It has become a commonplace to read Igor Stravinsky’s and Vaslav Nijinsky’s ballet Le sacre du printemps as a work defined by its Russianness, whether in terms of its staging and choreography or with respect to its music. Yet for all the painstaking detective work that traces its Russian sources and for all the unspoken essentialism this entails, this mythologizing interpretation of the work often ignores the local context of the work’s genesis and reception. By relocating Le sacre du printemps in 1913 Paris, I propose a view of the ballet as a French production steeped in local specificity. Drawing on recent theories of cultural mobility and translation studies, I read Le sacre as a quintessentially Parisian artifact tailored to an elite audience that valued the exotic as a marker of cosmopolitan nationalism. Seen in this light, the scandal of the premiere had less to do with “shocking” sights and sounds than with mixed messages and missing signposts.

The momentous misalignment between the creators of the production and their target audience became apparent when, in April and May 1913, and as was usual in the lead-up to a major cultural event in the French capital, newspapers started to prepare Parisian audiences for the next in a series of spectacular premieres: that of Le sacre du printemps. The morning before its opening night, on 29 May, a widely published press release indicated that it was to be “the most surprising realization ever undertaken by the admirable company of Monsieur Serge de Diaghilev.” “Powerfully stylized,” it would reveal the “characteristic attitudes of the Slavic race as it gains consciousness of beauty in prehistoric times.” Audiences were also promised a “new thrill” that would leave an “unforgettable impression.”1 Such a compelling advertisement was certainly needed for a new production in danger of going under in the context of what had appeared to be a somewhat lackluster season for the Ballets Russes, not least because Claude Debussy’s new ballet, Jeux, had failed to spark any excitement. After the sensational visits that had brought Les sylphides (1909), Schéhérazade (1910), L’oiseau de feu (1910), and Petrushka (1911) to Paris, even the Ballets Russes needed to make a new work stand out to succeed in the Parisian marketplace.2

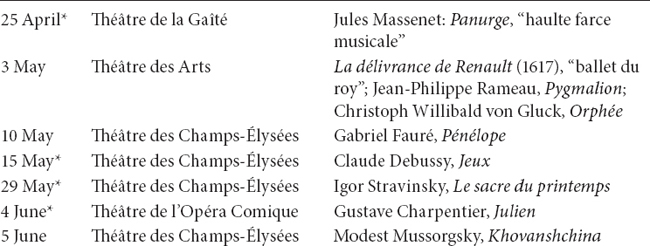

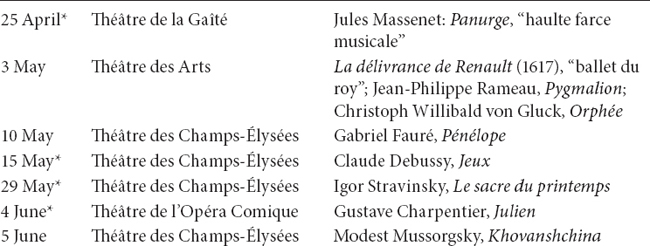

Table 5.1. Significant premieres at Parisian theaters in April and May 1913. World premieres are indicated by an asterisk.

Indeed, Le sacre had to compete with a number of major premieres in Paris in the space of fewer than six weeks (see Table 5.1). The posthumous premiere of Jules Massenet’s “haulte farce musicale” (grand musical farce), Panurge, on 25 April at the Théâtre de la Gaîté was followed by the successful first Parisian performance of Gabriel Fauré’s only opera, Pénélope, on 10 May at the Théâtre des Champs-Élysées. Then 4 June saw the premiere of Gustave Charpentier’s Julien, the eagerly awaited sequel to his hit opera Louise, which took place at the Théâtre de l’Opéra Comique. On the next day, 5 June, Modest Mussorgsky’s little-known opera Khovanshchina received its Parisian premiere in a version adapted by Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov, Maurice Ravel, and Igor Stravinsky.3 In between those major events, other, smaller ones vied for public attention, whether the premiere of Debussy’s ill-fated ballet Jeux on 15 May, or, on 3 May, the production at the Théâtre des Arts of a spectacle that included the first modern performance of La délivrance de Renault, a 1617 “ballet du roy” from the court of Louis XIII (alongside Rameau’s Pygmalion and act 1 of Gluck’s Orphée). These were only the premieres taking place on the main stages of Paris. Together with the Parisian reception of the Ballets Russes over the previous years and the broader context of musico-theatrical life in the French capital, these events shaped the cultural field for which Le sacre was created and within which it was received.

The press release about a new prehistoric ballet by Stravinsky, Nijinsky, and Roerich points to this Parisian context through a number of revealing formulations, locating Le sacre at a rather unusual place between boulevard sensationalism, musical ethnography, cultural mediation, and modernist art. Yet for the readers of Parisian newspapers, the press release sent mixed messages about what they were going to see and hear that evening. Whereas the reference to the “most stunning polyrhythms which ever emerged from a musician’s brain” pointed to Stravinsky’s celebrated musical genius, the “evocation of the primal gestures of pagan Russia” suggested the balletic representation of a vaguely Orientalist Russia associated with the pre-Christian East. The reference to “the Slavic race” gaining “consciousness of beauty in prehistoric times” is another pointer toward such mediated exoticism, whereas the “new thrill” that would leave an “unforgettable impression” evokes more sensationalist entertainment. How that would correlate, however, with the “prodigious Russian dancers” expressing the “stammerings of a half-savage humanity” was anyone’s guess.4

On the basis of this announcement, Parisians would have expected at least some kind of titillating spectacle tailored to their taste for exotic extravaganzas. In a somewhat twisted fashion, that is just what Diaghilev offered in his new ballet. Indeed, as Joan Acocella has speculated rather convincingly, Le sacre might well have been the work in which the impresario acceded in the most deliberate fashion to the expectations of his Parisian audiences, namely, that the Russian troupe was at its best when offering splendidly barbaric spectacles and a “picturesque de bazar.”5 Yet the alterity that Diaghilev and his collaborators presented in the new production did not entirely fit the accustomed manner of Parisian exoticism and also turned out to be wholly incongruous with its performance context in as elegant a Parisian theater as the Théâtre des Champs-Élysées. As the audience flocked to the first night of the ballet, it was clear that they would be attending an event of great significance, as befitted a major Parisian premiere, and that they would serve as the initial arbiters of taste. But the first hints that Le sacre might not be quite in the same vein as earlier Russian ballets came on the heels of the dress rehearsal on 28 May, to which select critics and insiders had been invited.6 The first-night audience, too, was not offered what it had been led, or thought it had been led, to expect.

Le sacre du printemps was, I contend, a ballet designed specifically for the French capital, although modern scholars have not always realized this point, treating the city as incidental to, if not obstructive of, the work’s creation and reception. Yet the ballet related to a range of Parisian cultural practices: its subject situated it within a long history of French ballets, pantomimes, and operas; the modernist music spoke to Parisian sensibilities that prided themselves as defining the avant-garde of contemporary art; the presentation of an “authentic” Russian set meshed with performance traditions on Parisian stages, especially the Opéra, since the mid-nineteenth century; the absorption of the exotic and primitive had been a vital part of French cosmopolitan nationalism, in particular after 1870; and foreign artists in Paris had added to the luster of the capital since the Middle Ages. Even the tumultuous audience response during the first four performances of Le sacre corresponded to Parisian reception models developed over the course of about a century that allowed “fighting in the theater” to be “one of several possible responses expressing extreme divergence of taste.”7 Even though, by Parisian standards, the riot at The Rite was one of the milder affairs, receiving less coverage in the daily press than had others, the scandal marked the work as worthy of active audience engagement. Some of Stravinsky’s supporters, such as Ravel, for example, had hoped for at least as much—if not more—of a response so that the ballet’s first performance would be “an event as momentous as the premiere of Pelléas.”8

The scandal, or some anticipation of one, was but one mode through which the performance of Le sacre was marked by its Parisian context of creation. The French capital had a significant impact on other aspects of the work, too. For example, these intersections between the local framework and the artistic agency of foreigners offer a window of interpretation that reveals Le sacre, if not as a French ballet as it would have been written for the Opéra, then certainly as one that embodied Parisian aesthetics and cultural practices.9 I wish here to consider three particular points of intersection between Le sacre and its performance environment: the ballet’s topic and its staging, the discourse about the music’s character, and the issue of the foreign national identity of its creators. I do so in order to redirect some of the discussion about the ballet away from what scholars such as Richard Taruskin have interpreted as the creators’ Russianist intentions and toward a context-oriented interpretation of the event.10 Informed by both ethnomusicological approaches and theories of cultural mobility, I approach the spectacle and the music of this Parisian premiere (as one might any other) from the perspective of a sympathetic observer.

While ritualized pagan virgin sacrifices from prehistoric Russia were certainly not standard fare on Parisian stages, the elements on which the ballet’s creators drew for its plot had a long-standing local tradition. Pagans, virgins, and ritual dances were abundant in French theaters, ranging from such chestnuts as Giacomo Meyerbeer’s Robert le diable (1831), with its infamous dancing nuns, to more modern ballets such as Alfred Bruneau’s 1912 Les bacchantes.11 The latter also exemplified one important strand of pre-Christian topics: after all, the Parisian revivals of Gluck and the related craze for Greco-exotic dances had already left their mark on the Ballets Russes with Nijinsky’s L’après-midi d’un faune from that same year. Whether in Gluck’s Alceste and his two Iphigénies or in Isadora Duncan’s related dance spectacles, ritualized female sacrifice—sometimes of virgins—was par for the course.12 Besides such Greco-exotic spectacles, the Paris opera houses routinely staged works wherein sacrificial female death (if sometimes narrowly avoided by a twist of the plot) served as the culmination. If Gaspare Spontini’s La vestale (1807) was but a faded memory a century later, the gruesome endings of Camille Erlanger’s Aphrodite (1906) and Florent Schmitt’s La tragédie de Salomé (1907) provided a far more immediate local context. The latter culminated in Salome’s “Danse de l’effroi”—premiered by Loïe Fuller—at the end of which “everything descends upon the dancer as she is killed by an infernal delirium.”13 Schmitt was one of Stravinsky’s oldest Parisian friends, and he dedicated the 1911 concert version of the work to his Russian colleague.

If sacrificed women had populated the French stage in various guises, those who danced themselves to death in sacrificial rites were less apparent. This scarcity makes sense, of course, for death by dance could also be seen as a negation of dance itself, whereas using dance to kill, as in one of the best-known Romantic ballets, Giselle, invests the dancers with power over life and death. In Giselle it is not the virgins who dance themselves to death in a nightly ritual; rather, the Wilis make it their business to dance their male victims to their bitter end. Ballets such as La source (1866) do feature danced virgin sacrifices, but although such sacrificial deaths are performed, it is not the dance per se that kills the women. However, as in Le sacre, a number of those “feminine endings” in Parisian ballets and opera relate the women’s demise to nature and to the restoration of the natural order: a flower brings the death of Naïla in La source; a magic branch from a sacred tree leads to the demise of Yedda in the eponymous 1879 ballet by Philippe Gille.14 Another, more cosmopolitan success on the Parisian stage at that time—Richard Wagner’s Götterdämmerung—ends with the heroine’s self-immolation in a funeral pyre that brings about the rejuvenation of nature.15 Yet pagan rites are commonplace in exotic spectacles, whether staged as orgy, sacrificial ceremony, or both. In nineteenth-century opera, as in ballet, such scenes usually involved the corps de ballet engaged in carefully choreographed orgiastic scenes, their disciplined lasciviousness as stylized as any other patterned grouping in classical ballet.

What many of these ballets have in common is the spectacle of dancers appearing in colorful costumes, miming as much as dancing. These balletic presentations were not limited to the main stages of Paris; rather, they often happened in alternative venues. Ballet-pantomime, for example, had found a place in music halls and the boulevard theater, thus shifting our focus to performance spaces other than the Opéra and Opéra Comique.16 At the Casino de Paris, for example, the plot of Fumées d’opium (1909) served as a scant pretext for an opium-generated dream orgy, including the near sacrifice of a virgin to Venus, while in Nitokris, a “légende égyptienne” presented at the Olympia in 1911, the heroine is punished by sacrificial death in an ancient Egyptian temple. The ballet ends with a “danse de folie” (mad dance) after her demise.17

If female sacrifice and pagan rite were in the mainstream of Parisian theatrical topics, what distinguished Le sacre was its location in prehistoric Russia—as opposed to the more standard pagan Greece or Orient—and its greater accumulation of exoticizing tropes. Yet the performance of ancient and prehistoric rites also had a history in Paris, not least when showcased prominently at the Expositions Universelles of 1889 and 1900 and in the various so-called human zoos at the Jardin d’Acclimatation, where peoples from abroad (many from Africa, Indochina, and Micronesia) were exhibited with props from their home environments.18 From a Parisian perspective, the cultures of these ethnic groups were cast, predictably, as unrefined early stages of human progress; the interest they aroused lay in their embodied differences not only in terms of ethnicity but also with respect to the timelessness ascribed to their cultures.19 In May and June 1913, during the time when Le sacre du printemps was being performed, a group of about sixty Circassians from the Caucasus were camped out on the Great Lawn of the Jardin d’Acclimatation.20 People flocked there to experience their songs and dances: thirty-five thousand attended on the weekend of 11 May alone.21 For Parisian audiences, the Circassians presented a strange fusion of modern Others from the Russian East, on the one hand, and a living remnant of a prehistoric people from the depths of the Caucasus, on the other. Clearly, the music and dances of the “Circassian caravan” that enchanted the Parisians in 1913 were contemporary forms of folklore, yet they provided an embodied introduction to the same prehistoric Caucasus of Scythian and other tribes that Roerich, Stravinsky, and Nijinsky invoked in Le sacre.22 What the Circassians and numerous other ethnic groups brought to Paris was a sense of visual and sonic authenticity that could be constructed as a bridge to a lost past.

The claim to authenticity had become a trope of Parisian spectacle, whether in exhibitions at the Jardin d’Acclimatation or at the Opéra. To be sure, archaeological and historical fidelity had been one of the distinguishing traits of French stage design since the mid-nineteenth century. In his quest to create as authentic a staging as possible for Camille Saint-Saëns’s Henry VIII, for example, the painter Eugène Lacoste traveled to England, where he visited Hampton Court, Windsor Castle, the Tower of London, and the British Library. His contemporaries considered the result—his famous Tudor sets—as an integral element of the production.23 Whether by way of the Parisian stage sets for Aida at the Opéra in 1880 or those for the Olympia’s Nitokris in 1911, the renewed vogue for all things Egyptian meant that archaeological correctness had become a familiar yardstick in terms of staging.24 Critics touted authenticity as a virtue in their reviews, and journalists could easily enter into learned discussions about the accuracy of the production: mistakes often brought pointed ridicule. In the context of Parisian theater, then, the form of archaeological authenticity claimed for Le sacre by its creators was not only commonplace but was also, by 1913, a far more old-fashioned approach to the stage than either the previous, more Symbolism-inspired contributions of Léon Bakst and Michel Fokine to the Ballets Russes or—where Parisian avant-garde theater was concerned—those productions that spurned realism entirely, as in the infamous but pathbreaking performance of Alfred Jarry’s Ubu roi at the Théâtre de l’Œuvre in 1896.25

In the cultural field constituted by the Parisian elite, the evocation of historical authenticity was also considered a positive aspect for the music of a stage work, wherein signifiers of historical and geographical location served as a valuable music-dramatic device. Witness the work premiered just a month prior to Le sacre, Massenet’s Panurge. The score earned high praise because it derived “numerous effects of a witty and charming color” from the “archaisms” one would expect from such a subject.26 Massenet had perfected the technique of evoking the past through historical forms throughout his career, whether the gavotte in Manon (1884) or the construction of entire scenes around early music idioms, as in Don Quichotte (1910). Other French composers—from Saint-Saëns to Fauré—used similar techniques to evoke the musical past as if it were a foreign country. But if Massenet’s incorporation into Panurge of historical color presented one side of the coin of historicism, the performance of early seventeenth-century music a week later in La délivrance de Renault added to the Parisian soundscape of 1913 the exotic quality of ancient music “whose subtle and archaic harmonies one would love to hear even longer.”27 This Parisian predilection for incorporating historical sound into the local soundscape—whether recomposed for new music or revived in early music performances—thus provided a context for the reception of Stravinsky’s perceived turn to archaic sonorities in Le sacre. Such sonic evocation of the past was fully congruent with what an audience might expect from a prehistoric ballet premiered in Paris.

What critics tried to decide, however, was whether or not Stravinsky’s music should in fact be interpreted through this lens. Georges Pioch, whose review for Gil Blas has been much cited in the literature on Le sacre, expressed the hope that the ballet’s baffling music “was limited exclusively to evoking some of the aspects of Russian prehistory that form Le sacre du printemps.”28 The problem was not the evocation of prehistoric Russia through music that might seem primitive—which would have been appropriate—but the question of whether Stravinsky’s invocation of primitivism in Le sacre had brought about a “premature specimen of the music of the future” better suited to the year 1940.29 For Jean Marnold, on the other hand, the work reflected “a primitive humanity” evoked through a poetic richness that Stravinsky’s music “translated with an intensity of color to which one must submit.” In Marnold’s case, the music posed a question not so much of modernism as of genre: “It was without doubt mainly because it was a ballet that the effort of the composer led to barely more than an exterior art, mostly decorative and picturesque, where the search for effect often seems artificial.”30 Because ballet called for the colorful and the picturesque, Marnold points to a more familiar interpretive perspective, that of the score’s Russian flavor. Thus, critical reception of the music could go in two different directions: either it was universally modern, or it was historically and/or nationally specific.

Massenet’s incorporation of historic French chansons in Panurge lent an acknowledged national air to his Rabelaisian opera that could be celebrated by Parisian critics as a compositional strategy reinforcing local identity. Stravinsky, on the other hand—like any foreign musician in Paris—would be expected to mark his national specificity through sonic means. Here, too, the horizon of expectation was shaped through a cultural practice that distinguished between the long-standing appropriation of exotic materials by French composers, on the one hand, and, on the other, the musical accent—in the sense of Edward Said—that French audiences enjoyed as a distinctive quality in the music of foreigners, whether they lived in Paris, such as Frédéric Chopin, or came for a short visit, like Edvard Grieg.31 In effect, foreigners formed a vital part of the construction of Paris as both French capital and cosmopolitan center. Their roles in the city and its cultural life were first and foremost defined through their participation in its public spheres. While cohabiting in, and navigating, the city’s public and private domains, foreign musicians negotiated a conceptual framework of Self and Other the central dichotomy of which was fundamental to Parisian cosmopolitan nationalism. Foreigners’ participation in Parisian musical life contributed substantially to Parisian identity politics that relied on transnational mediation in fashioning Paris as the cultural center and arbiter of taste of the Western (and colonial) world while nevertheless remaining French through and through.

Audiences and critics played a key role in the construction of such identities by reveling in detecting the national traits perceived in the music of visiting composers, whether German, Russian, or Spanish. The musicians, for their part, often accentuated the sonic markers of their own identity for the Parisian market. Among Stravinsky’s contemporaries, Manuel de Falla’s seven years in Paris between 1907 and 1914 exemplify this dialectical interplay particularly well, in that the composer found himself negotiating “Spanish music” in the French capital. Falla’s exploitation of cultural difference demanded a delicate balancing of autoexoticism and cosmopolitanism while he worked on inserting himself in the Parisian musical avant-garde.32 For Stravinsky and Falla alike, the folkloric cultural capital associated with their respective national identities proved both a blessing and a curse, for it became a stereotype that could easily overwhelm any contribution to the cosmopolitan modernisms of the 1910s. French critics such as Albert Soubies in his 1894 Musique russe et musique espagnole and Jean Marnold in one of his 1911 concert reviews identified an essentialist nationalism as a key element common to both Spanish and Russian musical cultures.33 Yet, at the same time, Falla and Stravinsky were composers in the Western art tradition whose music stood in productive dialogue with Parisian modernity and who engaged with their contemporaries as artistic peers. Thus, these composers’ identity politics formed part of a discourse network that defined—from changing vantage points—both center and peripheries of Western culture at the threshold of modernism.

If Parisian audiences and critics were poised to listen to sonic markers of national identity in concert halls and theaters, musical alterity became even more essentialized in the reception of so-called savages when they were presented in the ethnological exhibits of the Jardin d’Acclimatation or during the Expositions Universelles. At the 1889 Exposition Universelle, for example, audience responses to the arresting and unfamiliar sounds and spectacles ranged from rapt attention, in the case of the Javanese gamelan and dancers, to laughter and catcalls, most prominently in the performances of the Vietnamese Théâtre Annamite.34 Indeed, the exquisite dancers and musicians of the kampong javanais had captured the attention of a Paris hungry for authentic artistic encounters at an event at which sonic and performative alterity was perceived as often compromised by such exotic spectacles as the Arabic belly dancers who had populated Parisian music halls since their wildly successful introduction during the previous Exposition Universelle in 1878.

As in the case of stage design for opera and ballet, for which historical or archaeological accuracy was prized by critics and audiences alike, the aristocratic context of the kampong javanais, enhanced by the sophisticated performances of the dancers and gamelan players, served as a signifier not just of authenticity but also of artistic merit.35 In their reviews, numerous critics drew on Western ballet as a context within which to cast the four Javanese dancers. By contrast, the Théâtre Annamite and its music were received with consternation—and all the more so given that the organizers touted the art as the classical theater of Vietnam. To Parisian eyes, the Vietnamese performances evoked nothing aristocratic; instead, they resembled the popular pantomimes played in the local parks. The misapprehension was compounded by a music too strange to permit a reaction such as the more gently fascinated response to the gamelan. Instead, critics characterized the music as a “horrible charivari of saucepan solos accompanied by drums, cymbals, and tramway horns.”36 If the Javanese performances could be cast as reflecting an aristocratic court culture that brought the fantasies of novels and travel literature alive, the Théâtre Annamite was received as a spectacle the music of which ensounded an alien and primitive alterity to Parisian ears as had few others before or after.

Of course, by 1913 the 1889 Exposition Universelle was a quarter century in the past. The effects of these encounters lingered, however, in the minds of Parisian spectators and were periodically reaffirmed, whether in such grandiose events as the next world’s fair in 1900 or the regular exhibitions at the Jardin d’Acclimatation. In 1913 it was the turn of the Caucasian Circassians to take their place in a long line of musical cultures whose difference in their ethnicity and its performance became a selling point in the Parisian market. As a shrewd businessman with over five years of experience in Paris, Diaghilev had a good handle on the local environment. Stravinsky, for his part, saw Paris as the obvious place to bring out a major new work; this shines through, for example, in his letter to Maximilian Steinberg, when he explained that the new ballet “will, of course, be premiered in Paris.”37

Indeed, from its conception to its premiere, Le sacre du printemps tapped into a variety of Parisian proclivities not only insofar as the plot was concerned but also by integrating Stravinsky’s Russian accent into a modernist score.38 Certainly, as we have seen, a ritual related to female sacrifice accorded with a trend in the French capital both in the boulevard theaters and on the stage of the Opéra. The ballet’s prehistoric setting was more original but not without precedent; and the staging, with its rhetoric of authenticity, related to cultural practices cherished by the Parisian establishment. The score’s Russianist modernism—and even its so-called barbarism—played on musical tropes that granted foreign musicians a privileged place in the musical life of the French capital. By all reckonings, then, Le sacre du printemps should have been a success. So why did Parisian audiences respond so negatively, and where did the creators miscalculate?

The reviews of the premiere suggest that Le sacre du printemps went too far for Parisian taste by embodying a racialized primitivism that fit neither the urban performance space of the Théâtre de Champs-Élysées nor the context of sophisticated modernism that had bolstered the earlier successes of the Ballets Russes.39 An intriguing comment in Pierre Lalo’s review of the ballet points in this direction. The critic did not simply employ the usual comparison of Le sacre to the dances of exotic “savages” but referred repeatedly to Eskimos, perhaps the most notorious case of exhibited alterity in the Jardin d’Acclimatation in 1880. Lalo writes: “In their natural state, Eskimo dances are as stylish as those in Le sacre, which resemble them to the point of confusion; neither one nor the other has style, for the simple reason that there is no style in the misshapen, there is no style in barbarism.”40 By invoking Eskimos in their “natural state,” Lalo referred to the way in which indigenous peoples were considered then as living exemplars of a prehistoric people whose languages and habits might come closest to those archaeologically reconstituted ones presented by Nijinsky on the stage. Indeed, the seemingly “natural state” of the dance in Le sacre was the crux of the matter, for in a sophisticated Parisian theater, art carried the burden of cultural transfer and mediation.41 And so, as Gaston de Pawlowski explained in his review of the ballet, an appropriate form of spectacle would have been one that translated into the artistic language of the target audience the results of any historic and archaeological research, instead of styling them as unmediated materials, for such unmediated materials were best viewed in a different anthropological space that allowed a wider range of responses.42 Whereas at the 1889 Exposition Universelle, for example, the kampong javanais framed the delicious Otherness of the four Javanese dancers and their music, prehistoric Russians lacking a similar contextualization would not be easily accepted at the Théâtre des Champs-Élysées. The presumably “natural” expressions found in Le sacre could thus meet with exactly the same reaction accorded the Théâtre Annamite during the 1889 Exposition Universelle: laughter and catcalls.

However, the issue was more closely related to Nijinsky’s choreography than to Stravinsky’s music and Roerich’s scenery, both of which drew more positive comments, and not only in those reviews that praised Stravinsky as the messiah of new music, such as the oft-quoted idolatry from Florent Schmitt.43 Stravinsky might have played on his Russianness—indeed, we have seen that Paris expected him to do so—but he was also viewed as integrating into his score vital French qualities, not the least of which were its clarity and simplicity. Indeed, those aspects of Stravinsky’s music in Le sacre that evoked the notion of simplicity—whether in his orchestration or in the repetition of short and clearly identifiable segments—were not at all what made the music Russian in the minds of the audiences and critics. Simplicité and clarté are often used as shorthand to designate truly French qualities, and contemporary reviews suggest that by foregrounding the implicitly French qualities of his Russian heritage, Stravinsky reached his target audience. His use of elements that could be considered pivots between the two musical traditions cast the composer as a cultural mediator translating Russian idioms for his local audience.44

Le sacre du printemps and its reception are therefore more complex than we have often assumed. The ballet inhabits what Stephen Greenblatt has called a “contact zone” of cultural mobility, even if the contact points did not quite touch.45 However much we might allow for the nationalist impetus behind its Russian creators, Le sacre du printemps also aspired to be a ballet for Paris, even if it did not succeed as such. Yet Diaghilev and his collaborators misjudged the expectations of urban Paris by bringing seemingly unmediated ethnographic exhibitions into the world of Parisian theaters. The local elite found the ballet transgressive because of, rather than despite, its modernist claims. Paris—so Lalo and numerous other critics claimed—was the capital of style and elegance. Diaghilev had played the game, often to his advantage; but in Le sacre he presented his troupe as embodying a form of difference that, for Parisians, belonged in the zoo, just like the Circassians from the Caucasus who could be admired at the Jardin d’Acclimatation at the same time the ballet had its premiere.46 The creators of Le sacre du printemps might eventually have felt vindicated by history, but on 29 May 1913 they missed their mark.

1. “Le sacre du printemps,” Le Figaro, 29 May 1913. The complete press release reads:

Le Sacre du printemps, que les ballets russes créeront ce soir au théâtre des Champs-Élysées, est la réalisation la plus surprenante qu’ait jamais tentée l’admirable troupe de M. Serge de Diaghilew. C’est l’évocation des premiers gestes de la Russie païenne suscitée par la triple vision de Strawinsky, poète et musicien, de Nicolas Roerich, poète et peintre, et de Nijinsky, poète et chorégraphe. On y retrouvera puissamment stylisées les attitudes caractéristiques de la race slave prenant conscience de la beauté à l’époque de la préhistoire. Les prodigieux danseurs russes étaient seuls capables d’exprimer ces balbutiements d’une humanité demisauvage, de composer ces grappes humaines frénétiques que foule inlassablement la plus éblouissante polyrythmie qui soit sortie d’un cerveau de musicien. Il y a là vraiment un frisson nouveau qui soulèvera sans doute des discussions passionnées, mais qui laissera à tous les artistes une impression inoubliable.

The press release was also published in Le petit journal and Le Gaulois. This and most other reviews I cite in this essay have been compiled in Bullard, “The First Performance.” Volume 2 contains English translations of the reviews, volume 3 the French originals. This collection of reviews overlaps to a significant extent with Lesure et al., Igor Stravinsky, “Le sacre du printemps”: Dossier de presse. Given the typographical errors in Bullard’s anthology, I cite either the originals or the Lesure edition whenever possible.

2. In her foundational study on the Ballets Russes, Lynn Garafola has made the related point that the founding of the company and its character “appear as logical responses to the marketplace” (Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes, 177).

3. Dates of the performances are based on the calendars and reviews published in the French press for that period, in particular in Le ménestrel and Le Figaro.

4. “Le sacre du printemps,” Le Figaro, 29 May 1913; complete press release cited in note 1.

5. Acocella, “The Reception of Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes,” 331. On the role of primitivism and barbarism in the reception of Le sacre du printemps, see also Berman, “Primitivism,” 63–117. For an excellent assessment of Parisian musical exoticism around 1913, see Kelly, Music and Ultra-modernism in France, 95–98.

6. Esteban Buch (citing Garafola, Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes, 293) discusses ways in which the dress rehearsal contributed to the construction of the so-called scandal both at the time and through the reception of the event; see “The Scandal at Le Sacre,” 70–71.

7. Johnson, Listening in Paris, 4.

8. “[U]n événement aussi considérable que la 1re de Pelléas” (Maurice Ravel to Lucien Garban, 28 March 1913, in Ravel, Lettres, écrits, entretiens, 126). For an assessment of the scandal and its immediate and long-term impact, see Buch, “The Scandal at Le Sacre.” Richard Taruskin, on the other hand, considers the press coverage as “huge” in Stravinsky and the Russian Traditions, 2:1007. Compared to the dossiers de presse scholars have assembled on key premieres in Paris, however, the sixty reviews of Le sacre— most of which were written months after the premiere—as collected by Truman Bullard represent an average and unremarkable response.

9. On the Parisian context of the Ballets Russes in terms of both performance and reception, see Caddy, The Ballets Russes and Beyond.

10. Taruskin, Stravinsky and the Russian Traditions, 2:1006. My interpretation does not invalidate any of this Russia-focused research but contextualizes the ballet in its more immediate cultural framework of creation and reception.

11. The discussion of dance owes a significant debt to three generous colleagues: Marian Smith, Helena Kopchick Spencer, and Sarah Gutsche-Miller. For a brief examination of Les bacchantes, see Caddy, The Ballets Russes and Beyond, 55–57.

12. On the Parisian revival of Gluck, see Gibbons, Building the Operatic Museum, esp. 83–119.

13. “Tout s’abat sur la danseuse qu’importe un délire infernale” (Robert d’Humières, “La tragédie de Salomé,” scenario reproduced in the orchestral score for the reorchestrated concert version of 1911, in Schmitt, La tragédie de Salomé, n.p.). I am grateful to Scott Messing for pointing me to this connection.

14. My reference to “feminine endings” evokes the feminist critique of operatic and balletic emplotment in McClary, Feminine Endings.

15. I am grateful to Scott Messing for this idea. Another intertextual reference to Wagner in Le sacre is, of course, the opening bassoon solo, which echoes the English horn in Tristan und Isolde. See Fauser, “Histoires interrompues.”

16. Gutsche-Miller, “Pantomime-Ballet.”

17. Information on both Fumées d’opium and Nitokris comes from ibid., app. B.

18. On “human zoos,” see Bancel et al., Zoos humains.

19. I have addressed these issues, including the construction of music from Africa and the Far East as “timeless” and early incarnations of modern sound, extensively in chapters 4 and 5 of my Musical Encounters.

20. “Au Jardin d’Acclimatation,” Le Figaro, 28 May 1913.

21. “Malgré un temps plutôt défavorable, dimanche et lundi, 35.000 personnes ont défilé sur la grande pelouse où sont campé les Tcherkesses caucases” (Despite the rather unpleasant weather, 35,000 people have paraded across the Great Lawn on Sunday and Monday, where the Caucasian Circassians are camped out) (“Jardin d’Acclimatation,” Le matin, 14 May 1913).

22. Few went so far as Adolphe Bloch, who conducted anthropological studies on the Circassians of the Jardin d’Acclimatation and reported on them in a meeting of the Société d’anthropologie; see his “De l’origine et de l’évolution.” Scholarly interest in the Caucasus was fueled by the search for Caucasian prehistoric ancestors, in part by virtue of its being one putative location for the Garden of Eden. As Bloch put it rather bluntly: “Tout le monde sait que le Caucase a été longtemps considéré comme étant le milieu d’où était sortie la race blanche d’Europe et d’Asie” (Everyone knows that the Caucasus has long been considered the area from where the white race of Europe and Asia originated) (ibid., 430). Esteban Buch explores in some detail how prehistory was constructed in Paris in the early twentieth century and its presence in fiction and popularizing literature; see “The Scandal at Le Sacre,” 72–74.

23. Wild, “Eugène Lacoste.”

24. Over the course of the nineteenth century, Egyptomania swept through Paris in several waves, starting with Napoleon’s campaign in Egypt (1798–1801). The fin de siècle vogue for Egypt was launched by the opening of the Suez Canal in 1869. See Humbert, L’Égyptomanie. Gutsche-Miller (“Pantomime-Ballet,” app. B) indicates that the staging of Nitokris claimed authenticity as being based on museum studies. A tongue-in-cheek review in Le journal amusant gives credit to the staging: “La mise en scène est aussi lumineux qu’égyptienne, les costumes merveilleux et les décors évoquent le sphinx impénétrable et les vieilles pyramides du haut desquelles quarante et un siècles nous contemplent” (The staging is as luminous as it is Egyptian, the costumes are marvelous, and the sets evoke the impenetrable sphinx and the ancient pyramids, from the heights of which forty-one centuries contemplate us) (Le Moucheur de Chandelles, “Olympia—Nitokris,” 11).

25. Louis Vuillemin refers to the premiere of Ubu roi as a positive predecessor to Le sacre du printemps’s modernism. See his contribution to Pawlowski, Vuillemin, and Schneider, “‘Le sacre du printemps,’” given in Lesure et al., Igor Stravinsky, “Le sacre du printemps,” 22.

26. “Le sujet s’inclinait naturellement à quelques velléités d’archaïsme. Massenet, sans en abuser, n’a point manqué d’en tirer mains effets d’une couleur spirituelle et charmante” (The subject was naturally suited to try one’s hand at archaisms. Without going overboard, Massenet did not miss the opportunity to create numerous effects of a witty and charming color) (Quittard, “Théâtre de la Gaîté-Lyrique”). I have discussed the role of historic color in Massenet’s music in “Musik als ‘Lesehilfe.’”

27. “[C]ar on en écouterait volontiers plus longtemps les harmonies fines et archaïques” (Tiersot, “Semaine théâtrale,” 147).

28. “[É]tait exclusivement limitée à l’évocation des quelques aspects de la préhistoire russe qui compose le Sacre du printemps” (Pioch, “Théâtre des Champs-Élysées,” given in Bullard, “The First Performance,” 3:27).

29. “[U]n spécimen prématuré de la musique de l’avenir” (Vallas, “Le sacre du printemps,” given in Lesure et al., Igor Stravinsky, “Le sacre du printemps,” 29).

30. “[U]ne humanité primitive . . . tout ce que rêva le poète est traduit par cette musique avec une intensité de couleur à laquelle on doit céder. . . . Sans doute est-ce surtout parce qu’il s’agissait d’un ballet, que l’effort du musicien n’aboutit guère ici qu’à un art extérieur, avant tout décoratif et pittoresque, où la recherche de l’effet semble souventefois artificielle” (Marnold, “Musique; Ballets Russes,” given in Bullard, 3:226–27). The complex discourse around the ornamental in Le sacre and its intersection with Parisian musical culture is explored in Bhogal, Details of Consequence, 212–67.

31. Said introduced the concept of “accent” as an ineluctable and powerful element in the artistic production of an artist writing in a foreign language. He developed the concept while studying Joseph Conrad. See, among others, Said, “No Reconciliation Allowed”; Said, Reflections on Exile.

32. Llano, Whose Spain?, 136–51. Autoexoticism refers to subaltern artists exoticizing themselves and their culture not only in producing art for external markets but also by internalizing stereotypes in fashioning their own musical identities.

33. Ibid., 46–47.

34. Fauser, Musical Encounters, 165–95.

35. While some of the issues are familiar from the “human zoos,” the reception of the kampong javanais was framed within different discourse networks, not least because of its location in a colonial exhibition rather than a zoo.

36. Fauser, Musical Encounters, 189.

37. Igor Stravinsky to Maximilian Steinberg, 10 August 1912, given in Meyer, “Chronology (1910–1922),” 451.

38. That Stravinsky was strongly embedded in his Parisian context has been addressed by, among others, Dufour in Stravinski et ses exégètes and Levitz in Modernist Mysteries. Stravinsky’s engagement with the artistic marketplace remained in operation also during his American years. See, for example, the contextualization of the Dumbarton Oaks Concerto in Brooks, The Musical Work of Nadia Boulanger, 224–50.

39. Compare Tamara Levitz’s essay in this volume.

40. “Les danses des Esquimaux, à l’état naturel, ont exactement autant de style que celles du Sacre, qui leur ressemblent à s’y méprendre; et ni les unes ni les autres n’ont de style, pour cette raison toute simple qu’il n’y a pas de style de l’informe, qu’il n’y a pas de style de la barbarie” (Lalo, “Considérations sur le ‘Sacre du printemps,’” given in Lesure et al., Igor Stravinsky, “Le sacre du printemps,” 33; see also Buch, “The Scandal at Le Sacre,” 73).

41. Cultural transfer and mediation in French opera and ballet are addressed in the contributions to Fauser and Everist, Music, Theater, and Cultural Transfer.

42. “Lorsqu’un littérateur comme J.-H. Rosny nous décrit avec une vérité saisissante la vie de peuplades primitives, il n’écrit point son roman dans la langue de l’époque, il ne nous offre pas une suite d’onomatopées bizarres et rudes: il écrit en belle langue française” (When a scribbler such as J.-H. Rosny describes for us with a piercing truth the life of primitive peoples, he does not write his novel in the language of that period, nor does he offer us a sequence of bizarre and crude onomatopoeia: he writes in beautiful French) (G[aston] de Pawlowski, in Pawlowski, Vuillemin, and Schneider, “‘Le sacre du printemps,’” in Lesure et al., Igor Stravinsky, “Le sacre du printemps,” 19). Berman (“Primitivism and the Parisian Avant-Garde,” 97) cites this extract but does not discuss its implications for the reception within a Parisian context.

43. Taruskin makes the important point that “the role of Stravinsky’s music in bringing about the scandal has been systematically exaggerated” (Stravinsky and the Russian Traditions, 2:1007); Bhogal (Details of Consequence, 212–67) offers a convincing analysis that shows the intimate connection of Le sacre to compositional procedures deployed by both Debussy and Ravel. Vuillemin observes this connection in his review of the score in Comœdia (Pawlowski, Vuillemin, and Schneider, “‘Le sacre du printemps,’” in Lesure et al., Igor Stravinsky, “Le sacre du printemps,” 22), where he writes that Stravinsky “doit énormément à ses ancêtres, les musiciens russes. Il doit beaucoup à quelques musiciens français” (owes his ancestors, the Russian musicians, enormously. He owes a great deal to some French musicians).

44. Reminiscing about the Ballets Russes, Alexandre Benois, one of the company’s stage designers, pointed out that “our simplicity revealed itself in Paris as something more refined, developed, and subtle than the French themselves could do” (given in Acocella, “The Reception,” 330).

45. Greenblatt, “A Mobility Studies Manifesto,” 251.

46. Garafola points out that, despite the fact that Le sacre du printemps was “probably Diaghilev’s most profoundly Russian work of the prewar years,” fewer than half of his dancers that season were actually “identifiably Russian.” Yet for the purpose of the performance of national identity in Paris, Russianness “could be impersonated, passed on to bodies that hailed far from the Neva” (Garafola, “Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes,” 38–39). See also Lynne Garafola’s essay in this volume, esp. note 15.