eleven

Towards a National Prison System 1863 – 1878

For many convicts during the 1850s, the hardships of penal servitude became less severe. The initial period of confinement at Pentonville came down to nine months and the wearing of masks by prisoners outside their cells was dropped. The compartmentalised chapel seats became open benches, and segregated exercise yards were replaced by circular tracks. Such relaxations did not, however, meet with universal approval. Much of the criticism was aimed at Joshua Jebb who, in 1850, had become chairman of the Directors of Convict Prisons. An opportunity for Jebb’s critics came early in 1863 after London had been subjected to an outbreak of ‘garrotting’ or violent mugging, which many people blamed on convicts let out of prison under licence. In February 1863, a House of Lords Select Committee was set up under Lord Carnarvon to examine ‘the present state of discipline in gaols and houses of correction’.

HARD LABOUR, HARD FARE AND A HARD BED

The Carnarvon Committee’s report noted the ‘many and wide differences, as regards construction, labour, diet and general discipline’ in the country’s prisons, which resulted in an ‘inequality, uncertainty and inefficiency of punishment’.167 To rectify this situation, the committee recommended that all prisons should adopt the separate system of confinement. The primary aims of the prison, it believed, were punishment and deterrence, achieved through a regime characterised by ‘hard labour, hard fare, and a hard bed’. The interpretation of ‘hard labour’, it was observed, varied widely and the report proposed that it should be precisely defined using measurable tasks. As well as the tread-wheel, these included shot drill (where a heavy metal ball was raised and lowered in various sequences) and crank turning (where a handle whose stiffness could be adjusted was turned a specified number of times). Prison diets were viewed by the committee as forming part of an inmate’s punishment and should be set accordingly. There should be no incentive for workhouse inmates, for example, to commit crimes in order to enjoy a better standard of food in prison. As regards a ‘hard bed’, the Carnarvon Report recommended that prisoners should spend at least part of their sentence sleeping on planks, with no more than eight hours spent in bed per night. Despite the more severe conditions favoured by the report, it also proposed a system of ‘marks’ where a prisoner’s good conduct and hard work could be rewarded by promotion to a grade demanding less labour and better food.

The Carnarvon Committee’s recommendations resulted in the 1865 Prisons Act,168 which made adoption of the separate system compulsory in all local prisons. It defined two classes of hard labour. The first required male convicts during the first three months of their sentence to work for up to ten hours a day at the tread-wheel, shot drill, crank, capstan or stone-breaking. The second, less onerous, class of labour was left for local Justices to approve. Exercise, diet and the use of plank beds were also left to local discretion, but all dietaries had to be submitted for central approval. To create consistency of operation, the 1865 Act included a list of 104 regulations for the running of prisons. Finally, the long-standing legal distinction between local gaols and houses of correction was abolished. It was decreed that any prison that was unwilling or unable to adopt the requirements of the Act would have to close or amalgamate with a neighbouring institution. This was a course taken by a number of prisons, especially smaller establishments or those with old buildings where the cost of meeting the new regulations proved prohibitive. Of the 187 prisons operating in 1850, only 126 remained open in 1867.169

In parallel with the Carnarvon Committee, a Royal Commission, chaired by Earl Grey, reviewed sentencing policies. The resulting 1864 Penal Servitude Act specified that five years should be the minimum length of a sentence of penal servitude, or seven years for re-offenders. Responding to concerns over the garrotting outbreak, it also introduced stricter supervision of convicts released under licence. The changes necessitated a gradual increase in the provision of public-works prisons, with new ones opening at Borstal in 1874 and Chattenden in 1877.

THE 1864 DIETARIES REPORT

After hearing lengthy – and sometimes contradictory – scientific evidence from Edward Smith and William Guy on matters such as the relationship between adequacy of diet and resulting changes in body weight, the Carnarvon Committee had felt unable to propose a specific new dietary. Instead, a three-man committee of prison medical officers, chaired by William Guy, was set up to examine Sir James Graham’s 1843 dietaries and devise new ones for use in local prisons.

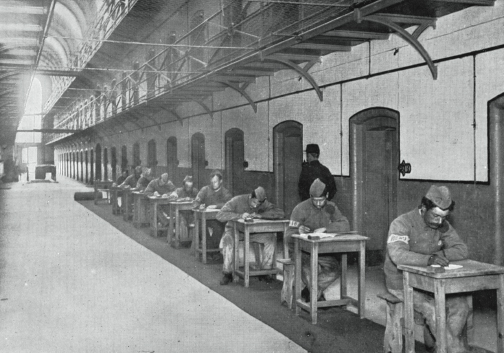

A prisoner doing a shift of crank-turning at the Surrey House of Correction, Wandsworth, in around 1860.

In their report, published in May 1864, the committee concluded that the existing dietaries were ‘strangely anomalous and eminently unsatisfactory’ – for example, the amounts of bread and potatoes given to female prisoners appeared to bear no consistent relationship to the corresponding allowances received by male inmates.170 The committee also noted the very wide range of tasks that were provided as ‘hard labour’. This had led to significant inequalities in the discrepancies in the dietaries allocated to inmates at different prisons, with some establishments even giving the same dietary to those serving sentences with or without hard labour. The report side-stepped the disagreements between William Guy and Edward Smith on what constituted a sufficient diet by deciding that the available scientific evidence was of ‘ limited and uncertain practical value’. At the end of the day, it was ‘experience’ and ‘prevailing opinions’ that guided the committee’s conclusions. 171

The committee recommended that the diet provided for prisoners should be related to the labour that they actually performed. The basic dietary would therefore provide for those not undertaking hard labour, with various additions allowed where labour was imposed. As before, the report proposed a graded series of dietaries for different lengths of sentence, with prisoners on longer terms eventually being allowed items such as meat and cheese. However, based on advice from various prison authorities, it was now recommended that prisoners sentenced to longer terms of imprisonment should progressively pass through the diets of all the sentences shorter than their own. Women were, as standard, to receive three quarters of the rations provided to male prisoners. The new dietary scheme is summarised in the table below:

1864 Dietaries for County and Borough Gaols for Prisoners without Hard Labour |

|||||||||||

Meals |

Articles of Food |

Class 1 |

Class 2 |

Class 3 |

Class 4 |

Class 5 |

|||||

One week or less. |

After 1 week, to 1st month inclusive. |

After 1 month, to 3rd month inclusive. |

After 3 months, to 6th month inclusive. |

After 6 months |

|||||||

M |

F |

M |

F |

M |

F |

M |

F |

M |

F |

||

oz |

oz |

oz |

oz |

oz |

oz |

oz |

oz |

oz |

oz |

||

Breakfast |

Bread |

6 |

5 |

6 |

5 |

8 |

6 |

8 |

6 |

8 |

6 |

Gruel |

- |

- |

1pt |

1pt |

1pt |

1pt |

*1pt |

*1pt |

*1pt |

*1pt |

|

Supper |

Bread |

6 |

5 |

6 |

5 |

6 |

6 |

8 |

6 |

8 |

6 |

Gruel |

- |

- |

- |

- |

1pt |

1pt |

1pt |

1pt |

*1pt |

*1pt |

|

Dinner |

Bread |

8 |

6 |

8 |

6 |

10 |

8 |

10 |

8 |

12 |

10 |

Cheese |

- |

- |

1 |

1 |

2 |

2 |

3 |

2 |

3 |

2 |

|

Mon, |

Bread |

6 |

5 |

6 |

5 |

4 |

4 |

4 |

4 |

4 |

4 |

Potatoes |

- |

- |

- |

- |

12 |

8 |

16 |

12 |

16 |

12 |

|

Suet Pudding |

- |

- |

- |

- |

8 |

6 |

12 |

8 |

12 |

8 |

|

Indian Meal Pudding |

6 |

4 |

8 |

6 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

Tue, |

Bread |

6 |

5 |

6 |

5 |

8 |

6 |

8 |

6 |

8 |

8 |

Potatoes |

8 |

6 |

12 |

8 |

8 |

6 |

8 |

6 |

16 |

12 |

|

Soup |

- |

- |

- |

- |

¾pt |

¾pt |

1pt |

1pt |

1pt |

1pt |

|

* To contain 1oz of molasses on Sundays. |

|||||||||||

Prisoners awaiting trial and destitute debtors were to be given the Class 3 diet for their first month, the Class 4 for their second month, then the Class 5 for any further time of imprisonment. Debtors and bankrupts committed for fraud or other serious offence, and also deserters, were placed on the Class 3 diet for the duration of their stay.

A new dish on the menu was Indian meal pudding. Indian meal (milled maize corn, or cornmeal) was not a traditional foodstuff in England though supplies from North America were sometimes used as pig-feed. It was, however, eaten by the poor in many countries, for example in Italy as the dish polenta. Supplies had also been shipped to Ireland to feed the starving poor during the famine between 1845 and 1850. For those in Classes 3–5, Indian meal pudding was replaced after a month by suet pudding, an item which had occasionally featured on prison menus since at least 1818 when it was part of the dietary at the Maidstone House of Correction. It was now commended as ‘easily made and measured’ and ‘palatable without being luxurious’.172

At first glance, the basic dietary appears to lack any meat. However, the ingredients list that accompanied it includes some in the soup served for dinner three times a week:

Ingredients of Suet Pudding |

Ingredients of Indian Meal Pudding |

Ingredients of Gruel |

As with the 1843 dietary proposals, the new scheme was presented only as a recommendation for local prisons to follow, should they decide to do so in consultation with local magistrates.

At the same time as local prison dietaries were being reviewed, another committee was reassessing those in use at the convict prisons. For male convicts in separate confinement, the following dietary was proposed for those engaged in ‘industrial employment’:

BREAKFAST (All days) |

Bread. ¾ pint cocoa (containing ½oz cocoa, 2oz milk, ½oz molasses). |

DINNER Sunday |

Bread. 4oz cheese. |

Monday |

Bread. 1lb potatoes. 4oz hot mutton (with its own liquor, flavoured with ½oz onions, and thickened with bread left on previous day). |

Tuesday |

Bread. 1lb potatoes. 4oz hot beef. |

Wednesday |

Same as Monday. |

Thursday |

Bread. 1lb potatoes. 1lb suet pudding (containing 1½oz suet, 8oz flour, 6½oz water). |

Friday |

Same as Tuesday. |

Saturday |

Bread.1lb potatoes.1 pint soup (containing 8oz shins of beef, 1oz pearl barley, 3oz fresh vegetables including onions). |

SUPPER (All days) |

Bread. 1 pint gruel (containing 2oz oatmeal, 2oz milk, ½oz molasses). |

Bread, per week: 148oz (20oz per weekday, 28oz Sunday) |

|

Males not at industrial employment received the same dietary but with the bread allowance reduced by 4oz a day. Women convicts had a single ‘ordinary’ dietary – a slightly reduced version of the men’s rations – with those engaged in washing or other heavy work receiving the men’s meat allowance plus a lunch of bread and cheese between breakfast and dinner. Finally, for anyone breaking prison rules, a punishment dietary consisted of bread (1lb per day) and water. For punishments above three days, a ‘penal class’ diet of bread, porridge and potatoes was served every fourth day. Cocoa, which the committee reviewing local prison dietaries had decided was an unnecessary luxury, was retained at convict prisons.

NATIONALISATION

Although the 1865 Prison Act brought local prisons under some degree of central control, they were still funded by local rates, with local JPs playing a part in their administration. The final step in creating an integrated national prison system came with the 1877 Prison Act which placed control of all prisons in the hands of a new body known as the Prison Commissioners. At the same time, the Exchequer took over all the costs of running the prison system.

The nationalisation of the prisons aimed to make the operation of the penal system both uniform and economical. To this end, the Commissioners, chaired by Sir Edmund Du Cane, set about rationalising the country’s stock of 113 prisons. In the summer of 1878, forty-five were shut down – mostly small town gaols, although eleven county prisons were closed. The remainder provided space for 24,812 inmates – about 4,000 more than the expected requirements. 173

Unlike its predecessor in 1865, the new Act did not include detailed prison regulations. Instead, a new set of rules devised by the Prison Commissioners was introduced in April 1878. One innovation was a system of four stages through which convicted prisoners could progress during their sentence. In Stage 1, prisoners slept on a plank bed with no mattress. They were employed for ten hours a day in First Class hard labour, of which six to eight hours were to be on a crank- or tread-wheel. No money could be earned. In Stage 2, a mattress was provided for the plank bed on five nights a week. After completing a month of First Class hard labour, Stage 2 prisoners were moved to Second Class hard labour – light industrial work, for which a small payment could be earned. Stage 2 also offered inmates school instruction and a period of exercise on Sunday. Stage 3 reduced the bare plank bed to one night a week, allowed library books to be kept in cells and gave a higher rate of earning. Finally, at Stage 4, prisoners had a mattress every night and a further increase in earnings. More significantly, they could be given jobs of trust within the prison, have a visitor every three months and write and receive a letter.

Progress through the stages was achieved by the accumulation of marks, of which six to eight could be earned each day. Attaining a total of 224 marks (i.e. twenty-eight times eight) in a stage earned advancement to the following one, although idleness or misconduct could be punished by loss of earnings, stage privileges or even temporary demotion to an earlier stage.

Second Class labour covered a variety of tasks and could result in the learning of a trade that would make an inmate employable after release. At Manchester in 1886, the work for men included brush making and calico weaving, while women were occupied at knitting, sewing, cotton picking and making mail bags. 174 At Wakefield, the men’s employment included mat-making, stocking weaving and hammock making. Many of the goods produced by prisoners were supplied to government departments such as the War Office, Admiralty and Post Office.

THE NATIONAL PRISON DIETARY

Following the creation of a national prison system in 1877, a review of prison diets was undertaken with the aim of finally establishing a scheme that could be used by all the country’s prisons. A committee was set up to consider the matter and made its report in February 1878.

In its report, the committee noted that the dietaries in use at local prisons were now more varied than ever, with eighty-one differing widely from current official recommendations, compared to eighteen in 1864. 175 Many prisons were still using dietaries similar to those issued following the 1843 review. The committee endorsed the existing view that those serving short terms should receive a more severe diet than those on longer sentences. It also broadly agreed with the principle that longer-term inmates should progress through the various diets given to those with shorter sentences. However, it recognised that the number of potential dietary combinations of male and female prisoners, with and without labour, and at different stages of their sentence, could be excessive – with some prison kitchens having to deal with up to eighteen different diets on the same day. To address this, the committee proposed that the number of basic dietary classes be reduced to four. It was also recommended that female prisoners should generally receive the same amounts as males not performing hard labour. For longer-term prisoners, a revised system of progression was devised, with each prisoner receiving just the last two dietaries applicable to their length of sentence. The revised scheme is shown below:

|

Dietary |

|||

Sentence Length |

Class 1 |

Class 2 |

Class 3 |

Class 4 |

Up to 7 days |

Whole term |

|

|

|

From 7 days to 1 month |

First 7 days |

Remainder |

|

|

From 1 month to 4 months |

|

First month |

Remainder |

|

More than 4 months |

|

|

First 4 months |

Remainder |

From 1878, Stage 4 prisoners could periodically send and receive a letter. A group of inmates engrossed in their writing are seen here at Wandsworth prison in 1896.

By the end of the nineteenth century, unproductive labour such as the tread-wheel had been replaced by more useful occupations which could result in a prisoner learning a trade. This 1898 scene shows the mechanical shop at Wormwood Scrubs where small metal containers are being made under the careful watch of prison officers.

Prisoners at Portland were not solely occupied in the quarries, as shown by this view of the fitter’s shop.

The governor and staff at Shepton Mallet prison in Somerset, early 1900s. In 1878, a national scale was created for prison staff ’s pay. Governors of prisons with 1,000 inmates or more started at £710 a year, with free accommodation and medical care. At a smaller prison like Shepton Mallet, the governor received a rather more modest £200. A warder’s salary was £70, plus uniform and accommodation.

In terms of the food provided in each class, the committee was decidedly of the view that ‘the shorter the term of imprisonment, the more strongly should the penal element be manifested’; that ‘a spare diet is all that is necessary for a prisoner undergoing a sentence of a few days or weeks’; and that ‘to give such a prisoner a diet necessary for the maintenance of health during the longer terms would be to forgo an opportunity for the infliction of salutary punishment’.176 For longer terms, however, it was accepted that a more substantial and varied diet was appropriate. The details of the new dietary recommendations are shown below:

|

CLASS 1 |

CLASS 2 |

|||||

Meals |

|

Men, Women, and Boys under 16, with or without Hard Labour. |

|

Men with |

Men not on Hard Labour, Women, Boys under 16. |

||

Breakfast |

Daily |

Bread |

8oz |

Daily |

Bread |

6oz |

5oz |

Gruel |

1 pint |

1 pint |

|||||

Dinner |

Daily |

Stirabout |

1½ pints |

Sun, |

Bread |

6oz |

5oz |

Suet Pud. |

8oz |

6oz |

|||||

Mon, |

Bread |

6oz |

5oz |

||||

Potatoes |

8oz |

8oz |

|||||

Tue, |

Bread |

6oz |

5oz |

||||

Soup |

½ pint |

½ pint |

|||||

Supper |

Daily |

Bread |

8oz |

Daily |

Bread |

6oz |

5oz |

Gruel |

1 pint |

1 pint |

|||||

|

CLASS 3 |

CLASS 4 |

|||||||

Meals |

|

Men |

Men not on Hard Labour, Women, Boys |

Destitute Debtors, Prisoners awaiting trial, etc. |

|

Men |

Men not on Hard Labour, Women, Boys |

||

Breakfast |

Daily |

Bread |

8oz |

6oz |

6oz |

Daily |

Bread |

8oz |

6oz |

Gruel |

1 pint |

1 pint |

1 pint; or |

Porridge |

1 pint |

|

|||

Cocoa |

|

|

½ pint |

Gruel |

|

1 pint |

|||

Dinner |

Sun, |

Bread |

4oz |

4oz |

4oz |

Sun, |

Bread |

6oz |

4oz |

Potatoes |

8oz |

6oz |

6oz |

Potatoes |

8oz |

8oz |

|||

Suet |

8oz |

6oz |

6oz |

Suet |

12oz |

10oz |

|||

Mon, |

Bread |

8oz |

6oz |

6oz |

Mon, |

Bread |

8oz |

6oz |

|

Potatoes |

8oz |

8oz |

8oz |

Potatoes |

12oz |

10oz |

|||

Ckd. |

3oz |

3oz |

3oz |

Ckd. |

4oz |

3oz |

|||

Tue, |

Bread |

8oz |

6oz |

6oz |

Tue, |

Bread |

8oz |

6oz |

|

Potatoes |

8oz |

6oz |

6oz |

Potatoes |

8oz |

8oz |

|||

Soup |

¾ pint |

¾ pint |

¾ pint |

Soup |

1 pint |

1 pint |

|||

Supper |

Daily |

Bread |

6oz |

6oz |

6oz |

Daily |

Bread |

8oz |

6oz |

Gruel |

1 pint |

1 pint |

1 pint; or |

Porridge |

1 pint |

|

|||

Cocoa |

|

|

½ pint |

Gruel |

|

1 pint |

|||

Economy, as always, was kept in mind and the authors of the 1878 report were keen to extol the virtues of pulses – peas and beans. For Class 3 and 4 inmates, replacing Monday’s cooked beef by ‘beans and bacon’ (9oz haricot beans, 1oz fat bacon, 12oz potatoes, 8oz bread) would, it was claimed, be more nutritious and also reduce the cost from 4¾d to 2¼d a portion.

A notable absence from the new dietary was Indian meal pudding, introduced for Class 1 and 2 prisoners in the 1864 review. Indian meal continued in use, for Class 1 prisoners, in the guise of ‘stirabout’, a thick porridge containing equal parts of Indian meal and oatmeal. Despite appearances, ‘stir’ – one of the English slang terms for prison – is not a shortened form of stirabout, but is said to derive from the Romany word ‘sturiben’, meaning ‘to confine’.177

The new diets were endorsed by an 1878 Royal Commission who found that the quantities were ‘fairly proportioned to the amount of labour required of the prisoners, whether in separate confinement or at public works’. The meals themselves also received a seal of approval: ‘though they are coarse in quality, they are good and of their kind nutritious, and sufficient in quantity to maintain ordinary convicts in good health and vigour.’178 This was not a view that everyone felt inclined to agree with.

Located in the town’s market place, Buckingham’s borough prison was erected in 1748 in the style of a castle, the traditional setting for a prison. By the 1870s, its inmates rarely numbered more than three and it became one of many small local prisons to close following the nationalisation of the prison system in 1877. The building, now a museum, has also served as a police station, fire station, ammunition store, public conveniences and an antiques shop.