next eight eighths, and on one and six of the next eight eighths. This rhythmic shift is tricky enough but truly difficult to do while keeping up the beats of one and five with the feet. To complicate matters further, each man has a different set of gestures, so no one can follow anyone else. The visual effect is an explosion of diversity within the unity of the shared repetitive footwork.

Thus, from the opening of the curtain, Nijinsky’s manifesto is clear: every dancer in The Rite is a soloist, with responsibilities of self-determination, perfection in each individual role, and integration into the whole. In the context of the scenario and score, every member of the tribe goes through the ordeal that is subsumed at the end by the Chosen One. The rigors of counting are one aspect of this ordeal, requiring the kind of concentration that characterizes shamanic ritual—an example of how Nijinsky conflated his revolution in choreography with the underlying idea of the ballet.11

The ordeal of dancing two rhythms on the body simultaneously returns at R-18 when the other men join the fray. In the “Conversation,” as I call this section of the reconstruction, there are a series of gestural exchanges between the Old Woman of 300 Years and the men whom she teaches how to jump and how to divine with twigs (shown in Video 4.2). The men all advance on diagonals to have this gestural conversation with the Old Woman, whose quick shuffles counterpoint their footfalls. The men’s roles in the “Conversation” require total concentration, as they, like the Young Men, must simultaneously perform conflicting rhythms, one for upper-body gestures and one for footwork.12

Nijinsky’s extraordinary gift to choreography was the development of a whole new range of dynamics—visual, kinesthetic, and chromatic. The impact of this discovery derives, I believe, from his intuitive grasp of what these complex formal relations signify within The Rite. To appreciate the way he developed his contrapuntal technique, it is useful to go back now to the beginning of the ballet and observe how he complicates the rhythmic ordeal set up at R-13 and continued at R-18. Throughout R-19 and R-20 the Old Woman makes magical passes with her twigs, marking her own rhythms, as the men respond in a scatter pattern of the preceding accents, like a conversation that gets unruly but never spins out of control. Instead of just “bobbing” in place, however, they now “jump off both feet, moving on,” as Rambert says, “always on the accents.”13 So they close in around the Old Woman, who has called them to center by signaling with her twigs. It is hard enough to organize brain and body while doing this task in place; it is a far greater challenge to make it all happen while moving in space. Applying what Stravinsky and Rambert documented at R-13 and repeated at R-18, I believe the men are meant to follow the composer’s manipulation of the accents, intensifying the ordeal for everyone. No sooner has a performer learned one order than another supplants it. Here is how the pattern looks written down, with the stressed footfalls underlined and the accents for the arms in bold capitals.14 Notice that at the appearance of FIVE and ONE an underlined footfall and bold, capitalized arm accent coincide, but for the most part these contrapuntal movements are offset.

This is the pattern from R-13 that recurs exactly at R-18:

12345678

1TWO3FOUR5678

1TWO34FIVE678

ONE2345SIX78

And this is the complication of the pattern at R-19 through R-20:

12345678

12345SIX7EIGHT

1234

12345678

1TWO34FIVE678

12345678

1234567EIGHT

1TWO3FOUR5678

ONE2345SIX78

A look at these passages on video or in live performance shows the repetitive yet disjunctive effect, the blinkered focus demanded of each dancer, and, at the same time, the collective will all the dancers must exert.

Circles, often circles within circles, are the key configuration in both parts of the ballet. The ensemble counterpoint in Part I is based on the contrast of five separate circles, which establish the main groups and the main energy zones—the center and, roughly, the four corners of the stage. These spatial principles are preserved in the pastels of Valentine Gross. The five circles, one of many shamanic motifs Roerich painted on the costumes, emblazon the red smocks of the Maidens. Because the women’s Part I costumes have fields of solid color as well as vivid motifs, it is not difficult to locate the groups in red, blue, and mauve.15 In Part II, with its somber sacrifice, the groups are not identified by color. Everyone wears smocks with decorative motifs, but all are basically white.

Early in Part I, when the Maidens in Red dance in a block, just after the unwinding circle of their entrance at R-27, they appear almost like banners waving, an analogue of the vitality Stravinsky established in the music for the first part. In each of the five circles on the Maidens’ smocks there is a crossbones motif, a sign of mortality in certain ritual systems and even, in medieval Christian iconography, of resurrection. In The Rite Nijinsky turned the motif into a ground pattern for the moment when the genders engage with each other for the first time, at R-33, as Stravinsky explained in his interview for the journal Montjoie! on the day of the 1913 premiere.16

Jacques Rivière’s November 1913 essay on The Rite refers to “karyokinesis” in the choreography, as in seeds splitting and multiplying in nature, or cell division in the human body.17 Rambert described this sequence at the end of the opening scene to me as “the splitting of the cell,”18 so I used the “Cell” as a rubric for this section of the reconstruction, an example of how choreographic movement is related to costume design. Just before the “Cell,” four groups danced in contrast to each other, working differently with the same musical rhythms at R-31, each group clustered at a corner of the stage. Then suddenly they dance in unison. The motif of the five circles is thus turned into a crossbones figure as the dancers race toward center on separate diagonals, all using the same driving step. They transform the stage picture, shifting the energy from the closure of circles and clusters into open, head-on confrontation. Rarely in my reconstruction of Nijinsky’s Rite do dancers touch, and the adolescent hesitation of the tribes is emphasized here by their sudden halt near the center, which is left empty, followed by the repeated approach and retreat of the groups, always without contact. Rambert’s annotations for these measures and her interview comments refer to this sequence in terms of fertility rites, the groups moving in and out from center in ever-shorter intervals, suggesting a sexual metaphor.

Fundamentally, the shapes of this dance derive from the inverted position used as the foundation of the ballet’s choreography. My research suggests that Nijinsky extended the closed posture to the shape of groups, crouched together in clusters or huddled shoulder to shoulder, and extended it further to the spatial patterns of the choreography: the circles and concentric circles signify nature, and the tight lines and squares represent human construction. Despite the closed postures, groupings, and configurations, there is a sense of expansion outward from the individual to the full ensemble.19 The contrast and multiplication of such shapes is another kind of counterpoint Nijinsky discovered in The Rite, something far more complex than the nascent ideas found in his choreography for Debussy’s Afternoon of a Faun. In Jeux, presented two weeks before The Rite but actually finished after it, Nijinsky tried out some of his contrapuntal techniques on the trio of amorous athletes. After the premiere he recalled in an interview the beauty of tennis movements he had seen at Deauville and how he had the idea of “treating them symphonically.”20 Compared to the shifting masses of The Rite, Nijinsky’s counterpoint on the skeleton crew of Jeux looks quite stark, and for that very reason it underscores the emotional tension of the triangle.

According to accounts of The Rite from 1913, Nijinsky applied his technique of counterpoint not only to the individual body but also to the “body politic” of the ritual community, juxtaposing the rhythm of one group against the rhythm of another. As the Parisian critic Marguerite Casalonga recalled, “The masses execute diversely controlled movements as a group,”21 implying that a variety of rhythmic variations occur within the ensemble movement. The effect is one of diversity within unity.

Rivière, in his seminal essay on The Rite, seized on the paradox: “There is a profound asymmetry in the entire choreography. . . . Each group begins by itself, none of its gestures is dictated by the need to respond, to balance or re-establish an equilibrium. . . . There is no lack of composition here; on the contrary it is there, very subtly, in the encounters, meetings, mixtures and combats of these strange battalions. But this [composition] does take precedence over detail; it does not overrule it; it falls into place within its diversity.”22 The points Rivière makes about asymmetry, complex composition, and unity in diversity are exemplified at the end of the opening scene when the dancing groups, autonomous until now with their different steps and rhythms, suddenly break into the unison movement of the “Cell.”23 Figure 4.1 and Video 4.3 show the final section of the first scene, “Augurs of Spring,” from R-33 through R-36, as groups from the four corners advance and retreat with the same movement in ever-shorter intervals.

Rivière concludes his review by speculating on how the Ballets Russes must have looked to its astonished audience at the Théâtre des Champs-Élysées onstage in 1913: “The impression of unity which we never cease to sense is like that which one feels as he watches the inhabitants of the same sphere circulate, interact, come together and separate, each following its own intentions which are, at the same time, well-known and forgotten.”24 The British dance historian Cyril Beaumont put all this in historical perspective. Listing the benchmarks of the 1913 Rite, he declared that “another innovation, which has been erroneously attributed to the later Massine, was Nijinsky’s attempt to imitate the orchestral pattern in his choreography, so that when a theme was given to a certain instrument, certain dancers would detach themselves from the mass and dance apart, the main body being used as a static or quietly moving background.”25

Figure 4.1. Rome Opera Ballet in the reconstructed Le sacre, Part I, Scene 1, “Augurs of Spring”: the “Cell.” Photograph by Shira Klasmer, 2007. Used with permission.

The corners and center of the stage form the five key zones of movement in Part I, where four groups of dancers frequently form clusters or circles. That means at least one zone is often empty, usually the center. As Part I progresses, the center becomes increasingly important due to its rare, and hence special, use. In the third scene, “Spring Rounds,” at R-48, groups of men and women form lines or circles in the corners as the newly arrived trio of Tall Women in Mauve pass through the central zone, activating it.

Isolation and collective action are organizing principles both for the body of each individual dancer and for the groups in the larger ensemble. During the “Bows” at R-48 the groups move simultaneously but accent different beats of the music: each group has a distinct rhythmic identity but contributes to the larger pattern. The Tall Women in Mauve, making their initial appearance, introduce serenity into the tribal celebrations by detaching from a line of other women and by showing everyone, through their contrapuntal bows, how to honor the earth. Then, in the section I call the “Five-Part Counterpoint” at R-53, the Tall Women in Mauve take the center of the stage. Now there are five groups. Each group had been moving on its own accents, usually at the same point in the score, as if they were all speaking at once in their own way. At this point, however, the groups of dancers begin to alternate. A new level of collective action is achieved, and a sense of hieratic order emerges.

In The Rite of Spring: Sketches, Stravinsky outlines the division of measures for the groups in the “Five-Part Counterpoint,” but he adds that what Nijinsky was doing was “too complex to describe” in words.26 Rambert’s annotations for this same section indicate not only the rhythmic separation and alternation of the groups but also something of their relationships.27 The men tend to be confrontational, facing each other in lines and taking an enormous step toward each other, whereas the women tend to work together in tightly unified circles or triangles. Then the “Five-Part Counterpoint” culminates in a moment of unison far more comprehensive than the “Cell” that ended the first scene. As shown in Video 4.4, the dancers have been variously bowing to the earth, group by group, over and over. At the end of this third scene (not shown in the video clip) they all fall, in slow motion, to the ground. This climax of collective action then dissolves into the Vivo at R-54 and the Tranquillo at R-56, when the five groups reassert their separate identities, all simultaneously following the same melody with disparate movements.

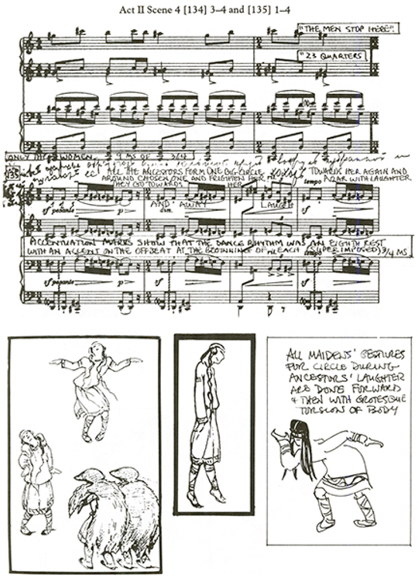

Cyril Beaumont’s analysis of Nijinsky’s Rite went on to explain that “there was also a kind of counterpoint in mass movement, in that now and again one group of dancers danced heavily in opposition to another group which danced lightly.”28 After the opening scenes, during which the five groups of dancers usually address each other—often with their backs to the audience—the women suddenly, toward the end of “Spring Rounds,” charge forward toward the spectators, as in my drawing “Maiden Advancing,” shown in Figure 4.2, a frontal assault of choreography inspired, for me, by Rambert’s annotations and sketches by Gross. The men move laterally, vigorously but less aggressively, spreading out across the stage. Then they all stop abruptly, facing partners in profile, to slap arms, making pacts with each other.29

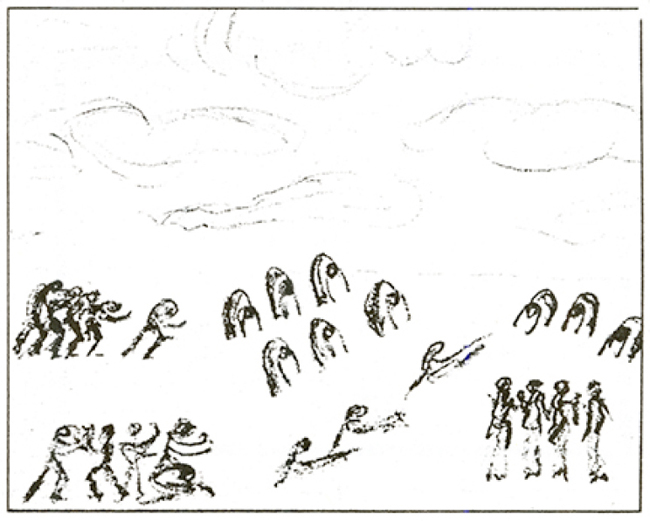

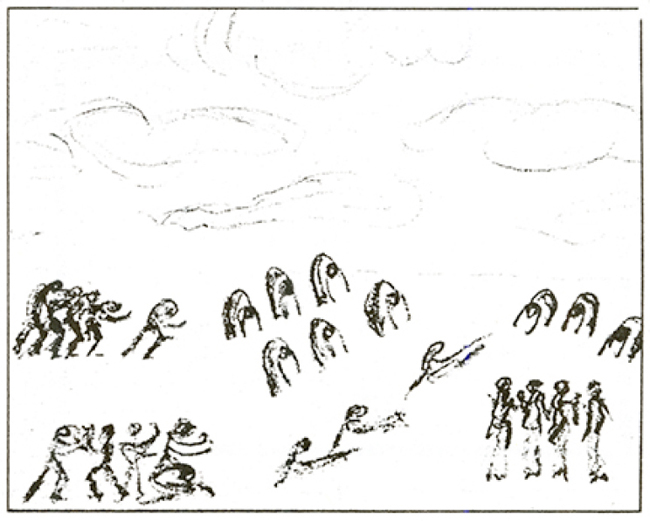

The contrapuntal contrast of force reverses again in the boisterous fourth scene as the men fight with changing opponents and the women flirt to distract them at R-57. Nijinska documented this contrast. When she became pregnant and could not dance, she sometimes attended her brother’s rehearsals, making several drawings of The Rite, among them one from “Ritual of the Rival Tribes,” with men fighting and women flirting, as shown in Figure 4.3. Her distribution of groups shows how much Nijinsky’s use of space had evolved in the year since The Afternoon of a Faun.30 I suggest that his linear design of the groups works a bit like deep-focus footage in film, giving great detail at a distance. The men’s fights in the background are highly diversified, while the women’s responses in the foreground are simplified. These competitive sequences demonstrate the counterpoint of steps with contrasting density that Beaumont noticed, the men thundering and the women skimming the ground in small lateral leaps.

Figure 4.2. Maiden Advancing: “Spring Rounds.” Drawing by Millicent Hodson, 2013.

Figure 4.3. Le sacre Reconstruction Score, Part I, Scene 4, “Ritual of the Rival Tribes” at R-59, “Men’s Fights.” Drawing by Bronislava Nijinska. Published in Millicent Hodson, Nijinsky’s Crime against Grace: Reconstruction Score of the Original Choreography for “Le Sacre du Printemps” (Stuyvesant, NY: Pendragon Press, 1996), 84.

In Video 4.5, an episode in the “Ritual of the Rival Tribes” shows the women distracting the men from their fighting games. Although there are still basically five groups, as at the outset, the circles now give way to linear designs that seem to enlarge the stage and magnify movement. Traditionally, in ritual geometry, circles represent nature or the cosmos, while squares and linear forms represent what is manmade. The lines and blocks of dancers in this scene lead to the tribal squares at the end of the section.

During preparation of The Rite Nijinsky spoke to Rambert about how he wanted to use stasis as a way to help the audience see movement, as Rambert mentioned to me in our 1979 and 1981 interviews and conversations. This idea first appeared with his single leap in The Afternoon of a Faun, a short ballet with a small cast on a shallow stage. Later, in The Rite, he orchestrated almost fifty dancers for half an hour in a vast panorama of motion and stillness.

Nijinsky transferred the concept of counterpoint in music to interactions of movements on the body and interactions of movements among (groups of) bodies in space. With his acute visual sense, he also deployed the vivid primaries of Roerich’s costume groups to maximize the rhythmic contrast of color. When critics in 1913, struggling to describe what they saw onstage, used the word “counterpoint,” they were attempting to capture Nijinsky’s choreographic “orchestration,” involving not just movement but also color and sound. Henry Cope Colles, a critic for the Times of London, recalled:

What is really of chief interest in the dancing is the employment of rhythmical counterpoint in the choral movements. There are many instances, from the curious mouse-like shufflings of the old woman against the rapid steps of the men in the first scene, to the intricate rhythms of the joyful maidens in the last. But the most remarkable of all is to be found at the close of the first [act], where figures in scarlet run wildly around the stage in a great circle, while the shifting masses within are ceaselessly splitting up into tiny groups revolving on eccentric axes.31

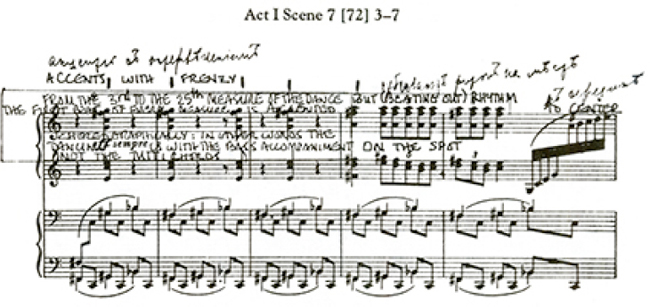

The image preserved by this London critic is visual and spatial, temporal even, but not, per se, musical. He is talking about how Nijinsky used the music to configure different groups of dancers: their relationships to one another in the stage picture more than their relationship to the score. Figure 4.4 shows my staging chart for “Dance of the Earth,” based on the Times article by Colles at the time of the London premiere in 1913 and Rambert’s annotations to The Rite score. The “Simultaneous Solos” at R-72 give way to the “Mandala” and “Spirals” at R-75 through R-77, when the tribes realize they have to organize or the spring energy will be lost.

A month earlier, after the Paris premiere, the French critic Casalonga had reported on the same scene at the end of Part I, the “Dance of the Earth,” mentioning specifically, however, the way Nijinsky’s movement matched the “polyphony” in the orchestra: “The elements are unleashed, the orchestral polyphony breaks forth, and the women dash one after the other in a large circle as if carried along by the wind, while, following the unbridled rhythm, the men surround the old man. It is a universal panic in which clamors of the orchestra accompany this general fury of primitive rhythms through the storm.”32 Note that in Casalonga’s account the dancers are the rhythmic force, which the orchestra accompanies. By contrast, another French critic, Émile Vuillermoz, declares music the motivator and evokes the way Nijinsky’s dancers embodied this sonic power: “You watch the centrifugal force throw terrified women out of the seething mob which is spun around by the lash of the orchestra. . . . This music mows the dancers down in files, passes over their shoulders like a storm over a field of wheat; it throws them in the air, burns their soles. The interpreters of Stravinsky are not simply electrified by these rhythmic discharges; they are electrocuted.”33

Figure 4.4. Staging Chart for the reconstructed Sacre, Part I, Scene 7, “Dance of the Earth”: “Mandala” and “Spirals.” Used with permission of Nauchnyi vestnik Moskovskoi konservatorii.

In the reconstruction, the Maidens in Red run in “ ” meter on the outer rim as, inside the circle, the Young Women in Blue and Tall Women in Mauve run counterclockwise in the notated

” meter on the outer rim as, inside the circle, the Young Women in Blue and Tall Women in Mauve run counterclockwise in the notated  meter, together with six groups of men running in “

meter, together with six groups of men running in “ ,” everything anchored by the Sage in the middle.34 It is a swirling mass of color and motion as the tribes try to organize the chaotic energy unleashed when the Sage kissed the earth at R-71, causing their forty-four simultaneous solos at R-72. The contrapuntal effects are striking at the end of Part I: the Sage enters, stimulating spasms of trembling and then total stillness during his kiss; then he releases the spring, setting off the diversified solos that resolve in what I call the “Mandala” and “Spirals” that finally enclose him.

,” everything anchored by the Sage in the middle.34 It is a swirling mass of color and motion as the tribes try to organize the chaotic energy unleashed when the Sage kissed the earth at R-71, causing their forty-four simultaneous solos at R-72. The contrapuntal effects are striking at the end of Part I: the Sage enters, stimulating spasms of trembling and then total stillness during his kiss; then he releases the spring, setting off the diversified solos that resolve in what I call the “Mandala” and “Spirals” that finally enclose him.

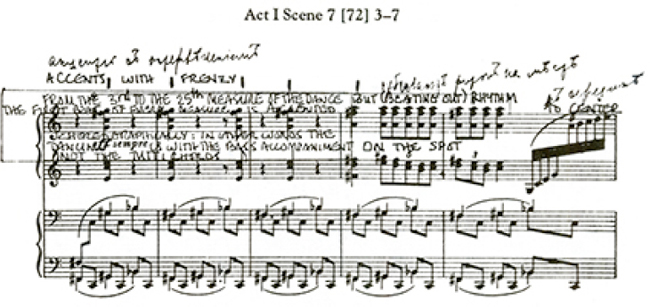

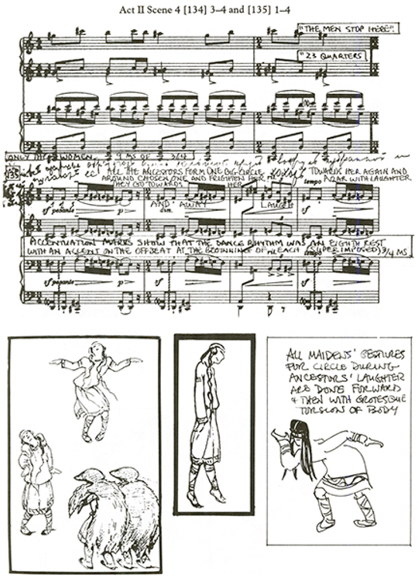

Rambert described this remarkable part of the ballet similarly. Her annotations on the Rite score, shown in Figure 4.5, indicate “accents with frenzy” but “rhythm on the spot” for the “Simultaneous Solos.” The “accents with frenzy” I rendered as a ten-part canon for each group, with frenzied moves taken from clues by 1913 critics, among them Vuillermoz and Casalonga. Stravinsky stated that the rhythm sections, which interrupt the canons, accent the first measure of each bar. Rambert calls it beating out “rhythm on the spot” and then says, “toward the center,” which I interpreted to mean that they all fling their energy toward the Sage, who remains still in the middle of the square.

Figure 4.5. Le sacre Reconstruction Score, Part I, Scene 7, “Dance of the Earth,” R-72:3–7, counts for the “Simultaneous Solos.” Published in Millicent Hodson, Nijinsky’s Crime against Grace: Reconstruction Score of the Original Choreography for “Le Sacre du Printemps” (Stuyvesant, NY: Pendragon Press, 1996), 109. The Rite of Spring by Igor Stravinsky © Copyright 1912, 1921 by Hawkes & Son (London) Ltd. Reprinted by permission of Boosey & Hawkes, Inc.

The solos are organized in canons of ten movements, so that the first person in the group starts on the first movement, the second on the second movement, and so forth, everyone beginning together on count 1 and finishing together on count 10. Two Valentine Gross sketches and clues from contemporary reviews suggested my graphic interpretation for the movement of the solos (see Figure 4.6): jumps, fast turns, and rolls “like bundles of leaves in the wind,” as Stravinsky said he imagined while composing the music for this sequence.35

In the reconstruction, six different groups perform the ten-part canons at R-72. Each of the six groups performs its own sequence of movement in the canon. One group comprises the Five Young People and the Five Young Men; that makes ten people. The first dancer starts on count 1 of the ten-count phrase and finishes on count 10. The second starts on count 2 and finishes on count 1. The third starts on count 3 and finishes on count 2, and so on. Another group comprises the Six Youths. The first starts on count 1, and the second on count 2, but as there are only six dancers, no one starts on counts 7, 8, 9, or 10. The other groups work in the same way.

What makes the canons especially interesting to dance is that the whole ten-count pattern of movement repeats in the second set, yet, crucially, the “accents with frenzy” fall in a different place. The initial canon, for example, has the accent break after count 4. But the repeated canon has the accent break after count 1. This shift undermines the dancers’ physical and mental expectations, as their mastery of the pattern in the first solo set is thus immediately challenged in the second solo set. Without total concentration from all concerned, the image of chaos so carefully constructed can verge into real confusion, destroying the image of diversity moving toward unity.

Figure 4.6. Le sacre Reconstruction Score, Part I, Scene 7, “Dance of the Earth,” R-72:3–7, movements for the “Simultaneous Solos.” Drawings by Millicent Hodson. Published in Millicent Hodson, Nijinsky’s Crime against Grace: Reconstruction Score of the Original Choreography for “Le Sacre du Printemps” (Stuyvesant, NY: Pendragon Press, 1996), 109.

The multiplication of movement in the “Simultaneous Solos” is vast, evoking the vernal profusion that the tribes seek to order through ritual. The “Mandala” brings the groups back to themselves during R-76, which is the second step of organizing the energy, and spring fever is curtailed a bit as everyone inside the circle shifts to the  meter of the Maidens on the outer ring. Then one person from each group starts running to encircle the next, linking the groups in what I call “Spirals,” from R-76:7 through R-77, as the “Mandala” groups become interconnected, the third step of organization. Now they all collectively take responsibility for the energy and deliver it to the Sage, closing in around him from R-78 to make the center ready for the sacrifice. While composing this section, Stravinsky says he imagined the dancers “stomping like Indians trying to put out a prairie fire.”36 Stamping and punching the air, the dancers encircle the Sage, packing closer and closer and consolidating their energy into a single gesture of solidarity.

meter of the Maidens on the outer ring. Then one person from each group starts running to encircle the next, linking the groups in what I call “Spirals,” from R-76:7 through R-77, as the “Mandala” groups become interconnected, the third step of organization. Now they all collectively take responsibility for the energy and deliver it to the Sage, closing in around him from R-78 to make the center ready for the sacrifice. While composing this section, Stravinsky says he imagined the dancers “stomping like Indians trying to put out a prairie fire.”36 Stamping and punching the air, the dancers encircle the Sage, packing closer and closer and consolidating their energy into a single gesture of solidarity.

As such, the “Dance of the Earth,” shown in Video 4.6, is a tour de force, an achievement that definitively broke the mold of nineteenth-century choreography. In the canons, the solos are performed in the large tribal square with the Sage at the center. On stage right are Young Women in Blue, and on stage left are Maidens in Red, both lines perpendicular to the audience. Along the back are Young People and Young Men with the Tall Women in Mauve between them, all these groups heightened by their pointed hats and thus visible as the top line of the square. On the bottom line, across the front, are Youths with hair flying and, in their midst, the three Small Maidens in Red. The Elders form the four corners of the tribal square and a square around the Sage. When the dancers step either forward or backward to make individual space for the solos, four different actions occur, then a rhythm break and the “Fling,” my name for Rambert’s instruction “toward the center,” which is the collective flinging of arms toward the Sage at the center, where the energy accumulates.

First Solo Set:

1 2 3 & 4

Beat 2 3 4 5 Beat 2 3 4 Fling 5 Fling

6 & 7 8 9 10

Second Solo Set:

1

Beat 2 3 Beat 2 3 4 Beat 2 3 4 5 6 Fling Beat 2 3 4 5 6 Fling

2 & 3 4 5 6 & 7 8 9 & 10

Rhythm is the unifying factor throughout The Rite. Toward the end of Part I the stage explodes with individuality, and then suddenly changes into blocks of rhythm, everyone unified by the beat, as the dancers drum on the floor or on themselves. Nijinsky thus added a further dimension of sound to Stravinsky’s score, not just through stamping the earth but through using the body as another percussion instrument. Several maestros who have conducted performances of the reconstruction have commented on the “extra department in the orchestra” constituted by the dancers at such junctures.37 There are other sound effects in the reconstructed Rite that again complement the instruments in the pit, such as the brushing patterns in Part II that arise from the Maidens’ sweeping steps and the foot dragging of the Ancestors.

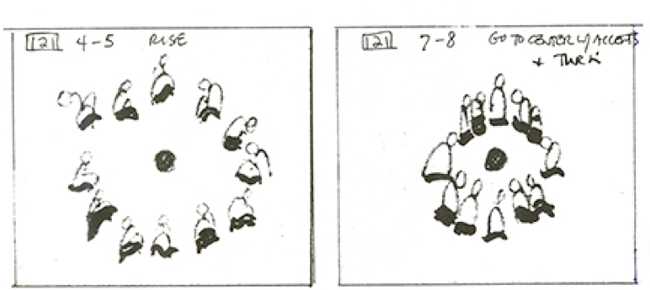

On occasion, especially in Part II, it seems Nijinsky created rhythms for the body that differed from the music; hence, my use of “counterpoint” takes on a more traditional musical sense.38 It is fascinating to see how the counterpoint at the end of Part I reconfigures at the beginning of Part II. The Entr’acte that introduces Part II was not danced in 1913, though it has been included in most versions ever since. Instead, in our reconstruction, the audience contemplates the forthcoming action in Roerich’s painting of an isolated Maiden approached by Ancestors in animal skins. Part I ended with the whole tribe facing the Sage at center; Part II begins with just thirteen Maidens huddled together, facing outward, the center noticeably left empty. The Diaghilev dancer Lydia Sokolova gave the particulars of this opening round.39 Her 1913 memoirs are fresh with details a newcomer had to learn fast, and they are confirmed in drawings by Gross, Emmanuel Barcet, and Serge Soudeikine.

Did Nijinsky come up with the idea of showing how fate chooses the Maiden through her “accidentally” falling onstage? In any case, it is uncannily apt, since falling is what every dancer fears. The annotations by both Stravinsky and Rambert indicate the exact measures in “Mystic Circles of the Maidens” for her first fall at R-101 and the second one that confirms her as the choice at R-102. On Stravinsky’s printed piano score he indicates at R-102 (in Russian and French) that “the dance is interrupted. One of the Maidens is designated by fate to carry out the sacrifice.” And in the Sketches, Appendix 3, he writes that at one measure before R-101 “they stop,” adding “and move again” at R-101. Then at one measure before R-102 he asserts, “And again they stop.” Thus the composer annotates the exact two moments of the fateful selection. Rambert says at one measure before R-101, “The Chosen One falls the first time but rises and continues.” So she specifies falling as the action by one Maiden that has caused the others to stop. Rambert does not write “the second time” for the Chosen One but annotates the extreme reaction of the Maidens after the second stop. At R-102 she explains, “Suddenly troubled they move about on the spot then suddenly, recklessly, throw themselves in a flight around a circle,” clearly reacting to the Chosen One’s second fall. During the explosion that Stravinsky labels “eleven short accents with the music” in the second measure of R-103, Rambert declares that the Maidens “then on the spot stamp furiously and bend their knees,” which launches the militant next scene, “Glorification of the Chosen One.”40

Soon they dance what I have named the “Labyrinth,” from R-93:3 through R-96, which, like the “Mandala,” creates choreographic counterpoint by giving patterns of movement lasting five, three, and two quarter notes, but this time divided among three groups of Maidens (see Video 4.7). Rambert, who was dancing The Rite in 1913 and assisting Nijinsky, documents this scene with a specificity equal to that of Sokolova, and it is fascinating to see how their descriptions interlock with Stravinsky’s, whose annotations make it possible to determine the counterpoint between groups.41

There is also in The Rite the spatial counterpoint of vertical and horizontal movement. Despite the inverted postures, Nijinsky’s ballet still requires classical dancers, as Rambert maintained, or else contemporary dancers with extreme elevation. Everyone spends a lot of time in the air during The Rite. But there is a low center of gravity to all the movement, even the jumps, and there is little high flying. It is repetitive jumping, low but constant. The body is not straight upright in the jumps but still has to rise vertically. The most complex axis of horizontal/vertical action comes in the “Glorification of the Chosen One,” after her selection, when the women jump over and over again to music that repeats with irregular patterns. The body is not straight upright in the jumps but still has to rise—the liftoff is not from the sternum and hip alignment, as in classical ballet, but from the pelvis, sometimes even with feet flat throughout. Other good examples are the male jumping in the “Ritual of Abduction” and the anti-Romantic double duet in that same scene.

In the relentless jumps of the “Glorification,” the women teach the Chosen One the signature phrase that she must mirror in her “Sacrificial Dance” at the end of the ballet. Once the Chosen One is identified, the Maidens work as a tight group, taking her through degrees of separation: glorifying, strengthening, isolating, even doing her initiatory jumps in mirror image to prepare her for the “Sacrificial Dance” (see Figure 4.7).

Figure 4.7. Hyogo Performing Arts Ballet, Kobe, in the reconstructed Sacre, Part II, Scene 2, “Glorification of the Chosen One”: “Mirror Jumps” toward the soloist, Motoko Hirayama. Photograph by Takashi Iijima, 2005, copyright Takashi Iijima / Hyogo Performing Arts Center.

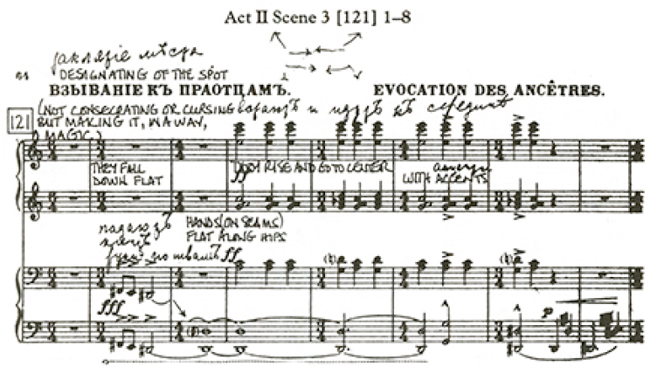

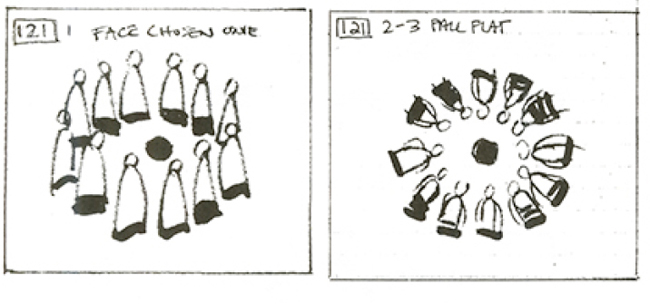

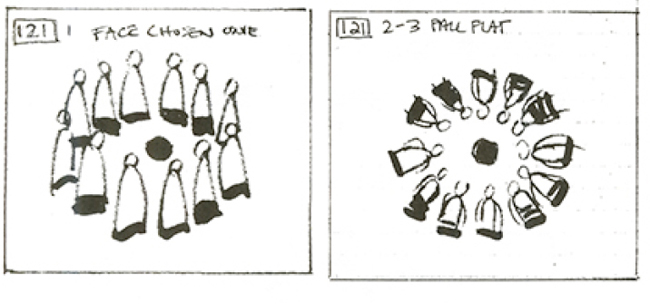

Figure 4.8a–b. Le sacre Reconstruction Score, Part II, Scene 3, “Evocation of the Ancestors” at R-121, the ground pattern of the “Maiden’s Falls.” Drawings by Millicent Hodson. Published in Millicent Hodson, Nijinsky’s Crime against Grace: Reconstruction Score of the Original Choreography for “Le Sacre du Printemps” (Stuyvesant, NY: Pendragon Press, 1996), 148. The Rite of Spring by Igor Stravinsky © Copyright 1912, 1921 by Hawkes & Son (London) Ltd. Reprinted by permission of Boosey & Hawkes, Inc.

Then, in another extreme example of horizontal movement noted by Rambert on her annotated score, the women fall flat on the floor a total of six times in the “Evocation of the Ancestors.” (Figure 4.8a shows the score for this section; Figure 4.8b shows the pattern of falls.)42

Their wild jumps are the key moment of verticality in the ballet until the Chosen One’s solo and are juxtaposed immediately with the key moment of horizontality, the flat falls. In the section of Part II spanning the scenes “Glorification of the Chosen One” and “Evocation of the Ancestors,” the most extreme sequence of jumping in The Rite is juxtaposed against the most extreme sequence of falling. Nijinsky thus created what could be called spatial counterpoint, contrasting vertical and horizontal movement. As shown in Video 4.8, the dynamism of the independent sequences is increased by their proximity, making each more distinct by association with the other.

In the Chosen One’s solo, despite its many jumps, there are an equal number of grounded movements, such as drops, falls, and spins, to contrast with the elevations. Even the Chosen One’s wide leaps span horizontal distance; they do not attempt to conquer gravity but ride it, like a bird with broken wings, the image used for the arm gestures of these leaps. Contrapuntal spatial relationships abound, but this example must suffice.

Rhythmic Formalism, Not Eurhythmics

To make sense of the influences that led to Nijinsky’s discovery of choreographic counterpoint—understood, in this context, as how critics in 1913 perceived the complexity of his Rite—it is important to ask why critics often applied the label of Dalcroze Eurhythmics. Certainly there is a connection. For example, Rambert told Richard Buckle that she only ever made one choreographic suggestion to Nijinsky for The Rite, having proposed that, at a certain point, “he could use several small circles rather than one large one.”43 She may have brought this idea with her from the Dalcroze Institute in Hellerau, where Diaghilev had spotted her and hired her to work with Nijinsky on Stravinsky’s score. After the London premiere, a critic for the Times mentioned that “one of the dances even suggests one of M. Jaques-Dalcroze’s round games.”44 The comparison with Dalcroze derives from the fact that, as Rambert said, Nijinsky duplicated Stravinsky’s rhythmic structure in The Rite. The Russian émigré critic André Levinson, ever the classicist, railed at Nijinsky for replacing “the plastic, psychological and symbolic content of the dance” with the “whole standard pedagogical arsenal” of Eurhythmics. Dalcroze exercises popular at the time of The Rite included walking in one rhythm and moving the arms in another, a far simpler task than Nijinsky’s inventions but related in principle.45 Nijinsky’s “new rhythmic formalism” had no “right to stifle pure movement,” which to Levinson meant the classical ballet of St. Petersburg’s Imperial Theaters. He protested that “throughout the production, wherever the whirling of the savages, possessed by the Spring and intoxicated by the deity, turned into a tedious demonstration of rhythmic gymnastics and wherever shamans and possessed beings started to ‘walk the notes’ and ‘syncopate,’ there you had the origin of the psychological downfall of the whole idea.”46 Yet when Diaghilev revived The Rite with choreography by Léonide Massine in 1920, Levinson changed his view. Nijinsky’s “dancers were tormented by the rhythm,” he recalled, and he declared, in retrospect, that the 1913 ballet had greater power and significance.47

To be fair, Dalcroze did much more than develop a system of teaching music through rhythmic exercises for the body. He recognized the need to reconceive stage space in terms of movement and offered many theories in this direction, some of which he realized in group demonstrations and productions. But his aesthetic was in fact the opposite of Nijinsky’s angular faceting of movement and asymmetrical juxtapositions of the ensemble. Dalcroze did not embark on the kind of complexity realized in The Rite. He championed the aesthetic of continuous movement and harmony, firmly criticizing Nijinsky’s work and never acknowledging any affinity between them.48 French critics were divided in their views about this influence. Vuillermoz, for whom, like Levinson, Eurhythmics meant simply a training method, declared at the end of the Paris season: “In the course of their travels, the followers of Serge de Diaghilev have had the misfortune to come into contact with the excellent Jaques-Dalcroze, and now the rhythmic gymnastics—a purely pedagogical procedure, do not forget—have been added to the dance and have entered a domain from which they are outlawed by definition.”49 Writers at the time often appropriated the label Eurhythmics not only for Nijinsky’s duplication of Stravinsky’s structure but also for the counterpointing of groups. Some disparaged The Rite and the Dalcroze system, while others, such as Octave Maus, praised both:

I cannot help thinking that M. Nijinsky must be accomplished in rhythmic gymnastics and that the influence of the theories which govern them cannot be far from the revolution in choreography he has founded.

Whether it be a coincidence or a repercussion, Le Sacre du Printemps, from all the evidence, takes up the principles espoused by M. Jaques-Dalcroze, and the application of them here is of the greatest interest.50

Yet Nijinsky’s spatial juxtapositions and syncopations created a far more disruptive spectacle than Dalcroze ever envisioned for his revival of Greek choral movement.51

Levinson’s term “rhythmic formalism,” though pejorative when he first used it in 1913, is a term that, with its echoes of the Russian Futurists and Neo-Primitivists in art, better describes Nijinsky’s technique than Eurhythmics. Painters such as Mikhail Larionov and Natalia Goncharova, for example, delved deeply into Slavic folklore and popular arts, seeking to renew indigenous forms through contemporary rhythm, as, so they asserted, Gauguin had done before them. Certain contrapuntal effects that Nijinsky achieved in “Dance of the Earth” paralleled the painterly techniques of Goncharova and others, especially the faceting of objects and surfaces to show time and movement on canvas. Diaghilev gave Nijinsky books on new French and Russian painting, as we know from Nijinska’s Memoirs,52 so the choreographer knew painterly techniques of faceting.

As Nijinska’s Memoirs reveal, Nijinsky found inspiration both in Gauguin and in the archaic Slavic material that Roerich imparted during preparation of The Rite.53 A letter from Stravinsky to Roerich in January 1913 documents the fact that Nijinsky would not start the ensemble choreography until he had the costume drawings and the actual garments in front of him.54 The shamanic motifs painted on the garments seem to have stimulated his awareness of the choreographic possibilities of ritual design.55 By mid-January 1913 Nijinsky had the elements in hand for the visual and chromatic counterpoint he would devise in The Rite. In his own letter to Stravinsky on the eighteenth of that month, he exulted: “I know what Le Sacre du Printemps will be when everything is as we both want it. For some it will open new horizons, huge horizons flooded with different rays of sun. People will see new and different colors and different lines, all different, unexpected and beautiful.”56

Individuality and Collective Action

In a recent essay about the shamanic content of The Rite, Nicoletta Misler opened areas of inquiry that may link with work being done on rhythm in ritual music, on the psychic states it can induce, and on the nature of the dance that results.57 At some point it would be useful for ethnologists and anthropologists to look at The Rite from this ethnographic and parapsychological perspective. Misler’s article may attract them. Meanwhile, there is the fascinating work in progress by musicologist Tatiana Vereshchagina about the extent to which ritual cults active in Russia early in the twentieth century may have influenced The Rite. She investigates structural components of sectarian practices as they were viewed by ethnographers of the time, for example, the adoration of the earth, walking in circles, and divination, all elements crucial to Roerich’s scenario, Stravinsky’s score, and Nijinsky’s choreography.58 The use of trance-inducing techniques by these sects may prompt a new understanding of the use of repetition and complex counterpoint in The Rite by its designer, composer, and choreographer.

Misler’s view of the original collaborators for The Rite is thought-provoking. Most critics in 1913 concurred that the music, dance, and design were intrinsically unified, but, unlike them, Misler thinks that the audience was confronted with “collisions between three different approaches to the primitive world within one and the same ballet.”59 She explains the differences: “Roerich, for example, brought a passion for ethnographic sources which, however, he linked closely with scholarly research and appreciation. Comparatively indifferent to historical and scientific truth, Igor Stravinsky contributed and conveyed a vaguer, but more modern ‘inner resonance’ of the primitive world, while Vaslav Nijinsky offered the ‘ecstatic’ and physiological identification of the artist with the ‘animal’ reality of the primitive as his own reality.”60

I differ with her view of Nijinsky insofar as I think the choreographer went far beyond what she mentions, integrating Roerich’s vision of the archaic world and the impersonal, “biological” force (as Rivière called it at the time) of Stravinsky’s music. It seems to me that Nijinsky trumped both his collaborators. The great paradox of staging the ballet is that it is a massive corps project but utterly individualized. No two roles are the same, yet the individual parts coincide with group effects so that, like a flock of birds on the wing, deviations give texture but do not disrupt the general pattern. A great deal goes on all at once, but there is none of the improvisation that Fokine introduced. Nijinsky’s effects are sculpted and set to the last detail. That makes an unusual amount of work not only for the dancers but also for the ballet masters whom we train during the rehearsal process and for Archer and me as we stage the work.61

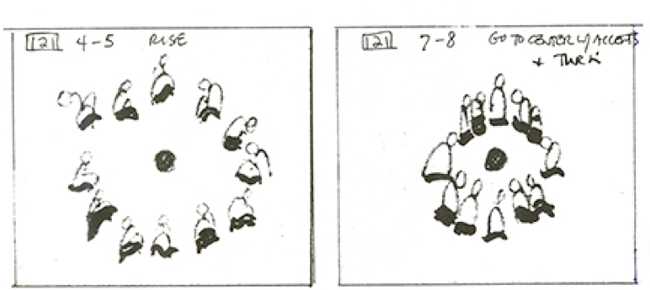

Nijinsky played with the paradox of individuality and collective action from beginning to end of his ballet, highlighting the conflict between consensual necessity—the need to carry out ritual tasks—and personal response. Just as Roerich thought that the Stone Age evinced a sophisticated sense of design, Nijinsky allowed for more emotion than the primal fear that Rivière, Levinson, and their peers reported. An interesting example is the women’s circle of lament in Part II, during the “Ritual Action of the Ancestors.” Figure 4.9a shows how Rambert suggested the contrasting movement of the women and men on her piano score. Figure 4.9b shows the 1913 drawings by Emmanuel Barcet, including gestures of lament the Maidens make as the men perform the “repelling” dance of the Ancestors, ritualized laughter with flat, rigid hands. This image of pathos derives from Nijinsky’s solo as a puppet in Petrushka, which he adapted here for isolation through ridicule, a classic distancing device in victimization. The Maidens’ knife palm in front of their torsos suggests the Chosen One will never live to bear children. The broken line of their open arms is an offering to the sun god, but the bent elbows reveal their sense of loss.

Presumably quoting Nijinsky, Rambert records this sequence as “the repellent dance of the Ancestors, as they close in on the Chosen One, laughing with their hands, as though to disown her.”62 In Video 4.9, the Maidens lament as they circle on the outside, while a ring of Ancestors advances on the Chosen One, isolating her through laughter with their arms—large, syncopated swings and claps. Despite the emotive distinction between the actions of men and women at this point, the men’s aggression is subtly undercut as they drag their feet on the ground, a kind of earth mantra.

The laughing and lamenting sequence presents a kind of emotional counterpoint that sets up the conflict of the Chosen One’s dance, when, as documented by Nijinska, Rambert, and Valentine Gross, the young woman struggles, not simply acceding to her fate.63 This documentation contradicts the reading of Rivière’s essay by many scholars, among them Richard Taruskin and Modris Eksteins, the latter, in his book Rites of Spring: The Great War and Birth of the Modern Age, claiming that Nijinsky’s “Chosen One joined in the Rite automatically,” neither comprehending nor interpreting it.64 Their views are based, I think, on a misreading of Rivière, who, although he preserved through his words many stylistic and compositional traits of Nijinsky’s Rite (an incomparable gift to history), has perhaps skewed perception of what the ballet’s sacrifice signifies. Two statements by Rivière are key: one he defines as “sociological” and the other as “biological.” He declares that “not for one instant during her dance does the Chosen Maiden betray the personal terror which must fill her soul,” and he concludes: “She accomplishes a rite, she is absorbed into a function of the society, and without giving one sign of comprehension or interpretation, she reacts to the powers and the shaking of a being more vast than she.”65

Figure 4.9a–b. Le sacre Reconstruction Score, Part II, Scene 4, “Ritual Action of the Ancestors” at R-134:3, the “Laughing and Lamenting Circles.” In Figure 4.9b the Maidens’ knife palm gesture (figure at left in the Barcet drawing on the left), their offering gesture (figure at the top of the Barcet drawing on the left), and the figure in the Barcet drawing at center all capture the sense of lament. The Hodson drawing at right, with its extreme twist, conveys the depth of the Maidens’ anguish for their peer. Drawings by Emmanuel Barcet and Millicent Hodson. Published in Millicent Hodson, Nijinsky’s Crime against Grace: Reconstruction Score of the Original Choreography for “Le Sacre du Printemps” (Stuyvesant, NY: Pendragon Press, 1996), 160. The Rite of Spring by Igor Stravinsky © Copyright 1912, 1921 by Hawkes & Son (London) Ltd. Reprinted by permission of Boosey & Hawkes, Inc.

Yet numerous critics marveled at the dramatic projection of the soloist, among them the composer Florent Schmitt, who affirmed that “Mlle Piltz . . . performs the ‘Danse Sacrale’ with a painful and tragic passion.”66 It seems to me that Nijinsky’s choreography required a different kind of projection from the dancers than was standard in classical dance and even in the popularized classicism of the Ballets Russes. Rivière himself observed how, in Nijinsky’s Rite, “the face no longer plays an independent role, it is an extension of the body, its blossom.”67 Rambert made exactly that point to me in our interviews: the face is a mask, the body tells everything. What this means is that the imperial tradition of ballet acting, with the histrionic raptures and grimaces that Fokine’s innovations only exaggerated, was now abolished. Perhaps Nijinsky painted each dancer’s face with ritual signs as a reminder, by means of the stylized makeup, not to move those muscles and to remember, as Rivière claims, that “the body is the real speaker.”68 At the same time that Nijinsky abolished facial expression, he reduced the dancers’ presentational relationship to the audience. Paris was offended by the fact that the cast of The Rite turned their backs on the public and faced each other in circles and squares. Choreography was suddenly about carrying out a collective ritual task instead of showing off for the spectators and telling them a story.

How, then, do these bodies function in what Rivière ultimately concludes is a “biological ballet”? He says Nijinsky provided “a piece of the primitive globe which has been conserved without aging and which continues to breathe mysteriously before our eyes,” a ballet that is impersonal, evolutionist, even mechanistic.69 He evokes blindness and thinks of animals circling in a cage, images of power constrained. But he also says, in so many words, that Nijinsky returns the dancer to a unified whole that predates the Cartesian mind/body split: “There is an enormous question borne about by all these beings that move under our eyes. And it is no different than themselves. . . . They have no organ other than their entire organism and it is with this that they search.”70 Such was the program of new dance that Nijinsky initiated: choreography that returned to the body’s “most etymological inclinations,” as Rivière put it, that declared freedom through formal reduction and sought communication through simpler means.71 Before long Nijinsky’s Rite had its progeny in the Ausdruckstanz of Central Europe and what became known as modern dance in America. The discoveries of The Rite took root, as Rivière predicted, when he mused that “it is exactly the characteristic of masterpieces to create for their use an expression which is so complete, so useful and so new that it quite naturally becomes a general technique. . . . True fecundity is born of extreme urgency. Stravinsky and Nijinsky, because they wanted only to resolve a particular problem, have in fact discovered a general solution.”72

Among those present at the creation, Rivière understood better than most what he had witnessed. But even if he was willing to forgo dramatic projection and direct address to the audience on the part of the dancers, he missed in The Rite what we might call “affect” and “catharsis,” what he himself calls “a moral quality” that “always partakes of pity.” He reflected: “There are works which overflow with despair, with hopes, with encouragements. One finds in them reason to suffer, to regret, to take heart; they contain all the beautiful agitations of the soul; one gives oneself up to them just as one listens to the advice of a friend; they have a moral quality and always partake of pity.”73

Instead, The Rite leaves him with the “panic terror which accompanies the rising of the sap,” as he quotes from Stravinsky.74 But does that mean the Chosen One, however archaic, was not a human being? The critics, including Rivière, had theatrical habits that were hard to break. Does their response prove that Nijinsky meant the soloist to be unthinking, unaware, and totally passive in her fear? The documents on which the reconstruction is based do not, in my opinion, justify that characterization. Nijinska, Rambert, and Gross all show the Chosen One making a break for freedom before, in the end, she accepts the heroic role of saving her tribe by destroying herself. Rambert’s annotations mark the places in the music where the Chosen One “runs across” to the edge of the chalk circles that entrap her. Then Nijinska explains that she stamps her feet like a bird building a nest. She tries again to escape, according to Rambert, and then, as Nijinska reports, she beats her wings as though attempting to fly away from the chalk enclosure.

Taruskin and I have argued whether or not the sacrificial dancer evokes sympathy, the so-called pathetic fallacy, publicly and privately, a debate summarized in the New York Times and the New Yorker after the “Reassessing The Rite” conference in 2012.75

Early in my research I went to what was then Leningrad to meet with Vera Krasovskaya, who had published Nijinska’s notes on the solo in Russian. I needed to know if Krasovskaya had any other material that she had yet to publish, and she did not. But she told me how she had taken Nijinska’s transcript of the “Sacrificial Dance” to the aging Maria Piltz, the original 1913 Chosen One, who was then in a home for former artists of the Imperial Theaters. Krasovskaya had asked Piltz to question and confirm each movement. Rambert watched some of the rehearsals during which Nijinsky taught the role to Piltz and declared in her autobiography that when Nijinsky did the role in the studio, it was the “most tragic dance” she had ever seen.76 Nijinsky himself returned to the image of the artistic sacrifice in his St. Moritz drawings.77 In the reconstruction, the Ancestors at the end of the Chosen One’s solo swoop her up off the ground, another fragment of shamanic ritual to which Stravinsky refers in his Montjoie! interview. She is offered to the sun god as his bride in order, as Nijinska quoted her brother in rehearsal, “to save the earth,” a comment taken to heart by dancers of the reconstructions worldwide. Most of them are committed ecologists, and they take the ideas of the original Rite into the twenty-first century with a new passion.

In 1913 Piltz came through the ordeal of the solo, despite the audience’s noisy confrontations, with unanimous praise, a process the Royal Ballet’s Zenaida Yanowsky powerfully enacted nine decades later in the BBC film Riot at the Rite.78 As any Chosen One will confirm, it is enough to dance this marathon solo, let alone cope with a riotous audience. The dancer experiences an emotional arc of great intensity, and her attempts to escape from the chalk circles, so clearly indicated in the sources, heighten the effect of her struggle. Her movement (see Video 4.10) is almost always in counterpoint to the Ancestors in their Procession around her, the climax, at length, of the exacerbated tension between individual and collective forces.

In the end the soloist has to carry the performance. It is a lonely task, but not without support (see Figure 4.10). The tribe in the ballet are her peers in real life, and in contrast to the company dynamics portrayed in films such as Darren Aronofsky’s Black Swan (2010), the community of dancers, along with the conductor in the pit, are lending her energy, even though the stabbing jumps and thrashing baton might seem, dramatically, to be driving her into the ground. As Archer and I continue to stage what he terms our “reasonable facsimile” of the 1913 Rite, we find that dancers everywhere identify with the Chosen One as an image of Nijinsky’s dedication to his art. I consider this solo his true autobiography.

Figure 4.10. Igor Dronov, conductor at the Bolshoi Theatre, and Mira Ollila, Chosen One for the Finnish National Ballet premiere of the reconstruction as part of the 2013 Sacre Festival in Moscow. Still from De utvalda [The chosen ones], a film by Anna Blom, Ville Tanttu, and Ditte Uljas, YieFilm and Ja! Media, Helsinki and Moscow, 2013–14. Performances are shown by permission of the Finnish National Ballet, director, Kenneth Greve; the Bolshoi Orchestra, conductor, Igor Dronov; Mira Ollila; and the reconstructors of the 1913 Le sacre, Kenneth Archer and Millicent Hodson.

When staging The Rite, I ask each Chosen One to find for herself the moment, in this consummate piece of theater, at which she accepts her fate. The impact of that moment comes from what I sense to be Nijinsky’s recognition, somehow embedded in the movement of the dance, that the Chosen One’s fate was his own. The self-inflicted exhaustion of the solo is an allegory of every dancer’s dedication, not least Nijinsky’s.

Notes

bars are danced as four measures of eight counts (each count is a notated eighth note in the score), accenting the first and fifth beats with a strong stamp. As the Young People continue this rhythm with their feet, they add gestures with their arms timed to Stravinsky’s shifting accents in the subsequent measures, requiring sudden isometric moves on varying locations of a span of eight eighths. Thus, beginning at the third measure of R-13, they move on the second and fourth eighths, on two and five of the next eight eighths, and on one and six of the next eight eighths. This rhythmic shift is tricky enough but truly difficult to do while keeping up the beats of one and five with the feet. To complicate matters further, each man has a different set of gestures, so no one can follow anyone else. The visual effect is an explosion of diversity within the unity of the shared repetitive footwork.

bars are danced as four measures of eight counts (each count is a notated eighth note in the score), accenting the first and fifth beats with a strong stamp. As the Young People continue this rhythm with their feet, they add gestures with their arms timed to Stravinsky’s shifting accents in the subsequent measures, requiring sudden isometric moves on varying locations of a span of eight eighths. Thus, beginning at the third measure of R-13, they move on the second and fourth eighths, on two and five of the next eight eighths, and on one and six of the next eight eighths. This rhythmic shift is tricky enough but truly difficult to do while keeping up the beats of one and five with the feet. To complicate matters further, each man has a different set of gestures, so no one can follow anyone else. The visual effect is an explosion of diversity within the unity of the shared repetitive footwork.

” meter on the outer rim as, inside the circle, the Young Women in Blue and Tall Women in Mauve run counterclockwise in the notated

” meter on the outer rim as, inside the circle, the Young Women in Blue and Tall Women in Mauve run counterclockwise in the notated  meter, together with six groups of men running in “

meter, together with six groups of men running in “

] but the rhythms of the other groups are too complex to describe, and I will confine myself to one example” (Stravinsky, The Rite of Spring: Sketches, app. 3, 38).

] but the rhythms of the other groups are too complex to describe, and I will confine myself to one example” (Stravinsky, The Rite of Spring: Sketches, app. 3, 38). , until, with the change to the “Spirals” in the sixth measure of R-76, I pulled everyone into the

, until, with the change to the “Spirals” in the sixth measure of R-76, I pulled everyone into the