Stravinsky’s epochal Le sacre du printemps premiered in Paris on 29 May 1913. Its fiftieth anniversary in 1963 was marked by, among other things, a recording of the piece by the London Festival Orchestra for the series Music of the World’s Great Composers, conducted by René Leibowitz.1 The recording is curious and intriguing for many reasons, not least because Leibowitz—as both composer and conductor—was a deeply devoted Schoenbergian who made the recording when twelve-tone thought was vital to contemporary composition. The LP, reissued by Chesky as a compact disc in 1990, is also remarkable in that it likely constitutes the only audio documentation of a connection between Schoenberg’s artistic credo and the phenomenon that was Le sacre. Convinced as Leibowitz was of Schoenberg’s outlook on musical performance as both reformulated and expressed by the composer’s student and brother-in-law, the violinist Rudolf Kolisch, he thus contrived—however recklessly—to apply Austro-German musical principles to Stravinsky’s essentially Russian music.

This essay will begin by focusing on Schoenberg’s lifelong admiration of Stravinsky’s early works despite the theoretical and aesthetic beliefs that pushed him into opposition with Stravinsky in the 1920s. Leibowitz espoused both Schoenberg’s positive and negative thoughts toward Stravinsky. Moreover, in adopting the Schoenberg-Kolisch tenets for performance, he interpreted Le sacre with a Schoenbergian analysis in his mind’s ear. I shall offer such an analysis of the Introduction to Part I as a case study of the insights it offers into the piece. Inevitably, such an analysis and Leibowitz’s enactment of it consider what, for Schoenberg, was Le sacre’s overall lack of organic presentation through developing variation.2 Schoenberg would have deplored this fact, even while holding Stravinsky’s orchestration in high regard.

STRAVINSKY PERFORMANCES AT THE VEREIN

IN VIENNA:

8, 9, and 17 February 1919; 20 September 1920

Three Easy Pieces for piano four-hands

Five Easy Pieces for piano four-hands

6 June 1919

Berceuses de chat for voice and three clarinets

Pribaoutki for voice and eight instruments

13 October 1920+

Pétrouchka for piano four-hands

2 June 1920

Piano-Rag Music

Three Pieces for String Quartet*

IN PRAGUE:

CANCELED 14 March 1920

Three Pieces for String Quartet*

26 May 1922

Piano-Rag Music

+For the advertisement of the concert, see T.84.01, Mitteilung No. 20/1, Arnold Schönberg Center, Vienna.

*The piece was advertised as being performed on 2 June 1920 in Vienna (see T84.01, Mitteilung No. 15/1, Arnold Schönberg Center, Vienna), and then on 14 March in Prague. Because programs were never given out at Verein concerts, only Stravinsky’s later comment confirms that neither the Vienna nor the Prague performance took place (see Stravinsky and Craft, Stravinsky in Pictures and Documents, 637).

Figure 20.1. Performances of Stravinsky’s music at Schoenberg’s Verein für musikalische Privataufführungen (Society for the Private Performance of Music).

From 1912 to 1919 Schoenberg and Stravinsky were, in the pianist Leonard Stein’s words, “on good terms.”3 Stravinsky was clearly impressed by Pierrot lunaire; Schoenberg admired Petrushka. Indeed, even in 1926, during the heyday of the Schoenberg-Stravinsky polemics, he could write: “I really liked Petrushka. Parts of it very much indeed.”4 Schoenberg’s surviving library contains a score of the piece—its well-creased, discolored bottom-right-hand corners show that he had read it frequently.5 Since Schoenberg’s own handwritten catalog of his books and music indicates that he acquired the score before 1915, it is even possible that Stravinsky and/or Sergei Diaghilev could have given it to him at the work’s Berlin premiere. Schoenberg did not subsequently attend the Viennese premiere of Petrushka on 15 January 1913, nor did he have sufficient funds to attend the Paris premiere of his own “Lied der Waldtaube” (Song of the wood dove) from Gurrelieder on 22 June 1913, performed on the same program as the Introduction to Part II of Le sacre in the version for two pianos.6

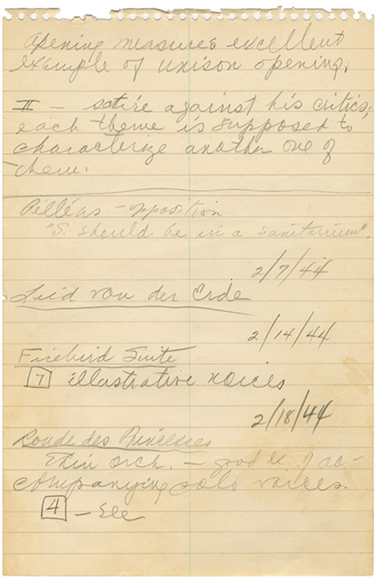

Figure 20.2. Page from Clara Steuermann’s class notes from the University of California at Los Angeles mentioning The Firebird (dated 14 and 18 February 1944).

Clara Steuermann Satellite Collection, S25, F21, Arnold Schönberg Center, Vienna.

Transcription:

2/14/44

Firebird Suite

[rehearsal no.] 7 illustrative voices

2/18/44

Ronde des princesses[,]

Thin orch[estration].—good ex. of accompanying solo voices

[rehearsal no.] 4—see

Printed with the kind permission of Lawrence Schoenberg.

After World War I, from 1919 to 1922, Schoenberg’s Verein für musikalische Privataufführungen (Society for the Private Performance of Music) was virtually the only venue at which Stravinsky’s music could consistently be heard in Vienna and Prague (see Figure 20.1).7 The society performed six works of Stravinsky’s, including Pribaoutki and the four-hand arrangement of Petrushka.8 To Stravinsky’s consternation, the intended performance of Trois pièces pour quatuor à cordes (Three Pieces for String Quartet) never took place.9 All the scores of these works (except the last) remain in Schoenberg’s library at the Arnold Schönberg Center in Vienna; most contain annotations for performance, but they have no analytic markings to suggest that he studied them in detail.10

His lifelong friend and interpreter, the pianist Eduard Steuermann, remembers that Schoenberg was impressed by the orchestration of Pribaoutki.11 He understood it as an integral part of the work’s compositional presentation.12 Moreover, decades later, Clara Steuermann’s and Warren Langlie’s class notes from Schoenberg’s 1944 orchestration course at the University of California at Los Angeles document his teaching of The Firebird, in which he praised Stravinsky’s skill in relating instrumentation to the interaction of polyphonic lines (see Figure 20.2).13 In 1949 Schoenberg demonstrated his admiration for such orchestration by showing his plan to include the same number of extracts (thirty-six) of his own music and Stravinsky’s in his orchestration textbook, each constituting 8 percent of those in the book (see Figure 20.3).

Figure 20.3. List of composers to be included in Schoenberg’s proposed orchestration textbook “Materials for Orchestration.” Typescript, T68.13, folder 18, Arnold Schönberg Center, Vienna. Printed with the kind permission of Lawrence Schoenberg.

Figure 20.4. The first page of Schoenberg’s copy of Le sacre with folded corner (Berlin: Édition Russe de Musique / Breitkopf und Härtel, 1921). MSCO S20, Arnold Schönberg Center. Printed with the kind permission of Lawrence Schoenberg. The Rite of Spring by Igor Stravinsky © Copyright 1912, 1921 by Hawkes & Son (London) Ltd. Reprinted by permission of Boosey & Hawkes, Inc.

Schoenberg acquired scores of Le sacre and Le rossignol soon after their publication in the early 1920s and bound them together (he was an accomplished bookbinder). The Sacre score is devoid of annotation, but the deeply creased corners of each page evince considerable study of the piece (see Figure 20.4). Around the time Schoenberg obtained the scores, the composer Darius Milhaud had arranged premieres in Paris of Pierrot lunaire, op. 12 (16 January 1922), the String Quartet No. 2, op. 10, and Herzgewächse (Foliage of the heart), op. 20 (30 March 1922) and performances of the Fünf Orchesterstücke (Five Pieces for Orchestra), op. 16, and the Kammersymphonie, Nr. 1 (Chamber Symphony No. 1), op. 9 (23 April 1922).14 After hearing the January premiere of Pierrot, Léonide Massine, who had choreographed Le sacre and Pulcinella two years before, approached Schoenberg through Milhaud and composer-musicologist Egon Wellesz, offering to choreograph his work as a ballet, but Schoenberg was not receptive to the project.15

From 1920 to 1925, French artistic circles and the press alike were hotly debating the compositional value of Austro-German atonality versus Franco-Russian polytonality, while Schoenberg’s negative evaluations of Stravinsky and his music were becoming more frequent.16 From 1922 to 1924, he wrote a number of unpublished fragments distinguishing his values and thought from those of Stravinsky and the Franco-Russian school.17 In an oft-quoted passage from a manuscript entitled “Polytonalists,” Schoenberg questioned the ability of Stravinsky, Alfredo Casella, Milhaud, and Béla Bartók to structure coherent and organic forms from a basic configuration, or Grundgestalt.18 He writes: “They almost without exception lay down themes which in their germinal state demonstrate no need to be handled in the manner in which they should be; . . . my contemporaries’ music makes golden watches out of iron, rubber tires out of wood and the like—thus, [their music] doesn’t do justice to its material.”19

As early as 1922, Schoenberg frowned on the use of literal pitch repetition, ostinati, and juxtaposition of materials: “The method: keep repeating a figure long enough until some change in the other voices happens to produce something ‘ingenious’—or until the repetition itself becomes ‘comic.’ . . . Yes, one almost laughs at such things every time—but with less and less empathy . . . rather, with more and more discomfort—confirming one’s feeling to the point of nausea.”20

After the premiere of Stravinsky’s Octet in 1923, the press in France and Germany extolled him as a “new Bach.”21 Envious, Schoenberg tried to relieve his frustration in the unpublished fragment “Polytonality and Me,” a private response to an article by Casella, who had deemed Le sacre the source of polytonal techniques.22 By obsessively finding contrapuntal parts read simultaneously in diferent keys in works he had composed before Le sacre, Schoenberg asserted, “I am not only to blame for atonal music, but at least partially accountable for polytonal music as well” (compare Figure 20.5).23 He ignored the crucial fact that his work’s “polytonality” existed only in a chromatic, Wagnerian context foreign to Le sacre. A year later, in 1925, he would compose the third movement of Drei Satiren (Three Satires), op. 28, in which he would return to the issue of polytonality, this time with a twelve-tone row containing combinations of triads.24

Figure 20.5. A text excerpt from Schoenberg’s “Polytonality and Me” with its illustration in Pelleas und Melisande, op. 5, R-8:1–5. Typescript, T04.11, Arnold Schönberg Center, Vienna. Copyright 1912 by Universal Edition, A.G., Wien. Copyright renewed 1939.

Three years after Schoenberg composed Drei Satiren, in 1928, the Warsaw-born/Berlin-raised teenager René Leibowitz would move to Paris from Berlin. His early biography is difficult to ascertain, but Leibowitz’s role as a champion of the Second Viennese School clearly began in 1936, when he met both of his mentors, Kolisch and the German composer-pianist Erich Itor Kahn, at a Kolisch Quartet concert in Paris.25

From 1929 to 1933, Kahn performed Schoenberg’s piano works on Frankfurt Radio broadcasts while he was an assistant to the conductor Hans Rosbaud, a supporter of the composer. Kahn also composed his own highly contrapuntal twelve-tone music.26 Like Kolisch and Rosbaud, he had a personal relationship with Schoenberg, who specifically requested that Kahn play the musical examples for his lecture on the Variations for Orchestra, op. 31, broadcast from Frankfurt on 31 March 1931. However, Kahn was also the regular accompanist of the violinist Samuel Dushkin, who introduced him to Stravinsky. In 1936 Stravinsky asked Kahn to create the piano reduction of Jeu de cartes. In 1937 Karl Böhm conducted the European premiere in Dresden with the support of the Nazi Party; consequently, Stravinsky did not credit Kahn, a Jew, in the published score.27

Leibowitz’s study with Kahn centered on both Schoenberg’s tonal and twelve-tone theories.28 Their student-teacher relationship lasted from 1937 until early 1939, when Kahn was interned at the French internment camp Camp des Milles in Aix-en-Provence. During his captivity, he wrote the second of his Six Bagatelles for Piano (1935–42), dedicated to Leibowitz. When Kahn and his wife, Frida, were finally able to flee to New York in 1941, they asked Leibowitz to safeguard Kahn’s own musical manuscripts, which had to be left behind. During the war, Leibowitz studied these scores either in hiding at Saint Tropez or in respites from working for the Resistance.29 Fifteen years later, in 1957, Leibowitz (with the pianist-musicologist Konrad Wolff) would write a laudatory book about his mentor, commenting especially on his twelve-tone works.30

During the time of Leibowitz’s final face-to-face lessons with Kahn, in March 1938, the Kolisch Quartet returned to Europe for a tour; because of the Anschluss in Austria, they spent three weeks based in Paris. Kolisch met then with Kahn and Leibowitz to discuss his notions of performance practice, especially his beliefs about tempo in Beethoven’s music.31 Leibowitz was captivated by Kolisch’s thoughts. Kolisch, like Schoenberg, believed that the first task of a performer was to convey the work’s “idea,” a meaningful expression of life’s truths, and such a notion of the idea’s presentation rested on principles of an order higher than style. As a result, Kolisch’s own performance of Bartók’s Sonata for Violin with the composer as pianist,32 or his 1940 performance of Stravinsky’s Suite from Histoire du soldat, would have received the same preparatory treatment as that given a work of Beethoven or Schoenberg, thus prefiguring Leibowitz’s application of Austro-German performance practice to Le sacre.33

Figure 20.6. René Leibowitz and Rudolf Kolisch (ca. 1948). René Leibowitz Collection, Paul Sacher Foundation, Basel.

Kolisch held that performers should prepare a work through conscious analysis, using exclusively Schoenbergian methods. Once a work was thoroughly scrutinized, the performer would engage in multiple silent hearings of it that would discourage any attempts at purely mechanical interpretation or self-indulgent virtuosity.34 Silent study was meant to imbue the work with an originality of interpretation—for Kolisch, listening to recordings by others in preparation for his own future performance was a waste of time. Moreover, a purely imagined version of a piece assured the internalization of the score’s “objective” elements (minutely measurable and realized from the notation) and those that were “espressivo” (the “speech-like” elements of inflection, articulation, and accentuation), also derived from conscious analysis. And indeed, Kolisch’s ideas concur with Schoenberg’s statement: “A musician is a man who, when he sees music, hears something in his mind. And an instrumentalist is one who can play what he has in his mind.”35

Lowell Creitz, the cellist of the Pro Arte Quartet (of which Kolisch was first violinist), explained that Kolisch followed very specific preparatory procedures for establishing a work’s tempo. Once quartet members had engaged in intensive analysis and internal hearings of the score at different speeds on their own and then had had discussions about it, they would play the motives of the opening theme, or Grundgestalt, at a variety of speeds. They did so with the aim of digesting the work’s material and with the intention of choosing one tempo that they believed would relay to an audience the clearest statement of the work’s coherent components, those that would best convey to the listeners a work’s deeper meaning.36

Clearly, for Kolisch, tempo was a primary—if not the primary—concern in expressing the thought of a work. In his influential 1943 article “Tempo and Character in Beethoven’s Music”—strongly praised by Schoenberg—Kolisch argued that it was wrong to dismiss the then-infamous metronome markings in Beethoven’s symphonies as too fast and sometimes unplayable.37 In the late 1950s and early 1960s, when he was about to record Le sacre, Leibowitz, under Kolisch’s watchful eye and ear, successfully made the first recording of the complete Beethoven symphonies following the tempi and inherent characters indicated by the original markings.38 Kolisch termed performances such as the Leibowitz recordings “re-creative” acts; and, indeed, Leibowitz echoed Kolisch by asserting, “Performance is the re-creation of a work.”39 (See Figure 20.6 for a photograph of Leibowitz and Kolisch.)

Unlike Kolisch, Leibowitz valued subversion, and in many ways, his fiftieth-birthday recording of Le sacre, made in 1960 and released in 1963, is a subversive act.40 Leibowitz often repeated that virtually all works of Stravinsky were compositionally flawed for many of the same reasons proposed by Schoenberg in the 1920s. Leibowitz wrote: “A sometimes brilliant musician like Igor Strawinsky has never been able to pull himself up to the level of the really great masters, because the (sometimes grandiose) structures he invents are hardly ever linked together in an organic way.”41

Leibowitz specifically writes of Le sacre: “Even in his boldest works, the segments, themes, sections are simply juxtaposed rather than organically developed. Although I doubt if anything really valuable can be achieved this way, one must admit Stravinsky’s skill and lucidity. . . . [These qualities] constitute an assault against musical composition as such, a radical questioning of traditional means.”42 Thus Leibowitz would aspire to create an original reading of Le sacre, one that would try to minimalize its compositional shortcomings even while conveying the work’s appealing radicalism. Portions of the Introduction to Part I of Le sacre can serve as a case study of Leibowitz’s singular approach: they encapsulate issues that arise again throughout his performance.

Like Kolisch, Leibowitz believed that tempo was the central component of a work’s interpretation. Its treatment should never feed a self-indulgent, cheap virtuosity that would please the crowd—and such cheap virtuosity was a danger in a work such as Le sacre, known in its early life for its virtuosic parts. Leibowitz focused on the interpretation of the score’s tempo shift in R-3:1–2 from ♩ = 50 to ♩ = 66 (see Figure 20.7). The original tempo of ♩ = 50 only returns again at R-12:1 with the reappearance of the main bassoon theme. Within the time span from R-3:1 to R-12:1, there are virtually no cadence points or tempo changes indicated in the score to parse the work into traditional formal sections. However, the Kolisch-Schoenberg approach assumed that, like any well-crafted Austro-German composition, Le sacre would have periodic cadences and functioning phrases.

Figure 20.7. Stravinsky’s and Leibowitz’s tempi in sections of Le sacre’s Introduction, Part I.

Leibowitz decided to “improve” Stravinsky’s score. At the work’s opening, he assumed the pace of Stravinsky’s 1960 recording (♩ = 48), and he presented R-3:1 as a cadential gesture punctuated with a typical Austro-German ritard; in R-3:2 he returned to the original tempo, ignoring Stravinsky’s indication of più mosso (see Figure 20.7 and Example 20.1; Audio Clip 20.1 for Example 20.1, from the beginning of The Rite to R-12:4, also includes sound clips for Examples 20.2, 20.3a–d, 20.4, and 20.5a–f).43 The slower tempo makes the lines articulative and clear, if less virtuosic.44 Moreover, he conceived the melody in R-6:5–10 as analogous to that of mm. 1–3 and made a cadence at R-6:10–11 with a very obvious rubato to a ritard; only at the upbeat to R-7:1 did he begin his più mosso at ♩ = 52, a tempo that continues until the return of the main theme at R-12:1 (see Example 20.2).45

Example 20.1. Leibowitz’s adjustments of tempi in R-3:1–2. The Rite of Spring by Igor Stravinsky © Copyright 1912, 1921 by Hawkes & Son (London) Ltd. Reprinted by permission of Boosey & Hawkes, Inc.

Example 20.2. Leibowitz’s adjustments of tempi in R-6:10–11 into R-7:1. (Example begins at R-6:4.) The Rite of Spring by Igor Stravinsky © Copyright 1912, 1921 by Hawkes & Son (London) Ltd. Reprinted by permission of Boosey & Hawkes, Inc.

Example 20.3a. The orchestration of stable and unstable characteristics of Theme 1. The Rite of Spring by Igor Stravinsky © Copyright 1912, 1921 by Hawkes & Son (London) Ltd. Reprinted by permission of Boosey & Hawkes, Inc.

Example 20.3b. The orchestration of stable and unstable characteristics of Theme 2. The Rite of Spring by Igor Stravinsky © Copyright 1912, 1921 by Hawkes & Son (London) Ltd. Reprinted by permission of Boosey & Hawkes, Inc.

As a devotee of Kolisch, Leibowitz would have based his interpretation as a whole on a highly detailed study of Le sacre using the Kolisch-Schoenberg methods for analyzing pitch relations; he discussed such procedures face-to-face with Schoenberg during his visit to Los Angeles in the autumn of 1948.46 In a Schoenbergian sense, the opening theme of Stravinsky’s Le sacre—a Grundgestalt—had to mold itself through stable and contradictory elements (see Example 20.3a). Indeed, the bassoon’s Theme 1 features oscillating minor thirds, C–A, and a cadence in A Aeolian, events that contribute to coherence and stability. However, the C♯ here in the horn contradicts the theme’s clear modal sense by creating a cross relation with its C♮. The unstable, juxtaposed nature of the horn’s C♯ is what Schoenberg would describe as an imbalance—a “problem” questioning the coherence otherwise presented. Thus the bassoon part has stable materials, the horn unstable ones—and Stravinsky’s orchestration differentiates their unique roles.47

At R-1:1 the bassoon begins a variant of its opening melody, reiterating the stable pitch relation of C–A; however, the clarinets add D♭ (enharmonic to the C♯ of m. 2) to the mix, along with A♭, and their chromatic descent establishes Theme 2 (see Example 20.3b). D♭ forms a major seventh with the upper line, D♭ against C, and A♭ forms a cross relation with the pitch A on the downbeat of R-1:2. Thus the bassoon’s C–A recalls the inherent stability of Theme 1, whereas the clarinets present the pitch components contradicting it.

After another repetition of the opening in the bassoon (R-1:2), Theme 3 makes a dramatic entrance in the English horn on the continually menacing pitch C♯, which now ascends a fourth to F♯ (see Example 20.3c); meanwhile, the fourth G♯ G♯ + C♯ sounds in the A clarinets and bass clarinets below. The low G♯ forms a minor ninth with the only stabilizing element here, the pedal tone A, continuing from the previous phrase and sustained until Theme 1 returns at R-3 (see Example 20.3d). Here, for the first time, the menacing C♯ (D♭ in R-3:1) leads to the stable C♮, as the G♯ descends to G♮. This cadential event is highlighted by orchestration, as C and G are heard for the first time in the bass clarinets, not the bassoon.

Any analysis using Schoenbergian principles clearly emphasizes the essential dialogue between stable and unstable components. However, in Stravinsky’s early music, the very essence of this instability derives from the juxtaposition of lines and phrases—and indeed juxtaposition was precisely the musical factor Schoenberg and Leibowitz abhorred. Thus, as the conductor, Leibowitz faced an interpretive dilemma: Should he highlight the juxtaposition of the stable and unstable components, or should he downplay their relationship and stress the coherent and stable repetitions of A and C in the bassoon line instead? Leibowitz ultimately chose to “improve” Le sacre by stressing coherence (see Example 20.4). In so doing, he dynamically emphasized the bassoon line as a melody with accompaniment and especially highlighted its Cs between m. 1 and R-3 and the sustained pedal tone A in R-2:1–2. As a result, C or A is prominent throughout the entire opening section, as is the minor third, the interval shared by all of the main themes.

Example 20.3c. The orchestration of stable and unstable characteristics of Theme 3. The Rite of Spring by Igor Stravinsky © Copyright 1912, 1921 by Hawkes & Son (London) Ltd. Reprinted by permission of Boosey & Hawkes, Inc.

Example 20.3d. The orchestration of stable characteristics of Theme 1’s cadence. The Rite of Spring by Igor Stravinsky © Copyright 1912, 1921 by Hawkes & Son (London) Ltd. Reprinted by permission of Boosey & Hawkes, Inc.

Example 20.4 Emphasis of the bassoon and its pitches A–C in Leibowitz’s performance. The Rite of Spring by Igor Stravinsky © Copyright 1912, 1921 by Hawkes & Son (London) Ltd. Reprinted by permission of Boosey & Hawkes, Inc.

Figure 20.8. Themes 1–3 and their orchestration.

Leibowitz’s analytically based approach to Le sacre calls attention to the themes in the bassoon, clarinets, and English horn at the opening.48 And indeed the orchestration of these themes has a structuring influence on the Introduction as a whole. Repeated or slightly altered versions of Theme 1 are only iterated in the bassoon, those of Theme 2 (the descending chromatic line) in the clarinets, and those of Theme 3 only in the oboe or English horn (see Figure 20.8).49 This timbral and thematic consistency can be traced across the Introduction and, ultimately, shapes its form.50 For example, the interval of the minor third in the opening bassoon line (e.g., C–A) extends in chain-like fashion to C–A–G♭(R-1:1–2) and descends to D♭–B♭–G–E in the A clarinet line (R-1:1–3); together these chromatically filled minor thirds form octatonic relations (see Example 20.5a–b). Subsequently the three entrances of Theme 2 in the clarinets (beginning at R-4:1, R-7:1, and R-10:1) also form octatonically related minor-third chains (see Example 20.5c–e). The final chain in the clarinets ends on B (see Example 20.5e), followed by the bassoon’s C♭–A♭ in the main theme (R-12:1, see Example 20.5f). In this sense, the descending minor-third themes articulate a coherent “long line” across the Introduction, one highlighted by Leibowitz in his performance.51

Is Leibowitz’s performance, with its slow, careful tempi, added ritards, and emphasis on coherent materials and structuring instrumentation, an illuminating way to hear the Introduction of Le sacre? On the one hand, his performance clearly impressed Pierre Boulez, who valued Leibowitz’s choice of tempi. In his renowned 1969 recording,52 Boulez copied (or closely approximated) Leibowitz’s tempi not only in the Introduction but also in many other sections throughout the performance—except for the slowest ones (see Figure 20.9). On the other hand, Leibowitz’s interpretation overall did not meet with critical acclaim when it was released on compact disc. For example, the California critic Jeffrey Lipscomb described the performance as “pretty analytical and slightly under-powered.”53 The British reviewer Christopher Howell commented, “[Leibowitz] was lukewarm about Stravinsky—and recorded a lukewarm performance of The Rite of Spring.”54 These critics seem to have been seeking the sort of faster, more visceral rendition to which audiences are now accustomed—not the slow, intellectually reasoned, contrapuntally clear, cohesive, Kolisch-approved Le sacre of Leibowitz.

This spread, Example 20.5. Octatonic relations of minor thirds in ongoing themes of the clarinets and bassoon. The Rite of Spring by Igor Stravinsky © Copyright 1912, 1921 by Hawkes & Son (London) Ltd. Reprinted by permission of Boosey & Hawkes, Inc.

Figure 20.9. Tempi of Leibowitz’s recording and Boulez’s 1969 recording. Boulez’s tempi are taken from Peter Hill, Stravinsky, 124. Arrows indicate tempi that are alike or closely related.

I have argued that Leibowitz’s reading is valuable in a historical sense. And indeed, perhaps it functions best as a performance when considered also as a document; as with the aforementioned manuscripts at the Schönberg Center, it addresses and comments on issues central to the Stravinsky-Schoenberg polemics of the 1920s. Moreover, a Schoenbergian analysis directs us to a renewed appreciation of Stravinsky’s technical proficiency, raising orchestration to a virtually unprecedented level of structural importance in compositional design. And it is this fact that is crucial not only in evaluating Leibowitz’s reading but also in assessing Schoenberg’s positive reception of Stravinsky’s early works. As we know from other extant manuscripts, it was Stravinsky’s structural orchestration that captivated Schoenberg, along with the whole world of music.

I thank the following persons for their invaluable help in the preparation of this essay: Rosalie Calabrese; Grant Chorley; Joel Feigin; Letitia Glozer; John Reef; and Therese Muxeneder and Eike Fess, archivists at the Arnold Schönberg Center, Vienna, Austria. I further thank Nuria Schoenberg Nono, Lawrence Schoenberg, and Ronald Schoenberg for their kind permission to print their father’s documents related to the topics of this essay.

1. Stravinsky, The Rite of Spring, with the London Festival Orchestra; Igor Stravinsky, Petrouchka / Le sacre du printemps, with the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra.

2. For an explanation of “developing variation,” see Schoenberg, The Musical Idea, 365–66.

3. Stein, “Schoenberg and ‘Kleine Modernsky,’” 313.

4. Schoenberg, Style and Idea, 483.

5. Score MSCO S48, Arnold Schönberg Center, Vienna.

6. The Société des Grandes Auditions Musicales, under the leadership of Élisabeth, comtesse Greffulhe, sponsored the concert. In his review, the musicologist-critic Henri Quittard, a student of César Franck, wrote the following about the performance of “Song of the Wood Dove”: “We have heard an excerpt from Monsieur Arnold Schönberg’s Gurre-Lieder; he is an Austrian—but not a revolutionary; he has a feeling for expression; his harmonies have color and accentuation; declamation is correctly rendered. In Maria [sic] Freund he has found a magnificent interpreter; her beautiful voice, as well as her precise and unmannered declamation contributed much to the composer’s success.” He was unimpressed with Le sacre: “Monsieur Stravinsky’s Le sacre du printemps was somewhat surprising, I must say; I found its merits no more appealing in the concert hall than I had in the theater” (Quittard, “Société des grandes auditions musicales,” translations by Grant Chorley). For further reviews, see the letter of Marya Freund to Arnold Schoenberg, 23 June 1923, Arnold Schoenberg Collection, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.

7. Compare Meibach, “Schoenberg’s ‘Society for Musical Private Performances,’” 247, 251, 257, 260–61, 270.

8. Webern commented favorably on Stravinsky’s compositions: “The cradle songs are something so indescribably touching. How those three clarinets sound! And ‘Pribaoutki’! Ah, my dear friend, it is something really glorious. This reality (realism) leads into the metaphysical” (Moldenhauer, Anton von Webern, 229). For Berg’s remarks, which are similar, see Brand, Hailey, and Harris, The Berg–Schoenberg Correspondence, 291, 304.

9. Stravinsky and Craft, Stravinsky in Pictures and Documents, 637; compare Stravinsky’s letter to Arnold Schoenberg, 27 May 1919, Arnold Schoenberg Collection, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.

10. See the scores numbered MSCO 928–40 at the Arnold Schönberg Center, Vienna.

11. Steuermann writes: “Schoenberg was rather interested in Stravinsky; he found his instrumentation very clever. We performed Pribaoutki, and Schoenberg said, ‘He always writes mezzo forte, and how well it sounds.’ (Schoenberg always advised his students never to write mezzo forte, but either forte or piano.)” (Steuermann, A Not Quite Innocent Bystander, 181). In turn, Stravinsky praised Schoenberg’s orchestration not only in Pierrot but also in his 1922 orchestral arrangements of two Bach chorale preludes, Schmücke dich, o liebe Seele (Adorn thyself, O beloved soul), BWV 654, and Komm, Gott, Schöpfer, heiliger Geist (Come, God, Creator, Holy Spirit), BWV 667; see Walsh, Stravinsky: A Creative Spring, 424.

12. In 1917 he asserted in his treatise on instrumentation: “The true basis of orchestration is composition itself. Therefore the student must first choose: what is the nature of a composition, so that may be suitable for this or that instrumental combination. Hence the most important requirement is to invent for the orchestra” (Schoenberg, Zusammenhang, 78–79).

13. The notes of Warren Langlie, Steuermann’s classmate, offer greater detail:

Stravinsky, Firebird Suite. I do not know this score at all. It is difficult. Such a score one has to study if he wants to know something about it. Ronde des princesses. The first reason for a change of organization would be structural, the second would be emotional, the third, for variety [emphasis in original]. The changes here appear to have been made for variety. See what a change of sound comes in measure 6 with the addition of such a few instruments. At “4”: a good example of soli accompanied by strings. The movement of the strings is good: the crossing of the two instruments, first and second violins.—to hear first from the right and then from the left. This is why the second violins should be on the right hand, not behind the first violin. The second violin part is good, for it makes a voice out of the movement. (Warren Langlie, class notes, 14 February 1944, Arnold Schönberg Center, Vienna)

14. For accounts of the Schoenberg performance in Paris, see the letter of Marya Freund to Arnold Schoenberg, 22 September 1922, Arnold Schoenberg Collection, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.; for a history of Schoenberg’s early career in France, see Mussat, “La réception de Schönberg en France,” 175–76.

15. Schoenberg wrote to Alma Mahler, who acted as a go-between between himself and Milhaud and Massine: “To perform ‘Pierrot’ without recitation but with dancing does strike me as going too far. I don’t think I’m being pedantic about it, even if I haven’t much more to say against this transcription than against any other. Anyway: I should have to do such a symphonic version myself, in order to conduct it myself. . . . But it isn’t a job I feel any enthusiasm for. I’d rather write Massine something new—even though not immediately” (Schoenberg, Arnold Schoenberg Letters, 69). See also the letter of Egon Wellesz to Arnold Schoenberg, 17 May 1922, Arnold Schönberg Center, Vienna.

16. For a summary of these commentaries, see Médicis, “Darius Milhaud and the Debate on Polytonality”; see also Milhaud, “Polytonality and Atonality” and “The Evolution of Modern Music.” Schoenberg’s negative feelings toward Stravinsky’s music arose earlier than the 1920s. In a state of pro-German, pre–World War I fervor, he sent a letter dated 28 August 1914 to Alma Mahler mentioning members and precursors of the Franco-Russian School: Georges Bizet, whom Stravinsky respected, as well as Stravinsky and his admirers Frederick Delius and Maurice Ravel. Schoenberg here stated his lifelong contempt for literal repetition in Franco-Russian music (e.g., ostinati) but expressed it by using curious arithmetic analogies. Ultimately, he said that their music was “infinity (ad infinitum)”—an infinite loop with the value of zero: “Now I know who the Frenchmen, English, Russians, Belgians, Americans, and Serbs are: Montenegrins! The music told me that a long time ago. I was surprised that not everyone felt as I did. I always thought Bizet + Stravinsky = Delius, and Delius ÷ Ravel = ∞ (ad infinitum), i.e., 0 ÷ 0 = ∞. A long time ago this music was a declaration of war, an attack on Germany” (Tenner, Alma Mahler–Arnold Schönberg, 85, translation by Grant Chorley). Schoenberg’s criticisms of 1923–24 remain nationalistic in tone; the use of arithmetic in the above quotation to describe non-German music implies that it is mechanistic, not organic.

17. The typescripts are “Ostinato,” T34.05, 13 May 1922; “Polytonalists,” T34.07, 21 April 1923; “Polytonalists,” T34.38, 29 November 1923; and “Polytonality and Me,” T04.11, 12 December 1924. They are housed at the Arnold Schönberg Center, Vienna. For a detailed description, consult Krones, Arnold Schönberg in seinen Schriften, 480, 484–85.

18. For a discussion of the term Grundgestalt, see Schoenberg, The Musical Idea, 353–56.

19. Schoenberg, “Polytonalists,” 21 April 1923, translation by Grant Chorley.

20. See Schoenberg, “Ostinato,” 13 May 1922, translation by Grant Chorley.

21. Messing, Neoclassicism in Music, 134–35.

22. Casella, “Tone Problems of Today,” 164.

23. Schoenberg had previously explained the use of the word “polytonal” (as well as “pantonal”) to describe music; see Theory of Harmony, 432. In 1920 Schoenberg discussed the same topic in an exchange with Berg; see Brand, Hailey, and Harris, The Berg–Schoenberg Correspondence, 299, 303.

24. For a discussion of the prose documents concerning the Satiren, see Stein, “Kleine Modernsky,” app. 2, 319–24.

25. Leibowitz fabricated events of his early life. For example, he claimed that he was a student of Schoenberg in Berlin in 1928, of Anton Webern in 1931–32, and of Ravel and Pierre Monteux (the first conductor of Le sacre) in 1933. However, there is a complete lack of hard evidence to support these claims. For interpretations of his early biography, see Wieland, “Gespräch mit Claude Helffer,” 270; Kapp, “Shades of the Double’s Original,” 4–5; Maguire, “René Leibowitz,” 6–10; Meine, Ein Zwölftöner in Paris, 23–41.

26. Other movements are dedicated to the American pianist Beveridge Webster and the conductor-composer Erich Schmid, a Schoenberg student. Certain of his works—the String Quartet (1954), for example—place twelve-tone relations in contexts associated with tonal music; in particular, Invention No. 6, Hommage à Ravel, uses a triadic twelve-tone row that creates sounds of Franco-Russian tonality. Kahn’s Ciaccona dei tempi de guerra for piano (1943) and Actus tragicus (1947) speak to his experiences during the war. Throughout his life he also composed vocal music—madrigals, lieder, and cabaret songs, as well as settings of French, German, and Hassidic folksongs.

27. See Evans, “Stravinsky’s Music in Hitler’s Germany,” 59; and Craft, “Assisting Stravinsky.” For a discussion of Stravinsky and anti-Semitism, see Taruskin, Defining Russia Musically, 454–60.

28. Leibowitz claimed also to have taught himself twelve-tone technique from Felix Greissle’s preface in the pocket score of Schoenberg’s Wind Quintet, op. 26; see Kapp, “Shades of the Double’s Original,” 4; and Ogdon, “Series and Structure,” 232.

29. Compare Kahn, Generation in Turmoil, 199; for 1937–39 correspondence between Kahn and Leibowitz, see Allende-Blin, “Erich Itor Kahn.”

30. Leibowitz and Wolff, Erich Itor Kahn. The American twelve-tone composer Milton Babbitt reviewed the text with enthusiasm, largely because of his high respect for Kahn not only as a performer but also as a composer; see Babbitt, review of Erich Itor Kahn.

31. Compare Leibowitz and Wolff, Erich Itor Kahn, 104: “Shortly before the war, our friend Rudolf Kolisch revealed to Kahn and the author of these lines his intention to write an important essay on the interdependence of tempo and the agogic indications in movements of Beethoven. . . . We were deeply impressed by our friend’s ideas, and we heartily encouraged him to write his essay, which he duly completed; it was published a few years later. Its importance is considerable, and its influence was great” (translation by Grant Chorley).

32. Lowell Creitz wrote that “Kolisch and Bartók played together several times, presenting the music of Bartók in addition to the traditional repertoire.” It is unclear whether they played both of Bartók’s violin sonatas or just one of them (Creitz, “Rudolf Kolisch,” 171).

33. An entry on page 22 of the New York Times for 26 December 1940, “New School Group Heard: Rudolf Kolisch Directs Chamber Orchestra at Sixth Concert,” reads as follows: “Rudolf Kolisch will lead the New School Chamber Orchestra in the sixth concert tonight in Beethoven’s Septet, Op. 20, Stravinsky’s ‘Histoire d’un Soldat’ [sic] Suite and Wagner’s ‘Siegfried Idyll.’” Earlier, as first violinist of the Vienna Quartet in its 1926–28 seasons, he played Stravinsky’s Three Pieces for String Quartet. I thank Professor Derek Katz, University of California at Santa Barbara, for this latter information. See also Creitz, “Rudolf Kolisch,” 168.

34. For Kolisch’s ideas in his own words, see his “Musical Performance.” Moreover, Kolisch believed that if a performer had silently heard the salient features of the score in his or her mind, whole repetitions of the work would not be necessary in rehearsal, and thus the performance would retain a certain quality of freshness; see Satz, “Rudolf Kolisch in Boston,” 205. For discussion of the philosophical/aesthetic issues related to the Kolisch method, see Trippett, “Rudolf Kolisch,” 229–31.

35. Schoenberg, “What Is Musicianship?”

36. See Creitz, “Rudolf Kolisch,” 162–69 passim.

37. Kolisch, “Tempo and Character in Beethoven’s Music”; see also Schoenberg’s letter to Kolisch, 2 December 1943, Rudolf Kolisch Collection, Houghton Library, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA.

38. Beethoven, The Complete Symphonies, with the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra and the Beecham Choral Society. See also Leibowitz’s analogous discussion of tempo in Stravinsky’s Concerto in D: Le compositeur et son double, 97–110. The Beethoven recording was in the same series as Le sacre.

39. Leibowitz, Schoenberg and His School, xxiii; compare Kolisch, “The String Quartets of Beethoven,” 220.

40. Leibowitz writes, “The composer is necessarily subversive [emphasis in original]. In this continual subversion, in this [there is] always renewed revolt” (“The Musician’s Commitment,” 683). Leibowitz’s tendency to subversion was also present in interpretations. For example, in his recording of Schoenberg’s Ode to Napoleon, op. 42, he ignored the bass clef in the reciter’s part indicating a male voice. He used an actress, Ellen Adler, his partner in the late 1940s and the daughter of the renowned actress and acting teacher Stella Adler, instead.

41. Leibowitz, “Traité de la composition avec douze sons,” 27.

42. Leibowitz, “Schönberg and Stravinsky,” 362–63.

43. Leibowitz made many such “improvements” of tempo throughout his performance. He often added a ritard before thematic entrances (e.g., before the D♭–B♭–E♭–B♭ ostinato at R-12:6–10 and R-22:1–2, and the più mosso at R-92:3–4). He also changed tempi of whole sections: for example, he altered the opening of “Spring Rounds” (R-48:1) from the score’s ♩ = 108 to ♩ = 66, a tempo closer to the subsequent section (R-49:1). The lack of a shift in tempo undercuts Stravinsky’s intended juxtaposition between R-48 and R-49 and instead forms the “long line” associated with the Austro-German aesthetic.

44. Interestingly, Leibowitz’s famous student and nemesis, Pierre Boulez, would copy Leibowitz’s tempi for the Introduction in his 1969 recording of Le sacre; see tempi in Hill, Stravinsky, 124. However, completely beholden to the score, Boulez did not change the tempo at the indicated più mosso at R-3:2. For a general discussion of the Leibowitz-Boulez relationship, see Kapp, “Shades of the Double’s Original,” 2–16. The following examples show that Leibowitz consistently employed slower tempi than those indicated in the score, giving a contrapuntal character to the interaction of parts: “Games of the Rival Tribes,” ♩ = 132; “Procession of the Oldest and Wisest One,” ♩ = 132 and ♪(!) = 69; “Dance of the Earth,” ♩ = 136; “Mystic Circles,” ♩ = 56; and the “Glorification of the Chosen One,” ♪ + ♪ = 126. However, the “Sacrificial Dance” begins slowly at ♩ = 112 but moves to ♩ = 138, a tempo faster than that indicated by the score, setting up a Wilhelm Furtwängler–like acceleration to the final cadence.

45. The A–C/B–D of the melody beginning at R-6:4 (the first measure in Example 20.2) clearly refers to the same melodic contour in the opening bassoon line (m. 2). Leibowitz also adds a ritard to the end of bassoon theme in m. 3.

46. Leibowitz, “Traité de la composition”; see also Ogdon, “Concerning an Unpublished Treatise,” 36. For a study of the influence of Schoenberg’s theories on Leibowitz’s own compositions, see Neidhöfer and Schubert, “Form and Serial Function,” 3–5, 26. For a study of Schoenberg’s analytic methods, see Schoenberg, The Musical Idea, 60–73.

47. For a discussion of the implications of the C–C♯ in the ongoing iterations of major sevenths, see van den Toorn, The Music of Igor Stravinsky, 100 and Example 27. The C♯–D–C♯ returns as D♭–D–D♭ at an important moment in the narrative—when the Sage kisses the earth (R-71:2–4). This event marks its first appearance in the bassoon.

48. In Thinking for Orchestra, Leibowitz and Maguire specifically take note of the number of wind instruments in the opening phrase: “Except for measures 2 and 3 (where it is the second horn that accompanies the bassoon solo), the five clarinets constitute the accompaniments throughout this passage. Clarinet 1 and bass clarinet 2 play in measures 4, 5, 6 (the piccolo clarinet is added in measures 5 and 6) whereas clarinet 2 and bass clarinet 1 take over the characteristic motifs in fourths on the fermata in measure 6” (199–200).

49. However, variants of the themes appear in other instruments.

50. The use of structural orchestration is ongoing in Le sacre. For example, consider thematic/instrumental inter-referencing: the octatonic ostinato of the English horn in “Augurs of Spring” (R-14:1–4) recalls the same structure and instrumentation in the Introduction’s Theme 3 (R-3:2–8); the entrance of the strings at the opening of “Augurs” (R-13:1) recurs before the selection of “The Chosen One” (R-103:2); the flute theme at R-25:5–8 is prefigured in R-9:1. The use of instruments and themes also articulates both the musical and narrative form, for example, the ongoing tuba ostinato during the procession of the Sage extending from R-64:3 to R-78:6.

51. Leibowitz especially brings out the descending chromatic lines in the A clarinets and bass clarinets from R-10:1 through R-11:4.

52. Stravinsky, Le sacre du printemps / Petrushka, with the Cleveland Orchestra and the New York Philharmonic.

53. Lipscomb, customer review.

54. Howell, review of Jacques Offenbach, La belle Hélène.