six

Transportation and the Hulks

TRANSPORTATION TO AMERICA

The shipping of felons to Britain’s overseas colonies began in 1615, during the reign of James I, and continued, on and off, for the next 250 years. The use of transportation was first introduced as a piece of Poor-Law legislation in the 1597 Vagabonds Act. It provided that ‘rogues, vagabonds, and sturdie beggars’ could be ‘banished out of this realme, and … conveied unto such parts beyond the seas’. 89 The statute also decreed that such undesirables could be put to service manning galley ships – a type of vessel not much used in England.

Initially, the transportation of convicted lawbreakers was on a voluntary basis, with only a few hundred offenders taking this option up to 1650. The most common destinations were the American settlements of Virginia and Maryland – where the new arrivals were sold as labourers to plantation owners at dockside auctions. Despite attempts in the 1670s by the colonies to halt transportation, the second half of the century saw its use increase with around 5,000 convicts being despatched there.90 For Britain, transportation had the benefits of both removing serious offenders from its shores and providing a much-needed labour force for its New World territories. By 1775 the total transported had grown to more than 30,000, with two-thirds of all felons convicted at the Old Bailey now being sent to the colonies and sold as servants.91 This was a policy which one pamphleteer in 1731 applauded as ‘Draining the Nation of its offensive Rubbish, without taking away their Lives’.92

Among the beneficiaries of the transportation policy were the merchants contracted to ship the convicts to their new homes. It was profitable business as the outgoings were relatively small and the returns high. Contractors were required to pay each prisoner’s gaol discharge fees (typically £1) and feed them during the voyage (at a weekly rate of 2s 6d during the eight-week crossing). Other overheads included crew, ship, port and administrative costs (around £2 per head), hire of irons (1s per head) and import duty (£1 per convict), giving a total expenditure of around £5 1s per convict.93 On the income side, merchants received a fee of £5 per head for transporting the convicts, plus whatever they could get for them at the quayside auction on arrival at their destination port. Typical prices were £15 to £25 for males with useful trade skills, £10 for common thieves and £8 for female convicts. The old and the infirm, however, had to be given away. On a good trip, a merchant could expect to clear an average profit of £9 to £15 per convict. On top of this, the return voyage to Britain, with a cargo of tobacco or grain on board, could generate a further healthy income.

The typical weekly food ration for those being transported comprised 1.2lb of beef and pork, 13.3oz of cheese, 4.7lb of bread, 0.5 quart of peas, 1.7 quarts of oatmeal, 1.3oz of molasses, 0.5 gill of gin and 5.3 gallons of water, providing a total of just 1200 calories a day.94

For the American recipients of this human traffic, the deliveries proved increasingly unwelcome – a feeling summed up in a 1751 letter (attributed to Benjamin Franklin) in the Pennsylvania Gazette, which proposed that the colonies should repay the kindness of mother England by exporting rattlesnakes to the British Isles and releasing them in St James’ Park.95 Attempts by the colonies to curtail transportation – by charging a duty on each convict landed, or a bond to ensure their good behaviour once in service – all proved unsuccessful and the convict ships continued to arrive until the outbreak of the War of Independence in 1775.

ALTERNATIVES TO TRANSPORTATION

The war with America brought an abrupt halt to the steady stream of convict ships that had been heading to its shores. What did not abate, however, was the flow of convicts sentenced to transportation by the courts, and a crisis in prison overcrowding soon began to loom.

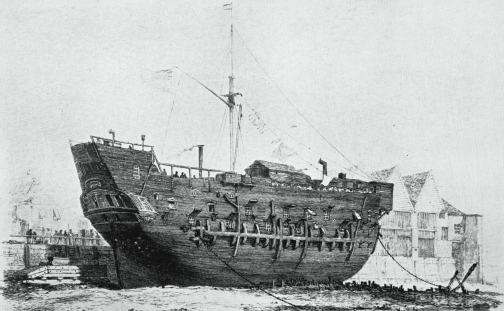

The immediate, and supposedly short-term, solution was to turn two of the hulks of old battleships berthed on the Thames at Woolwich into floating prisons for 100 inmates. At the same time, two pieces of parliamentary legislation were prepared which proposed longer-term remedies for the problem. The first, the Criminal Law Act of 1776, aimed to extend the use of shipboard prisons. It recommended that transportation be replaced by a period of hard labour lasting between three and ten years, with offenders held in houses of correction or ‘some proper place of confinement’ and fed on a diet of ‘bread, and any coarse meat, or other inferior food, and water, or small beer’. Although the Act made no explicit mention of shipboard prisons, the particular form of hard labour that it proposed – ‘removing sand, soil, and gravel from, and cleansing the River Thames’ – makes it clear that was where its intent lay. Despite some objections, such as the possible nuisance caused to nearby residents, and concerns about the security of the vessels, the bill was passed in May 1776.96

The second bill brought before parliament, but which took another three years to receive approval, proposed the erection of a pair of ‘Penitentiary Houses’ (one for 600 men and one for 300 women) on a site near to London. The houses would impose a strict regime with ‘labour of the hardest and most servile kind’.97

THE HULKS

In August 1776, the contract for supplying and managing the new prison ships, or hulks as they became known, was awarded to Duncan Campbell – one of the merchants who had previously been engaged in transporting convicts to America. Campbell’s initial contract was to provide a ship to house 120 prisoners for each of which he was to receive £32 a year. The first vessel he provided, the Justitia, was joined the following year by the Tayloe, the two then accommodating 240 prisoners. The Tayloe was soon replaced by the much larger Censor.

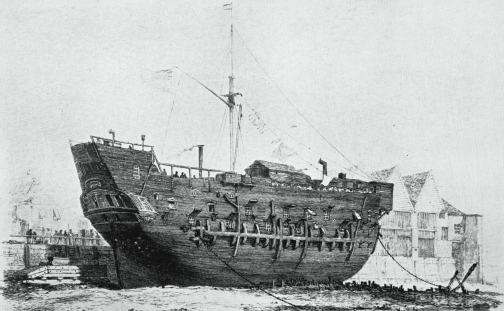

The ships were moored in the middle of the Thames at Woolwich Warren – a mass of foundries, workshops, warehouses and barracks, and a long-established home of naval ship-building and arms manufacture. During the day, prisoners worked at dredging the river or providing labour for building works. At night they were crammed below decks, originally in beds, and then in pairs on low wooden platforms, 6ft by 4ft. During the day, the platforms were stood on their side and used as tables. An experiment in using hammocks for beds was abandoned after it became apparent how difficult these were to use while wearing chains.98

John Howard, visiting the Justitia in 1776, discovered that the bread provided for the prisoners was mostly crumbs and ‘mouldy and green on both sides’. However, the captain assured him that ‘they would soon be out of the mouldy batch’.99 The meat used on the ship mostly came from the heads of butchered cattle, obtained at minimal cost from the slaughtering yards at Tower Hill, 3 miles upstream. A barely edible dish of ‘ox cheeks’ was served up five days a week but had often gone off. The convicts dined in groups or ‘messes’ of six and the daily menu for each mess in the early 1780s is shown below.100 There was also a daily ration of 7lb of bread per mess.

Breakfast |

Every day: a pint of barley or rice made into three quarts of soup. |

Dinner |

Sunday: six pounds of salt pork or seven pounds of beef with five quarts of beer. Monday, Wednesday, Friday: six pounds of bullock’s head. |

Supper |

Sunday, Monday, Wednesday, Friday: A pint of pease and barley made into three quarts of soup. Tuesday, Thursday, Saturday: A pint of oatmeal made into burgou. |

‘Burgou’ (also spelled burgoe or burgoo) was a thick oatmeal porridge. Two methods for making burgoo were provided by William Ellis in 1750 which he described as ‘best’ and ‘worse’. Presumably, convicts on the hulks would have been given the second version.

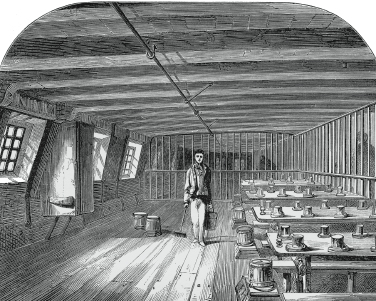

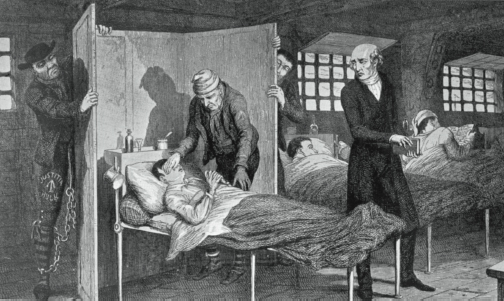

Conditions on the hulks were dire, with ships sometimes housing up to 700 convicts. At night, they were crammed below deck and left in the charge of a single warder. In the first twenty years of their operation, the hulks received around 8,000 prisoners, of which almost a quarter died on board. As well as diseases, such as gaol-fever, tuberculosis, cholera and scurvy, severe depression appears to have been common. During the first two years of the hulks’ operation, one physician commented that some of his patients had died ‘merely of lowness of spirit, without any fever or other disorder upon them’.102

The lack of progress in building a land-based penitentiary led to a steady growth in the number of hulks required to house the growing convict population. By 1788, the fleet included the Stanislaus at Woolwich, the Dunkirk based at Plymouth, the Lion at Gosport, and the Ceres and La Fortunee at Langstone Harbour. However, the role of the convict hulks as long-term prisons was about to come to an end.

TRANSPORTATION TO AUSTRALIA

Britain’s war with America ended in 1783 and resulted in the permanent loss of the American colonies as a destination for Britain’s convict ships. Despite there being no immediate alternative yet available, parliament passed an Act 103 reaffirming its belief in the use of transportation. Although Africa was briefly considered as a destination, the place that soon emerged to take on the role was Australia, claimed for Britain by Captain James Cook in 1770. It was decided to found a British prison colony at Botany Bay, the place where Cook had made his first landfall.

The first Australian convict convoy, the so-called First Fleet, comprised the flagship HMS Sirius, an armed tender, three store ships and six convict transports. 104 As with the hulks on the Thames, the convicts’ accommodation was provided by private contractors. The fleet set sail from Portsmouth on 13 May 1787 carrying 565 male and 192 female convicts, 13 children of convicts, 206 marines with 46 members of their families, 20 officials, 210 seamen of the Royal Navy, and 233 merchant seamen. Commanding the fleet was Captain Arthur Phillip, RN, who was to become the governor not just of the new penal colony, but also of the whole territory of New South Wales where the prison was to be Britain’s first permanent settlement.

As well as its human cargo, the First Fleet carried a vast amount of supplies to help the settlers establish the new colony. Two years’ supply of food and drink included 448 barrels of flour, 135 tierces of beef, 165 tierces of pork, 50 puncheons of bread, 110 firkins of butter, 116 casks of dried peas, 5 casks of oatmeal, 5 puncheons of rum, 300 gallons of brandy, 3 hogsheads of vinegar and 15 tons of drinking water. For their shelter and comfort on arrival, the ships carried 800 sets of bedding, 40 tents for female convicts, 26 marquees for married officers and a portable canvas house for Governor Phillip. Lighting was provided by 2½ tons of candles, plus 44 tons of tallow with which to make further stocks. Building tools included 700 felling axes, 175 steel hand-saws, 50 pick-axes, 700 shovels, 700 spades, 40 wheel-barrows, 12 brick moulds, 175 hammers, 747,000 nails and 5,448 squares of glass.

To establish agricultural production, 100 bushels of wheat, barley and corn seeds were supplemented at Rio and Cape Town by fig trees, bamboo and banana plants, sugar cane, and coffee and cocoa seeds. Cape Town also contributed to the fleet’s livestock with 7 cows, a bull, 3 mares, a stallion, 44 sheep, 19 goats, 32 hogs, 18 turkeys, 29 geese, 200 fowls and chickens, 35 ducks, kittens and puppies, and 5 rabbits. Fishing equipment comprised 14 fishing nets, 8,000 fish hooks, 48 dozen lines, 18 coils of whale line and 6 harpoons. Finally, to nourish the spirit as well as the body, the inventory included a Bible and prayer-book, a box of books and one piano.105

The passage took eight months – five times the duration of the crossing to America – and the fleet reached Botany Bay at the end of January 1788. Having surveyed the terrain, Governor Phillip decided that the new colony should be established a few miles to the north of Botany Bay at Port Jackson, now part of Sydney Harbour. Despite an outbreak of dysentery while crossing the Indian Ocean, the fleet suffered only forty-eight deaths on the voyage, a low rate which owed much to the efforts of the principal surgeon, John White, who insisted on fresh fruit and vegetables being obtained at each port en route, together with cleanliness in the cramped quarters below decks and regular exercise.

The colony had a shaky start, having to contend with illnesses such as scurvy, the failure of crops, limited fresh water supplies and trees whose hardness made them impossible to cut down. Discipline, too, was a problem – as well as insubordination from the prisoners, many of those that had been engaged as guards for the voyage refused to help keep order once the crossing had been completed. Finally, the native aborigines proved less than friendly – perhaps having a premonition of the devastation that was to come in 1789, when an outbreak of smallpox killed almost half of their number in the area.106

At the end of 1789, a second convict fleet carrying much needed supplies had been delayed, and a serious food shortage was facing the colony. By February 1790:

There remained therein not more than four months’ provisions for all hands, and this at half rations. To prepare for the worst, the allowance issued was diminished from time to time, till in April, that year, it consisted only of 2lbs. of pork, 2lbs. of rice, and 2½lbs. of flour per head, for seven days. More than ever in the general scarcity were robberies prevalent. Capital punishment became more and more frequent, without exercising any appreciable effect … [One] old convict said that he had often dined off pounded grass, or made soup from a native dog. Another old convict declared he had seen six men executed for stealing twenty-one pounds of flour. ‘For nine months,’ says a third, ‘I was on five ounces of flour a day, which when weighed barely came to four. The men were weak,’ he goes on, ‘dreadfully weak, for want of food. One man, named ‘Gibraltar,’ was hanged for stealing a loaf out of the governor’s kitchen.’ 107

Conditions were also grim on board the transport ships of the Second Fleet, which finally arrived at Port Jackson in June 1790 after losing one of its stores ships to an iceberg. Of the 1,000 or so convicts that set out, more than a quarter perished at sea. A further 150 died not long after coming ashore. The largest transport ship in the fleet, the Neptune, accommodated its 421 prisoners on a lower deck measuring no more than 75ft long by 35ft wide, an allowance of just over 6ft square each. Most of the prisoners were chained together in irons. The convicts were grouped into messes of six, with their rations calculated as being two thirds of the standard Royal Navy allowance. Accordingly, each mess should have received a weekly provision of: 16lb of bread, 12lb of flour, 14lb of beef, 8lb of pork, 12 pints of pease, 1½lb of butter and 2lb of rice. Whether they received anything like this appears doubtful. As well as the excessive confinement, malnourishment was a major cause of the fatalities. The contractors, Messrs. Calvert, Camden and King of London, were paid £17 7s 6d per convict embarked, and supplying short rations was an easy option for boosting their profit margin.

Despite all the setbacks, order was gradually achieved and the colony became established, something which probably owed much to the remarkable personal qualities of Arthur Phillip. Life in Australia took its toll on Phillip, however, and ill health forced him to return home in 1792. Despite his departure, the colony continued to develop and, from 1796, the growth of the community outside the prison was helped by a programme of assisted emigration for free settlers who were given a free passage, a grant of land and eighteen months’ free rations.

EVOLUTION OF AUSTRALIAN TRANSPORTATION

In the early years of Australian transportation, convicts could either serve out their sentence in the penal colony, join a labour gang on a public works project or be assigned to work for a free settler who might be anything from a government officer to a farmer or even a freed former prisoner. Assigned convicts typically worked as shepherds, cowherds, field labourers, domestic servants or mechanics, with their masters required to provide food, clothing and shelter. However, the conditions experienced by convicts under the assignment system could vary enormously. In 1838, the British parliament received a report on how convicts were treated:

An assigned convict is entitled to a fixed amount of food and clothing, consisting, in New South Wales, of 12lbs. of wheat, or of an equivalent in flour and maize meal, 7lbs. of mutton or beef, or 4½lbs. of salt pork, 2oz of salt, and 2oz of soap weekly; two frocks or jackets, three shirts, two pair of trousers, three pair of shoes, and a hat or cap, annually. Each man is likewise supplied with one good blanket, and a palliasse or wool mattress, which are considered the property of the master. Any articles, which the master may supply beyond these, are voluntary indulgences.108

Some contributors to the report likened the convict’s lot to that of a slave, with harsh punishments for any misdemeanour. The law in New South Wales enabled a magistrate to inflict fifty lashes on a convict for ‘drunkenness, disobedience of orders, neglect of work, absconding, abusive language to his master or overseer, or any other disorderly or dishonest conduct’. Alternative punishments for these offences included imprisonment, solitary confinement and labour in irons on the roads.

From 1840, a new stage-based probationary system was introduced where prisoners’ conditions and privileges and progression through the system were determined by their behaviour. In most cases, transportees began their sentence with an eighteen-month period of detention in a British prison. Stage 1 for ‘lifers’ was then hard labour on Norfolk Island. Stage 2 for lifers (Stage 1 for non-lifers) was working in labour gang in an unpopulated area on the mainland. Advancement to Stage 3 allowed paid work for private employer, while Stage 4 provided for release on licence. Finally, Stage 5 bestowed a conditional or absolute pardon.

As well as Port Jackson, a number of other prison colonies were subsequently set up, including ones at Hobart in Van Diemen’s Land (renamed Tasmania in 1856), Moreton Bay in Queensland, Port Phillip in Victoria, Swan River in Western Australia and on tiny Norfolk Island, 1,000 miles to the east of the mainland. In 1824, a former transport ship, the Phoenix, was anchored in Sydney Harbour to hold British convicts in transit to the other land-based penal settlements.

THE END OF TRANSPORTATION

Despite its great size, there were only so many convicts that Australia was prepared to receive. New South Wales closed its doors to the convict ships after 1840, and by 1846 Van Diemen’s Land was so overcrowded that transportation there was suspended for two years, finally being halted in 1852. Western Australia continued to accept convicts up until 1867.

As the number of destinations dwindled, the British courts gradually moved away from the use of transportation. In its place, increasing use was made of sentences combining a period of confinement followed by several years of labour at a public-works prison, such as the one at Portland, which opened in 1848.

Transportation finally ended on 9 January 1868, when the last convict ship, the Hougoumont, embarked 280 prisoners at Freemantle in Western Australia. Over the preceding eighty years, around 160,000 British convicts had been landed on Australian shores. Despite the hardships they often endured while serving out their sentences, many went on to become permanent settlers in the country. 109

THE FATE OF THE BRITISH HULKS

The re-establishment of transportation in 1787 did not result in the elimination of the prison hulks, which continued in operation for almost as long as transportation itself. The hulks were initially retained to provide temporary accommodation for transportees awaiting a place on an Australian sailing. Some prisoners, though, such as those who proved unfit to make the voyage, ended up serving the whole of their sentence on the hulks.

In 1802, management of the hulks passed from private contractors to the first Inspector of the Hulks, Aaron Graham. Graham issued new orders for improvements in the domestic routine and hygiene aboard the vessels and in the record-keeping. Officers were no longer to keep pigs or poultry on board for selling meat or eggs to the prisoners. The convicts’ daily food allowance was increased, with ‘coarse, wholesome meat’ now replacing the much-hated ‘ox-cheek’. The table below shows the new rations for each mess of six:

|

BREAKFAST |

DINNER |

SUPPER |

|||||

Barley |

Oatmeal |

Bread |

Beef |

Cheese |

Beer |

Barley |

Oatmeal |

|

lbs oz |

lbs oz |

lbs oz |

lbs oz |

lbs oz |

½ Pints |

lbs oz |

lbs oz |

|

Sunday |

1 4 |

0 4 |

7 14 |

5 14½ |

- - |

18 |

1 1½ |

0 6½ |

Monday |

1 4 |

0 4 |

7 14 |

- - |

2 10 |

18 |

- - |

1 8 |

Tuesday |

1 4 |

0 4 |

7 14 |

5 14½ |

- - |

18 |

1 1½ |

0 6½ |

Wednesday |

1 4 |

0 4 |

7 14 |

- - |

2 10 |

18 |

- - |

1 8 |

Thursday |

1 4 |

0 4 |

7 14 |

5 14½ |

- - |

18 |

1 1½ |

0 6½ |

Friday |

1 4 |

0 4 |

7 14 |

- - |

2 10 |

18 |

- - |

1 8 |

Saturday |

1 4 |

0 4 |

7 14 |

5 14½ |

- - |

18 |

1 1½ |

0 6½ |

Each Mess per Week |

8 12 |

1 12 |

55 2 |

23 10 |

7 14 |

126 |

4 6 |

6 2 |

|

4 6 |

6 2 |

|

The Bread to be of the Quality served to His Majesty’s Troops of the Line. |

||||

13 2 |

7 14 |

|

||||||

Each Man per Week |

2 3 |

1 5 |

9 3 |

3 15 |

1 5 |

21 |

||

Each Man per Day |

0 5 |

0 3 |

1 5 |

0 9 |

0 3 |

3 |

||

A Select Committee in 1810–11 noted that the cost of feeding each convict amounted to 13¼d a day, compared to the 9d a day expended at gaols such as Southwell and Gloucester. It was proposed that savings should be made by renegotiating the contracts for supplying the hulks’ food. The committee also looked at the widely varying daily allowances that the convicts received from their employers while working ashore. At the Woolwich Ordnance department, the men received beer and biscuit ranging in value from 2d to 4½d; at Portsmouth Dockyard, the daily allowance was small beer and biscuit to the value of 2¼d, with smokers receiving ½d worth of tobacco on top; at the Portsmouth Ordnance Department, the allowance amounted to 1d per day, while at the Sheerness Dockyard, no allowances were given at all. The committee proposed that some parity be established.

The committee’s report portrayed the prisoners’ quarters as dens of ‘gambling, swearing, and every kind of vicious conversation’. The counterfeiting of coins also went on. It appeared that night-time visual supervision of the men below decks was non-existent. In fact, it seemed ‘doubtful whether, in some of the Hulks at least, an officer could go down among the prisoners at night without the risk of personal injury’.110 After consultation with the Navy Board, a new plan was devised for subdividing the convicts’ quarters into a number of separate cells off a central corridor, although it took until 1817 for all the vessels to be fitted out in this way.

A regular concern about the hulks was the occurrence of sodomy and rape, which were said to be commonplace. George Lee, a convict on the Portland in Langstone Harbour in 1803 claimed that ‘the horrible crime of sodomy rages … shamefully throughout’. According to Jeremy Bentham, new inmates on the Woolwich hulks were routinely raped as a matter of course: ‘an initiation of this sort stands in the place of garnish and is exacted with equal rigour.’111 The 1810 Select Committee, in a circumspectly worded appraisal of such claims, were happy, however, to accept that ‘the Captains of the different Hulks all concur in disbelieving the existence among them of the more atrocious vice, which rumour has sometimes imputed to them’. Such activities, they believed, would be viewed as abhorrent by the other convicts and dealt with accordingly.112

Aaron Graham’s successor, John Capper, held the post of what became the Superintendent of the Hulks from 1815 to 1847. Capper’s main contribution in the early years of his tenure was the introduction of a scheme whereby convicts were classified as ‘Very Good’, ‘Good’, ‘Indifferent’, ‘Suspicious’, ‘Bad’ or ‘Very Bad’. Prisoners of each class were housed in separate areas of the ship so that, for example, docile inmates would not be bullied by aggressive ones. The classification was subsequently extended to separate youthful offenders from adults, with a separate hulk, the Bellerophon, allocated for boy convicts in 1824.

Further parliamentary appraisals of the hulks took place in 1828, 1831 and 1835. Despite repeated concerns about the convicts’ work being too lenient and the discipline too lax, little changed. The 1831 review by the Committee on Secondary Punishments heard from a former convict identified as ‘A.B.’ who, from the age of 17, had spent four years on the hulk Retribution at Sheerness. A.B. recounted that the convicts worked, slept and ate in irons weighing up to 4lb. The work they were given – pulling down buildings and unloading ships – often resulted in serious injury. Anyone judged to be shirking had his pay stopped and was placed in double-irons. The captain used only a fraction of the money officially allocated for buying the prisoners’ rations, but always kept a small quantity of top quality bread and meat to hand so that he could demonstrate to any visitors how well the men dined. Unfortunately, A.B. lost any sympathy he had gained when he revealed what went on below decks. New arrivals were routinely robbed of any valuables. Singing, dancing, fighting and gambling regularly took place. Newspapers, ‘improper’ books and quantities of spirits (smuggled inside a bladder) found their way on board. Some inmates operated small businesses selling tea, bread, tobacco and groceries to the other prisoners. A convict could receive visitors during the daytime, on which occasions he was excused from work. All in all, it was – as A.B. happily admitted – ‘a jolly life’. Shocked at such revelations, the committee recommended a clampdown on such indulgences and an increase in the convicts’ daily hours of work. 113

The convict ship Discovery was moored at Woolwich and Deptford between 1824 and 1830. She could house up to 200 convicts.

A lull in parliamentary concern about the hulks ended abruptly on 28 January 1847, when Thomas Dunscombe, MP, addressed the Commons on the appalling conditions that he claimed existed on the Woolwich hulks. Based on information he had been sent by William Brown, a convict nurse on the hulk Warrior, Dunscombe recited a catalogue of cases of inmates who had been mistreated or neglected by the ship’s surgeon Peter Bossey. One, a lunatic named George Monk, suffering from a broken leg, had been ‘allowed to lie in bed in his own water and filth until such time as a large piece fell out, putrid with his urine, from the bottom of his back bone’. At times, Monk had also been handcuffed to his bed or strait-jacketed. Another man, Peter Bailey, near to death, had requested the attendance of a Wesleyan Methodist minister but had been refused by Bossey, who had laughed at him and told him that he would die in the bed where he lay. Bailey died a few days later. A prisoner named Henry Driver, labelled as a ‘schemer’ by Bossey, died a few days after arriving at the Warrior. While the body was still warm, its entrails had been removed and thrown in the river.

An investigation by prison inspector Captain William John Williams found that most of William Brown’s specific claims were untrue or much exaggerated, but that the hulks suffered from lax management. A lack of regular inspection had resulted in two of the vessels, the Justitia and the hospital ship Unité, being filthy and infested with vermin. There had been an excessive use of corporal punishment, particularly on mentally disturbed prisoners, with the birch and cat o’ nine tails. An inadequate diet, much of which was regularly thrown overboard by the prisoners, had led to a high rate of scurvy. Amongst Williams’ recommendations were an improvement to the diet – cocoa should be served instead of gruel at least once a day, white bread instead of brown two or three times a week, and 6oz of pork instead of cheese. Each prisoner should also receive an extra daily allowance of 12oz of potatoes.114

From 1849, overall management of the remaining hulks moved to a new body, the Directors of Convict Prisons. However, the increasing use of land-based prisons saw the hulk fleet continue to shrink until, by 1857, only two vessels remained – the Defence, whose inmates were mostly invalids, and the hospital ship Unité. On 14 July 1857, a fire broke out in the Defence’s coal store. Within a few weeks, both vessels had been abandoned and most of their inmates transferred to an old war prison at Lewes in Sussex. So ended the eighty-year-long ‘temporary’ measure for holding convicts in floating prisons on the Thames.

A convict ward set for dinner aboard the hulk Defence in the 1850s.

The death of a convict on the hulk Justitia – attributed to the illustrator George Cruickshank. After severe criticism of conditions aboard the Justitia in 1847, and a cholera outbreak the following year, the vessel was condemned and replaced by the newly refitted Defence.