seven

Prisoners of War

The endless succession of wars in which England was involved up until the twentieth century regularly resulted in the capture of prisoners – men who then had to be housed somewhere. Because such prisoners only needed to be accommodated until an exchange was arranged or until the conflict ended, the facilities they needed were fairly basic – food, somewhere to sleep and medical care. At times, however, the sheer numbers of war prisoners caused problems. In 1763, following the Seven Years War, around 40,000 Frenchmen were being held in improvised prisons, while half a century later, at the end of the Napoleonic Wars, more than 120,000 were held captive. Over a similar period, the number of civilian prisoners rose from a mere 4,000 to around 16,000. 115 Conflicts with America, Spain and Holland during the 1770s and 1780s also swelled the volume of war prisoners being held.

Over the years, the accommodation provided for prisoners of war took several different forms. A floating hulk, the Cornwall, was used for French prisoners of war from 1755, with up to sixty others later established at Portland and Plymouth. On the Brunswick, moored off Chatham, 460 prisoners were crowded at night into a deck measuring 125ft by 40ft, with a ceiling only 4ft 10in high.116

Existing buildings were also pressed into service such as the castles at Edinburgh and Portchester. In 1756, Sissinghurst Castle was leased to the government for use as a prison. Over the following seven years, 3,000 French prisoners were held there in cold and overcrowded conditions that were terrible for prisoners and guards alike. Much of the house and furniture were destroyed by the inmates and used for firewood. In 1779, a new prison was opened at Stapleton in Bristol to hold naval prisoners of war who were being landed at Bristol – by 1782 it housed almost 800 Spaniards and Dutchmen. In 1783, a former orphans’ home at Shrewsbury was converted to house up to 600 Dutch prisoners.117 A camp for French and Dutch soldiers and sailors was built in 1796 at Norman Cross, near Peterborough. From 1796 to 1816, it held about 10,000 prisoners, of whom at least 1,700 died.

THE KING’S HOUSE, WINCHESTER

Between 1778 and 1780, the King’s House at Winchester was home to over 6,000 French and 1,500 Spanish prisoners. The house, designed by Sir Christopher Wren, was originally intended to be a palatial residence for Charles II, but the scheme had never been completed due to lack of money.

Following the outbreak of a ‘distemper’ amongst French prisoners in April 1779, and another amongst the Spanish in April 1780, a parliamentary committee investigated the conditions at Winchester and its medical facilities. A list of complaints from the Spanish inmates had blamed the outbreak on the prison’s poor quality bread which was described as ‘not even fit for dogs’. The committee, on the other hand, concluded that the disease, ‘a contagious malignant fever of the gaol kind’, had probably been brought ashore by the sailors themselves and its spread owed much to their own ‘indolence and want of cleanliness’.118 Increased space for the prison hospital, improvements in the prison’s ventilation and hygiene, with regular bathing of the inmates, airing of their hammocks and bedding, and a twice-weekly fumigation of the rooms with sulphur, had now dealt with the problem. A change in the sick dietary was also instituted. The standard and sick diets at Winchester are shown below:

Days |

Beer |

Bread |

Beef |

Butter |

Cheese |

Peas* |

Salt |

|

Quarts |

Pounds |

Pounds |

Ounces |

Ounces |

Pints |

Ounces |

Sunday |

1 |

1½ |

¾ |

— |

— |

½ |

⅓ |

Monday |

1 |

1½ |

¾ |

— |

— |

— |

⅓ |

Tuesday |

1 |

1½ |

¾ |

— |

— |

½ |

⅓ |

Wednesday |

1 |

1½ |

¾ |

— |

— |

— |

⅓ |

Thursday |

1 |

1½ |

¾ |

— |

— |

½ |

⅓ |

Friday |

1 |

1½ |

¾ |

— |

— |

— |

⅓ |

Saturday |

1 |

1½ |

¾ |

4 or |

6 |

½ |

⅓ |

Total |

7 |

10½ |

4½ |

4 |

6 |

2 |

2⅓ |

*Or a pound of good cabbage. |

|||||||

Scheme of diet for the Prisoners in the Hospital. |

|

Low |

Water Gruel, Panada, Rice Gruel, Milk Pottage or Broth, 8oz of Bread (and if Butter is ordered, 2oz.) —For Drink, Toast and Water, Ptisan, or White Decoction. |

Half |

For Breakfast, Milk Pottage. For Dinner, 8oz of Mutton, some light Bread Pudding, or in lieu of it some Greens, a Pint of Broth, a Pound of Bread, and Three Pints of Small Beer. |

Full |

Breakfast as above.—For Dinner, One Pound of Meat, One Pint of Broth, One Pound of Bread, and Two Quarts of Small Beer. Supper in the Two last-mentioned Diets to be of the Broth left at Dinner, or, if thought necessary, to be of Milk Pottage. |

Rice Milk, Orange Whey, Orange and Lemon Water, Tamarind Whey,Vinegar Whey, Balm and Sage Tea, to be discretionally used by the Surgeon. Besides the Cordial Medicines of the Dispensary, Wine is always allowed for such sick Prisoners as the Surgeon judges it to be proper for. |

|

Panada, included in the hospital’s low diet, was made from bread boiled to a pulp in water and sometimes flavoured with sugar, nutmeg, currants or other ingredients. The following recipe for panada ‘for a sick or weak stomach’ was provided by Richard Bradley in the 1762 edition of The Country Housewife:

Ptisan (many alternative spellings include tisane, thisan, petisane etc.) was a medicinal drink of which barley water was the most common form. Here is Hannah Glasse’s recipe from 1758:

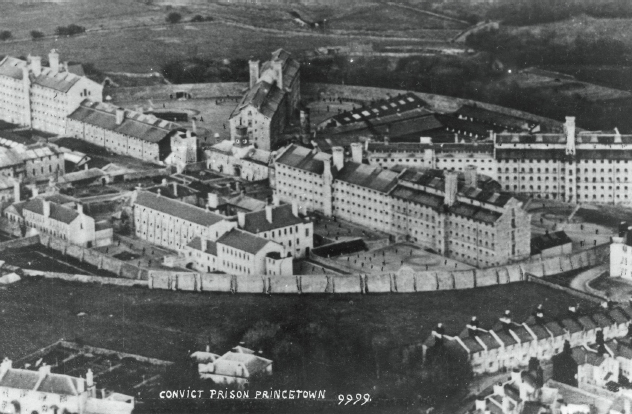

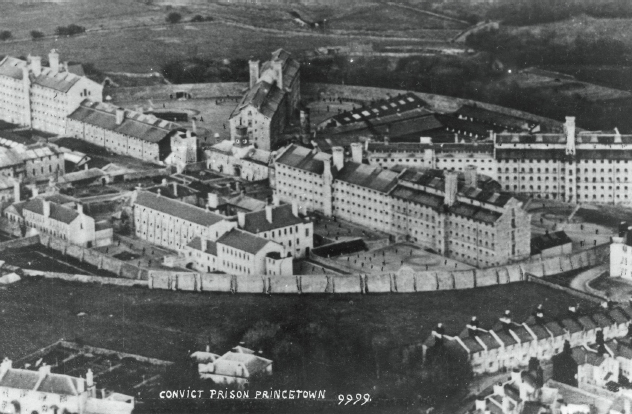

DARTMOOR

Overcrowding at the Stapleton and Norman Cross prisons and aboard the hulks at Plymouth resulted in the building of a large new prison at Princetown on Dartmoor. The site chosen was near to granite quarries which supplied stone for construction of the prison. Within a few months of its opening in May 1809, it housed 5,000 French prisoners. A subsequent extension was used to hold captives from the Anglo-American war of 1812–5.

The prison’s distinctive layout, reflecting the popular radial designs of the day, comprised five large rectangular blocks arranged around a semi-circle, like the spokes of a wheel. Each block, two storeys high, could house 1,500 men, sleeping in two tiers of hammocks. At the central hub, an open space was used as a daily market place where local people could sell vegetables and other wares. Other buildings included a large hospital and an officers’ block. The site was surrounded by two walls with a road in between where guards patrolled.

At its height, the prison held over 8,000 inmates whose diet was rather better than that received by many of the prisoners in England’s civilian gaols. The daily ration for Dartmoor’s healthy prisoners is shown below:121

Sunday |

One pound and a half of bread. Half a pound of fresh beef. Half a pound of cabbage or turnips fit for the copper. One ounce of Scotch barley. One-third of an ounce of salt. One-quarter of an ounce of onions. |

Wednesday |

One pound and a half of bread. One pound of good sound herrings (red herrings and white pickled herrings to be issued alternately). One pound of good sound potatoes. |

Friday |

One pound and a half of bread. One pound of good sound dry cod fish. One pound of good sound potatoes. |

The food was provided by private contractors and its quality was specified in some detail:

Three different levels of diet were provided for prisoners of war who were sick, with plenty of greens – and beer – for the less seriously ill:

Patients on Low Diet |

A pint of tea in the morning for breakfast, and a like quantity in the evening, 8oz bread, 2oz butter, or in lieu of butter, 1 pint milk, ½ pint broth, or such an additional quantity thereof as the surgeon shall judge proper. For drink, barley-water, toast and water, water-gruel, lemon-water, vinegar-whey, balm or sage-tea. In febrile cases the barley-water may be acidulated with lemon juice. |

Patients on Half Diet |

Tea morning and evening as above, 16oz bread, 8oz beef or mutton, 8oz greens, or good sound potatoes, 1 pint broth, and 3 pints small beer. For common drink, barley-water. |

Patients on Full Diet |

Tea morning and evening as above, 16oz bread, 16oz beef or mutton, 1 pint broth, 16oz greens or good sound potatoes, and 2 quarts small beer. For common drink, barley-water. |

In ‘particular cases of debility, or where the appetite may be capricious’:

The surgeon may substitute fish, fowl, veal, lamb, or eggs, provided the expense incurred for the same do not exceed the price of the beef or mutton allowed. One dram and a half of good souchong tea, seven drams of good muscovado sugar, and one sixth part of a pint of genuine milk, to be allowed to every pint of tea. The broth to be made by boiling together the meat allowed in the half and full diet, with the addition of twelve drains of good sound barley, twelve drains of good onions, or one ounce of leeks, and three drains of parsley for every pound of meat.

Again, the quality of the items was carefully stipulated:

Despite the relatively good fare provided to the Dartmoor inmates, food was still the cause of problems, particularly amongst a group of French prisoners known as the ‘Romans’. These were men who, largely because of the gambling that was rife in the prison, had literally lost their shirts – together with their bedding and any other possessions. Such men formed a commune in the large lofts beneath the prison roofs which had been intended to provide exercise space during bad weather. The Romans rarely tasted the prison’s official dietary:

From morning till night groups of Romans were to be seen raking the garbage heaps for scraps of offal, potato peelings, rotten turnips, and fish heads, for though they drew their ration of soup at mid-day, they were always famishing, partly because the ration itself was insufficient, partly because they exchanged their rations with the infamous provision-buyers for tobacco with which they gambled. In the alleys between the tiers of hammocks on the floors below you might always see some of them lurking, if a man were peeling a potato a dozen of these wretches would be round him in a moment to beg for the peel; they would form a ring round every mess bucket, like hungry dogs, watching the eaters in the hope that one would throw away a morsel of gristle, and fighting over every bone.122

After the prison’s own bakehouse was burned down in October 1812, the prisoners refused to accept the bread sent in from Plymouth by the contractor, claiming that it was damp and sour. After satisfying himself that the bread was of good quality, the prison’s chief officer Captain Cotgrave announced that any man who refused the bread would forfeit the ration for that day. According to one account, the starving Romans:

Fell upon the offal heaps as usual, and when the two-horse waggon came in to remove the filth they resented the removal of their larder. In the course of the dispute, partly to revenge themselves upon the driver, partly to appease their famishing bloodthirst, these wretches fell upon the horses with knives, stabbed them to death, and fastened their teeth in the bleeding carcases. This horror was too much for the stomachs of the other prisoners, who helped to drive them off.123

A rather more salubrious part of the premises, known as the Petty Officers’ prison, housed French naval and merchant service officers. Many were fairly well-to-do men who were able to buy provisions from the daily market and also hire prisoners from other sections to perform menial tasks such as cleaning for them. Even here, though, life was not uneventful:

One day at dinner a man pulled out of the soup bucket of his mess a dead rat which he held up by the tail, whereupon heads and tails and feet were dredged up from every bucket in such numbers that they would have furnished limbs for fully a hundred animals. We may judge whether the regulation diet of the prisoners was sufficient, from the fact that out of all these Frenchmen of the middle classes only a handful of the most squeamish went without their soup that day. For a time the life of the cooks hung by a thread, and it was only upon the intervention of the Commissaire that the head cook was allowed to speak in his own defence. The coppers, as it seemed, had been filled with water overnight as usual, but through forgetfulness the covers had not been closed, and the coppers had thus been converted into rat traps. It had not occurred to the cooks to dredge them for dead bodies, and the meat and vegetables had been thrown in atop and the fires lighted. 124

Naturally enough, some foreign prisoners attempted to recreate their home cuisine. Some of the more enterprising French inmates ‘opened booths for the sale of strange and wonderful dishes compounded of the Government rations with ingredients purchased in the market. The favourite was a ragout, called “ratatouille,” made of Government beef, potatoes and peas.’125 When American prisoners came to Dartmoor, some shaved a thin layer from the crust of their bread which was then scorched over coals to make a form of coffee.

An aerial view of Dartmoor prison. After 1815, Dartmoor was unoccupied until 1850 when it was re-opened as a public works prison. Within a few years it was mainly being used as an invalid prison and by 1858 housed up to 1,200 convicts capable of performing light labour.