Six pages of the orchestral sketches for the ballet Le sacre du printemps reside in the Fyodor and Igor Stravinsky Collection at the National Library of Russia in St. Petersburg (see Figures 12.1–6).1 In her book Mir Stravinskogo (The world of Stravinsky), Svetlana Savenko reproduced only one page from these manuscript materials (the recto of sheet 1; see Figure 12.1), with minimal comment.2 In 2013 the Paul Sacher Foundation published three more pages (the recto and verso of sheet 3 and the verso of sheet 4; see Figures 12.4–6).3 However, if seen in their entirety, these six pages offer scholars the opportunity to study changes in orchestration as entered by Stravinsky into the fair copy of Le sacre du printemps just before he completed the final score. In this essay, I will describe and interpret all of the sketches and compare aspects of them with the final version (i.e., the orchestral score of 1913). In addition, I will explain the circumstances under which these documents found their way into the National Library of Russia.

Le sacre’s orchestral sketches were made with a lead pencil on four large sheets of score paper (13.5" × 17.1") with twenty-eight staves on the page. Each of the documents appears to be in rather good condition, except for a deep fold on the first of the four sheets (see Figure 12.1). Stravinsky did not date, paginate, or sign these materials. Moreover, the sheets contain no comments on the programmatic meaning of the sketches or on their narrative positioning in the ballet.

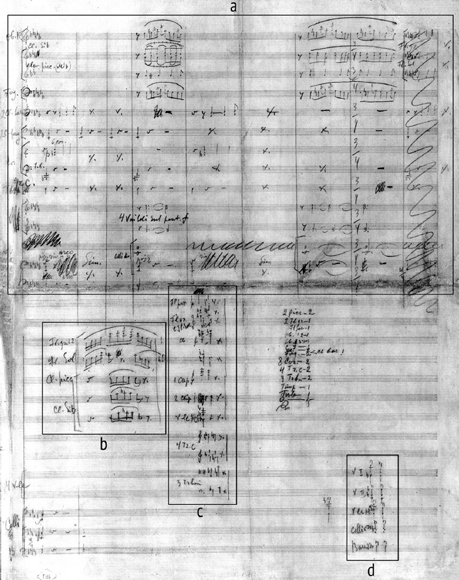

In Mir Stravinskogo, Savenko identified the contents of four of the sketches as related to the “Rondes printanières” (see the excerpts in the squares shown in Figure 12.1). They comprise the following:

1. Figure 12.1a: R-49:1–8

2. Figure 12.1b: R-54:4

3. Figure 12.1c: R-55:1

4. Figure 12.1d: R-54:5

Sketches for another three movements follow those for “Rondes printanières”:4

“Jeux des cités rivales” (on the verso of the first and the verso of the second sheet):

1. Figure 12.2: R-57:1–6

2. Figure 12.3: R-62:1–6

“Glorification de l’élue” (on the recto and verso of the third sheet):

1. Figure 12.4: R-104:1 through R-105:1

2. Figure 12.5: R-105:3 through R-106:2

“Cercles mystérieux des adolescents” (on the verso of the fourth sheet):

1. Figure 12.6: R-103:1–2

The rectos of sheets 2 and 4 are left blank—perhaps deliberately to allow for additional sketches.

Taken as a whole, these six pages of sketches concern the orchestration of thematic segments, detached chords, ostinato blocks, and connecting sections within the form. For example, the largest concentration of components functioning as part of the theme’s mosaic structure in the “Rondes printanières” can be seen in Figure 12.1. The initial subject of the main section (designated a in Figure 12.1) is juxtaposed with another three tiny episodes in the Vivo section of the final score to which the orchestration is attached (designated b, c, and d in Figure 12.1). On this same sheet, there is a calculation of the staves with the names of the instruments in the score, showing Stravinsky’s central concern for instrumentation in all these segments.

As is well known, many marginal notes, drawings, and other commentary appear in autographs for Le sacre housed in the Igor Stravinsky Collection at the Paul Sacher Foundation in Basel. By contrast, these sketches do not feature any extramusical details. When he inserted them during the final stages of the creative process, Stravinsky sought to capture his practical ideas for orchestration as swiftly as possible. The nature of his cursive writing shows that these sketches were done in haste, with abbreviations and without any care for the consistency in the naming of instruments (e.g., in Figure 12.1, flauto contralto is labeled “Fl. Sol”; violins are referred to both in Russian, “скр.” [скрипка/skripka], and in Italian, as “v-ni”). Sometimes the very drawing of the musical notation appears imbued with emotion. In the “Glorification de l’élue,” Stravinsky placed heavy pressure on his pencil. Moreover, he made an emphatic strikeout in the frenzied and convulsive main theme (see Figure 12.4) and leaned so heavily on his pencil that crescendo signs look like deeply etched forks (visible on the original sketch; see Figure 12.5).

In general, the content of these sketches differs little from the final version; however, there are two exceptions. In the excerpt from “Rondes printanières” at R-49, the initial chords of the piano horns (Figure 12.1, at “a”) were replaced in the final version with the heavy “flesh” of the strings playing mf on a downbow (sostenuto e pesante); the aim appears to be to avoid all allusions to sweetness. Moreover, in the score of “Jeux des cités rivales” (Figure 12.3), Stravinsky wrote out a long ostinato of pulsing eighth notes that ends on a powerful chord in the winds. In the sketch for this excerpt, this chord is preceded by a brief ascending passage in the two flutes—a typical sound of Le sacre, in which many harmonies are scattered over musical time and space by grace notes, like whirling “pieces of scales” or trills having the effect of musical “clouds of cosmic dust.” However, in this passage, Stravinsky ultimately preferred the mechanically rigid, peremptory stroke of the chord without any anacrusis.

Figure 12.1. Sketch for “Rondes printanières.” Collection 746, Fedor and Igor' Stravinskii, MS101, sheet 1r, National Library of Russia Manuscript Department (NLR MD), St. Petersburg. The square units labeled a, b, c, and d were added by the author. Compare to the score: (a) R-49:1–8; (b) R-54:4; (c) R-55:1; (d) R-54:5. The Rite of Spring by Igor Stravinsky © Copyright 1912, 1921 by Hawkes & Son (London) Ltd. Reprinted by permission of Boosey & Hawkes, Inc.

Figure 12.2. Transcription of the sketch for “Jeux des cités rivales.” Collection 746, Fedor and Igor' Stravinskii, MS101, sheet 1v, National Library of Russia Manuscript Department (NLR MD), St. Petersburg. Compare to the score: R-57:1–6. (Compare a photograph of the original sketch in Figure 12.2 in the print version of this book.) The Rite of Spring by Igor Stravinsky © Copyright 1912, 1921 by Hawkes & Son (London) Ltd. Reprinted by permission of Boosey & Hawkes, Inc.

Figure 12.3. Sketch for “Jeux des cités rivales.” Collection 746, Fedor and Igor' Stravinskii, MS101, sheet 2v, National Library of Russia Manuscript Department (NLR MD), St. Petersburg. Compare to the score: R-62:1–6. The Rite of Spring by Igor Stravinsky © Copyright 1912, 1921 by Hawkes & Son (London) Ltd. Reprinted by permission of Boosey & Hawkes, Inc.

Figure 12.4. Sketch for “Glorification de l’élue.” Collection 746, Fedor and Igor' Stravinskii, MS101, sheet 3r, National Library of Russia Manuscript Department (NLR MD), St. Petersburg. Compare to the score: R-104:1 through R-105:1. The Rite of Spring by Igor Stravinsky © Copyright 1912, 1921 by Hawkes & Son (London) Ltd. Reprinted by permission of Boosey & Hawkes, Inc.

Figure 12.5. Transcription of the sketch for “Glorification de l’élue.” Collection 746, Fedor and Igor' Stravinskii, MS101, sheet 3v, National Library of Russia Manuscript Department (NLR MD), St. Petersburg. Compare to the score: R-105:3 through R-106:2. (Compare a photograph of the original sketch in Figure 12.5 in the print version of this book.) The Rite of Spring by Igor Stravinsky © Copyright 1912, 1921 by Hawkes & Son (London) Ltd. Reprinted by permission of Boosey & Hawkes, Inc.

Figure 12.6. Transcription of the sketch for “Cercles mystérieux des adolescents.” Collection 746, Fedor and Igor' Stravinskii, MS101, sheet 4v, National Library of Russia Manuscript Department (NLR MD), St. Petersburg. Compare to the score: R-103:1–2. (Compare a photograph of the original sketch in Figure 12.6 in the print version of this book.) The Rite of Spring by Igor Stravinsky © Copyright 1912, 1921 by Hawkes & Son (London) Ltd. Reprinted by permission of Boosey & Hawkes, Inc.

The six pages of sketches were written out sometime between 17 November 1912 (the completion date of the four-hand piano version of Le sacre) and 29 March 1913 (the completion date of the orchestral score). The records at the National Library of Russia describing the acquisition of these materials do not address the history, condition, or order of the documents when given to the repository. Only the individual or individuals who sold the manuscripts to the National Library could have commented on those matters. However, in Russia, during the sale of such an artifact, former owners are not legally required to disclose even their names. Documents stating the facts of acquisition remain special in-house data made by and for the staff of an institution. However, I was determined to examine the institution’s documentation to see if it might reveal the identity of the seller or sellers.

After scrutinizing the complete lists of purchases made by the library from 1920 to the early 1980s, I found a reference in the library’s official 1985 catalog to a substantial collection of thirteen “items” purchased in 1981.5 Available evidence dated the items in this collection to the years 1909 to 1914. The library’s catalog mentioned that the collection contained, among many other items, Stepan Stepanovich Mitusov’s libretto for Stravinsky’s opera The Nightingale with Stravinsky’s notes, as well as letters of Igor Stravinsky, Ekaterina Stravinsky, the painter and set designer Nikolai Roerich, and the music publisher Boris Jurgenson—all written to Mitusov (1876–1942), a member of Roerich’s family and one of the composer’s closest friends.

I later found the bill of sale for the collection in the private office files of the library staff. There I first saw the name “Tatiana Mitusova” as the seller, along with the exact date of purchase and the amount paid—571 rubles, an amount roughly equal to two months’ salary of a university professor.6 Tatiana, an engineer (born just weeks before Le sacre’s premiere on 10 May 1913), and her elder sister Liudmila, a painter and teacher, were the daughters of Stepan Mitusov.7 The sisters were the only members of their immediate family to survive the siege of Leningrad and World War II. Thus, during subsequent years, they alone had devotedly cared for their father’s archive at their home on 18 Fourth Sovetskaia Street in the neighborhood of Stravinsky’s former apartment (6 Bolshaia Bolotnaia Street), where he conceived The Nightingale.

Figure 12.7. Photograph of Stravinsky taken at the Gershon Studio in Paris on one of the first three days of June 1913. Collection 746, Fedor and Igor' Stravinskii, National Library of Russia Manuscript Department (NLR MD), St. Petersburg.

I suggest that between approximately 15 and 22 July 1913, Stravinsky gave Mitusov the Sacre manuscripts and two photographs.8 After the premiere of Le sacre at the end of May and a hospital stay in the early summer, Stravinsky and his family finally journeyed to Ustilug in Ukraine on 11 July 1913. Meanwhile, the composer had invited Mitusov to join him there for a week of work on The Nightingale.

I contend that one of the photos, taken at the Gerschel Studio (rue de Prony 5) in Paris (Figure 12.7), is historically significant. It is a rare piece of evidence documenting Stravinsky’s physical and emotional condition after the dramatic turn of events immediately following Le sacre’s premiere. Surprisingly, the picture has been published only once, in the Russian journal Muzykal’naia zhizn’ (Musical life).9 Stravinsky poses in an elegant suit, with a cigarette in his right hand. The white frame of the photo looks as though it was hastily cut off, and it is frayed at the edges. A dedicatory inscription from Stravinsky to Mitusov appears on the matting: “To Stepochka, my dearest friend from Igor’, Ustilug, July 1913, and I was photographed in Paris in June 1913.” Thus, the picture was most likely taken on one of the first three days of June 1913.

Late on 3 June, Stravinsky entered the suburban hospital Villa Borghese. He remained there until early July, when, on 11 July, his family went to Ustilug. It is possible that not only his legendary eating of a “bad oyster” contributed to Stravinsky’s serious illness; the severe stress that he experienced at the Sacre premiere could have weakened his immune system and provoked the onset of a typhoid infection. These horrific experiences surrounding Le sacre’s premiere were indelibly branded on Stravinsky’s psyche for more than half a century. Decades later, he would reiterate his feelings about this time on the last page of Le sacre’s fair score:

Пусть будетъ слушатель этой музыки навсегда обеспеченъ отъ издевательства свидѣтелемъ чего я былъ въ Парижѣ весной 1913 года на премьерѣ балетного представленiя “Le Sacre du Printemps” въ Театрѣ ‘Champs Elysées’ Игорь Стравинский Цюрихъ 11-го окт[ября] 1968 г. [May whoever listens to this music never experience the mockery of which I was the witness at the ballet performance of Le sacre du printemps in the Théâtre des Champs-Élysées, Paris, Spring 1913. Igor Stravinsky Zurich 11 Oct(ober) 1968.]10

I wish to acknowledge the librarians of the Manuscript Department of the National Library of Russia—Drs. Natalia Ramazanova, Irina Vaganova, and Elena Mikhailova—for their kind assistance with this project. An earlier version of this chapter was presented at the conference “Anniversary of a Masterpiece: Centenary of The Rite,” Moscow (Tchaikovsky) State Conservatory, 13–15 May 2013, at the kind invitation of Professor Svetlana Savenko.

1. Collection 746, “Fedor and Igor’ Stravinskii,” MS 101, sheets 1r–4v, National Library of Russia Manuscript Department (NLR MD), St. Petersburg.

2. Savenko, Mir Stravinskogo, 228–29.

3. Stravinsky, Le sacre du printemps. Facsimile of the Autograph Full Score, 42, plates 2a–c.

4. At the request of the National Library of Russia, figures 12.2, 12.5, and 12.6 appear as original sketches in the print version of this book and in transcription in the digital version of this book.

5. Georgieva, Novye postupleniia, 142.

6. I located the transaction, numbered 81–6059, in a log-diary of the library’s purchases.

7. Liudmila Mitusova recorded details of her family’s life in O prozhitom i sud’bakh blizkikh.

8. Collection 746, “Fedor and Igor’ Stravinskii,” MS 103, sheets 1–2, NLR MD.

9. Kazanskaia, “Stravinskii i Mitusov,” 33.

10. The original version of Stravinsky’s inscription has been deliberately quoted here because its published variants contain misreadings and errors.