One of music’s great revolutionary innovators, Igor Fyodorovich Stravinsky, was born in 1882 in late imperial Russia, the year after determined terrorists murdered Tsar Alexander II (1855–81), who had launched the Great Reforms in the aftermath of Russia’s disastrous defeat in the Crimean War (1853–56).1 During the forty-year period between Stravinsky’s birth and the end of World War I, Russia gave the world terrorism, Kropotkin-style anarchism, Dostoevsky’s messianic irrationalism, Tolstoy’s nonviolence, anti-Semitism, ballet and modern theater, abstract art, the dream of Communism, and, of course, The Rite of Spring, which Stravinsky composed during what musicologists call the “Russian stage” of his musical career.2 As a historian of Russian politics and society, I seek here to link the remarkable cultural ferment at that time to the question that has fueled impassioned debate among generations of historians and others as well: How politically viable was the Russian autocracy, especially during the reign of the last tsar, Nicholas II? He ruled between 1894 and March 1917, when bread riots instigated by irate women released a wave of revolutionary discontent that washed away the country’s antiquated political order, replacing it with something brashly different yet, at the same time, when taking the country’s autocratic political culture into account, all too familiar (see Figure 0.1).

Historians have long noted—and pondered the reasons for—the contrast between Russia’s brilliant artistic, cultural, and intellectual life at the turn of the twentieth century and the country’s turbulent politics. Stravinsky produced the music from his Russian stage during the explosive era in the history of Russian avant-garde art known as the Silver Age in Russian culture, when it was at one with Europe. Historian of Russian culture Wladimir Weidlé argued more than half a century ago that “all that Russia could later export in the way of artistic values . . . is wholly the work of this very short period. And it was an anything but peaceful period.”3 This was the period of the Moscow Art Theater, which, under Konstantin Stanislavsky, Vladimir Nemirovich-Danchenko, and Anton Chekhov, altered world stagecraft; of the experimental Ballets Russes; and of bold Russian paintings exhibited abroad.

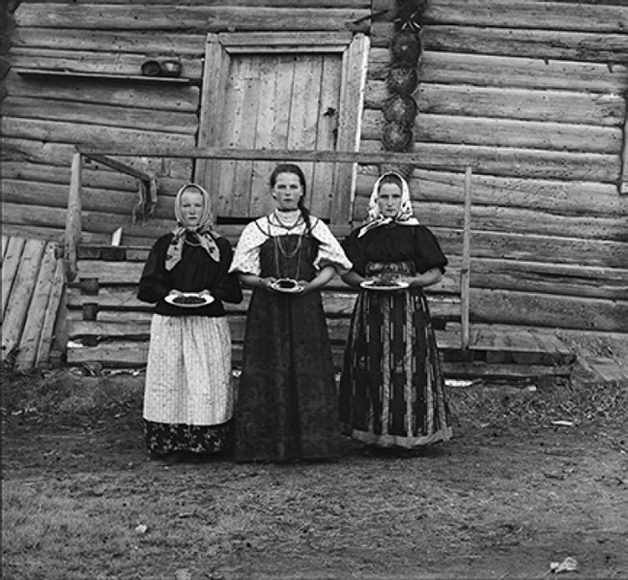

Figure 0.1. During the last decades of Russia’s old regime, a state-supported program of modernization began to narrow the gaping chasm between the country’s cultural elite and the unscrubbed peasant and worker masses. Industrialization, urbanization, and the spread of literacy, however, likewise exacerbated social differences. So did agrarian reform introduced in the years following the Revolution of 1905, which aimed to challenge traditional life in the villages by turning peasants into private farmers. The tsar’s photographer, Sergei Mikhailovich Prokudin-Gorskii, captured three young village women offering berries to visitors near the town of Kirillov in 1909. Sergei Mikhailovich Prokudin-Gorskii Collection, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.

Avant-garde Russian modernism arrived at what artist, theatrical designer, and producer Alexandre Benois described as a “spiritually tormented, hysterical time” characterized by a revolt against positivism—a philosophy of science—in the name of individualism, aestheticism, and religious and philosophical idealism, which touched all of the arts in Russia.4 The new zeitgeist gave rise to Symbolist, Acmeist, and Futurist poetry in Russia. The ferment in poetry influenced prose writers such as Anton Chekhov, Ivan Bunin (the first Russian writer to win the Nobel Prize for literature), and Maxim Gorky. Contemporaneous Russian music consisted of works by Modest Mussorgsky, Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov, Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky, and Mikhail Borodin, whose status was challenged in the 1890s by Alexander Scriabin and then by Stravinsky and Sergei Prokofiev. Young members of the creative intelligentsia found inspiration for their writing, art, and music not only in the modern West and in the allure of the Orient but also in Russia’s iconographic heritage, producing a spate of brilliant painters, including Vasily Kandinsky and Marc Chagall.

Contemporaries marked the beginning of Russia’s modernist movement with the launch in 1898 of impresario Sergei Diaghilev’s attention-grabbing publication Mir iskusstva (The world of art) (see Figure 0.2), which proclaimed, “Art is free, Life is paralyzed.”5 Although its detractors decried what it perceived as the publication’s “art for art’s sake” ideology, those who belonged to the World of Art movement saw the revival of Russian art as a safeguard against the towering authority of the bourgeois culture of Western Europe. A Russian nationalist at heart, Diaghilev, historian Steven Marks reminds us, had messianic expectations for Russian culture: “Its calling was nothing less than to transfigure all European culture, which was in ‘desperate need of Russian art.’”6 That is why, in 1907, Diaghilev, after losing interest in Mir iskusstva, organized a season of “Russian Music through the Ages” in Paris featuring the music of Tchaikovsky, Rimsky-Korsakov, Sergei Rachmaninoff, and Scriabin, among others. With intense confidence and zeal, he wrote at the time that European audiences were becoming worn out by Wagnerian fare, that “Viking world of bearded warriors drinking blood out of skulls.”7 In the wake of the success in Paris of that endeavor, in 1908 Diaghilev staged an extravagant production of Mussorgsky’s opera Boris Godunov. In 1909 he founded the Ballets Russes, determined to turn heads in the French capital by making his ballets lavish, controversial, and even scandalous.8 “I had already presented Russian painting, Russian music, and Russian opera in Paris,” the artistic genius recalled years later. “Ballet contains in itself all these other activities.”9 Until Diaghilev’s death in 1927, the Ballets Russes performed across Europe and North America and even in Argentina but, ironically, never in his native Russia: before the Revolution, the tsarist government had ostracized Russia’s native son, and after 1917, he steered clear of the Bolshevik experiment owing to his aversion to Red Russia.

The content of Silver Age culture is as important as its forms.10 Both the detractors and even, at times, the practitioners of these new trends used the terms decadence and decadentism.11 An escape from life, decadence, as generations of writers have indicated, promoted frenzied searching, fervent belief, aestheticism, mysticism, and idealism. Historian W. Bruce Lincoln stresses that decadentism likewise provided fertile ground for suicide, murder, sexual perversion, opium, and alcohol, all of which further distinguished Russia’s Silver Age, and all of which found reflection in belletristic, public affairs, and even philosophical writing of the time.12 In examining the “decadence” of Russian cultural life during Stravinsky’s Russian period, Librarian of Congress and Russian historian James Billington, in a classic account of Russian culture still worth reading today, identifies three themes that characterized it.13

Figure 0.2. The year before launching Mir iskusstva, Sergei Diaghilev claimed he saw the future through a magnifying glass. Readers of the World of Art must have agreed, for the publication championed the idea of art for art’s sake as it helped transform Russian visual culture’s aesthetic environment. Mir iskusstva 2, nos. 13–14 (1899). Courtesy Lilly Library, Indiana University, Bloomington, Indiana.

The first is prometheanism, the belief that man, when fully aware of his capabilities, is able to totally transform the world. Incidentally, Russian novelist, poet, religious thinker, literary critic, and nine-time nominee for the Nobel Prize in literature Dmitri Merezhkovsky translated and in 1892 published Aeschylus’s Prometheus Bound.14 The second theme is sensualism, a sensual reaction against long-dominating moralism and ascetic puritanism. As Billington notes, cosmic prometheanism was accompanied by a “counter-current of personal sensualism; boundless public optimism, by morbid private pessimism.”15 The preoccupation with sex during this period remains unparalleled in Russian culture, made possible by the repeal of censorship during the Russian Revolution in 1905. High priest of the Silver Age’s new cult of sex, writer Vasily Rozanov, even preached that “the tie of sex with God is far stronger than the tie of intellect.”16 Enter Rasputin. Perhaps he remains the most characteristic symbol or symptom of this sinister time. A fraudulent starets, or “holy man,” Rasputin preached the doctrine of salvation through sin, and by sin he meant sex: “If God sends us temptation,” reasoned Rasputin, “we must yield to it voluntarily and without resistance, so that we may afterward do penance in utter contrition.”17 As historian Laura Engelstein observes, “Sexual disarray at the pinnacle of power came to stand for what was wrong with the tsarist regime.”18

The third theme is apocalypticism, or prophetic revelation, which Billington suggests is the by-product of an unresolved psychological tension between prometheanism and sensualism. Evocative and compelling examples of the apocalyptic pepper the literature and philosophical ruminations of Russia’s Silver Age, about which I will say more later. Suffice it for now to observe that in 1900 philosopher Vladimir Soloviev had already raised the alarm, “warning of a new Mongol horde in Asia and of the end of civilization.”19 These preoccupations, writes Billington, “helped to sweep Russia further away from its moorings in tradition” as members of the intelligentsia “drifted from one current to another.”20

In cultural terms, Russia throughout the Silver Age was nearly one with Europe, but this was not true politically during what the French call the Belle Époque and the British the Edwardian Age. This period of extraordinary advancements in science and technology—such as the telephone, electric lights, the automobile, the first motion picture, the first airplane—also witnessed the growing influence of parliaments and the expansion of suffrage. Yet, entering the twentieth century, Russia was one of only two European countries that lacked a parliament. Politically, Russia remained an autocracy, characterized by administrative centralism, a large and imperfectly emancipated peasant majority, a small industrial class, a modicum of representative institutions (namely, provincial bodies known as zemstvos, and town councils, or dumas), and a restless professional (rather than commercial) middle class demanding greater political clout, now all under assault from a program of state-sponsored rapid industrialization and modernization that yielded some of the highest growth rates the world had seen. The government’s suspiciousness of popular initiative—which it unfortunately saw as opposition—revived in the 1890s the country’s revolutionary movement, which now included Marxist groups that competed with Russian agrarian socialism as an industrial proletariat exploded onto the scene and a bona fide labor movement emerged.21

Generations of historians have asked two broad questions about politics during Nicholas II’s reign. First, was he the blind, indecisive, ineffective, and even ill-starred monarch perceived by his contemporaries and subsequently by historians? Second, on the eve of World War I, was Russia organically evolving toward some kind of democratic order or heading ineluctably toward revolution? Just about all historians accept Nicholas’s own statement that, despite his appealing personal qualities, he was unfit to rule. Even his most sympathetic biographers believe that the pathos of his tragic end saved him from the dustbin of history. For example, Pulitzer Prize–winning author Robert Massie, who wrote one of the most empathetic biographies of Nicholas, maintains: “The virtues which we admire in private life and profess in our religion become secondary qualities in our rulers. The test of greatness in tsars or presidents is not in their private lives or even in their good intentions, but in their deeds.”22 Virtually all but a small handful of studies (mostly authored by Russian émigrés who fled the country during the Revolution or by Russian monarchists of today) furnish a consistently pessimistic and harshly critical judgment of this reluctant, traditionalist leader.23

There is good reason for this. The government’s cruel gunning down of a procession of unarmed workers on 9/22 January 1905, known as Bloody Sunday, destroyed whatever belief may have remained in popular consciousness of the notion of a good tsar served by bad officials, triggering revolt and ushering in a year of revolutionary challenge to the autocratic system. Galvanized by an unpopular war against Japan that Russia ultimately lost, the population resorted to strikes, mutinies, rural violence, and workers’ revolt. When the tsar’s minister suggested liberal reform, Nicholas barked: “Under no circumstances will I ever agree to a representative form of government.” Wrote his minister of the interior, “Everything has failed. Let us build jails.”24 But a general strike in October 1905 brought the government, and Nicholas, to their knees, forcing the autocrat to grant full civil liberties and create a representative assembly, the Duma, elected indirectly but with legislative powers.

This could have been a turning point in Russian history. In a sense it was: it doomed the autocracy. Nicholas dismissed the First Duma after seventy-three days. The Second Duma “of popular anger” lasted only three months. Then, on 3/16 June 1907, the government changed the electoral law, thereby disenfranchising most citizens, especially those from the lower classes and the country’s national minorities, to create a docile parliament. Concluding that the Russian autocracy had sentenced itself, historian Andrew Verner reasons that “with the crisis of 1905–1906, its ultimate fate had been decided; the ten years remaining until 1917 were little more than a death rattle.”25 True, the Third Duma survived its legal five-year term. Elected in 1912, the Fourth Duma was outwardly even more conservative. But just prior to the war it carried the strongest motion on record, denouncing the Ministry of the Interior’s scorn of the Duma and of public opinion. “Such a situation,” reads the Duma resolution, “threatens Russia with untold dangers.”26

Figure 0.3. Russia’s entry into World War I marked the beginning of a political, social, and demographic earthquake that lasted into the 1920s. The country mobilized 12 million citizens, of whom 1.7 million perished and almost 5 million were wounded. Another 2.5 million were taken prisoner of war or declared missing. Many millions more died or fled the country during the Revolution, Civil War, and famine of 1921–22. National Geographic Magazine 31 (1917): 369, panel A.

Historical scholarship has proved far less unanimous in answering the more controversial question about the country’s political health. Historian Robert Service recently reminded us that “no imperial power before the First World War was more reviled than the Russian empire.”27 But its overthrow resulted in the Bolsheviks coming to power, not in liberal democracy. Conducting an ideological contest with Communism, Cold War scholarship, as a result, viewed Soviet society with antipathy, fear, and disdain, transferring these hostilities back to the Revolution. The Bolsheviks illegitimately seized power, according to historians, public affairs writers, and Russian émigrés, only owing to Russia’s disastrous showing in World War I (see Figure 0.3). In short, war ruined the potentiality for nonrevolutionary modernization. Until the 1960s, this optimist strain prevailed in much of the academic and popular literature, which underscored the promising parliamentary system, real gains in education, industrial growth, and a mushrooming cooperative movement. Placing overwhelming blame on the war as the cause of the Revolution of 1917, some optimists believe even war could have been weathered if it were not for the character of the tsar and tsarina (see Figure 0.4).28

In the 1960s, however, several historians articulated compelling pessimistic assessments of the viability of late imperial Russia. In their view, war merely brought an ailment to its crisis. Most notable is the “even without war” approach of historian Leopold Haimson, which emphasizes a growing strike movement after 1912, emboldened following the Lena Goldfields Massacre, when soldiers fired at and murdered unarmed workers. Haimson’s approach also examines the polarizations in Russian society: first, between educated society and the official bureaucracy, which would have resulted in the overthrow of the tsar (in other words, the February Revolution of 1917); and second, between educated society and the masses, which would have frustrated efforts at a constitutional order (resulting in the October or Bolshevik Revolution).29 This perspective predominated in Western scholarship among a new generation of historians until the end of the Soviet project. It coincided with real reform in the Soviet Union, an exchange program that made it possible for American graduate students to live and conduct research in the USSR, the student movement and disillusionment in the United States over the Vietnam War, and a contested shift within academia from political to social history. The latter resulted in a flood of dissertations on workers, soldiers, peasants, women, and national minorities, the first studies of provincial Russia, and so on, that is, on actors heretofore largely absent from the historical writing on the Russian Revolution. Virtually all of this work—which is far too voluminous to cite here—casts grave doubts on the political viability of the old regime.30 A case in point is Joan Neuberger’s study of hooliganism in Russia’s capital, in which the author argues that hooliganism “convinced a significant portion of society . . . that Russia’s capacity to assimilate its poor into cultured society and become a civilized and politically unified nation was diminishing with each passing day.”31 Moreover, the new scholarship and the behavior of post-Stalin Soviet leaders challenged the reigning intellectual paradigm in academic scholarship, which viewed the Soviet Union as a totalitarian (and largely illegitimate) regime.32

The demise of the Soviet experiment and the spirit of the 1990s that naively heralded the end of history and the triumph of market capitalism and liberal democracy, however, resulted in a nostalgic love affair with imperial Russia. Communism had been illegitimate and an aberration all along, this line of reasoning goes, and now Russia was returning to an organic path of development interrupted by war and the Bolshevik Revolution. More importantly, a number of new historical works call into question the interpretation privileging social polarization to underscore the vibrancy before 1914 of Russia’s emerging public sphere, heretofore often overlooked. As historian Wayne Dowler writes, “If Russia was still far from becoming a liberal capitalist democracy in 1913, it was even farther from socialist revolution. Severe stresses and tensions remained, but the clear trend before the war was toward cooperation and integration. The passage of time in peaceful circumstances would likely have strengthened the middle-class liberal discourse at the expense of its opponents.”33 Such studies suggest that relations within and among social groups in Russia were more complex and less polarized than those that insist Russia was on an inevitable path toward social revolution would argue.34

Figure 0.4. The Romanov dynasty celebrated its tercentenary in 1913, the year before the empire became embroiled in the Great War. That May, Nicholas II and Alexandra Fyodorovna retraced the journey Tsar Mikhail Romanov made back in 1613. The extravagant celebrations and public involvement in the pageantry obscured the critical nature of public opinion, which would turn even more against them during World War I. (Photograph taken in 1913 or 1914.)

Yet I find it hard to disagree with historian Christopher Read, who observes that “in recent decades tsarism has been getting away with murder,” since, in the early years of the century, it was “treated with opprobrium comparable to that which, in more recent times, has been reserved for the apartheid regime in South Africa.” Despite the almost universal repugnance engendered in humane contemporaries inside and outside the empire, the reign of Nicholas II became “the subject of an unlikely, slow-burning but insistent revisionism geared to show it was not so bad after all.” The peak of this, in Read’s view, was the Russian Orthodox Church’s canonization of Nicholas II in 2000. Didn’t the tsarist autocracy bear some of the responsibility for the crimes of its successors? Read asks.35

This is a valid point. Moreover, in revisiting a 1962 work by American government official Jacob Walkin that optimists routinely cite to show the democratic valence of Russian political culture, Read underscores the extent to which Walkin emphasizes not only the emergence of civil liberties but also what he calls “the unbridgeable gulf between state and society.” Read reminds us that “the early optimists saw tsarism as an obstacle to democratization and modernization of society and economy.” To his credit, he also discusses scholarship published in the 1970s that offers support for at least a modicum of optimism, resulting in “a more complex interpretation than the caricatural view of an unrelievedly wicked tsarism and an heroic and near-faultless opposition which one not infrequently encountered in the sixties and early seventies.”36

I would add that bourgeois modernity was not tsarism’s ally but its enemy. The discourse of civil society for the most part subscribed to a vision of social and political modernity that had little tolerance for the rigidity of the old regime. Moreover, this weakly developed discourse competed with much stronger strains of anticapitalism and distrust of the bourgeoisie, as well as with a deeply embedded notion of Russian exceptionalism, neither of which boded well for Russia’s peaceful evolution into a democratic monarchy. While true that, in the short term, war led to the collapse of the system, none of the deep fault lines in Russian society had anything to do with the war. These fault lines included the failure of the Duma; extreme Russian nationalism, which proved unfortunate for the country’s populous minorities and led to an adventurist foreign policy; the character of Nicholas II; and the revolutionary movement, which drew youth into an attitude of defiance and which revived after 1911.37

The lessons here are obvious: historians’ views and interpretations are historical and subjective, reflecting the spirit of the times in which they are articulated and the historians’ personal experiences and belief systems. This is not unlike the view of the dramatis personae who populate our books. Take Igor Stravinsky’s monarchism, an understandable position, given his privileged status; his anti-Semitism, given its public nature in late imperial Russia; and his intense Slavophilism and later association with Fascism, given his formative experience and later alienation as an uprooted émigré hostile to Communism.

In his 2001 study Stravinsky Inside Out, Charles M. Joseph reminds us that “to ignore the politics of the age . . . to underestimate the social context in which he participated as a very public figure, only crystallizes the many half-truths that swirl around his image.”38 Yet Joseph ignores Stravinsky’s early years in late imperial Russia. While Russia was nearly one with Europe at this time, one of the three trends that Billington identifies in Silver Age decadence was more peculiarly Russian—apocalypticism. “Nowhere else in Europe,” concludes Billington, “was the volume and intensity of apocalyptic literature comparable to that found in Russia during the age of Nicholas II.”39

Apocalyptic writing turned into a flood on the eve of the Great War. As answers to metaphysical questions about art, God, and human destiny eluded them, some Russians declared the Antichrist was coming, warning of the imminent struggle about to engulf mankind. They believed that Halley’s Comet, which shot across the heavens in 1910, heralded the approaching close of an epoch. That year Lev Tolstoy, artist Mikhail Vrubel, and Russia’s popular actress Vera Kommissarzhevskaya died. People saw these passings as signs of a greater catastrophe to follow. For instance, Slavic studies scholar William Nickell, who depicts the public drama surrounding Tolstoy’s death as Russia’s first great mass media event, suggests that Russians believed something precious and important had died forever at Astapovo stationhouse, where Tolstoy succumbed to pneumonia at age eighty-two.40 As poet Alexander Blok (born two years before Stravinsky) remarked when Tolstoy turned eighty, as if anticipating the writer’s death, “While Tolstoy is alive, and going along the furrows behind a plough, behind his white horse, the morning is still fresh and dewy, unthreatening, the vampires sleep, and—thank god. . . . Here comes Tolstoy—indeed, it is the sun coming up. But if the sun sets, Tolstoy dies, the last genius leaves—what then?”41 In 1911 a Moscow newspaper warned of war as riotous strikes erupted in London, and an assassin gunned down Russia’s prime minister, Pyotr Stolypin. In 1912 soldiers, confronted by striking gold miners, fired on unarmed protesters. Reverberating across Russia, the massacre revived the strike movement and unified much of public opinion against the autocracy.42

Thus, when the Romanov dynasty celebrated its tercentenary in 1913 the event, successful on the surface, revealed the isolation of the imperial family. That year the infamous anti-Semitic Beilis Trial, which inspired Bernard Malamud’s The Fixer, captured world public opinion. On 8 March Russian revolutionaries for the first time celebrated International Women’s Day, an event that four years later became the opening salvo of the revolution that brought down the autocracy. The otherwise docile and progovernment State Duma protested that the tsar’s ministers ignored it. Writer Andrei Belyi began serializing his acclaimed Petersburg, a novel chock-full of apocalyptic imagery. That May Igor Stravinsky’s ballet opened in Paris. And this on the eve of the Great War, which the wily Rasputin admonished Nicholas II to avoid at all costs.43

Postrevolutionary historical scholarship has framed this era according to contemporaneous issues. Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring and the essays that follow get us back to the historical moment.

1. For a discussion of Alexander II and his Great Reforms, see Zakharova, “Emperor Alexander II”; and Eklof, Bushnell, and Zakharova, Russia’s Great Reforms.

2. For an accessible and authoritative discussion of Russia’s contributions to the modern world, see Marks, How Russia Shaped the Modern World.

3. Weidlé, Russia, 89.

4. Benois cited in Bowlt, Russian Art, 3. See also his The Silver Age. For the Ballets Russes, see Garafola and Baer, The Ballets Russes.

5. For Diaghilev’s view, see Diagilev, Sergei Diagilev i russkoe iskusstvo. For the rise of the publication, see Benois, Vozniknovenie “Mira iskusstva,” 5–19. For a comprehensive account of the movement, consult Kennedy, The “Mir iskusstva” Group.

6. Marks, How Russia Shaped the Modern World, 179.

7. Quoted in ibid., 182.

8. See Garafola, Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes.

9. Cited in Haskell and Nouvel, Diaghileff, 176.

10. In a recent study of why the period remains prominent in Russian collective consciousness, literary scholar Galina Rylkova (The Archaeology of Anxiety) considers the period as the by-product of an all-pervasive anxiety created by the political, social, and cultural upheavals associated with World War I, the Revolution, the Civil War, and the dark years of Stalinism. Analyzing the writings of Anna Akhmatova, Vladimir Nabokov, Boris Pasternak, and Victor Erofeev, she argues that the Silver Age became a key ingredient of Russian cultural survival.

11. See, for example, Rosenthal, Dmitri Sergeevich Merezhkovsky.

12. Lincoln, In War’s Dark Shadow, 351.

13. Billington, The Icon and the Axe. Also of interest is his The Face of Russia.

14. The translation first appeared in his Simvoly. See also Wells, “Merezhkovsky’s Simvoly,” 61.

15. Billington, The Icon and the Axe, 492.

16. Quoted in Lincoln, In War’s Dark Shadow, 354, citing Poggioli, Rozanov, 34–37.

17. Lincoln, In War’s Dark Shadow, 383. His source is Fülöp-Miller, Rasputin, 215. For an up-to-date, authoritative account of the false starets, see Fuhrmann, Rasputin.

18. Engelstein, The Keys to Happiness, 421.

19. Lincoln, In War’s Dark Shadow, 385.

20. Billington, The Icon and the Axe, 513.

21. See Stavrou, Russia under the Last Tsar; and Katkov et al., Russia Enters the Twentieth Century.

22. Massie, Nicholas and Alexandra, xiii.

23. Until the opening of the Russian archives, only a handful of accounts of Nicholas II existed. In 1922 émigré historian Sergei S. Ol'denburg authored Gosudar' Imperator Nikolai II Aleksandrovich. After fleeing the Soviet Union, he published the most sympathetic account of the tsar at the time, Tsarstvovanie Imperatora Nikolaia II. A second edition appeared in 1981. Not surprisingly, given the heady optimism of the first post-Soviet years and temporary nostalgic embracing of the country’s tsarist, prerevolutionary past, the study was issued in Moscow in 1991. Ol'denburg’s biography appeared in English as Last Tsar: Nicholas II, His Reign and His Russia. Drawing on newly available material, British historian Dominic C. B. Lieven authored Nicholas II: Emperor of All the Russias, published in 1994 in the United States as Nicholas II: Twilight of the Empire. Placing Nicholas within a larger international context by comparing him to other rulers in Japan, Germany, and Persia, Lieven casts him as an anachronistic and patriarchal leader constrained by tradition, a powerful bureaucracy, and an inability to adapt to change. Portraying Nicholas II as a naive, pleasure-seeking ruler who belonged to an imperial family riven by dysfunction, French historian Marc Ferro also tapped new materials for his Nicholas II: The Last of the Tsars in 1993. During the Soviet era, historians privileged social classes, not individual rulers, as a result of which Soviet scholarship produced no biographical account of Nicholas II but made a cottage industry of issuing studies of exploited workers and peasants destined to overthrow the tsarist autocracy. Some of these works remain essential reading to historians of the period, especially those of A. Ia. Avrekh, who, after the dissolution of the Soviet Union, authored Tsarizm nakanune sverzheniia in 1989, a critical account of tsarism on the eve of its downfall. Historian and playwright Edvard Radzinsky, now a U.S. citizen, published biographical accounts not only of Alexander II and of Rasputin but also of Nicholas II: The Last Tsar: The Life and Death of Nicholas II. Weaving together scraps of information from previously unavailable royal diaries and letters, the testimony of executioners, and what friends, relatives, and descendants had to say about Nicholas and his family, Radzinsky confirms the tsar’s ineffectiveness as a ruler (and Alexandra’s frail psyche), despite his personal charm. Historians Boris Vasilievich Ananich and Rafail Sholomovich Ganelin, corresponding members of the Russian Academy of Sciences who devoted their careers to illuminating aspects of the reign of Nicholas II, authored a hard-hitting biographical account that suggests that no matter how sympathetic one might be to Nicholas and his plight, it is difficult to present him in anything other than a negative light. See their “Emperor Nicholas II, 1894–1917,” in Raleigh, The Emperors and Empresses of Russia, 369–402. Russian historian A. N. Bokhanov, whose intellectual journey after the dissolution of the Soviet Union led him to embrace monarchy as the most appropriate political form for Russia, authored studies that correspond to his personal ideology. See his Nikolai II, Imperator Nikolai II, and Poslednii Tsar'. Taking the cultural turn, St. Petersburg historian Boris I. Kolonitskii published several acclaimed works that underscore the extent to which the Romanov dynasty, and Nicholas II in particular, became desacralized in Russian society on the eve of revolution. See his Simvoly vlasti i bor'ba za vlast' and “Tragicheskaia erotika.” For a supplemental discussion of new writing on the last Romanov published in the 1990s, see Steinberg and Steinberg, “Romanov Redux.”

24. Cited in Gurko, Features and Figures of the Past, 304.

25. Verner, The Crisis of Russian Autocracy, 6.

26. Quoted in Riha, “Constitutional Development in Russia,” 111.

27. Service, A History of Twentieth-Century Russia, 1.

28. See, for instance, what has become known as almost a classic statement of this position: Mendel, “On Interpreting the Fate of Imperial Russia.”

29. Haimson, “The Problem of Social Stability in Urban Russia.” Some thirty-five years later, Haimson revisited the so-called Haimson thesis. In doing so, he stuck to his guns; however, he acknowledged that the start of war temporarily papered over social polarizations, which resurfaced with new force as the war progressed. See his “‘The Problem’ . . . Revisited.”

30. In my Revolution on the Volga, I stress the extreme likelihood of a revolution that would remove Nicholas II from power, but I argue that war was necessary for a Bolshevik victory.

31. Neuberger, “Culture Besieged,” 187. Also see her Hooliganism.

32. See Stephen F. Cohen’s discussion of Sovietology as a profession and the totalitarian model in his Rethinking the Soviet Experience, 3–37.

33. Dowler, Russia in 1913, 279.

34. I especially have in mind Lindenmeyr, Poverty Is Not a Vice; Bradley, Voluntary Associations in Tsarist Russia; and, on the rise of leisure, literacy, and the professions, McReynolds, The News under Russia’s Old Regime, Russia at Play, and Murder Most Russian.

35. See Read, “In Search of Liberal Tsarism,” 195, 196.

36. Ibid., 197–200. See Walkin, The Rise of Democracy.

37. George F. Kennan forcefully makes this point in connection with the fiftieth anniversary of the Bolshevik Revolution. See his “The Breakdown of the Tsarist Autocracy.” He also argues that the autocracy missed the decisive chance to prevent revolution already in the 1860s.

38. Joseph, Stravinsky Inside Out, x.

39. Billington, The Icon and the Axe, 514.

40. Nickell, The Death of Tolstoy.

41. Cited in Meek, “Some Wild Creature.” For Blok’s statement in Russian, see Privalov, “O Tolstom.”

42. Michael Melancon (The Lena Goldfields Massacre) argues that this event questions the depth of polarization in Russian society; however, the near-universal outcry against the government’s inept handling of the strike demonstrates the autocracy’s vulnerability, for the event must be read as a portent of emerging social consensus that change was necessary.

43. The war itself only served to intensify apocalyptic writing. See, for instance, Stroop, “Nationalist War Commentary.”