eight

The Evolution of Prisons 1780s – 1860s

PENITENTIARY HOUSES

As an alternative to transportation, the 1779 Transportation Act had sanctioned the building of two large ‘penitentiary houses’, one for men and one for women, near to the capital. The Act went into considerable detail about the operation of the proposed houses. As well as the prisoners’ own quarters, the buildings were to include stores, workshops, an infirmary, a chapel, burying-ground and ‘dark but airy dungeons’. New arrivals would be washed, issued with a distinctive prison uniform and given a medical examination. For up to ten hours a day, Sundays excepted, prisoners would be put to ‘Labour of the hardest and most servile Kind, in which Drudgery is chiefly required … such as treading in a Wheel, or drawing in a Capstern, for turning a Mill or other Machine or Engine, sawing Stone, polishing Marble, beating Hemp, rasping Logwood, chopping Rags, making Cordage’. Work suggested for the less able included picking oakum, weaving sacks, spinning yarn and knitting nets. A small part of any profit from such work could be used by the prisoner or their family. The inmates were to sleep in individual cells, each measuring at least 7ft by 10ft by 9ft high, and heated by flues from the prison fires. Association between the prisoners would be confined to work hours, meal times, exercise periods and during twice-daily chapel services. The prison diet would consist of ‘Bread, and any coarse Meat, or other inferior Food, and Water, or small Beer’. However, each prison was also to have a kitchen garden. Finally, prisoners were to be divided into three categories known as First, Second, or Third Class, through which they would automatically progress during each third of their sentence. First Class prisoners would receive the most severe treatment and Third Class the most lenient.

Implementation of the proposals was placed in the hands of a supervisory committee whose initial membership included John Howard. However, despite their efforts to get the project off the ground, the scheme ground to a halt.

LOCAL PRISONS

The 1780s and 1790s did, however, see a burst of activity in the modernisation of local prisons, with more than sixty rebuilt during this period, many the work of architect William Blackburn, a disciple of John Howard.126 Although a wide variety of designs were constructed, the buildings typically included separate sections for different classes of prisoner, individual sleeping cells, work-rooms, exercise yards, a chapel, laundry and infirmary. Cells opened onto a linking corridor or walkway placed either on the inside or the outside of the building.

The simplest type of plan, used at county gaols such as Exeter and Winchester, was a single block with the keeper’s quarters placed at the centre. Courtyard designs, such as those in new county gaols at Hertford and Moulsham, were based on the layout of monastic cloisters and placed wings around the sides of a quadrangle. What were to prove more significant were Blackburn’s polygonal and radial designs. An example of the first of these was the new gaol erected at Northleach in the late 1780s. The cell block formed five of the sides of an octagon, providing good visibility of all the cells from a central point. The radial design, where a number of wings emanated from a central hub, was used at the new county gaol in Ipswich. The radial principle was widely adopted in Victorian workhouses and prisons, although Blackburn’s designs lacked the internal open galleries that characterised many later prison buildings.127

BENTHAM’S PANOPTICON

While the national penitentiary scheme was languishing, some alternative proposals were put forward by philosopher and social reformer Jeremy Bentham. One idea was for a set of colour-coded institutions – a white-walled building for debtors and those awaiting trial, a grey one for short-term prisoners and a black one for those serving life sentences. Outside the latter two would stand the figures of ‘a monkey, a fox and a tiger, representing mischief, cunning, and rapacity, the source of all crimes’; inside, two skeletons would flank an iron door.128

A later scheme, the ‘panopticon’ or inspection house, was based on a design for a workshop by Bentham’s brother Samuel. It consisted of a circular or polygonal building with cells on each storey and, at the centre, an inspection ‘lodge’ from where prisoners could be supervised. The establishment would be managed by a contractor who would provide profitable work from which the inmates would receive some income. The contractor would be penalised for any prisoners who died or escaped while in his custody. Bentham’s plans included a glass roof and mirrors to aid observation of the inmates, a complex system of pipes for ventilation and heating and a network of ‘conversation tubes’ allowing staff or visitors to speak to prisoners from the central lodge.

Bentham’s vigorous and persistent lobbying of ministers eventually resulted in some modest backing for a panopticon prison and in 1799 he acquired a site for its construction on the north bank of the Thames at Millbank. However, like the original penitentiary houses project, the scheme never gained sufficient momentum and was effectively abandoned by the government in 1803. Panopticon-style buildings were later erected in other countries, including the Koepelgevangenis at Haarlem in Holland, the Presidio Modelo in Cuba and the Stateville Correctional Center in the USA.

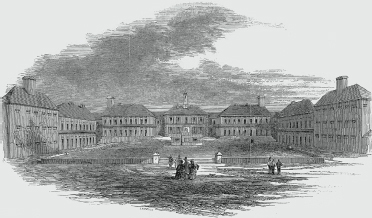

MILLBANK

In 1810, more than thirty years after its conception, the plan to build a new, large, national penitentiary was revived. A parliamentary Select Committee was set up and took evidence from a number of leading figures. Sir George Onesiphorus Paul, another devotee of John Howard, who had transformed the county prisons in Gloucestershire, described his use of a ‘stage’ system in which the first third of a prisoner’s sentence was spent in solitude. The Rev. John Becher gave details of the ‘association’ system used at the Southwell House of Correction where groups of inmates were encouraged to work by receiving a share of the profits from their labour. The committee also heard the views of Jeremy Bentham who was still eager to promote the virtues of his panopticon, but he was effectively sidelined from the project.

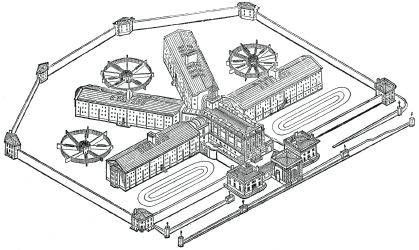

A bird’s-eye view of the Millbank prison. Occupants of the present-day site include the Tate Gallery and the headquarters of the Prison Service.

The committee decided to recommend construction of a single, large prison for up to 600 convicts – a figure later increased to 1,000. A competition for its design took place, the winning plan being submitted by William Williams. The construction work, initially expected to cost in the order of £300,000, began in 1812 at Bentham’s own Millbank site. For the land and for all his trouble, Bentham received compensation to the tune of £23,000. Problems with the marshy ground delayed the opening of the prison until 1816 and building was not finally completed until 1821, by which time the cost had risen to the then huge sum of £450,000.129

Millbank’s novel design revolved around a central hexagon which housed the governor, matron, steward, surgeon, chaplain, master manufacturer and the bakery. Each of the hexagon’s six sides then formed the inner edge of a three-storey pentagonal cell block. The area within each cell block was divided into five airing yards with a tall watch-tower at the centre. Each of the cell blocks was, in effect, a miniature panopticon.

Despite an optimistic start, including a visit by the Duchess of York in 1817, Millbank was beset by problems. The sheer size of the building, its circular layout and the labyrinth of winding staircases, dark passages, and innumerable doors and gates proved totally confusing. One old warder, even after several years at the prison, still carried a piece of chalk to help him mark his way around.130 There were also regular disturbances and even riots. One particularly embarrassing incident took place in April 1818 during a Sunday morning service in the chapel at which the Chancellor of the Exchequer was present. Discontent about recent problems with the prison’s bread came to head with male inmates banging the flaps on their seats and throwing loaves around. Some of the women began chants of ‘Give us our daily bread’ and ‘Better bread!’ while others began screaming or fainting, and eventually were all escorted from the room. Further unrest was only quelled with the help of the Bow Street Runners.131

The regime at Millbank combined those in use in the gaols at Gloucester and Southwell. Those prisoners serving the first half of their sentence (known as First Class inmates) worked and slept in the seclusion of their individual cells. Those in the second half of their sentence (the Second Class) performed their labour in groups. Complete isolation of the First Class inmates proved to be impossible, however – staff were unable to prevent them communicating when they were attending chapel, taking exercise or working a shift on the prison’s corn mills or water pumps. It was soon concluded that any beneficial effects of the First Class were rapidly undone in the Second so, from 1832, inmates spent the whole of their sentence in solitude. Even that proved ineffective. Each cell had two doors, an inner one of bars and an outer one of wood. Because of the building’s poor ventilation, the outer doors were left open during the day – allowing prisoners in adjacent cells to talk to one another.

New arrivals at the prison were given a haircut, bath and medical examination. Their own clothes were either sold or, if ‘foul or unfit to be preserved’, burned. The prison uniform, slightly different for the two classes, was decreed to be made of cheap and coarse materials, and distinctively marked so as to identify escapees. The wearing of a black armband (or ribbon for women) was permitted following the death of a near relation.

The prisoners’ daily routine comprised ten sections, each signalled by the ringing of a bell:

Bell |

Time |

Activity |

1 |

5.30 (or daybreak in winter) |

Rise, dress, comb hair, visit washroom under supervision of Turnkey. |

2 |

6.00 |

Begin work. |

3 |

8.30 |

Prisoners appointed Wardsmen/Wardswomen collect porridge or gruel from kitchens for distribution to other inmates. |

4 |

9.00 |

Eat breakfast. |

5 |

9.30 |

Resume work. |

6 |

12.30 |

Wardsmen/Wardswomen collect dinners. |

7 |

13.00 |

Eat dinner and take air or exercise. |

8 |

14.00 |

Resume work. |

9 |

18.00 (or sunset in winter) |

Finish work. |

10 |

18.00 (or 19.00 in winter) |

Return to cell for night. Gruel or porridge delivered to cell. |

Establishing what was eventually to become normal prison practice, all food for Millbank’s inmates was supplied by the institution. The prison’s 1817 dietary (below) also includes one of the first instances of porridge making its appearance as the standard prisoner’s breakfast fare:

DAILY, 1lb of Bread, made of whole Meal; and to serve the day. |

||

BREAKFAST |

|

1 pint of hot gruel or porridge. |

DINNER |

Sundays |

6oz of clods, stickings, or other coarse pieces of Beef (without bone, and after boiling) with ½ a pint of the Broth made there from 1lb of sound Potatoes, well boiled. |

Mondays |

1 quart of Broth, thickened with Scotch barley, rice, potatoes, or pease, with the addition of cabbages, turnips, or other cheap vegetables. |

|

SUPPER |

|

1 pint of hot gruel or porridge. |

N.B.—Prisoners may reserve such part of the provision previously delivered out for their Supper. Salt and Pepper as the Committee shall direct. The only Liquor allowed to prisoners in health (except broth, gruel or porridge) shall be Water. Prisoners confined to Bread and Water diet, for punishment, shall be allowed an addition of ½lb of Bread, instead of other provisions. Prisoners, employed in works of extraordinary labour, or under circumstances which may render it necessary, may be allowed an addition to the quantity of their provisions. |

||

The only variation in the dietary came on Christmas Day, when the meat was roasted (rather than boiled) and an additional 8oz of baked pudding was served. Prisoners who were ‘deficient in cleanliness’ were liable to have their meat and vegetables withheld. More serious offences could be punished by a diet of bread and water and/or confinement in a dark cell for up to a month.

In 1822, Millbank’s Medical Superintendent, Dr Copland Hutchinson, concluded that the Millbank dietary was more liberal than that found in most other prisons. He persuaded the prison’s Committee of Management to adopt the new dietary shown below. The most significant change was in the midday dinner provision – the daily pound of potatoes and four-times-a-week ration of meat had gone and in its place was an unchanging portion of soup.

MORNING |

Males |

12oz of Bread, and 1 pint of Gruel |

Females |

9oz of Bread, and ¾ pint of Gruel |

|

NOON |

Males |

12oz of Bread, and 1 pint of Soup |

Females |

9oz of Bread, and ¾ pint of Soup |

|

EVENING |

Males |

1 pint of Soup |

Females |

¾ pint of Soup |

|

The Soup to be made with Ox heads, in lieu of other meat, in the proportion of one Ox head for about 100 Male prisoners, and the same for about 120 Female prisoners; and to be thickened with Vegetables and Pease, or Barley alternately, either weekly or daily, as may be found most convenient. |

||

Within a few months, the health of the prisoners was in serious decline. They became pale, languid, thin, feeble and unable to perform their usual labour. There were also numerous cases of diarrhoea and dysentery. More than half the inmates were affected, females more than males, and those in the Second Class more than those in the First. One group of prisoners who were almost entirely unscathed were those who worked in the prison kitchens. Eventually, two outside physicians were called in and diagnosed the mysterious illness as a combination of infectious dysentery and ‘sea-scurvy’. Scurvy, whose symptoms included spongy and bleeding gums, results from a vitamin C deficiency but was then attributed to factors such as insufficient food, cold, damp, fatigue and sea air. An immediate change in the Millbank diet was ordered, with a daily allowance of 4oz of meat and 8oz of rice replacing the dinner-time soup, and white bread being provided instead of brown. Each prisoner was also given an orange at each meal. In the longer term, it was recommended that the amount of meat in the diet should be increased, that only good quality white bread be used, and that at least one meal a day should be given in solid form. The potato ration was not restored, however.

Although the change in the Millbank diet appeared to produce a rapid improvement in the prisoners’ health, there was then a widespread relapse. It was decided that the building itself was contributing to the problems and would have to be evacuated while the necessary changes were made. Four naval vessels at Woolwich were pressed into service as prison hulks, the Ethalion and Dromedary (housing 467 male convicts) and the Narcissus and Heroine (167 females). The transfer of Millbank’s residents began in August 1823 and the prison was closed for a year, during which time all the rooms were fumigated with chlorine and extensive improvements made to the ventilation and drainage. For the Millbank prisoners now on the hulks, conditions were often no less unpleasant than those they had left behind. The continuing level of sickness among the women in particular led to many of them being given free pardons, while some of the men were transferred to the fleet of regular hulks.

Despite the efforts to improve the running of Millbank, it continued to suffer from problems and a frequent turnover of governors. More seriously, it became increasingly clear that keeping prisoners separated over long periods was not without its consequences. In 1841, a disturbing increase in the numbers of inmates diagnosed as insane led to the initial period of separation being reduced to three months. Finally, in 1843, the Home Secretary, Sir James Graham, admitted that, as a penitentiary, Millbank had been an entire failure and it would become a short-term holding prison for those awaiting transportation.

THE SEPARATE AND SILENT SYSTEMS

During the 1830s, considerable debate took place about the relative merits of two systems of discipline, both of which had come into use at different prisons in America. The ‘silent’ system, developed at Auburn prison in New York State, allowed prisoners to associate during their daytime activities but not speak. The alternative ‘separate’ system, deployed at prisons such as Cherry Hill in Philadelphia, kept prisoners in isolation – work, exercise and mealtimes all took place in solitude. Opponents of the silent system criticised the corporal punishment that was invariably required to suppress communication and saw the separate system as one that fostered penitence and reformation. Opponents of the separate system saw it as depriving prisoners of natural human contact and, in purely practical terms, being more expensive to implement in terms of the accommodation and staff required.

Use of the separate system in England gained momentum following the 1835 Prisons Act, which increased central involvement in all the country’s prisons. Each prison’s rules were now required to be submitted for the Home Secretary’s approval, and inspectors were appointed to visit every prison at least once a year. The inspectors appointed for the ‘Home District’ were the Reverend Whitworth Russell (a former chaplain at Millbank) and William Crawford – both staunch supporters of the separate system. In the scheme they favoured, inmates would sleep, work and eat in a spacious and self-contained cell, with no contact allowed with other prisoners. The daily routine would include time for reflection, religious devotions, exercise and receiving regular visits from prison officers, particularly the chaplain.

Crawford and Russell produced a number of designs for model prisons in which their scheme could be implemented, with some of their plans being taken up by local prisons interested in introducing the separate system. This trend was given added impetus in the 1839 Prisons Act under which all new prison plans required approval from the central government in the shape of Joshua Jebb, the Home Office’s advisor and subsequently Surveyor General of Prisons. The Act effectively gave official endorsement to the separate system which, it insisted, was quite different from solitary confinement.

Crawford and Russell’s greatest success, however, came in 1838 when their proposal to erect a large model prison in London gained support from the Home Secretary, Lord Russell, who also just happened to be Whitworth Russell’s uncle.

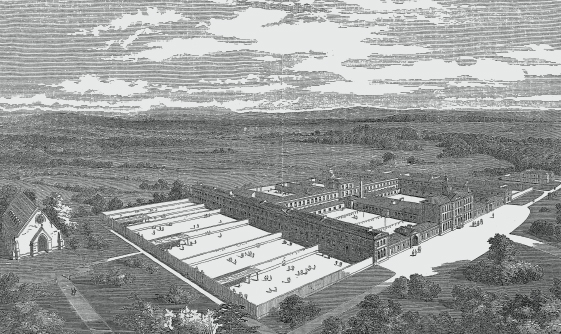

PENTONVILLE

The site chosen for the new ‘Model Prison, on the separate system’ was at Pentonville in north London. Construction began in April 1840, and the first inmates arrived in December 1842.

In addition to its role as a model prison, Pentonville’s function within the penal system was to provide an initial term, normally eighteen months, of probationary discipline and labour for selected convicts prior to their transportation to Van Diemen’s Land. Those behaving well would receive a ‘ticket-of-leave’, effectively freedom in their new country. Those performing indifferently would be given a probationary pass, a status which imposed some restrictions of their movement and earnings. For those whose conduct at Pentonville was deemed unsatisfactory, their destination would be a convict labour settlement.

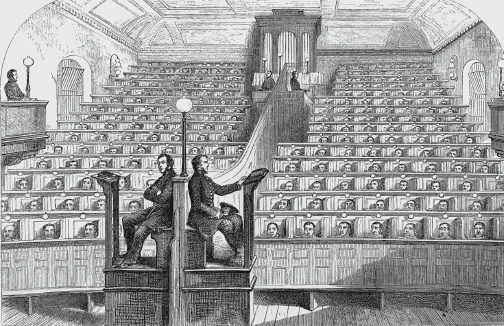

The architect of Pentonville was Joshua Jebb, but its design was clearly based on the ideas of Crawford and Russell. The main prison building comprised a central administration block from which four wings radiated like the spokes of a half-cartwheel. Each wing contained 130 cells arranged in three galleries, one above the other, with each floor containing forty or so individual cells. From the central hall it was possible for staff to have a view of every cell door. Inside each cell was an alarm handle which rang a bell and raised a semaphore indicator outside the cell’s sound-proof door.

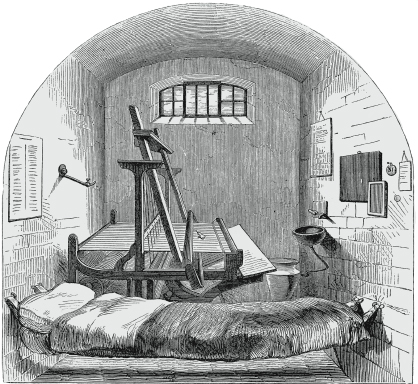

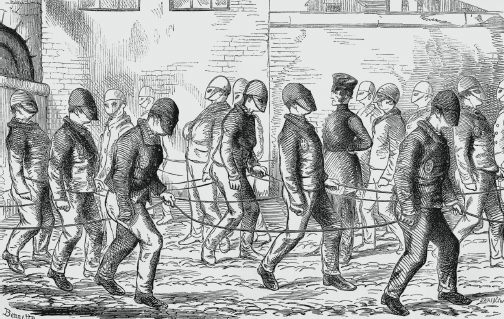

The regime imposed at Pentonville was a rigorous form of the separate system. Prisoners slept, worked and ate in their cells, only going outside for exercise or to attend chapel, at which times they wore turned-down caps (later masks) to conceal their faces. The circular exercise yards were divided into individual segments at the centre of which was an observation post. The chapel, too, was constructed with partitions between each seat to prevent communication.

An important aim of Pentonville was to equip each inmate with a trade by which they could earn their living in Australia. Instructors were employed for a variety of trades including carpentry, shoemaking, tailoring, rug and mat weaving, linen and cotton weaving, and basket making. Prisoners were also provided with twice-weekly classes which included reading, writing, arithmetic, history, geography, grammar and scripture. A Bible, prayer book and hymn book were given to every inmate able to use them.

A bird’s-eye view of Pentonville prison showing the prison buildings, segmented circular exercise yards and perimeter wall.

Pentonville cells, 13ft by 7ft by 9ft high, were fitted with a hammock, table and stool, and a copper wash-basin which drained into an earthenware lavatory. Each cell had a non-opening window high up in its wall, with ventilation and heating provided through a system of flues and gratings in the walls.

The individual high-sided pews in Pentonville’s prison chapel were intended to prevent inmates communicating during services. However, the governor’s report for 1852 noted seventy attempts to do so, plus a further six of ‘dancing in chapel, mimicking chaplain, and other misconduct during divine service’.

Convicts exercising at Pentonville in the 1850s. The masks prevented all communication, even by facial expression, and also prevented prisoners from recognising one another.

As at Millbank, the daily routine, from rising at 05.30 until lights out at 21.00, was timetabled with military precision. Parties of sixteen prisoners, in single file at 5-yard intervals, were marched from their cells for sessions of exercise, worship or labour – pumping water from the prison’s own 370ft deep artesian well. The warders’ activities were regulated by special clocks around the prison, with levers requiring to be pressed at preset times. Moving inmates from their cells to the chapel, for example, was to occupy exactly six and a half minutes.

The formulation of the dietary at Pentonville received special attention, with the prison’s medical officer, Dr Owen Rees, examining those in use at other prisons, on board the hulks and in hospitals and workhouses. He also weighed prisoners regularly to assess the adequacy of the food. His initial dietary, comprising bread, cocoa, gruel, five meat and potato dinners a week, and two cheese dinners, resulted in 62 per cent of the prisoners losing weight. Increasing the daily bread allowance from 16oz to 20oz reduced weight losses but still resulted in health problems such as ‘debility’. Restoring the bread to 16oz but serving meat and potato dinners every day still resulted in a modest but widespread weight loss. Upping the daily bread allowance to 20oz and the potato ration from ½lb to 1lb, at last gave an acceptable level of weight maintenance.132 The final dietary is shown below:

In November 1843, The Times reported that after barely six months at Pentonville, two inmates had been ‘driven mad by the severity and the seclusion of its discipline’, requiring their removal to the Bethlehem Hospital. It condemned the prison’s ‘maniac-making system’ which, it noted, subjected prisoners to solitude for a period six times as long as that which the Millbank authorities had now agreed was the safe maximum for such confinement.133 For the first few years of its life, the level of such problems was insufficient to cause the authorities serious concern. However, in 1848, the Pentonville Commissioners noted ‘the great number of cases of death and of insanity, as compared with that of former years’. 134

Ironically, it was not only the convicts who appeared to suffer ill effects from the new prison buildings. In 1847, Whitworth Russell committed suicide at Millbank. William Crawford died in the same year after collapsing during a meeting at Pentonville.135

CHANGES TO LOCAL PRISONS

A fresh impetus to the reform of local prisons came with the Gaol Fees Abolition Act of 1815, which decreed that ‘all Fees and Gratuities paid or payable by any Prisoner, on the Entrance, Commitment or Discharge, to or from Prison, shall absolutely cease, and the same are hereby abolished and determined’. 136 Responsibility for paying gaolers’ salaries now rested with local JPs with the money being provided from town or county rates.

In 1834, the Middlesex House of Correction at Coldbath Fields adopted the silent system where prisoners could work in association, but not communicate. Here, in the oakum room, the closely supervised inmates were required to pick apart 3½ pounds of old rope per day – a hook attached to the knee could assist in the task.

Sir Robert Peel’s Gaol Act of 1823 137 took the view that prisons should be ‘an object of terror’ but that those in prison should not become ‘worse members of society, or more hardened offenders’. The Act consolidated and reiterated a number of previous measures relating to hygiene and diet, the prevention of gambling and sale of alcohol, and the payment of prison staff through salaries rather than prisoners’ fees. The Act required separate accommodation to be provided for different categories of prisoner, such as debtors, felons and those awaiting trial. Males and females were to be housed separately and women were to be supervised only by female warders. Each prisoner was to have a hammock or bed provided, either in a cell of their own or sharing with at least two others. Those on hard labour were to work up to ten hours a day. Prisoners were to be provided with instruction in reading and writing. The Act also clarified the distinction between common gaols and houses of correction, with the latter to be used for all ‘idle and disorderly Persons, Rogues and Vagabonds, incorrigible Rogues and other Vagrants’. Prison keepers were to make quarterly reports to local JPs and, along with the chaplain and surgeon, keep regular journals. The Act’s main deficiency was that it applied only to the larger locally administered prisons, less than half of those in operation, and thus ignored those most in need of reform.138

The passing of a statute and its demands actually being put into practice were still two rather different matters, however. In 1841, the governor of the St Alban’s county gaol was found still to be charging sick inmates for ‘extras’ prescribed by the prison surgeon – meat and vegetables at 8d per plate, beer at 4d per quart and tea or broth at 3d per basin. The governor professed complete ignorance of the 1823 Act, claiming that he had never been made aware of its contents.139

In 1842, London’s three debtors’ prisons, the Fleet, the Marshalsea and the Queen’s (formerly King’s) Bench, which were all excluded from the 1823 Act, were ‘consolidated’. The former two were wound down and closed with their prisoners transferring to what became known as the Queen’s prison and which then operated in line with the Act.

Further moves towards more standardised operation came in the wake of the 1835 Prisons Act which set up the Inspectors of Prisons. In 1843, under the direction of Home Secretary, Sir James Graham, the inspectors examined the whole system of prison ‘discipline’, including such matters as the employment, diet and health of prisoners, arrangements for their religious instruction and moral improvement, the use of punishments such as the tread-wheel, and the temperature of the cells. As a result of their investigations, a set of regulations was devised to try and bring some consistency to the operation of the 220 or so prisons then operating in England and Wales.

Despite the problems experienced at Pentonville, it marked the start of a boom in prison construction. In the six years following its building, fifty-four new prisons were erected, providing 11,000 separate cells. 140 Pentonville’s open gallery radial design became a model for many new local prison buildings and between 1842 and 1877 around twenty gaols or houses of correction were erected on similar lines. 141 These included new county prisons at Reading, Clerkenwell, Wakefield, Aylesbury, Winchester, Exeter, Wandsworth, Lewes, Warwick, Coldbath Fields (Middlesex), Salford and Lincoln, together with borough prisons at Leeds, Birmingham, Manchester, Liverpool, Hull and Portsmouth. Most were located on green-field sites at the edge of town, although some, such as Reading and Clerkenwell, reconstructed existing buildings. The new City of London House of Correction, opened in 1852, was located to the north of London at Holloway since no suitable site could be found within the city itself.

Even at prisons where wholesale rebuilding was not possible, such as those occupying castles or confined town sites, there was a move to adopt Pentonville’s principles by converting buildings to provide separate cells, or by constructing new separate-cell blocks, as happened at prisons such as Stafford, Gloucester, Oxford, Bodmin, Maidstone and Newgate.

Despite the adoption of the separate system at Pentonville, some local prisons such as Wakefield, Derby and Coldbath Fields opted to use the silent system. Journalist Henry Mayhew, visiting Coldbath Fields in the late 1850s, reported that the system required a higher proportion of officers to supervise the prisoners than at Pentonville, and that the relative number of punishments inflicted was also higher. Mayhew was particularly critical of the ‘stark waste of intellect’ resulting from the silent system, where the prisoners could not even be read aloud to during the enforced ‘utter mental idleness’. Despite the strict regime, the Coldbath Fields governor admitted that some prisoners did manage to communicate using ‘significant signs’. 142 Touching one’s nose to indicate a wish for tobacco may be the origin of ‘snout’ – a slang word for the substance, particularly associated with prisons.

PUBLIC WORKS PRISONS

By the 1840s, the decline in the number of available destinations for transporting convicts led to the development of alternative forms of sentence at home. In 1848, a ‘public works’ prison housing 840 prisoners was opened at Portland in Dorset where the inmates were employed in the local quarries and naval dockyard. A similar but much larger establishment was constructed at Portsmouth in 1852. On Dartmoor, part of the old prisoner-of-war prison – largely empty since 1815 – was put to use as a public-works project, with over 1,000 prisoners working on the land, renovating the building and adapting it to house invalid prisoners.

From 1848, convicts sentenced to between seven and ten years transportation could instead receive twelve months of separate confinement at Pentonville (or Millbank for women), followed by up to three years hard labour at Portland, Dartmoor or on the hulks, with good conduct earning a shorter stay. They would then be transported to Van Diemen’s Land or Western Australia, there receiving a pardon so long as they did not return to Britain.

Van Diemen’s Land closed its doors to convicts in 1852, leaving just Western Australia available for transportation, and then only of men. The following year, the Penal Servitude Act replaced transportation sentences of less than fourteen years by a shorter sentence of imprisonment in England. This again comprised an initial period of separate confinement, now reduced to nine months, at Pentonville, Millbank or the new women’s convict prison at Brixton opened in 1853. This was followed by a period of labour on public works, then release on licence – the beginnings of the parole system. This was a development which aroused some concern amongst the public.

The general use of transportation ceased in 1857, replaced in all cases by sentences of penal servitude. The same year also saw the demise of the last remaining hulks. To cope with the increasing numbers now needing prison accommodation, a further public-works prison was opened on St Mary’s Island at Chatham.

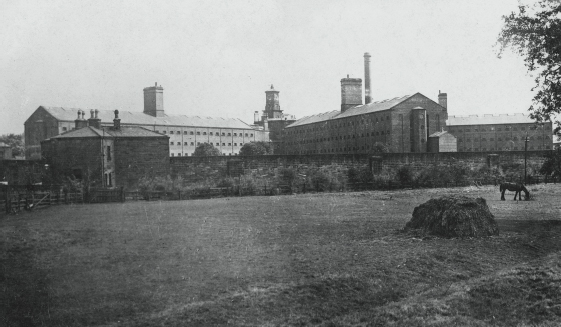

A view of the West Riding County Gaol at Wakefield, erected in 1843–7, and one of the many prison designs of the period influenced by Pentonville’s radial layout.

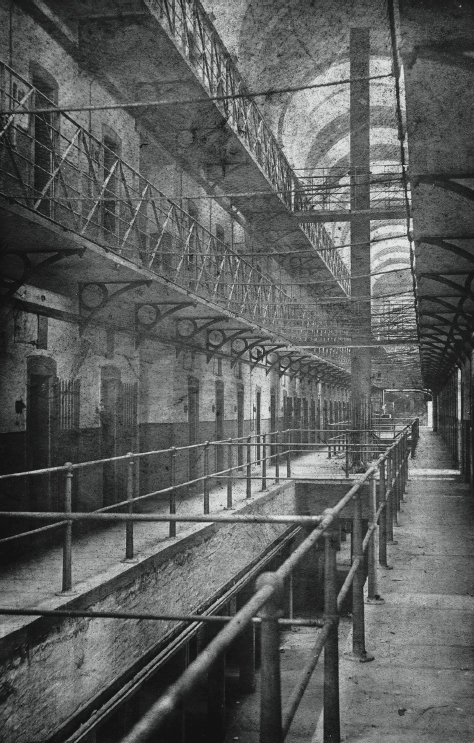

The galleried interior of one of Wakefield’s cell wings.

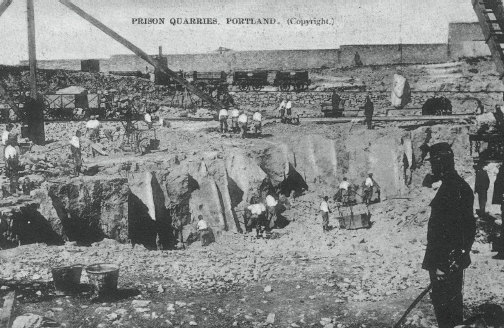

From 1848, up to a thousand convicts extracted and dressed stone at the public-works quarries at Portland. Between 1849 and 1872, 6 million tons of the stone were used to create a breakwater for Portland harbour.

YOUNG OFFENDERS

Prior to the 1850s, children who broke the law were subject to exactly the same penalties as adults, including execution, transportation and flogging. Some typical examples of Old Bailey sentencing were proffered by a schoolmaster who had spent eight months in Newgate. One boy, aged no more than 13 and not a known offender, was to be transported for life for stealing his companion’s hat while at a puppet show. The unfortunate child said that he had knocked the hat off in fun, and that someone else must have picked it up. Other boys of a similar age were sentenced to death for petty offences:

I have had five in one session in this awful situation; one for stealing a comb almost valueless, two for a child’s sixpenny story-book, another for a man’s stock, and the fifth for pawning his mother’s shawl. 143

An early attempt to deal with young offenders came in 1838 when a former military hospital at Parkhurst on the Isle of Wight was converted for use as a juvenile penitentiary. It aimed to provide under-18s who had been sentenced to transportation with a preparatory period of discipline, education and training in a useful trade. Each boy’s progress at Parkhurst would determine whether he would be transported as a free emigrant, with a conditional pardon or to be detained on arrival. The Parkhurst regime was extremely strict and included a prison uniform, leg irons, silence on all occasions of instruction and duty, constant surveillance by officers and ‘a diet reduced to its minimum’.144 The original dietary, with breakfasts and suppers largely consisting of oatmeal, led to numerous health problems such as skin eruptions. A revised dietary, issued in 1843, included bread and cocoa for breakfast, bread and gruel for supper, and dinners of bread and potatoes accompanied by either mutton or beef and vegetable soup.145 The conduct of Parkhurst boys after arrival in Australia did not live up to expectations and in 1863 Parkhurst was turned over for use as a women’s convict prison.

A completely new approach to the treatment of young offenders came in the Reformatory School Act of 1854, which enabled courts to place under-16s for a period of two to five years in reformatory schools that had been certified by the Inspectors of Prisons.

The 1857 Industrial Schools Act provided for children aged 7 to 15 and convicted of vagrancy to be placed in a broadly similar type of establishment known as an industrial school. From 1861, unruly children from workhouses or pauper schools could also be sent to industrial schools, so long as they had not been previously convicted of a felony.

Most reformatories and industrial schools were privately run, often by religious groups, although a few, such as the Feltham Industrial School, were operated by public authorities. Boys at Feltham were taught trades such as carpentry, bricklaying, tailoring and shoemaking – all the boys’ clothes and boots were made at the school.146 They also worked on the school’s own farm which was cultivated entirely by manual labour. The school was run very much along military lines and had a rigged ship fitted out for performing drill and naval exercises.

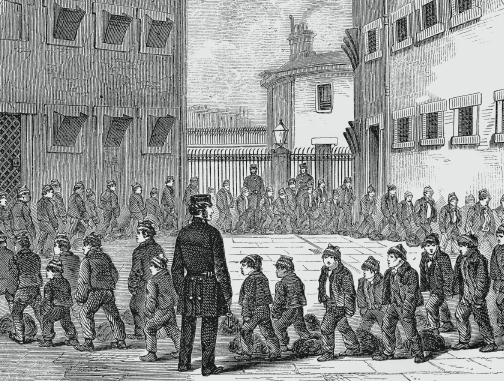

Tothill Fields prison, the Middlesex House of Correction for women and juveniles in the late 1850s. Henry Mayhew, observing the boys exercising, could ‘tell by their shuffling noise and limping gate, how little used many of them had been to such a luxury as shoe leather’. The majority of the boys were imprisoned for pickpocketing or other petty thieving.

The schools were not always successful and some closed within a few years. A reformatory opened in 1856 by the monks of St Bernard’s Abbey at Whitwick in Leicestershire took up to 250 delinquent Roman Catholic boys and was run with the help of lay assistants. However, the staff were unable to control their charges. There were several riots, and in 1878 sixty boys escaped after attacking the master in charge with knives stolen from the dining room. The establishment closed in 1881 after its certification was withdrawn.

A general view of Parkhurst juvenile prison in 1847 with some of the longer established inmates engaged in ‘spade husbandry’. For their first few months, new arrivals spent nineteen hours a day alone in cells measuring 11ft by 7ft, leaving only for exercise, cleaning, chapel and school. Misbehaviour could result in a spell inside a ‘dark cell’.

The Middlesex Industrial School was established in 1854 by a private Act of Parliament and was the first institution of its type. Its new premises, erected on a 100-acre site at Feltham in Middlesex, could hold up to 700 boys aged seven to thirteen.