Igor Stravinsky described the opening section of his Rite of Spring as a “swarm of spring pipes.”1 This interpretation links The Rite to idylles antiques choreographed and presented by the Ballets Russes: Maurice Ravel’s Daphnis and Chloé and Claude Debussy’s L’après-midi d’un faune (both of which begin with melodies in the winds). Indeed, twentieth-century French music evolved from the pastoral—as Debussy famously asserted with his declaration “Long live Rameau! Down with Gluck!”2 In Russia, Mikhail Bakhtin described the idylle as “elemental” in character, “the combination of human life with the life of nature, the unity of their rhythm, [and] a common language for the phenomena of nature and the events of human life.”3 The “elements” (in Russian, stikhii) have long been the subject of the arts, including music. However, in 1909, at the time of The Rite’s conception, the subject of the “elements and culture” (stikhiia i kul'tura) had become central in the thought of the Russian intelligentsia, who interpreted this topic as related to the politics of national identity. In this essay, I will comment on the role of the “element” in The Rite and its origins and meanings in opera-ballet of the French Baroque and in Russian fin de siècle music and culture.

In French opera, the word “element” first appeared as a title in André Cardinal Destouches’s opéra-ballet Les élémens (The elements) (1721); each of its four acts (entrées) presents a different love affair, presided over by Air, Water, Fire, and Earth, respectively. Subsequently in French ballet, Jean-Féry Rebel took up an analogous topic in his Les élémens (1737), the first such French dance production without singers. Rebel’s plot centers on musical interpretations of the four elements. Later French works combined the notion of the elements with Orientalism. For example, in the opera-ballet Les Indes galantes (The amorous Indies) (1735) by Jean-Philippe Rameau, each section has a local flavor of its own and is often associated with the exotic expression of a particular element: “The Gracious Turk” is associated with Water and a storm at sea; “The Incas of Peru” with Earth and volcanic eruption; “The Flowers,” the tale of a Persian love triangle, with Fire and Air. Thus, in the early years of the Ballets Russes, Diaghilev would rely on a tradition of the Parisian taste for the exotic in his choice of subject matter. And indeed, in Paris The Rite’s “scenes from pagan Russia” could even be interpreted as a reinvention of a ballet entrée in the exotic manner of Rameau’s Les Indes galantes.

By contrast, in Russian culture of the Silver Age, the “elements” were most frequently associated with aspects of political conflict and violence. In September 1908 Andrei Belyi employed a “volcanic” metaphor, writing that “Russia is pregnant with revolution. . . . Forerunners of the explosion already roam through towns and villages. I hear them, but the deaf do not, and the blind do not see them, the worse for them. . . . The explosion is inevitable. The volcano will be opened by people of flint, smelling of fire and brimstone!”4 A similar idea appears in Alexander Blok’s lecture to the Religious Philosophical Society on 30 December 1908 / 12 January 1909, in which the poet alludes to the Italian earthquake of Messina to prophesy a revolution between religious sectarians and the intelligentsia: “People of culture . . . move scholarship forward in secret malice, trying to forget and not to hear the roar of the elements of the earth and of the subterrestrial. . . . There are other people. . . . The Earth is with them, and they are with the earth, and they are indiscernible on her bosom.”5

The key image of Blok’s lecture is the earthquake, but his main subject is “the people and the intelligentsia,” understood metaphorically as “the elements and culture,” whereby the sectarians exert “subterrestrial” pressure on the cultivated “crust” of Russian society: “Are we sure that the crust is hard enough to withstand the other, similarly terrible element [stikhiia], not subterrestrial, but earthly—the people [narod]?”6 This controversial metaphor became “the symbol of a national idea.”7 Indeed, Stravinsky would create his own explosive connections between the elements and the people in The Rite.

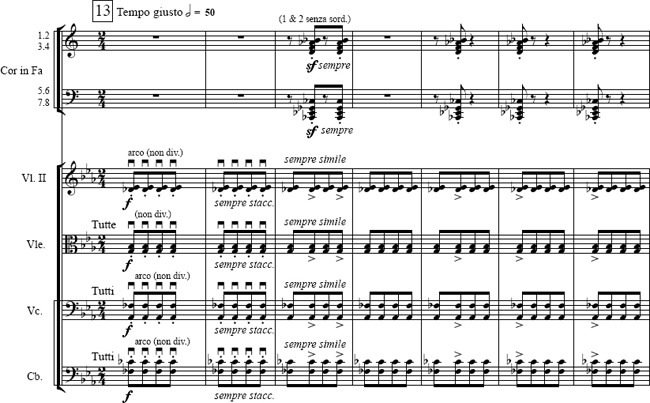

The Earth is the element of the first part of Stravinsky’s ballet. Beginning with the first measure (R-13:1), the “Augurs” chord is sounded multiple times in an ostinato with irregular accents (see Example 16.1).

Multiple repetitions of a sound are a time-honored way of representing phenomena related to the element of Earth, a rhetorical figure actively used in the Baroque and later—up to Franz Joseph Haydn’s Creation. The figure, a kind of vibrato technique, was termed Bebung (i.e., “trembling”) in treatises of the time.8 This musical symbol accounts for hundreds of examples in the music of Haydn, Johann Sebastian Bach, Georg Friedrich Handel, Georg Philipp Telemann, Rameau, Marin Marais, Rebel, Christoph Willibald Gluck, and Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart.9 The figure is used as a topos for the internal shivering and trembling of the soul, for existential fear, or for the literal trembling of the earth.

Example 16.1. Igor Stravinsky, The Rite of Spring, “The Augurs of Spring” at R-13. The Rite of Spring by Igor Stravinsky © Copyright 1912, 1921 by Hawkes & Son (London) Ltd. Reprinted by permission of Boosey & Hawkes, Inc.

The presentation of the “Augurs” chord mirrors the examples of French Baroque music utilizing the Bebung effect. For example, Rebel, in Les élémens, represents the character of Chaos with a highly dissonant passage reminiscent of The Rite (see Example 16.2). Moreover, the composer indicates instances of “the elements” in his score. Rebel writes: “The bass portrays the [Creation] of the Earth: long notes should be played sharply and convulsively. . . . The flute slides ascending and descending depict the murmur of Water. The Air is presented by long sustained notes. Finally, quick and brilliant violin passages correspond to the liveliness of Fire. Those distinctive features are clearly identifiable—separate or combined, whole or in part.”10

Example 16.2. Jean-Féry Rebel, “Chaos,” the opening section of the ballet Les élémens (The elements), mm. 17–23.

Example 16.3a. Jean-Philippe Rameau, Les Indes galantes (The amorous Indies), entrée 2, “Tremblement de la terre” (The trembling of the earth), mm. 1–4.

By comparison, in Rameau’s Les Indes galantes, act 2, the ostinato’s repetition forms a musical figure depicting the beginning of an earthquake and volcanic eruption, as indicated by the stage directions (see Example 16.3a). Furthermore, as with Stravinsky in the case of the “Augurs” chord, Rameau composed a dissonant, polyharmonic structure to represent the trembling of the Earth; the bass line sustains the pedal tonic F below a harmonic figuration on the dominant. Swift scale figures correspond to flashing spurts of flame from the volcanic crater, the element of Fire (see Example 16.3b).

Stravinsky clearly shared the same awareness of musical topoi. The score of his cantata Zvezdolikii (Le Roi des étoiles, or The King of the Stars), composed contemporaneously with The Rite, gives a sense of his complete mastery of musical illustration through specific figures associated with the text. Examples 16.4a and 16.4b show

Stravinsky’s settings recall those of Rameau’s motet Deus noster refugium—in particular, the “trembling” rhythmic pulsation at the words “the earth be removed” (Example 16.5). Similar textures can be observed in Rameau’s opera Hippolyte et Aricie (Example 16.6a–f). The Bebung figure is part of a complex multilayered structure in the first two measures: ascending scales (called, in the Baroque, an anabasis figure);12 wide leaps (i.e., the Baroque’s saltus duriusculus);13 rhythmic patterns of “trembling” (i.e., the repetition of a G minor triad with punctuated rhythms);14 as well as tmesis (i.e., a double-punctuated rhythm with a pause in the pattern) (Example 16.6a).15 A cell having the overall value of four sixteenth notes is the source of the “trembling” pattern (Example 16.6b). After further development, this initial rhythmic symbol of “trembling” is isolated by rests and reduced to a single cell (Example 16.6c). Then the cell grows more and more insistent in its repetition (Example 16.6d). The text then turns imperative (“Tremble, shake with fear”), and the rhythmic pattern of “trembling” completely controls the texture (Example 16.6e). The role of passus duriusculus in the climax of the scene cannot be underestimated: the descending chromatic scale in the melodic line is even highlighted through doubling with minor triads (Example 16.6f).16

Chorus:

In the depths of the earth

The winds have declared war.

[The air has become dense and dark, the trembling of the earth doubles, the volcano lights up and spits flashes of fire and smoke.]

Burning rocks are thrown into the air,

And carry the flames of hell to the heavens.

Example 16.3b. Rameau, Les Indes galantes, entrée 2, “Tremblement de la terre,” mm. 12–14.

Example 16.4a. Stravinsky, Zvezdolikii (Le roi des étoiles, or The King of the Stars), mm. 13–14. Moscow: Kompozitor, 1996.

Example 16.4b. Stravinsky, Zvezdolikii, m. 21. Moscow: Kompozitor, 1996.

Therefore we will not fear, though the earth be removed (turbabitur terra), and though the mountains be carried into the midst of the sea. (Psalm 46:2)

Example 16.5. Rameau, Deus noster refugium (God, our refuge), trio, “Propterea non timebimus” (Therefore we will not fear), mm. 1–10.

Example 16.6a. Rameau, Hippolyte et Aricie, act 2, scene 5, “Trio des Parques” (Trio of the Fates), mm. 1–3.

Example 16.6b. Rameau, Hippolyte et Aricie, act 2, scene 5, “Trio des Parques,” mm. 2–3.

Example 16.6c. Rameau, Hippolyte et Aricie, act 2, scene 5, “Trio des Parques,” mm. 11–14.

Example 16.6d. Rameau, Hippolyte et Aricie, act 2, scene 5, “Trio des Parques,” mm. 31–33.

Example 16.6e. Rameau, Hippolyte et Aricie, act 2, scene 5, “Trio des Parques,” mm. 34–36.

Example 16.6f. Rameau, Hippolyte et Aricie, act 2, scene 5, “Trio des Parques,” mm. 31–36.

Чернобогъ, Кащей, Морена. Шабашъ духовъ тьмы

Scène III.

Tchernobog, Kaschtchey (l'homme-squelette) Moréna. Sabbat des Esprits infernaux.

Example 16.7a. Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov, Mlada, act 3, scene 3.

Example 16.7b. Rimsky-Korsakov, Mlada, act 3, “Ronde infernale” at R-22.

Before comparing Rameau’s score and Stravinsky’s Rite, it is crucial to recognize that figures in Rimsky-Korsakov’s “Ronde infernale” (Adskoe kolo), in a scene from act 3 of the opera Mlada, look both back to Baroque topoi and forward to The Rite. The scene takes place at night on Triglav Mountain; the main element—the Earth, or, more precisely, the volcanic Earth, bursting with subterrestrial infernal elemental forces—motivates Rimsky-Korsakov’s use of multiple ostinato Bebung/“trembling” figures of different kinds. The composer’s stage directions directly assert the meaning of the musical device: “subterrestrial roar and thunder, in orchestra only” (Example 16.7a).

A comparative analysis of Rimsky-Korsakov’s operatic scene and the “Augurs of Spring” in The Rite (R-13:1 and following) reveals striking similarities (compare Example 16.7b with R-13):

Part II of The Rite is laden with figures of “trembling,” from the very upbeat to the “Glorification of the Chosen One” (Example 16.8a) to the cadence of the “Sacrificial Dance.” However, the “trembling” here is just one component in a multilayered complex structure. For example, in the opening of the “Glorification of the Chosen One” (functioning as a Grundgestalt), the “trembling” pattern is combined with ascending passages (flutes), salti duriusculi (i.e., wide leaps), and tmesis (i.e., the pattern with pauses) (Example 16.8b).

Later, the “trembling” figure is presented in different patterns, various metric units, and contrasting orchestrations, not simply as a regular pulse in the lowest line of the musical texture, but rather as embodying an emotional and psychological sense of trembling with fear.

The similar short “trembling” motive, analyzed earlier in an example by Rameau, is present in the “Sacrificial Dance” (Example 16.9). The figure is moved from the upbeat to the strong beat, reduced to sixteenth notes separated by rests, and combined with passus duriusculus, which is gradually transformed from a semitone lamento motive to a descending full chromatic scale—also a gesture in Rameau’s “Trio of the Fates” from Hippolyte et Aricie (see Examples 16.6f and 16.10a–b).

Example 16.8a. Stravinsky, The Rite of Spring, R-102:3 leading to the “Glorification of the Chosen One” (at R-104). The Rite of Spring by Igor Stravinsky © Copyright 1912, 1921 by Hawkes & Son (London) Ltd. Reprinted by permission of Boosey & Hawkes, Inc.

Example 16.9. Stravinsky, The Rite of Spring, “Sacrificial Dance” at R-149; Rameau, Hippolyte et Aricie, act 2, scene 5, “Trio des Parques,” m. 2. The Rite of Spring by Igor Stravinsky © Copyright 1912, 1921 by Hawkes & Son (London) Ltd. Reprinted by permission of Boosey & Hawkes, Inc.

Example 16.8b. Stravinsky, The Rite of Spring, “Glorification of the Chosen One,” R-104:1 through R-105:1. The Rite of Spring by Igor Stravinsky © Copyright 1912, 1921 by Hawkes & Son (London) Ltd. Reprinted by permission of Boosey & Hawkes, Inc.

Example 16.10a. Stravinsky, The Rite of Spring, “Sacrificial Dance” at R-149. The Rite of Spring by Igor Stravinsky © Copyright 1912, 1921 by Hawkes & Son (London) Ltd. Reprinted by permission of Boosey & Hawkes, Inc.

Example 16.10b. Stravinsky, The Rite of Spring, “Sacrificial Dance” at R-181. The Rite of Spring by Igor Stravinsky © Copyright 1912, 1921 by Hawkes & Son (London) Ltd. Reprinted by permission of Boosey & Hawkes, Inc.

Example 16.11. Stravinsky, The Rite of Spring, Introduction to Part II, R-86:2 through R-87:3, modification of the “trembling” rhythmic pattern (added to the score in March 1913). The Rite of Spring by Igor Stravinsky © Copyright 1912, 1921 by Hawkes & Son (London) Ltd. Reprinted by permission of Boosey & Hawkes, Inc.

While working on the draft of The Rite, Stravinsky wrote to his collaborator, Nikolai Roerich, “I believe that I penetrated the mystery of the spring lapidary rhythms and felt and sensed [voschuvstvoval] them together with the characters of our brainchild.”17 Later, in a letter to Nikolai Findeizen, he associated the “lapidary” rhythm with the element (stikhiia) of the Earth: “I make them feel in the lapidary rhythms the proximity of people to the earth, their common life with the earth.”18 And indeed, one simple rhythmic figure (the cell with two sixteenth notes) is an example of such a lapidary rhythm.19 Having established its Baroque genesis (see Example 16.6b), we can identify this rhythmic pattern as associated with topoi of fear and awe in The Rite (Example 16.11).

Such hermeneutics of rhythm and the interpretation of rhetorical patterns and their combinations allow us to interpret some of the basic musical concepts of The Rite. And indeed, comparative analyses of above-mentioned examples by Rebel, Rameau, Rimsky-Korsakov, and Stravinsky offer a means to identify similar topoi presenting furious elements in all of their works. The expressive similarities parallel a sameness of narrative: location on the boundary of the terrestrial and subterrestrial domains, the invocation of sinister primal forces, the readiness to perform self-sacrifice in light of them, and the verdict of the Fates.20 Thus, through the use of these topoi, Stravinsky shaped The Rite of Spring as a work that simultaneously looks back to the traditions of French and Russian music and culture and reinvents them for the twentieth century.

1. According to the composer’s definition, “The orchestral introduction is a swarm of spring pipes”; see Igor Stravinsky to Nikolai Findeizen, 2/15 December 1912, in Varunts, I. F. Stravinskii, 1:387.

2. Debussy made his famous statement at a performance of the pastoral ballet La guirlande, ou Les fleurs enchantées (1751), by Jean-Philippe Rameau, an Enlightenment idylle on a typical galant story about a loyal shepherdess; see Laloy, Debussy, 83.

3. Bakhtin, “Formy vremeni i khronotopa v romane,” 258.

4. Valentinov, Dva goda s simvolistami, 281.

5. Blok, Stikhiia i kul'tura, 2:98–99.

6. Ibid., 2:97.

7. Ivanov, O russkoi idee, 327.

8. See, for example, “§88 Von der Bebung,” in Türk, Clavierschule, 293.

9. See, for example, the recitative of the Evangelist during the Golgotha earthquake in J. S. Bach’s St. Matthew Passion, BWV 244: “Und die Erde erbebete, und die Felsen zerrissen” (And the earth quaked, and the rocks drifted apart) (Matthew 27:51), and Handel’s Messiah at the text “I will shake the heavens and the earth, the sea and the dry land” (Haggai 2:6–7). In the oratorio Der Tod Jesu by Heinrich Graun (1755), the figure was used in both senses: the heart pulsating during the Gethsemane prayer (“You tremble like a sinner who hears the sentence of death”) and the trembling of the earth during the Golgotha earthquake (“Tremble, Golgotha, He died on your summit!”).

10. Andrushkevich, Lyzhov, and Serbin, liner notes, Ballets sans paroles.

11. The Bebung figures begin with the horns in Example 16.4a and culminate in the Chorus on the words “I am the first—He saith—and the last. And the thunder resoundingly answered” (see score).

12. Literally “ascension,” a fixed term in Baroque Figurenlehre. On semantics and sources, see, for example, “Anabasis, Ascensus: an ascending musical figure which expresses ascending or exalted images or affections,” in Bartel, Musica Poetica, 439. Specifically on anabasis and its Baroque sources, see ibid., 179.

13. “Saltus Duriusculus: a dissonant leap” (ibid., 443); on sources, see ibid., 381.

14. “Tremolo, Trillo: (1) an instrumental or vocal trembling on one note” (ibid., 443).

15. Literally, “cutting”: “Tmesis, Sectio: a sudden interruption or fragmentation of the melody through rests” (ibid., 447); on sources, see ibid., 412–13.

16. “Passus duriusculus: a chromatically altered ascending or descending melodic line” (ibid., 357).

17. Stravinskii to Nikolai Rerikh, 21 February / 6 March 1912, in Varunts, I. F. Stravinskii, 1:314.

18. Stravinskii to Nikolai Findeizen, 2/15 December 1912, in Varunts, I. F. Stravinskii, 1:387.

19. The use of the adjective “lapidary” referring to the rhythm in Russian is as unusual as it may seem in English. In Russian this term means “engraved on stone” but also “laconic, concise,” and “hammered.” Those additional characteristics were probably important for Stravinsky in this context.

20. Remarkably, the concept of “fate” or “doom,” entirely lacking in Roerich’s presentation of the ballet, is highly relevant for Stravinsky’s descriptions of The Rite’s scenario. Thus, in a letter to Findeizen, he writes, “In the second part, the maidens conduct mystic games on a sacred hill at night. One of the maidens is doomed to sacrifice”; see Stravinskii to Nikolai Findeizen, 2/15 December 1912, in Varunts, I. F. Stravinskii, 1:387. As late as February 1914, in the program notes for the concert performances of The Rite in Moscow and St. Petersburg, Stravinsky states, “Maidens conduct mystic night games, walking in circles. One of the maidens is doomed to sacrifice. Fate points to her twice”; see Stravinsky and Craft, Stravinsky in Pictures and Documents, 78. In Rameau’s Hippolyte et Aricie, it is the journey of Theseus to the Underworld on behalf of his friend, the invocation of gods Neptune and Pluto, and the verdict of the Fates; in The Rite it is the “Evocation of the Ancestors” and the “Glorification of the Chosen One.”