He says that he has tried to continue the work in the older style, and that where differences are found they must be taken as the result of unconscious forces which are too strong for him.

“Stravinsky at Close Quarters,” Everyman, 1 May 1914

Soon after the first performance of Le sacre du printemps on 29 May 1913 at the Théâtre des Champs-Élysées in Paris, Stravinsky resumed work on Le rossignol (Solovei, or The Nightingale), an opera he had begun in 1908 and that was interrupted by his work on The Rite.1 In the year that followed, he completed Le rossignol, with the first performance taking place on 26 May 1914 at the Théâtre de l’Opéra in Paris.2

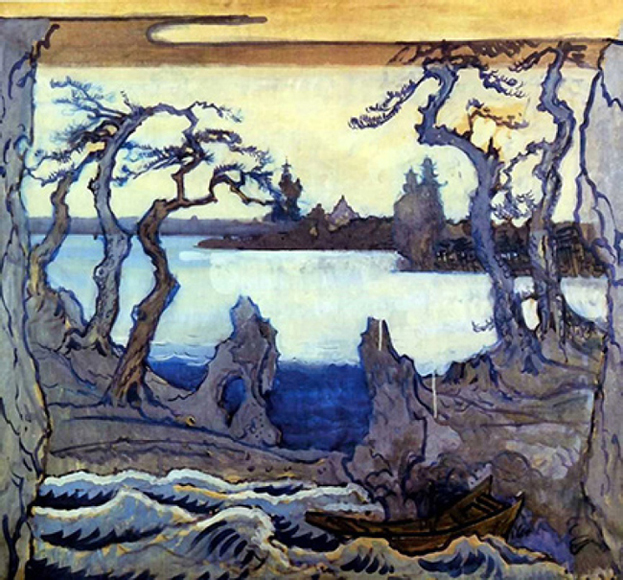

The production was designed by the art historian, critic, artist, and stage designer Alexandre Benois.3 Benois was a member of the Mir iskusstva, or World of Art, group around Diaghilev and a cofounder, with Diaghilev, Léon Bakst, and others, of the magazine of the same name.4 Among the productions he designed for the Ballets Russes were Le pavillon d’Armide (1909),5 Le festin (1909), Giselle (1910), Petrushka (1911), and Le rossignol.6 Figures 22.1–3 show the Benois sets for the opening production in Paris, while Figure 22.4 shows David Hockney’s set design for act 2 of Le rossignol (the Emperor’s Court) from the 2004 Metropolitan Opera production.

Figure 22.1. Alexandre Benois, set design for act 1 of Igor Stravinsky’s Le rossignol (Solovei, or The Nightingale), on 26 May 1914 at the Théâtre de l’Opéra in Paris, performed by Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes. This image depicts the Fisherman praying to the heavenly spirit and asking to hear the Nightingale sing. © 2014 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris.

Evidence that Stravinsky was mediating between the strident nature of The Rite and the mellifluous quality of The Nightingale is found in the definitive musical sketch for a scene at the end of act 2 of The Nightingale entitled “Jeu du rossignol mécanique” (Performance of the mechanical nightingale), where he wrote, “Очень доволен! [I am very satisfied!] 19 vii 1 viii 1913 [19 July / 1 August 1913],” and signed.7 We know that Stravinsky was in Ustilug at this time and that he was still somewhat depressed by the uproar over The Rite and convalescing from typhus.8 Nevertheless, his work on this sketch for the “Performance of the Mechanical Nightingale” must have brought him a high level of satisfaction because of the pleasure that he expressed upon its completion.

Figure 22.2. Benois, set design for act 2 of Le rossignol: the stage with lanterns, torches, and lights in preparation for the appearance of the Emperor. © 2014 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris. Photo credit: Snark / Art Resource, New York.

Figure 22.3. Benois, set design for act 3 of Le rossignol: the Emperor on his deathbed. © 2014 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris. WA1949.322 Alexandr Nikolavich Benois, “Design for the Decor of the Emperor’s Bedroom in Le Rossignol.” © Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford.

Figure 22.4. David Hockney, set design for act 2 of Le rossignol: the Emperor’s Court, from the 2004 Metropolitan Opera production (original production at the Metropolitan Opera on 3 December 1981 and two years later at the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, London). Photo by Erika Davidson, courtesy of The Metropolitan Opera Archives.

As indicated in the sketch (Figure 22.5) and the equivalent excerpt from the published score (R-92 up to R-94, Example 22.1, Audio Clip 22.1), the first two and one-third measures consist of the pitches C + E♭ + E♮. F♯.9 Beginning on the second beat of the third measure, two vertical sonorities consisting of C♯ + E♭ + B♭ and C♮ + E♮ are heard in alternation until the end of the scene.10 The lack of rhythmic differentiation among these repetitions suggests a feeling of rhythmic stasis, resulting in a block of octatonicism that serves as a backdrop for the pentatonic melody signifying the Mechanical Nightingale, written for the oboe.11 As a result, Stravinsky establishes an appropriate opposition between the Mechanical Nightingale and the Real Nightingale that was introduced earlier in act 1 of the opera, at R-18, a section composed before The Rite of Spring. Stravinsky accomplishes this dichotomy between the “Real” and the “Mechanical” by using repetitive pentatonic patterns for the Mechanical Nightingale, in contrast to the improvisatory chromatic patterns of the Real Nightingale. By means of his use of montage and textural layering in his depiction of the “Performance of the Mechanical Nightingale,” Stravinsky establishes rhythmic and harmonic stasis that helps to recall similar formulaic techniques in The Rite but with a more gentle outcome that satisfied Stravinsky, as he indicated on the sketch itself (Figure 22.5).

Figure 22.5. Igor Stravinsky, musical sketch for “Performance of the Mechanical Nightingale.” Igor Stravinsky Collection, Paul Sacher Foundation, Basel. The Nightingale by Igor Stravinsky © Copyright 1914 by Hawkes & Son (London) Ltd. Reprinted by permission of Boosey & Hawkes, Inc.

Example 22.1a–b. “Performance of the Mechanical Nightingale,” from Le rossignol, R-92 to R-94. The Nightingale by Igor Stravinsky © Copyright 1914 by Hawkes & Son (London) Ltd. Reprinted by permission of Boosey & Hawkes, Inc.

Example 22.2. Transcription of Stravinsky, sketch for Le rossignol, Introduction at R-5. Igor Stravinsky Collection, Paul Sacher Foundation, Basel. The Nightingale by Igor Stravinsky © Copyright 1914 by Hawkes & Son (London) Ltd. Reprinted by permission of Boosey & Hawkes, Inc.

Earlier in the opera, especially in his compositional process for the first act, Stravinsky had used repetitive patterns as well, but the result was different from that in the scene entitled “Performance of the Mechanical Nightingale.” In act 1 the patterns were often repeated sequentially and were more strongly influenced by paradigms that Stravinsky was likely to have learned from Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov or that he observed in one of Rimsky-Korsakov’s operas, but this was before The Rite. One example can be found in a short sketch that prefigures the end of the introductory material for act 1 (at R-5); this could have been written as early as 1908, before L’oiseau de feu (The Firebird) (1909–10).12

In this sketch (Example 22.2), Stravinsky wrote a melodic fragment that is accompanied by three layers, one of which outlines melodic tritones (line 2, starting on G♯) that slide down by half steps. The four-note pattern starting on the third line of the sketch can be reordered as D, E, F, G♯, which is repeated at the distance of interval class 5.13 This is a prominent collection of intervals that also signifies the Tsarevitch in The Firebird.14 The bottom line (4) outlines a descending chromatic scale.

The voice-leading paradigm in Example 22.3a (based on Example 22.2) shows how the sliding tritones of the upper voice can be thought of in relation to the descending chromatic line in the bass, resulting in sliding, nonfunctional, incomplete dominant seventh chords. This rhythmic reduction reflects Stravinsky’s compositional practice before The Rite, when he was strongly influenced by the harmonic principles he had learned from Rimsky-Korsakov. (Example 22.3b provides a piano reduction of the orchestral excerpt from which Example 22.3a is derived. See also Audio Clip 22.2.)

Example 22.3a. Voice-leading paradigm in Le rossignol, Introduction at R-5. The Nightingale by Igor Stravinsky © Copyright 1914 by Hawkes & Son (London) Ltd. Reprinted by permission of Boosey & Hawkes, Inc.

Example 22.3b. Le rossignol, Introduction at R-5. The Nightingale by Igor Stravinsky © Copyright 1914 by Hawkes & Son (London) Ltd. Reprinted by permission of Boosey & Hawkes, Inc.

The voice-leading paradigm that follows in Example 22.4a is based on an excerpt from Rimsky-Korsakov’s opera Kashchei bessmertnyi (Kashchei the deathless) starting at measure 107 of Tableau I.15 This passage could have served as a partial model for Stravinsky’s compositional process in the early stages of his sketching for The Nightingale.

Example 22.4a. Voice-leading paradigm in Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov, Kashchei bessmertnyi (Kashchei the deathless) at R-6 (see Example 22.4b).

A comparison between the voice-leading paradigm in Example 22.3a, from Stravinsky’s Nightingale, and the one in Example 22.4a, from Rimsky-Korsakov’s Kashchei the Deathless, shows similar structural features with regard to the sliding tritones and helps to explain how the compositional processes for both of these examples are related at the background rather than at the foreground level.16 In both of these reductions, the tritone governs the sequential repetition of symmetrical patterns. To clarify, in The Nightingale (Example 22.3a), the background structure is dominated by nonfunctional dominant seventh chords (with some enharmonic spellings) that slide down by half step, related to the interaction between the sliding tritones in the second line of the sketch and the chromatic bass line. In Kashchei the Deathless (Example 22.4a, the score of which is given in Example 22.4b), the formula is slightly different in that the structural harmony is a nonfunctional fully diminished seventh chord (F♯ + A + C + E♭). This background harmony occurs in three different positions: first with the F♯ in the upper voice, descending to the E♭, then to C, before the vocal line ends on A. As indicated in the voice-leading paradigm, the resulting harmonies overlap: a nonfunctional French augmented sixth chord that shares two pitches with a fully diminished seventh chord that is transposed down a minor third, generated by the sliding tritones that move down by half steps. Note that the resulting hexachord created by the melodic zigzag is important especially because it contains three successive tritones (E–B♭, E♭–A, and D–A♭ in Example 22.4a; and G♯–D, G♮–C♯, and F♯–C♮ in Example 22.3a). This technique also inspired Stravinsky’s approach to the “Carillon” section of The Firebird (from R-98 to R-101), where three different forms of this hexachord are used.17

Example 22.4b. Rimsky-Korsakov, Kashchei bessmertnyi at R-6. Available to listen on Spotify with Valery Gergiev conducting the Kirov Opera and Orchestra: http://open.spotify.com/track/5akJbFUQp2M2nmkuzgtSAT (accessed 1 March 2016).

The formulaic patterns discussed in Rimsky-Korsakov’s Kashchei the Deathless (Example 22.4a) and in the first act of Stravinsky’s Nightingale (Examples 22.2 and 22.3a) differ from Stravinsky’s musical depiction of the “Performance of the Mechanical Nightingale” in that Stravinsky appears to have abandoned the rigidity of the Korsakovian approach in favor of a more free-flowing style of pentatonic patterns in the melody line, accompanied by an octatonic block.18 Nevertheless, this resulting “block” in the “Performance of the Mechanical Nightingale” lacks the rhythmic differentiation that is characteristic of The Rite of Spring. Furthermore, the “Performance of the Mechanical Nightingale” appears only once in the opera, except for an allusion in the instrumental introduction to act 3. Therefore, it is difficult to discuss the function of this “sound block” in alternation with others, except to acknowledge that Stravinsky established contrast between the pentatonic nature of the melody signifying the Mechanical Nightingale and the chromatic nature of the melody signifying the Real Nightingale.

Because this definitive sketch was written so soon after The Rite of Spring and because it satisfied Stravinsky, it can be thought of as one of the composer’s first steps in his departure from the “older style” that characterized his work on Nightingale before The Rite. Stravinsky himself acknowledged the difference in style between the materials that he wrote before and after The Rite in the following interview:

“I’m very happy with the production of my opera,” said Igor Fedorovich in my conversation with him. . . . “The first act I wrote a few years ago, right after finishing the Firebird. The second and third acts were written this past winter. Because of that, the music might have suffered in coherence and unity of character, but, for various reasons, I did not want to change the first act, modifying it for the sake of the other two, just like I did not want to write the second and third acts completely in the spirit of the first.”19

In his “undated” review of the premiere in Paris (in La musique, 26 May 1914), Reynaldo Hahn captured the unique position of Le rossignol as having been written on both sides of The Rite: “One will feel/experience the spell of this strange and powerful music, this music that seems saturated/permeated with opium, glazed with precious lacquers [and], with an indefinable color and odor, situates the tale which it ornaments.”20 The delicate, exotic aura of Le rossignol, complemented by Benois’s stage designs, stands in stark contrast to the elemental, primitive aspects of The Rite, supported by Roerich’s heavy wool, leather, and fur costumes and Nijinsky’s new approach to choreography. Just as with the internal dichotomy between the “real” and “mechanical” nightingales, these two works, with their compositional overlap, speak to the dichotomies of style that characterize Stravinsky’s works for Diaghilev.

1. In his “Commentary to the Sketches,” page 13, written with Igor Stravinsky, Robert Craft explains that the presence of sketches for act 2 of The Nightingale, beginning on page 41 and extending through page 45 of the sketches for The Rite of Spring, is related to the change of date for the premiere performance of The Rite from 1912 to 1913. Pieter C. van den Toorn suggests that these particular sketches for The Nightingale were written in January 1912; see his Stravinsky and “The Rite of Spring,” 34.

2. This essay is excerpted from chapter 2 of my After the Rite.

3. Benois also worked briefly in film, heading the design team for Abel Gance’s 1927 Napoléon. See Garafola, “Dance, Film, and the Ballets Russes,” 23n29.

4. On the movement and its publications, see Kiselev, “Graphic Design and Russian Art Journals”; and Grover, “The World of Art Movement in Russia.”

5. This was a revised version of the production for which he had designed the staging and costumes to accompany Mikhail Fokine’s choreography at the Mariinsky Theater; see Bowlt, “Stage Design and the Ballets Russes,” 32. Benois also reworked Bakst’s costume designs from the Mariinsky production of Les sylphides when Diaghilev mounted a revised production in Paris in 1908; see the exhibition catalog edited by Pritchard, Diaghilev and the Ballets Russes, 78.

6. Bowlt, “Stage Design and the Ballets Russes,” 32–35.

7. In this instance, Stravinsky was accommodating the New Style and Old Style calendars.

8. “Depressed as he was by the debacle in Paris, and still in some measure convalescent from his typhoid, Igor could not take the rest he certainly needed when he got to Ustilug in the middle of July” (Walsh, A Creative Spring, 215).

9. Or pitch classes 0, 3, 4, 6, which can be thought of as the tetrachord 4–12 (0236).

10. Or pitch classes 1, 3, 10 and 0, 4, which can be thought of as the pentachord 5–10 (01346). In the published score, this scene begins at R-92 and lasts for eighteen measures. It is the only time that the Mechanical Nightingale appears in the opera except for allusions in act 3.

11. With regard to “rhythmic stasis,” see Taruskin, “‘ . . . la belle et saine barbarie,’” 25. In his discussion of the first movement of Three Pieces for String Quartet, Taruskin refers to “the frozen, rhythmic stasis” (die gefrorene rhythmische Bewegungslosigkeit) in the following way: “On the one hand it develops and broadens the ‘nepodvízhnost,’ that is accomplished in The Rite of Spring by means of the ostinato technique [die im “Sacre du printemps” durch Ostinatoverfahren geschaffen wird]. Here there are two frozen levels: the violin melody . . . and the drum pattern.” (Nepodvízhnost is defined in Taruskin as “immobility, stasis; as applied to form, the quality of being nonteleological, nondevelopmental” [Stravinsky and the Russian Traditions, 2:1678]). In his discussion of “frozen harmonies,” Jonathan D. Kramer writes the following: “Critics and analysts of Igor Stravinsky’s music have often noted his predilection for harmonic stasis. Particularly in music written during the 1910s, he created extended passages based on single chords or on the alternation of two chords. . . . Whatever the motivation, there are important consequences of his use of frozen harmonies” (“Discontinuity and Proportion,” 174).

12. In the early stages of his compositional process for Firebird, Stravinsky did not yet have a clear and distinct notion of the scenario in mind. Taruskin has confirmed that when writing the early sketches, “Stravinsky was unacquainted with the scenario and could not have known that the legend of Kashchey would figure in the ballet” (Stravinsky and the Russian Traditions, 1:580). Nevertheless, Stravinsky was preoccupied with tritonal configurations both melodically and harmonically. Intervals that he would experiment with melodically would sometimes be used harmonically in the sketches, the eventual outcome being that each “magical character” in the ballet was differentiated by motives that included a tritone, whereas the characters representing the human world of the princesses were represented by more traditional tonal patterns. Therefore, it appears that it became Stravinsky’s intention to establish this contrast between the magical and the human. In his retrospective comments about Firebird, Stravinsky claims that he was

still rather susceptible to the system of musical characterization of different people or of different dramatic situations. And this system shows itself in the introduction of processes belonging to the order of what is called Leitmotiv. . . . All that is concerned with the evil genius Kashchei, all that belongs to his kingdom—the enchanted garden, the ogres and monsters of all kinds who are his subjects, and, in general, all that is magical and mysterious, marvelous or supernatural—is characterized in the music by what might be termed a Leitharmony. . . .

In contrast with the magical chromatic music, the mortal element (the prince and the princess) is allied with characteristically Russian music of a diatonic type. (cited in Stravinsky and Craft, Stravinsky in Pictures and Documents, 60–61n124)

13. Or pitch classes 2, 4, 5, 8, which can be thought of as the tetrachord 4–12 (0236).

14. For a discussion of Stravinsky’s formulaic treatment of melodic patterns in the Carillon section of The Firebird, see Carr, “Le carillon féerique.”

15. This opera was written in 1901–1902 and published in St. Petersburg in 1902, with the conclusion revised in 1906; see Frolova-Walker, “Nikolay Andreyevich Rimsky-Korsakov,” 21:412.

16. Jonathan Cross also differentiates between “background” and “foreground” motives in The Rite of Spring (R-10 to R-12) in The Stravinsky Legacy, 96–98.

17. For a discussion of the different forms of this six-note pattern, or pitch-class set 6–7 (012678), from R-98 to R-101 in Stravinsky’s Firebird, see Carr, “Le carillon féerique,” 44.

18. An octatonic block (utilizing only six notes of the octatonic scale) without rhythmic differentiation is also found in the “Coronation Scene” of Mussorgsky’s Boris Godunov (1869 and 1872 versions). (Interestingly, Alexandre Benois was one of several designers who worked on this production. See Emerson and Oldani, Modest Musorgsky and “Boris Godunov,” 91–92.) The music of Boris Godunov was completely familiar to Stravinsky because his father frequently sang the role of Varlaam in performances of the opera at the Mariinsky Theater in St. Petersburg. This is not to say that the “Performance of the Mechanical Nightingale” is a literal quotation of the “Coronation Scene”; possibly it is a subconscious “reference” on Stravinsky’s part. For a discussion of “classical as reference,” see Pierre Boulez’s third category among attitudes of individuals of today with respect to the past in “Classique-Moderne.” In Multiple Masks, I argue that the influence of the “Coronation Scene” is evident in the sketches for Stravinsky’s Apollo (see 108–109). The reference to Boris in Apollo seems much more deliberate than this “subconscious reference” because it is pitch-specific.

19. Dina Lentsner translated this article from the Russian press for the 1914 Parisian season, from an interview with Stravinsky (untitled and undated).

20. Translation by Lynn E. Palermo. Later performances took place in London (18 and 29 June 1914, 14 and 23 July 1914).